Monday May 31, 2010

Review: “Restrepo” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Restrepo” is the best thing I’ve seen or read about our presence in Afghanistan, and it’s not really about our presence in Afghanistan. It’s about, as the tagline says, one platoon, in one valley, for one year. It goes deep into these soldiers’ lives without telling us much about their actual lives (where they’re from, why they signed up, etc.). It’s an emotional movie precisely because its emotions are restrained. It’s artistic without being artistic. It’s artistic in the Dedalean sense. It doesn’t inspire kinetic emotions but static emotions. The mind is arrested. In this sense maybe Afghanistan itself is artistic. Our mind has been arrested there for almost 10 years.

The directors, author Sebastian Junger (“The Perfect Storm”; “War”) and documentarian Timothy Hetherington (“Liberia: An Uncivil War”), were embedded with Second Platoon, Battle Company, 173rd US Airborne, for parts of a year, from May 2007 to July 2008, and an early scene lets us know just how embedded they were. We’re inside a HUMVEE on patrol when an IED goes off, rocking the vehicle. The men stumble out, including the camera, which is our point-of-view. It’s still filming, shakily, while the men engage in a firefight, but it’s crackling, and there’s no sound. You think of war scenes where a soldier gets shelled and the sound goes out because he’s deafened or in shock. Same here. Our equipment is us.

What Restrepo means

We first see the men of Second Platoon goofing around and trash talking aboard a train before deployment. Then they ride Chinook helicopters into the dangerous Korengal valley, a beautifully mountainous but militarily indefensible region that stretches six miles along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and the trash talking stops. In post-deployment interviews, they fess up to their initial thoughts. Specialist Sterling Jones: “What are we doing?” Sgt. Aron Hijar: “We are not ready for this.” Specialist Miguel Cortez: “I’m going to die here.”

We first see the men of Second Platoon goofing around and trash talking aboard a train before deployment. Then they ride Chinook helicopters into the dangerous Korengal valley, a beautifully mountainous but militarily indefensible region that stretches six miles along the Afghanistan-Pakistan border, and the trash talking stops. In post-deployment interviews, they fess up to their initial thoughts. Specialist Sterling Jones: “What are we doing?” Sgt. Aron Hijar: “We are not ready for this.” Specialist Miguel Cortez: “I’m going to die here.”

Sgt. Joshua McDonough tells the camera, “They’re gathering intel on how to deal with us,” and you think he’s talking about the Taliban, who are trying to kill them, but he’s actually talking about the post-deployment medical personnel in Italy, who are trying to help them. This confusion, this thin line, is what the soldiers deal with every day. Who among the villagers is trying to help? Who is trying to hurt? How do you tell?

The doc keeps doing this. The thing you think we’re talking about isn’t the thing we’re talking about. Information is slowly widened. Clarity, if it comes, comes by and by.

Take the title. “Restrepo”? What the hell's that? Then on that pre-deployment train we discover that the biggest trash talker with the biggest smile is a guy named Juan S. “Doc” Restrepo. “Oh,” we think. “So Restrepo’s a guy. This is a documentary about a guy.” A few minutes later, we find out Restrepo was killed a month into deployment. “Oh,” we think. “So this is a doc about how these guys deal with the loss of this guy.” Then the company moves deeper into the Korengal valley, establish an outpost there, and name it Restrepo, O.P. Restrepo, in honor of their fallen friend. “Oh,” we think. “So this is... Well, this is about all of it, isn’t it?” Our information is slowly widened. Clarity comes by and by.

O.P. Restrepo is deeper into the Korengal Valley than the U.S. has ever pushed before, and four or five times a day, for weeks and months, Second Platoon engages in firefights with the unseen Taliban in the woods. “They’d ambush us from 360 degrees,” Specialist Bemble Pelkin says. “I felt like a fish in a barrel,” Capt. Dan Kearney says. When there are no firefights, there’s digging and fortifying the outpost; and when there’s no digging and fortifying, there’s goofing around to relieve the boredom. Pemble draws and writes. Specialist Angel Toves plays guitar. The men wrestle, or get newbies to wrestle, or goof around with the ‘80s song “Touch Me (I Want to Feel Your Body).” They show off photos of their kids. They hit golf balls into the valley.

The incident with the cow starts out as a joke. A daily briefing, a smile, “we’ll talk about the cow incident later,” laughter from the men. It’s a funny thing. Later, a soldier talks up the day they got fresh cow to eat, saying, “That was a good day.” Later still, three Afghani village elders, with their long beards and taut skin over high cheekbones. enter O.P. Restropo, and it’s seen as a positive step. Hearts and minds are being won. But the elders have come about the cow. It was one of theirs and they want to be repaid. Now it’s a serious thing. The soldiers are apologetic—it got caught in the wire, it had to be killed (then eaten)—but the elders want US$400, which the U.S. higher-ups refuse to give. We’re spending billions on wars but we can’t get US$400 to replace a cow. Instead the owner gets the equivalent in rations: rice and beans. The elders leave. Are we being too tough? Not tough enough? Our information is widened but not enough. Clarity doesn’t come.

This hearts and minds struggle is fascinating to watch. We see Capt. Kearney, with the best of intentions, having regular sitdowns, or shura, with the village elders, but there’s something Business 101 about him. Support us, he tells the elders, and we’ll “make you guys richer.” What about the killing of civilians? the elders want to know. The Captain says it’s all in the past, on another captain’s watch, and insists that everyone needs to put the past behind them. Does this translate? In a later meeting, frustrated beyond measure, he says to the elders, “You are not understanding that I don’t fucking care.” Is this translated? With all of the specialists we have, one wonders why we have no diplomatic specialists. Why aren’t diplomats embedded with soldiers? Why don’t our head honchos speak rudiments of the language? Why, in the soldiers’ down time, don’t they learn rudiments of the language? Why aren’t we adapting?

Three faces

“Restrepo” is never not fascinating, which is odd, because we know answers to most of the questions that traditionally drive storytelling. We know who survives (anyone interviewed post-deployment), and we know O.P. Restrepo won’t be the turning point of the war (we’re in 2010 and we read the newspaper), so what keeps us glued to our seats? I think the short answer is we begin to care. And we want to know what happens to these people we begin to care about.

Why do we begin to care? John Ford once said the most interesting thing in the world to film is the human face, and that’s what Hetherington and Junger keep filming. Three faces stand out.

First, there’s Pemble, who’s got a calm, bemused way about him, like he’s holding onto an inner joke, and who’s a warning to every parent who thinks restricted access will diminish lifelong interest. His mom, he tells us, “was a fucking hippy” (he says it nicely) who didn’t allow him toy guns, or violent movies, or violent video games. And yet here he is—a soldier in Afghanistan. To mom’s credit, he seems the least likely of soldiers. There’s little that’s gung ho about him. He feels like he should be in a punk bar somewhere.

Then there’s Hijar, who’s got huge, tattooed arms in the footage, and an intense, haunted face in the post-deployment interviews. He and the others are talking about Operation Rock Avalanche, a three-day tactical walk-though in a Taliban stronghold, which all agree was the toughest part of the deployment. During the operation, Staff Sergeant Kevin Rice was injured and Staff Sergeant Larry Rougle, generally considered the platoon’s best soldier, was killed, and trying to describe it all, Hijar disconnects. His eyes get lost and he stops talking, and after 10 seconds of silence he looks at the cameraman: “Timeout, alright?” Later he talks about needing a different way to process everything that’s happened. He doesn’t want to forget it, he says; he just needs to process it differently.

Finally, there’s Cortez, who’s smiling, always smiling in the post-deployment interviews. One wonders: “Why is this dude smiling?” Then you realize there’s a disconnect between the look on his face and what he’s saying. Near the end, he talks about how he can’t sleep.

I’ve been on four or five different types of sleeping pills and none of them help. That’s how bad the nightmares are. I prefer not to sleep, and not dream about it, than sleep and see the pictures in my head. It’s...pretty bad.

The smile never leaves his face.

“Restrepo” should get nominated for an Academy Award for best documentary feature, and, unless it’s a helluva year, it should win. It’s already got my early vote for one of the best films of the year. There’s not a false moment in it, not a dull moment in it, and in a serious country it would be released into over 4,000 theaters and everyone would see it. But we’re not a serious country. We haven’t been a serious country for decades. A Roman helmet is painted on a wall at O.P. Restrepo, because it’s cool, I suppose, to remind the men of gladiators, I suppose, but it merely reminded me of the fall of the Roman empire, of the fall of all empires, and it made me wonder where we are in that fall.

“Restrepo” won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival and played the Seattle International Film Festival in May. It will get a wider release June 25. It's re-scheduled for Seattle on July 2.

Sunday May 30, 2010

Hollywood B.O.: Ladies Second

Two years ago "Sex and the City" made $59 million during its three-day opening weekend: $26M+ and $17M+ and $12M+. This year, "Sex and the City 2" is estimated to make $46 million over its four-day opening weekend (Thurs.-Sun.): $14M, $13M, $10M., $9M. Adjust for inflation and it's even worse: $63M for three days vs. $46M for four. Take out Thursday's total for "2" and its opening weekend is about half of what "1"'s was.

Now it could be that the fashionistas are waiting until Monday to celebrate Memorial Day with the Four Horsewomen of the Apocalypse. But I doubt it. So why the comedown?

Last week I argued the latest "Shrek" faltered because the previous "Shrek" stank. There's carryover.

I'd argue that the previous "SATC" wasn't that good, either. In fact, I did argue it. But I think "SATC 2" mostly suffered because, well, it just looked awful.

