Sports posts

Monday April 03, 2023

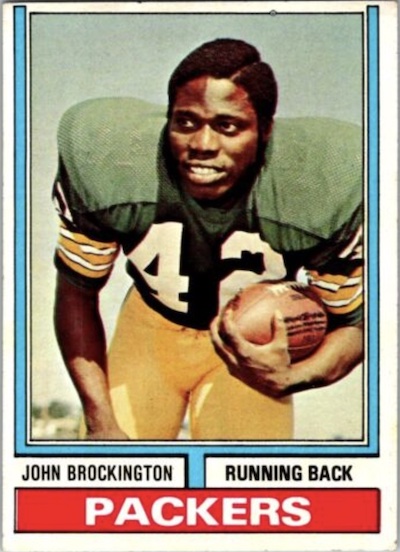

John Brockington (1948-2023)

This is a little weird, but John Brockington was the first Black guy I remember parting his hair. I was born in 1963, became cognizant (more or less) in the late ’60s, a time of Oscar Gamble-ish natural afros, and Brockington had that, but tighter, shorter. And on his 1974 football card, a posed shot, helmetless, his hair was parted. “Huh,” I thought. “Didn’t know that was an option.”

When I first became a football fan, around 1972 or so, the Green Bay Packers were past their Vince Lombardi-era, “frozen tundra of Lambeau Field” heyday, but they had Brockington. He was the best player on mediocre Packer squads from 1971 to 1975. His rookie year, 1971, he rushed for 1,000+ yards and was Rookie of the Year three ways: AP, UPI, Sporting News. He made the Pro Bowl the next two years, rushing for 1,000+ each time. According to his New York Times obit, it was the first time in NFL history that a running back broke the 1,000-yard barrier in each of his first three seasons.

When I first became a football fan, around 1972 or so, the Green Bay Packers were past their Vince Lombardi-era, “frozen tundra of Lambeau Field” heyday, but they had Brockington. He was the best player on mediocre Packer squads from 1971 to 1975. His rookie year, 1971, he rushed for 1,000+ yards and was Rookie of the Year three ways: AP, UPI, Sporting News. He made the Pro Bowl the next two years, rushing for 1,000+ each time. According to his New York Times obit, it was the first time in NFL history that a running back broke the 1,000-yard barrier in each of his first three seasons.

1974 is when he began to falter. His rushing attemps were about the same (266) but his average per went down by a yard: from 4.3 to 3.3. The next year, his attempts were cut in half and his average dropped to 3.0. Was it the Packer offensive line? Was he losing a step? Can’t imagine that grind. After one game in 1977, he was traded to Kansas City. That was his last season.

The Packers went to the postseason once in his run—1972, and lost 16-3 to the Washington Redskins in the divisional round. The 1970s was the era of Minnesota Vikings dominance—divisionally speaking, anyway. The Pack didn’t make it back until 1982, and then not again until ’93.

I remember he was my friend Dave Budge’s favorite player. I wonder if he wore #42 for Jackie?

Saturday March 11, 2023

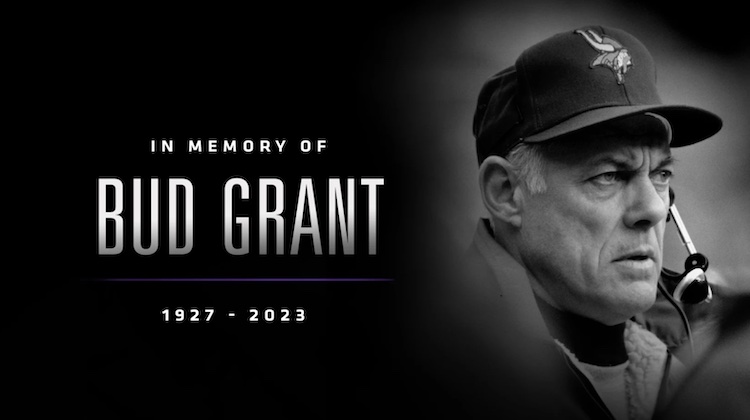

Bud Grant (1927-2023)

Is there a more Minnesota moment than 88-year-old Bud Grant trotting out for the coin toss in the 2016 playoff game between the Seattle Seahawks and the Minnesota Vikings? It was Jan. 10, outdoors in Minneapolis, so the gametime temperature was -6 degrees. And Bud was out there wearing a short-sleeved shirt.

Again: It was minus six degrees.

Bud Grant's 1970s Minnesota Vikings were famous for not showing off. They didn’t spike the ball, didn’t touchdown dance, and their coach on the sidelines never betrayed an emotion. But an octogenarian trotting out in a golf shirt for the third-coldest playoff game in NFL history? Yeah, that’s how Minnesotans show off. It’s not “Hold my beer,” it’s “Hold my jacket.”

As a kid, I thought Bud Grant was ancient, but, like Sparky Anderson, he was simply prematurely gray. He was in his early 40s when I began watching the team in 1971. Everything about him was steel: His hair, his eyes, his demeanor. Although according to the obits, he didn’t coach that way. He was not a martinet. He didn’t yell, he didn’t get into faces, he didn’t show players up. If he had thoughts to give it was mano-a-mano rather than a dressing down in front of the entire team. He believed in guiding but not dictating. He let the players find their path.

“We loved to play for Bud because he knew when to work us hard, but let us have fun at the same time,” Paul Krause told The New York Times in 1990.

This is an odd transition because it’s about a martinet. When I was a kid I remember reading a story about a baseball player for the New York Giants who was told by manager John McGraw to bunt but the guy saw a pitch he liked and swung away—and hit a game-winning homerun. His reward? Fined $50 for not following orders. Fran Tarkenton tells a similar story about Bud Grant here: Charlie West catching a punt on the 4-yard line—a no-no—and going 95 yards for a touchdown and the game. While the place is going crazy, Bud Grant quietly let him know: “Charlie, if you ever do that again, you’ll never play another down for the Minnesota Vikings.” What I like about that? There was no fine. And it wasn’t because West disobeyed a command. It was because he did something fundamentally unsound. And Bud told him so quietly.

