Movie Reviews - 2010 posts

Saturday June 23, 2018

Movie Review: Ip Man 2 (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Ip Man 2” has the same basic structure as “Ip Man.” Why not, right? Why mess with success?

For the first hour, the battles for the titular hero (Donnie Yen) are internecine—i.e., among other Chinese. Loudmouths challenge him. Other kung fu schools challenge his. There are hints of corruption among the powerful.

In the second half, the real enemy emerges: a foreigner. In the first movie it was an occupying Japanese general intent on proving the superiority of karate over Chinese kung fu. Here, it’s a huge, brash Brit intent on proving the superiority of western boxing over Chinese kung fu.

The movie also tosses in a bit of “Rocky IV.” You see it coming a mile off. You know exactly how it’s all going to end but it’s still a pleasure getting there.

功夫比拳击好

To be honest, I’ve never really understood the respect Hong Kong movies have given western boxing—as if it were on par with martial arts. Is it grass-is-greener stuff? Is it a century of defeat at the hands of western powers? The size of the combatants? Politeness? I always thought Asian martial arts kicked western boxing’s ass. Maybe that’s my own skewed grass-is-greener perspective. Maybe it’s my wish, as a short man, that something besides brute force wins. Not to mention this: You have a handful of boxing movies in Hollywood but it’s hardly a prospering genre. And in those few boxing movies, you don’t have the hero saving the day outside the ring with their skills. There’s just no comparison.

To be honest, I’ve never really understood the respect Hong Kong movies have given western boxing—as if it were on par with martial arts. Is it grass-is-greener stuff? Is it a century of defeat at the hands of western powers? The size of the combatants? Politeness? I always thought Asian martial arts kicked western boxing’s ass. Maybe that’s my own skewed grass-is-greener perspective. Maybe it’s my wish, as a short man, that something besides brute force wins. Not to mention this: You have a handful of boxing movies in Hollywood but it’s hardly a prospering genre. And in those few boxing movies, you don’t have the hero saving the day outside the ring with their skills. There’s just no comparison.

“2” opens with Ip Man, his young son, and his forever disapproving wife, Wing Sing (Lynn Hung, doomed to be the Adrian in the series), moving from his hometown of Fushun to Hong Kong in 1950. Kan (Ngo Ka-nin), an old Fushun friend, shows him an apartment with a rooftop where he can set up his Martial Arts school. But does anyone want to study? That’s the first dilemma. He draws flyers, puts them up, 没有了. He looks worried. They’re broke. His son asks for student fees but he can’t pay them; when the landlord knocks they pretend not to be home.

Then Wong Leung (Huang Xiaoming, Marco from “Women Who Flirt”), a brash kid, arrives and says he’ll study if Ip Man can beat him. Defeated, Leung flees, then returns with three friends, whom Ip Man takes down without breaking a sweat. He beats them while protecting them. And suddenly he has students. Four becomes 12 becomes 20. First dilemma resolved.

But it leads to the second: Rival schools tear down the Wing Chun posters and insult Ip Man. Students fighting amongst themselves lead to Ip Man taking on 30 of the students, which leads to the reveal of the rival school’s master, Master Hung, played by Hong Kong legend, and this movie’s action choreographer, Sammo Hung. Now Ip Man has to meet the other Hong Kong masters. He has to pass a test: Around a sea of upturned chairs—which used to be knives, we’re told—he has to stand on a wide, round table and take on all comers until an incense stick burns itself out. If he’s so much as knocked off the table, he’s out. Master 1 tries, Master 2 tries. Then it’s Master Hung. They battle to a standstill, but when Ip Man is still too honorable to pay into the club, which he sees as a form of brivergy, e remains unprotected. We get more squabbles. Along the way, Hung develops a quiet respect for Ip Man.

Then the real enemy emerges: Twister (Darren Shahlavi), a western boxing champion, who, at an event to honor him, mocks the display of Chinese martial arts as “dance,” and then beats up all rivals. He stands in the ring, roars like an animal, and insults the Chinese, as Ip Man, stunned, watches from the crowd. You can see where this is going.

Except first we get the “Rocky IV” component: Twister takes on Master Hong and kills him in the ring—the way Ivan Drago killed Apollo Creed. That’s telegraphed a mile away, too.

I was surprised at how worried Ip Man looked before his match—and how beat up he gets. Another “Rocky” element, I suppose. Halfway through the match, he’s suddenly not allowed to use his legs, which seems a cheat; but then, channeling the spirit of Master Hing, he perseveres, saves the honor of China and Chinese martial arts, and gives a ringside speech about the dignity of all peoples. But first he punches Twister’s stupid face in. Because, c’mon, that’s why we came.

下次,李小龙

It works. It’s a good sequel to a good movie. Director Wilson Yip gives us sweeping shots of old Hong Kong and the production values are high. Plus we get a tease for the arrival of Ip Man’s greatest student: Bruce Lee.

Plus: What a calm, pleasant hero. He massages his pregnant wife’s legs and helps his neighbor hang her laundry. When Leung asks him if he can defeat 10 men (which he did in the first film), he simply smiles and says, “It’s better not to fight.” When Leung asks, “What if they have weapons?” Ip Man responds: “Run.”

Again, this may be grass-is-greener, but I could use some Hollywood heroes similarly inclined.

Tuesday February 16, 2016

Movie Review: True Legend (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“True Legend” seems like a typical revenge movie until it isn’t; then it slaps on a half hour coda that points the way toward other, better movies. But there’s a meta aspect I found intriguing.

First the plot, such as it is.

Poor loser

Su Can (Zhao Wenzhuo) is a general in 1860s China that’s overrun by foreigners in the wake of the Unequal Treaties. (Fodder for martial arts movie forever.) In a huge cavern, he almost singlehandedly rescues an imperial prince, then in humble, Buddhist fashion, gives up a governorship to return home to his wife, Yuan Ying (the ridiculously beautiful Zhou Xun), and their son, Feng, and start a Wushu school. It’s an odd move. What’s the point of a Wushu school in a China overrun by wyguoren? He also suggests his godbrother as governor, when everyone can see that Yuan Lie (Andy On) is a haughty, resentful man. But off Su goes. And he prospers.

Then Yuan Lie returns with an army to get his revenge. Why revenge? It turns out he and Ying are adopted siblings of Su’s father, who killed Yuan’s father in a battle long ago. Su’s father raised them, but, you know, blood will out. And he beheads the old man, then takes Ying and Feng next to a roaring river. To throw them in? No. He’s waiting for Su. He's itching for a fight.

Then Yuan Lie returns with an army to get his revenge. Why revenge? It turns out he and Ying are adopted siblings of Su’s father, who killed Yuan’s father in a battle long ago. Su’s father raised them, but, you know, blood will out. And he beheads the old man, then takes Ying and Feng next to a roaring river. To throw them in? No. He’s waiting for Su. He's itching for a fight.

First thought: Su is so much better at gongfu. How can Yuan take him?

Because he’s been cheating. He’s had armor plating stitched into his skin, like the ironclad ships the Ching dynasty couldn’t defeat. He’s also developed the Five Venoms Fist move, which, for our purposes, turn his arms blue and injects venom into his opponents. That’s how he wins. Su, poisoned, falls into the river, and Ying after him, to save him. The boy gets left behind.

Su and Ying are further saved in the mountains by Dr. Yu (special guest star Michelle Yeoh!), but Su, the man who was so magnanimous in victory, is a poor loser. First he starts drinking. Then he starts punching trees and ripping off their bark. Then martial arts masters appear before him tauntingly, always out of reach. The Old Sage (Liu Chia-Hui) says he will teach him, “Only if you defeat the God of Wushu” (Jay Chou). So day after day, week after week, year after year, Su fights the God of Wushu. And guess what? It’s all in his head. It’s like “Fight Club.” Ying tearfully tries to get him to see this, but it’s only after he finally wins that he sees it himself. “Ying is right,” he says, almost cheerfully. “You are all in my head. I never want to see you again, ha ha ha.”

This sets up the final battle with Yuan Lie, who, being the villain, rigs the game. He has his soldiers bury Ying alive. Problem? He neglects to tell Su this; and Su, ripping off Lie’s armor like it’s the bark of a tree, kills him first. By the time Su finds his wife, it’s too late.

So at this point, we’re 75 minutes in. Our villain is dead, our hero’s wife killed. Where does we go from here?

We go to my favorite part of the movie.

The legend who taught the legend

By the way: You thought Su took the first defeat hard? Even though he has a son to raise, Su becomes a town drunk: long matted hair and beard, tattered rags for clothes, forcing his son to beg for money. Ah, but foreigners are still insulting Chinese women and killing Chinese men. So Su, in his drunken craziness, develops the “drunken fist” style of fighting; and in a raised, star-shaped arena surrounded by tigers, he takes on, and defeats, the usual haughty, muscle-bound foreigners, led by 11th-hour villain Anthony, played with scenery-chewing and line-forgetting aplomb by David Carradine, in one of his last film roles. The End.

But that's not my favorite part of the movie. This is: the title card right before the closing credits.