I saw a clip a few weeks ago on "The Daily Show." The four women are out in the desert riding camels. Samantha complains of hot flashes, to which Carrie states the obvious: You're in the desert; you're supposed to have hot flashes. That's a joke. Then Charlotte gets a call on her cell but she's having trouble with the connection and does the "Can you hear me now?" bit. She keeps leaning and leaning. And then she falls off the camel. That's a joke, too. And that was the clip.

And I thought: "If that's the clip, what's the rest of the movie like?"

I'm probably not the only one to have this thought.

Women, I've heard, tend to pay more attention to movie critics than men. That's one of the problems Hollywood execs have with women: they care about quality.

"SATC," of course, is a fairly critic-proof franchise but not completely. It can squeak by with a not-horrible 53% rating, as the first movie garnered from top critics at RT.com. But "SATC 2" garnered a 9% rating from top critics—and it was a pretty loud 9% rating, too. People heard. Women heard.

My guess is that "2" won't gross more than $115M. If word-of-mouth is bad, as it seems to be, it might not break its $100-million budget.

In other news, "Prince of Persia" (23%) proved it was no tentpole in the desert, finishing third with $30 million.

Their loss, "Shrek"'s gain. It fell by only 38% to remain no. 1 for the weekend. The lesser of three evils.

Friday May 28, 2010

"An Accidental Candid Snapshot of the Sick, Dying Heart of America"

There's been noise from some quarters that the negative reviews of "Sex and the City 2" are sexist, but this counterargument lands with a thud. Critics take down anything that's bad. That's what we do. We recommend what's good. That's what we do. Excusing "SATC 2" as escapist fantasy for women, while contrasting it with escapist fantasies for men such as "Taken," reveals what's truly bad about "SATC 2." (Which I haven't even seen yet, so...grain of salt.)

"Taken" is about a man who's increasingly relevant. He's necessary and important. Thus he acts as a fantasy figure for audience members who, most likely, feel increasingly unnecessary and unimportant in the world. He also answers every dramatist's first question: What does the guy want? He wants to get his daughter back. The movie is about everything he goes through to get that done.

"SATC 2" is about four women who are increasingly irrelevant. Why is this escapist fantasy? Because of the designer clothes and bags? Meanwhile, the main character, Carrie, doesn't even bother to answer the dramatist's first question. She doesn't know what she wants. She never has. With the exception of Big, whom she now has. Answered prayers.

"SATC 2" is about four women who are increasingly irrelevant. Why is this escapist fantasy? Because of the designer clothes and bags? Meanwhile, the main character, Carrie, doesn't even bother to answer the dramatist's first question. She doesn't know what she wants. She never has. With the exception of Big, whom she now has. Answered prayers.

I doubt I'll see it—SIFF's on—but here are some of the better comments I've read:

"Sex and the City 2" is more than harmless escapism. It's an accidental candid snapshot of the sick, dying heart of America, a film so pleased with its vacuous, trashy, art-free extravagance that its poster should be taped to the dingy walls of terrorist sleeper agents worldwide. More depressing and alarming than the movies themselves is the notion that a certain culture, a certain mindset, birthed it, without a pang of remorse or even apparent self-awareness, much less self-criticism. Ladies and gentlemen, this is why they hate us.

—Matt Zoller Seitz, IFC.comThe thinking behind the movie (written and directed by Michael Patrick King) is undisguised. Let’s start with an over-the-top gay wedding! Then we’ll send the girls to Abu Dhabi so they can rile up the fundamentalists with their sexuality! Then they’ll make fun of women in niqab (“Certainly cuts down on the Botox bill!”) but later show (campy) feminist solidarity! Won’t they look great swishing around the desert being waited on by smooth young Arab men?

—David Edelstein, New YorkIn one scene, Carrie asks her personal hotel butler, Guarau (Raza Jaffrey), about his family. His wife is back in India, he tells her; he flies home to see her every few months, when he can afford the fare. Carrie looks at him for a moment in silence, and we wonder: Is it possible she's confronting the unimaginable gulf that separates their two lives, the vast global network of consumption, exploitation, and injustice that's brought them together in this alien and alienating place? But no: Although she will later do Guarau a good turn, Carrie is merely wondering how she can get Big to appreciate her as much. Perched at the pinnacle of material comfort and social privilege in the waning days of the American empire, she can still find something to pout about.

—Dana Stevens, Slate.com

Thursday May 27, 2010

Talkin' (and Talkin' and Talkin') Baseball with a First-Timer from Lebanon

Two nights ago I took my friend Robert to a baseball game. His first.

Robert was born and raised in Tripoli, Lebanon, moved to the U.S. in August 2001, and doesn't know from baseball. That needed rectifying. And wasn't I the guy to do it? I had once been the SME (Subject Matter Expert) for Microsoft's “Baseball 2K,” a PC video game, and I'd taken a friend from Spain to a game several years ago and explained it to her. Promises had been made to Robert last year. Promises were finally kept two nights ago.

As Robert and I walked from our First Hill neighborhood through downtown Seattle and toward Safeco Field, I began the tutorial. There are two teams, I said: one on offense, one on defense. The team on defense is “in the field,” and at various positions around the field, to better, um, field the ball. (The editor in me shuddered.) The team on offense sends up one player at a time to home plate.

“Home plate?” Robert asked.

Yes, there are four bases.

OK, there are nine innings, and in each inning, or half inning...

OK, there are nine innings, and in each inning, or half inning...

OK, wait. A team gets three “outs,” which are, um...

Let me start over.

The team on defense has a “pitcher,” who stands 60 feet, 6 inches away from home plate. The team on offense sends a “batter” to home plate with a...um...stick.

“A bat,” Robert said.

“A bat,” Robert said.

Yes. The pitcher throws the ball toward the batter and tries to get the batter to swing and miss or hit the ball weakly. If the pitcher gets the batter to miss three times, that's an “out.” A “strikeout.” (The caveat is the foul ball, I thought, but first things first.)

There are different ways to make an out, I said. I explained the ground out, the fly out. the strikeout. Three outs and the two teams switch sides.

But the point of the game is to move the players around the bases, from first to second to third to home, and score.

“Points,” Robert said.

In baseball, I said, they‘re called “runs.” And after nine innings the team with the most runs wins. (The caveat is extra innings, I thought, but...)

We kept going. Balls and strikes. “Strike zone.” A walk. A single. Moving from base to base. I didn’t know it but I was doing a Bob Newhart routine. Was I making the game seem less bizarre to Robert? All I know is, the more I talked, and the more I explained the game at this elemental level, the more bizarre it seemed to me. Who could invent such a thing?

We kept going. Balls and strikes. “Strike zone.” A walk. A single. Moving from base to base. I didn’t know it but I was doing a Bob Newhart routine. Was I making the game seem less bizarre to Robert? All I know is, the more I talked, and the more I explained the game at this elemental level, the more bizarre it seemed to me. Who could invent such a thing?

As we entered Safeco Field, I apologized to Robert for the weather, which was overcast and drizzly. I apologized for the Mariners, who were not that good. I apologized for the sparse crowd, eventually announced as 20,920, but probably half that. Eight years ago, I said, this place would‘ve been packed.

We bought Ivar’s fish and chips and beer, and grabbed our seats: 300 level behind home plate. I explained road-gray uniforms and home-white uniforms. The players were being announced, which necessitated further explanations: line-up; batting order. “And they can't deviate from this order?” Robert asked. “And after they switch sides and return to offense, do they start at the top again?” Robert asked.

The first Major League pitcher Robert saw in person was Doug Fister, who, the scoreboard proudly displayed, was leading the league in ERA. “What's ERA?” Robert asked. The first Major League batter Robert saw in person was Austin Jackson, the Tigers' rookie center fielder, with a .333 batting average. “What's batting average?” Robert asked. These were easy ones. “Earned runs,” admittedly, was tough. It led to “unearned runs” and “errors” and “official scorers” and this question: “Does it change the outcome of the game or is it just for individual statistics?”

And in the first Major League at-bat Robert ever saw in person, Austin Jackson struck out looking.

“So what if the ball is outside the strike zone and the batter swings and misses?” Robert asked. That's a strike, too, I said. “What if the ball hits the batter?” That's a hit-by-pitch, I said, and the batter goes to first base. “So how come the batter gets out of the way?” he asked. “Doesn't he want to go to first?” Well, I said, if the umpire thinks he didn't try to get out of the way, then he might not let him go to first base. Besides, it would hurt. The ball is small and hard and thrown between 85 and 100 miles per hour. “Yes,” Robert agreed. “That would hurt.”

“So what if the ball is outside the strike zone and the batter swings and misses?” Robert asked. That's a strike, too, I said. “What if the ball hits the batter?” That's a hit-by-pitch, I said, and the batter goes to first base. “So how come the batter gets out of the way?” he asked. “Doesn't he want to go to first?” Well, I said, if the umpire thinks he didn't try to get out of the way, then he might not let him go to first base. Besides, it would hurt. The ball is small and hard and thrown between 85 and 100 miles per hour. “Yes,” Robert agreed. “That would hurt.”

Things began to click for him when, with two outs and runners on first and second, Brennan Boesch hit a high, high pop fly to left field to end the inning. That's an out, I said.

“Ahhh!” Robert said. “So it doesn't matter how hard he hits the ball, if the fielder catches it before it hits the ground...” Yes, I said, the batter is out. You can hit the ball all the way to the wall, you can hit the ball over the wall, but if a fielder leaps up and catches it before it touches anything, it's an out. Just an out.

Robert nodded. At the same time, throughout the game, he seemed equally impressed by balls that were hit high as those that were hit far. Dull pop-ups to me were majestic things to him.

For the Mariners in the bottom of the first, Ichiro and Figgins went down quickly. When there are two outs, I said, a team is less likely to score any runs. Which is when Franklin Guttierez promptly slapped a single to left and Milton Bradley hit a line-shot homerun over the right-field wall. We stood and cheered. We bumped fists. 2-0!

