Movie Reviews - 1940s posts

Friday June 17, 2016

Movie Review: The Red Menace (1949)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“The Red Menace,” a 1949 B-picture from Republic Studios, was one of the first anti-communist movies to be released during the post-WWII Red Scare, but from a distance it’s kinda quaint. Sure, there’s a Soviet cell operating in the U.S., but it’s the furthest thing from effective. A better title for the movie might be: “Red ... Menace?”

A tall, broad-shouldered lunkhead, Bill Jones (Robert Rockwell), is pissed that he’s been ripped off in some GI real estate scam and the government won’t do anything about it. Overhearing, a party member invites him to a nearby bar “for discriminating people,” where two broads make a play for him. While the brunette, Yvonne (Betty Lou Gerson), looks on disgruntled, the blonde, Mollie O’Flaherty (Barbra Fuller), takes him back to her place and mixes drinks while he peruses the shelves and ... Hey, what are these books? Marx? Lenin? You’re a commie! Yeah, but a looker. C’mere. Pucker up, baby.

Irish Italian Jewish Negro

The Soviet cell that Bill Jones is slowly indoctrinated into is like one of those WWII movie platoons: someone from every race:

- Henry (Shepard Menken), a nice Jewish poet, cuckolded by Mollie on a weekly basis.

- Mollie, Irish Catholic, whose mother hangs around like a gray cloud, mourning the loss of her daughter’s respectability.

- Sam, the affable Negro front-office worker at The Toilers, the commie newspaper.

- Reachi, the Italian, who wonders if communism is a democracy as they say, why is it called “a dictatorship of the proletariat”?

- Nina, the foreign beauty, who will become The Love Interest.

Things first go south when Reachi is killed in a back alleyway for asking questions. Then Henry gets curious, too, and is kicked out of the party. He quickly turns into a patriot:

At least that [American] flag has three colors in it, not one. Not one bloody one!

But he can’t take the ostracism and throws himself out a window. He leaves a note for Mollie, telling her to return to her mother, which she does; in a church. Sam leaves with his respectable father, while Yvonne, always ratting out others, is picked up by the cops, who, it turns out, know everything. (Because our law enforcement is on the case.) Then she goes mad. (Because that’s what happens to commies.)

That’s it. The filmmakers, I’m sure, wanted to make sure communism didn’t seem attractive, but they were so successful they made it seem hardly a threat at all. Which makes the way the movie is bookended even odder.

‘We can’t suspect everybody’

It opens steeped in paranoia. Nina and Bill flee California, sure that communists are right behind. At an Arizona gas station, the attendant makes small talk—Where are you from? Where are you going?—and Nina freezes:

Nina (whispering): Why’d he say that?

Bill: Just to make conversation probably.

Nina: I don’t believe it. There must be some reason why he’s so curious.

Bill: Take it easy, Nina. We can’t suspect everybody.

After we get the rest of the story in flashback, we see them driving into Talbot, Texas, where Bill suddenly becomes sensible: “I’ve been thinking, Nina. What are we running away from? This is the United States not a police state. Let’s go see that sheriff.” Which they do. And they tell him their tale. (This really should’ve been the spot for the flashback, but the movie screwed up that, too.)

The sheriff’s response to their tale?

You folks have been running away from yourselves, and the fear in your own minds.

The entire movie is an argument against the paranoia of groups like HUAC, presented as an argument in favor of such groups.

Nobody on either side of the political fence saw this. The Daily Worker denounced the movie, while California’s own HUAC, the Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities, honored it, commending “Republic Studios and those persons who have so courageously assisted in this production.”

And then, like most anti-communist movies, it died at the box office. No one went to see it because that stuff's a drag: preachy, heavy-handed. It's called the free market.

Monday March 14, 2016

Movie Review: Intruder in the Dust (1949)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Intruder in the Dust” was one of several movies produced in the short progressive period between the horror of the Holocaust (when tolerance suddenly seemed like a good idea) and the paranoia of the Red Menace (when fuck it). They were called “message movies” or “problem pictures” and included such films as “Gentleman’s Agreement” and “Crossfire” (anti-Semitism), “Pinky” and “Home of the Brave” (racism).

“Intruder,” also about racism, only got made because of one man, Clarence Brown, who learned at the feet of Maurice Tourneur, Jacques’ daddy, during the silent era, then became one of the main dudes at MGM during its lush glory days. He was also a member of the right-wing Motion Picture Alliance, and a Southerner, making him an odd choice to push for such a racially progressive picture.

Why did he do it? In Patrick McGilligan’s book, “Film Crazy: Interviews with Hollywood Legends,“ he talks about being in Atlanta during the 1906 race riots when 16 black men were lynched. Three decades later, William Faulkner published his novel about a near lynching, and as Brown recounts:

Why did he do it? In Patrick McGilligan’s book, “Film Crazy: Interviews with Hollywood Legends,“ he talks about being in Atlanta during the 1906 race riots when 16 black men were lynched. Three decades later, William Faulkner published his novel about a near lynching, and as Brown recounts:

I didn’t walk, I ran up to the front office at MGM. “I’ve got to make this picture,” I said. “You’re nuts,” said [Louis B.] Mayer, because the hero was a black man. “If you owe me anything, you owe me a chance to make this picture,” I said.

There were battles throughout production—both on location in Oxford, Mississippi (Faulkner’s hometown), and at MGM. Mayer felt the protagonist, Lucas Beauchamp (Juano Hernandez), was “uppity,” and that the picture would lose money. He was right about the latter—did it even play in the South?—but the picture earned critical raves. The National Board of Review included it on its top 10 list, and it finished second to “All the King’s Men” in the New York Film Critics Circle’s best picture category. It received multiple nominations from the WGA, Golden Globes, and British Academy, and won BAFTA’s short-lived “UN Award” (for the film “embodying one or more of the principles of the United Nations Charter”). In The New York Times, Bosley Crowther wrote, “By all our standards of pre-eminence, this is—or will prove—a great film.”

He’s right. At the least, I was startled by how good “Intruder” is. The cinematography is often reminiscent of Dorthea Lange’s Dust Bowl photographs, while Beauchamp (pronounced “Beach-em”) is a type of rich, powerful African-American character that Hollywood, always worried about the Southern market, rarely allowed to be seen on screen.

It also bears a passing resemblance to a later, much-beloved film. Maybe more than a passing resemblance.

Before Atticus, before Superman

Seriously, when “To Kill a Mockingbird” was published in 1960, didn't anyone bring up “Intruder in the Dust”? Let's count it off:

- A black man is jailed for a horrific crime.

- He’s represented by a white lawyer.

- A kid, related to the lawyer, is central to the story—the main character, more or less.

- There’s a standoff on the courthouse steps between an unarmed white person and a white mob, who want to lynch the black man.

- The real criminal is a white relative of the victim.

Yes, there are differences. It’s murder rather than rape. The black man here, Beauchamp, is proud, almost haughty, as opposed to the humble, bland Tom Robinson. Our lawyer, John Gavin Stevens (David Brian), is no Atticus, and starts the case assuming his own client guilty. Rather than the lawyer’s children, Scout and Jem, it’s the lawyer’s teenaged nephew, Chick (Claude Jarman, Jr.), who acts as our eyes and ears. Oh, and Stevens proves Beauchamp innocent even without a trial. Apparently, in 1949 Mississippi, the criminal justice system worked.

The courthouse-steps confrontation not only prefigures “To Kill a Mockingbird” but—indulge me—“Superman vs. The Mole Men,” an hour-long intro to the 1950s TV series, in which the Man of Steel stops a Texas mob from lynching an alien. Of course, being Superman, he’s hardly unarmed, but otherwise the dynamic is the same as in the other two: the stalwart one (without a gun) against the angry many (Southern racists) to protect the defenseless one (black/alien). (Note to readers: If you know of other such scenes in novels/movies, write me.)

Here, the stalwart one is old Southern white lady, Miss Eunice Habersham (Elizabeth Patterson), sitting in a rocking chair and doing her mending. Why her? Calculation on the part of Stevens. The mob, he says:

...would pass even [deputized] Will Legate sooner or later when there's enough of them. But there's one thing that would stop them. Long enough anyhow. And that's somebody without a gun. [Pause] A lady. [Pause] A white lady.

I have to admit, I always found the “Mockingbird” scenario absurd. Atticus thinks one unarmed man can turn back a mob in the middle of the night? Him and his lamp and his book? Really, he’s only saved because Scout and Jem show up, and Scout (a white lady) asks questions of different people in the mob. She humanizes them.