Yeah, that sounds like a dig, but that title card genuinely made the movie for me. Because it reveals—and I probably should have known this going in—that Su becomes Beggar Su, the giggling, red-nosed master who teaches the drunken fist to the better-known legend, Wong Fei-hung, who’s been portrayed in the movies 100 times—most famously in “Drunken Master,” which made an international star out of Jackie Chan in 1978. More, not only does that movie and this one share directors (famed fight choreographer Yuen Woo-ping), but it was Woo-ping’s father, Yuen Siu-Tin, who originally played Beggar Su back in ’78, just a year before his death. So “True Legend” is like Woo-ping resurrecting his own father.

How cool is that?

I just wish I found the movie itself as fascinating.

Zhou Xun: The other reason to see the movie.

Friday July 18, 2014

Movie Review: A Somewhat Gentle Man (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I checked this out because I was so impressed with the later Hans Petter Moland/ Stellan Skarsgård collaboration, “Kraftidioten,” but “A Somewhat Gentle Man” (Norwegian: “En ganske snill mann”) didn’t quite work for me. Despite its great title, the dark humor is slightly off, its secondary characters aren’t as memorable, and then there’s the ick factor.

The ick, by the way, isn’t about violence; it’s about sex.

Skarsgård is excellent as Ulrik, a pony-tailed mob enforcer who, as the movie opens, is being released from prison after 12 years. A friendly guard offers him a bottle of booze and a piece of advice: Keep moving forward; don’t look back. So what’s the first thing Ulrik does when he steps out the gates? He looks back.

Not with animosity. If anything Ulrik seems stupefied, and it takes us a while to figure out it’s no pose. He was once a man who could kill without thought, but now he’s a man who doesn’t have many thoughts. Mostly he’s interested in going along to getting along. To a cringe-worthy degree.

Not with animosity. If anything Ulrik seems stupefied, and it takes us a while to figure out it’s no pose. He was once a man who could kill without thought, but now he’s a man who doesn’t have many thoughts. Mostly he’s interested in going along to getting along. To a cringe-worthy degree.

At a café, he meets his old mob boss, Rune Jensen (Bjørn Flobert of “Kitchen Stories”), and the gum-chewing, matter-of-fact but argumentative assistant Rolf (Gard B. Eidsvold), and the former sets him up with a place to live, a job, and an assignment. The place to live is with Rune’s sister, Karen Margrethe (Jorunn Kjellsby), an ugly, unpleasant woman who sticks Ulrik in the prison-like surroundings of her basement. The job is at an automechanic’s garage, run by Sven (Bjørn Sundquist), who talks out subjects in long run-on sentences, and who warns Ulrik away from his secretary, Merete (Janikke Kruse), a pretty but severe woman. And the assignment is to kill the guy who sent Ulrik to jail 12 years ago.

So what happens? He winds up rejecting the assignment but sleeping with the woman. Not Merete; Karen Margrethe. That’s the ick factor. Imagine Billy Crystal sleeping with Anne Ramsey in “Throw Momma from the Train” and you get an inkling. Then times it by three.

First, Karen Margrethe brings him a television set, which he adjusts to get a Polish station; then crappy dinner leftovers; then increasingly elaborate dinners as her interest is piqued by his lack of interest. Finally, she steps out of her voluminous underwear and lays down on the small bed where he’s watching TV and tells him to get on. He does so dutifully. Not many movie scenes are tougher to watch.

Then it happens again. And again. Each time, you’re waving your hands in surrender: “No ... no!”

The world—and other women—act upon Ulrik as well. Merete’s former husband shows up at the garage and acts like an asshole; Ulrik watches. Ulrik’s ex-wife (Kjersti Holmen) tells him his son has disowned him, then asks for a quickie; he obliges. The son, Geir (Jan Gunnar Røise), finally meets the father, but without emotion, and introduces him as his uncle to his pregnant wife; Ulrik nods and goes along with it. Meanwhile, whenever he takes out a cigarette he’s told he can’t smoke there.

But slowly he begins to break out of his spiritual prison. Sven has a heart attack and asks Ulrik to watch the garage, where the ex-hubby shows up and beats on Merete until Ulrik headbutts him, takes him outside, warns him against hitting women and children, then breaks both arms. Merete is slowly grateful and, in passive-aggressive fashion, seduces him. But Karen Margrethe suspects, gets jealous, rats him out. All the small things Ulrik had slowly built up crumble, so he agrees to take back the assignment to kill the man who sent him to prison. But will he go through with it? Can he still kill without thought? Without conscience?

The ending is nice—standing outside at the salvage yard, enjoying a smoke, talking up the coming spring—and, again, Skarsgård is perfect in the role. You buy him as both acted upon and actor; as stupefied and smart. But the tone of the humor is either too loud (Sven’s run-on sentences) or too soft (the no-smoking bits). A few years later, with “Kraftidioten,” Moland gets the tone perfect.

Wednesday November 14, 2012

Movie Review: 30 for 30: The House of Steinbrenner (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Anyone who knows me knows I’m no fan of the New York Yankees; but even they, the team named after a masturbatory gesture, that added “Suck” to the baseball lexicon, those overpaying, playing-field-tilting, star-grabbing 1% bastards of Major League Baseball, even they deserve a better documentary than this.

It’s a muddled movie. It was filmed in 2008, when the Yankees played their last game at Yankee Stadium, and in 2009, when they moved to New Yankee Stadium and won their 27th World Series title, and in 2010, when George Steinbrenner, the owner of the club since 1973, the Mouth that Roared, finally died after a long illness; and during these years the team is at a kind of crossroads. Is New Yankee Stadium for fans or corporations? Will the winning tradition continue? The old is dying and the new cannot yet be born, and in this interregnum Barbara Kopple filmed “The House of Steinbrenner.”

It doesn’t help that Kopple, a two-time Academy Award winner for “Harlan County U.S.A.” (1976) and “American Dream” (1990), is a Yankees fan. ESPN’s 30-for-30 docs begin with the filmmaker talking about why they were interested in the subject. Here’s Kopple:

When I was a kid I went to Yankee games with my brother and my parents and how could I not want to make a film about the Yankees? I mean, the Yankees are the biggest sports entity in the world. And I think what really made me want to do it is I was home and watching the All-Star Game. And I saw George Steinbrenner going around in a golf cart. He starts to cry. And I just thought, “This could be an amazing film.”

It isn’t. It’s tough to tell the story of something you love. Love is about not seeing clearly. That’s its point.

It isn’t. It’s tough to tell the story of something you love. Love is about not seeing clearly. That’s its point.

The stupid shit Yankee fans say

“The House of Steinbrenner” begins in triumph with the Yankees’ 27th World Series title and a ticker-tape parade through Manhattan. We get shots of the Yankees on their floats: Nick Swisher rocking out like a rock star, Alex Rodriguez, as always, too self-aware, Derek Jeter looking up at buildings as if he’d never seen them. We get sound-bite interviews with fans whooping it up and saying the stupid shit Yankee fans say:

- “The world is back to normal. Because the Yankees are champions of the World Series!”

- “The Steinbrenner family is the greatest owners in sports! New York fans are the luckiest cause they’ve got the Steinbrenners, who spend money so we can have parades like this! Let’s do it again!”

Then we get the sadness and nostalgia of the last game at Yankee Stadium, the House that Ruth Built, and the excitement and disappointment (expensive seats; obstructed views) of the first day at New Yankee Stadium. We get a lot about George but little from George, since, by this time, the illness that would take his life in 2010 had rendered him mute. We get a really nice line from one of the New York scribes:

He’s not George anymore. He’s a quiet man in his twilight and looks at the scene from afar now.

Meanwhile, Hal Steinbrenner, heir apparent, comes off as a tight-lipped, bristly CEO. He comes off as a numbers man. He’s someone desperate to make sure the mask doesn’t slip.

Fudging Yankee history

It doesn’t help that the doc fudges Yankees history. Early on, Kopple asks various folks, “What’s your favorite memory at Yankee Stadium?” and we hear three answers:

- Louis Requena, official photographer at Yankee Stadium, says, “Maris hitting that big homerun. You know?”

- Yogi Berra, catcher and philosopher, says, “I gotta say the no-hitter. That Don Larsen pitched.”

- George Steinbrenner, circa 1998, says: “’77/’78, great teams. I can remember plays. I remember Piniella’s play in right field, one of the greatest defensive plays I’ve ever seen. Couldn’t see the ball. Stuck his glove out—boom. It hit. Against the Red Sox. The playoff.”

What’s wrong with these answers?

Perspective on the Maris homerun would’ve been nice: the fact that Yankee fans spent 1961 booing Maris because he wasn’t Mickey Mantle; the fact that hardly anyone showed up for the last game of the season when he was sitting on 60.

The Yogi thing is simply semantics. I can guarantee you that almost every baseball fan watching muttered underneath his breath, “Perfect game,” every time Berra said “No hitter.”