He was a bit like Clint Eastwood, wasn’t he? Not just the stoic stare but the way he coached. Let’s be professional, let’s have fun, let’s be done by 5 PM.

He was also a helluva athlete. He played two seasons of professional basketball (Mpls. Lakers), two seasons of professional football (Philadelphia Eages), then something like 10 season of professional football in Canada, before coaching there, and then being coaxed back to the States to coach a moribund NFL franchise in Minnesota. Three years later, they were in the Super Bowl. They went to the Super Bowl three more times on his watch.

Yeah, yeah, I know: 0-4. It’s in the subhed of the Times obit: “…although he lost each time.” Classy, NYT.

He also played baseball. My father says that Bud once said he made more money playing town ball around Minnesota than he did for those two seasons with the Lakers.

Bud retired from coaching in ’83, came back for the ’85 season, finished with a 158-96-5 record. He was elected to the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 1983 and the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1994.

Seriously, who was more Minnesotan? When he wasn’t hanging out in shirtsleeves in -6 weather, he was sitting in a duck blind in the snow, or out on a lake, fishing. Godspeed. Raise a glass. Skol.

Wednesday December 21, 2022

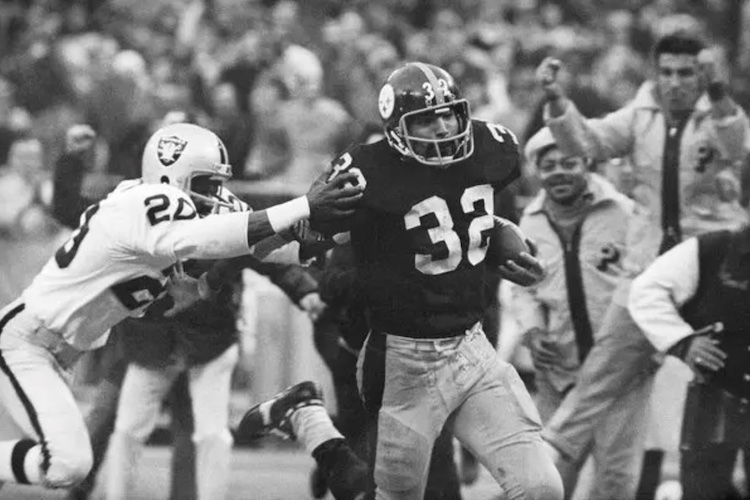

Franco Harris (1950-2022)

The Raiders, the announcers, everybody thought it was over.

It must've been the spring of 1973—in my memory there are mounds of crusty, dirty snow along the periphery of everything—but maybe it was the next fall or the next winter. I guess fall makes more sense because isn't that when they begin selling football cards? The point is, my friend Dave Budge and I were kids hanging around the 54th and Lyndale area in South Minneapolis. There were two main stopoffs in this little enclave, Rexall Drugs, which we called Salk's, and Little General, and each had their appeal. Salk's was a little more adult and sedate, while Little General had a parking lot and felt more dangerous. The bad kids hung out there. Little General was the B movie, basically, and Dave and I were in the Little General parking lot thumbing through the football packs we'd just bought, probably concentrating, a stick of gum hanging out of our mouths, when Dave began to shout.

He got Franco Harris!

And we began to cheer and exalt. We jumped into each other's arms. I remember we were being watched by an amused adult woman, but I didn't care. It was Franco Harris. I don't remember ever being so excited about one of us getting a trading card—baseball, football, Wacky Packages, any of it.

This was after the Immaculate Reception, of course, but Franco was a big story even before then. He was a rookie in 1972 and rushed for over 1,000 yards, back when that was the touchstone, and he had the best RB yards-per-attempt in the NFL: 5.6. I'm looking at the '72 NFL leaders and I guess it was an odd time. The names among the quarterbacks, for example, feel like they have at least one foot set firmly in the past: Billy Kilmer, Earl Morrall, John Hadl. They're doughy white guys. I think '72 was my first year of watching football, and my team, the Vikings, went 7-7, and in the other league the Miami Dolphins couldn't lose, they went 14-0. But there was this upstart team, the Steelers, that was fun, with its rookie running back, and his legion of fans who called themselves “Franco's Army.” I also remember I heard his name wrong at first. I thought he was Frank O'Harris. You know, nice Irish kid. These were the days when, even if you saw a game, you didn't necessarily see it clearly on your little black and white TV. We also had a color TV in the living room, and I believe that's where I was watching the game, the Steelers vs. the Raiders in the divisional round, Dec. 23, 1972, the battle to see who would get to lose to the Dolphins. And I was so, so rooting for the Steelers. I hated the Raiders. I have no idea why. Something about their vibe.

I'd forgotten it was such a low-scoring game: 0-0 at half, 3-0 until the 4th quarter. You can see the stats of the game at Football Reference but the Football Reference site isn't like the Baseball Reference site. Baseball has practically every pitch. Football, you don't even get times of scores.

“60 yard pass from Terry Bradshaw.” I love that. Great job, Bradshaw!

The Stabler run? Apparently that happened with less than two minutes in the game, and the George Blanda extra point seemed to seal the deal. (Talk about players with a foot set firmly in the past: Blanda was 45 at the time.) You can see the catch on YouTube, original broadcast, not-bad quality. That's my memory of it. That camera angle. I'd forgotten the specifics—4th and 10 at their own 40, 20 or so seconds remaining—I just remember how it went from hopelessness to miraculous, from depression to absolute elation, how the camera didn't even pick up the moment, it happened out of camera range, because it was over, so over. And then it wasn't. And then it was the Player of the Moment being in the exact right spot and paying absolute attention. I like how much the Raiders players are caught off guard. They're flat-footed. That's how he scores. They're done and he's still playing.