Faulkner’s way is smarter, and Patterson, supposedly handpicked by Faulkner, is a story in herself. Born in Tennessee in 1875, 10 years after the Civil War, she died in 1966, a year after the 1965 Voting Rights Act. She began her career on stage, and became a frequent character actress on Broadway before doing the same in movies. The subhed to her New York Times obituary reads: “Was Said to Have ‘Played Mother of About Every Star in Hollywood.’” Here, she mothers this role into being. She was Atticus before Atticus, Superman before Superman.

Her nemesis in the scene is the perfectly named Nub Gowrie (Charles Kemper), the brother of the deceased, and the man who actually did the killing. He’s a Southern stereotype—fat, ineffectual, unethical—but you also get a sense of a man trapped in his role. As in Orwell’s “Shooting an Elephant,” Nub is propelled along by the expectations of the mob.

There’s already a sleepy, carnival atmosphere in town, as folks gather to watch the lynching, and Gowrie, sitting in his truck, is confronted in by-the-way fashion. A woman with a baby begins it. (Think about that for a moment.) She says, “Well, Mr. Gowrie, when you reckon you gonna get started?” Jokes are made, Nub gets fed up, and after he gets a metal canister overflowing with gasoline, he walks across the street, sloshing things as he goes, to confront Miss Eunice through the screen door. She refuses to budge. So he dumps gas on the floor, and, with a bully’s grin, lights a match.

Miss Eunice: “Could you step out of the light so I can thread my needle?”

And that defuses it. Literally. Nub waves the fire out, puts the match in his shirt pocket (nice touch), and we get the following exchange:

Nub: Miss Habersham, I ain’t gonna touch you now. You’re an old lady but you’re in the wrong. You’re fightin’ the whole county but you gonna get tired. And when you do get tired, we gonna go in.

Miss Habersham: I’m goin’ for 80 and I’m not tired yet.

Then she stands up, goes to the porch, and talks to the crowd. “Go home! Everyone one of you, go on home. You oughta be ashamed!” Trying to shame the crowd. So she was Joseph Welch before Joseph Welch, too.

To be honest, I think the scene should’ve ended with “I’m not tired yet.” But the movie keeps doing this. It keeps pulling back to make grander, progressive points that deflate the power of its smaller scenes. It doesn’t trust its micro and insists upon the macro. It wants pontification.

The worst example is in the movie’s penultimate scene.

Micro > Macro

“Intruder” opens beautifully with the arrival of Beauchamp in the custody of the benevolent sheriff (Will Geer), and his walk through a gauntlet of tense, Southern faces. Beauchamp, unbowed even in handcuffs is almost contemptuous here; and on the courthouse steps, he turns and orders Chick to get his uncle to represent him. Interestingly, though he asks for him, he never confides in the uncle; he confides in Chick, with whom he has a history. Halfway through the movie, Stevens wonders over this. Why didn’t Beauchamp trust him? It’s Miss Habersham who answers: “You’re a white man,” she says. “Worse than that, you’re a grown white man.” Worse than that. From a 1949 movie? Amazing.

Most of the movie’s casting (Miss Eunice, Beauchamp) is perfect, but Brian, I have to say, is all wrong for Stevens. Born and bred in New York, he doesn’t attempt a Southern accent; he just has that bland, post-World War II voice. There’s something unpleasant about him in look and manner, too; something pinched in the eyes. In his obit, from 1993, the Times wrote, “Mr. Brian repeatedly portrayed characters who were ruthless or powerful or both, including some villains in Westerns,” and I can see it. But maybe that’s what makes him right for this? Stevens isn’t an Atticus, after all. He’s supposed to be the hero but he actually gets in the way of justice. Everyone else does the hard work—digging up graves, jumping into quicksand—while he stands around pontificating and sucking on his pipe.

He’s doing the same in the movie’s penultimate scene.

By this point, Nub has been arrested for the murder of his brother, the crowd dispersed, Beauchamp freed. We get some awful dialogue between Chick and Stevens as they watch the crowd disperse (“It’s alright, Chick”/“Is it?”), when silence would’ve spoken volumes. Then a few days later, Beauchamp shows up at Stevens’ office to settle his debts, but Stevens, all paternal benevolence, refuses payment since he didn’t do anything. (He’s right.) Beauchamp insists; Stevens mentions that he did break his pipe, and it cost two dollars to fix. Beauchamp says he’ll pay for that, then pays him with: a bill, two quarters and 50 pennies. “I was aimin’ to take ’em to the bank, but you can save me the trouble,” he says, with a glint in his eye. Then he insists, as in any transaction, that the pennies be counted. Stevens, still with the upper hand, tells him to do it. Which he does. And as he does, we get this exchange:

Stevens: That night in the jail—why didn’t you tell me the truth?

Beauchamp: Would you have believed me?

It seems straightforward enough, this back-and-forth, but there are chasms beneath it. Stevens is acting the great white father here, even though he knows what he knows; and instead of playing along, Beauchamp calls him on it. Beneath the bland words, he’s calling Stevens a racist. And that’s too much for Stevens, our ostensible hero, whose face suddenly darkens and becomes pinched; and he puts up a barrier—a book—between himself and Beauchamp. He expects Beauchamp to leave. But Beauchamp doesn’t leave. He keeps standing there until Stevens testily admonishes him.

Stevens: Now what. What are you waiting for now?

Beauchamp: (Standing taller) My receipt.

Holy crap, that’s good. The movie really should’ve ended there (the novel, in fact, does), or with Beauchamp walking outside, and through the town, and past the people that wanted to lynch him just a few days earlier. But instead we pan back to Stevens and Chick on the balcony, watching Beauchamp. And we get more pontificating:

Chick: They don’t see ‘em—as though it never happened. ... They don’t even know he’s there.

Stevens: But they do—same as I do. They always will as long as he lives. Proud, stubborn, insufferable. But there he goes, the keeper of my conscience.

Chick: Our conscience, Uncle John.

(Music wells up: THE END)

MGM saves the white man in the end by letting him sound profound; by pretending he’s the hero. The story knows different.

SLIDESHOW

Wednesday March 09, 2016

Movie Review: Mission to Moscow (1943)

WARNING: SPOILERS

If I’d been a member of HUAC back in 1947, this is the movie I would’ve focused on. Screw the others. Seriously, someone saying “Share and share alike” in a Ginger Rogers movie? Gregory Peck and Paul Muni portraying allied soldiers as heroes? Russian peasants smiling? You look small just bringing it up. You look like bullies. Which you were.

But “Mission to Moscow”? Good god, is there a movie more wrong in the history of Hollywood?

At the same time, I don’t think Hollywood is to blame for it.

Stalin: for all mankind

Some background: In 1941, Simon & Schuster published a book, “Mission to Moscow,” by Joseph E. Davies, about his experience as U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union from 1936 to 1938. Once the U.S. entered World War II, according to Jack Warner, Pres. Roosevelt urged him to make a movie out of it, which Warner Bros. studios did, with Walter Huston, Abe Lincoln himself, as Davies.  The real Davies not only introduces the movie (in ponderous fashion), he had creative control over the script. And when he didn’t like the original draft, Jack Warner tapped Howard Koch to do the rewrite. Four years later, as a friendly witness before HUAC, Jack Warner denounced Koch as a communist sympathizer for that work, and he was later blacklisted.

The real Davies not only introduces the movie (in ponderous fashion), he had creative control over the script. And when he didn’t like the original draft, Jack Warner tapped Howard Koch to do the rewrite. Four years later, as a friendly witness before HUAC, Jack Warner denounced Koch as a communist sympathizer for that work, and he was later blacklisted.

Politically, Koch was definitely on the left, stumping for Henry Wallace in 1948, for example, but that’s only a crime to the Breitbarts of the world. One of the original “Hollywood 19” called before HUAC, he was also the first to break ranks with their ultimately unsuccessful legal strategy. In an open letter in The Hollywood Reporter in November 1947, he went his own way. Meanwhile, scapegoated and fired by Warner, he freelanced for a few years (“Letter from an Unknown Woman” for Max Ophuls) before work mysteriously dried up; so in 1950 he moved to England, where he continued to write under a pseudonym. He eventually returned to the U.S. and settled in Woodstock, NY, wrote several forgettable screenplays in the 1960s, published his memoir, “As Time Goes By,” in 1979, hocked his Oscar to pay for his granddaughter’s law school in 1994, and died in 1995 at the age of 93. (Heather Heckman, a Ph.D. student at Madison, goes deep into Koch’s story here.)

That Oscar, by the way, was for writing “Casablanca.” He also wrote “Sergeant York.” That’s your communist sympathizer. Sergeant York. Only in America.

The director of “Mission,” meanwhile, was Michael Curtiz, whose previous films had been “Casablanca” and “Yankee Doodle Dandy,” and who went on to make “This is the Army,” starring Ronald Reagan, among others. Another obvious com-symp.

