Movie Reviews - 1930s posts

Wednesday October 19, 2022

Movie Review: Shadows Over Shanghai (1938)

WARNING: SPOILERS

So this is where Edward Woods wound up.

In case you don’t know his story: Woods lost the starring role in the 1931 gangster flick “The Public Enemy” when, a few weeks into production, the writers, the director and eventually the producer realized, “You know, this Cagney fellow has some verve and snap to him,” and switched their roles. The decision relegated Woods to second banana, which seemed to seal his fate. For the rest of the decade, he was mostly fourth-billed in increasingly cheaper productions, until this final straw, his last film role: sixth-billed in a shitty Poverty Row production and acting opposite a woman so wooden she could attract termites.

He plays Peter, the deliverer of the film’s maguffin. His sister Irene (Lynda Grey, the wooden one) works at the Woosung Refuge for War Orphans, and one day she and a gray-haired elder are talking paternalistically about their Chinese charges when a plane flies overhead. No, two planes. She assumes it’s Peter and a friend, but it’s not a friend. It’s the movie’s villain, Igor Sargoza (Robert Barrat, with a bad Russian accent and worse Leninesque goatee), who shoots down Peter’s plane. There’s a crash landing but no fire. Bandaged and awaiting greater medical attention, Peter pleads with his sister to complete his mission: something about getting an amulet to friends in San Francisco. “Whoever has that amulet can either help or rob China,” he says. “I gave Hoy Long my word that China would not be robbed.”

Hoy Long? Yeah, we never see him.

Passport problems

Later we find out it’s half an amulet, and someone in San Francisco has the other half, and … you know the rest. It’s such a hoary premise that when our hero, newspaper reporter Johnny McGinty (James Dunn), hears about it, he says that it’s like something out of the comics. It’s the screenwriters mocking their industry. Or themselves.

Later we find out it’s half an amulet, and someone in San Francisco has the other half, and … you know the rest. It’s such a hoary premise that when our hero, newspaper reporter Johnny McGinty (James Dunn), hears about it, he says that it’s like something out of the comics. It’s the screenwriters mocking their industry. Or themselves.

Anyway, that’s why Sargoza shot down Peter. And why he follows Irene to Shanghai. He wants the amulet, too. Which begs the question why he shot down Peter in the first place. Isn’t that risking the thing he’s after? Or is the amulet fireproof?

In Shanghai, Irene and McGinty meet when he fights off the men attacking her, then again at the Café Hotel, since, in a helluva coincidence, he’s friends with Howard Barclay (Ralph Morgan), the very man Peter told her to seek out if she ran into trouble. Her trouble? She didn’t have a passport.

She: Do I have to have a passport even for an evacuation?

We also get a semi-creepy scene in the hotel room when the three leads meet up:

Barclay: Would you believe I used to dangle her on my knee when she was a mere infant?

McGinty: Mmm. That’d be alright about now.

There’s a secondary villain, too, Yokahama, played by Paul Sutton in yellowface, and our heroes are captured, released, captured, escape, etc. Much of the movie has a cheap, movie-serial feel to it, and much of the action involves where to hide the amulet: first in McGinty’s camera, then in an incense burner. Except, oh no, that’s an explosive device that kills Sargoza. So much for the amulet. Except, oh phew, Barclay never put it there. He still has it. And he gives it to Irene and McGinty as they prepare to sail to America. But … without him? He’s not going?

Believe me, Johnny, there’s nothing in the world I’d like more. It’s been a long time since I’ve seen the Statue of Liberty. In fact, it’s a long time since I’ve seen … liberty of any kind.

And that’s that.

Everything about the movie has a sad defeated air. Everyone seems to have started out in better places and wound up here.

The other Warner

The movie was made by Franklyn Warner Productions, which was responsible for seven cheapies between 1938 and 1940. Three of them, including this one, were directed by Charles Lamont, who directed 87 features in his day. He started out in silent comedies with Mack Sennett, then went on to do Donald O’Connor teen flicks, the Ma and Pa Kettle series, and a few latter Abbott and Costellos. Apparently he’s also been credited with the discovery of Shirley Temple. The girl, not the drink.

As for our boy? We only see Edward Woods in the first 10 minutes. After he sends sis on the mission, Sargoza shows up, demands the amulet, searches him, and then goes to the Chinese orphans standing in the window. He asks them if the girl got the amulet. One of the kids replies, “I saw nothing. Nothing,” like an ur-Sgt. Schultz. That made me smile.

Sargoza figures it out anyway. “Girl was here,” he says to Peter. “Did you give to her? Did you?”

Peter’s answer is silence. And that’s the last time we ever saw Edward Woods on a movie screen.

Tuesday October 11, 2022

Movie Review: Hot Saturday (1932)

First starring role for some guy named Grant, but most newspaper ads touted Carroll.

WARNING: SPOILERS

“He seems like a fine fellow.”

That’s Cary Grant’s talking about Randolph Scott’s character, to whom he might lose the leading lady, Nancy Carroll, in “Hot Saturday,” directed by William A. Seiter. Since in real life Grant and Scott became housemates shortly thereafter and for much of the 1930s, with the 21st-century assumption that they were longtime lovers, ironies abound.

“No A-name draw in its cast.”

That was Variety’s take on “Hot Saturday,” which was the first starring role for Grant, and for which Scott, who shows up more than a third of the way through, is third-billed. Considering what both men—particularly Grant—became, ironies abound.

Roaring ’30s

It’s an odd little film—an adaptation of a 1926 novel but set in July 1932 as if the Great Depression wasn’t happening and people weren’t suffering. Its concerns are ’20s concerns: young people in roadsters, free-spirited women and the ruin small-town gossip can bring.

It’s set in the town of Marysville, in the state of wherever, and Ruth (Carroll) is the cute little flapper who works at the bank to whom all the men flit and flirt—including Archie (Grady Sutton), a fat bank teller who’s apparently all hands but who seems gay, and Conny Billop (fourth-billed Edward Woods), the reedy-voiced, hair-combing BMOC. In finally landing the date with Ruth, he also gets to say the title line: “Shall we we make a hot Saturday of it?” And we know what Gene Cousineau says about title lines.

Into this picturesque berg, which a title graphic tells us has “one bank, two fire engines, four street cars, and a busy telephone exchange,” comes wealthy playboy Romer Sheffield (Grant), who scandalizes the community by apparently living in sin with Camille Renault (Rita La Roy). I assumed we’d get some innocent explanation to shame the gossips—she’s his sister, etc.—but this is pre-code, and, yep, apparently they are living together. But ol’ Romer’s like every other boy in town and has an eye for Ruth. He even goes into the bank to flirt with Ruth, leaving Camille to stew and steam in the car. The movie treats this as Camille getting her just desserts but it’s rather caddish behavior, and soon Camille is off to warmer climates. “Good,” Romer says, “she’ll probably get a nice coat of tan.” A nice coat of tan. Never heard it said that way before.

When Romer gleans Conny has Ruth locked up for Saturday night, he invites all the kids over to his lakeside estate for an afternoon party, then horns in on Conny’s time. He takes Ruth for a long walk along the lake, and by the time they return most everyone is gone, and now it’s Conny’s turn to stew and steam. At the lakeshore dance hall, Conny rents a boat, makes a pass at Ruth, is rebuffed, then motors them into a private cove to attempt worse. When Ruth escapes onto the shore, Conny abandons her there. She is forced to walk back to Romer’s place. Unlike Conny (and Archie, and…), Romer isn’t all hands. He’s calm and understanding—handsomely fixing her a drink and listening to her travails. He’s basically the perfect gay boyfriend—the man from dream city.

When Romer gleans Conny has Ruth locked up for Saturday night, he invites all the kids over to his lakeside estate for an afternoon party, then horns in on Conny’s time. He takes Ruth for a long walk along the lake, and by the time they return most everyone is gone, and now it’s Conny’s turn to stew and steam. At the lakeshore dance hall, Conny rents a boat, makes a pass at Ruth, is rebuffed, then motors them into a private cove to attempt worse. When Ruth escapes onto the shore, Conny abandons her there. She is forced to walk back to Romer’s place. Unlike Conny (and Archie, and…), Romer isn’t all hands. He’s calm and understanding—handsomely fixing her a drink and listening to her travails. He’s basically the perfect gay boyfriend—the man from dream city.

So who gets in trouble for Conny's loutishness? Ruth, of course. Her rival, Eva (Lilian Bond), sees her being driven home very, very late by Romer’s chauffeur, Conny lies about what happened, and soon the gossip mill is churning about her and Romer. Within 24 hours…

- Two neighbor ladies close the window to her

- Two bank customers snub her

- The Women’s Social League kicks her out

- She's fired

It’s very “The Trial,” isn’t it? Someone must have traduced Ruth B., for without having done anything wrong… Except her mother (Jane Darwell, playing awful, well) thinks she has done something wrong—partying the way she does; hanging with the crowd. Her father, whom everyone calls “Senator,” is calmer and more understanding.

Ruth not so much. She panics. Feeling sullied and trapped, she looks for a way out. Hey, a family friend, Bill Fadden (Scott), has recently returned to town to do a geologic survey for an oil company, and he’s always liked her. So she runs to see him—through a downpour, gets lost, collapses, and he has to rescue her. He also has to remove her wet clothes (off-screen) and put her under a heavy blanket with just those bare shoulders showing. But he’s aw-shucks about it, and looks like Randolph Scott, so it’s cool.