The M's gave it right back with sloppy play in the top of the second. They couldn't get to ground balls. Double play balls were booted. “It seems the best plan is to hit the ball on the ground,” Robert said. Well, I said, not really. Line drives are the best kinds of hits, but those, too, can be caught for outs. There's a lot of chance in the game. You can perform well and still make an out. You can perform poorly and still get a hit.

A Tiger slapped a single to left and took a wide turn. “He was thinking about going to second,” Robert said, “but he did not want to take the risk.” Exactly, I said.

In the top of the third, the Tigers threatened again: men on first and second with only one out. But Don Kelly lined the ball to Chone Figgins at second, who doubled off Brandon Inge at first. Doubled off. OK, when the ball is hit in the air, the baserunners can only advance when...

In the top of the third, the Tigers threatened again: men on first and second with only one out. But Don Kelly lined the ball to Chone Figgins at second, who doubled off Brandon Inge at first. Doubled off. OK, when the ball is hit in the air, the baserunners can only advance when...

After that, things went quickly. We had several 1-2-3 innings. Three up, three down. I worried the game would seem long and boring to Robert but he thought it moved fine. He thought American football was long and boring in comparison. “So many timeouts,” he said.

I filled his head with unnecessary minutia:

- The Tigers were one of the original 16 major league teams, dating back more than a century, while the Mariners existed only since 1977.

- Major League Baseball didn't start playing “The Star-Spangled Banner” before games until World War I and it didn't become codified, I believed, until the late 1930s (although it's apparently World War II).

- The 7th inning stretch supposedly began when William Howard Taft, president of the United States from 1909 to 1913, went to a game and stood up after the top of the 7th and everyone followed suit—but I told him this story was probably apocryphal.

- “Take Me Out to the Ballgame,” which we sang during the 7th inning stretch, was over 100 years old.

After 9/11, I added, they also played “God Bless America” during the 7th inning stretch but that's mostly stopped. Then we talked about 9/11. He had the perspective of someone who grew up in the midst of a civil war and didn't expect life to run smoothly. “I thought, you know, this might be bad,” he said about being Lebanese. “It might be like the Japanese with internment camps. But everyone treated me nicely. I didn't have any bad incidents.”

In the end, for all of my apologies at the beginning, we watched a good game. In the 8th it was 3-3, and I was beginning to explain the concept of extra innings to Robert—who, instead of being appalled, rather liked the idea that no game could end in a tie—when, with runners on first and second and one out, Milton Bradley lined a two-strike pitch to right field. Here came Figgins from second! A play at the plate! Safe! I showed Robert the umpire calls for “safe” and “out.” I talked about how it was good that Guttierez was now on third because he had speed and might score on a sacrifice fly, which I also explained, and which was promptly demonstrated when Jose Lopez lofted a shallow fly to center. Guttierez ran. Safe! “He took the risk,” Robert said.

In the 9th, the M's closer, David Aardsma, was announced by the PA announcer with a pirate drawl (“Aarrrrr-dsma”), and to accompanying heavy metal music and heavy metal graphics on the scoreboard. “Quite a production,” Robert said, looking around. Then, referring to Shawn Kelley, who had relieved Fister in the 8th, he added, “The other guy didn't get such a welcome.”

The 9th went quickly. Avila fought off several pitches before popping out to short. Raburn smacked the ball to center but Guttierez drifted under it easily. Then Austin Jackson, who began the game with a strikeout, ended it with a strikeout. The sparse crowd stood and cheered. I looked over at Robert, who smiled.

“So we win,” he said.

We win, I said.

He looked around the field. “You know,” he said, “once you know the basics, this game isn't so difficult.”

Wednesday May 26, 2010

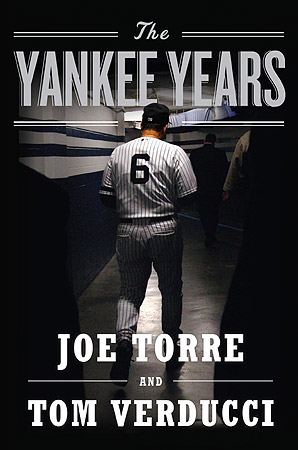

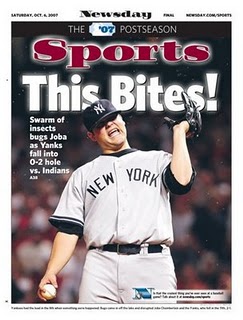

“The Yankee Years” by Joe Torre and Tom Verducci: Special YANKEES SUCK Edition

The New York Daily News called it “One of the best books about baseball ever written,” while The New Yorker named it one of its BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR, but for the rest of us, “The Yankee Years,” by Joe Torre and Tom Verducci, seems awfully schizophrenic.

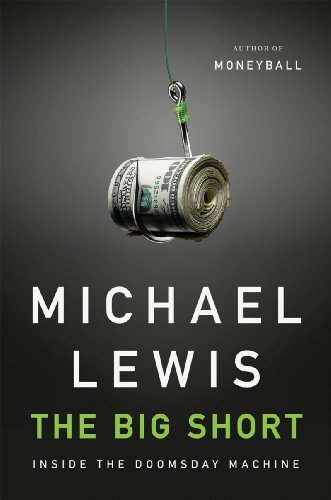

It's a mostly plodding hagiography of the 1996-2001 New York Yankees and their even-keeled manager, Joe Torre, but Verducci keeps pushing in directions that undercut the hagiography. He includes a chapter on steroid abuse, for example, that renders irrelevant the team's accomplishments. Clemens blew the Mariners away with one of the best performances in post-season history. (Yay!) But while he was on steroids. (Boo!) Oh, but don't worry, the steroids don't matter. (Huh?) He lists off the ways Michael Lewis' Moneyball changed the game—with teams like the Red Sox valuing previously undervalued stats, like On-Base-Percentage, and prospering as a result. But while Yankees' GM Brian Cashman became a quick if sloppy convert, Torre, the book's hero, never did, continuing to focus on less-measurable aspects of the game like personality and heart.

We 're reminded, again and again, of the four titles Torre helped bring to New York, as if the book were written for the Steinbrenners and Cashman, who unceremoniously cut Torre loose after the 2007 season. We're reminded, again and again, of the grinding qualities those late '90s players, such as Paul O'Neill and Tino Martinez, brought to the team, and how newer players, such as Jason Giambi and Alex Rodriguez, didn't have that same heart, and didn't care enough about the team, which is why, according to Torre, the Yankees stopped winning World Series. But this construct, which is Torre's construct, is later refuted by, of all people, Derek Jeter, who mostly blames lack of pitching for the non-title years. Verducci then backs up Jeter with stats. So which is it? Or which is it mostly? No attempt to clarify this apparent discrepancy is made.

're reminded, again and again, of the four titles Torre helped bring to New York, as if the book were written for the Steinbrenners and Cashman, who unceremoniously cut Torre loose after the 2007 season. We're reminded, again and again, of the grinding qualities those late '90s players, such as Paul O'Neill and Tino Martinez, brought to the team, and how newer players, such as Jason Giambi and Alex Rodriguez, didn't have that same heart, and didn't care enough about the team, which is why, according to Torre, the Yankees stopped winning World Series. But this construct, which is Torre's construct, is later refuted by, of all people, Derek Jeter, who mostly blames lack of pitching for the non-title years. Verducci then backs up Jeter with stats. So which is it? Or which is it mostly? No attempt to clarify this apparent discrepancy is made.

As a result, the book is a fascinating mess. It's also annoying for anyone who hates the Yankees. That's most of us.

Excerpts:

- “The [1996] postseason became a 15-game version of their regular season. The Yankees capitalized on any opening...” (p. 15) ...particularly the opening of Jeffrey Maier's glove.

- “After five games, the 1998 Yankees were 1-4, in last place, already 3 1/2 games out of first, outscored 36-15, at risk of losing their manager and letting teams like the Mariners kick sand in their faces.” (p. 42) Teams like the Mariners? How awful. I'm reminded of that Charles Atlas ad. “That team is the worst nuissance on the beach!”

- “Like Torre, [David] Cone was angered by what he saw the previous night. He watched Seattle designated hitter Edgar Martinez, batting in the 8th inning with a 4-0 lead, take a huge hack on a 3-and-0 pitch from reliever Mike Buddie—five innings after Moyer had dusted [Paul] O'Neill with a pitch.” (p. 44) Wow, Moyer dusted someone? And apparently Edgar violated one of the unwritten rules of baseball: Swinging on a 3-0 pitch when up by four runs in a stadium where David Cone threw 148 pitches and walked in the tying run in the final game of the 1995 ALDS. Edgar should know better than that.

- “'You have to find something to hate about your opponent,' [Cone said in a pre-game speech to his teammates.] 'Look aross the way. These guys are real comfortable against us. Edgar is swinging from his heels on 3-and-0 when they're up by about 10 runs!'” (p. 44) Give or take six runs.

“At some point over the 2000 and 2001 seasons, according to the Mitchell Report, Radomski provided drugs for [Yankees] Grimsley, Knoblauch, pitcher Denny Neagle, outfielders Glenallen Hill and David Justice, and later for pitcher Mike Stanton. In addition, the 2000 Yankees included three other players who later admitted their drug use (though not necessarily specific to that particular year): Jose Canseco, Jim Leyrtiz and Andy Pettitte. Most infamously, the 2000 Yankees had a tenth player who would be tied to reports of performance-enhacing drug use: Clemens.” (p. 105) We're back to the Charles Atlas ad. Mariners kick sand, Yankees beef up. “The INSULT that made steroids users out of 'Yankees'!”