I also remember it wasn't immediate, that it took a while for the refs to agree that he'd caught the ball, that it was in fact a touchdown. Afterwards, apparently, like a forerunner to Trump, Raiders owner Al Davis stormed around the press box “screaming at league officials that the play was illegal.” (Maybe Davis was why I didn't like the Raiders.) I think one of the things the announcers were mulling over was “Did any Steeler touch the ball before Franco Harris?” If they had, apparently, it was a dead ball. Instead, it was what it was: miraculous. Has any athlete, who was our new player of the moment, ever made a bigger play? There's Willie Mays in '54, and others I'm sure, but Franco in '72 has to be near the top. It was the guy we were all talking about making the postseason play we're still talking about.

He became a Pro Bowler nine times, a Super Bowl champ four times. When he retired in 1984, he was third all-time in rushing yards, behind only Walter Payton and Jim Brown, with 12,120. Here's his Times obit. He was 72.

Sunday October 23, 2022

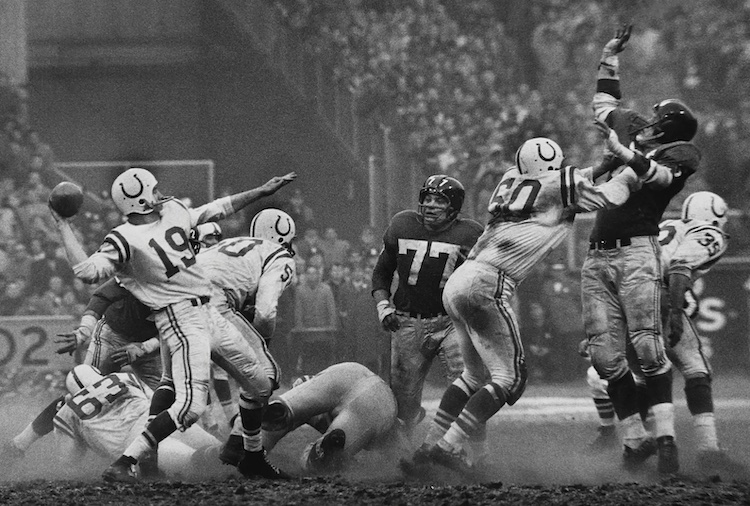

Famous Last Words: Walter Kiesling

“He'll never become anything.”

-- 1950s Pittsburgh Steelers coach Walter Kiesling about the young, third-string quarterback he'd recently cut from the team—a guy named Johnny Unitas. Per Joe Posnanski's countdown of the 101 greatest players in NFL history. Unitas, befitting his jersey number, comes in at #19.

Why did Kiesling feel this way? Apparently he liked running up the middle. This Unitas kid was supposedly a hot-shot passer and he saw no point in that. He also didn't seem to see much point in winning. During his three years with the Steelers, the team never had a winning record, nor finished higher than fourth of six. Posnanski adds a footnote about the general ineptitude of the Steelers of that era: “In a short span, the Steelers passed on Johnny Unitas, Lenny Moore and Jim Brown, and they drafted but released Len Dawson. That's impressive.”

Saturday May 14, 2022

Sid Gillman and Me

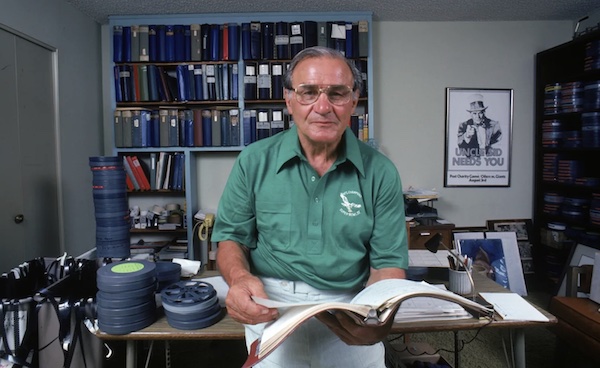

Sid Gillman in 1981

Joe Posnanski is counting down his top 101 football players—to go along with his top 100 baseball players—and two months ago he landed on his No. 46 pick, Lance Alworth, who should be there for his name alone but of course has some pretty impressive stats. His career was ending about the time I began to watch the NFL, but I remember the reverence with which he was spoken.

Some of Poz's piece talks up Alworth's Chargers coach, Sid Gillman, who remade the NFL by focusing on the passing game. He was also one of the first coaches to buy his own movie projector (for $15) and use it to watch football film; to figure out what should and shouldn't be done. Poz adds this story:

In 1991, when Sports Illustrated's Paul Zimmermann went to see the master, he found Gillman in a dark room watching film, even though he was 80 and no longer coaching.

“Sometimes,” Gillman said, “I think, Why am I doing this? I'm almost 80 years old. Why am I evaluating these quarterbacks?” And then, after letting the thought sink in, he would say, “Well, why not? What else would I be doing?”

I was never a football player and stopped watching the NFL seriously after 1980, so it's odd seeing a sliver of myself in such a legend—a coach who reinvented the most popular sport in America. But there I am. Why am I doing this? I'm almost 60 years old ... Well, why not? What else would I be doing? That's probably most of us at the end of the day.

Wednesday September 15, 2021

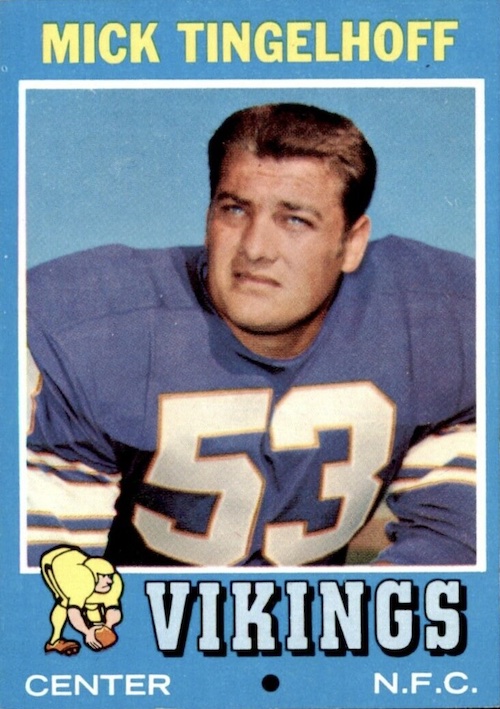

Mick Tingelhoff (1940-2021)

It was a name I heard all the time from about ages 9 to 15, one of many monumental Minnesota sports names from that period—names you could see chiseled in granite: Killebrew, Tarkenton, Goldsworthy, Hilgenberg, Tingelhoff. We don't get names like that anymore, do we? As Harmon was the only Killebrew in MLB history, Mick was the only Tingelhoff in NFL history. They were singular men.