So how did we get this apology for Stalinism? The problem, I assume, is Davies. The dude was just wrong about everything.

In some respects, “Mission” is a typical, corny, Hollywood movie. As it opens, Davies, a lawyer, is about to go on a long-delayed lake vacation with his wife and daughter (Ann Harding and Eleanor Parker), when he’s pursued in a boat by his chauffeur Freddie (George Tobias, Abner Kravitz of “Bewitched”), with news of a phone call. “I don’t care if it’s the president of the United States!” Davies cries. Setting up the obvious punchline and titular mission. FDR wants him to suss out both Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in terms of the looming war.

When he arrives in Germany? Awful! Davies looks with disgust as Hitler Youth march near the Hamburg train station. When he arrives in Russia? Great! Davies looks with delight as Soviet troops train near the Moscow train station.

How good are things in the Soviet Union? Very good! Caviar is plentiful, gender discrimination nonexistent, workers happy. The Soviet leaders, meanwhile, are down-to-earth and open-minded. “I believe in individualism as it’s practiced in America,” Davies declares upon arriving. “All we want is that you see all that you can before you arrive at your conclusion,” Soviet leaders respond sagely.

He visits a factory and is amazed by its output. His wife visits a department store (run by Mrs. Molotov) and is amazed by its luxury items. He’s told that the harder the people work, the more money they make. “The greatest good for the greatest number of people,” he’s told. “Not a bad principle,” he responds. “We believe in it, too!”

Ah, but there’s trouble in paradise. Sabotage! Betrayal! And in whose name? Nazi Germany! Thus we get a truncated, laughably incorrect version of the show trials, the Stalinist purges, that led to the death of millions of innocent people. But here, no one’s innocent. Here, they all confess without pressure. “The only pressure came from my own conscience,” says one saboteur stoically. “Based on twenty years of trial practice,” Davies pontificates from the cheap seats, “I’d be inclined to believe these confessions.”

Seriously, you couldn’t create a better dolt if you’d tried. At one point, others in the U.S. embassy are suspicious of the Soviets. Not Davies:

U.S. official: The Kremlin may be recording every word we say.

Davies: Well, perhaps they have a reason. Moscow is a hotbed for foreign agents.

Official: But eavesdropping, sir! Why that is an open affront of international rights!

Davies: I never say anything outside the Kremlin about Russia that I wouldn’t say to Stalin’s face, do you?

Official: Well, that’s putting it rather stiffly sir.

Davies: Then stop gossiping and stop listening to it. We’re here in a sense as guests of the Soviet government. And I’m going to believe they trust the United States as a friend until they prove otherwise.

The kicker is when he meets Stalin himself, and tells him, “I believe, sir, history will record you as a great builder for the benefit of mankind.” Then it’s off to Britain for a meeting with an up-and-comer, Winston Churchill, to tell him how the world really works.

At home, as war approaches, Davies makes excuses for everything Stalin does. The Nazi-Soviet Pact? Stalin had to do that to give himself more time to prepare for war. Attacking Finland? Finland asked Russia to attack it—to protect herself against German aggression.

You can barely watch “Mission to Moscow” for the number of times you facepalm.

War-time propaganda

Occasionally, we get something good. I like the conversation Davies and his family have on a train bound for Berlin:

German: You Americans have a very good tobacco. Ours is terrible—at the moment. We tend to improve it. Very shortly.

Mrs. Davies: Really? What do you intend to buy?

German: I’m not so sure we’ll have to buy from anyone. Our Fuehrer is a very clever man. He has many ideas. ... We Germans don’t mind a few discomforts now because we know what’s in store for us in the great future life.

Davies’ daughter: You mean on earth or somewhere else?

German: Shall we say, somewhere else on Earth.

That’s nice wordplay, and the scene isn’t overdone. Throughout, Curtiz plays with shadows well, as he always did. He’s a pro, Koch is a pro, it’s a Golden Age Hollywood movie.

And it’s still atrocious.

Even so, I would argue “Mission to Moscow” is less communist propaganda than war-time propaganda. If it stands out, it’s because the rest of our war-time propaganda (portraying Japan and Nazi Germany as cruel regimes), was, if anything, underplayed against the awful reality. There’s no conspiracy here, just stupidity. “Mission” is a tale told by an idiot, but the idiot didn’t come from Hollywood.

Thursday March 27, 2014

Captain America (1944): The Slideshow Review

Tuesday March 25, 2014

Movie Review: Captain America (1944)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Captain America was born fighting the Nazis. Literally.

On the cover of Captain America #1, artist Jack Kirby, not yet “Jolly Jack,” and truthfully never really “Jolly Jack,” drew Cap infiltrating Nazi headquarters. On the wall there’s a “television” showing a man blowing up a U.S. Munitions Works. On a nearby table, we see a map of the U.S.A. along with “sabotage plans” for same. And front and center, there’s Cap, in all of his red-white-and-blue glory, and with bullets zinging off his then-badge-shaped shield, decking Adolf Hitler. It was March 1941. Pearl Harbor was nine months away. Captain America was fighting the Nazis almost a year before America was fighting the Nazis.

The Republic Pictures serial “Captain America” was filmed and released in the midst of World War II (1943 and Feb. 1944, respectively), so you’d think you’d see him decking a few Nazis, if not Hitler himself, but neither is seen in this thing. Captain America isn’t in Europe, he isn’t a soldier, he isn’t even Steve Rogers.  He’s Grant Gardner, district attorney (Dick Purcell), fighting the Scarab (Lionel Atwill), a typical movie serial villain. There’s no Bucky, no shield, and no origin, either. The movie begins with Captain America a known figure, but there’s nothing particularly super about him. He’s not stronger than 10 men. He sometimes loses fights with one. He relies on a gun. Basically he’s a dumpy, middle-aged D.A., who, in the midst of a bumbling investigation into multiple murders, takes off his suit to reveal a red-white-and-blue outfit, with which he goes forth to engage in prolonged fistfights with two (always two) henchmen in a barn or a factory or a garage or a cave. If we didn’t know the tropes of superhero movie serials, we would think him insane.

He’s Grant Gardner, district attorney (Dick Purcell), fighting the Scarab (Lionel Atwill), a typical movie serial villain. There’s no Bucky, no shield, and no origin, either. The movie begins with Captain America a known figure, but there’s nothing particularly super about him. He’s not stronger than 10 men. He sometimes loses fights with one. He relies on a gun. Basically he’s a dumpy, middle-aged D.A., who, in the midst of a bumbling investigation into multiple murders, takes off his suit to reveal a red-white-and-blue outfit, with which he goes forth to engage in prolonged fistfights with two (always two) henchmen in a barn or a factory or a garage or a cave. If we didn’t know the tropes of superhero movie serials, we would think him insane.

Of fistfights and vibrators

Why watch the 1944 movie serial “Captain America”? For the history of it, I suppose. We get to see how far we’ve come. We get to see what fascinated kids—or what movie executives think fascinated kids—70 years ago.

So what fascinated kids 70 years ago?

A masked superhero? Check. Although feel free to put quote marks around “super.”

Mystical, exotic locations? Check. A group of scientists have recently returned from excavating an ancient Mayan ruins, from which they’ve discovered the usual: plant extracts that allow you to hypnotize people and make them do whatever you want, etc. Plus a lost city.

The magic gizmos of science? Check. Has anyone tabulated these, by the way? The inventions that scientists created in movie serials of the ’30s and ’40s? I think it would be worth a study. (Someone else’s study.) In this 15-chapter serial alone we get the following:

- A thermodynamic vibration engine: it can destroy buildings.

- A portable electronic firebolt: it cuts through safes.

- A robot-controlled truck.

- A radio dictograph: a bug, basically.

- A perpetual life machine: it can bring people back from the dead.

I’ll talk more about the last one, introduced in chapter 11, later. It’s the first one, though, introduced in the first chapter, that had me snickering like Beavis and/or Butthead. Because it led to lines like this:

- “I want to know more about the vibrator!”

- “We’re not the only ones who know the secret of Lyman’s dynamic vibrator!”

- “Mr. Merritt and Mr. Norton are here to witness your demonstration of the vibrator! ... I know the secret of this machine and it’s a heavy responsibility.”

Indeed.

The Scarab is really Dr. Cyrus Maldor, who was a participant in the recent scientific expedition to the ancient Mayan ruins. Now, behind the bland facade of the Drummond Museum of Arts and Sciences, with its suspicious-looking shoeshine boy out front, he’s killing off all the other members of the expedition. Why? We don’t find out until Chapter 13. It has to do with two halves of a map to the fabled Lost City of Zada, where riches beyond anyone’s imagination can be found.

So ... money. Always money.

The problem with the radio dictograph

Look, I know the deal. I know these serials were made quickly, with little budget, a long time ago, and designed to keep viewers coming back next week. I guess I just want them to sense within their own framework.