Anyway, the town, or at least Eva and Conny, are not done with her. Ruth and Bill have an engagement party to which they invite all the awful town gossips, including Eva and Conny, and to which Eva and Conny invite ol’ Romer. It's a scheme, see? Since he’s there, everyone talks, Bill overhears the rumors and is scandalized. He all but calls Ruth a whore. Elsewhere, though, the tide is turning. Everyone thinks Eva and Conny were pretty low inviting Romer.

So which gay guy gets her in the end? The perfect gay boyfriend, of course. He’s top-billed. He was just beginning to be Cary Grant but he was still Cary Grant.

Seventh-billed

A few notes.

At Romer’s, there’s an Asian bartender, Archie speaks to him in pidgin English, he responds with the Queen’s version, and Archie all but goes “Whaaaa?” to the camera. So they were doing that bit back then.

Listerine is referenced. So is Marlene Dietrich, a Paramount star with whom Grant co-starred the year before. The script ain't much, but I like this phone conversation Ruth has with a customer as Romer waits in the wings to talk:

Yes, Mr. Smith. The balance is correct. Perhaps you failed to deduct the government tax. … Yes, there's a two-cent tax on every check you write. … Oh no, no. Not just for Democrats. The Republicans have to pay it, too.

You have to feel for Edward Woods. Two years earlier, he was tapped to star in “The Public Enemy” but lost the role to James Cagney. Here, struggling to stay on, he loses the girl to Cary Grant. Someone should’ve let him know both actors would wind up kind of iconic. Even today he gets no respect. I don’t know who chooses IMDb avatars for dead actors, but Woods’ image isn't his face but a photo of “Ted Lewis on Broadway,” with, in the right-most third, a poster for this movie: “Hot Saturday.” His photo on the poster is looking up at Nancy Carroll. Despite being fourth-billed, he’s not even mentioned among the six listed actors.

Friday October 07, 2022

Movie Review: City Streets (1931)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Here’s the three-act structure in a nutshell:

- C’mon, join my Dad’s mob!

- Oh no, why did you join my Dad’s mob?

- Oh my god, don’t fight my Dad’s mob. They’ll kill you!

If you were pitching it today, you’d say it’s “Sergeant York” meets “Little Caesar.” A nice-guy, sharpshootin’ country boy who works at the county fair and is known simply as The Kid (Gary Cooper), is dating the daughter of a prohibition gangster, Nan (Sylvia Sidney), who thinks the beer racket is just fine and wants her boyfriend to join up. He’s not interested.

“You’ll never do a day’s time,” she insists. “Trust Pop. You play ball and the mob won’t let you down.”

So: You can’t trust Pop and the mob will let you down. Oh, and you’ll do time. Or she will.

Good with a gun in the first act

Despite all that, there’s real artistry in the early going, and I guess the credit goes to director Rouben Mamoulian, whom I knew little about, but whose movies are in the directors section at Scarecrow Video—meaning he’s considered something of an auteur. Though his name sounds vaguely French, he’s Armenian, born in 1897 in the old Russian empire, then moved to England, then to the U.S. in the 1920s.

Despite all that, there’s real artistry in the early going, and I guess the credit goes to director Rouben Mamoulian, whom I knew little about, but whose movies are in the directors section at Scarecrow Video—meaning he’s considered something of an auteur. Though his name sounds vaguely French, he’s Armenian, born in 1897 in the old Russian empire, then moved to England, then to the U.S. in the 1920s.

Early on, involved in nefarious activity, Pop drives by and winks at Nan. She winks back. Then we get a straight-on shot of her winking. Turns out she’s now at a shooting gallery at a fair, taking aim at the targets … and missing. Everyone’s missing. They’re all no good. And one older gentleman takes aim across Nan until she takes the rifle out of his hand. “Hey, look out!” she says. Because he’s almost going to hit the guy in the white hat running the stand. At which point, we get a close up of the white hat from behind. And the wearer of the white hat turns around with a little cigarette in his mouth and smiles right at the camera. It’s Gary Cooper.

What a great fucking movie-star intro. Put it up there with Rick in “Casablanca” and Jack Sparrow in “Pirates of the Caribbean.” And dozens I'm forgetting.

You know that whole “Find someone who looks at you” meme? Well, find someone who looks at you the way Sylvia Sidney looks at Gary Cooper in this movie. It’s almost like there’s a little electric current running through her, she’s so giddy with love. At the same time, their early conversation feels natural—during the funhouse mirror scene, and with the hot dogs, and some part of the beach scene. It almost feels adlibbed. Was it? Maybe that’s just good acting and directing.

Again, she wants Kid to joins Dad’s mob but he’s no way. Then mob boss Big Fella (Paul Lukas) orders Pop to kill their colleague, Blackie the bootlegger (Stanley Fields), over a girl. He does, then passes the gun onto Nan; but before she can dump it in the river, she’s caught by the cops, charged, winds up in prison. And where’s the mob? Nowhere.

But just as she gets disillusioned with Dad’s work, Kid is convinced to join up. Oddly, his sharp-shooting ability never comes into play. That feels like a missed opportunity. We see him on the passenger side of a beer truck, urging the driver to ram a blockade, and whooping it up when he does. Then he’s visiting Nan in prison wearing that 1930s gangster staple, a long coat with a fur collar. She’s so happy to see him she doesn’t take in the coat until about a minute later. They argue, kinda. Once again she’s urging him in a direction he doesn’t take, but this time it’s the exact opposite of her first-act direction. Love that.

The third act isn’t as good because it doesn’t follow from what’s happening; it adds to. When Nan gets out, the Big Fella suddenly has a thing for her. It’s out of nowhere. The movie is basically thesis/ antithesis/ 11th-hour addition.

Worried about Kid, Nan tries to take on Big Fella herself, with a little gun in her purse, but he senses the weight and takes it from her. Then he tries to take more from her. She’s only saved because his previous moll, Agnes (Wynne Gibson), who’s been told to scram, can’t bear to lose the Big Fella, doubles back, and shoots him. Now it becomes a kind of Whodunnit, with Kid trying to prove Nan’s innocence to the other gangsters. He doesn’t really, just takes three of them for a ride and leaves them to walk back home in the morning light. Meanwhile, another gang member finds Agnes’ suitcase, meaning Big Fella did tell her to scram, meaning she lied. Meaning she did it.

Morning light

This was Sylvia Sidney’s first starring role—it was supposed to be Clara Bow—and I’m sure she was a revelation. Cooper does his aw-shucks thing to perfection, and the two have great chemistry. I feel like Lukas as Big Fella is miscast—not gangster enough—while Guy Kibbee, usually so reliable at Warner Bros., overacts for this Paramount production: broadly smiling with his eyes so wide they practically pop out of his head.

Remember when you were young and you’d stay up all night with friends, partying maybe, or just hanging out, maybe expecting something to happen and usually not getting it, and in the morning light everything would just kind of dissolve in weary fashion? That’s kind of what the ending of this movie feels like. It’s not bad, it just doesn’t tie everything together. And maybe that’s nice for a change. It’s just the two stars, in the morning light, safe again, driving back to the city in his 1929 Lincoln, with the POSCL MOTOR CAR RADIO on, as birds take flight.

SLIDESHOW

Saturday September 24, 2022

Movie Review: She Had to Say Yes (1933)

“I suppose it's just a matter of choosing the lesser evil.”

WARNING: SPOILERS

I’d love to watch this with a group of twentysomethings just to see their heads explode.

First there’s the title, titillating back then, a lawsuit waiting to happen now, and not even true in terms of the story. Loretta Young didn’t have to say yes, and she didn’t say yes. And anyway there’s a better title—which I’ll get to by and by.

Please don’t

In the midst of the Great Depression, a New York clothing company run by Sol Glass (Ferdinand Gottschalk) uses “customer girls” to entertain out-of-town buyers. You’ve got to do what you can to survive, right? The problem is Sol is losing business because his girls are “worn-out gold diggers.”

Let’s pause for a moment over the term “gold digger.” The original meaning was literal, of course, a 49er in the 1840s, say; but in the 1920s it began to mean a woman, usually unmarried, often a chorus girl, who uses her wiles to get men to part with their dough. It was the title of a silent movie in 1923, and became the title of a series of musicals at Warner Bros.: Gold Diggers of 1933, 1935, 1937. Here’s a newspaper.com chart of how often the term shows up in American newspapers from 1910 to 1950:

1933 was the peak year, with 21,201 references.

The problem with Sol’s girls isn't that they’re gold diggers; it’s that they’re bad gold diggers. A rep from “Beau Marche” (nice) is locked out of his hotel room in his underwear. That’s a gold digger? Not from Sol’s perspective, since he loses the dude’s business. Which is the point he makes at an emergency meeting: “Gentlemen, our customers must be entertained but never insulted.”

One manager, after a failed attempt at the high road (getting rid of customer girls altogether), says their girls aren’t just “worn out”; they’re the same. The out-of-town buyers have seen them before. Which is when up-and-comer Tommy Nelson (Regis Toomey) gets an idea: Why not use the girls from the steno pool? They’re new, cute, “and they got brains that work standing up, too.”