From the Star-Tribune obit:

From the Star-Tribune obit:

Tingelhoff came to the Vikings as an undrafted free agent linebacker from Nebraska in 1962, the Vikings' second season. He shifted to center in the second preseason game, and never missed a regular-season or postseason game over the next 17 seasons. His 240 consecutive starts are a record for an NFL center and second in Vikings' history behind only [Jim] Marshall's 270.

Think about that for a second. He was basically unwanted, had to pivot from his original position, but kept showing up for work. And Vikings history, Star-Trib? Think bigger: NFL history. The only player who has passed Marshall and Tingelhoff for consecutive NFL starts is Green Bay's Brett Favre. Crazier still? Alan Page is still tied for seventh on this list, and—excluding Marshall and Tingelhoff—the others above him all came afterwards. Meaning, for a time, the top three players with the most consecutive NFL starts were all 1960s-70s Minnesota Vikings. Maybe there's something to what Rhoda said: “Eventually I moved to Minneapolis, where it's cold and I figured I'd kept better.” They kept better.

Or were they just tougher? Tingelhoff still holds the consecutive game streak for offensive linemen. Second is Will Shields of KC at 223, a season away, and only one other guy has more than 200. And none of them are centers.

Tingelhoff didn't just show up, didn't just last, he excelled: six-time Pro Bowler, five-time All Pro, co-captain of those great Vikings teams with Jim Marshall. He was the introvert to Marshall's extrovert. Apparently at 6'2“, 237, he was undersized for a lineman, but he was tough. Football Reference has something called AV, Approximate Value, which is its attempt at WAR, and Tingelhoff had the highest AV rating on the 1966 Minnesota Vikings—as a center!—and the sixth-highest overall in Vikings history. His number 53 is one of five numbers retired by the Vikings. (Not sure why they're waiting on Carl Eller.) He entered the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2015—the ninth center to receive the honor. ”Mick Tingelhoff wasn't a Minnesota Viking,“ Fran Tarkenton said as his HOF presenter. ”Mick Tingelhoff is the Minnesota Viking.“

Tough, durable, monumental, Tingelhoff died this week at age 81 ”after a lengthy battle with Alzheimer's,“ according to the STrib. Such sadness in those words. One wonders if it wasn't football related. The New York Times has it slightly different: ”The cause was Parkinson's disease with dementia." But the same question arises. For now, chisel his name in granite.

Thursday September 24, 2020

Gale Sayers (1943-2020)

A couple of times a year I'll think the following:

The Lord is first

My friends are second

And I am third

That's a quote from the back cover of the dog-eared autobiography of Gale Sayers, “I Am Third,” that my older brother owned. I was a huge fan of baseball biographies but I never got into this one for some reason. I don't know if I finished it. But I always liked the title. And though I'm basically agnostic I always liked the sentiment.

My older brother did a good imitation of Sayers, too. OK, not Sayers. Billy Dee Williams as Sayers in the TV movie “Brian's Song,” which was based on some portion of “I Am Third.” Every boy I knew saw that movie. Every boy I knew cried at that movie. Whenever some kid claimed he never cried, that's the thing you'd bring up.

“Never? Not even at 'Brian's Song'?”

“OK...”

I certainly cried at “Brian's Song.” The theme song alone could make me tear up. But the scene that killed me was when Billy Dee as Sayers breaks down in the locker room talking about his friend Brian Piccolo, who had been diagnosed with cancer. One of the lines in that speech is the line my brother spoke when imitating Billy Dee/Sayers: “Brian Piccolo is sick, very sick.” I think about that line a couple of times a year, too.

Gale Sayers and Brian Piccolo became roommates and friends at a time of civil rights and civil strife, so it was a story, a news story, before it ever became a memoir and a TV-movie. They were roommates and numerically adjacent—Sayers #40, Piccolo #41—but opposites every other way. White, black. Brash, shy. Journeyman, superstar. Who couldn't write that story? And then the tragedy. Brian Piccolo was 26 years old when he died of cancer in 1970. Gale Sayers was 77 when he died yesterday of complications from dementia and Alzheimer's. That's a whole other tragedy, and probably football-related. He was diagnosed with it in 2013. Imagine if it were you. A doctor saying you will lose your mind before you lose your life. You will lose your self. Everything you think is you. But you'll still be there.

When I was a kid, Gale Sayers was the standard. I came in at that time. Jim Brown had already been making movies for six years when I began to pay attention to the NFL, and I thought of him the way I thought of someone like Y.A. Tittle: Someone from the dark ages: BSB—Before Super Bowl. But if you look at the numbers it's not even close. Brown dominated for a decade and then left on top with the most rushing yards ever, while Sayers dominated for four years basically and was gone. But he was beautiful in a way few football players ever were. He was already a college legend when he arrived in the NFL in 1965—the Kansas Comet—and he quickly became a football legend. “Give me 18 inches of daylight, that's all I need,” he was famous for saying, and he wasn't wrong. In his rookie season, in the mud of Chicago, he scored six touchdowns against the San Francisco 49ers in a 61-20 romp; nobody's done that since. The next season, he led the league in rushing yards and yards per game. Then he got injured. Knee. But he came back in 1969 and led the league in yards and yards per game. Then he injured the other knee and that was that. To be honest, I don't think I ever saw him play live. I saw him on “NFL Films” and on “Brian's Song.” My father repeated his name with reverence. He did an intake of breath and shook his head sadly and reverentially.