Maldor? The Scarab? He can hypnotize people. So if the end game is the other part of the map, why not hypnotize people into revealing who has it? Why not hypnotize them into finding out where it is. They can do your work for you. Instead, he has them commit suicide. Then he goes after Prof. Lyman’s vibrator. Why? I’m not sure. The next chapter it’s the firebolt. So he can crack safes. What does that have to do with the Lost City of Zada? And why doesn’t he just hypnotize guards or bank managers to get into the safes? Seriously, the man needs to focus. But focus has never been big in movie serials.

My favorite nonsense bit is from Chapter 14 when the Scarab finally captures G.F. Hillman (John Hamilton, Perry White from the “Adventures of Superman” TV series), the man who has the other half of the map. Hillman is taken to a secluded farm, where Maldor reveals himself to be the Scarab. Then he says the movie-villain line: “You are very headstrong. But there are ways of making you talk.”

Ah, back to the hypnosis, I suppose.

Nope. “Tie him to that chandelier!” he says. Then he whips him.

Did he forget he could hypnotize people into telling the truth? Is he a sadist? Did he just need the exercise?

Neither of our principals is exactly Einstein. By Chapter Six, Maldor suspects Gardner is Captain America. That’s why they bug his place. But when Gardner returns home, his assistant, Gail Richards (Lorna Gray), reaches him on the phone and mentions in passing that his line has been busy. This clues Gardner in. Someone has been in his apartment! And he finds the radio dictograph. Now he has the upper hand! He knows, but they don’t know he knows. So what does he do?

At this point, the Scarab is blackmailing an oilman, J.C. Henley (Tom Chatterton), for a million dollars. So Gardner tells Henley, within range of the bug, that they’re including a “radioactive cell” in the briefcase full of money. “By means of triangulation,” he says, “we can locate the case wherever it is taken.” But it’s a lie. They’re not bugging it at all. The oilman is confused. So are we. How does this help? They’re letting the bad guys know they can locate them when they really can’t. Gotcha! Or ... would .... if we knew where you were. Really, the whole thing is just an excuse to leave the briefcase in the hills atop Los Angeles, so there can be a fight in a nearby cave, during which Captain America will fall down a mineshaft and ...

And we start over again.

The radio dictograph? Forgotten in the next episode. The briefcase full of money? Taken. But Gardner does plant a story in the press about how the bills were all marked, so they’re useless to the Scarab. Ha ha. Except all this does is refocus the Scarab’s anger on Henley. “I was a fool to take your advice” Henley says to our hero. Totally. Plus you’re out a million bucks. That money ain’t coming back.

At least Henley lives. More than you can say for others under Gardner’s protection. Prof. Lyman (Frank Reicher), he of the dynamic vibrator, dies in Chapter 1. The inventor of the electronic firebolt, Prof. Dodge (Hugh Sothern), lasts a few chapters before getting it in Chapter 5. Then Lyman’s brother, Dr. Clinton Lyman (Robert Frazer), comes onto the scene with the greatest invention of all: He can reanimate the dead! Wow. This may be the greatest invention of all time. And what does he get for his trouble? Dead. Somehow this ineptitude is spun into heroic deeds for Gardner and Captain America. At one point, the Scarab, still intent on revenge on Henley, sends two men to blow up his Gas Works plant. Captain America battles them but can’t turn off the pressure gauges. Kablooey! The report on the radio the next morning? Only one of the buildings blew up “... thanks to the timely arrival of Captain America!” Some press agent he’s got.

The greatest insult may be how often Captain America gets a bead on the two henchmen in the remote location but for nothing. It works this way. They’re planning something nefarious. He shows up with gun drawn. One of them throws something at him and knocks the gun loose. Then there’s a fistfight. Then he is imperiled and ...

See you next week.

The final death

Interestingly, for all its faults, the serial has been praised by fans of the genre. They say it’s Lionel Atwill’s best work—and he’s not bad in it. They say the fight scenes are among the best—and they’re athletic and well-choreographed. But it’s still a dance whose outcome we know. It’s still painful to watch.

This doesn’t help: Did the strain of making the serial contribute to actor Dick Purcell’s death by heart attack at the age of 36, just a few months after filming? He’s often called the first actor to play Captain America; but he’s also the first actor who died suddenly after playing a superhero. We call it the Superman curse but maybe it should be the superhero curse.

Captain America was only the fourth comic-book-based, live-action superhero to show up on our movie screens—after Captain Marvel (1941), Batman (1943), and The Phantom (1943)—but he wouldn’t return for another 35 years, and even then it was on the small screen in an abysmal 1979 TV movie starring Reb Brown. Eleven years later they tried again, with Matt Salinger, and with worse results. (Jack Kirby fought to get his name on the movie; after its premiere, he wanted to get his name off the movie.) Meanwhile, Superman and Batman movies are being made again and again. Then X-Men movies and Spider-Man movies and the Fantastic Four and even freakin’ Ghost Rider starring Nic Cage. But Cap? Bupkis.

It wasn’t until 2011, 67 years after this one, that Cap finally became the subject of a theatrical movie that got released in the U.S., “Captain America: The First Avenger,” starring Chris Evans. They got it right, too. They had him fighting Nazis.

SLIDESHOW

Tuesday June 04, 2013

Movie Review: Superman (1948)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The 1948 movie serial, “Superman,” the first live-action cinematic recreation of the Man of Steel, becomes, in the latter stages of its 15 chapters, a battle between two groups intent on avoiding the cops. The first group is led by the villainous Spider Lady (Carol Forman), queen of the underworld, who circumnavigates the law for obvious reasons. The second group is led by Perry White (Pierre Watkin), editor of The Daily Planet, who, along with his reporters, Lois Lane (Noel Neill), Jimmy Olsen (Tommy Bond) and Clark Kent (Kirk Alyn), just wants a scoop.

In Chapter 11, for example, “Superman’s Dilemma,” the Spider Lady needs “mono chromite” to complete her work on “the reducer ray,” so she sends several tough guys over to Frederick Larkin, chemical engineer. Larkin tells them it’ll take awhile to get the stuff ready. Then he goes to his card files and reads the following under “mono chromite”:

DEVELOPED BY DR. ARNOLD GRAHAM

RESTRICTED MATERIAL

IF ASKED FOR WITHOUT CREDENTIALS,

NOTIFY PROPER AUTHORITIES

So he calls the cops. Actually, no. He calls Perry White. And he calls the cops. Actually, no. He sends Clark Kent over to get the story.  Except Lois tricks Clark into being arrested so she can get the scoop. But that doesn’t happen, either. Instead, Lois nearly suffocates in a safe, Jimmy Olsen is nearly shot to death in a crate, and, in the end, Perry White, the man who never called the cops, chastises them all for not getting the scoop. Meanwhile, the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

Except Lois tricks Clark into being arrested so she can get the scoop. But that doesn’t happen, either. Instead, Lois nearly suffocates in a safe, Jimmy Olsen is nearly shot to death in a crate, and, in the end, Perry White, the man who never called the cops, chastises them all for not getting the scoop. Meanwhile, the fate of the world hangs in the balance.

Do the police get any respect here? In Chapter 13, Superman captures one of the Spider Lady’s goons, Anton (Jack Ingram), and flies him to the police station. Actually, no. He flies him to The Daily Planet and delivers him to Perry White. In Chapter 14, the Spider Lady sends her minion, Dr. Hackett, into the Metropolis streets to be arrested so he can communicate with Anton in prison. Who captures him? Lois. Who convinces the cops to put Hackett in Anton’s cell? Lois. It isn’t until the final chapter, “The Payoff,” that the Spider Lady finally, finally, contacts the police via shortwave radio. What does she say? “I want you to send a message to Perry White.”

They do her bidding. Apparently they know who the proper authorities are, too.

Early CGI

I know, I know. A cheap shot for a cheap, 65-year-old Columbia serial.