And hey, he just happens to be dating one of them: Flo (Loretta Young). And she’s willing to help the team, and big buyer Luther Haines (Hugh Herbert of the high-pitched laugh) certainly has an eye for her, but no, Tommy loves her too much for that. Tommy may seem like a crass jerk but he keeps doing the right thing by her.

Until he doesn’t. Then he’s cheating on her with Birdie (Suzanne Kilborn). And when a big shot, Daniel Drew (Lyle Talbot), comes to town, hey, could Flo show him around?

Talbot’s the leading man, so we assume he’ll be a nicer guy than Tommy. Not really. He puts the DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door while plying Flo with booze.

He: You’re a funny little thing. C’mere, will you—

She: Oh, please don’t.

And later:

He: Yours is the penalty for being so lovely.

She: I suppose yours is the privilege for being so important.

And even later:

She: I hate being pawed.

He: Maybe you’ve never been pawed properly.

Reminder: This is the movie’s leading man.

With the help of brassy friend Maizee (Winnie Lightner, the best thing in the film), Flo eventually learns Tommy is cheating on her and breaks up with him. Then Tommy shows up drunk and mashes her: “My money’s as good as theirs! Now you just close your eyes and pretend I’m a buyer.”

Seriously, half the film is Loretta Young politely and/or tearfully fending off the amorous advances of jerks. And when she tells Sol she won’t do the “customer girl” thing anymore, he insists, so she quits. She tells Maizee that she’s quitting men, too. But as soon as Danny “You’ve Never Been Pawed Properly” Drew calls, she’s back in the game.

It’s an awkward game. One moment he’s all over her, the next he’s professing his love. The latter scenes are actually worse. They visit the 86th floor of the newly opened Empire State Building, he says he feels on top of the world, then adds, “With you by my side, I’d get the same feeling in the subway.” Uck. She looks over the edge and says it makes her dizzy, and he looks at her and says the same. Uck.

And then he pimps her out! Kinda sorta. The guy holding up his high-priced merger is Luther Haines of the high-pitched giggle; and even though it makes her eyes dim with sadness, Danny asks her to use her connection to get to Haines. I guess she assumes the worst? Because she winds up using her beauty, and Haines’ lechery, to trick him into the merger. And then Danny assumes the worst—that she slept with Haines? Because he drives her to an out-of-the-way house and tries to rape her.

How long did you think I was going to fall for this wide-eyed stuff? Me with a reputation a mile long. And I fall as though I’d never met a little tramp before.

Reminder: This is the movie’s leading man.

Hey, guess who’s outside the house? Tommy! The other jerk. He’s been following her because he needs to know the age-old idiot-man question—saint or whore?—and for a moment he believes the former again. Then her purse spills, he sees the $1,000 check for the merger deal, and assumes it was for, you know, whoring. Which is when Danny comes to her rescue. He can accuse her of whoring but no one else can!

Of course, silly!

That’s pretty much the movie: Men force women to use their sexual allure to get money from other men, then accuse the women of being tramps.

I was curious how it would end. Would Flo just declare her independence? Could she and Maizee take to the road like an ur-Thelma and Louise? Of course not. Either way, she couldn’t wind up with Danny. Not after all he said and did. They wouldn’t force that on us, would they?

They would. Mel Gibson’s Jesus was less tortured this dialogue:

She: Oh, why doesn’t a woman ever get a break? You treat us like the dirt under your feet—first Tommy, then you, and now Tommy again.

He: I guess I’m just thick, darling. I love ya, I really love ya. If I didn’t I wouldn’t have said those terrible things to you. … Will you forget all this, and forgive me, and marry me? I’m terribly sorry.

She: I suppose it’s just a matter of choosing the lesser evil.

He: Then you’ll marry me?

She: Of course, silly!

That's my suggested title: “The Lesser Evil.” Both of you are jerks, he’s a bigger one, so I guess I’ll live with you forever. Imagine poor Maizee when she hears the news.

The screenwriters (Rian James and Don Mullaly) and directors (George Amy and Busby Berkeley) manage to do one thing right. After the above, Danny says he needs to get his hat and coat, Flo whispers in his ear, and he picks her up and takes her inside. Fade out. We never find out what she says. That’s good—both in a “Lost in Translation” way and because we don't have to hear any more dialogue.

Saturday September 10, 2022

Movie Review: The Criminal Code (1930)

WARNING: SPOILERS

My favorite moment is a line reading from Boris Karloff.

Three men are in a jail cell and the youngest, Robert Graham (Philips Holmes), gets hysterical after he receives word that—shades of “White Heat”—his mother has died. A guard, Captain Gleason (DeWitt Jennings), who is not so much sadistic as just a big fat jerk, wants to know what the commotion is. Jim (Otto Hoffman), the old hand, says they got the kid under control but Gleason isn’t satisfied. “No con under me can yowl that way and throw this pen into a panic—kick him over here.” At which point the camera focuses on Galloway (Karloff), who says, slowly and plainly, “Come in and get him.”

It’s not an overt threat, it’s just filled with underlying menace. I was like: Holy shit.

Earlier, before the telegram, as the other two talk, Galloway is mostly silent, reading his newspaper. Then we get his back story. He’d been sentenced to 20 years, got out after eight, and went to a speakeasy to wash the taste of the place out of his mouth. But he was spotted, ratted on, and sent back for the remaining 12. “Twelve years, for one lousy glass of beer,” he says. “The guy that squealed is in here, too. I’ve got an appointment with him—and 12 years to keep it.”

Earlier, before the telegram, as the other two talk, Galloway is mostly silent, reading his newspaper. Then we get his back story. He’d been sentenced to 20 years, got out after eight, and went to a speakeasy to wash the taste of the place out of his mouth. But he was spotted, ratted on, and sent back for the remaining 12. “Twelve years, for one lousy glass of beer,” he says. “The guy that squealed is in here, too. I’ve got an appointment with him—and 12 years to keep it.”

Gleason is the guy who squealed.

All of which made me think that even if Karloff didn’t become famous for “Frankenstein,” we still would’ve heard of him. Who knows, maybe “Frankenstein” unfairly stuck him in a genre, horror, that tends to the cheesy and slapdash.

A man must have a code

Karloff isn’t the hero of “The Criminal Code” but might as well be. He’s the guy who enforces the second kind of criminal code.

Yes, the title has a double meaning. To the lawmen, it’s the code against criminals—to throw the book at them, basically. To the prisoners, it’s the code of criminals, a code of honor, which begins and ends with: Don’t snitch. Galloway is the one who embodies this latter aspect. He kills the cowardly prison snitch, Runch (Clark Marshall), going after him slowly and stiff-legged, almost like a precursor to “Frankenstein”; and when Graham gets solitary for not snitching on the killing, and may get worse when other cons send him a knife, it’s Galloway to the rescue. “That kid don’t take no rap for me,” he says. “I’m going to keep an appointment.” The one with Gleason.

The ostensible hero, though, is Mark Brady (Walter Huston), who begins the movie as a crusading district attorney, unsuccessfully runs for governor, and is then appointed prison warden. Huston gets one good scene. He prosecuted a bunch of the cons himself, they’re plotting against him, and when they see him in a window they start yammering. Just a lot of noise. So Brady goes down to the yard himself. Outside, he lights a cigar, and walks into a sea of parting cons. The yammering stops. He stares straight at them, and then at one con in particular. “Hello, Tex.” Long pause. Tex bends his head. “Hi, Mr. Brady.” And that’s that. He’s won the day. I don’t buy the scene but Huston sells it well.

I just didn’t like Brady. He’s the one who first annunciates the lawman’s version of the criminal code. The movie opens with an accidental murder by Graham (nightclub, jerk, bottle), and, looking at the evidence, Brady talks about how he could get the kid off if he were his defense lawyer. “It’s just a rotten break, that’s all,” he says. But when the kid’s out-of-his-element attorney suggests 10 years on a manslaughter charge is too much, Brady jumps down his throat:

Good lord, man, what do you want? There’s a boy lying on a slab in the morgue. That’s a big piece out of his life—all of it. Somebody’s got to pay for that! An eye for an eye. That’s the basis and foundation of the criminal code. Somebody’s got to pay!

These words are repeated throughout the film. Galloway uses similar ones when talking about Runch and the other criminal code: “He squealed, turned on his pals, and a man’s dead. Somebody’s got to pay for that.” Then when the kid is left holding the bag for Runch’s death, and Brady suspects his innocence and is trying to sweat it out of him, Brady’s original words are tossed back at him by the state’s attorney (Russell Hopton), who wants someone charged ASAP:

A man’s dead and somebody’s got to pay! An eye for an eye! That’s the basis and foundation of our criminal code, Mr. Brady.

Not a bad structure: the first-act criminal code puts a poor kid in prison, the second-act criminal code leads to the death of a prison snitch—for which that same kid might unfairly have to pay if the third-act criminal code is pushed forward. But it’s not. When the state’s attorney leaves his office, Brady lights a cigar, looks after him, and says “fathead.” He says it twice. One gets the feeling the second “fathead” is for his earlier self—the one without empathy.