In his tribute, Joe Posnanski compares Sayers to Clemente in terms of beauty and impact, and it's not a bad comparison. Except Clemente actually had a full career; he played 18 seasons. Poz also suggests Sandy Koufax, another comet streaking across the sky, someone who blazed for a glorious moment and was gone. Again: not bad. Let me add another: Tony Oliva: showed up in the mid-60s and dominated: two batting titles in his first two years, a beautiful swing, a gorgeous player. Then knee troubles. Then another batting title. Then more knee troubles. Sayers showed up after Tony-O and left before him because football is that much more brutal, but he also got in the Hall almost immediately. Baseball's Hall still hasn't let Tony in. Maybe because he never quite had that cache. Or maybe because football knows its careers are short and brutish, and so, more than baseball, they appreciate the clean, clear leap of the salmon that has disappeared.

Monday April 06, 2020

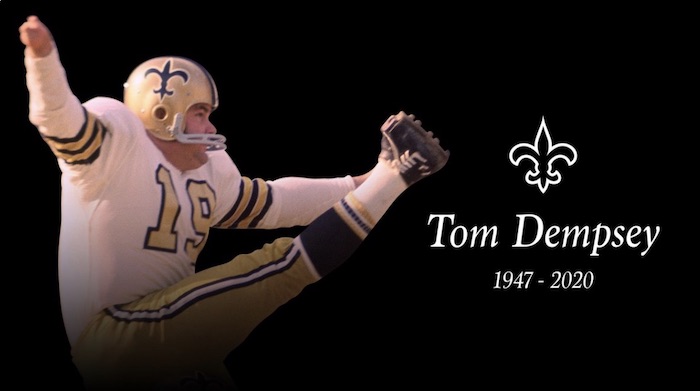

Tom Dempsey (1947-2020)

It feels like I‘ve always known Tom Dempsey’s name. I became a football fan in 1972, at age 9, when his 63-yard field goal for the New Orleans Saints to beat the Detroit Lions 19-17 two years earlier was already the stuff of legend. As was he. He had half a foot. That's what we were always told. Some part of me thought it was chopped off, like Kunta Kinte‘s, but he’d been born that way, without toes or fingers on his right side.

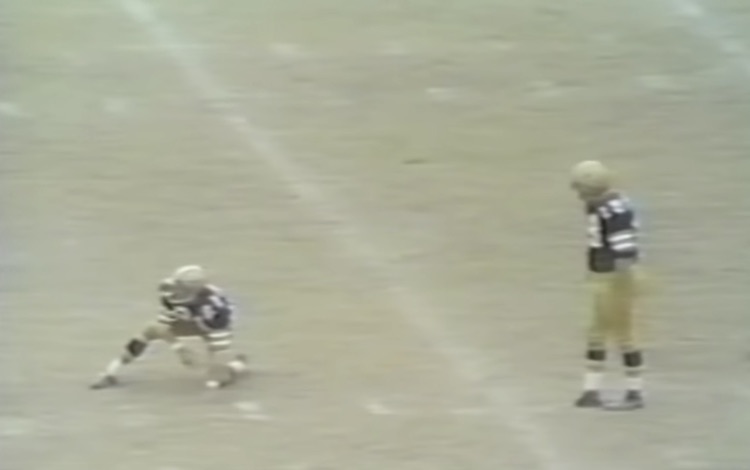

It was particularly the stuff of legend because I never got the chance to see it. You'd watch highlights on “NFL Films” Saturday afternoons, but it was recent stuff, not two-year-old stuff—at least not when I was watching. Or it'd be about winning teams, not the New Orleans Saints, for god's sake. I actually didn't see the kick until about two years ago when someone posted a video on Twitter. Check it out—it's astonishing. Like the Minnesota Vikings' Fred Cox, Dempsey was one of the last of the straight-on kickers, so it was just a couple steps back, head down, boom. Look at the distance traveled. The athletic way that field-goal kickers kick today, using their entire body, was known as “soccer-style” back then. It was the new wave. Cox and Dempsey were the old guys.

Back then, a 45-yard field goal was a nail-biter and anything over 50 was a big ask. Even Dempsey. In his first season, 1969, he tried 11 field goals from 50+ yards and made one. The year he did it, 1970, he was 3 for 9 from that distance. Career: 12 of 39. Even for Dempsey it was basically a 30% shot.

So 63 yards? Add on his handicap and it was a great story.

Some complained his half foot, and the special shoe that went with it, wasn't a handicap so much as a cheat. It gave him an unfair advantage. From the Washington Post's obit:

Tex Schramm, a Dallas Cowboys executive and chairman of the NFL's competition committee, compared Dempsey's shoe to “the head of a golf club with a sledgehammer surface,” and in 1977 the NFL passed “the Dempsey rule,” which required kickers' shoes to have a kicking surface that conforms to that of a normal kicking shoe. It was a rule that offended Dempsey.

“The owners make the rules,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2010, “and my favorite saying about owners is, ‘If you threw them a jockstrap, they’d put it on as a nose guard.' They don't know a damn thing about football.”

The Post adds that recently “ESPN Sport Science analyzed the kick and determined that the shoe, now on display in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, actually was a disadvantage for Dempsey.”

Effin' Cowboys. Always screw shit up.

But this is how big and legendary that kick was. Dempsey broke the previous record (Bert Rechichar, Colts, 1953, 56 yards) by seven yards, which is like a Bob Beamon leap in excellence. No one even tied Dempsey's mark until 1998 (Jason Elam) and no one broke it until 2013 (Matt Prater). It took nearly a half-century—and they did it by just one yard. Is Prater legendary now? I don't know. I'm not a football fan or a kid anymore. I just know the place Dempsey had for us.

He had the longest NFL field goal three years in a row (1969-1971), and in 1971, now with Philadelphia, he led the league in field goal percentage (70.6%), but he was an All-Pro only once (1969) and he isn't in the Hall. The soccer-style guys took over. His last year in the NFL was in 1979, with Buffalo.