“At some point over the 2000 and 2001 seasons, according to the Mitchell Report, Radomski provided drugs for [Yankees] Grimsley, Knoblauch, pitcher Denny Neagle, outfielders Glenallen Hill and David Justice, and later for pitcher Mike Stanton. In addition, the 2000 Yankees included three other players who later admitted their drug use (though not necessarily specific to that particular year): Jose Canseco, Jim Leyrtiz and Andy Pettitte. Most infamously, the 2000 Yankees had a tenth player who would be tied to reports of performance-enhacing drug use: Clemens.” (p. 105) We're back to the Charles Atlas ad. Mariners kick sand, Yankees beef up. “The INSULT that made steroids users out of 'Yankees'!”- “'Andy [Pettitte] was great,” Torre said. 'I think he taught Roger how to pitch in New York. And Roger taught Andy how to be stronger.'“ (p. 77) ”Stronger.“

- ”Pettitte was a churchgoing, God-fearing Texan, known in the Yankees clubhouse for his integrity and earnestness. If Pettitte was going to cheat, who wouldn't?“ (p. 111) Atheist bastards from Massachusetts?

- ”'It's like Bob Gibson said: “To win a game you'd take anything,”' Torre said. 'We'd all sell our souls. Winning is something that was first and foremost and that's what we wanted to do. Unfortunately, now what stimulates the need to do this is individual performance and not winning.'“ (p. 113) Ah, for the days when players took illegal substances for the good of the team.

- ”There was so much going on, so much in his head, so much emotion coursing through his body, that Clemens could not process the inventory of what was happening at that moment [when Piazza's bat shattered during the 2000 World Series] quickly enough.“ (p. 134) ”...so many steroids coursing through his body...“

- ”The Steroid Era was baseball's Watergate, a colossal breach of trust for which the institution is forever tainted. It floats untethered to the rest of baseball history, like some great piece of space junk, disconnected from the moorings of the game's statistics.“ (p. 117) Including championships in 1996, 1998, 1999 and 2000?

- The [Fenway Park] crowd arrives with the meanness and edginess of a mob.” (p. 80) Yankee crowds, bless them, arrive with smiles and pic-a-nic baskets.

- “Intimidation, and the mere threat that he could go off at any time, was part of Steinbrenner's personal and leadership package.” (p. 122) “Leadership.”

- “No 2000 World Series rings were forthcoming for the scouts, numbering about two dozen. Morale worsened when they were instructed not to bring up the subject of World Series rings at organizational meetings. It worsened still when they saw Steinbrenner cronies such as actor Billy Crystal or singer Ronan Tynan wearing World Series rings.” (p. 143) “Leadership.”

- “[In Steinbrenner's office, there was] a picture of General George S. Patton, given to him by a member of Patton's staff. It was not your typical military portrait. Patton is seen pissing into the Rhine.” (p. 467) Patton: Rhine; Steinbrenner: Baseball.

- “When Jeter was 24 years old and after the Yankees won the 1998 World Series, George Steinbrenner gave a book to him as a present: Patton on Leadership: Strategic Lessons for Corporate Warfare.” (p. 159) No bastard ever got rich by going long on subprime CDOs. He got rich by making the other poor dumb bastard go long on subprime CDOs.

- “Jeter requires fierce, unqualified loyalty from friends and teammates.” (p. 245) Baby.

- “The Yankees [after 9/11] had become not just New York's team, but also America's hometown team.” (p. 148) Fuck you.

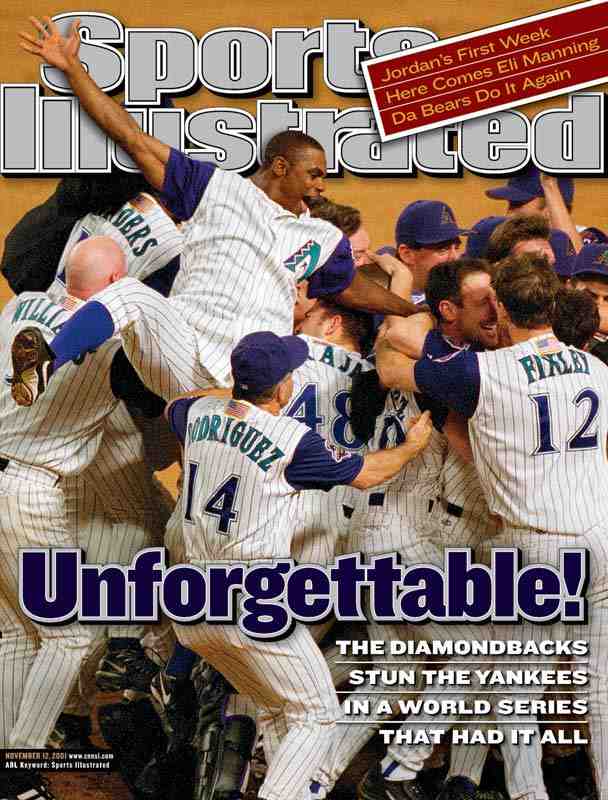

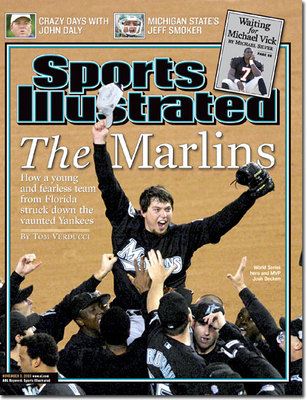

- “So it came down to this: Mariano Rivera on the mound with a one-run lead against the bottom of the Arizona lineup [in Game 7 of the 2001 World Series]. Steinbrenner was standing in front of the bathroom mirror, combing his hair, preparing to soon accept the Commissioner's Trophy for a fourth straight year.” (p. 157) Ha!

- “The [2003 World] Series could have gone either way. A sacrifice fly here, a hit there, a little back and core maintenance there, and who knows?” (p. 237) A roided-up pitcher here, a Jeffrey Maier catch there...

- “'They always play Yankeeography in New York on the videoboard. As a visiting player, you see that they get music to hit to and when we come up we get Yogi Berra and Mickey Mantle all the time,' [said Kevin Millar]. Millar walked into the office of [manager Terry] Francona [before Game 6 of the 2004 ALCS]. 'We're not hitting [batting practice] on the field today, Skip,' Millar said. 'We're not falling for any of that Yankeeography crap.'” (p. 304) Ha!

- “The Yankees were saddled not only with the worst collapse in baseball history [in the 2004 ALCS], but also the insult of having the hated Red Sox spill champagne in their stadium.” (p. 311) Ha!

- “Cashman didn't want [Ted] Lilly. He preferred [Kei] Igawa, though Igawa would cost the Yankees more money over four years ($46 million, including the $26 million posting fee)...” (p. 376) Wait for it....

- “'I caught Kei Igawa,' [bullpen catcher Mike] Borzello said... 'He threw three strikes the whole time. His changeup goes about 40 feet. His slider is not a big league pitch. His command was terrible.'” (p. 377) Ha!

- “Just the memory of [the 2003 World Series] pained Pettitte...especially that last night when Beckettt beat Pettitte and the Yankees, 2-0, in what would be the last World Series game every played at Yankee Stadium.” (p. 386) “Our sweetest songs are those that tell of saddest [Yankees] thought” —Percy Shelley (with help from Erik Lundegaard)

- “Damon's teammates grew so frustrated with him [in 2007] that several spoke to Torre out of concern that he was hurting the team. One of them visited Torre one day in the manager's office and was near tears talking about Damon. 'Let's get rid of him,' the player said. 'Guys can't stand him.'” (p. 395) Pssst...Jeter.

- “[Joba] Chamberlain, glistening from the spray and his heavy sweat, was a midge magnet. ... Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez, New York's $43 million left side of the infield, were constantly waving their gloves and throwing hands at the little midges. Fighting for their playoff lives, the most expensive team in baseball had developed into a vaudeville act.” (p. 438) This game almost made me believe in God. Or at least plagues.

- “It was 11:38 p.m. when the end came. Jorge Posada swung and missed at a pitch from Cleveland closer Joe Borowski for the final out of a 6-4 Yankees loss. It was the last pitch of the last postseason game ever played at Yankee Stadium.” (p. 462) Jor-ge! Jor-ge! Jor-ge!

- “'Guys, you're playing for the best manager you could possibly play for,' [coach Larry] Bowa told the players. 'He never rips you. He sticks up for you whether you're right or wrong. He gives you the benefit of the doubt on anything...” (p. 405) Until this book, in which Torre basically rips, among others, David Wells, Roger Clemens, Randy Johnson, Jason Giambi, Gary Sheffield, Johnny Damon, Kevin Brown, Chuck Knoblauch, Bobby Abreu and Alex Rodriguez.

- “In another era, the Yankees might have cherry-picked elite pitchers in their prime from organizations that could not longer afford them, in the same way they had plucked David Cone from the Blue Jays in 1995 and Mussina from the Orioles after playing out his contract in 2000. Instead, the Blue Jays locked up Roy Halladay, the Indians locked up CC Sabathia, the Brewers locked up Ben Sheets, the Astros locked up Roy Oswalt and the Twins locked up Johan Santana—all small-market teams who suddenly had the cash to keep their ace pitchers off the trade and free agent markets. The kicker for the Yankees was that under the revenue-sharing system they were financing some of the newfound solvency of those teams.” (p. 421) Has a more self-absorbed paragraph ever been written? The Yankees feel sorry for themselves because they can no longer treat the rest of the Major Leagues like its own farm system? Worse, it's all wrong. The true kicker, not Verducci's kicker, is that all of these pitchers, save one, are not only not “locked up” but now with other teams—including Sabathia with the Yankees. Only Oswalt is still with the Astros...and he wants out.