There’s also a romance between Graham and the warden’s daughter (Constance Cummings, making her film debut), which isn’t bad, considering it’s a romance between a con and the warden’s daughter.

How does it all play out? As Brady sweats Graham, one con (Andy Devine!) sends Graham a knife, Galloway says enough of that and gets himself tossed in the hole, too. There, after a failed shootout, he throws the gun out but grabs the kid’s knife and uses it to kill Gleason; then he’s killed himself. The warden then reunites his daughter with Graham—without even a shower for the kid—and they hug and kiss and profess their love, while Brady repeats the line he told Graham before sending him away: “That’s the way things break sometimes.”

Right. At this point, I already miss Karloff.

The death of Runch: Frankenstein before Frankenstein.

Early QT

The movie’s got a good opening anyway. Two detectives are playing pinochle at the station, a call comes in about a fight at Spelvin’s Café, and they’re told to get going. They do, but their minds are hardly on the work:

Cop 1: By my rules you owe me 42 cents.

Cop 2: That’s you all over: arbitrary.

Cop 1: I don’t know what arbitrary means but you still owe me 42 cents!

Dudes on a case talking about everything but the case. It’s like Tarantino 60 years before Tarantino.

I also like an early scene in the D.A.’s office when the girl the fight/murder was over, sitting next to Brady’s desk, inches her skirt just above the knee to distract Brady. “Pull down the shade,” he says to her.

Howard Hawks directed this before he became Howard Hawks. (His next film was “Scarface.”) Seton I. Miller was one of two men adapting it (from a stage play by Martin Flavin), while James Wong Howe was one of two cinematographers on the project. Back then he was sometimes credited as James Howe but this is the only time his name was misspelled: “James How.”

Tuesday September 06, 2022

Movie Review: Barbary Coast (1935)

WARNING: SPOIILERS

Didn’t a famous director once say that the drama on a movie set is often more interesting than the drama in the movie? I thought it was Hitchcock, and I thought it led to Truffaut’s “Day for Night,” but I’m not not finding any on that online. Maybe I’m looking in the wrong place.

Whoever said it, you could apply it to “Barbary Coast.” The story in the movie is silly—dictated by its time and stars. A hifalutin dame, Mary Rutledge (Miriam Hopkins), soon nicknamed “Swan,” is set to land in gold-mad, 1850s San Francisco, the notorious Barbary Coast, to be the bride of a man she’d never met: Dan Morgan. Except Mr. Morgan, he dead. So she waits for the alpha dog to emerge. That’s Luis Chamalis (Edward G. Robinson), who runs the Bella Donna, a saloon/casino that cheats the prospectors out of their scraped-together findings. Swan, dressed in frilly white, does the same, while putting off the amorous advances of Luis. Then she falls in love with a tall, poetry-spouting prospector, Jim Carmichael (Joel McCrea), but lies to him about her background. When he discovers the truth—just before the boat back to NYC and his beloved Gramercy Park—he gambles his earnings, she cheats him of them, and they’re both like “Fine!” But in the final act—as citizens form vigilante squads and string up the gangsters—they find love again and are ready to leave the place. But no, Luis won't have it, and he wings Jim and is about to kill him when Mary convinces him to let them go so they can blah blah. And he surrenders himself to the mob to die. And the lovers blah blah.

Yeah, blah. But behind the scenes? Wow.

In his autobiography, Robinson writes admiringly of Jean Arthur, his previous co-star in “The Whole Town’s Talking”: “She was whimsical without being silly, unique without being nutty, a theatrical personality who was an untheatrical person. She was a delight to work with and to know.”

In his autobiography, Robinson writes admiringly of Jean Arthur, his previous co-star in “The Whole Town’s Talking”: “She was whimsical without being silly, unique without being nutty, a theatrical personality who was an untheatrical person. She was a delight to work with and to know.”

Next graph, he lowers the boom: “Miriam Hopkins, on the other hand, was a horror.”

He enumerates the problems. She was always late, changed dialogue, missed her marks, tried to upstage her co-stars, particularly Robinson, and was generally theatrical and haughty. For her closeups, Robinson read with her; for his, she couldn’t be bothered and the chore went to a script girl. In one scene he had to slap her, and he wanted to rehearse it so it would look real and not hurt. She wanted it once and done, and told him to slap her for real. “I slapped her so you could hear it all over the set,” he wrote. “And the cast and crew burst into applause.” His implication is everyone else was sick of her, too, but who knows? Maybe they admired her dedication to the craft? Or that it was one and done?

Such tensions, I'm sure, aren't untypical. But this is what I’m getting at:

In addition, the set of Barbary Coast was highly politicized. … [screenwriters] Hecht and MacArthur were liberals; Howard Hawks, Miriam Hopkins, Joel McCrea Walter Brennan and Harry Carey were not liberals. … F.D.R. was still in his first term, and anti-administration forces were calling the New Deal un-American, Bolshevik, communist and socialist. These inflammatory points of view were constantly being aired on the set …The wealthy, the celebrated, the successful (and, realize, I could now count myself among them), saw F.D.R. as an enemy trying to change the fundamental fabric of the Republic. On the other hand, we saw him as a man trying to save capitalism by dealing with the fundamental inequities in the nation.

Robinson doesn’t go into how this politicization manifested itself—probably with the usual arguments—but plus ca change, right? These forces are still trying to undo the latest progressive step: Obamacare, Obergefell, abortion. Some are still trying to undo the New Deal.

And just think of the relevance to Robinson. Nine years later, Hawks helped found, and Brennan became a prominent member of, The Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals, a right-wing Hollywood org that worked in tandem with Hoover’s FBI and HUAC to help create the circumstances that led to the Hollywood Blacklist, which curtailed Robinson’s career. A liberal, he was attacked for speaking out against Fascism but not Communism, and was forced to appear before HUAC and trout out a confessional article “How the Reds made a Sucker Out of Me” for American Legion Magazine in 1952. He had to go hat-in-hand to Ward Fucking Bond to get work again. And even then it was B pictures.

That’s your story. “Barbary Coast” is bullshit in comparison.

White woman

I first heard the phrase “Barbary Coast” in 1975 when William Shatner starred in a short-lived TV series by that name. I don’t think I watched it much, despite Capt. Kirk. It didn’t zip to me. It was stuck in the mud.

For some reason, in the mid-1930s, we got an influx of movies set there: this one (released Sept. 1935), Cagney’s “Frisco Kid” (Nov. 1935), and Clark Gable in “San Francisco” (June 1936), which updates things to the 1906 earthquake, and which was a runaway smash hit. So was it just that Hollywood tendency to do what everyone else is doing? Or a novel way to use modern gangster-actors in non-modern settings? Maybe the production code growing teeth in 1934 made producers look toward, you know, “simpler times.”

The “W” word is dropped early: white. Mary Rutledge creates a sensation because she’s basically the first white woman in San Francisco. When she’s rowed ashore in the fog by journalist Col. Marcus Aurelius Cobb (Frank Craven) and Old Atrocity (Brennan), we get this exchange:

Man: Who ya got there?

Old Atrocity: A white woman!

Man: Ah, yer lyin’!

Old Atrocity: No, I ain’t! She’s a New York white woman. Whiter than a hen’s egg!

Man: Whooo!

It’s New Year’s Eve, some white men are having fun cutting the pigtails off of Chinamen (as one does), and Mary and Luis toast each other. The next morning a deal is struck in the vague way of code movies. He offers protection, a position, and a way to make a mint. And she offers? I guess her plumage at the roulette wheel. In any non-code movie, he would also get her, i.e., sex, but this is code, so no. Plus it’s Robinson. He never gets the girl. He’s always desperately on the outside of that exchange.

McCrea doesn’t show up until about 40 minutes in. He’s good. He should’ve had more scenes with Robinson because they’re so opposite: tall, handsome, and an easy-going mark, vs. short, conniving, and having zero luck with the ladies. Could’ve done without the bad poetry, but I guess Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, and probably Columbia, thought it high-class.

The movie never quite coalesces or resonates. In an early scene, the men in town carry the newly arrived Mary across the street so she doesn’t get mud on her dress, and unfortunately the movie does the same. It wants her innocent and mud-free when she’s more cutthroat than that. For half the film, she’s bilking the schmucks.

Older man

There’s also a subplot with Mary’s original protector, Col. Cobb, who decides to publish a newspaper in town. But when he tries to get involved with progressive reform, he’s killed by Luis’ muscle, Knuckles Jacoby (Brian Donlevy). I remember thinking, “Sure, Donlevy again,” but this was actually his first such role. Before this, he’d just been in silents and shorts. A string of 1935 flicks led to a long career expertly playing heavies.

The actor who plays Cobb, Frank Craven, was an old theater friend of Robinson’s, and, despite being a rock-ribbed Republican, the two had a good time reminiscing. But Robinson noticed Craven had gotten older, and it made him realize that so had he. He was 41 now, with more past than future, and “I didn’t like it.” That said, a few years later, Craven got his biggest role yet, as Stage Manager in the original Broadway production of “Our Town,” a role he played in the movie version, too. So I guess it’s never too late.

Amazing with all the legendary talent in the room—Hecht, MacArthur, Hawks, etc., produced by Samuel Goldwyn, with costumes by Omar Kiam—that this was the result. “Frisco Kid” was much better, and it wasn’t particularly good.