Then there’s Piniella’s catch. As soon as Steinbrenner mentioned it I saw it in my mind. Bottom of the ninth inning, Sox down 5-4. With one out, Rick Burleson draws a walk. Then Jerry Remy hits a line-drive to right field. What we don’t know is that Piniella has lost the ball in the late-afternoon sun. We don’t know it because he pretends he doesn’t. He pretends he’s about to catch it, and this keeps Burleson close to first. And then Lou’s lucky. The ball drops five feet away from him and he stabs at it with his glove and keeps Burleson from going to third. So it’s first and second, rather than second and third, when Jim Rice flies out to deep right. Burleson can only tag up to third rather than home. He doesn’t tie the game. Then the great Carl Yastrzemski pops up for the final out and the Yankees win and go on to win the ALCS and the World Series—their 22nd.

Except that’s not the highlight they show. The highlight they show is the catch in the bottom of the 6th when, with two on and two out, Piniella went into the corner to rob Fred Lynn of extra bases. It’s a nice catch. But I’ve never heard anyone say Piniella lost that one in the sun. So … did they show the wrong clip? In a documentary called “The House of Steinbrenner,” while relaying George Steinbrenner’s favorite moment at Yankee Stadium, did they show us the wrong moment?

Fudging Steinbrenner

But the history that’s mostly fudged isn’t from Steinbrenner; it’s about Steinbrenner.

Memories are short, the man is dying and then dead, so the encomiums come fast and furious. We get eulogies. Fans remember ’77 and ’78, and the late ‘90s dynasty, and forget the years in the wilderness. They forget that Steinbrenner’s desire to win got in the way of winning. He was too impatient, and, as a result, under his watch, the Yankees went pennant-less (15 years), and without a World Series title (18 years), for longer than at any time since the team bought Babe Ruth in 1919. And, it could be argued, and has been argued, that they only won then, in 1996, because Steinbrenner had been banned from Major League Baseball in 1990 for hiring a private detective to tail his superstar outfielder Dave Winfield. As a result, for two or three years, he wasn’t around to muck up the works. He wasn’t there to trade prospects like Derek Jeter, Mariano Rivera and Andy Pettite for an aging star or utility player. Thus Jeter, Rivera, Pettite stayed. And they became the core of that 1990s dynasty.

The fans blame Hal for the problems of New Yankee Stadium, but that was George’s baby. We get a clip of him in 2002, talking. “You hate to think about moving away from that great stadium,” he says. “But we do have problems: all the new stadiums coming. We have new generations of people coming. That maybe that stadium doesn’t mean as much to them.”

Right. Steinbrenner was more interested in the profits a new stadium and its corporate boxes could bring than in the grand tradition of Yankee Stadium. The Yankee organization put profits before tradition, then went out and bought a bunch of players and won in their first year at the new ballpark. Since? Bupkis.

Is this the new curse? Old Yankee Stadium cursing New Yankee Stadium? Let it be so.

There are people and there are assholes

At least the scribes get George right:

- Bill Gallo of The New York Daily News: “He was vain. He was at times rude. He reminded me of a Prussian general: General von Steinbrenner.”

- Maury Allen of The New York Post: “He thought the loss of a game in June was the end of a season. … He loved the ego gratification of what the Yankees is all about.”

George, too, gets George right. “There are major league ballplayers,” he says, “and there are Yankees.”

Man, that’s an asshole thing to say. “The House of Steinbrenner” is a documentary about such assholes, directed by a woman who loves them so.

Thursday June 21, 2012

Movie Review: Les femmes du 6čme étage (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Is there no culture, no matter how free and sexy it seems to outsiders, who don’t see themselves as uptight and staid and in need of the wildness of another, generally more southern culture?

So as the British did with Italy in E.M. Forster’s novels and subsequent Merchant-Ivory films, and as Americans do in the Caribbean, getting their groove back, etc., so the French, in “The Women on the 6th Floor,” turn to Spain to shake off the shackles of their deadening, monetized, neutered civility. And they don’t even have to leave Paris to do it.

It’s 1962, and Jean-Louis Joubert (Fabrice Luchini) and his wife Suzanne (Sandrine Kiberlain) live in relative luxury in an apartment in Paris. He’s a successful, genial stockbroker, she shops and complains. But right before the movie begins, his mother dies. Apparently she ran the household with the help of a longstanding, dour French maid, Germaine (Michčle Gleizer), who in effect raised their kids, now off at boarding school, and over whatever objections Suzanne had at the time. But: queen is dead, long live the queen. Suzanne and Germaine now clash, Germaine leaves in a huff (or on a bender after some Malaga wine from the Spanish maids on the 6th floor), and in the next shot there are dishes in the sink, the refrigerator is filthy and M. Joubert has no clean shirts. What to do? Mme. Joubert is at a loss. But her pick-a-little, talk-a-little friends suggest the latest thing: a Spanish maid. Apparently Mme. Joubert doesn’t know a whole passel of them live on the 6th floor of her building, so she goes to the local church and picks out Maria Gonzalez (Natalie Verbeke), who 1) lives on the 6th floor, 2) is newly arrived from Spain, and 3) is a looker. Because what wife doesn’t want a hot maid cooking for her husband?

It’s 1962, and Jean-Louis Joubert (Fabrice Luchini) and his wife Suzanne (Sandrine Kiberlain) live in relative luxury in an apartment in Paris. He’s a successful, genial stockbroker, she shops and complains. But right before the movie begins, his mother dies. Apparently she ran the household with the help of a longstanding, dour French maid, Germaine (Michčle Gleizer), who in effect raised their kids, now off at boarding school, and over whatever objections Suzanne had at the time. But: queen is dead, long live the queen. Suzanne and Germaine now clash, Germaine leaves in a huff (or on a bender after some Malaga wine from the Spanish maids on the 6th floor), and in the next shot there are dishes in the sink, the refrigerator is filthy and M. Joubert has no clean shirts. What to do? Mme. Joubert is at a loss. But her pick-a-little, talk-a-little friends suggest the latest thing: a Spanish maid. Apparently Mme. Joubert doesn’t know a whole passel of them live on the 6th floor of her building, so she goes to the local church and picks out Maria Gonzalez (Natalie Verbeke), who 1) lives on the 6th floor, 2) is newly arrived from Spain, and 3) is a looker. Because what wife doesn’t want a hot maid cooking for her husband?

There are trials. Maria must make M. Joubert’s egg just so, three and a half minutes, and does. She is given impossible tasks by the Suzanne ... and enlists the other maids to help complete them. They sing a Spanish version of “Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” while doing so. It looks like fun. Maiding.

The other maids are mostly stock, nondescript, and/or played by Almodovar alums. There’s Maria’s Auntie, Concepcion (Carmen Maura, who’s been in almost every Almodovar since “Folle ... Folle ... folleme Tim!” in 1978, and who picked up a Cesar for her performance here), stocky and jovial; Dolores (Berta Ojea) is also stocky and jovial. There’s Carmen (Lola Dueńas, “Broken Embraces,” “Volver,” “Talk to Her”), a tough, cynical communist, and Teresa (Nuria Solé), a tall drink of water who winds up married to a French salon keeper. Then our Maria of the beautiful eyes.

Initially, Jean-Louis is a bit stodgy, demanding that Maria call him “Sir,” etc., and Maria has secrets, including an 8-year-old son back in Spain, and the maids have various machinations and battles with the nasty concierge, Mme. Triboulet (Annie Mercier).

We get Jean-Louis’ background in a burst while helping Maria move some of Madame’s things to the 6th floor. Apparently his grandfather started the brokerage firm, his father maintained it, and now he runs it. Apparently he’s lived his whole life in this building. Not a surprise. He seems a dull man without much imagination. At this point, for example, he hasn’t imagined sleeping with Maria.

But on the 6th floor he’s introduced to the other maids, helps them with their stopped-up toilet, and basks in their gratitude. He lets Dolores use his phone (landline, kids) to find out about her sister’s child. In this manner he becomes immersed in the lives of the maids and becomes interested in all things Spanish. “You never worry about anybody, suddenly you care about Spanish maids?” his wife asks him. He does. Fairly innocently thus far.

Eventually, despite the above comment, his wife mistakes his absences for an affair with a client, the notorious, red-haired man-eater Bettina de Brossolette (Audrey Fleurot), and she throws him out. After a pause on the steps, he returns to a room on the 6th floor and lives with the maids. He’s never had a room of his own. He luxuriates in it. It’s kind of cute, actually. The man who has much who’s never had this.

If the maids had all been dumpy, and his interest in them quirky, I might have been charmed by “Les femmes du 6čme étage.” But the maids are not all dumpy and his interest in them, at some point, is fired mostly by his interest in Maria, which he hides, poorly, behind an unsure smile and dumbfounded looks. They sleep together, of course. But they’re so nice about it. And that wife is so awful.

That’s the movie, basically: a rich, dumpy Frenchman leaves his wife to fuck his hot Spanish maid. But the movie stacks the decks so we like both of them, don’t like the wife, and get our happy ending in Spain, where Maria flees, despite another child, a daughter this time, but where Jean-Louis finds her hanging up the wash. He smiles at her, she smiles at him. The ending implies they wind up together. But what does she see in him besides money? What does he see in her besides hot? What happens when his money and her looks go? What will they have? Nice? How long before she throws that three-and-a-half minute egg in his face?

Friday April 13, 2012

Movie Review: Clash of the Titans (2010)

WARNING: RELEASE THE SPOILERS!