He retired with his wife, a school teacher, to a suburb of New Orleans, but the 21st century wasn't kind. First, came Hurricane Katrina, which flooded their home. Wiki has a quote from Dempsey, saying it “flooded me out of a lot of memorabilia, but it can't flood out the memories.” Then life took the memories: Alzheimer's and dementia. He was moved to a nursing home. This year, COVID-19 swept through the nursing home and he contracted it. He died this weekend.

Godspeed.

The moment before the moment.

Saturday April 04, 2020

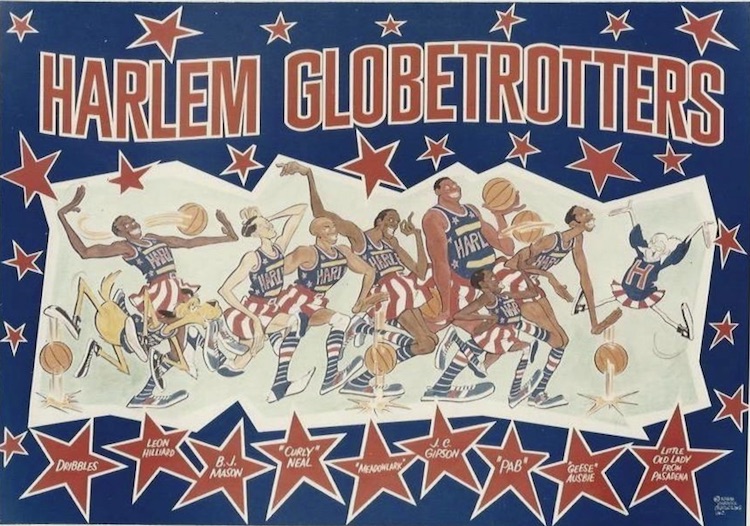

Curly Neal (1942-2020)

How much of a superhero was Curly Neal when I was growing up? The first time I saw him live—the only time I saw him live—when he and the other Harlem Globetrotters played at Met Center in Bloomington, Minn. in the early 1970s, he made that insane half-court shot of his from the corner (an example here, at 16 seconds in) ... and I was a little disappointed. I wasn't disappointed by that; I was disappointed that he didn't juggle like five basketballs perpetually through the hoop as he did in the Saturday morning cartoon show that my brother and I watched regularly—causing the scoreboard to literally blow up. I was disappointed because Curly Neal was not quite a superhero.

Was he my favorite? There was six in the cartoon and they each had bits:

- Meadowlark, the often-hapless leader

- Curly, the right-hand man and ... most athletic? I think he spins the ball on his finger more than anybody; also off his bald pate

- J.C. (J.C. Gipson), a gentle giant, who often scores baskets from balls that bounce off his stomach

- Geese (Hubert Ausbie), goofy

- Pablo (Pablo Robertson), short, perpetually dribbling

- Bobby Joe (Bobby Joe Mason), forgetful

Plus an old white lady (Grannie) and a yellow dog (Dribbles).

Curly was viewed as the great ball-handler on the team until Marques Haynes (“to show you how”) returned for the live-action Saturday morning show “The Harlem Globetrotters Popcorn Machine” in 1974. That's actually Curly's first IMDb credit since they didn't voice themselves in the 1970-72 cartoon. Meadowlark was Scatman Crothers, for example, while Curly was voiced by Stu Gilliam, a standup comedian. But the show was still groundbreaking—the first Saturday-morning cartoon show with a mostly black cast. (“Fat Albert” debuted two years later.) It was also my intro to basketball since Minnesota didn't have a team—we lost the Lakers to a city without lakes in 1960—so there was no local impetus to watch games. The first b-ball game I saw live was probably the Globetrotters at Met Center. They won.

When did it become too much? When they hung out with Scooby Doo? When they showed up on “Donnie and Marie,” “The Golden Hawn Special,” “The Love Boat”? Probably when they got title cred by visiting Gilligan's Island in 1981. That's part of the TV globe they probably shouldn't have trotted to. And with Meadowlark pursuing a solo career, Curly was left to be nominal leader. I think? I never saw the movie. I was a senior in high school by then.

Curly was born Fred Neal in Greensboro, North Carolina, birthplace of the sit-in portion of the civil rights movement in February 1960. By that time, Curly was playing at Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, where, according to Wiki, “he averaged 23.1 points a game and was named All-Central Intercollegiate Athletic Association (CIAA) guard.” He wanted to go to the NBA but wasn't drafted. The Globetrotters was his back-up plan. His back-up plan made him a legend.

“I got a questionnaire letter, as a free agent,” he told The New York Times in 1983. “I would have to pay my way to [an NBA] camp. The Globetrotters sent me a plane ticket and gave me room and board.”

That Times article mentions the wear and tear of the years. It mentions a heart attack he had in Oct. 1971 at the age of 29. That sent him back to college to get his degree. In 2008, he was the fifth Trotter to have his number retired—after Wilt Chamberlain, “Goose” Tatum, Marques Haynes and Meadowlark. Not sure why it took so long.

Has anyone seen the 2005 documentary on the Globetrotters? Or the 1951 movie? I have the 1970 George Vecsey bio paperback of the team but I wouldn't exactly call it all-encompassing. Attention must be paid.

Steve Kerr, coach of the Golden State Warriors, tweeted the best epitaph of all: “Hard to express how much joy Curly Neal brought to my life growing up.” Amen.

Saturday February 22, 2020

‘You Were Meant to Be Here’

“Later, at the news conference, while the young players giggled like schoolboys, they told how Brooks had said before the game, ‘You were meant to be here.’

”Quite dramatic, I thought. When the conference ended, I collared Brooks. ‘Herb, did you really say that?’

“He reached into his jacket breast pocket and pulled out a card. Scrawled on it were the words, You were meant to be here.”

— Gerald Eskenazi, New York Times sports reporter, recalling the “Miracle on Ice” U.S. victory over the Soviet Union, 4-3, in Lake Placid, NY, 40 years ago today.