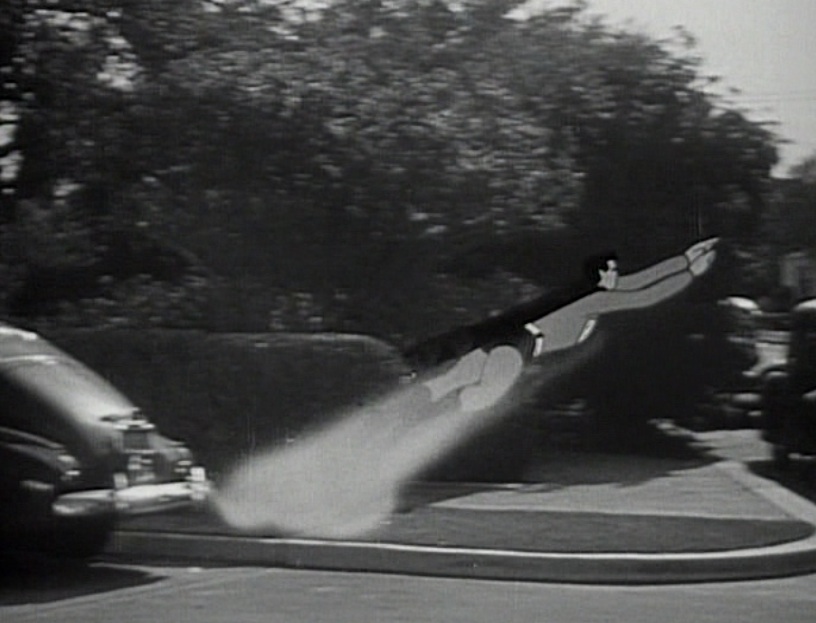

Except “Superman” wasn’t cheap. According to Glen Weldon in his book, “Superman: The Unauthorized Biography,” it was the most expensive serial ever made, with a budget of $350,000. It just looks cheap, even for the time. Six years earlier, in the 12-chapter serial “Adventures of Captain Marvel,” Republic Pictures did a pretty good job of making Tom Tyler, the star, appear to be flying (with a mannequin, a stuntman, etc.), but Columbia couldn’t be bothered. So they rely on animation. Superman takes a step, a feint into the air, and turns into a cartoon. Think of it as early CGI.

The first chapter, “Superman Comes to Earth,” is probably the most interesting. For the first time we get to see Krypton, which, in outdoor shots, looks like the parts of southern California where they shot the Gorn episode of “Star Trek,” and whose cityscape could be a 1920s “Amazing Stories” magazine cover. As always, the Kryptonian Science Council is full of assholes, who, in their resistance to scientific reasoning, resemble nothing so much as the modern GOP; but Jor-El (Nelson Leigh), a caped scientist, hardly helps his cause when he’s asked to provide facts. “We must be guided by my knowledge,” he responds, finger in the air, “which this august body has always respected.” Dude, a pie chart might’ve helped.

Who names Clark Superman? Pa Kent (Ed Cassidy). “Your unique abilities make you … a kind of super man,” he says.Who designs his costume? Ma Kent (Virginia Carroll). “Here’s a uniform I made for you out of the blankets you were wrapped in when we found you,” she says. How does Kal-El learn about Krypton? From a Prof. Leeds, who shows him “a fragment from the planet Krypton, which exploded many years ago.” How does Leeds know about Krypton? How does he know it was called Krypton? Silence. When the fragment causes Clark to faint, Leeds immediately makes the connection between Clark and Superman. Actually, no. But Clark tells him anyway:

For years I suspected that I came to Earth from the planet Krypton. And now this meteorite seems to prove that. It takes away all my powers that make me superior to Earth men.

In truth, this is why you watch 65-year-old serials like “Superman.” For the historic record. To see how we interpreted the Man of Steel back then. To see what we valued.

The modern Superman would never call himself superior to anyone, let alone “Earth men,” but this Superman, only 10 years removed from Action Comics #1, was still a bit of a roughneck, and he still acquires his powers, not from the yellow sun, but from a civilization so far advanced it “boasted a race of super men and women.”

In this way the serial is an odd mix of pre- and post-WWII attitudes. A genetically superior race? Sounds like Nazi-era eugenics. At the same time, the lessons of the gas chambers are apparent in the peptalk Pa Kent gives young Clark about what he must do with his great powers. He must use them, he says, to fight for “truth, tolerance, and justice.”

Interestingly, all of the above attitudes, both pre- and post-WWII, would soon be gone from the Superman mythos. Yellow-sun mythology replaced genetic superiority, while “tolerance” never again turned up as something Superman fought for. It was replaced, famously, or infamously, by “the American way,” for the TV series, “The Adventures of Superman,” which debuted in 1952: the coldest part of the Cold War. We were a less-tolerant society by then. Tolerance had a small window.

Early CGI.

The mysterious reducer ray

The plot is typical of the serial genre. The Spider Lady, who never once leaves her mountainside lair with its electrified spider-web in the background, wants the mysterious reducer ray, “a force more powerful even than the atomic bomb.” Basically it’s a big ray gun. You feed it coordinates and it can destroy a target thousands of miles away. Why does the Spider Lady want it? Probably to rule the world. How is she going to get past Superman to get it? She has a chunk of kryptonite. Why is it called the reducer ray when it doesn’t reduce anything? Uh…

First she tries to steal it. No go. Then she employs Dr. Hackett, “a brilliant scientist with a warped mind,” who invents a kind of kryptonite gun. That doesn’t work, either. Then she kidnaps Dr. Graham, the original inventor of the reducer ray, and forces him to create a second reducer ray. He refuses. After he’s tortured, he complies. But he needs mono chromite. It takes a few chapters to get that. At which point he refuses again. So he’s hypnotized into complying. But now he needs an “activator tube” from Metropolis U. That takes a while. By Chapter 14, the reducer ray finally works. The Spider Lady’s first target? Her own men in jail. Her second target? The Daily Planet building. At 3:00. By then, though, everyone converges on her lair: Jimmy, Lois and eventually Superman, weakened by kryptonite. But not! Up he pops with a big smile.

Spider Lady: Superman, you didn’t succumb to the kryptonite!

Superman: I expected you to have it handy so I’m wearing a protective lining of lead under my uniform. What you thought was my weakness turned out to be your undoing! Spider Lady, you’re finished!

And she is. When she tries to run away, she’s electrocuted by her own spiderweb. Crime don’t pay, kids.

As for Clark? Why, he’s asleep at the Daily Planet.

Clark: Oh, I was just having a wonderful dream.

Lois: You weren’t dreaming by any chance that you were Superman?

Clark: That’s exactly right, Lois. And I was flying through the air.

Lois: That wasn’t a dream, Kent. As far as I’m concerned, that’s a nightmare.

And everyone laughs. The end.

In truth, this is why you watch 65-year-old serials like “Superman.” To see what passed for entertainment back then.

Superman, Lois and Jimmy watching the Spider Lady fry.

Metropolis R.F.D.

I have to admit, I liked, well enough, Alyn’s performance. He’s got a dancer’s lightness to him and a perpetual gee-whiz expression on his face, as if he too is amazed by the things he can do. He also has an early version of the spitcurl. Yes, at times, particularly employing his x-ray vision, he looks slightly crazed. Plus he’s undone, certainly to modern eyes, by the lack of special effects. His big stunt is taking two crooks and bonking their heads together. He can never win a fight as Clark Kent, either, and it hardly seems a matter of protecting his secret identity. No, he just can’t fight. He gets knocked down and has to shake the cobwebs from his head. It’s as if he’s not super until he removes his suit and tie.

Another positive: In the 1940s Batman serials, the cliffhangers tend to involve the heroes caught in some predicament, which means they have to get in some predicament, which means, in almost every episode, they have to lose a fight. Some dynamic duo. In “Superman,” most of the cliffhangers involve Superman’s friends: Lois, Jimmy, Perry. Each cliffhanger is less about Superman than a job for Superman. Alyn says the line throughout the serial, too, following the Bud Collyer model from the radio show by deepening his voice on the final words: “This looks like a job … FOR SUPERMAN!” It’s a conceit that continued into the 1960s.

Lois? Forever involved in machinations to prevent Clark from scooping her, even though these machinations invariably imperil herself, Jimmy, Clark, and, since we’re talking the reducer ray, the entire planet. This is not a good Lois. She’s pouty and unclever and sexless. She’s like a Shirley Temple character who grew into her late 20s less cute than she used to be, less clever than she used to be, more annoying than she used to be. And could you give us a smile? Apparently this was obvious even back then. Two years later, for the 1950 sequel, “Atom Man vs. Superman,” Neill’s Lois smiles so much she seems like a Miss America contestant.

Jimmy? Unfunny comic relief. The Jughead of the crew. Perry? Never leaves his office. He’s like the Spider Lady in this regard. The entire serial could be seen as a battle between these two stationary entities who send their forces into the world to do battle.

That world is Metropolis but it seems more small town than big city. The local jail is like Andy Griffith’s, and they’re never too far away from a mine or a cave. When we finally see a map of Metropolis, hanging in the Daily Planet office, it’s an upside-down dog. That’s a clue, by the way.

Superman (Kirk Alyn) using his x-ray vision

So whatever happened to…?

The Spider Lady, meanwhile, has no spiders, wears a long black dress, and for a time, and for no discernible reason, a mask. What’s the source of her power? Who knows? She’s not strong, she’s not smart, she doesn’t use sex as a weapon. Her henchmen are lugs from central casting.