- “Cashman and the Yankees [in the offseason leading up to the 2009 season] only had just begun to change the story. In 12 days they spent $423.5 million on Sabathia, pitcher A.J. Burnett, who was 31 years old at the time, and first baseman Mark Teixeira, who was 28. ... All told, the Yankees spent $441 million on free agents in that one winter. The rest of the league combined spent $176 million.” (p. 486) The rigged game continues. Rooting for the New York Yankees is like rooting for Goldman Sachs.

Good times.

Tuesday May 25, 2010

Review: “El Secreto de sus Ojos” (2009)

WARNING: EL SECRETO DE MES SPOILERS

How do you keep the lovers apart? Dramatists have certainly come up with inventive answers over the years: Our families fight, it’s taking forever to return from this war, frankly my dear I don’t give a damn. The Argentinian film, “El Secreto de sus Ojos” (“The Secret in Their Eyes”), comes up with a more mundane and thus universal answer: fear, doubt, passivity. Our eyes may dance but our bodies continue in the dull directions they’re going.

The movie opens with a pivotal scene. A woman at a train station. A bearded man walking away. It feels like the 1970s. He gets on the train and as it’s pulling out she desperately runs alongside and presses her palm to his window. He does the same. She keeps running. He stands up and hurries to the caboose so he can watch her one last time as the train gathers speed and takes him away, away, away from her.

Cut to: a writer, cursing, and scribbling out that scene. Good for him.

He tries again. June 1974. A breakfast on a veranda between a young, handsome couple. They drink tea with lemon—for his sore throat. One gets the feeling it’s the last time he’ll see her.

Bah! Crumpled up.

Then a flash of memory. That same girl, bloodied, raped. The writer bows his head and closes his eyes. Is he the young man on the veranda? The rapist?

Neither. The writer is Benjamin Esposito (Ricardo Darin), a gray-haired, retired, federal agent in Buenos Aires, who is having trouble writing a novel based upon an old case, the Morales case. We see him walking into his old digs, flirting with attractive women there (“The gates of heaven have opened...” he says), then entering the chambers of an old colleague, his superior, Irene Menendez Hastings (Soledad Villamil). Her pretty eyes dance when he enters but stop dancing (and go sit in the corner) when he brings up the Morales case. That thing again? she seems to be thinking. Nevertheless she brings out an old Olivetti typewriter with a busted “a” key for him to use. We’ll see this typewriter more often, as a running gag, as the movie progresses into the past.

Neither. The writer is Benjamin Esposito (Ricardo Darin), a gray-haired, retired, federal agent in Buenos Aires, who is having trouble writing a novel based upon an old case, the Morales case. We see him walking into his old digs, flirting with attractive women there (“The gates of heaven have opened...” he says), then entering the chambers of an old colleague, his superior, Irene Menendez Hastings (Soledad Villamil). Her pretty eyes dance when he enters but stop dancing (and go sit in the corner) when he brings up the Morales case. That thing again? she seems to be thinking. Nevertheless she brings out an old Olivetti typewriter with a busted “a” key for him to use. We’ll see this typewriter more often, as a running gag, as the movie progresses into the past.

It’s 1974 and Esposito, a federal agent, but more bureaucrat than Bond, argues with colleagues over who gets a new case. No eager beavers here. He and his colleague, Pablo Sandoval (Guillermo Francella), an offhandedly smart man with a drinking problem, draw the short straw, but as soon as Esposito arrives on the crime scene and sees the woman cold and naked on the bed (“Liliana Coloto, 23,” he’s told. “Schoolteacher. Recently married”) he can’t let go of the case. His turnaround is immediate but unexplained. Because the woman is so young and beautiful? Because it’s such a horrible crime?

When informed, the husband, Ricardo Morales (Pablo Rago), seems stunned and talks about how she liked to watch the Three Stooges. Is he a suspect? There are two construction workers working on the building. Are they suspects? It’s not until Esposito sits down with a photo album—which charmingly includes a vellum overlay that identifies all of the people in the pictures—and spots, in shots from her hometown, the same man, Isidoro Gómez (Javier Godino), staring at her, that he has something tangible to go on. It’s the secret in Gomez’s eyes that’s not really a secret. As with most secrets in the movie.

From Gomez’s mother, Esposito and Sandoval learn that Gomez recently moved to Buenos Aires (ah ha!), and is working on a construction site (ah-ha-er!), but he seems to have vanished. They steal letters he sent his mother but they hold no clue, and superiors within Esposito’s office close the case. At the train station, a year later, Esposito runs into, of all people, Morales, who shows up several times a week, after work, waiting for Gomez. This dedication, this passion, reignites Esposito’s, who convinces Hastings, against her superior’s wishes, to reopen the case. But it’s Sandoval who figures out the clue in the letters. (Because there’s always a clue in the letters.) The men Gomez references are not from their hometown; they’re futbol players; and following the movie’s proposition that a man can change many things—his name, his hair—but not his passion, they stake out stadiums. It’s like needle-in-a-haystack, but on the fourth try they find the needle.

Gomez, under questioning, gives up nothing, and Sandoval is off drinking so the good cop/bad cop routine won’t work—until Hastings notices Gomez staring at her blouse and plays bad cop by impugning his manhood (in fairly obvious ways). He falls for it, slugs her, and confesses to the rape/murder to regain his manhood. Case closed. “He’ll get life,” Esposito tells the husband. “Let him grow old in jail,” Morales says. “Live a life full of nothing.”

A year later, Gomez is spotted, not only not in prison, but guarding the president of Argentina, Isabel Peron. Seems in prison he became a snitch for the fascists and was rewarded. Now the fascists are coming for Esposito. They kill Sandoval by mistake and Hastings takes Esposito to the train station so he can get away. It’s there that, embracing, all of their feelings for each other, the secrets in their eyes that aren’t really secrets, spill out; and it’s there that the opening scene—woman running alongside train—is replayed in all of its melodramatic glory.

And that’s pretty much it in terms of backstory. The passion they feel for each other—which, within the story’s construct, can’t change—is put on the back burner. Esposito leaves, lives elsewhere, gets married. Hastings gets married. Question: When they meet at the beginning of the movie, in her chambers, is this the first time they’ve seen each other since the train station? Either way, they continue to tamp down their passion. They pretend otherwise. Like most of us, I suppose.

“El Secreto” is both love story and mystery, and the two are connected in different and not always comfortable ways. The looks Gomez gave Liliana Coloto in photos? Esposito gives Hastings the same looks. Esposito also seems to channel his passion for Hastings into the investigation—which may be why Hastings is always disappointed that he’s still obsessed with the investigation. Me, she seems to be thinking. You should be paying attention to me.

Writing the novel about the case is actually Esposito’s way of continuing the investigation, of finding out what exactly happened to Gomez, and in this regard he visits Morales, now living deep in the countryside. He’s older now, bald, suspicious, but he admits, to this former federal agent, that decades ago he kidnapped Gomez, took him by a railroad track, waited for the noise of a passing train, and put four bullets into him. Case closed! Except as soon as you see his circumstances (living far away from everyone else), and as soon as you recall his earlier lines (“Let him grow old in jail. Live a life full of nothing”), you assume he didn’t kill Gomez; you assume he’s imprisoning him. Which turns out to be the case. Esposito returns at night and finds the old murderer/rapist imprisoned, and a ghost of a man. “Please,” he says to Esposito. “At least tell him to talk to me.” It’s exquisite revenge ruined by how easily we anticipate it—and by the fact that, Morales, in guarding Gomez, is wasting his life, too.

But what now? Esposito had channeled all of his passion into this one case, and the case is closed. He’s also spent the movie keeping his own passion imprisoned. Has he learned? Of course he has. A note he wrote to himself earlier reads “Te mo” (I fear), but now, at the end of the movie, he adds an “a,” making it “Te amo” (I love you); and with that he runs to Hastings’ chambers, where she sees, finally sees, the unguarded look of love in his eyes, and cuts to the chase. “There will be difficulties,” she says. “I don’t care,” he says. They close the door. La final.

“El Secreto,” which won the best foreign language film at the 2009 Academy Awards, is both complex in structure and crowd-pleasing (it’s about love); and, as a writer, how could I not like the early, crumpled-up scenes? At the same time, it feels like the motivations of the characters are too big and clunky to fit into its intricate plot structure. Why, for example, does Esposito get so obsessed with this case? And if Gomez is a man obsessed with one girl, Liliana, as the photos imply, why does he quickly become just a generic creep?

But the bigger problem—besides seeing Gomez’s end far in advance of Esposito—is, sadly, that crumpled-up first scene, the farewell at the train station. The moment Esposito is fleeing the fascists is the moment he realizes Hastings loves him back. But he lets her go. He leaves for 10 years. He never gets in touch with her. Why? Because he’s afraid for himself? Because he’s afraid for her? Because he doesn’t want to implicate her? But she’s already implicated. She was the one who played bad cop to Esposito’s good cop, after all. She humiliated Gomez. If Gomez and his goons are going after him, why wouldn’t they go after her? Because of her social standing? Does that really make her safe? Let’s quote Michael Corleone: “If anything in this life is certain, if history has taught us anything, it’s that you can kill anyone.”

What keeps the lovers apart? Fear, doubt, passivity. At the train station, doubt is removed to double-down on fear, but that doesn’t excuse the passivity. In true love stories, both real and imagined, men must go through hell for their love, to prove their love. Esposito? He can’t even be bothered to get off the train.

Monday May 24, 2010

"Shrek" Sinks Because "Shrek" Stinks

Dreamworks' "Shrek Forever After" opened with the third-highest opening weekend of the year—behind only "Iron Man 2" and "Alice in Wonderland"—with over $70 million domestic (estimated).

A triumph? Not really.