Saturday July 23, 2022

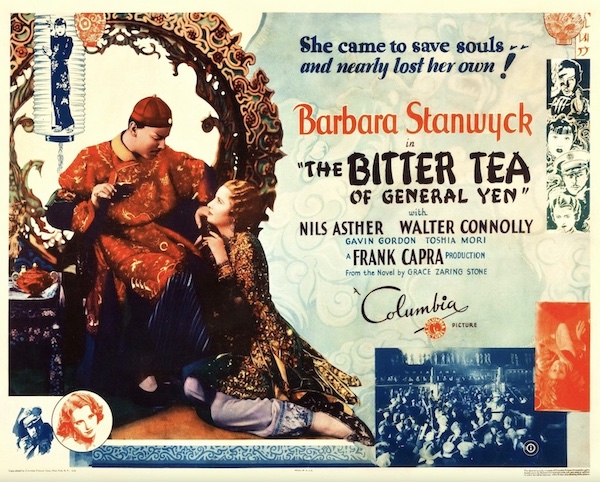

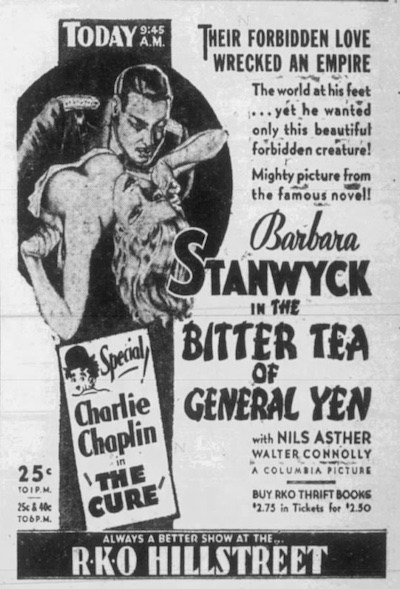

Movie Review: The Bitter Tea of General Yen (1932)

WARNING: SPOILERS

What’s startling isn’t the racism (c’mon) but the fact that the movie sometimes moves beyond the racism. I mean, it’s a 1932 love story between a white woman and a Chinese man. And sure, the Chinese man is played by a Scandinavian actor, Nils Asther (born Denmark, raised Sweden), but still: It’s a 1932 love story between a white woman and a Chinese man.

Is there another similar movie from this period? The reverse certainly: Asian woman, white dude. White dudes were making these movies, after all. That's their fantasy. The other is their nightmare.

Although isn’t Valentino’s “The Sheik” similar? A warlord is amused by, then smitten with, a feisty white woman, abducts her, holds her prisoner without forcing himself upon her, and gradually they fall in love. Both movies were based upon novels by women, too: Edith Maude Hull there, Grace Zaring Stone here. One difference: At the end of “The Sheik,” he reveals he’s not really an Arab but British/Spanish; that means the couple can stay together. Here, he is in fact Chinese. That means he has to die.

Even removing race from the equation, I found “Bitter Tea” kind of fascinating. At bottom, it’s about a brutal leader who falls in love, follows the woman’s lead toward mercy, and then loses everything as a result. It feels like a lesson: about what women want the world to be; about what the world really is.

Fu Manchu vs. the Masked Marvel

It begins with the chaos of war, with these titles projected on the screen at various intervals:

- CHINA

- SHANGHAI

- BURNING OF CHAPEI

- REFUGEES

If you don’t know Chapei (I didn’t), it’s a suburb of Shanghai, now spelled Zhabei, and was much in the news in early 1932. (Filming for this began in July of that year.)

Amid the chaos, we get shots of guests arriving in the rain for the wedding of Megan and Bob (Barbara Stanwyck and Gavin Gordon) at the home of Mrs. Jackson (Clara Blandick*). “Everybody in China is here,” the hostess says. “Literally everybody.” Nice to know that people back then didn’t know how to use “literally,” either.

(*If Blandick looks familiar, there’s a good reason: She played Auntie Em in “The Wizard of Oz.” Overall, she has 124 credits—from a 1911 short to a 1951 TV series—and during her career she played an aunt 19 times, including Aunt Polly from “Tom Sawyer” three times in the ’30s alone. She died in 1962, age 85, so maybe had a glimmer that one of the seven movies she made in 1939 was becoming legendary.)

Mrs. Jackson also embodies the casual racism of the time: “They’re all tricky, treacherous and immoral,” she says of the Chinese. “I can’t tell one from another. They’re all Chinamen to me.”

We get something more nuanced, but equally troubling, from Bishop Harkness (Emmett Corrigan):

I’ve spent 50 years in China. And there are times when I think we’re just a lot of persistent ants trying to move a great mountain. Only last month, I learned a terrible lesson. I was telling the story of the crucifixion to some Mongolian tribesmen. Finally, I … I thought I’d touched their hearts. They crept closer to my little platform, their eyes burning with the wonder of their attention. Mongolian bandits, mind you—listening spellbound. But alas, I had misinterpreted their interest in the story. The next caravan of merchants that crossed the Gobi Desert was captured by them and … crucified. [Gasps from his listeners.] That, my friends, is China.

At this point the camera whirls away, almost 180 degrees, and lands on an ancient Chinese face. I suppose you could read this as either “Here’s one of the inscrutable devils!” or “Look at this poor bastard having to listen to this bullshit.” I lean toward the latter. Maybe because the director is Frank Capra, or because the screenplay was written by Edward E. Paramore Jr., who, I believe, leaned left. But mostly because of the way the rest of the movie plays out.

The bride shows up after a rickshaw accident with the titular general, tall and French-speaking, while the groom, a kind of hapless Samaritan, shows up only to say he’s going to leave. He needs to help orphans get out of the line of fire. (A civil war is implied rather than the Japanese one.) To do this he goes to, yes, the titular Gen. Yen, where we get the following exchange:

Bob: I’m sorry to intrude like this, General, but it’s a matter of the utmost importance.

Gen. Yen: Naturally. Everything you do is important.

Such a great, cutting line. And such a nice line-reading from Asther.

Yen, cold-blooded, then dismisses orphans as people without ancestors, and tries to entice the foreigner with “singsong girls”—a new phrase for me, but one which goes back to the 19th century. Basically, they’re Chinese geisha girls. When Yen learns that Bob actually bolted from his wedding for this good deed, the note he writes—which will supposedly help Bob get across nationalist lines—calls him a fool, and the first gang of soldiers he meets mock him accordingly. They laugh at him, steal his car, ogle Megan (she’s with him because: feisty). To get the orphans to safety, they now have to make their way on foot to the train station, where Bob and then Megan are knocked out. When she awakens, she’s in the train car of Gen. Yen, who’s with his concubine Mah-Li (Toshia Mori).

We don’t know it yet, but that’s it for Bob. He lives, but we never see him again. He’s out of the picture.

The rest of the movie is Megan, trying to escape Gen. Yen’s headquarters/estate while slowly succumbing to his charms. At one point, drugged, she has a dream of a rapacious Fu Manchu figure straight out of the pulps, with long claws for fingernails; and then—early superhero alert!—a masked figure appears in the window and beats back the Chinese devil. We assume Yen is Fu Manchu and the hero is Bob, but when the hero takes off his mask it’s Gen. Yen. When Megan wakes up, she’s so, so confused. And intrigued.

Mah-Li, it turns out, has her own lover, and when Megan doesn’t give her away the two become close. Or close-ish. At one point, Mah-Li convinces her to go to a formal dinner, and Megan gets all dolled up for it; then she thinks of kissing Gen. Yen, is shocked by the desire, and takes off the makeup.

At the dinner, we meet Jones (Walter Connolly), Yen’s corrupt but forthright western money man. I love this exchange we get later in the film when Jones realizes Yen is actually interested in Megan.

Jones: Listen, I’ve never interfered in your private affairs before. But don’t forget, this is a white woman.

Gen. Yen: That’s alright. I have no prejudice against the color.

Again: ahead of its time.

Perfumed silence

The merciful thing Megan convinces Yen to do is to spare Mah-Li even though she betrays him. And so Mah-Li betrays him further, sending out a secret message via temple gong to enemy forces, which leads to a daring railroad raid. And there goes all of Yen’s money and influence and power.

At this point he knows he’s dead, and the rest of the movie is his slow death—suicide by poison or opiate, or a combination therein. This is the bitter tea of the title. It goes on too long, to be honest.

I like that the movie, via Jones, rightly blames Megan for Yen’s death:

Well, Miss Davis, you certainly gummed up the prettiest set-up I ever saw. I had visions of making General Yen the biggest thing in China, but you sure queered that beautifully. I hate your insides, Miss Davis, but you’re an American and we’ve got to stick together now…

What great language from Paramore: gummed up, queered, hate your insides.

Stanwyck barely says anything in response, or really for the last 10 minutes of the film. Maybe because there’s nothing to say? She and Jones are on a slow boat away from China, and Jones keeps jawing away: about Yen, about trees, about reincarnation.