Basically she’s a ripoff of another Forman villainess, Sombra, the Black Widow, from the 1947 Republic serial “The Black Widow.” Was she typecast? A year after “Superman,” Forman played Nila, an Abistahnian criminal going up against Inspector David Worth (Alyn again), in “Federal Agents vs. Underworld, Inc.” Two years after that, in the Columbia serial “Blackhawk,” she played Laska, leader of an underground gang, who is foiled by … wait for it … Kirk Alyn. If TV hadn’t killed serials, these two might have kept going in perpetuity.

As it was, Forman was basically done by ’52, Alyn didn’t last much longer, and Tommy Bond moved over into the prop department for TV shows like “Laugh-In” and “Sonny and Cher.” Neill, meanwhile, who played the third-year girl who gripes Gene Kelly’s liver in “An American in Paris,” essentially made a career out of the Superman franchise. She played Lois for most of TV’s “The Adventures of Superman,” had a bit part as Lois’ mom, Ella, in the extended cut of “Superman: The Movie” (1978), shows up in “The Adventures of Superboy,” and even played Gertrude Vanderworth, the wealthy widow bilked of her money by Kevin Spacey’s Lex Luthor in “Superman Returns” (2006).

Might as well. Movie serials may have been dying but superhero films were just beginning to fly.

The opening credits. Serials were about to die; superhero movies were not.

Friday February 18, 2011

Charters and Caldicott and the “Night Train to Munich” (1940)

The other night Patricia and I were watching a not-bad film from 1940: Carol Reed's “Night Train to Munich,” starring Margaret Lockwood and Rex Harrison. Not sure why I rented it. Probably Carol Reed.

After the German takeover of Czechoslovakia, the Allies manage to secret out of the country an inventor of a better kind of armour plating, Axel Bomasch (James Harcourt), but his daughter, Anna (Margaret Lockwood), still veddy veddy British, is captured and placed in a concentration camp. There she encounters a dashing freedom fighter, Karl Marsen, played by Paul Henried, who, two years later, would play the most dashing freedom fighter of them all, Victor Laszlo in “Casablanca.” Even so: knowing it was still early in the film, knowing Lockwood's true co-star was Rex Harrison, and seeing that Henried was billed as Paul von Hernried, I thought, “He's a plant. He's a spy. To get to her father.” As he was. As they did: secreting him and daughter back out of Britain and to Germany just before Sept. 1, 1939.

After the German takeover of Czechoslovakia, the Allies manage to secret out of the country an inventor of a better kind of armour plating, Axel Bomasch (James Harcourt), but his daughter, Anna (Margaret Lockwood), still veddy veddy British, is captured and placed in a concentration camp. There she encounters a dashing freedom fighter, Karl Marsen, played by Paul Henried, who, two years later, would play the most dashing freedom fighter of them all, Victor Laszlo in “Casablanca.” Even so: knowing it was still early in the film, knowing Lockwood's true co-star was Rex Harrison, and seeing that Henried was billed as Paul von Hernried, I thought, “He's a plant. He's a spy. To get to her father.” As he was. As they did: secreting him and daughter back out of Britain and to Germany just before Sept. 1, 1939.

Ah, but intrepid agent, Gus Bennett (Harrison), seen to this point mostly as a boardwalk barker, decides to go to Berlin undercover, as Major Herzoff, monocle and all, to get father and daughter back.

I should add that I'd never seen a youthful Rex Harrison before and was fairly blown away. The movie felt run-of-the-mill until he came onscreen and then: zap! That Henry Higgins persona is already there: distant, faintly amused by it all, protected with a kind of armour plating of his own that still allows his charm-for-charm's-sake to seep through. He has a kind of flirtatiousness with women but it's wrapped in a challenge that's intellectual and dismissive rather than sexual and complimentary. “Do you have any brains at all?” he seems to be saying. “Let's see, shall we?”

At one point Lockwood and Harrison are having a great back-and-forth in her swanky bedroom in Germany, going over the escape plan. It's not much of an escape plan. He'll say he persuaded her to persuade her father to stay and work for the Germans, and while the high command is congratulating themselves they'll all make their escape via airplane in a nearby field.

Anna: But why should the admirality believe you persuaded me?

Gus: I shall indicate that once again you have succumbed to my charms.

Anna (aghast): Once again?

Gus: (pleased with himself) It happened in Prague, I'm afraid.

Anna: And you told them a fantastic story like that?

Gus: Fantastic? It was four years ago, there was a harvest moon, I was younger and more dashing then...

“It happened in Prague, I'm afraid.”

“Night Train to Munich” is amazingly light for a film about Nazis produced as bombs were raining down on London. Stiff upper lip and all that. They make jokes about Nazi propaganda:

“Any day now,” a Nazi officer says at one point, “Poland may provoke us into invading her in self-defense!”

There's an extended piece with two Germans that, between “Heil Hitlers,” is simply wordplay:

Kampenfeldt: It's been reported to me that you've been heard expressing sentiments hostile to the fatherland!

Schwab: What — me, sir?

Kampenfeldt: I warn you, Schwab, this treasonable conduct will lead you to a concentration camp.

Schwab: But, sir, what did I say?

Kampenfeldt: You were distinctly heard to remark, [sarcastic] “This is a fine country to live in.”

Schwab: Oh no, sir. There's some mistake. What I said was, [upbeat] “This is a fine country to live in!”

Kampenfeldt: You sure?

Schwab: Yes, sir.

Kampenfeldt: I see. Well in future don't make remarks that can be taken two ways.

Both Kampenfeldt and Schwab are even less German than Rex Harrison That's part of the fun of watching cinema from other countries. Everyone does it as badly, as myopically, as Hollywood.

Following the titular train to Munich, we see, at a German train station, a man asking for a copy of “Punch,” the British humor magazine. Me to Patricia: “OK. They're not trying to pass that guy off as German, are they?” They're not. The man is British. He's frightfully put off, for example, that the Germans don't carry this week's “Punch,” and both he and his companion seem completely oblivious to the danger they're in as British nationals in Nazi Germany after Sept. 1st. Which is about when the other shoe dropped.

“Wait a minute,” I said to Patricia. “Aren't these guys the same guys from 'The Lady Vanishes'?” A second later: “I think they're playing the same characters.”

Charters and Caldicott: Terribly put out in the midst of this how-do-you do.

I'm probably the last movie critic in America to know this story. Charters and Caldicott are two obtuse, cricket-obsessed British characters, played by Basil Radford (Charters) and Naunton Wayne (Caldicott), who made their first appearance in Hitchcock's “The Lady Vanishes. They proved so popular with British crowds that screenwriter Sidney Gilliat, who had written a good half-dozen screenplays since ”The Lady Vanishes“ in '38, resurrected them for ”Night Train to Munich“ in 1940, then for ”Millions Like Us,“ about a British factory girl, in '43. They were given the lead in ”Crook's Tour“ in '41, but Gilliat wasn't involved in that project.

Apparently the actors had a falling out with Gilliant in '45 when he refused to expand their roles for ”I See a Dark Stranger“ and they walked, both away from Gilliat and the names, but not from each other. In subsequent films they played similarly self-regarding characters with different names: Prendergast and Fotheringham in ”A Girl in a Million“ (1946), Gregg and Straker in ”Passport to Pimlico“ (1949) and Bright and Early in ”It's Not Cricket.“ Radford died in 1952, Wayne in 1970, but the characters returned in a 1979 remake of ”The Lady Vanishes,“ and then on the BBC for a eponymous 1980s television series.

How well known are they? I mentioned all this to a friend at a party recently, American but an Anglophile, and when I had trouble coming up with the names he provided them. Is there an American equivalent? Abbot and Costello maybe? But they were stars, known by their own names. Statler and Waldorf maybe? Muppets. Could you do American versions of these characters? They'd probably have to be baseball fans. Football fans seem too Paul Fistinyourface to allow for C&C's dry humor:

Charters: Bought a copy of ”Mein Kampf.“ Appears to me it might shed a spot of light on all this how-do-you-do. Ever read it?

Caldicott (sucking on a pipe): Never had the time.

Charters: I understand they give a copy to all the bridal couples over here.

Caldicott: Why, I don't think it's that sort of book, old man.

Not that sort of book, old man.

In ”Night Train,“ Caldicott recognizes Major Herzoff as Dickie Randall (Gus's real name), who used to play for the Gentlemen, a cricket club, and his questions rouse the suspicions of Karl Marsen, who's already jealous of Herzoff's apparent hold on Anna. Eventually, through the fog of their British obtusness, Charters and Caldicott realize they've put old Dickie in a bit of a spot and come vaguely to his rescue. There's a car chase, then a tramway adventure high in the Alps, but everyone makes it safely to Switzerland, where Dickie falls into Anna's arms, and, one imagines, Bomasch's armour plating helps win the how-do-you-do and Charters and Caldicott finally, finally get their copy of ”Punch."