Here are the opening weekends for the four "Shrek" movies. All numbers are adjusted to 2010 dollars:

* Top Critics Only

** All numbers are adjusted to 2010 dollars

That's quite a comedown.

Obviously new films tend to open weaker than sequels, which is what happened with the first "Shrek." But because "Shrek" was good (86% rating on Rotten Tomatoes) it went on to gross $375 million, or no. 3 for the year.

And because "Shrek" was good, its sequel, "Shrek 2," opened gangbusters: $138 million. And because "Shrek 2" was good (88% rating on RT) it went on to gross $564 million, or no. 1 for the year. In fact, until "Dark Knight" and "Avatar" came along, it was the no. 1 movie of the decade.

And because "Shrek 2" was good, its sequel, "Shrek the Third" opened gangbusters: $140 million. But because "Shrek the Third" wasn't good (49% on RT) it went on to gross only $372 million. I know: "only." But that's a $200 million drop from the previous film.

And because "Shrek the Third" wasn't good, its sequel "Shrek Forever After," opened with half the numbers of "Shrek the Third": $71 million. And because "Shrek Forever After" isn't good, either (40%), I assume it'll gross even less. Will it gross $250 million? Will it outdo "How to Train Your Dragon," which is already at $210 million?

Other factors could be at work, of course. The world's complex. Maybe there were simply better options this weekend. Maybe people are finally tired of this 10-year-old franchise. Maybe we don't have the patience for any fourth movie.

But in general I think the above is how moviegoing works—and it tends to be ignored by the powers-that-be. If you keep making a quality version of a beloved product, people will show up. Once the quality slips, the audience slips.

BTW: When referring to "good" and "bad" versions of "Shrek," I'm talking about the general critical reception, which, I argue, and have argued, is on par with general audience reception and word-of-mouth. Me, I only saw the first "Shrek," which I didn't like.

Look, Donkey! Maybe people are finally sick of us!

Sunday May 23, 2010

Target: Fun

Earlier this month I visited friends and family in Minneapolis and took in a game at the new Target Field. It's a great park, surprisingly compact, with narrow foul lines and grandstands right on top of the action. We sat in the left-field bleachers, third-deck, with the Hale Elementary crowd (my nephews' school), which is about as far away as you can get from the action, and we didn't seem that far from the action. It's a vertical stadium, I heard Twins right fielder Michael Cuddyer say the other day, where the winds are trapped and swirl around on the field. It wasn't windy where we were, but man was it cold. It was the day after the first rain-out in Minnesota in 20 years, and temps stayed in the 40s throughout the game. We bundled up, I bought a Twins wool cap at the park, but we were still chilled. Occasionally, to warm up, we'd leave our seats and stand under the heaters outside the Town Ball Tavern. I know: Bud Grant wouldn't approve. But this is baseball.

Here's hoping for a World Series in Minnesota. With snow. To point out the absurdity of Bud Selilg's post-season schedule.

My nephew, Ryan, 6, en route to the game.

A VIP room on the second deck, where we weren't allowed (not VI enough), but which has the decency to plaster their outer walls with Minnesota heroes: Tony Oliva and Harmon Killebrew.

My father and I walked around the stadium for an hour before gametime—both to see the place and stay warm. Here he is on the second deck on the third-base side, enjoying a rare moment of sunshine. “Minnie” and “Paul,” the original Twins, shaking hands over the Mississippi river, rightly lord over center field.

Outside the Town Ball Tavern, photos of Minnesota “town ball” teams from the turn of the last century are displayed—including this suprisingly integrated team, with three black ballplayers, from the 1910s.

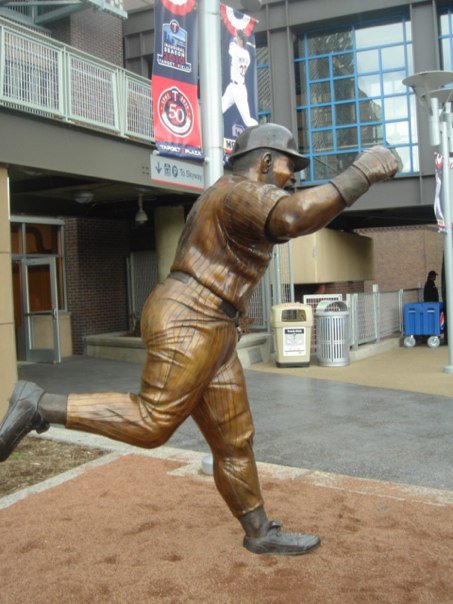

Two Minnesotans exulting: Ryan, in the middle of a 2010 loss to the Orioles, and Kirby Puckett rounding the bases after his walk-off homerun in Game 6 of the 1991 World Series: “Jump on my back, I'll carry you,” he said before the game.

The statue of Harmon Killebrew, who hit 573 homeruns and retired fifth on the all-time homerun list in 1975, behind only Aaron, Ruth, Mays and Frank Robinson. Ryan, emulating, hitting his first.

Saturday May 22, 2010

Waiting for a Superman (Movie)

The other day on Facebook I mentioned that I've only bought eight new songs this year—and it's nearly the end of May. My friend Andy, recently of Hanoi, suggested the latest Iron & Wine collection, which I promptly bought, and which includes this cover of the Flaming Lips' song “Waiting for a Superman.” It's quite beautiful. You can listen to it here, but, as always, I recommend buying. Support your local artists. Even when they're not local.

Here are the lyrics:

I asked you a question

I didn't need you to reply

Is it getting heavy?

But then I realized

It's getting heavy

Well I thought it was already as heavy as can be

Is it overwhelming

To use a crane to crush a fly?

It's a good time for Superman

To lift the sun into the sky

Because it's getting heavy

Hell I thought it was already as heavy as can be

Tell everybody

Waiting for Superman

That they should try to

Hold on the best they can

He hasn't dropped them, forgot them or anything

It's just too heavy for Superman to lift

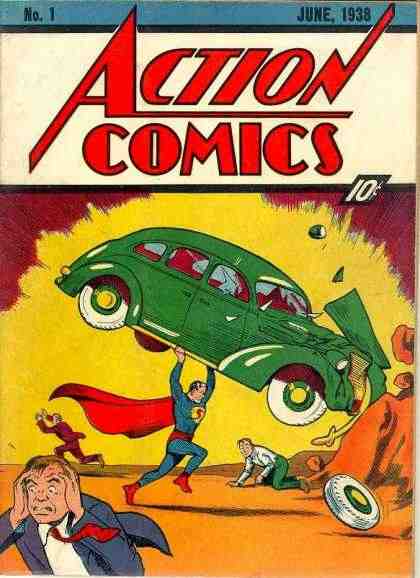

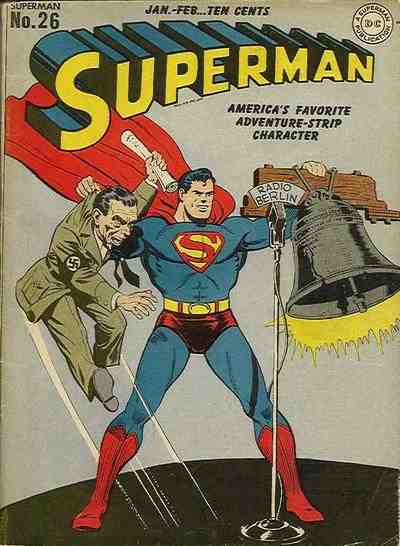

The people working on the next Superman movie should listen to this song over and over. The question they need to answer, to make the movie work, is right here: What's too heavy for Superman to lift?

Answer that and you've got a story.

Oh, and I'm still taking suggestions for new music if anyone's got ideas.

Things Superman can lift: a car, a lion, Goebbels.

Friday May 21, 2010

Dowd on Dowdy

This is one of the dumber paragraphs I've read this week, and, big surprise, it comes from Maureen Dowd. Lamenting media coverage of Elena Kagan, Dowd dissects the difference between "single" and "unmarried" and writes of the double standard women endure:

But if you have a bit of a weight problem, a bad haircut, a schlumpy wardrobe, the assumption is that you’re undesirable, unwanted — and unmarried.

Not only is this not a double standard—since it applies to men, too—but it seems the very definition of undesirable in our culture: fat and dowdy.

Dowd's real complaint is that a male version of Kagan—successful, outgoing, but no George Clooney—would still be seen as a sexual being, but this is because of a different double standard: the premium women place on male success. The problem, if you even want to view it as a problem, is yours, Maureen.

The whole column is an embarrassment. I don't doubt news coverage of Kagan has been awful, but Dowd's corrective is no corrective.

Thursday May 20, 2010

All-Star Game: Vote Early and Often

How odd that they encourage us to vote more than once for the All-Star Game. Is Bud playing the numbers game? Twenty-three million ballots cast! A new record! People care! Sure, but 10 million were cast by Joe Schlumpfo, unemployed, in Des Moines.

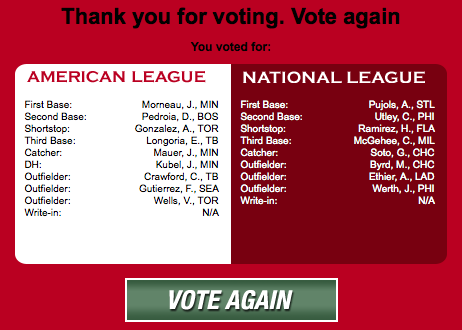

Here's the ballot cast by Erik Schlumpfo, writer/editor, in Seattle:

I'm Twins-heavy, I know, and Yankees-deficient, but that's the fun of it. Kubel gets in just for the grannie off Mo.

Go here to vote—under the "related coverage" box. Vote early and often. Let's keep the starting nine Yankee-free.