The reception the movie received is interesting. Most of the 1932-33 reviews I’m seeing via newspapers.com are positive (though the phrase “perfumed silence” is so overused I get the feeling the critics were cutting and pasting press-agent copy); and when Radio City Music Hall decided to include feature films with its live stage shows in January 1933, “Bitter Tea” was the first one tapped. But it didn’t last. Disinterest or racist backlash? Stanwyck claimed the latter. Who knows? We do know that when Columbia tried to re-release the film in 1950, the Production Code Administration wanted so many cuts Columbia gave up. A reminder that, politically and culturally, we can take giant steps backwards, too.

Monday June 20, 2022

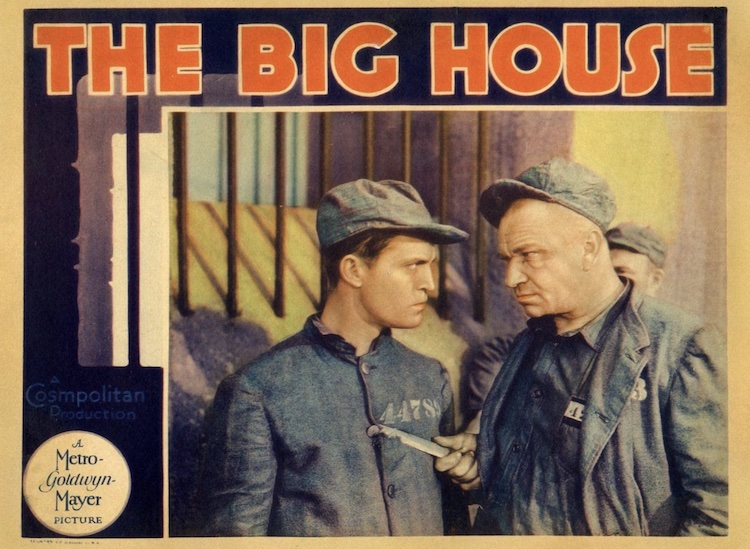

Movie Review: The Big House (1930)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Hollywood’s ur-prison film depicts a system, like in “Les Misérables,” that reduces a man to a number—or a series of numbers. This, for example, is Kent Marlowe (Robert Montgomery):

- 48642

- 265

- 10

That’s his prison number, cell number, and the years he’s serving for vehicular manslaughter.

We first see Kent after the opening credits (shown against the machine-like clomping of prison feet), when a van pulls up to a vast, concrete prison—an obvious matte drawing—and three men get out. Two are guards. The third is Kent and we immediately sympathize with him. He’s clearly out of his element: dazed and scared. He’s surprised that he has to call the guard “sir,” semi-stunned when they take his possessions after frisking him, stunned that his body is no longer his own. I like the moment when the initial guards leave and he watches them go as if he's a kid whose parents have left him at camp.

We get more numbers from the warden (Lewis Stone): 3,000 and 1,800. The latter is the cell accommodations in his prison; the former is how many prisoners they actually have. “They all want to throw people into prison but they don’t want to provide for them after they’re in,” he tells a guard. “You mark my word, Pop, someday we’re going to pay for their shortsightedness.”

The first to pay is Kent.

The early “Les Mis”-like theme.

Boldness cowardice blame

They stack him atop two other prisoners in cell 265. These two just happen to be the toughest men in the yard: Morgan (Chester Morris) and Butch (Wallace Beery).

Even with this open, though, with Kent wholly gaining our sympathy, and Morgan and Butch the tough guys, they becomes the film’s heroes while Kent becomes its villain. A key line comes from the warden:

Remember, this prison does not give a man a yellow streak. But if he has one, it brings it out.

That’s Kent. Early on, a rat named Oliver takes him aside and gives him some advice, and you can see the movie setting itself up. Will Kent be on the side of Oliver the rat, or on the side of Butch and Morgan, cons but decent joes? I assumed the latter. I assumed, hey, it’s Robert Montgomery, he’s handsome and sympathetic, he’ll side with the decent joes. Nope. It’s an interesting twist, given the open. But at this point in his career, Montgomery (Elizabeth’s dad) wasn’t yet a star. He’s actually fourth-billed here, after the warden.

The stars are Morris and Beery, and they’ve got great rapport. Morgan, easy-going and handsome, but with steel in his eyes, is the only one who calls Butch on his bullshit—who’s got so much it’s hard to sort out. At one point, Butch tells Kent he’s the guy who wiped out the Delancey Gang—and he probably did. He also talks about how well he does with the ladies—and maybe he does? He has a repeated phrase when called on his crap: “Who, me?” He’s that ne’er-do-well kid found out, the lovable mug with an “Aw shucks, I didn’t mean to try to kill ya” demeanor. It’s a fine line but Beery walks it like a pro.

There’s a great early scene. In the yard, Butch gets a letter from a girl named Myrtle and begins to read it aloud to the boys. She tells him she misses him, how he’s “it.” Then he leaves off. Amid jeers, he says the rest is just for him and Morgan and they go to their own corner of the yard—where Butch hands Morgan the letter to read to him since he can’t read. Turns out there’s no Myrtle. “If I even knew a dame called Myrtle, I’d kick her teeth out,” he tells Morgan. No, the letter is from a fellow gang member, Tony Loop, who lets him know his mother was sick and now she’s dead. It’s nicely underplayed. Morgan gets Butch to talk about her and he does, a small smile on his face, absent-mindedly running gravel through his hands, about how she was “as big as a minute. And game.”

But the movie doesn’t pretend Butch isn’t also brutal and a cheat. Basically Butch’s boldness causes problems that Kent’s cowardice exacerbates, and somehow Morgan gets the blame.

Example: The guards are searching for Butch’s knife, so in the prison mess he passes it down the line and Kent winds up with it. When they do a cell search, he panics and stashes it among Morgan’s stuff and it’s found. So instead of parole, Morgan gets another year, plus solitary, and vows revenge against Kent. To this end, he breaks out of jail to pursue Kent’s sister, Anne (Leila Hyams), a looker. If that doesn’t make much sense, well, you’re right. Anne was originally supposed to be Kent’s wife, so Morgan would’ve been cuckolding him. But women in preview audiences didn’t want a matinee idol like Chester Morris doing dirty like that, so they reshot scenes to make Anne the sister. It mostly works but it means Morgan’s motivation here is a little odd.

Of course, he falls for her, and she for him, but he’s spotted by a cop (Robert Emmett O’Connor, Paddy Ryan from “Public Enemy”), and sent back to jail. There, we get that boldness-cowardice-blame dynamic again. Butch plots a prison break, Kent snitches, and when it turns violent Morgan is blamed for the snitching. Amid gunfire, and a WWI Army tank(!), our two heroes go gunning for each other. After they're both plugged, they crawl toward each other:

Morgan: Sorry, Butch. Did I get ya?

Butch: I’m on my feet, see?

Morgan: Don’t lie to me.

Butch: Who, me?

Morgan: Yes, you.

A guard then lets Butch know it was Kent—already gunned down—who was the snitch. At this point, the two men should’ve died in each other’s arms. Theirs is the movie’s true love story. Ah, but those women in the preview audience wouldn't like it. So Butch dies, Morgan survives, and is suddenly and nonsensically pardoned. He leaves the prison and into Anne’s arms. Who, him? Yes, him.

I like the penultimate scene, where the warden asks Morgan about his plans. “I thought I’d go to the islands of some new country,“ he says, ”and take up government lands.” That was still a thing back then? To just go to a place and just get land? Oh, to be free, white and 21.

Call and response

The role of Butch was originally intended for Lon Chaney, but he died suddenly in 1930, so Beery, who’d had trouble making the transition to talkies, got the nod. It not only resurrected his career, it supercharged it. He was nominated for an Academy Award for lead actor, losing to George Arliss (“Disraeli”), but a year later he won for “The Champ.” He made a series of popular films with Marie Dressler, starred in many of the early classic MGM ensemble films (“Grand Hotel,” “Dinner at Eight”), and played everyone from Pancho Villa to Long John Silver to P.T. Barnum. During the first four years of Quigley’s Top 10 Box-Office Champions (1932-35), he was one of four stars listed every year. The others were Joan Crawford, Will Rogers and Clark Gable.

“The Big House” was nominated for four Academy Awards and won two, including best writing for Frances Marion, the wife of director George W. Hill, who became the first behind-the-scenes woman to win an Oscar. Apparently she visited a prison to get a sense of what it was like. I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s where the sharp details of the opening scenes come from.

Speaking of: There’s another good numbers scene there that made me do a double-take. Kent is being given his (what turn out to be) ill-fitting prison clothes, and we get a kind of sing-songy call-and-response, as one prison official lets another know the sizes:

- Coat, 36 (coat, 36)

- Underwear, 4 (underwear, 4)

- Pants, 5 (pants, 5)

- Shirt, 16 (shirt, 16)

- Hat, 7 (hat, 7)

A year later, Warner Bros. ripped off this riff in “The Public Enemy” when Tom Powers first gets a suit. It actually makes more sense—and is more effective—here, since it plays into the whole reduction-of-a-man-to-a-number theme. In “Enemy” it’s just a slightly homophobic moment showing Cagney rise.

The Anne angle aside, “Big House” is an amazing early film. There’s a documentary feel to scenes, a power to Beery’s performance, and even a great tracking shot (Morgan visiting Anne at her parents’ house) that demonstrates that not all cameras in early talkies were stagnant.

The star turn: Beery filling a whole prison with the force of his face.