Has there been a more truncated heroic cycle than “Clash of the Titans”? Our hero is a baby cast adrift, then he’s a son gazing at the horizon, then he’s an adult orphan bent on revenge, and with a mission, which takes one, two, three, four steps, after which he kills the big monster and banishes the big villain (for the sequel), and kisses the girl, and ... and that’s it. We ... are ...outta here.

This is the way we do things now. Our need to get on with the story reveals our contempt for the story. Maybe because we already know the story. “Tell us that one again, Daddy.” We’re adults now but we act like kids.

The story being told here is one of my least favorite for being so ubiquitous in the 21st century: the One; the Chosen One. It plays on our id, our early years, when the world revolved around us, when we were all chosen ones. When everything had a reason.

The story being told here is one of my least favorite for being so ubiquitous in the 21st century: the One; the Chosen One. It plays on our id, our early years, when the world revolved around us, when we were all chosen ones. When everything had a reason.

“You were saved for a reason,” Spyros (Pete Postlethwaite), Perseus’ foster father, tells a newly adult Perseus (Sam Worthington), as Perseus stands on the prow of the boat gazing longingly at the horizon. “And someday that reason will take you far from here.”

I’m so tired of this conceit. Should we turn it around? Hey, Fatso. There’s a reason you’re in this theater stuffing your face with an extra large tub of popcorn with extra butter and watching this crap. And someday that reason ...

Stop making no sense

In “Clash of the Titans,” which contains no Titans, the Gods create man but can’t live without man’s worship. That makes no sense. A group of humans from Argos, intent on worshipping King and Queen, tear down a statue of Zeus (Liam Neeson), invoking the wrath of Hades (Ralph Fiennes), who secretly despises Zeus. That makes no sense. After attacking the upstart Argosians, he kills, as a freebie, two innocent bystanders, Spyros and Marmara (Elizabeth McGovern), which makes no sense, but it enrages their son, a young Perseus, giving him his raison d’etre, revenge upon Hades, which he’ll forget in the second movie.

Despite this display of God power, the Argosians are determined, more than ever, to not worship the Gods, which makes no sense, and Cassiopeia (“Rome”’s Polly Walker) brags about the beauty of her daughter, Andromeda (Alexa Davalos), bringing down an even greater wrath. Hades shows up again, turns Cassiopeia to dust, disperses the Argosian soldiers, and promises to “release the Kraken,” a horrific monster, if Andromeda is not sacrificed for her mother’s effrontery. But Hades finds he can’t kill Perseus and immediately knows why: Perseus is a demi-god, the son of Zeus. He’s special.

Of course Andromeda’s father doesn’t want to sacrifice his daughter, so he sends his men, led by the stalwart Draco (Mads Mikkelsen), away from Argos, on a mission to kill the Kraken. This, too, makes no sense, since the Kraken is going to show up in a few days anyway. Why send your best men away from the city? Why not wait him out?

Right. Because “waiting him out” isn’t a story.

Zeus, half-son revealed, now has mixed feelings about the whole thing. He wants the Argosians punished, sure, but he doesn’t want to kill his half-son to do so. So he sends him a winged horse named Pegasus and an enchanted sword to protect him. But Perseus’ hatred for his absentee father is apparently greater than his hatred for the killer of his foster parents, and, initially, he refuses both gifts. He thinks he can get by without them. He’s an idiot without a personality. He’s an idiot only idiots can like.

Love? Fear? Release the Kraken!

Around this time we learn that Zeus lives off the love of man while Hades lives off their fear. So shouldn’t Hades be more powerful than Zeus? Isn’t fear more prevalent in us than love? At the least it’s worth a debate, a mention, a passing line or two. Here. Let’s trade two giant scorpions for 30 seconds of debate.

Nope. On we trudge, stupidly, to get the head of Medusa with which to beat the Kraken. Battles are engaged, soldiers fall, until we’re left with just the main dudes, the ones who have names. But all of them, even Draco, buy it in the underworld. Only Perseus, looked over by a kind of angel, Io (Gemma Artetron), who’s kind of hot, triumphs.

Nope. On we trudge, stupidly, to get the head of Medusa with which to beat the Kraken. Battles are engaged, soldiers fall, until we’re left with just the main dudes, the ones who have names. But all of them, even Draco, buy it in the underworld. Only Perseus, looked over by a kind of angel, Io (Gemma Artetron), who’s kind of hot, triumphs.

Of course, back in Argos, the people, led by a religious nut (Luke Treadway), are rightly worried about Zeus, Hades and the coming Kraken, so they grab Andromeda and tie her up on the cliffs above the sea, as an offering, and because it’s sexy. But at the last minute Perseus appears on Pegasus and yadda yadda. Hades appears and yadda yadda. Then Perseus and Andromeda kiss and ... Wait. He winds up with Io, not Andromeda. That makes no sense. Isn’t she a guardian angel? It’s like dating the tooth fairy.

So most everything that happens in “Clash of the Titans” is expected. The only unexpected moments are the nonsensical ones.

“The oldest stories ever told,” Io tells us in the beginning, “are written in the stars.”

Or in Hollywood.

Monday November 07, 2011

Movie Review: Haevnen/In a Better World (2010)

Waarning: Spřilers

Susanne Bier’s “In a Better World,” the English-language title for the Danish film “Haevnen,” which won the Oscar for best foreign language film at the 2010 Academy Awards, attempts to give a more adult answer to the dilemma Hollywood has spent 100 years exploiting: What do ordinary, law-abiding citizens do when confronted with bullies and psychopaths? How does a man face brutality without becoming brutal himself?

These films are now called vigilante films, since, in them, ordinary citizens go beyond the law to set things right (see everything from “Death Wish” to “Harry Brown”), but they were once simply called westerns. The hero that emerged, often John Wayne, didn’t have to worry about going beyond the law because there was barely a law. He also shot second. (He was eminently fair.) There was also no blood, no rape, no none of that. Hays Code.

In “Haevnen,” Elias (Markus Rygaard), buck-toothed and braces-wearing, is the picked-upon kid at his local school, whose hallways are ruled by Sofus (Simon Maagaard Holm) and his crew of toadies. They block entranceways, demand obeisance, and hurt and humiliate those they don’t like. Elias, sweet-natured, is a favorite target.

In “Haevnen,” Elias (Markus Rygaard), buck-toothed and braces-wearing, is the picked-upon kid at his local school, whose hallways are ruled by Sofus (Simon Maagaard Holm) and his crew of toadies. They block entranceways, demand obeisance, and hurt and humiliate those they don’t like. Elias, sweet-natured, is a favorite target.

Then Christian (William Jřhnk Nielsen), Danish, but recent of London where his mother died of cancer, arrives on the scene. He’s no bigger than Elias, and both are smaller than Sofus, but he moves through life with an intense glare. The first day he scopes out the scene like a little Clint Eastwood, stands up to Sofus (for which he gets a soccer ball in the nose), and the next day, when Sofus follows Elias into the boys’ room to further pick on him, Christian follows and attacks Sofus with a bike pump and a knife, leaving him bloody and moaning on the floor. It’s like John Foster Dulles’ 1950s foreign policy of massive retaliation except in a Danish middle school.

School officials, absent or impotent for the reign of Sofus’ terror, now, of course, get involved. The knife is particularly troublesome—it’s apparently the Danish equivalent of bringing a gun to school—and parents are called and admonished; but both boys stand firm, the knife is never found, and Sofus’ reign ends. Half an hour into the film.

That itself is intriguing. In the typical vigilante film, you get your moment of revenge in the third act, not the first, and it pretty much ends the movie. Now we’re left wondering what’s going to happen next. (At the same time, it doesn’t mean we didn’t thrill to the beating of Sofus, the little shit, any less than we thrill to the revenge perpetrated against any number of cinematic bullies. First or third act, the desire for justice of a violent nature is still there.)

I suppose that’s the question of “Haevnen”: Can we have a justice that’s not violent? That’s within the law? That’s adult?

Anton (Mikael Persbrandt), the father of Elias, attempts to find out. Well, he doesn’t attempt to find out. It’s less proactive than that. He just finds out. Kind of.

Anton spends half his time as a doctor-without-borders in sub-Saharan Africa, treating the sick and the injured. The latter group, increasingly, is filled with pregnant women whose stomachs have been slit open. Why? Who could do such a thing? Turns out, the local chieftain, Big Man (Odiege Matthew), who bets compatriots on the gender of the unborn babies of passing pregnant women. Cutting them open is a way to settle the bet.

It’s in Denmark, though, that Anton finds his bully. One day, chaperoning his two boys and Christian near the docks, Morten (Toke Lars Bjarke), Elias’ younger brother, pulls away and gets into a fight with another boy over a swing. When Anton tries to break it up, the father of the second boy shows up, belligerently objects to Anton touching his son, and slaps Anton in the face several times. It’s a shocking moment—for both us and the kids. It’s also shocking for Anton, who keeps his cool but cools off his injured cheek (and injured spirit?) with a swim in the family lake at dusk.