Wednesday May 19, 2010

Review: “Iron Man 2” (2010)

WARNING: HEAVY METAL SPOILERS

I thought it wouldn’t work. I thought too many villains and partners (Whiplash and Black Widow and War Machine and Nick Fury?) would sink the thing, like they sank “Batman Forever,” and “Batman and Robin,” and “Spider-Man 3.” Instead the movie plays like a good three-issue arc of a 1970s comic book. Plus we’re teased with more Avengers stuff—a little Captain America here, a little Thor there—but, FYI, you have to stay through the credits for a peek at some aspect of the Son of Odin. (Psst: it’s not Chris Hemsworth.)

The movie opens with Tony Stark (Robert Downey, Jr.) on top of the world but with a “Top of the World, Ma!” quality to him. He’s rich, powerful, and as Iron Man he’s brought about world peace, but he’s more self-destructive than ever. Maybe because he’s self-destructing. His blood is slowly being poisoned by the whatchacalm in his chest that turns him into Iron Man. He tests himself. Blood toxicity: 19%. Then 24%. Then 53%. Oops.

The movie opens with Tony Stark (Robert Downey, Jr.) on top of the world but with a “Top of the World, Ma!” quality to him. He’s rich, powerful, and as Iron Man he’s brought about world peace, but he’s more self-destructive than ever. Maybe because he’s self-destructing. His blood is slowly being poisoned by the whatchacalm in his chest that turns him into Iron Man. He tests himself. Blood toxicity: 19%. Then 24%. Then 53%. Oops.

Meanwhile, three other things threaten to take him down:

- In Russia, Ivan Vanko (Mickey Rourke), the son of his father’s former business partner, who blames the Starks for his father’s boozy death, uses age-old blueprints to come up with his own whatchacalm in his chest and turns himself into the supervillain Whiplash;

- In Washington D.C., a U.S. Senator, aptly named Stern, but played comically by Gary Shandling, demands that Tony Stark turn over the Iron Man outfit to the U.S. Army in the interests of national security; and

- Stern’s military-industrial-complex partner, Justin Hammer of Hammer Industries (Sam Rockwell), jealous to the max, tries whatever he can to outdo his rival.

All of these threats coming down on him at once actually play to the strengths of the lead actor. Downey, Jr. has always felt like a pursued man to me, as if he were racing, physically and psychologically (mostly psychologically), to stay ahead of everything that wants to overcome him. So it makes sense to make Stark a pursued man, too, who keeps distracting himself with the next big thing. He begins a year-long Stark Expo in Flushing Meadows, NY, he testifies before the Senate Armed Services Committee and refuses to share his toys, he gives control of his company to his assistant, Pepper Potts (Gwyneth Paltrow), and he races cars at the Grand Prix in Monte Carlo. This last is where Whiplash appears and takes out two cars, including Stark’s, and then strolls menacingly forward. You can only run so fast, Tony. Things always catch up. Even when they stroll.

Can I pause here to thank Darren Aronofsky? Without Aronofsky’s “The Wrestler,” Rourke’s career wouldn’t have been resurrected enough for studio execs to allow him to play an A-list role in an A-list movie, and he’s a perfect counterpoint to the star. Stark/Downey, Jr. is a babbler, whose mouth, working overtime, still can’t keep up with his mind. Rourke/Vanko is the opposite. Everything he does is slow. He walks slowly, talks slowly, shifts his toothpick from one side of his mouth to the other slowly. He serves his revenge cold. If Stark’s pace is the result of frenetic intelligence—one thought pushing out another—Vanko’s leisurely pace almost feels like wisdom. When Stark visits Vanko in his Monte Carlo jail cell, he talks shop, “Pretty decent tech,” etc., but Vanko has the bigger picture in mind. “You come from a family of thieves and butchers,” he says, with that deliciously thick Russian accent. “And like all guilty men, you try to rewrite your history, to forget all the lives the Stark family has destroyed.” He is exactly what you want in a villain. Not someone to boo and hiss, but somebody almost more admirable than the hero. Someone to make you consider switching sides.

He's smart, cool, slow, and likes birds. Who wouldn't root for him?

As Stark’s enemies get closer, his self-destruction gets worse. He whoops it up at his birthday party—his last, he believes—and skeet-shoots with his Iron Man blasters to the delight of half-naked girls. He battles his friend, Lt. Col. James “Rhodey” Rhodes (Don Cheadle, taking over, for some reason, from Terrance Howard), who steals one of his Iron Man suits and delivers it to the U.S. military, who delivers it to Justin Hammer. Nice friend. Nice military-industrial complex. It’s the second time Rhodes has played sap for Hammer against Stark. To be honest, it’s not much of a role.

There’s other silly stuff. Apparently Pepper and Natalie don’t get along...until they do. When Tony is ready to tell Pepper he’s dying is the exact moment she’s unwilling to listen to him. There are father issues—because there are always father issues these days—and the old man (John Slattery of “Mad Men”), via a scratchy film from the 1960s, gives his son a 40-year-old puzzle that provides...wait for it...the key to curing the toxicity in his blood! That’s some foresight from Daddyo. Not to mention a vague ripoff of “Da Vinci Code” and “National Treasure.” Note to Hollywood: The world isn’t a puzzle. Everything doesn’t fit together. Your usual lies are lies enough.

I thought the casting of Scarlet Johansson as Black Widow was silly, too, but thanks to personal trainers and special effects it works. And lord knows she works that suit. There’s a scene where she enters a diner from behind that’s just... Mercy. At the same time, is there too much blankness in her eyes? Something passive and uncalculating? Samuel L. Jackson doesn’t seem to be having as much fun with Nick Fury as he should, while Cheadle, ever dour, looks positively trapped when his visor rises in his Iron Man suit. Gwyneth? Another thankless role. She’s an assistant turned CEO, and love interest to a man who doesn’t seem interested in love. At the end of “Spider-Man 2” we want, almost desperately, for Peter Parker and Mary Jane to get together, but there’s so little chemistry between Stark and Potts that when they kissed I thought, “Oh, right. He’s supposed to love her.”

Rockwell as Hammer is a delight: all bullying CEO bluster. He's the hollow man, as hollow as an Iron Man suit. The screenplay by Justin Theroux isn’t bad, either. There’s a nice play on the words Google and ogle, Stark dismisses Fury’s “Avengers” overtures thus, “I don’t want to join your super-secret boy band,” and when Hammer introduces a sexy Vanity Fair reporter to Tony, we get this exchange:

Justin Hammer: Christine's doing a spread on me.

Pepper Potts: She did a spread on Tony last year.

Tony Stark: Wrote an article too.

Director Favreau, also playing the hapless Happy Hogan, Tony Stark’s chauffer, gives us a sense, more than in most superhero movies, what it’s like to be a civilian in the midst of a superhero battle. Gods battle above you. Buildings fall around you. It's scary stuff. It works. The movie, mostly thanks to Downey, Jr. and Rourke, works.

But where to go from here? How about away from the East-West dynamic (too Cold War) and toward a greater Mideast-West dynamic? Or instead of the cartoonish jealousy of a Justin Hammer, why not have genuine worry from the military-industrial complex about the money and influence they’re losing in the age of Iron Man? Along with their misconceived attempts to get it back?

Of course I’d happy if the next movie simply went in the direction of one call...

'Nuff said!

Tuesday May 18, 2010

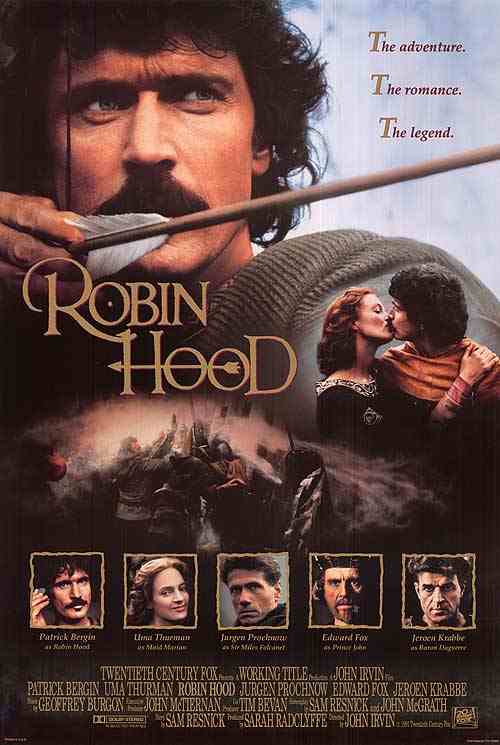

Armond White's Review of “Robin Hood” —with Footnotes

Every Man for Himself

Russell Crowe plays Ridley Scott’s everyman again—this time with arrows

By Armond White

At a reported cost of over $200 million, according to the London Telegraph, Ridley Scott’s Robin Hood refutes the old altruistic axiom “rob from the rich and give to the poor.” All the charm and meaning has been taken out of this reboot. It’s now a “history,” opening with a detailed inscription to establish the 12th-century tale’s seriousness: “In times of tyranny and injustice, where law oppresses the people, the rebel takes his place in history.” In other words, Gladiator II.

I assumed the title card was an homage to earlier cinematic version of “Robin Hood” rather than a call to seriousness. Who knows? But every major “Robin Hood” movie has begun with such a description.

Russell Crowe once again plays Scott’s everyman hero who rises above his taciturn machismo to avenge dreadful memories—clever shtick for the wealthy duo that like to pretend they’re doing something besides just raking it in.

Question: how is this not a potential criticism of any movie in which a star plays an everyman? Movie stars are wealthy; everymen are not. Was it shtick for Crowe to play an everyman hero in “L.A. Confidential”? And what’s the point of guessing at the motivations of Crowe and Scott? What does that have to with what’s on the screen?