Monday June 13, 2022

Movie Review: King of the Underworld (1939)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This is the movie that Humphrey Bogart made between getting plugged by James Cagney in “Angels with Dirty Faces” and getting plugged by James Cagney in “The Oklahoma Kid,” and for once he gets star billing. Apparently Warner Bros. was punishing its star, Kay Francis, so they took her star away and gave it to Bogie. But she’s the hero. And he still gets plugged.

Lousy title, by the way. Why not “The Napoleon of Crime”? Or “The Gangster and the Lady Doctor”? Why not anything to do with the story?

It's a lousy movie anyway. And short. It’s the old Alvy Singer joke: terrible, and in such small portions.

Doctor’s widow

“Underworld” packs a lot into its 67 minutes. An elder doctor counsels a younger doctor, Niles Nelson (John Eldredge), not to perform a risky operation, since, if you don’t do it, it’s not your fault. (Dude puts the hypocrite into Hippocratic Oath.) He’s ignored and the surgery works. Turns out the patient is a gangster, and the gang leader, Joe Gurney (Bogie), shows up at the downtown office of the young doctor to say thank you and here’s 500 smackers for your trouble. He also starts dispensing advice. Spotting Doc’s racing sheet, he says betting on the horses is a sucker’s game. Then he looks around.

“Underworld” packs a lot into its 67 minutes. An elder doctor counsels a younger doctor, Niles Nelson (John Eldredge), not to perform a risky operation, since, if you don’t do it, it’s not your fault. (Dude puts the hypocrite into Hippocratic Oath.) He’s ignored and the surgery works. Turns out the patient is a gangster, and the gang leader, Joe Gurney (Bogie), shows up at the downtown office of the young doctor to say thank you and here’s 500 smackers for your trouble. He also starts dispensing advice. Spotting Doc’s racing sheet, he says betting on the horses is a sucker’s game. Then he looks around.

“I don’t get it. A guy with a pair of million dollar hands in a dump like this. Yeah, you’re wasting your time down here. You oughta be uptown with the big dough.”

Based on the first minute, we assume the doctor will toss Bogie out on his ear. Nope. When Doc’s wife, Dr. Carole Nelson (Francis), shows up, he repeats everything Gurney said as if they were his ideas. Next thing you know, they’ve got a fancy pad uptown, but now the Doc is hooked on horses and booze. Plus he’s a lazy bastard. When Gurney calls with another favor, he’s ready to bow out until Gurney gets an edge in his voice. So he goes, in the middle of the night, to pull another slug out of another body. Except now the cops are watching, and they come in blasting. Goodbye, Doc. Don’t have to worry about his story no more.

So it becomes her story. It become melodrama.

It’s odd what slips through the Hays/Breen Office in these Production Code movies. The cops in particular come off badly here. Not only do they kill the Doc while letting all the other gangsters get away, they then give the third degree to Carole. She keeps saying “Ask my husband” until they finally let her know, sorry, we already killed him. Oh, we’re also going to charge you with crimes based on no evidence. The public wants a show, the DA says, “and they’re going to get it.”

The press isn’t much better.

It’s as if she’s not a doctor herself.

She’s acquitted, of course, but her name is besmirched; so when she hears Gurney’s gang has been seen near the town of Wayne Center, NY, she decides to set up shop there. I guess she hopes to run into him and clear her name? Anyway, with Aunt Josephine (Jessie Busley), who veers between comic-relief fearful and brassy, she takes on some of the small minds of the small town—such as the established, elderly doctor who doesn’t like the competition—but mostly she fits in. The local grocery guy has her back, for example.

As for Gurney? He and his men are driving along when their tire blows out. Or was it shot out? And who’s that guy in the woods, standing and smiling benevolently? Obviously a tire blower-outer! No, he’s just that staple of 1930s cinema: the literary British love interest (cf., Leslie Howard). This time it’s Bill Stevens (James Stephenson), a smart, affable and self-effacing author. Also down-on-his-luck. Wait, isn’t that like exactly Leslie Howard in “Petrified Forest”? I’m sure some Warner Bros. exec said “Hey, get Bogie another Leslie Howard. That worked before.”

Stevens happens to be a Napoleon scholar, and that just happens to be the historical figure Gurney is fixated on, so he becomes pals with him. Then he asks Stevens to write his autobiography. Stevens tries to tell him the difference between bio and autobio and we get this nice exchange:

Stevens: What you want is a ghost writer.

Gurney: Nah, no mystery stuff. Just plain facts.

In the end, Carole saves the day with her smarts. Gurney has an infected eye so she gives him, and his men (and Stevens), eyedrops that temporarily blind them—just as the feds show up. Most of the men give up, but not Gurney. Blinded, he stalks Carole and Stevens throughout the house, with Carole protecting the blind Brit. Gurney gets his from the local sheriff. Then more good lines:

Gurney (dying): I guess … you’ll have to finish my book without me.

Stevens: The finish was written long ago.

I like that he says it sympathetically.

The best of Seilers

Is this my first Kay Francis movie? She’s fine, just … pristine. Under glass. Did she really work at Warners?

One of the comic-relief dudes in the gang—who isn’t that funny—is Charley Foy. He wound up narrating “The Seven Little Foys,” with Bob Hope playing his father, in 1955. Though he lived another 30 years, it’s his last credit.

The director is Lewis Seiler, who directed quite a few movies in his day (1920s-1950s) and not many winners. On IMDb, if you sort his feature films by rating, the first is a 1928 film he co-directed with Howard Hawks, and the second is a 1929 film called “Girls Gone Wild,” which probably got elevated by the recent adult entertainment franchise. The most famous Seiler-directed film is probably “Guadalcanal Diary.” He took very little interest in this film, according to IMDb. “According to various cast members, he would show up to set and start blocking scenes without having read the part of the script that was to be shot on that day.” It shows.

Meanwhile, the screenplay was adapted from a story by W.R. Burnett, who helped begin the gangster cycle with his novel “Little Caesar” in 1929, and then helped remake it with his novel “High Sierra” in 1941. He and John Huston helped adapt the latter one for the movies, and the star of this one became the star of that one. It changed Bogart's image, his career, his life.

Friday June 03, 2022

Movie Review: Kongo (1932)

WARNING: SPOILERS

1932 was a helluva year for jungle horror movies in which a crazed martinet terrorizes secondary cast members, two of whom fall in love, and who wind up escaping even as the martinet is killed by the local population he once controlled with an iron fist. At least that pretty much describes “The Island of Lost Souls” and this. “Lost Souls” is better.

Both have literary pedigrees—sort of. “Souls” is based on an H.G. Wells novel, while “Kongo” came from a 1926 Broadway play, written by an actor (Chester De Vonde) and a producer (Kilbourn Gordon), which starred Walter Huston as “Deadlegs” Flint, the martinet. Two years later it was made into the silent film “West of Zanzibar,” starring Lon Chaney. Four years after that, this, with Huston again.

Since then, nobody's touched it. For a reason. You know about revenge being a dish best served cold? This is a tale of revenge served old. And odd.

Sins of the father

Flint is a scarred man in a wheelchair in the middle of the African jungle who nevertheless controls huge swaths of territory because he’s convinced the local, dominant tribe, via magic tricks, that he’s some kind of god. He’s got two white servants, Hogan (Mitchell Lewis), tall and potentially menacing, and Cookie (Forrester Harvey), a squat comic-relief Cockney, as well as a Portuguese hottie, Tula (Lupe Velez), wearing a sarong, sweat and not much else. He controls them because he controls the booze supply, the fortune in ivory they have stashed, and the tribe. “The cripple can stop anyone from getting in or out of the juju circle,” Tula says. “I know, I’ve tried.”

He’s also got a sign tacked to a wooden post, “HE SNEERED,” below which he marks off time. Biding it, you could say.

Eighteen years earlier, a man named Gregg (C. Henry Gordon) had an affair with and impregnated Flint’s wife, then beat him up and crushed his spine. While he was doing the crushing, he sneered at him. Thus the sign on the wooden post. Flint has been planning his revenge ever since.

He should’ve planned it better. The revenge will fall mostly upon the child from the affair, Ann Whitehall (Virginia Bruce of “Winner Take All”), who, all but orphaned, has been raised in a convent in Cape Town. Flint sends Hogan to retrieve her, and the next thing we see, she’s crazed, crawling and booze-addicted like everyone else. Then we get another arrival: a Brit doctor named Kingsland (Conrad Nagel, playing Brit), who was once a gentleman (“FRCS,” he says). He came to the jungle to help those who were byang root-addicted but got addicted himself. Flint keeps him around because he wants him to operate on his back. He has no hope of walking, he just wants Kingsland to relieve the pain.

Of course, Kingsland falls for Ann, and helps relieve her jungle fever. Then Tula gets Kingsland addicted on the byang root again. (Don’t get her motivation here.) Then Flint uses the leeches in the swamp to cleanse Kingsland of his addiction so he can operate on his back. Along the way, Ann falls for Kingsland, too.

It’s all pretty stupid. No one acts against Flint when they should, and everyone tells Flint what they shouldn’t. And all of it leads, finally, please finally, to the showdown with Gregg.