In a better world, Anton would forget about the incident. Unfortunately, now his son thinks him a coward. So after the boys have tracked the bully, Lars (Kim Bodnia), to his workplace, Anton shows up, with boys in tow, and confronts him. Except Lars feels no shame, just maliciousness, and again slaps Anton repeatedly. It’s an interesting scene. Anton is confrontational but peaceful, and shows no fear, and questions every move Lars makes. Afterwards, outside, he claims that Lars showed himself to be a big jerk not worth anyone’s time or attention. He says Lars lost. But Christian annunciates our thoughts: “I don’t think he thinks he lost.”

This sets up the second half of the movie: Anton, in Africa, dealing with an injured Big Man, and Elias and Christian, in Denmark, scheming against Lars. In his grandfather’s garage, Christian finds old fireworks and uses their gunpowder to create a bomb with which to blow up Lars’ car.

In the end, retribution against Lars is premeditated and comes with complications (Elias is caught in the blast), while retribution against Big Man is impulsive and ... without complications? Anton treats Big Man for an infected leg for several days, but when Big Man makes a joke about a girl who dies on Anton’s operating table, Anton loses it and shoves him and his entourage—two unarmed men—into the courtyard. The two men flee, while Big Man is left helpless on the ground. The citizens gradually close in on him and tear him apart.

If there are complications for Anton’s actions, they are internal, within Anton, never external. At no point, for example, do any of Big Man’s men take revenge. Because they wanted Big Man gone, too? Who knows? It’s all left hanging. Does Anton feel less culpable about Big Man’s death because it wasn’t by his own hands? Does he feel disappointed in the citizens who tear him apart? Does he revel in the revenge, as most of us, from the safety of our theater seats, do?

Every answer “Haevnen” offers is dissatisfying. Most, one imagines, are purposefully so, but the movie is dissatisfying in other, seemingly unintentional ways. How, for example, does Christian become a 10-year-old Clint Eastwood in the first place? Solely through the death of his mother? He apparently learns his lesson—or a lesson—about his violent ways by almost causing the death of Elias. But how long does the lesson hold? And does Anton feel any culpability here? If he’d simply stood up to Lars, or called the cops on him, the boys wouldn’t have felt the need to take action themselves. What’s the better world of the title: one in which Anton stands up to Lars or one in which Lars doesn’t exist?

The cinematography is gorgeous and the acting excellent—particularly William Jřhnk Nielsen’s astonishing turn as Christian, for which he was nominated best actor at the Danish Academy Awards. But “Haevnen” still feels weak for a best foreign language film winner. We watch for two hours and no insight, great or small, comes.

Monday March 28, 2011

Movie Review: Morning Glory (2010)

WARNING: THERE ARE NO SPOILERS IN A MOVIE THIS OBVIOUS

In “Morning Glory,” an enthusiastic, workaholic TV producer, Becky Fuller (Rachel McAdams), lands a gig with a floundering national morning news show, “Daybreak,” and does whatever she can to turn the show into a success.

Also in “Morning Glory,” an enthusiastic, workaholic actress, Rachel McAdams, lands the lead in a floundering star vehicle, “Morning Glory,” and does whatever she can to turn the movie into a success.

Becky succeeds. The way she succeeds is part of why Rachel fails.

Unlikeable but right

Unlikeable but right

As the movie begins, Becky is the producer of “Good Morning, New Jersey,” which has just been bought by a conglomerate, and in the reshuffling everyone expects her to get promoted. Subordinates wear T-shirts reading, “Way to go, Becky!” and Becky wears a T-shirt into her boss’s office reading, “Yes, I accept!” Instead of getting booted up, of course, she gets booted out. Cue box of personal items and crying subordinates, still wearing their “Way to go, Becky!” T-shirts, in the parking lot.

That’s not a bad scene, actually. They telegraph it, but something about those T-shirts in the parking lot forgives the telegraphing.

No, the first real red flag of the movie is subsequent to that, when Becky’s mother (Patti D’Arbanville, “Lady D’Arbanville” Cat Stevens fans) has a heart-to-heart with her. She tells her it’s time to give up on her dreams. She tells her those dreams used to be cute but now they’re just ... embarrassing. She tells her to stop now, please, before her life becomes tragic.

Really, Mom? Your daughter just got fired through no fault of her own? From a job she was obviously good at? And this is your advice? It’s not like she’s 28 and wants to be a ballerina. She just wants to be a producer. She wants to work in TV. Maybe if you’d given a speech about how it’s 2010, and TV is dying, and you need to look to the future and try something Twitterish or YouTubeish, we would’ve half-bought it. Maybe if you’d owned up to how volatile the world seems, and how no job, no profession, no career seems safe in these shifting times, you would’ve connected Becky and her problems to us and ours, in a way that felt meaningful, and we would’ve cared more about the movie. Instead ...

Of course this speech was designed (by screenwriter Aline Brosh McKenna, director Roger Michell) to make Becky more sympathetic. It provides a kind of false tension in the first 10 minutes. She needs to show her mother! And quickly! Which she does. She lands a plum (or plummish) gig as producer of the IBS network’s fourth-place morning show: “Daybreak.”

When she arrives, the doorknobs don’t work, the staff is lethargic, the cohost, Paul McVee (Ty Burrell) is a sex pervert. So she energizes the staff by firing the co-host. But her boss, Jerry Barnes (Jeff Goldblum—always welcome to see), rather than applaud the move, tells her she has no budget for a new cohost. So she has to pick someone already contracted to, but not really working for, the IBS family.

Ah, but there is someone in this category. A legend, actually: Mike Pomeroy (Harrison Ford, all wrong for the role), a Mike Wallaceish, crotchety, old-school TV newsman, and, according to hunky fellow IBSer, Adam Bennett (Patrick Wilson), “the third worst person in the world.” Through a kind quirky persistence, she lands both the hunky Bennettt (in bed) and the crotchety Pomeroy (in the co-host chair). But while the former is accommodating and tight-abbed in the Hollywood manner, the latter fights and grumbles all the way.

He’s full of himself. He has ego battles with co-host Colleen Peck (Diane Keaton) over who gets to sign off the show—not a bad bit, actually—even though he doesn’t care a wit for the show. He insists on announcing only depressing news, or “news.” He thinks shows like “Daybreak” are contributing to the decline and fall of western civilization.

Problem? He’s right but unlikeable. He’s so serious he makes the real Mike Wallace seem like Richard Simmons in comparison. He’s so gruff he even has a growly voice, which doesn’t work for TV news at all. Listen to Wallace, Safer, Koppel. Their faces may be craggy but their voices are smooth. Harrison Ford? He’s virtually expectorating every word he says. He's Demi Moore with bronchitis.

Likeable but wrong

Bigger problem? Becky, our heroine, is likeable but wrong. We want her to win, but to win, to get the ratings up so the show isn’t canceled, she has to make her show sillier. She does this with enthusiasm. She puts the weatherman on a roller coaster. She makes him skydive. His horrified reaction makes everyone laugh and he becomes “a YouTube sensation.” Now Colleen wants in on the action. She bakes this, she dances with that, has animals on her show. Animals! And funny things happen with them! Oops, here comes a sku-u-unk...

But by aiming low, by making the fluffy show fluffier, the ratings go up, they get new doorknobs, and Becky is called into the offices of the “Today” show to become their producer. Will she abandon what she’s created, and her team of misfits, to take her dream job? Of course she won’t. This is a movie, not life. So Mike Pomeroy, realizing he’s about to lose the producer who saved the show he never wanted to be on in the first place, makes an impromptu frittata on camera, to show that he’s loosened up; and Becky, about to take the job in the “Today” show offices, sees him do this—because NBC apparently displays all their rivals’ TV shows in their corporate offices—excuses herself, and runs across town to get back to him in time. In time for what? For the frittata? The tension is past. Her choice is made. That was the tension. No, she runs for pretend tension: so she can be in the wings and smile at Mike Pomeroy as he signs off.

Lord.

You know what might’ve been a cool movie? “An award-winning TV journalist, Mike Pomeroy (Donald Sutherland), is forced to take a job on a morning news program, where his standards keep getting lowered until his overly enthusiastic producer, Becky (Rachel McAdams), asks for one final humiliation.” Think of it as “Morning Glory” mixed with “Blue Angel.”

Or this? “A likeable, quirky TV producer, Becky (Rachel McAdams), continually lowers the standards of her morning news show to get the ratings up, but it doesn’t work and the show is canceled.”

I know. Neither would ever get made. But in a way the latter one did. “Morning Glory,” a movie that continually lowered its standards to give movie audiences what they wanted, wasn’t what people wanted. It opened last November and sank without a trace.

Sunday March 06, 2011

Movie Review: “Secret Origin: The Story of DC Comics” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS OF STEEL

It’s immediately suspect, isn’t it? “Secret Origin: The Story of DC Comics,” produced by DC Entertainment. Most corporations can’t police themselves let alone document themselves. Gonna suck. Gonna sweep shit under the rug.