Monday May 27, 2019

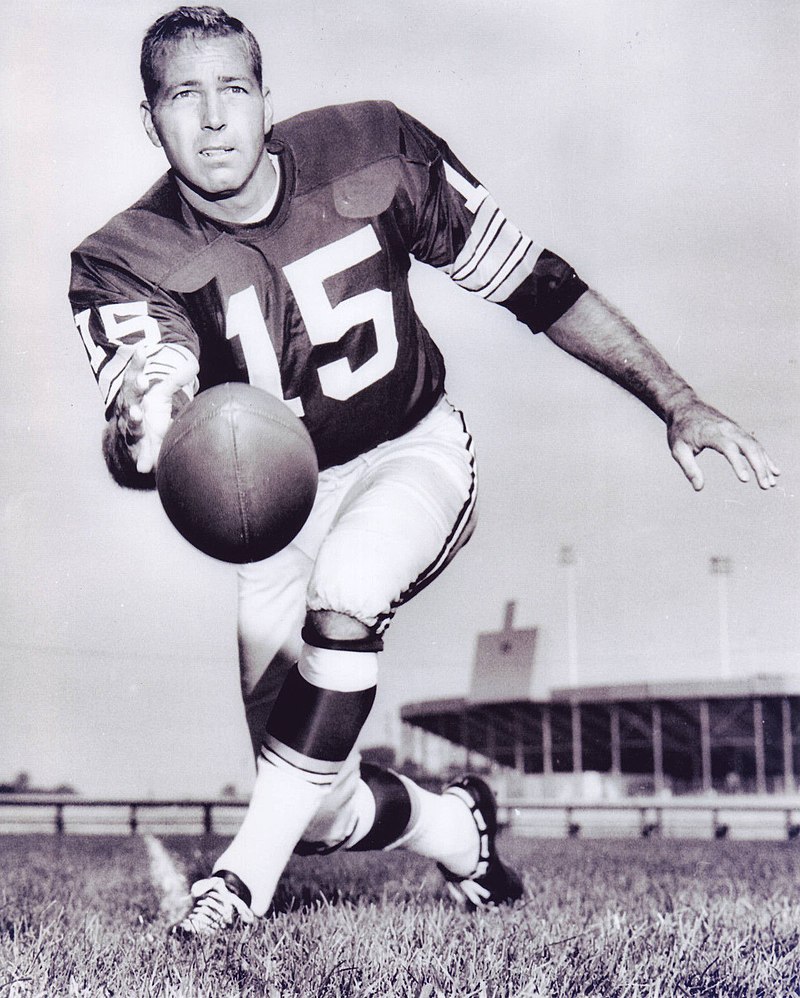

Bart Starr (1934-2019)

I think of Dave Budge, one of my best friends in childhood, who lived across the street in South Minneapolis, and with whom I would throw a football around on Emerson Avenue in spring, fall and sometimes winter.

For some reason (relatives?), he rooted for the Green Bay Packers rather than the Minnesota Vikings, as was custom in our neighborhood.  By this point, the the point I began to care about football, Super Bowls still numbered in single digits (or, I guess more appropriately, before “X”), and the glory days of the Packers were already over. But the team was already legendary. Back then, a lot of teams were 1-1 in the Super Bowl, seeming to lose their first shot only to win a later one:

By this point, the the point I began to care about football, Super Bowls still numbered in single digits (or, I guess more appropriately, before “X”), and the glory days of the Packers were already over. But the team was already legendary. Back then, a lot of teams were 1-1 in the Super Bowl, seeming to lose their first shot only to win a later one:

- Chiefs lost I, won IV

- Colts lost III, won V

- Cowboys lost V, won VI

- Dolphins lost VI, won VII

It was nice—like teams were taking turns. (Until it was the Vikings' turn.) But at the top, both chronologically and in the SB standings, was Vince Lombardi's Green Bay Packers, 2-0 in Super Bowls I and II, and led by #15, the MVP of both Super Bowls, the perfectly named Bart Starr.

Despite that name, he had an ordinary face and manner, and never acted the star. He was thoroughly Midwest in that regard, even though he was Alabama born and bred. He was also at the helm during the legendary “Ice Bowl” victory over the Cowboys in 13-below weather in Green Bay on Dec. 31, 1967. Apparently he was the one who called the QB sneak with the Packers on the Cowboys' goal line, down by 3, with less than 20 seconds left and no timeouts. If it didn't work, season over. But it worked. I remember reading about it and thinking, “I wouldn't have taken that risk.” That he did is why he was where he was.

Did we argue, Dave and I, over who was better, Fran Tarkenton or Bart Starr? Probably. Probably one of the many such arguments as we tossed a non-official football around the neighborhood.

Anyway, when I heard the news, I thought of Dave.

Thursday January 17, 2019

Roughing the Ref

The other day, Joe Posnanski mentioned something in passing—an “outtake,” in his words—during an extensive post on why Aaron Nola's 2018 stats are so incredibly good by certain statistical measures, and whether those measure are wrong or Nola's really that good (spoiler: the measures are wrong).

What he mentioned in passing was about reffing in the NFL:

The referees immediately called it an incomplete pass [in the Philly-Chicago playoff game two weeks ago] because it's not humanly possible to officiate an NFL game. I don't mean this facetiously. It is not humanly possible to officiate an NFL game. The game moves too fast, there's too much happening at once, the rules are too vague and teams work harder at breaking the rules than referees could ever work at upholding them.

Calling an NFL game is like trying to police a 42.4 mph speed limit (or maybe it's 37.3 mph speed limit) on the Autobahn if the cars were (only in specific ways) allowed to crash into each other.

Watching a different game that weekend (Seahawks vs. Cowboys), I had the exact some thought.

It was the 4th quarter, Seahawks were still down by 3, and they had the ball on their own 20 with 9:33 to go. So here we go! First pass from scrimmage, gain of six. No, wait. Penalty on us: holding. Now it's first and 20 at the 10.