Their nouveau-riche narcissism imagines having a populist purpose, yet the clichés of Robin Longstride’s archery skills, put to use in the English army’s campaign against the French while, back home, Marian Locksley (ludicrous Cate Blanchett) tills her impoverished, overtaxed fields, don’t speak for the people, except in distant, almost invisible metaphor.

I had to read this sentence several times to fathom its meaning... and I still don’t quite fathom its meaning: “...the clichés of Robin Longstride’s archery skills....don’t speak for the people...”? WTF? In general, White seems to be saying that the film pretends to be populist but isn’t. Maybe: It’s the one Robin Hood movie in which King John and Robin Hood fight side-by-side. On the other hand: It’s the only Robin Hood movie where Robin is a commoner, where none of the royals, including Richard, are particularly worthy, and where the end game is not the return of King Richard (and a more benevolent monarchy) but the adoption of the Magna Carta (and the beginning of liberty for all). Some might consider this a populist message.

And the motto these oppressed Brits live by (“Arise and arise until lambs become lions”) isn’t about Tea Party insurrection; it merely replaces poetic generosity with vengeance.

Does White want the motto to reflect Tea Party insurrection? Admittedly “Rise and Rise Again” is an odd slogan for this movie, since Crowe as Robin is always a lion, and so doesn’t need to rise and rise again to become one. But it works if one thinks of the Magna Carta as the end game. We all must rise again until we stop being sheep and become men.

Scott and Crowe return to Gladiator’s violent formula because the high-life confessions of their “A Good Year” collaboration didn’t click. But they also seem to be chasing after Antoine Fuqua (the director Scott replaced on American Gangster) in the way Robin Hood repeats the insipid realism of Fuqua’s 2004 King Arthur, the grungy, anti-poetic reboot of Arthurian tales. Both films represent a dullard’s version of history; Hollywood’s commercial calculation has become so obvious that it removes beauty from storytelling. Screenwriter Brian Helgeland’s period setting over-simplifies the context for violence—reusing his Braveheart formula but without director-star Mel Gibson’s conviction.

Why would they be chasing after Fuqua—“King Arthur” failed miserably. And what exactly is the commercial calculation in removing beauty from storytelling? Let’s face it, there’s not much in the plot here that is commercial. It is, in fact, the least commercial of all the Robin Hood movies since it never even gives us Robin Hood.

Look at Scott’s superficial “beauty”: a couple of dusk landscapes (amazingly subtle lighting by John Mathieson) and a splendid view of French ships roiling on blue, misty waves. But these are not “cinematic” images; they’re mini TV commercials that lack existential vision. Ultra-hack Scott reverts to the slickness of his advertising background. TV imagery has pervaded cinema to the point that Scott doesn’t balance his over-cropped TV-style close-ups with the postcard vistas. Like Gladiator’s jarring F/X, it shows Scott’s disrespect for cinema.

White piles insults upon opinions here. It’s all air. There’s nothing to even push against.

Fake beauty and fake history rob Robin Hood of previous moral value. It’s no longer “legendary” because Scott and Helgeland’s sham realism trivializes history. They pretend how history happened (Monty Python-style) but their embarrassing, anachronistic rip-off of Saving Private Ryan’s beachfront battle scene shows no feeling for how history is constructed and passed down through ritual, repetition and affection. An abstract end-credits sequence is more imaginative (it’s in the style of Scott’s Scott Free company logo). In place of inspiration, Robin Hood has the bloat of a 1960s roadshow presentation: Costly, overlong but with no intermission—or reprieve.

The previous moral value of Robin Hood stories has been greatly exaggerated. In older stories, Robin is basically a noble fighting a disreputable royal until a better, war-mongering royal returns, so life can continue as is. This Robin is using his luck to actually push for reform. I’m not saying Scott’s “Robin Hood” is a good movie. I’m saying White, in his ad hominem attacks, doesn’t delineate any of the reasons why it’s not good.

Back in '38, when, according to White, “Robin Hood” had a true populist message: to fight and bow before a benevolent, warmongering monarch like King Richard the Lionheart (Ian Hunter, above).

Monday May 17, 2010

Lancelot Links

- Fascinating post by Sex in a Submarine's William Martel on the long, sad road "Robin Hood" took to the big screen. Once upon a time, he says, there was a much ballyhooed screenplay called "Nottingham," in which the RH tale is told from the Sheriff's perspective. Russell Crowe signed to star as the Sheriff. They just needed a director...

- Check out Felix Salmon's thoughtful New York Times Op-Ed on the future of the futures market for Hollywood movies. He thinks the studios, who are against it, and lobbying Congress to make it illegal, have the most to gain from it. Me, it might be the one futures market I'd have a chance in hell in.

- And the battle to reign in copyright infringement in the digital age continues. The FCC has allowed studios to encode video-on-demand with a signal that prevents set-top boxes from recording that content, while music publishers are suing profitable Web sites from posting song lyrics without license. Quote from David Israelite, the chief executive of the National Music Publishers’ Association, which represents more than 2,500 publishers: "The digital age has provided a chance to re-evaluate the value of the words." He adds, "[It] hasn’t been exploited very well." Understatement of the year, bro.

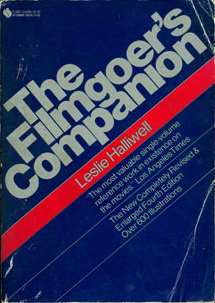

Via IMDb.com, Jessica Barnes of Cinematical lists her favorite books about movies, and readers chime in. Off the top of my head, I'd go with: David Thomson's "The Whole Equation," Edward Jay Epstein's "The Big Picture," Mark Harris' "Pictures at a Revolution," Peter Biskind's "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," and David Mamet's "Bambi vs. Godzilla." If we're talking influential, then my no. 1 is "The Filmgoer's Companion," Fourth Edition, 1974, by Leslie Halliwell. Dog ears should be so dog-eared.

Via IMDb.com, Jessica Barnes of Cinematical lists her favorite books about movies, and readers chime in. Off the top of my head, I'd go with: David Thomson's "The Whole Equation," Edward Jay Epstein's "The Big Picture," Mark Harris' "Pictures at a Revolution," Peter Biskind's "Easy Riders, Raging Bulls," and David Mamet's "Bambi vs. Godzilla." If we're talking influential, then my no. 1 is "The Filmgoer's Companion," Fourth Edition, 1974, by Leslie Halliwell. Dog ears should be so dog-eared.- Via a Sean Axmaker FB status update, here's Richard Thompson singing, believe it or not, "Oops... I did it again." He nails it, too.

- Is "This Much I Know" a regular Guardian column? Good idea—even if the title reminds me of Homer Simpson botching the title of that right-wing record album, "This [sic] Things I Believe." Guardian's latest version is from Malcolm Gladwell. Of the things he knows this much, some are interesting ("We need more generalists"), some are obvious ("I prefer great songwriters to politicians"), and one, near the end, just feels wrong: "Hollywood is strangely indifferent to questions of faith, while the rest of America is consumed by them." Counter-argument: Most of America isn't consumed by the questions of faith so much as by the desire to see their faith validated. Hollywood used to do this, with their Biblical epics in the '20s, '50s, '60s, but it's a bigger world now, a bigger market, and while sometimes the Christians come out to spite those they feel are spiting them ("The Passion of the Christ"), mostly they just stay at home ("The Nativity Story").

- Good article on The Atlantic site on what's wrong with "Glee."

- Also from The Atlantic: Odd, creepy encounter between Donald Rumsfeld and Alex Gibney, documentarian ("Taxi to the Dark Side"), at the White House Correspondents' Dinner. Rumsfeld: "Abu Ghraib... That was a terrible thing." OK, so maybe that was the understatment of the year. Not a big fan, by the way, of the WHCD. It always has a "Nero fiddles" feel. With one exception.

- Hawaii's had enough of the Birthers. And who hasn't?

- The best lines I've read on the Junior-sleeping-in-the-clubhouse controversy is in this post from a New York Yankees fan. Read it and laugh. Or weep. Or just shake your head sadly.

- Finally, here's a special "Iron Man 2" quote for the New York Yankees and their invincible closer Mariano Rivera: "If you can make God bleed, people will cease to believe in Him. There will be blood in the water. And the sharks will come." Touch 'em all, Jason Kubel!

Sunday May 16, 2010

Robin Hood — Libertarian?

Here's my favorite part of A.O. Scott's review of the new “Robin Hood”:

Meanwhile — and believe me, there is a whole lot of meanwhile in this crowded, lumbering film —...

Here's my least-favorite part:

You may have heard that Robin Hood stole from the rich and gave to the poor, but that was just liberal media propaganda. This Robin is no socialist bandit practicing freelance wealth redistribution, but rather a manly libertarian rebel striking out against high taxes and a big government scheme to trample the ancient liberties of property owners and provincial nobles. Don’t tread on him!

Yes, Robin Hood, in legend, is most famous for robbing from the rich and giving to the poor, but Hollywood, liberal Hollywood, has never followed suit. In the Fairbanks version in 1922, Robin and his men sing about it (“We rob the rich, relieve distressed...”), and an arrow quivers close to “the Rich Man of Wakefield,” but that's about it. Otherwise they're against Prince John's excessive taxes. The Flynn version during the Depression? That caravan they rob is full of Prince John's tax money. Costner? He does rob a wealthy man, and takes the necklace off of his comely daughter, but he, too, is mostly about getting back tax money. Ditto Patrick Bergin the same year. You can take issue with it, but don't pretend it's anything new. Hollywood always makes it personal, not political.

Plus the libertarian line is just silly. The libertarian assumption is that we're all free and government enslaves us. The 12th century assumption is that we're all enslaved, at the whim of a king who is chosen by God, so Robin tries to use government, i.e., kingly decree, to free us. We're talking different planets.