Tuesday November 16, 2010

Review: “Notorious” (1946)

WARNING: KEY SPOILERS

Alfred Hitchcock’s “Notorious” is the greatest love story ever filmed between a cold bastard and a drunken whore.

That’s a joke and it isn’t. There’s the story we watch and there’s the way Hitchcock undercuts the story we watch. He smuggles all sorts of shit in. He gets America, this puritanical country, to care about these less-than-pure people.

That’s a joke and it isn’t. There’s the story we watch and there’s the way Hitchcock undercuts the story we watch. He smuggles all sorts of shit in. He gets America, this puritanical country, to care about these less-than-pure people.

The Hays code helped. In the first five minutes we learn that Alicia Huberman (Ingrid Bergman), whose father was recently convicted as a Nazi spy, drinks too much and sleeps around, but we only see her drunk once, and we never see her sleeping around—just flirting with Cary Grant, who, let’s face it, is Cary Grant, the Man from Dream City, etc., so who can blame her. The Hays code, by keeping Alicia’s more notorious activities discreet, keeps her sympathetic. When others bring up her past, it almost seems unfair, as if they were tarnishing her with rumors rather than agreed-upon facts.

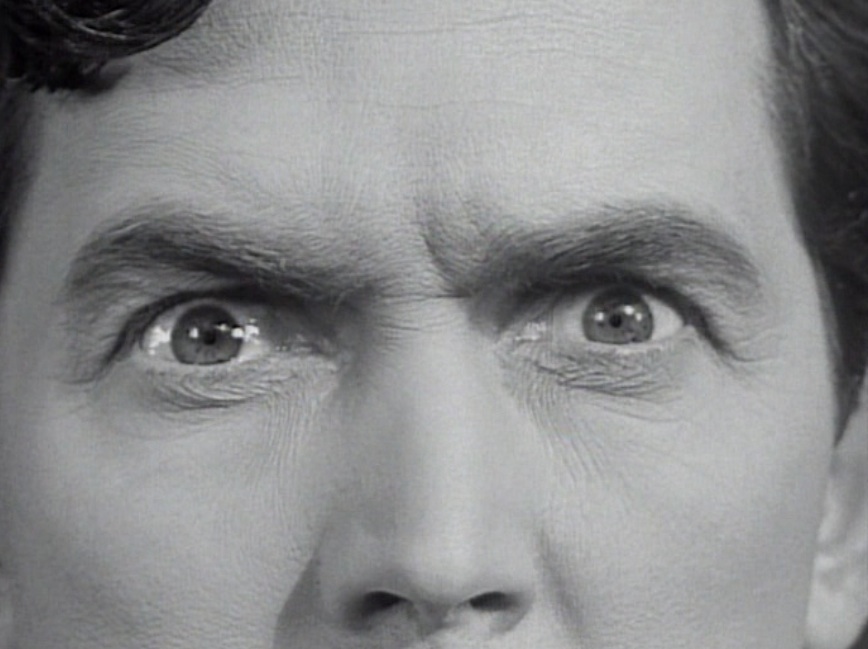

As for the cold bastard? We first see Devlin (Grant) as the back of a head and wonder, “Why is Hitchcock filming the back of his head when the front of his head has Cary Grant’s face attached to it?” Answer: This is a man who reveals little. He’s a secret agent, CIA, OSS, or whatever the agency was between World War II and the passage of the National Security Act of 1947. He doesn’t talk much but every third word is sneered. It takes a lot to drain the charm out of Cary Grant but Hitchcock does it masterfully.

The greatest romance of all time!

The linchpin of the film is also masterfully, intricately created. Devlin recruits Alicia, this wanton, daughter-of-a-Nazi-spy, for an assignment in Rio de Janeiro, but before they get the assignment they fall in love. He loosens up and she looks like Ingrid Bergman again. It begins to feel like a traditional Hollywood romance. There’s even a famous two-and-a-half minute kissing scene that, by skirting the Hays’ code’s admonition of kisses longer than three seconds, relies on multiple, nibbling pecks, making it even sexier than if they’d been allowed to slobber all over each other.

Then the assignment arrives. She’s to infiltrate a gang of Nazis by throwing her charms at one of the leaders, Alexander Sebastian (Claude Rains), who once had a crush on her. And by “throwing her charms at,” I mean “sleeping with.” Or “fucking.” All of which is discreetly implied with words like “playmates.” Hays Code to the rescue again.

So Devlin is torn. He’s a professional man but also a man in love. The man in love wants her to say “no” but the professional man knows the job is the job. Which side wins? The side that says nothing. He gets even more tight-lipped. Just when she wants him to talk.

She’s a woman in love but an amateur in this profession, so she goes along with the scheme, one can argue, for Devlin. He wants her to say “no,” but she says “yes” for him. Talk about cross purposes.

That’s how Hitchcock undercuts the traditional Hollywood romance. But “Notorious” is also a thriller, a post-WWII thriller about American agents battling South American Nazis, and the way he undercuts the film’s ostensible patriotism is even more brilliant.

Three scenes stand out.

In the first scene, early in the movie, Devlin recruits Alicia, not by appealing to her patriotism, but by revealing how patriotic she already is. Three months earlier, her father tried to recruit her to the German cause and she’d responded with a speech, straight out of a war-bonds fundraiser, about how much she loves America. Most of us reveal our best face to the world while doing what we do in private. She, apparently, is the opposite.

And how does Devlin remind her how patriotic she is? By playing a recording of that conversation with her father. The very government she’s defending on that recording, in other words, is in fact recording her. It’s spying on her. By showing her that she’s patriotic, he’s also showing her why she shouldn’t be patriotic.

Her secret shame: patriotism.

All of which goes unsaid. The second scene, halfway through the movie, is more overt.

By this point Alicia has infiltrated Sebastian’s sanctum at great risk and personal loss—she loses Devlin—but here she’s about to turn up at agency headquarters, and the man in charge, Capt. Paul Prescott (Louis Calhern), worries. Another one of the higher-ups, Walter Beardsley (Moroni Olsen) adds, “She's had me worried for some time. A woman of that sort.”

During this conversation, Devlin had been showing us the back of his head to the room, but Beardsley’s remark literally turns him around. It forces him to reveal his true face:

Devlin: What sort is that, Mr. Beardsley?

Beardsley: Oh, I don't think any of us have any illusions about her character, have we, Devlin?

Devlin: Not at all. Not in the slightest. Miss Huberman is first, last, and always not a lady. She may be risking her life, but when it comes to being a lady, she doesn't hold a candle to your wife, sir, sitting in Washington, playing bridge with three other ladies of great honor and virtue.

Wow.

Hitchcock, of course, grew up in working-class London and maintained working-class suspicions of the oligarchy. There are people who work and people who don’t. There are soldiers and those who order soldiers into battle. Alicia, at this point, is a soldier. These old men and their wives who look down upon the Alicias of the world? Not. They call into question her character but Hitchcock, through Devlin, calls into question their character, and all they can do in response is be affronted:

Beardsley: I think those remarks about my wife are uncalled for.

Devlin (unapologetic): Withdrawn. Apologized, sir.

The men who do little.

The man who reveals little.

His true face. “Withdrawn. Apologized, sir.”

The third scene, near the end of the film, may be the strongest of the lot.

By this point, Alicia has actually married Sebastian and is living in his mansion with his domineering mother, whom he calls “Mother,” prefiguring Norman Bates by 15 years. At a party to introduce Alicia to Rio society, Alicia and Devlin discover the Nazis secret: ore, most likely uranium ore, hidden in wine bottles in Sebastian’s basement. It’s Hitchcock’s McGuffin, but unlike most McGuffins it’s not harmless. It actually anticipates (in the writing and filming) the A-bomb, which will transform the world.

To discover this, Alicia has to steal the wine-cellar key, a Unica key, from hubby’s keyring. Unfortunately, he notices it’s gone, then notices it’s back, and in the wine cellar he finds jig-is-up evidence of Devlin’s clumsy snooping. “I’m married to an American agent,” he tells Mother. But what to do? Killing an American agent can’t make up for having married her in the first place; that won’t sit well with the other Nazis, who, remember, killed poor Emil Hupka (Eberhard Krumschmidt—his only role in movies!) simply for having a lousy poker face.

So Mother concocts a scheme to slowly poison Alicia. It will seem, to the other Nazis and the rest of the world, as if she had an illness and expired. Alicia figures it out, but too late, when she’s too weak to do anything about it, and she’s led, as if in a nightmare, up to her bedroom, where Mother, with her thick German accent, says, “We’ll take the best care of her,” and Sebastian, feigning concern (and with the camera zooming in tight on Alicia’s helpless, stricken face), tells the butler, “Josef, disconnect the telephone, Madame must have absolute quiet. Take it out of the room.”