And it does. We get Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster creating Superman in 1938, and, according to Bob Kane, earning $800 a week a year later, but not being shunted aside in the 1940s by DC, then forgotten, then scraping out an existence while their creation soars to new heights, until, in the 1970s, to prevent bad publicity  prior to “Superman: The Movie,” Warner Bros. finally, meagerly compensates the two for changing the world. We get Captain Marvel outselling even Superman in 1940, but not the eight-year-long lawsuit by DC that kills that creation as well as Fawcett Publications. We get editor Julius Schwartz and Mort Weisinger rescuing Superman in the late ‘50s by inventing Supergirl and Superdog and Supercat and Superhorse and Supermonkey, but no word on how all of this super crap essentially buried the Man of Steel under layers of irrelevance just as Marvel Comics was about to make comic books relevant again.

prior to “Superman: The Movie,” Warner Bros. finally, meagerly compensates the two for changing the world. We get Captain Marvel outselling even Superman in 1940, but not the eight-year-long lawsuit by DC that kills that creation as well as Fawcett Publications. We get editor Julius Schwartz and Mort Weisinger rescuing Superman in the late ‘50s by inventing Supergirl and Superdog and Supercat and Superhorse and Supermonkey, but no word on how all of this super crap essentially buried the Man of Steel under layers of irrelevance just as Marvel Comics was about to make comic books relevant again.

The first words in the doc don’t help. A dude who turns out to be Neil Adams defends comics through hyperbole. “There is no better medium than comic books,” he says. “It’s the medium.” A second later he defends comics through a kind of quotidian consumerism. “You may not like comic books, you may not respect comic books, but they’re something that people buy for themselves that they want to read.”

Really? That’s your open?

Yet “Secret Origins” isn’t bad. Some shit even stays on top of the rug. Gerard Jones, author of “Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book” (a must-read), talks up the gangster contacts of Harry Donenfeld, along with the near-pornography status of his early pulps, before he and accountant Jack S. Liebowitz partnered with Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson of National Allied Publications and created “Detective Comics #1.” Both Jones and comic book writer Mark Waid, all half-smiles and shrugs, talk up the bondage fixation of Wonder Woman’s creator, William Marston, which was translated to the comics page with breathtaking regularity. Stan Lee and Marvel Comics get their 30 seconds, too, which is 30 seconds more than I thought they’d get, while Denny O’Neil offers a charming, heartfelt mea culpa for taking away Wonder Woman’s powers in the early 1970s: “What I did, in effect, was take the feminist icon and depower her, dial her way down, and then to compound the sin give her a mentor [I-Ching] who is a male, and then, to compound that sin, named that male after one of the classics of Chinese literature.” A grimace and an eye-roll. “Hoo!”

The doc, to its credit, doesn't ignore the bondage fixation of William Marston, Wonder Woman's creator.

Talking heads often make the doc and “Secret Origins” is as packed as the Justice League in this regard: Not just Jones and Waid and O’Neil but Chip Kidd, Neil Gaiman, and Len Wein. We get archival footage of Bob Kane behind the wheel of the 1960s Batmobile (the coolest car ever) and Alan Moore recounting that first phone call from Len Wein offering him “Swamp Thing.” The doc takes us from the mid-1930s and “Fun” comics to the constant reboots of today.

Some of the footage is truly archival. Here’s a kid caught up in early Supermania:

Here’s “Superman Day” at the World’s Fair in 1940:

Chip Kidd, unlike Adams, is charming in his hyperbole:

I think the Fleischer Superman cartoons are a pinnacle of cinematic achievement in the 20th century. I’m sure people will laugh at me for saying that. But they’re like beautiful little poems that I never get tired of viewing.

How good are these cartoons? Near the end of the doc, there’s a nice juxtaposition of Max Fleischer’s cartoon Superman stopping a plane from crashing (in 1941) with Bryan Singer’s live-action Superman stopping a plane from crashing (in 2006), and they’re so similar one wonders if the former didn’t inspire the latter.

The mighty Superman, in 1941 (top) and in 2006.

Unfortunately, Singer isn’t a talking head here. His Superman is being rebooted by Zack Snyder so he’s literally out of the picture.

DC frames their story—correctly I believe—as one of invention followed by stagnation, followed by the next generation’s invention. Thus the company went from messy, creative, 1940s sweatshop to surviving by tiptoeing through the reactionary 1950s to a burst of Julius Schwartz-directed activity just before 1960 (the origin of the modern Flash is particularly interesting), which led indirectly to the resurgence of Marvel, which led DC to attempt, breathlessly, to catch up with stories of poverty and drug abuse from the younger generation (Adams; O’Neil), and which ultimately led to the astonishing reboots and darker visions of Frank Miller and Alan Moore in the 1980s. But the 1990s saw excessive darkness and vigilantism from Miller/Moore acolytes, so Alex Ross and Mark Waid created the “Kingdom Come” series, in which Superman, etc., returned to battle the new amoral superheroes. Post 9/11, apparently, we got a return to the superhero as wish-fulfillment. At least that’s what’s implied here but the modern era is out of my purview. (To me it feels like it’s all one-shots and reboots.)

So much is missing. We get tears, literal tears, on the overhyped “Death of Superman” in 1994 but nothing on John Byrne’s “Man of Steel” reboot or Marv Wolfman’s “Crisis on Infinite Earths” maxi-series. We get the 1950s “Adventures of Superman,” the 1960s Adam West “Batman” and the 1970s “Superfriends”; but no mention of the 1940s Superman/Batman serials (two each), the 1960s Broadway musical, “It’s a Bird, It’s a Plane, It’s Superman!,” nor the 1960s “Superman/Aquaman Hour."

So many issues (no pun intended) are left untouched:

- What does it mean to kill off continuity with reboots and one-shots? Continuity leads to stagnation and the weight of history, but reboots lead to ... what? Frivolity? None of it matters because none of it is the story. It's all imaginary tales now.

- Does the increasing sophistication of comic books, and their marginalization into specialty stores, mean losing younger generations of fans?

- What are sales like these days? Are comic book characters thriving in other media (“Spider-Man,” “The Dark Knight”) even as comic books themselves struggle to survive anemic sales?

- The biggee: Why did superheroes emerge when they did? What were the nearest forerunners to superheroes in the 19th century? In the 14th? In 29 A.D.?

All of which means, I suppose, that the great documentary on Superman, or DC Comics, or the long history of comic books in general, still needs to be written.

Same Bat-time, kids.

Wednesday February 16, 2011

Movie Review: “The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest” (2010)

WARNING: SPÖILERS III

“The Girl Who Kicked the Hornet's Nest”? Really? How about “The Girl Who Lies in Bed While a Bunch of Old, Decrepit Hornets Buzz their Last Buzz”? If some trilogies follow the Hegelian pattern of thesis/antithesis/synthesis, the Millennium trilogy goes a slightly different route: thesis, thesis, anesthesia. I felt nothing but sleepy here.

The thesis of the series is in its Swedish title, “Män som hatar kvinnor”: “Men Who Hate Women.” So “Dragon Tattoo,” the first film, gives us not only Martin Vanger, a Swedish Nazi who has been torturing, raping and killing women for 40 years, but, for extra credit, Nils Bjurman, lawyer, guardian, and rapist of our fidgety, feral heroine, Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace). Both villains get theirs. The second film, “Played with Fire,” brings back Bjurman for a final bow before kicking him to the curb. There are also allusions to human trafficking, but these gets buried when it’s discovered the man running the sex trade, Alexander Zalachenko (Georgi Staykov), is Lisbeth’s father, whom fire played, while his blonde, brutish henchman, Ronald Niedermann (Micke Spreitz), is the half-brother she never knew she had. These guys hate, sure, but they overflow our thesis. They’re EOE. They hate everybody.

By the third film? We’re left with Dr. Peter Teleborian (Anders Ahlbom), the director of the institute where 12-year-old Lisbeth was incarcerated after she played with fire. Apparently he was in the second film, too, but I don’t remember him. Apparently he tied up Lisbeth for more than a year of her two-year-stay, and there are allusions he abused her, along with vague, grainy, flashback footage. But he’s a toothless beast now, more pathetic than horrifying. When not the main government witness in a trial to incarcerate Lisbeth again, he jerks off to child porno.

“Hornet's Nest” is less revelation (for us) than attempted cover-up (by the powers-that-be). Because Lisbeth survives that bullet to the brain from the second movie, and her father, Zalachenko, survives that axe to the head from the second movie, the authorities are intent on charging her with attempted murder (of him), and him with ... isn’t it also attempted murder? Of her? So shouldn’t these two charges off-set each other somewhat? Someone, anyway, has a good self-defense argument.

“Hornet's Nest” is less revelation (for us) than attempted cover-up (by the powers-that-be). Because Lisbeth survives that bullet to the brain from the second movie, and her father, Zalachenko, survives that axe to the head from the second movie, the authorities are intent on charging her with attempted murder (of him), and him with ... isn’t it also attempted murder? Of her? So shouldn’t these two charges off-set each other somewhat? Someone, anyway, has a good self-defense argument.

Old, powerful men keep gathering. They talk in hushed tones. They need things hush-hush for the remainder of their sad lives and will do anything to make it so. Example: Zalachenko, from this hospital bed, demands protection from the powers-that-be or he’ll implicate them. He’ll spill the beans. He says to Evert Gullberg (Hans Alfredson), “You have no choice.” To which Gullberg, who reminds me of former baseball manager Bill Rigney, sagely replies, “Life has taught me there’s always a choice” and promptly shoots Zalachenko in the head. Then he goes after Lisbeth. But the door to her hospital room is barricaded, and after one or two feeble attempts, oof, he sits down, an old man on a waiting room bench, to catch his breath. Then he puts the gun to his cheek and pulls the trigger.