Oddly, Gregg barely remembers him. (Just how many men has he cuckolded and crippled?) Then Flint reveals Ann, who’s crazed and drug-addicted again. He tells him it’s his daughter. He tells her tale with relish:

Forced through the squalor of a night house in Zanzibar, dragged here through the swamps, fed germ-laden water seeped in brandy, and here she stands before you—fever-ridden, broken, hopeless, degraded! I did that, Gregg! Do you hear?

Hearing all this, Gregg collapses. A few moments later, he rises, laughing. Because it’s not his daughter. The timeline is wrong. It’s Flint’s daughter. He did this to his own flesh and blood.

Which … of course. I mean, even if Ann had been Gregg’s daughter, it was a lousy plan—punishing the child for the sins of the father. And why suppose Gregg would immediately love the grown-up offspring he’d never met and didn’t know he had? And that her degradation would cause him immense pain? Part II was also nonsensical. He planned to kill Gregg, and, per native custom, his offspring, Ann, would then be burned alive. The majority of pain and suffering is again on Ann.

Instead, it’s Flint who immediately cares for Ann, who feels pain for all the suffering he’s caused her. But by now Gregg has been killed trying to escape and the natives are gathering for Ann. So Flint tells Kingsland about the tunnel to safety—that old bit. Then he holds off the natives with some hocus pocus and unga-bunga talk, stands, collapses, is killed. Everyone else gets away.

I like how, on the train home, Kingsland talks of marriage while Ann eyes him with something like doubt in her eyes. She almost looks trapped. Not sure if Virginia Bruce is a worse actor for this, or better. No word on whatever happens to Tula.

Anyway, I get why they don’t remake it anymore. Won't even get into the racial politics of it all.

And by god he knew voodoo

An MGM film, “Kongo” was directed by William J. Cowen, assistant director on the silent classic “The King of Kings,” whose own career didn’t go much further. “Kongo” was his third feature and he only directed two more. And then? Did he go into theater? Radio? He was married to Lenore Coffee, a successful writer, but most of his bio is about his WWI heroics.

I found more on the aforementioned playwrights. As an actor, Chester De Vonde was kind of a big deal in the late 1890s and early 1900s, had his own stock company, etc., but at some point he supposedly went into the jungle, came out with knowledge of voodoo, and then wrote this play with Kilbourn Gordon. Because of that, I assumed Gordon was a writer. He wasn’t. He was a producer. His biggest hit was “The Cat and the Canary,” which helped jumpstart the whole “reading of the will in a creepy mansion and people start dying” trope. He was also responsible for a string of 1920s plays that feel like they influenced comic book writers a decade later: “The Bat,” “The Spider,” “The Green Beetle.”

In a 1927 Wilmington, Del., Evening Journal profile, Kilbourn expounds on his artistic philosophy. It wasn’t very artistic:

“Somehow for a period, playwrights seemed to think that so-called artistic drama was the essential meat for the public and they wrote that sort of play. Just when that era was at its height I came upon ‘The Cat and the Canary’ and it proved by its success that they were all wrong. Then I encountered Chester De Vonde, actor and playwright these many years. Mr. De Vonde, with my collaboration, wove out of his experiences in Africa the play called ‘Kongo.’ And that scored.”

Though De Vonde died a year later, age 55, Gordon lived for another 50 years, until 1975; but for his final four decades there’s almost no mention of him in the newspapers—just society-page stuff about his children and grandchildren getting married. I can’t even find an obit. For decades he watched his legacy fade. One wonders how the “so-called artistic dramas” he disparaged fared during this time.

“The cuckolding and crippling I don't mind. But sneering is beyond the pale.”

Monday May 23, 2022

Movie Review: You Can't Get Away With Murder (1939)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Billy Halop of the Dead End Kids is third-billed here, but he’s really the lead. The movie’s on his shoulders. Too much.

He plays Johnnie, a Hell's Kitchen punk who begins palling around with hoodlum Frank Wilson (Humphrey Bogart) despite the positive example of his older sister Madge (Gale Page) and her fiancé, policeman Fred Burke (Harvey Stephens). It doesn’t help that sis and Burke are bland as all get-out.

A Shawshank vibe

Early on, Johnnie steals Burke’s gun, which Frank then uses in a pawn shop robbery that goes bad: Frank kills the owner. “Yeah, with Fred’s gun,” Frank tells a distraught Johnnie. “And you give it to me. You took it from the copper’s room. … There’s a murder rap hanging over both of us.” Shortly afterward, Johnnie and Frank are picked up by the cops—but for an earlier robbery. It's Burke who's arrested for the pawn-shop murder.

Early on, Johnnie steals Burke’s gun, which Frank then uses in a pawn shop robbery that goes bad: Frank kills the owner. “Yeah, with Fred’s gun,” Frank tells a distraught Johnnie. “And you give it to me. You took it from the copper’s room. … There’s a murder rap hanging over both of us.” Shortly afterward, Johnnie and Frank are picked up by the cops—but for an earlier robbery. It's Burke who's arrested for the pawn-shop murder.

At this point we’re 17 minutes into a 78-minute movie, and the rest of it boils down to this question: When will Johnnie come clean? He’s certainly worried about Burke but Frank says Burke’ll be fine. “He’s got an alibi, don’t he?” Then Burke is convicted and sentenced to death. Again Johnnie is worried, again Frank says what he says. Each iteration we get the same back-and-forth, and the emotional weight of it is always the same. Johnnie seems as worried at the idea Burke will be arrested as he is with the reality that in three hours Burke will be executed for a crime Frank committed. Plus we must get some variation of this conversation a half dozen times:

Concerned adult: You know something, Johnnie, something that will save Burke, and it’s weighing down on you. What is it?

Johnnie: I don’t know nuttin I tells ya!

Halop was good as the leader of the Dead End Kids, but you get why he never became a leading man. Put him in a suit and fedora next to Bogart and he’s just a kid playing dress up. Director Lewis Seiler doesn’t seem to help him much, either.

Anyway, that’s what’s wrong with the film: We keep spinning our wheels. Here’s what’s interesting about it. You can’t help but wonder if a young Stephen King saw it on late-night TV.

Most of the movie is a prison movie, most of the prisoners are colorful characters, and there's a real “Shawshank Redemption” vibe. Toad (George E. Stone) is the bookie who takes bets on whether guys fry or not; Sam (Eddie “Rochester” Anderson) is the hungry guy who reads recipes aloud to sate himself. There’s even a happy-go-lucky con named Red (Joe Sawyer), who is sure he’s going to get paroled. But the real “Shawshank” vibe comes from Pop (Henry Travers, Clarence the Angel in “It’s a Wonderful Life”), who runs the prison library and who trains Johnnie on the system. He’s quiet, kindly, moves slow. I immediately flashed on James Whitmore’s Brooks Hatlen. I'm not the first.

Get busy dying

So after spinning our wheels for 68 minutes, everything comes to a head on the same night Burke is to be executed for Frank’s crime:

- Frank and Scappa (Harold Huber) plot a prison escape

- Red is denied parole and joins the prison break

- Pop becomes ill

- Johnnie writes out his confession and leaves it for Pop

- Frank takes the confession

Only Red successfully makes it over the wall. Scappa screws the pooch, is killed. Holed up, Frank confronts Johnnie with his written confession, shoots him, and gives himself up. But Johnnie lives long enough to right the record.

Oddly, his first words aren’t about the pawnshop murder; they’re about himself. “Wilson … shot me,” he says. He says it twice, near death. Only then does he finally get around to saying what he should've said an hour earlier: Burke is innocent. Cut to the infirmary, surrounded by everyone, and Johnnie apologizing to Burke. He also tries to thank Pop, the movie’s true father figure, but Pop tells him to get some sleep. “You’re right, Pop,” he says, “I can …. sleep … now,” and his head drops off. He's dead, but at least his burden is over. THE END.

One question the movie doesn’t answer: Did Red get away? I like to think that he did. I like to think he made it across the border. I hope the Pacific was as blue as it had been in his dreams.

Friday May 20, 2022

Movie Review: San Quentin (1937)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Warner Bros. tosses a lot of its 1930s tropes into this thing but they don’t connect. At all.

The new tough-but-fair “Captain of the Guard” at San Quentin prison, Stephen Jameson (Pat O’Brien), becomes involved with a nightclub singer (Ann Sheridan) who is sister to one of the inmates (Humphrey Bogart). From that, for most of the movie, we're wondering two things. Can he reform the men? And can he do it without showing favoritism to the brother?

To which the movie gives us these answers: He kind of reforms the men. And he thinks he doesn’t show favoritism.

Forever blowing bubbles

At the start, San Quentin is a mess, run by Lt. Druggin (Barton MacLane), a martinet whose answer for any infraction is taking away privileges and a month in the hole. But his draconian ways create more problems than they solve—the men keep rebelling—so the warden, and the prison board, bring in an actual army captain.

Mouse over for 1940s rerelease.

Odd coincidence: The night before Jameson begins, he meets and falls for lounge singer Mae de Villiers, nee May Kennedy (Sheridan). Odder coincidence: That very night, her brother, Joe “Red” Kennedy (Bogart), shows up backstage and asks for some dough. He says he needs to get to a new job in Seattle but he’s actually on the run from the cops, and they catch up with him in Mae’s dressing, in front of both Mae and Jameson, and haul him away—to San Quentin, of course.