Creepy.

Then, in rapid succession, we see:

- Devlin sitting on a park bench, his meeting place with Alicia, looking at his watch.

- Alicia in bed, dying. Mother off to the side, knitting peacefully.

- Devlin, at night, pacing before the same park bench.

In our minds we’re going “Hurry! Hurry!” and finally we get a meeting between Devlin and Prescott. Most such meetings took place in Prescott’s office but this one is in Prescott’s hotel room. It indicates how worried Devlin is. He, like us, can’t wait for tomorrow.

The hotel room also allows Hitchcock to juxtapose Alicia, the solider, with Prescott, the general.

Like Alicia, Prescott is lying in bed. Unlike Alicia, he’s a picture of health. In fact, as Devlin reveals his concerns, and as we’re still shouting “Hurry!” in our minds, Prescott nonchalantly, infuriatingly, butters crackers and stuffs them in his face.

“Five days, eh?” he says, unconcerned. “That must be quite a binge she’s on.” Devlin figured the same—Alicia had lied to him about her sickness—but now he’s having second thoughts. Prescott has none. He even warns against Devlin checking up on her since he doesn’t want anything to jeopardize the mission. Then he picks cracker crumbs off his chest.

“That must be quite a binge she's on.”

How far will you go for love or country? That’s one of the main dilemmas of the film. Love doesn’t do poorly in this equation, since, in the end, Devlin comes through, despite Alicia’s past, despite Alicia’s assignment. But country? Beardlsey represents the country. He thinks poorly of the workers. Prescott represents the country. He can’t be bothered to get out of bed. While Alicia is dying in hers.

There is, in general, great balance in “Notorious.” In one of the first shots, we see the judges and executioners of Alicia’s father framed in a doorway; and in one of the last shots, we see the judges and executioners of Alicia’s husband framed in a doorway. After Alicia is reintroduced to Sebastian, we see Devlin sitting alone at a restaurant on the left side of the screen. In the next shot, we see Alicia sitting alone at a restaurant on the right side of the screen. Balance.

But there is no balance as to our loyalties. The film’s second-most famous shot, after the kissing scene, occurs at the beginning of the party, when the camera, starting from the upper floor, sweeps down to focus on the Unica key in Alicia’s nervous hand. It’s a great shot. One can’t help notice, too, the checkerboard pattern on the floor, and how all of the guests, milling about, look like pieces in a chess game. Which they are. That isn’t a point of contention. Our problem is with the men moving this particular piece. They don't know its value. They see a pawn. We see the queen.

Saturday June 21, 2008

Movie Review: The Batman (1943)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The chief problem with this 15-episode serial, the second live-action version of a modern superhero, isn’t the low-budget effects (Columbia serials were notoriously cheap), nor its racism (the chief villain is a Japanese spy during WWII), but the form itself, the serial form, which requires cliffhanger endings for its heroes. Since the lives of Batman and Robin (Lewis Wilson and Douglas Croft) hang by a thread at the end of every episode, and since the serial wasn’t budgeted for a lot of extras, “America’s greatest crimefighter,” as Batman is called in the narrative intro, isn’t that great a crime fighter. Among the cliffhangers:

- Two crooks throw Batman, arms and legs thrashing, off a roof.

- Three crooks toss Batman. arms and legs thrashing, down an elevator shaft.

- A crook throws a stick at Batman’s head, knocking him unconscious.

- A gangplank is dropped on him.

- He drives a car off a bridge.

- He gets trapped by a fire he sets.

We keep seeing Batman getting outpunched by one or two criminals. I’m talking ordinary guys in suits and fedoras. What’s the point of putting on cape and cowl if you can’t take one guy?

Everything but the kitchen sink

The serial begins well enough. The credits play over the famous bat logo (human head on bat body), while the ominous theme music (Wagner’s Rienzi Overture?) prefigures Danny Elfman’s from the 1989 version. Even the first shot of the Bat’s Cave, as it’s called here (it was, in fact, introduced here), is cool. Batman sits brooding behind a desk of finely engraved oak while shadows of bats play against the wall.

The serial begins well enough. The credits play over the famous bat logo (human head on bat body), while the ominous theme music (Wagner’s Rienzi Overture?) prefigures Danny Elfman’s from the 1989 version. Even the first shot of the Bat’s Cave, as it’s called here (it was, in fact, introduced here), is cool. Batman sits brooding behind a desk of finely engraved oak while shadows of bats play against the wall.

Then the cheapness. Once the background narration ends, and the story proper begins, we see a plain black Cadillac pull up to a police phone, and out pop...Batman and Robin! So no Batmobile. Batman phones Capt. Arnold (no Comm. Gordon) and tells him, in a vaguely British tone, “I have a nice little package for you. You’ll find it at the corner of First and Maple.” He leaves the crooks handcuffed to a light pole with bat stickers on their foreheads — his version of Zorro’s “Z” — and then he and Robin drive off, Robin behind the wheel, and the two take off their masks and smile.

The plot? Dr. Tito Daka, a Japanese spy whose headquarters lie through a secret panel in the Japanese Cave of Horrors in deserted Little Tokyo, wants to secure enough radium for an “atom-smasher gun” that will bring America to its knees. In this regard he employs disgraced scientists and various hoodlums to carry out his orders. If they balk (“No amount of torture, conceived by your twisted Oriental brain, can change my mind!” says one scientist), he simply turns them into super-strong zombies. It’s part of the “everything but the kitchen sink” quality that, you imagine, everyone hoped would appeal to 10-year-old boys in 1943. Hey, kids! Not just Batman and Robin but spies and zombies and alligators and invisible messages from Washington, D.C.!

The writers, poor bastards, do manage to display some postmodern wit by commenting upon the very low quality of their product. Two American mechanics, encountering Daka in the Japanese Cave of Horrors, think he’s part of the program. “Pretty good, Saki,” one says. “Your accent’s a bit off but your makeup’s perfect.”

Better, they slip in a comment about the repetitive nature of the genre itself. Daka’s minions keep trying to steal the necessary radium for the atom-smasher gun and Batman and Robin keep foiling them. So the focus becomes less on acquiring radium and more on getting rid of Batman. Because of the cliffhangers, they assume they do at the end of every episode, which leads to conversations like this at the beginning of every episode: “We didn’t do the job, boss, Batman stopped us.” “Batman? He’s still alive?” “Yeah, but we killed him this time for sure!”

Eventually Daka decides that Batman can’t keep escaping death this way; that there must be many Batmen, “all members of the same organization,” he says. It’s not a bad bit.

A wise government

But these days Batman '43 is most compelling as historical document — particularly on the subject of race. In one episode, Bruce Wayne says of a friend, “Why, I haven’t seen Ken in a coon’s age!” In another, we get an Indian full of “Him say...” “Me say...” dialogue.

Daka is played by a Caucasian actor, J. Carrol Naish, nominated for an Academy Award that very year for playing the Italian, Giuseppe, in the Humphrey Bogart vehicle Sahara, and who would, during his career, play every conceivable ethnicity — from Sitting Bull in Sitting Bull (1954) to Charlie Chan in the 1950s TV series “The New Adventures of Charlie Chan” — but he’s hardly brilliant here. Those American mechanics were right about the accent. He sounds like Peter Lorre by way of Brooklyn.

Of course given Pearl Harbor, and Hollywood’s track record with stereotypes before Pearl Harbor, one expects the giggling sadism and the unapologetic “So sorry” comments from Daka. One isn’t particularly surprised when a crook, turning against Daka, tells him, “That’s the kind of answer that fits the color of your skin!” One even laughs when Bruce Wayne’s girlfriend, Linda Page (Shirley Patterson), encounters Daka and yelps, “A Jap!”

The eye-opener is what bookends the serial. In the first episode, when we first visit Little Tokyo, the narrator informs us:

This was part of a foreign land, transplanted bodily to America, and known as Little Tokyo. Since a wise government rounded up the shifty-eyed Japs it’s become virtually a ghost street...

In the last episode, Batman, pinned in Daka’s lair by his zombies, mentions, out of the blue, “I know who you are. We’ve been searching for you ever since you killed those two agents assigned to your deportation!” Thus the entire serial is painted with the wisdom of deportation and internment camps. See what happens when you don’t round up the shifty-eyed Japs? Decades later, the internment of Japanese-Americans became a source of national shame but at its point of origin it was triumphant enough to include in serials for children.

The original VHS release excised these slurs but they’ve been restored for the DVD version. Good. It's important to know where we've been. Otherwise how can we see how far we've come?

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)