“What are these guys trying to cover up again?” I asked Patricia halfway through the film.

“That stuff about Zalachenko,” she replied. “How he worked for them. How they protected him.”

“That’s it?”

There really is nothing new here. We already know what the truth is. So do the main characters. We’re just waiting to see if the rest of Sweden will catch up. Shocking revelations are made in Millennium magazine: the stuff from the first two movies. Shocking revelations are made in court: the stuff from the first two movies. Basically we get to watch while lawyers and judges watch plot points from the first two movies and agree how horrific it all was.

It’s an odd trilogy, isn’t it? Men who hate women, sure, but also men who nurture women. Or a woman. How many good men does Lisbeth have on her side to offset the bastards? Count ’em off:

- Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist), our journalist hero.

- Dragan Armanskij (Michalis Koutsogiannakis), her employer from the first film, who does some investigative work for Blomkvist in this one.

- Holger Palmgren (Per Oscarsson), her first guardian.

- That boxer from the second movie, Paolo Roberto, who kicks ass.

- Plague (Tomas Köhler), the computer hacker, always there to act as a modern deus ex machina, extracting information, as it became necessary, from other people’s computers. This is never more true than at the end of “Hornet's,” when he saves the day and is then forgotten. All credit goes to Blomkvist.

- Finally, “Hornet's” gives us Dr. Anders Jonasson (Aksel Morisse), the surgeon who extracts the bullet from Lisbeth’s brain. She barely says anything to him but he’s quickly smitten. He keeps the police at bay for her. He buys her pizza when she wants it. He gives her gifts: a book on DNA. She nods her thanks.

As for the women? For a trilogy that feels feminist, the women, with the exception of Lisbeth, are kind of lame.

In the first movie there’s Harriet Vanger, who would rather let her brother rape and kill for 40 years than confront him or even warn the authorities about him.

Erika Berger (Lena Endre), the publisher of Millennium, is a wishy-washy mess. In “Hornet's” she gets a few threatening emails warning her not to print the magazine with Lisbeth’s story in it. Then a rock is thrown through her window. What does she do? She decides not to print the magazine with Lisbeth’s story in it. Hardly Katie Graham.

One has higher hopes for Annika Giannini (Annika Hallin), Blomkvist’s sister, pregnant, and a no-nonsense lawyer, but she disappoints, too. She takes Lisbeth’s case reluctantly, grumbling all the while, as a favor to her brother, even though it’s probably the biggest case in the country. Does she do investigative work? Who knows? Everything seems handed to her. Blomkvist gives her Lisbeth’s story, along with documentary evidence of some of the authority abuse she suffered (a DVD of the Bjurman rape), but she doesn’t seem to know what to do with it. When the main government witness, Teleborian, claims the Bjurman rape is part of Lisbeth’s paranoid schizophrenia, Annika doesn’t introduce the DVD into evidence to discredit him. Not immediately. We still have half an hour of film to watch. So she wrings her hands, and whines, until Plague, hacking Teleborian’s computer, delivers the coup de grace: evidence that Teleborian created his diagnosis of Lisbeth before even seeing Lisbeth. Plus there’s all that kiddie porn. Plague hands off to Blomkvist who hands off to Annika, who finally makes her case. Hardly Maureen Mahoney.

Even Lisbeth seems to regress in the third film. Remember the first film? She was almost too interesting there: tough, feral, a computer hacker with a photographic mind who saves the day and vanishes like the Lone Ranger, leaving Blomkvist and us to wonder: “Who was that stoic girl?”

In the second film she begins to let people in—Blomkvist literally—but by the third film, with her hacking skills and photographic mind a thing of the past, she has trouble just saying tack. The “Godfather” trilogy suffered from its Arte Johnson-like ending (an ancient Michael Corleone falling off a park bench and dying), and the Millennium trilogy, which ain’t nearly in the same category, suffers from its almost shrug of an ending. Lisbeth, sure, takes care of Niedermann, who shows up like a Bond villain in the denouement; then she takes a bath. Blomkvist comes by. They exchange awkward greetings. She finally says what she hasn’t been able to say, tack för allt, thank you for everything. Should the movie have ended there? With a close-up of her face? Or his? Instead we get more awkwardness, then a flat, distant shot of Stockholm from the water; then the credits start rolling. Hej dĺ.

For all my problems with the series, the girl with the dragon tattoo, who played with fire, who kicked the hornet's nest, deserved a better ending than this.

Saturday February 12, 2011

Movie Review: “Biutiful” (2010)

WARNING: THE ROAD TO HELL IS PAVED WITH GOOD SPOILERS

The world of Alejandro González Ińárritu (“21 Grams,” “Babel”) tends to be a polyglot of crowded, marginal characters. It’s a world where everyone ekes a living off of each other, and what light there is is fluorescent. Halfway through his latest, “Biutiful,” the sun shines on a family eating breakfast together. “Ah, the sun,” I thought. Then it goes away. The sun is for other people’s movies.

Ińárritu is all about border crossings. At the start of “Biutiful,” Uxbal (Javier Bardem) is facilitating between two immigrant groups, the illegal Chinese and the legal African, in Barcelona. The former make bootleg products in basement factories, which the latter then sell along Las Ramblas or in the Plaza Cataluńa. Uxbal bribes la policia to look the other way.

He’s also clairvoyant. Did I mention that? He can communicate with the recently dead and help them cross that final border to the undiscovered country from which no traveler returns. I should add that never has such a gift been presented in such by-the-way fashion in a movie. Uxbal has an answer to the most profound question in human history—does the individual consciousness survive death?—and he views it like it’s pro bono work, like it’s a hobby. He does it on the side when he has the time.

He’s also clairvoyant. Did I mention that? He can communicate with the recently dead and help them cross that final border to the undiscovered country from which no traveler returns. I should add that never has such a gift been presented in such by-the-way fashion in a movie. Uxbal has an answer to the most profound question in human history—does the individual consciousness survive death?—and he views it like it’s pro bono work, like it’s a hobby. He does it on the side when he has the time.

Despite this gift, Uxbal’s life is no great shakes. He lives in a cramped, basement apartment with his two kids. His ex-wife, Marambra (Maricel Alvarez), is bipolar, an addict, and sleeping with his brother. He’s really only a step or two up from the immigrants he’s helping or exploiting. Then he’s diagnosed with cancer and given months to live.

So is this going to be that kind of story? The inconsequential man, forced, by the proximity and sudden inevitability of death, to see the beauty of life? Yes, there’s some of that. Uxbal is a hulking figure for much of the first third of the film. (You realize what a powerful back, and what a huge head, Bardem has.) After his diagnosis, he softens a bit. He visits his clairvoyant mentor, who tells him, “Put your affairs in order.” Both she and he know that the biggest problem for the recently dead is worry over unresolved matters, which get them to linger, to remain where they shouldn’t, and neither wants that for Uxbal.

So Uxbal begins to put his affairs in order. He tries to help the Africans, who are being deported for selling drugs. He tries to help the illegal Chinese immigrants, who live in horrible conditions, by buying them space heaters. He reconnects with Marambra, who still loves him, and he and the kids move into her apartment. They have breakfast together. The sun shines through the window. Life is good.

But life, as short as it is, lasts longer than “good.” The Africans are deported despite Uxbal’s efforts. Marambra goes back to partying, and doing drugs, and she beats the youngest, Mateo (Guillermo Estrella), forcing Uxbal to move everyone back into his basement apartment, which he’s already given to Ige (Diaryatou Daff), the wife of one of his deported Africans.

Most horrific: the heaters Uxbal buys for the Chinese immigrants—made, no doubt, by people under conditions similar to theirs—don’t work properly. Ińárritu telegraphs the moment. Twice in the movie we see the Chinese foreman unlock the doors to wake the workers at 6:30 a.m., but both times we’re inside the room. The third time Ińárritu places the camera outside the room, over the foreman’s shoulder. The door opens and, lo and behold, dozens of dead bodies lying on the floor. Patricia, watching next to me, gasped in horror, but I was only surprised that it was an apparent gas leak. I was expecting charred bodies burnt to a crisp.

So now Uxbal has dozens of deaths on his conscience just as he’s dying himself. How does he deal with the weight of all this? Poorly or not at all. He makes a few motions, feints in several directions, but he’s really too busy dying to do anything proper. He withers, wears diapers, is confined to bed. Ige begins to watch his kids, to feed them. Will she be his savoir? On his deathbed, Uxbal gives her money to pay a year’s rent, so at least his kids will have a place to live for a year, but she uses the money to travel back to Africa and her husband. She abandons his for hers.

Every attempt to put his affairs in order, in other words, leads to chaos and heartbreak. It’s as if a sick God is foiling his every move. One is.

What is it about Ińárritu? He deals with themes I care about but his execution always bores me. His scenes are gritty but peculiarly weightless and airless. He shoves too many characters on the screen, shrinking them to make them all fit. He pisses me off.