So here we go! Another short pass, five yards. No, wait. Penalty on us: unncessary roughness. Now it's second and 22 at the 8.

All of that kind of killed that drive. We wound up punting, they wound up scoring (to go ahead by 10), we wound up scoring (to bring it within 2), but then flubbed the onside kick and that was the game and the season.

I‘ve spent a lifetime listening to my father yelling at the refs on Sunday afternoons in Minnesota, and I kind of did the same during that drive at a Seattle bar, but it also made me think. How many refs are there on the field? Seven? How many umps during a MLB game? Four? Six during the postseason? But think of the difference in responsibilities. In baseball, the job is basically to follow the ball. That’s really it. If a player leads off an inning with a single to right, umps won't have to look at the center-fielder or left-fielder or third baseman or shortstop; they won't factor. Just follow the ball and follow the runner.

In football, refs have to watch every single player on every single play. Even a guy across the field from where the action is. He could do something—flag!—that brings the play back. Imagine if that happened in baseball. “Sorry, Felix, that's not a strikeout; the third baseman did X while you were throwing the ball.”

I don't know how refs do it. I suppose we should stop yelling at them and take in the enormity of the task.

Sunday January 21, 2018

Pick a Pose

A lot has been written about the Minnesota Vikings thrilling, last-minute victory over the New Orleans Saints last Sunday, but I particularly like this piece by Barry Svrluga in The Washington Post. He goes into the background of game-changer Stefon Diggs and the “late-round guys” that make up the Vikings offense. It's classic underdog stuff. Here's the end:

There are paintings of Ahmad Rashad and Jim Marshall and Fran Tarkenton and so many others hung in different spots around U.S. Bank Stadium. Pick a pose for Diggs now — leaping to grab the ball, balancing himself with his hand, spreading his arm as a disbelieving stadium pulsed around him, flinging his helmet in celebration afterward. The kid from Gaithersburg, Md., who felt slighted all this time needs to feel that way no longer. His life changed Sunday night, and he will forever be a hero here.

Monday January 15, 2018

‘This Doesn’t Happen to Us'

“In the moment, when there is ten seconds left, you start preparing your mind with all the past conditioning; you start saying, ‘It doesn’t matter' and ‘We are now free to stop watching and caring’ and then boom Diggs is up in the air, he catches the ball. Does he run out of bounds for the field goal? No, there is no time. Does he step out of bounds? Did one knee touch the surface after the catch? Where's the flag? There has to be a flag that brings it all back? ... This is the life and legacy of being a Vikings fan. It can't be real. This doesn't happen to us.”

— Robb Mitchell, long-suffering Vikings fan, the day after Stefon Diggs' incredible 61-yard touchdown that propeled the Vikings to the NFC Championship.

Sunday January 14, 2018

The Minneapolis Miracle

Stefon Diggs redeems a franchise.

After it was all over, after I'd yelled at the TV about the flag that had flashed across the screen for an instant (an orange peel, we later found out), and after I couldn't believe that Drew Pearson hadn't been called for something (offensive interference, pushing off, being a Dallas Cowboy), and after the Vikings attempted a last-minute drive of their own that went nowhere, and the game, and the season, and the dream died, I put on my coat, hat and gloves, and in the twilight, with snow crunching beneath my feet, walked down 54th to Salk's Rexall Drugs. And there, while I looked at the comic book racks but didn't really look at the comic book racks, I heard a conversation between the back cashier and the pharmacist.

“Vikings lost.”

“Yeah? What happened?”

“Don't know. Just heard they lost.”

Casual, like that. Just another day.

I wanted to yell at them, these strangers, these poor people working the last Sunday of the year, December 29, 1975. Because IT WASN'T CASUAL! It was HORRIBLE! It was THE END OF THE WORLD!

Instead I walked back outside, down Lyndale, and over to 53rd, and made my way home in the cold. I was 12, almost 13. I didn't know about adult solutions to pain yet—drinking, pot, Xanax, whatever. All I had was walking in the Minnesota cold.

I'd been a fan since ‘72, when we went 7-7, and when we still had, I believe, Gary Cuozzo as QB, before we got back Francis, scrambling Fran Tarkenton. The next year we went to the Super Bowl against the Dolphins, and lost, and the year after we went to the Super Bowl against the Steelers, and lost, and the year after the Drew Pearson debacle, the ’76 season, we went to the Super Bowl against the Raiders, and lost. And by the end of the decade I was doing other things and never watched football regularly again. Not like this. Never like this again.

But I have friends in Minnesota who still bleed purple, and for them, and for the 12-year-old in me, the end of today's game, a 61-yard touchdown pass to Stefon Diggs with no time remaining, to beat the New Orleans Saints 29-24, and send the Vikings to the NFC Championship Game against the Eagles, feels fucking awesome. It brings tears to my eyes. I didn't even watch the game but I‘ve seen that final play a dozen times now. I could watch it 100 times.

It was finally the Vikings’ turn. After all that heartbreak, it was finally their time. And your time, Jim, and Adam, and Eric, and Stu, and Deano. And Dad.

Skol.

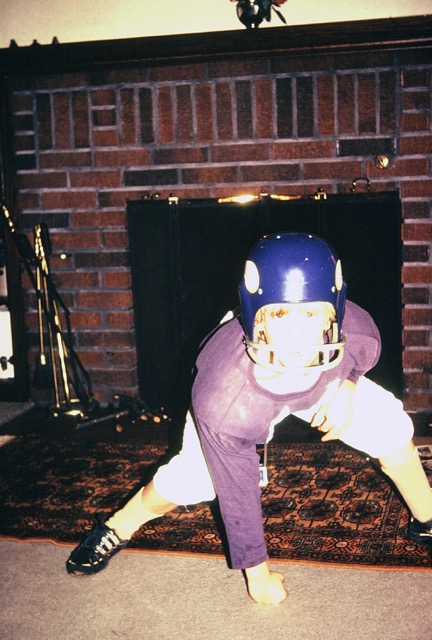

Halloween 1972

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)