I did like two scenes, however, shown both the beginning and end of the movie.

In the first scene, the camera focuses on two pairs of hands, male and female, and we hear voices, male and female, talking about a diamond ring. “Is it real?” she asks. Yes, he answers. She wants to wear it. He lets her. It could be a young couple, postcoital, at the beginning of their journey, but by the end of the movie we know it’s Uxbal and his daughter, Ana (Hanaa Bouchaib), and the conversation is the last he will have in this world.

In the second scene, Uxbal is in the woods eyeing a handsome young man. They smoke cigarettes and have an odd conversation about owls. The man, younger than Uxbal, shorter than Uxbal, seems the dominant one, while Uxbal has a kind of shy, flirtatious love shining in his eyes. Initially confusing, by the end of the movie we know the man is Uxbal’s father, who died when Uxbal was young, which means Uxbal is now dead. This is the afterlife. But it’s almost like a dream, isn’t it, pieced together from life in the way of dreams. Freud once observed that anything we hear in a dream we first hear in life, and so it is with the conversation about the owls. Initially it was Mateo’s conversation to Uxbal. The woods themselves seem culled from a refrigerator drawing of Mateo’s: childish woods beneath the word “biutiful.”

But this is only the beginning of death. In the woods, Uxbal’s father moves away, and Uxbal says “What’s over there?” He follows him. The camera stays behind. And that’s where the movie ends.

Patricia loved it. When the lights came up I looked over and her cheeks were soaked with tears. For a moment it made me question my own nonplussed reaction. But only for a moment.

Ińárritu is all about border crossings but his movies don’t inspire any border crossings in me. They don’t take me any place I haven’t been or want to go. I remain (stubbornly? frustratedly?) on this side, in the place I started.

Monday February 07, 2011

The Tardiest and Positively Last List of TOP 10 MOVIES OF 2010

The movie year increasingly reminds me of the old video game “Space Invaders.” In the beginning, the invaders drop down intermittently and at a snail's pace—easy pickings—but as the game progresses they come fast and furious until you can't keep up, and then ... Blam! Game over.

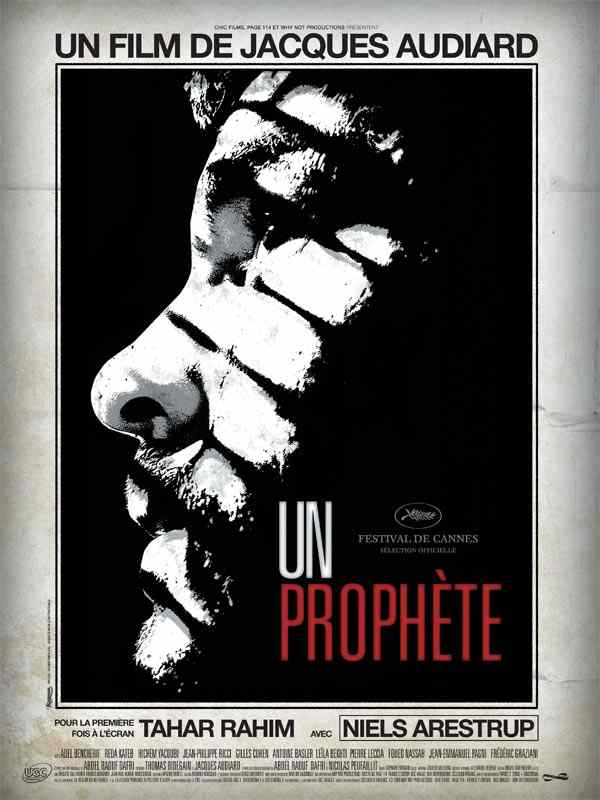

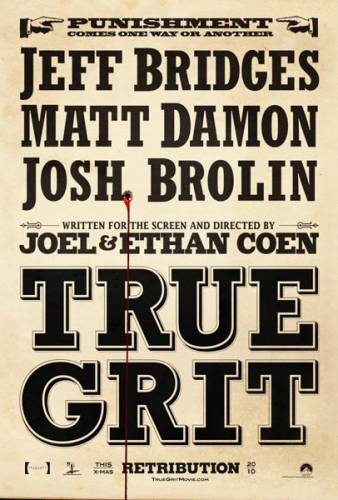

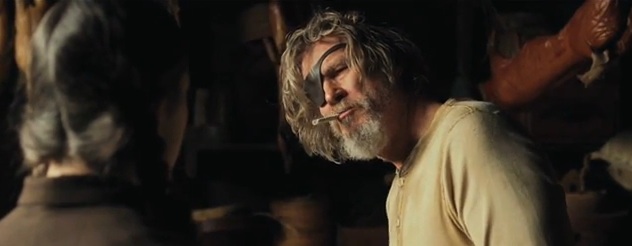

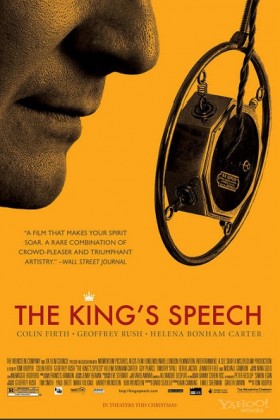

That's my movie year. It starts out slowly, luxuriously, with huge gaps between one good film (“The Ghost Writer”) and another (“Un Prophete”). The dashed hopes of spring (“Kick Ass”) eventually give way to the heat of summer blockbusters (“Toy Story 3”; “Inception”). In fall, there's September pretenders (“The American”), October surprises (“The Social Network”), but before you know it you‘re inundated (“Black Fair Rabbit Fighter Job Speech Grit”) until ... Blam! Game over.

Long way of sayng I should’ve posted this sooner but kept trying to pick up all those I missed. Then I looked around and it was February and I knew I had to go with what I‘ve got.

This is what I’ve got.

10. “Inside Job” is the first of three documentaries in my Top 10. It's the least powerful but probably the most necessary since it goes into the whys and hows of the global financial meltdown, which most of us, including especially me, don't quite understand yet. The talking heads we want  (Henry Paulson; Larry Summers) aren't talking, of course, but enough middle-management types, flattered to be asked, are. My favorite? Little Freddy Mishkin, tanned and suited up, who hems and haws through a series of questions, including one on a 2006 independent study he co-authored, for $125,000, for the Icelandic Chamber of Commerce. He called it “Financial Stability in Iceland.” This was just before the Icelandic economy collapsed disastrously. So now in his CV it's called “Financial Instability in Iceland.” When questioned on the switch, he responds with his usual grace: “Well, I don't know, if, whatever it is, is, the, uh, the thing—if it's a typo, there's a typo.” Review excerpt:

(Henry Paulson; Larry Summers) aren't talking, of course, but enough middle-management types, flattered to be asked, are. My favorite? Little Freddy Mishkin, tanned and suited up, who hems and haws through a series of questions, including one on a 2006 independent study he co-authored, for $125,000, for the Icelandic Chamber of Commerce. He called it “Financial Stability in Iceland.” This was just before the Icelandic economy collapsed disastrously. So now in his CV it's called “Financial Instability in Iceland.” When questioned on the switch, he responds with his usual grace: “Well, I don't know, if, whatever it is, is, the, uh, the thing—if it's a typo, there's a typo.” Review excerpt:

Most of us struggle to find something we’re good at, and for which we can get paid, and, if we’re lucky, we do this thing for 40 to 50 years until we can hopefully retire with a bit of comfort. And while we’re doing this thing, we’re putting our money, bit by bit, into a room, which is where other people, bit by bit, are putting their money, too. So there’s a huge pile of money in this room. Now there’s another group of people who are attracted to this room for the pile of money. They believe they can take that pile of money, our money, and turn it into a bigger pile of money, a lot of which will be their money. But while they’re doing this magic act, they don’t want anyone to watch. Because we can trust them. Because they are self-regulating. Because what could possibly go wrong?

9. I had problems with “The Ghostwriter,” particularly the ending, in which the Ghost (Ewan McGregor) figures it all out then gives it all up to his  enemies, the faux-Bush administration, and dies two seconds later. It's as if U.S. government agencies are quick, coordinated and supersmart rather than the slow, clumsy battleships we know them to be. So I never thought this movie would make my top 10. It's the weight of it that finally won me over. It's the images that stayed in my head: the lone SUV, alarm blaring, on the ferry; McGregor next to the full-paned window revealing the dunes outside—making it appear he's half in the room and half out; the unsexy sex scenes; the investigation through GPS; the cold and the gray and the paranoia of it all. For all the problems with story, the feel of it was created by a true artist. Review excerpt:

enemies, the faux-Bush administration, and dies two seconds later. It's as if U.S. government agencies are quick, coordinated and supersmart rather than the slow, clumsy battleships we know them to be. So I never thought this movie would make my top 10. It's the weight of it that finally won me over. It's the images that stayed in my head: the lone SUV, alarm blaring, on the ferry; McGregor next to the full-paned window revealing the dunes outside—making it appear he's half in the room and half out; the unsexy sex scenes; the investigation through GPS; the cold and the gray and the paranoia of it all. For all the problems with story, the feel of it was created by a true artist. Review excerpt: