Movie Reviews - 1950s posts

Tuesday July 21, 2020

Movie Review: Love Me or Leave Me (1955)

One, two, three for Cagney: First Cinemascope, second-billed, third Oscar nom.

WARNING: SPOILERS

There’s a line near the end of this that made me laugh out loud. At the grand opening of a nightclub, “M.S.,” its proprietor and namesake, Marty Snyder (James Cagney), steps out of a car and is arguing with a friend when a young autograph hound spies him and shouts: “Hey, that’s the guy that shot the guy!”

That is so good. Is it based on anything? A famous Hollywood story? Or did it come from the imaginations of screenwriters Daniel Fuschs and Isobel Lennart? Or director Charles “not King” Vidor? I’m finding nothing online. Anyway, it was the best line in the movie.

A lot of firsts and lasts with this one. Released in June 1955, “Love Me or Leave Me” was Cagney’s first Cinemascope picture; it was the first time he was second-billed since the 1930s (apparently at his insistence), and it garnered him his third and final Oscar nomination for lead actor. (He lost to another Marty: Ernest Borgnine.) It was a huge hit—the eighth-biggest of the year—while its soundtrack was the No. 1 album in the country for six months: from early August to late January 1956. (It was replaced by “Oklahoma!,” which was replaced by “Belafonte,” which was replaced by … wait for it … “Elvis Presley.” And now you know the rest of the story.)

“Love Me or Leave Me” was also the second-to-last time Cagney played a gangster, and he may never have been scarier. Imagine Cody Jarrett hopelessly in love. The movie is based on a true, tempestuous love story that Hays-Code Hollywood probably couldn’t tell properly, so, in between socko Doris Day numbers, they made it about an abusive relationship. It doesn’t mesh. It’s kind of exhausting, actually.

Mean to me

Background: Singer Ruth Etting said she married gangster Moe “The Gimp” Snyder “9/10 out of fear and 1/10 out of pity.” She feared that if she left him, he would kill her.

Cagney’s Marty has elements of the real Moe, but Ruth has been cleaned up. From IMDb:

Ruth Etting was a kept woman who clawed her way up from seamy Chicago nightclubs to the Ziegfeld Follies. It would require her to drink, wear scant, sexy costumes and to string along a man she didn't love in order to further her career. There was also a certain vulgarity about Etting that she didn't want to play. Producer Joe Pasternak convinced Day to accept the role because she would give the part some dignity that would play away from the vulgarity.

Except Ruth’s lack of vulgarity makes the abuse seem worse. Day’s dignified Ruth is a declawed cat being messed with by a junkyard dog. One yearns to see the claws come out.

In 1920s Chicago, Etting is a dime-a-dance girl who doesn’t like men who paw at her, which is all of them, so she’s fired. Snyder, shaking down the proprietor, takes a shine and uses his connections to get her singing gigs, expecting some quid for his quo, but she keeps putting him off. Until he’s tired of being put off. But even then nothing comes of it. In her dressing room, he says he’s stuck on her, she says she’s not on him, not yet anyway (that’s the lie), and the higher she rises the more jealous he becomes: of potential rival agents and potential rival lovers—like that piano player Johnny Alderman (Cameron Mitchell), with cheekbones like diamonds.

Up the ladder she goes: from singing, to headlining, to radio, all the way to New York City and the Ziegfeld Follies. For the real Etting, that was 1927 and she’d been married to Snyder for five years; here, they haven’t even kissed. Opening night at Ziegfeld, Marty rushes backstage during the middle of her performance, has his way blocked, decks a tall guy (as Cagney is contractually obligated to do), and is hustled out, huffing and puffing, between two other guys. Back at her hotel room, we find out he’s particularly mad at her for not sticking up for him. “You walked away!” he shouts. He talks about the debt she owes him but she says there’s no way she can pay it off. “Ain’t there?” he cries, then throws her down on an ottoman and kisses her. She stumbles away, in tears.

This was supposed to be a rape scene, believe it or not. According to IMDb, “As originally filmed, Cagney slammed her against a wall, savagely tore off her dress, and after a tempestuous struggle, he threw her onto a bed and raped her.” Can’t quite see that happening in a 1955 movie, but its removal means after one kiss she’s suddenly undone—lifeless. She marries Marty, quits Ziegfeld, tours with Marty. He tells her he’ll take care of her, and, dead-eyed and dead-voiced, she responds: “You don’t have to sell me. I’m sold.” Great, sad line.

Eventually he lands her a gig in Hollywood. Guess who’s there? Johnny Alderman of the cheekbones. He’s musical director for the movie she’s working on, Marty doesn’t like it a bit, and for some reason she chooses this moment to fight back.

Snyder: That’s the way with those phonies: You gotta let ’em know who ya are.

Etting: Who are you, Marty?

Snyder: What do you mean?

Etting: What have you accomplished? Can you produce a picture? Have you done one successful thing on your own? Just who do you think you are?

Ouch. In front of her he makes a joke but behind the scenes he’s seething. His good-natured right-hand man, Georgie (Harry Bellaver), tries to make him feel better by saying he was a big man in Chicago but here they think Ruth’s his meal ticket. Doesn’t go well. Marty decks him. Then he gets an idea. He’ll open his own nightclub! That’ll make him a big man. Everyone else thinks it’s a lousy idea but now he’s too busy to hover around Ruth, so her romance with Johnny blossoms.

That sets up the rest. He tries to get Johnny fired from the movie, she objects, he slaps her, she leaves him for good. He assumes the worst: cheekbone dude. And he finds them in a doorway clinch. So he shoots him.

Shaking the blues away

One assumes some kind of comeuppance for all of Marty’s crimes but it doesn’t quite arrive. Because it’s based on a true story and MGM wanted everyone to sign on? Because Cagney’s fans needed to be placated? Marty is a monster, truly—by the end we’re as twitchy around him as Ruth—but after he’s bailed out on attempted murder charges he discovers that Ruth is actually headlining the opening of his nightclub. All his friends arranged it! And Ruth agreed to it! (She feels she still owes him.) All of which just pisses him off—it’s the meal-ticket thing—but eventually he calms down. And leaning against the bar at his brand-new nightclub, he takes it all in, while the girl he abused belts out the closing number for him.

And they all lived happily ever after.

Again, Day is fine if miscast; and while she’s got great pipes, the musical numbers have that hammy, Eisenhower-era cheerfulness at odds with everything else going on. Mainstream 1950s movies—selling Technicolor and Cinemascope and uplift—really were the worst.

Cagney, though, is great. I don’t know if he got the Oscar nom for the limp—you know how Academy voters are—but in those early confrontations there’s such a look of betrayal and contempt and anger in his eyes. He’s never not in this guy’s fucked-up worldview. It’s as if he got the limp from the massive chip on his shoulder.

This is third time Cagney played a ’20s gangster—“The Public Enemy” in 1931 and “Roaring Twenties” in 1939—and we get other echoes from Cagney pictures, too. Setting up his club, isn’t it a bit like Bat setting up his bar in “Frisco Kid”? Marty doesn’t speak Yiddish but he does get off a “Mazel tov” before Ruth headlines her first show. And I don’t know if this was intentional or not—if the phrase was already in the cinematic lexicon—but before her first show, Ruth asks the piano player, Johnny of the cheekbones, how she looks. His reply? “Top of the world.”

Thursday May 21, 2020

Movie Review: Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye (1950)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The most famous cinematic gangster of the 1930s hardly played one in the 1940s. In that decade, James Cagney played a pilot twice, a reporter twice, a spy chief, a dentist, a “barroom observer,” and of course George M. Cohan, but never the kind of lawless SOB that made him famous. It wasn’t until William Cagney Productions lost a bundle on its adaptation of William Saroyan’s “The Time of Your Life” that Cagney returned to Warner Bros. and the type of role people associated him with: gangster Cody Jarrett in “White Heat” in 1949. That went well. A year later, Cagney Productions came out with its own Cagney gangster flick, “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye.” That went less well.

It’s still a fascinating movie. In fact, is it more fascinating?

“White Heat,” directed by Raoul Walsh, is the better film, and it’s modern in its T-Men crime methodology and Freudian mother-complex psychology. At the same time, it’s not exactly modern. What are our set pieces? A train, a cabin, a motel, a prison, another cabin, an oil refinery. We could’ve gotten variations of all of these 30 years earlier. Maybe even 50 years earlier? It’s a mid-20th-century movie that begins with a 19th-century crime: a train robbery.

Though “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye” starts in a chain-gang work farm, we get up-to-date quick. Some of it is startling to see—like James Cagney wandering the aisles of a modern, midsized supermarket in Glendale, Calif. But the most startling moment is when he visits a southern California “church.” It’s New Age before the term was coined. It’s “The Master” at the time of “The Master.” It may be the first instance of such a thing showing up in the movies. Cagney immediately mocks it, of course. He knew a grift when he saw one.

Peckinpah before Peckinpah

For a movie that was banned in Ohio for its “sordid, sadistic presentation of brutality,” “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye” begins like a bland 1960s TV courtroom procedural: crescendoing soundtrack music, close-up of a gavel being pounded, “Directed by Gordon Douglas.” This is Douglas’ only Cagney feature. He would go on to direct B-movies in the ’50s (“Them!,” “I Was a Communist for the F.B.I.”), and Rat Pack and faux-Bond movies in the’60s (“Robin and the 7 Hoods,” “In Like Flint”), before ending his career with “Viva Knievel!” in 1977. His work here isn’t bad. At least we get some nice shots. Or do we credit cinematographer Peverell Marley for those?

It didn’t take me long to dislike the district attorney (Dan Riss). Something pinched and bitter about him. His opening accusations are of a piece with the McCarthy era:

“Look at [the seven defendants] carefully, because they are your enemies and the enemies of every decent citizen. They’re at war with you—and always have been and always will be! Should they escape this time, the next victim may be you! Or you! Or you!”

One of the seven defendants is an attorney, “Cherokee” Mandon (Luther Adler), “now the shame of his profession,” the prosecutor proclaims, but Mandon seems oddly unconcerned. And in case you’re wondering, yes, Luther is Stella’s brother. He’s great—one of the best things in the movie: both corrupt and calm. Halfway through, as he’s cross-examined, we get this exchange:

Prosecutor: You formerly practiced law in this state.

Mandon: I have not yet been disbarred.

Prosecutor: Quite so. But I’m sure that such will be the case in the near future!

Mandon [turns to Judge, calmly]: Objection?

Judge: Sustained. The prosecutor will please remember that the prisoner is innocent until proven guilty. Such insinuations are singularly out of place.

Prosecutor: Yes, your honor.

Good god, I laughed. That’s brilliant. I even began to wonder if we were supposed to dislike the DA; if the movie wasn’t a bit subversive—attacking what it pretended to be upholding. The DA wasn’t the only one making insinuations during this period, after all. Production began in April 1950, just two months after Joseph McCarthy came to power with his charge that 205 known communists had infiltrated the State Department. Then there was the Hollywood blacklist, which began with HUAC in 1947—or even earlier, really, before the war, with the Dies Committee. Cagney himself was accused of having communist ties on the front page of The New York Times in August 1940. He was cleared six days later … on pg. 21. Sadly, no judge remonstrated his high-powered accusers. I have to wonder, too, about the casting of Ward Bond, the self-appointed right-wing cop for HUAC and the Motion Picture Alliance, as a corrupt cop. Inspector Weber claims to be doing good but he’s doing the opposite. As was Bond.

The trial is our framing device. Seven people—two cops, a prison guard, a garage mechanic, a lawyer, a driver and a blonde—are charged with murder or accessory to murder, and we’re made to understand that the eighth orchestrated it all but sadly isn’t there to face the music. Several take the stand and everything is in flashback. The guard begins, “Well, sir, I guess this all began about four months ago…” and we’re back at a chain gang/work farm, where Ralph Cotter (Cagney) and Carleton (Neville Brand) are planning an escape with a planted gun. But when the bullets start flying Carleton loses his nerve, and Cotter, with that Cagney sneer, kills him point blank.

Their accomplices include Carleton’s sister, Holiday (Barbara Payton), a tall blonde who is distraught when Cotter says her brother was killed “by the guards”; and “Jinx” Raynor, the driver, who quickly becomes Cotter’s right-hand man. Holiday becomes Cotter’s girl. That part is actually brutal to watch—even today. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was the reason for the Ohio ban.

It’s also a deviation from the novel. “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye,” by Horace McCoy was published in 1948 to much acclaim. Apparently Bogart wanted to make it into a movie but someone else bought they rights, and the Cagneys bought them from him. They changed a few things. There’s no framing device in the novel; it’s first-person and begins on the work farm. But the biggest change is to Holiday. In the book, she’s blonde and statuesque like Payton, but not exactly innocent. She’s bad, sexual and aggressive. It’s that Mickey Spillane fantasy. This is what happens in the novel on the day of the jailbreak—the day her brother is killed:

Holiday opened the door and I went inside. Before I had time to say anything, to look around, to even put down the newspaper I was carrying, she grabbed me around the neck, kicking the door shut with her foot, putting her face up to mine, baring her teeth. I kissed her, but not as hard as she kissed me, and then I saw that she was wearing only a light flannel wrapper, unbuttoned all the way down.

The movie makes her an innocent, and in doing so makes it all much, much worse. In the movie, Cotter insinuates himself into her apartment, refuses to leave, forces her to fix him a meal, then badmouths her brother. She throws a knife at him, which hits him handle side by the ear. (Her one bad-girl moment.) He shoots her a look, calmly walks over to the bathroom, dabs his ear with a wet towel, then whips her with it until she breaks down. Crying, she admits she’s lonely, so lonely, and succumbs to his power. It’s a Peckinpah moment before Peckinpah. For most of the rest of the movie, she’s basically his housewife without the ring.

A grapefruit in the face seems like a lovetap compared to all this.

The Master before “The Master”

One thing that is in the novel? That New Age church. Screenwriter Harry Brown basically used McCoy’s stuff almost verbatim.

They got there this way. First, Cotter robs a supermarket, kills the owner, then gets into it with Vic Mason (an excellent Rhys Williams), the gimpy mechanic who provided the original getaway car. Mason is angry they chose a joint just a block from his garage and sics the crooked cops on Cotter. But when Cotter realizes Weber is an inspector, he hatches a plan to record him in the midst of the shakedown—Jinx in the closet with an actual recording disc, like an old-fashioned LP. For some reason, he figures he needs a mob lawyer for the actual blackmail attempt, which is why they go to Darius “Doc” Green (Frank Reicher), a former accomplice of Jinx’s, who can point them in the right direction.

Except by this point Doc is onto a bigger scam. Here’s the sign outside his house:

Inside, in a small, cramped room with signs proclaiming LOVE, TRUTH and an ALL-SEEING EYE, a few dozen people in folding chairs listen attentively to an older man, Doc Green, droning on from Plotinus’ letters to Flaccus. There’s also a pretty brunette there, Margaret Dobson (Helena Carter), who turns out to be the spoiled, slightly crazy daughter of the most powerful man in the state, and who later gives the men a lift in her British sportscar. She’s trying to convert them—especially Cotter. “It’s a philosophy,” she says of Doc Green’s sermons. “It goes into the fourth dimension.” Cotter, amused, says the following when she asks him to the next meeting:

“Oh, I’d be a very bad influence. My vibrations would be positively pointless. You see, I don’t hold with the theory that the fourth dimension is either philosophical or mathematical. I think it’s purely intuitional. I don’t mean to start an argument or sound pretentious, but that’s the way I feel about it.”

Again, this is in 1950. In the movie, she calls Green “The Doctor” but in the book it's “The Master.” Seriously, anyone know of earlier portrayals of New Age-type religions in the movies? I was so happy when I came across this. I love culling such gems in generally forgotten films.

The scene at Doc Green’s also includes another subtle anti-HUAC dig. Cotter and Jinx just want the name of a lawyer from Green but he’s recalcitrant; he feels he’s put all that behind him. They’re persistent. This is the novel:

Cotter: You don’t want to be bothered with us anymore, do you?

Green: No.

Cotter: Then think of somebody.

And in the movie during the blacklist:

Cotter: You don’t want to be bothered with us anymore, do you?

Green: No.

Cotter: Then give us a name.

Naming names. So in tune with the times.

Another shtunk

My feelings about “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye” kept changing. It starts out ponderous and self-important—or, again, is it mocking such ponderous self-importance?—and the towel-whipping scene is way creepy. Then the machinations to blackmail Weber are involved and interesting. But does it lose itself? Cotter keeps pushing the envelope with everybody but there’s a lot of pots to stir: a secret marriage to Margaret against Mandon’s counsel; blackmailing Weber to take on a rival racketeer. At least it makes you wonder who’s going to finally get him. Crazy Margaret? Her powerful father? Inspector Weber? The rival racketeer? The cops catching up to him? Turns out it’s the all-but-forgotten Holiday—for his original crime of killing her brother. Watching, it felt like a let-down. In retrospect I kind of like it. Original sins catch up to us when we’re busy making other plans.

For his part, Cagney hated the film. From John McCabe’s 1991 biography:

“Guess what noble character I was called on to play? Another shtunk. I didn’t want to do it, but it was from a well-known novel by a hell of a good writer, Horace McCoy. In the novel the Cagney character is complex, interesting. He has a Phi Beta Kappa key, of all things, on top of which he was an ex-dancer. Not that you saw any of this in the picture. All the complex stuff was ironed out by the writer with the plea that there was no time for subtleties. He was probably right. Anyway, Bill said, ‘Jim, we need the dough, and it’s the last gangster I’ll ever ask you to play.’ He kept his word. I did play a few more rats after that, but no gangsters.”

The writer who had no time for subtleties was Harry Brown, who won an Oscar a year later for co-writing “A Place in the Sun” with Michael Wilson. Wilson was infamously blacklisted (and went uncredited on “Bridge Over the River Kwai”) but Brown kept working through the 1950s. Genre stuff, mostly: westerns, war. In the early ’60s he wrote “Ocean’s 11.” His life trajectory was basically: Maine, Harvard, Robert Lowell, poetry, 158-page epic poem called “The Poem of Bunker Hill,” Time, The New Yorker, WWII with Yank magazine (but unmentioned in Walter Bernstein’s memoir), then Hollywood. Not a bad run. But did he smuggle anti-HUAC messages into this gangster flick? The romantic in me likes to think so.

The two female leads are both good-looking actresses with truncated careers. Helena Carter was a Columbia University fashion model discovered by Universal Pictures who never liked the roles she got. She only made 13 movies between 1947 to 1953, including “Invaders from Mars,” her last. She lived a long life. Payton was a Minnesota/Texas, who made 12 features between 1949 and 1955, including “Bride of the Gorilla,” with Raymond Burr; but she had a temptuous off-screen life. She had a string of lovers (Howard Hughes, Bob Hope, George Raft), became engaged to Franchot Tone, a leading man 20 years her senior, then began cheating on him with Tom Neal, a former boxer and B-movie star (“Detour”). One night, on her front lawn, Neal beat up Tone, breaking his nose and jaw. She wound up marrying Tone but kept seeing Neal until the inevitable divorce. That scandal basically ruined her career. Alcoholism and drug addiction didn't help; she died in 1967 at age 39. A biography of her life, with this movie's title in it, “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye: The Barbara Payton Story,” was published in 2007.

She’s the only one who says that line in the movie, by the way. Right before she shoot Cotter, she tells him, “Kiss Tomorrow Goodbye.” The line isn’t in the book; it’s just the title.

SLIDESHOW

Sunday April 05, 2020

Movie Review: The West Point Story (1950)

WARNING: SPOILERS

James Cagney starred in only four musicals during his career, and it’s instructive comparing the first, “Footlight Parade” (1933), with the last, this one, “The West Point Story” (1950), 17 years later.

In both, Cagney is an impresario of musical numbers. He thinks them up and nurses them along. In both, the love interest is his straight-shooting blonde assistant (Joan Blondell, Virginia Mayo). Both are vehicles for up-and-coming Warner Bros. singing stars (Dick Powell/Ruby Keeler; Doris Day/Gordon MacRae). And in both, at the end, one of the leads can’t go on, so Cagney has to sing and dance the finale.

Those are the parallels. More interesting are the differences.

In “Footlight,” Cagney’s character is surrounded by scantily-clad chorus girls as the movie sells sex in the midst of the Depression. In “West Point,” Cagney’s character is surrounded by buttoned-up military men as the movie sells patriotism in the midst of the Cold War. The first movie is rat-a-tat-tat and scrambling; it’s gritty Warner Bros. The last is self-satisfied and cartoonish; it’s absurdly cheery and totally phony. You watch both and can’t help but wonder what happened to Warner Bros., the film industry, and us.

Many dilemmas

Elwin “Bix” Bixby (Cagney) is an exacting dancer/choreographer/director who’s making a go in a small club in New York. We see him hopping up and down angrily when his performers don’t do the routine just so. Then he shows them how. Then he leaves to place a bet on the horses. He’s got a gambling addiction. That’s the first dilemma.

His girl, the leggy Eve Dillon (Virginia Mayo), is going to leave him because of it; she says she got an offer to perform in Vegas. But then Bix gets a call from Harry Eberthart (Roland Winters), his corrupt ex-partner, who wants Bix to direct West Point’s annual musical, “100 Days Till June.” Why? It seems his nephew, Tom Fletcher (Gordon MacRae, five years before playing Curly in “Oklahoma”), is the star of the show. He’s a cadet who wants a military career but his uncle thinks he’s got a voice and wants him for Broadway. At first, Bix stands his ground. “I will not steal your nephew out of West Point,” he says in the Cagney manner. But then Eberhart mentions the Vegas offer for Eve—which he orchestrated—and Bix knows he’s trapped. He seals the deal not with a handshake but a sock to Eberhart’s jaw. It’s accompanied by comic sound effects. Eberhart rises, dazed, from behind his desk. All that’s missing are the animated birds circling his head.

That’s the second dilemma: Going to West Point to convince Tom to make a career out of singing.

Good news? Tom’s got a voice. Bad news? There are no women in the show, so the princess is played by the biggest of the bunch, Bull Gilbert (Alan Hale, Jr., 14 years before becoming the Skipper on “Gilligan’s Island”). Bix tries to show him how to do his dance number, Bull gives him a wolf’s whistle as a joke, and Bix cold-cocks him. Cue more comic sound effects.

For that, Bix is about to get booted from the Point before the job even begins. I guess that’s the third dilemma. The boys stick up for him but the commandant is wary. Bix’s own military record includes both absurd insubordination and absurd bravery. But a deal is struck. Bix can stay if he becomes a cadet himself.

That’s actually the germ of the idea that led to this movie being made in the first place. From John McCabe’s biography of Cagney:

[Cagney] recalled that his idol George M. Cohan, in preparing for a scene in one of his musicals, had inveigled West Point’s superintendent into allowing him to live as a cadet on the premises for a week.

So Bix gets a high-and-tight but remains the same short-tempered curmudgeon. Except now he wants to steal Tom for himself. In that regard, he gets in touch with his friend, movie star Jan Wilson (Doris Day, third-billed), whom he plucked from the chorus back in the day. She agrees to go to a military hop as Tom’s date. And it works! They fall for each other.

Except Eve finds out about Bix’s machinations and is ready to leave him again. Is this the fourth dilemma? Or is it when Bix loses the respect of the men because he lies about having a pass? This latter problem is solved when he admits to the lie and is forced to walk a punishment tour in the quad—filmed against a blue screen; the principles were never at West Point—but oddly it also solves the former problem. Tom explains to Eve what’s going on and Eve blows Bix a kiss and all is forgiven even though Bix is still trying to become Tom’s agent.

In fact, Tom and Jan get engaged! But instead of Tom agreeing to follow Eve to Hollywood, Eve follows Tom to West Point. So Bix finagles a way to get the studio to drop the hammer on her. That works, and Tom resigns his commission, but by now Bix doesn’t want to be Tom's agent, so … Blah blah blah. It’s like this, one dilemma after another, many of Bix’s own making, and it culminates with Bix convincing the French premier to pardon Tom by showing him the Medaille Militaire Bix was awarded in World War II. “This is our highest decoration!” the premier says, in case we haven’t figured it out.

So the West Point show goes on—with movie star Jan now playing the princess, and Bix replacing Hal (Gene Nelson, “Oklahoma”), whom he inadvertently coldcocks backstage. Tom and Jan wind up together (but pursuing separate careers?), Bix and Eve wind up together, and the boys present Bix with the book and libretto of the show so he can stage it on Broadway. The end. Mercifully.

Great guardians of human liberty

“West Point” was directed by Roy Del Ruth, who directed Cagney in four movies between 1931 and 1934: “Blonde Crazy,” “Taxi,” “Winner Take All” and “Lady Killer.” The first two aren’t bad, and even the bad ones are worth watching for Cagney. Not here. Cagney actually hurts more than helps. He overacts, particularly with the on-stage temper tantrums, and seems in danger of becoming a parody of himself: more Frank Gorshin than Rocky Sullivan.

MacRae is good, if a bit blank, while Day is saccharine enough to make your teeth hurt. Hale is fine. (Did Cagney act with other father-son combos? Hale Sr. appeared in several early ’40s Cagney flicks.) Mayo is fine, too, but she’s way too young for Cagney, who’s an old 51. He’s 17 years older than in “Footlight Parade,” and looks it, while she’s basically the same age as Blondell: 30 instead of 27.

The pre-code titillation of “Footlight” is sadly absent. Eve shows up at West Point in short shorts with legs up to here and not one cadet gives a second glance? Or a first? The camera in “Footlight” knows what it’s offering us as chorus girls change into their Busby Berkeley outfits, but this camera is as dumb as the cadets. It’s Sgt. Schultz: It knows nothing. Nothing.

But it knows everything about chest-beating patriotism. MacRae is forced to do a number called “The Corps,” which he mostly intones, as a military chorus hums and thrums behind him:

Duty. Honor. Country. This is why the dream materialized into the stone and steel and spirit that is West Point. A dream that can be measured by the names of its giants striding through the pages of American history. Giants whose voices rang so loud that the entire world trembled, yet who were once cadets, marching nervously across the plain. Cadets like Lee, Grant, Pershing; MacArthur, Wainwright, Arnold; Patton, Bradley, Eisenhower. And thousands of others, who left this point on the Hudson to end their earthly lives in the dirt and mud of foreign lands.

That’s laying it on a bit thick. But whatever. Depression, World War II, communist rise: Americans had been through a lot. So I guess … Oh, he’s not done?

Men who didn’t want wars and didn’t make wars but simply fought them because they had the understanding and the courage to want a free America.

“A free America”: That should be enough for HUAC, right? To show that Hollywood is patriotic and … What? More?

Because like Washington, Hamilton, Jefferson, they believed in a dream that is West Point. A legend, a tradition, one of the great guardians of human liberty.

“Guardians of human liberty”! There we go. That’s the trump card. And … nope:

Please, God, may we always keep faith with them, as they have with us. For duty, for honor, for country.

Can you imagine a culture so scared and cloistered that this passes for entertainment?

Cagney liked it anyway. Via McCabe:

“It’s one of my favorite pictures,” said Jim. “Cornball as all hell, but don’t let anyone tell me those songs by Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn aren’t worth listening to. They were sure worth dancing to.”

A year later, Del Ruth would direct a musical, “Starlift,” with a similar theme—military dude + Hollywood star—and with almost all the same actors: Day, MacRae, Mayo and Nelson. Just not Cagney. Or he was relegated to a cameo. As himself.

Watch “Footlight Parade” instead.

Cold War America: cheery, buttoned-up, sexless.

Monday May 14, 2018

Movie Review: Cet homme est dangereux (1953)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Cet homme est dangereux” is a French B-movie based on a British novel about an American tough guy. Expect dislocation.

Example: The movie opens on a closeup of an actor dressed as an American cop laying out in APB fashion how American gangster Lemmy Caution (Eddie Constantine) escaped from Oklahoma State Prison, and was “last seen heading east.”

Where is he in the next scene? Marseilles. So, yeah, “east.”

All of this is done both on the cheap (just a closeup) and intriguingly (great lighting). You can immediately sense the talent.

I first heard of “Cet homme” when it was praised by Betrand Tavernier in the documentary “My Journey Through French Cinema,” and it’s pretty good for what it is. It’s noirish, with nice, tough-guy snatches of dialogue. But it’s got a plot that’s tough to unpack.

I first heard of “Cet homme” when it was praised by Betrand Tavernier in the documentary “My Journey Through French Cinema,” and it’s pretty good for what it is. It’s noirish, with nice, tough-guy snatches of dialogue. But it’s got a plot that’s tough to unpack.

Avant Godard

First, the dialogue.

Early on, before we really know Lemmy, a woman on a boat tells him, “I’m sick,” and this is his response: “Don’t worry. You suffer because you’re alive.” Lemmy may be American, but he speaks the French ennui. Later, he even gets meta. He rescues a dim-bulb American heiress, Miranda Van Zelten (Claude Borelli), and as they drive along Marseille’s coast, she starts talking in English. “Speak French!” he admonishes. “People don’t get subtitles here.”

Another woman, Constance (Colette Deréal), pulls up at his hotel, pretends like they know each other, and invites him back to her place for a whiskey. He hesitates.

She: Are you afraid of me?

He (getting in): No. The whiskey.

Dialogue like that just makes me happy. It can sustain me through a week of my own ennui.

As for the tough-to-unpack plot? I’ll say right off that Lemmy isn’t a gangster but an undercover G-man. The target (from the get go?) is French mob boss named Siegella (Grégiure Aslan), who is apparently in the process of kidnapping the heiress, Miranda, when Lemmy shows up on the boat to rescue her. He also finds a dead man in a state room (another G man?) and it pisses him off. He’s so pissed off he kills one of the gangsters, Goyaz, in cold blood and throws him overboard. So not exactly Elliott Ness.

Not sure if there was an original plan involving the stateroom guy but the new plan is to become reluctant partners with Siegella in kidnapping Miranda. So he can get evidence? And put Siegella away? I guess. But he seems to have enough of it fairly early and just keeps going.

It’s really one of those “Nobody trusts anybody” movies. Siegella doesn’t trust Lemmy—not because he thinks he’s a fed but because he’s an uncontrollable element. Lemmy doesn’t trust the women buzzing around him—and shouldn’t. Constance works for Siegella, which we find out soon enough, as does Miranda’s secretary, Susanne (Véra Norman). Another woman, an angry blonde named Dora (Jacquelline Pierreux), turns out to be Goyaz’s lover seeking revenge. She suspects Lemmy but teams up with him, and winds up being killed by Siegella. She is who she says she is; as is Miranda.

At one point, after Siegella and Lemmy agree to work together, Siegella wakes to find both Miranda and Lemmy gone. Traitors! But Lemmy isn’t gone; he’s checking in on Miranda himself, finds her gone, and suspects Siegella. Good bit. Eventually he figures it out: Miranda just flew to Paris for a haute couture fashion show—as heiresses do.

Lemmy uses Miranda as bait but it backfires. He takes her to a country estate, run by Siegella, and lets her play cards while he pretends to succumb to whiskey. For all his smarts and running around: 1) Dora winds up dead, 2) Miranda winds up kidnapped, and 3) Lemmy winds up in a shoot-out with two of Siegella’s men.

In the real world, that would’ve been the end of it: Siegella no longer needs Lemmy, n’est-ce pas? Except all of a sudden Lemmy has a satchel full of Siegalla’s vital intel. It's just there to keep the dishes spinning. So Lemmy, backed by the cops, returns to rescue Miranda, but the cops lose him en route and he’s on his own. He’s caught, tied to a bed, and the room is set on fire. He escapes, of course. The final battle takes place in a country garage. While Lemmy and Siegella duke it out, Miranda and Constance take turns dousing each other with a firehose. Where are the rest of Siegella’s men? Who knows? Hardly matters. After Lemmy chokes the life out of Siegella, and after Constance is properly wetted down, the cops finally arrive and we get our end.

Apres le firehose

What sells the movie are the visuals. It’s directed by Jean Sacha, who edited under both Max Ophuls and Orson Welles but only directed six feature-length films; this is the third. The cinematographer is Marcel Weiss, who worked under Bresson and has 37 DP credits. This is his seventh.

They work well together:

“Cet homme” was the second Eddie Constantine/Lemmy Caution film. There would be nearly a dozen more, including the celebrated “Alphaville,” directed by Jean-Luc Godard in 1965. Constantine last portrayed him in 1991: “Germany Year Nine Zero,” also directed by Godard, which is described as “a post-modern film about Germany after the fall of the Berlin Wall.” So a long way from the firehoses.

Monday February 01, 2016

Movie Review: Big Jim McLain (1952)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Big Jim McLain” is a fascinating cultural artifact. It’s the first movie from John Wayne’s independent company (eventually: Batjac Productions), and it’s apparently the only Hollywood movie that turns members of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)—which was, at the time, ruining Hollywood lives—into heroes.

A little background before I get to the greater irony. HUAC’s original reason for investigating Hollywood was as follows: 1) The film industry was crawling with commies, who were 2) injecting red propaganda into mainstream American movies and warping American minds. But while HUAC had some examples of 1), it was never very good at proving 2). In 1947, for example, it called Ayn Rand, a member of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American Ideals (like Wayne), to testify, and she tagged the World War II-era “Song of Russia” as propaganda. The Russians in it, she said, were smiling, and Russians never smile. “Pretty much no,” she said when questioned. “If they do, it is privately and accidentally.”

As a result, during the second round of Hollywood hearings that began in 1951, HUAC pretty much dropped 2) and focused on 1). Basically: Betray your friends or end your career. Or both, in the case of Larry Parks.

Go get 'em.

Here’s the awful irony: While HUAC had trouble proving left-wing propaganda in Hollywood movies, preview audiences had no trouble at all distinguishing the right-wing kind in “Big Jim McLain.” Among the preview comments, as recounted in Scott Eyman’s biography, “John Wayne: The Life and Legend”:

- “Good in spots, except for the too, too obvious propaganda (and I am NOT a Commie).”

- “[Stephen Vincent] Benet would turn over in his grave the way he was quoted.”

- “One wonders about the future of this country when this sort of tripe passes for Americanism.”

The movie presents HUAC as surprisingly toothless. (All the better, I suppose, to show us the need for a stronger HUAC.) It opens with a left-wing professor taking the fifth before the committee while investigator McLain (Wayne) and his sidekick Mal Baxter (James Arness) seethe on the sidelines. Here’s Wayne’s voiceover:

Eleven frustrating months we rang doorbells and shoveled through a million pages of dull documents, and proved to any intelligent person that these people were communists, agents of the Kremlin; and they all walk out free.

Yes, that’s what happens. The witness is excused and Wayne claims that Dr. Carter will return to his “well-paid chair as a full professor of economics at the university—to contaminate more kids.” Instead of, you know, having his life completely upended. Or winding up in jail. (See: Hollywood Ten.)

Wayne’s voiceover, believe it or not, is actually the third voiceover in the film. And at the three-minute mark. That’s how disorganized this thing is.

The first voiceover (Harry Morgan) is the folksy, cornball kind. It talks up Daniel (or “Dan’l”) Webster, and suggests you can summon him from his grave by calling his name:

And sometimes the ground will shake and he’ll respond, “Neighbor, how stands the union?” And you’d better answer the union stands as she stood: oak-bottomed and copper-sheathed! One and indivisible! Or he’s liable to rear right out of the ground!

Then we get a bland, bureaucratic voice to talk up HUAC’s good works:

We, the citizens of the United States of America, owe these, our elected representatives, a great debt. Undaunted by the vicious campaign of slander launched against them as a whole and as individuals, they have staunchly continued their investigation, pursuing their stated beliefs: that anyone who continued to be a communist after 1945 is guilty of high treason.

Then we get the rest of this horseshit movie.

Vasquez! Cohen!

McLain and Baxter (who, like a lot of Wayne’s 1950s sidekicks, is a hothead, to better highlight Wayne’s cool one), fly to Hawaii to ferret out a Soviet cell there. The ringleader is named Sturak, and he’s played by Alan Napier, who would later play Alfred, Bruce Wayne’s butler, in the 1960s camp classic “Batman.”

What’s the commie plan? To “create a paralysis of island shipping and communications.” Who’s a commie? Eggheads mostly: a doctor, a labor lawyer, a bacteriologist, a rising star in the labor union. One guy, who looks like a bruiser but has a glass jaw when fighting McLain, claims to be a country club type, and condemns “white trash and niggers.” Back then, you see, commies played up our “Negro problem,” and this was Wayne’s way of showing that they, and not Strom Thurmond, were the true racists. Our open-mindedness, in fact, is on display in the end, when smiling soldiers report to duty as Wayne, and his fiancée, Nancy (Nancy Olson), stand at attention nearby. Here are the names:

- Shulman!

- Donahue! (black)

- Vasquez!

- Cohen!

- Pratt! (black)

- St. John! (Asian)

For a non-military movie, we get a lot of homages to the military. In Hawaii, McLain and Baxter first stop at the final resting place of the U.S.S. Arizona. The soldiers aboard, Wayne tells us, “have been there since Sunday ... Sunday, December 7, 1941.” The date that will live in infamy. And the one that propelled Wayne to join the military. Kidding. Wayne fought World War II from a Hollywood backlot. He became a star.

The plot is thin. McLain and Baxter hand out subpoenas, then get on the trail of Willie Namaka, a member of the party who’s been acting erratically, and who may be ready to talk. Early obvious clues as to commie headquarters (the Okole Maluna Club) are saved for the final reel. Nothing is smartly pursued except Nancy, by Big Jim, and she’s easily caught. You could argue that McLain, for a staunch capitalist, has a pretty lousy work ethic. Just as he and Baxter are on what seems to be a trail, his voiceover interrupts: “The weekdays were real dull. But not the weekends!” Then we get a travelogue of Hawaii: sailing, dinner and dancing.

Two extended comic relief sections go nowhere: a nutjob fellow traveler (Hans Conreid) claims to have met Stalin; and a brassy blonde (Veda Ann Borg) all but blackmails Big Jim into taking her out to dinner before handing over intel about Namaka. Everyone talks up Wayne’s size. He’s 6’4” we’re told numerous times; the blonde even calls him “76,” with its double meaning: inches and “spirit of.” That’s “a lot of man,” she adds. Arness, about the same size, and broader of shoulder, gets bupkis. No, that’s not true. He gets killed. Wayne fights on alone. Because that’s the Hollywood way.

Riding into the sunset

In the end, after McLain saves the day, we get a replay of the opening HUAC hearing in which the commies, including Sturak, plead the fifth and then walk away. Later, McLain has the following conversation with Honolulu’s Chief of Police Dan Liu, played with the expected stiffness by Honolulu’s Chief of Police Dan Liu:

Liu: I wonder how Mal would’ve felt about this fifth amendment.

McLain: He died for it. There are a lot of wonderful things written into our constitution that were meant for honest, decent citizens, and I resent the fact that it can be used and abused by the very people that want to destroy it.

“Big Jim McLain” is a low-budget affair, a B movie with an A actor; but its suggestion that HUAC was an upright but surprisingly toothless organization whose hands were tied once the suspect decided to plead the fifth, and that it, and not the accused, were the victims of “vicious slander,” is beyond insulting.

Nobody seems to get it. For most of its history, Hollywood movies have been unintended propaganda for the right. They’re neocon bedtime stories, tales of good vs. evil, in which good (generally white) triumphs over evil (generally not), and often with a gun. The whole thing is a century-long ad for the NRA. And at the height of Hollywood’s powers, when this absolutist, All-American message was being broadcast around the world, dominating the global film industry in a way that few American enterprises ever dominated their industries, HUAC attacked, and damaged, this Hollywood brand. It accused a successful capitalist enterprise of communist sympathies, and hurt its bottom line in the name of capitalism. Then it rode off into the sunset not knowing how stupid it was. But it left behind this movie to remind us.

UnAmericans this way.

Thursday August 13, 2015

Movie Review: How to Marry a Millionaire (1953)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Here’s how dumb I am: I kept waiting for the “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend” number. As the movie began (interminably, with an overture), I also wondered, “Wait, isn’t Jane Russell supposed to be in this?” Of course, I was thinking of “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” Marilyn Monroe’s other 1953 hit; but to my credit, “Diamonds” does fit better with this title.

And I did get “Diamonds are a Girl’s Best Friend”—just not as a song.

Halfway through the film, at a private fashion show, Pola (Monroe) is modeling a red swimsuit in front of Tom Brookman (Cameron Mitchell), a gas-pump-jockey-looking rich bastard who is really interested in Schatze Page (Lauren Bacall), and the woman hosting the show says, as Monroe poses, “You know, of course, that diamonds are a girl’s best friend.” Which has got to be one of the quickest pop-cultural-reference turnarounds in history. “Blondes” was released in August and “How to Marry a Millionaire” in November. Did the song get released first? Did screenwriter/producer Nunnally Johnson (“The Grapes of Wrath,” “The Dirty Dozen”) see an early clip and figure it would be an indelible cultural moment?

The movie is actually full of such sly winks. When Schatze is trying to convince aged Texas oil man J.D. Hanley (William Powell, the least-likely Texas oil man in movie history) that she likes older men, she references Bacall’s real-life husband: “Look at Roosevelt, look at Churchill, look at that old fella, what’s his name, in ‘The African Queen.’” Ditto Loco (Betty Grable), stuck in a picturesque Maine cabin and listening to big-band music on the radio.

The movie is actually full of such sly winks. When Schatze is trying to convince aged Texas oil man J.D. Hanley (William Powell, the least-likely Texas oil man in movie history) that she likes older men, she references Bacall’s real-life husband: “Look at Roosevelt, look at Churchill, look at that old fella, what’s his name, in ‘The African Queen.’” Ditto Loco (Betty Grable), stuck in a picturesque Maine cabin and listening to big-band music on the radio.

Loco: Good old Harry James.

Waldo: Is it? How can you tell?

Loco: How I can tell is because it is Harry James.

James was Grable’s husband. The punchline is that the bandleader they’re listening to is really Ziggy Colombo. Are these girls ever right? Oh, girls.

No means yes

They don’t come off well, do they? Set aside the gold-digging aspect for a moment. Loco mistakes the “lodge” comment of Waldo Brewster (Fred Clark) for an elk’s lodge rather than a romantic tryst, then mistakes forest ranger Eben’s “my trees” comment for vast wealth rather than enthusiastic job responsibility. Schatze, the one who dreams up the scheme of three fashion models subleasing a swanky Upper East Side apartment in order to scam rich husbands, can’t even see the rich man beneath Brookman’s lack of necktie. She thinks he’s a gas-pump jockey like her ex. She doesn’t even question what he’s doing as the sole audience at a private fashion show. She also keeps verbally resisting him (“As soon as I finish this, I never want to see you again”) even as she keeps giving in to him. She’s a “no means yes” girl. Fun times.

Monroe’s Pola, who’s the dingiest of the trio, comes off best by being sweetest. Schatze keeps selling furniture to pay the rent, and dissing Brookman while leading on Hanley; Loco carps the entire time she’s surrounded by beauty; but Pola is nice to everyone. She’s that classic Monroe character: oblivious to her stunning impact. She finally falls for the man who owns the apartment, Freddie Denmark (David Wayne), because he tells her she looks great wearing glasses. (She does.) She’s also the best actor of the three.

It really was Monroe’s moment, wasn't it? Grable, 37, the biggest pinup of World War II, was about to end—she would only make two more movies, then a bit of TV, then nothing—and Bacall, still only 29, never did anything as long-lasting as her work with Bogart in the 1940s. But Monroe, 27, second-billed, became white hot afterwards and never cooled down.

The Greeks have a word for it

The movie is mostly interesting as cultural artifact. You get New York in the early 1950s, America before rock ‘n’ roll and Brown v. Board of Education, and the movie industry doing everything to compete with television. “Millionaire” was the first movie filmed in Cinemascope (but released second, after “The Robe”), and it’s saturated in Technicolor. So it’s wide, colorful ... and flat. And not just the characters. The first act takes place almost completely in that Sutton Place apartment, so you sensed right away that it was based upon a play—specifically “The Greeks Have a World for It” by Zoë Atkins, which debuted in 1930 and was made into a 1932 movie starring Joan Blondell, Madge Evans and Ina Claire, where it was retitled “Three Broadway Girls” to avoid Atkins’ innuendo. It also became a syndicated TV series in the late 1950s, starring Lori Nelson, Merry Anders and a pre-“Jeannie” Barbara Eden.

Could you make the film today? Doubtful. You’d need a different spin. The girls couldn’t be such gold-diggers, not to mention dumb. Not to mention girls.

Thursday June 06, 2013

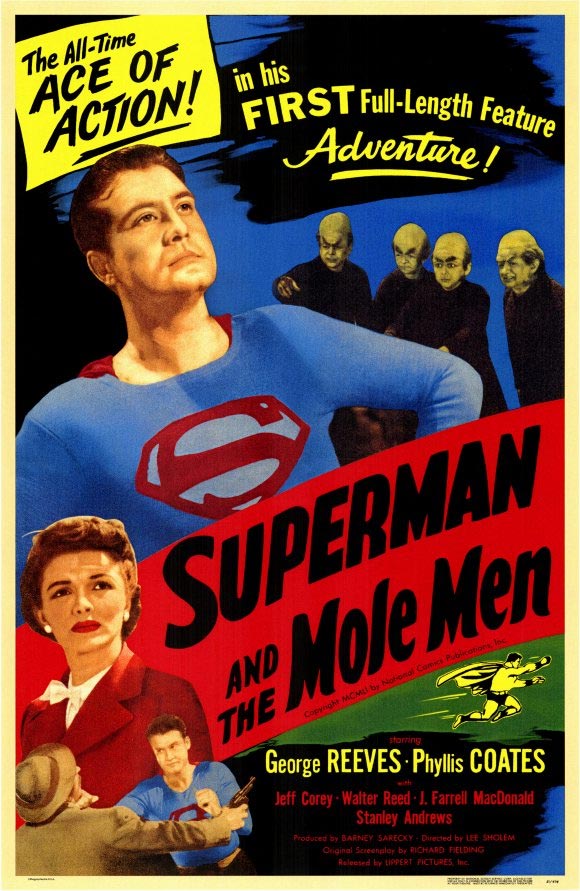

Movie Review: Superman and the Mole-Men (1951)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Superman and the Mole-Men” is less movie than intro to the 1950s TV series. It only last 60 minutes. It just seems to last as long as a movie.

At the same time, it’s an odd intro for the series. We’re never in Metropolis, never see the Daily Planet, never meet Perry White or Jimmy Olsen. It’s just Clark and Lois visiting the town of Silsby, Texas, population 1,430, to write about the deepest oil well ever drilled: six miles deep. As they arrive, though, the well is being shut down. Why? I would’ve guessed because they drilled six miles deep and never struck oil but apparently there’s a more sinister reason for the shutdown. Hideous things are emerging, mole men, who cause old men to have heart attacks and young women to scream, and who bring out the vigilante in the small-minded and intolerant. That’s what the movie’s really about. If the villains in the first two “Superman” serials were megalomaniacs bent on world domination (Spider Lady and Lex Luthor, respectively), the villains of “Superman and the Mole-Men” are your next-door neighbors, preaching intolerance and vigilante justice.

and intolerant. That’s what the movie’s really about. If the villains in the first two “Superman” serials were megalomaniacs bent on world domination (Spider Lady and Lex Luthor, respectively), the villains of “Superman and the Mole-Men” are your next-door neighbors, preaching intolerance and vigilante justice.

Preventing this, standing in the doorway of injustice, as it were—in a move which prefigures other doorway stands (see: Atticus Finch)—is the Man of Steel, Superman, who, as the opening intro tells us, is “a valiant defender of truth, justice and the American way.”

Interesting sidenote. For most of his career, Superman had fought for truth and justice. Full stop. So why add “the American way” here? I’d always assumed a Cold War scenario, the American way vs. the Russian way, but according to Glen Weldon in his book, “Superman: An Unauthorized Biography,” it was a defensive salvo against another kind of intolerance. By this point, comic books and superheroes were seen as gateway drugs to juvenile delinquency and homosexuality. Public bonfires were even held in Southern cities to burn Action Comics, Detective Comics, Captain America, etc. Think of all of that money going up in smoke. Anyway, that's why Superman fights for the American way here. It’s patriotism as the last refuge of the witch-hunted.

Superman vs. the Second Amendment

The theme of small-town intolerance is particularly fascinating, since, in this movie, Superman himself is rather intolerant. If Kirk Alyn played Superman with wide-eyed bombast, amazed at the amazing things he can do, Reeves takes it down a notch. Or two. Or 10. Growing up in the mid-1970s, Reeves’ was considered the touchstone performance, the one and true Superman (until Christopher Reeve came along), but I was never a fan, and I’m even less of a fan now. Reeves’ indifference to the role permeates the character. His Clark Kent is strong and smug, his Superman vaguely disgusted and contempuous. (Maybe that is the American way.)

This is never truer than in the movie’s key scene.

Two Mole Men—midgets with low-budget furry costumes and bald wigs—have emerged from the well to creep around the small town of Silsby. To what end? I guess they’re just exploring. But they cause a heart attack and a scream, and they’re trailing radium, so rabble-rouser Luke Benson (veteran character actor Jeff Corey, doing good work) gathers a mob to capture them and string ‘em up. One is shot atop a bridge, but Superman, or at least a shitty animated version of Superman, catches him and carries him to the hospital, then seems to forget all about the other one, who is pursued by bloodhounds into a shack. The shack is lit on fire. What to do? He worries for a bit, then crawls to safety. I’m sure someone wanted him to dig to safety—mole man: hello?—but probably no budget for this. So he crawls.

Back in town, Benson and the mob hear that the first mole man didn’t die after all, some nut in a cape saved him, so Benson incites the mob with a speech that sounds straight out of the Sarah Palin/Tea Party cannon:

Now them two reporters from back east … they’ll try to stop us, like as not, but we ain’t gonna be stopped. This is our town. We don’t need any strangers telling us what to do.

And off they go to lynch the little guy. Who’s there to stand in their way? Not Atticus Finch reading a book but Superman. It’s right through might.

The mob doesn’t know who they’re dealing with yet.

Mob guy: We’re running this town. Maybe we want to string you up, too!

Mob: Yeah!

Superman: I’m going to give you one last chance to stop acting like Nazi stormtroopers!

They blow that chance. A gun goes off and Superman has to shield Lois Lane (Phyllis Coates) from the bullet; then he urges her inside and away from the door, and says the following to the mob:

Whoever fired that shot nearly hit Miss Lane. Obviously none of you can be trusted with guns. So I’m going to take them away from you.

Which he does. He beats up a bunch of Texans and takes the guns from their cold, not-so-dead hands. How great is that? From the perspective of 21st-century political debates, in which nutjobs everywhere worry that Pres. Obama is “coming for their guns,” this is a laugh-out-loud moment. What used to be entertainment is now a nightmare scenario for the paranoid. Who knows? Maybe Superman put the fear in them in the first place.

Defender of truth, justice and sensible gun control laws.

Superman vs. the First Amendment

That's how this Superman deals with the Second Amendment. He's not much better with the First Amendment.

When the presence of the Mole Men becomes known, Lois tries to get to a phone to call in the story, but Superman urges against it.

Lois: I’m a newspaperwoman and I have an obligation to report the facts.

Superman: That’s true. But these facts would start a nationwide wave of hysteria. You saw what happened here tonight. No. If we’re going to stop this thing, it has to be stoppped here and now.

PR dude: He’s right, Miss Lane.

Lois (deflated): I guess so.

Oh, Lois. Where’s our feisty girl from the Fleischer cartoons or the Kirk Alyn serials? Or the comic book or comic strip? This is part of the tamping down of Lois Lane. She can’t hear the scoop for the wedding bells in her head. She promises to love, honor and obey even though there ain’t no ring on that finger.

So what happens after Superman dispenses with Luke and the mob? The escaped mole man returns with two others and a big ray gun, which they train on Luke, who screams in pain until Superman steps between him and the gun.

Luke: You saved my life.

Superman: That’s more than you deserve.

Eventually the mole men return underground and blow up the well. “It’s almost as if they were saying, ‘You live your life and we’ll live ours,’” Lois says, amazed. Superman nods.

And that’s the end.

“Superman and the Mole Men” is a dry, little black-and-white movie filmed in a dry, little backlot somewhere. Its main action consists of a midget in bald wig and furry suit being pursued over nondescript brush and hills. The whole thing makes me vaguely nauseous. It’s like something you’d only watch when you were sick in bed; and it would only make you sicker.

But it’s worth it for the gun scene.

Ferocious mole man cornered. Was Stan Lee thinking of this guy when he started writing FF #1?

Wednesday June 05, 2013

Movie Review: Atom Man vs. Superman (1950)

WARNING: SPOILERS

At some point I began to feel less antipathy toward, and more sympathy for, the people who made “Atom Man vs. Superman.”

Tough gig. With a miniscule budget and B actors and little time, you have to create a 15-chapter story about a super-powered being, Superman (Kirk Alyn), battling an evil scientist, Lex Luthor (Lyle Talbot), where, at the end of each chapter, the hero, or the hero’s friends, are in grave danger. You have to figure out the trap and you have to figure a way out of the trap that—most important—maintains the status quo. Everything has to stay the same but there has to be tension, conflict, and peril throughout. The rhythm of the series is thus: clash, separate, regroup; clash, separate, regroup. Until the final chapter when the hero captures the villain and we get to see the loveliest of words onscreen: The End.

How do you do this? How do you offer constant conflict and resolution while maintaining the status quo?

You make your characters pretty dumb.

The dumbest character

The characters in “Atom Man vs. Superman” are pretty dumb. No thug of Luthor can ever shoot Jimmy Olsen or Lois Lane. They have to leave them unconscious in a van that gets blown up or in a warehouse filling with gas or in a barn filling with exhaust.

They have to leave them unconscious in a van that gets blown up or in a warehouse filling with gas or in a barn filling with exhaust.

Superman, meanwhile, can use his amazing powers to get out of predicaments but never to capture anyone important. At the end of Chapter 4, for example, “Superman Meets Atom Man!,” Superman is forced into “the Main Arc,” which teleports its occupants into “the Empy Doom,” a kind of proto-Negative Zone, where one’s “lost atoms will roam forever.” At the same time, Lois is placed unconscious in a car hurtling toward a cliff. How will she be saved? By Superman, of course! But, wait, wasn’t he transported into the Empty Doom? A little too pleased with himself, Superman explains:

His machine didn’t affect me! My atomic structure is different than that of human beings. … I just moved so rapidly I became invisible to the naked eye!

Every kid in the audience: “So why didn’t you just grab Atom Man while you were at it? Or why don’t you go back to his hideout now? You know where it is, dude. You just left it.”

Instead, he gets in the car and drives Lois back. You read that right. Plus he forgets all about the hideout. Until he needs to find it again. But he can’t find it because it’s lead-lined. Which would seem to be a giveaway even if he hadn’t been there before.

Lex Luthor? Brilliant scientist, etc. Here, he actually invents the transporter beam 16 years before “Star Trek.” “This apparatus,” he says, “can accomplish the transmission of matter over short distances. Its secret ray breaks down the component atoms and reassembles them here.” He’s got ray guns that start fires and cause earthquakes, and he’s got the main arc, and he’s got a spaceship, a fucking spaceship in 19-fucking-50; and yet after he’s successfully transported Superman into the Empty Doom, and Superman’s image appears on TV, he buys into the scam that the image is live rather than taped, and he sends a lacky into the Empty Doom to make sure Superman is still there. Guess what? He is! And Superman uses the open channel to return to return to Earth! D’oh!

Even so, there’s no contest about who the dumbest character in “Atom Man vs. Superman” is. Perry White (Pierre Watkin) gets everything wrong:

- When Luthor demands money or he’ll destroy Metropolis River Bridge, Perry is sure nothing will happen.

- When Jimmy reports on one of Luthor’s men disappearing into thin air, Perry complains, “You can’t even cover a routine fire without getting hallucinations. … It’s a plain case of hysteria or hypnotism!”

- When Lois tells Perry about Superman’s secret messages from the Empty Doom, Perry says, “You were probably hypnotized!”

- When Jimmy himself is transported to Luther’s hideout, and even has the coin with which they did it, Perry refuses to print the first-person account, saying they can’t print it if they can’t prove it. But when Clark Kent disappears along with Superman, and both Perry and Lois wonder if they were the same man, Perry tells her to write that story. “If I don’t publish the story someone else will!” he says.

- When Luthor hires men to frame them and divert attention from himself, and Clark suggests as such, Perry says, “Sounds like the plot of a cheap detective story!”

- When Clark suggests that there’s a connection between Luthor and the villainous Atom Man, Perry responds, “Luthor is running a legitimate television station. I’m sure he’s on the level!”

Great Caesar’s Ghost, dude.

Does Perry White get anything right in this series?

The frightful, pointless Atom Man

According to Glen Weldon in his book “Superman: The Unauthorized Biography,” the movie is actually based on a storyline from the Superman radio series. What’s the story? I guess Luthor wants money and power, and I guess Superman does what he can to foil him, and I guess the Planet reporters are after a scoop.

In many ways “Atom Man vs. Superman” feels cheaper than the previous Kirk Alyn serial, “Superman” (1948). We get more stock footage (floods, fires). We get redos from the first serial: Clark Kent ducking behind a file cabinet and emerging, a second later, with a dancer’s lightness and a triumphant blast of music, as Superman. An entire episode is devoted to Lex Luthor telling his assistant, Carl (Rusty Wescoatt, who also played a henchman in “Batman and Robin”), the story of Superman’s origins on Krypton, which lets the producers re-use that footage.

Sure, for the first time, we get close-up shots of Kirk Alyn as Superman flying, steadying his arms, looking down with concern; but when he flies Superman is still mostly a cartoon. As is the flying saucer. That’s right. Luthor also has a flying saucer. Forgot to mention that. He winds up shooting it at the Daily Planet airplane to blow it up. You’d think flying saucers grew on trees.

Luthor has a secret identity in this one, too: the titular Atom Man, a frightful being in a … Naw. He’s just wearing a mask that looks like a totem-pole head. It looks like they took a jug, cut in eyeholes and a mouthhole, sprinkled on glitter, and plunked it on Lyle Talbot’s poor head. You know the scene in “Duck Soup” where Groucho gets his head stuck in a pitcher and Harpo draws a Groucho face on it? Like that.

So what’s the point of Atom Man? Why ever be Atom Man when you’re Lex Luthor? I’m not sure. Maybe they needed the character for the title. Maybe the atom bomb was all the rage in 1950, the year after the Soviet Union detonated theirs, and that’s why exploding atom bombs dominate the opening credit sequence. Was this the first use of A-bombs as entertainment? Is this how we reduce what’s fearful to us? By letting Hollywood producers have a go?

Atom Man is also necessary because, for much of the serial, Luthor pretends to go straight. He’s caught in Chapter 1 and paroled in Chapter 3, where, outside the prison, he tells the waiting press, “I’ve invested in a television studio. My inventive genius will revolutionize the business!” He then uses the TV truck as a means of spying on the city. He even hires Lois Lane as a woman-on-the-street reporter, asking passersby questions such as, “Is city life more exciting than country life?” I.e., revolutionizing the business.

Luthor’s investment, by the way, makes total sense given the genre and the year. “Atom Man” was the 43rd Columbia serial. They would make 57 of them, the last in 1956. What killed the serial star? TV, of course. Superman may fight Luthor here but the serial’s producers knew who the real enemy was.

For some reason, Lex Luthor (top) turns himself into the jug-headed Atom Man (middle). Superman (bottom) can't figure it out, either.

Is that a missile between your legs or are you just happy to see me?

Other changes? Noel Neill’s Lois is less of a grump. She smiles so much, particularly when Superman is around, that my cheeks hurt just watching. Jimmy (Tommy Bond) is the same, Perry is dumber. Alyn’s Clark feels subtler this time around—he plays the nerd and the coward more often—but his Superman is a bit stiffer, his voice more stentorian. He says everything with an exlamation point! Like a comic book character!

For all its cheapness and stupidity, though, “Atom Man vs. Superman” presages many things in the Superman cinematic ouevre:

- The shot of the dam breaking and about to flood the town is a forerunner to the Hoover dam sequence in “Superman” (1978).

- Lois draws glasses on a picture of Superman to see if he’s Clark Kent, as in the opening to the Donner cut of “Superman II.”

- Lex Luthor creates synthetic kryptonite here; Gus Gorman (Richard Pryor) does it in “Superman III.”

- Superman gets trapped in The Empty Doom (or Phantom Zone) here, as does Supergirl in 1984’s “Supergirl.”

Even this headline, from when Supes fights his way back from the Empty Doom, presages things to come:

The serial also presages the ending of one of the darkest comedies ever made: Stanley Kubrick’s “Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” We all know that ending even if we haven’t seen the movie: Maj. ‘King’ Kong (Slim Pickens) riding the a-bomb out of the bay-doors of the plane and into the Russian night, wa-hooing it up, Texas-style, as the world moves inexorably toward its doom.

Here, Lex Luthor shoots a nuclear missile at Metropolis. Instead of forcing it into space, a la Chris Reeve in “Superman” (or “Superman II,” or “Superman IV”), Alyn rides it out to sea, where it explodes harmlessly. Or “harmlessly.” It is a nuke, after all:

What to make of a man with a nuclear-powered missile between his legs? This looks like a job for Freud.

Friday April 12, 2013

Movie Review: The Jackie Robinson Story (1950)

“The Jackie Robinson Story”is a cheap production filled with movie clichés. The young black boy who happens upon an error-prone group of white kids playing ball; he demonstrates what he can do bare-handed, and, as a reward, the white coach gives him a beat-up old glove. This glove follows him through his life. His brother comments upon it: “You always have that glove with you, Jackie.” Baseball is presented as Jackie's favorite sport, when, in reality, among the college sports he played, it was probably his least-favorite. Jackie himself, played by Jackie himself, is presented as dutiful son to a mammy-type (Louise Beavers), sexless suitor to a pretty, light-skinned girl (Ruby Dee), and almost without personality on the ballfield.

At only one point do you get the idea of the volcano simmering beneath the polite facade: When Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey (Minor Watson) gets in Jackie's face about what kind of abuse he'll face in the Majors; the abuse he'll have to take in order to make it in the Majors. The rest of the film is dreary, long-distance baseball shots, and heavy-handed back-patting pronouncements about equal opportunity. “The Jackie Robinson Story” is supposed to enlighten us and it does. It makes us realize how far we've come by showing us the inanities that passed for racial enlightenment in 1950.

-- November 22, 1995

Wednesday September 05, 2012

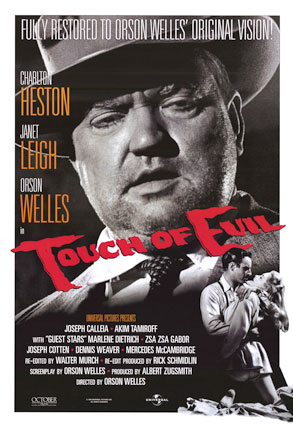

Movie Review: Touch of Evil (1958)

WARNING: TOUCH OF SPOILERS

Who do we like in Orson Welles’ “Touch of Evil”?

Yeah, I know. It’s such an amateur question to ask of such an auteur filmmaker. But it’s not a bad way to begin a discussion of the film.

Normally we like the protagonist. Normally he’s handsome and brave and the object of our wish-fulfillment. Here, Mexican cop Mike Vargas is, yes, handsome and brave, but, no, he’s not the object of our wish-fulfillment. For one, he’s played by Charlton Heston and that’s a sore point for cineastes 50 years on. “Touch of Evil” only got made the way it got made because Heston insisted upon Welles as director, so we should be grateful. We’re not. Because it’s still Heston: wearing dark make-up and a thin moustache and annunciating lines as if they were chiseled in marble.

Normally we like the protagonist. Normally he’s handsome and brave and the object of our wish-fulfillment. Here, Mexican cop Mike Vargas is, yes, handsome and brave, but, no, he’s not the object of our wish-fulfillment. For one, he’s played by Charlton Heston and that’s a sore point for cineastes 50 years on. “Touch of Evil” only got made the way it got made because Heston insisted upon Welles as director, so we should be grateful. We’re not. Because it’s still Heston: wearing dark make-up and a thin moustache and annunciating lines as if they were chiseled in marble.

Even so, shouldn’t we at least like Mike Vargas? Isn’t he the moral exemplar of the film? Isn’t he so upstanding, so dedicated, that he delays his honeymoon to tag along on a criminal investigation to make sure no innocent is railroaded by corrupt cop Hank Quinlan (Welles)? And doesn’t he get Quinlan in the end? And isn’t that admirable?

No. Here’s why.

What’s the matter with Vargas: Betraying Susie

“Touch of Evil,” follows two storylines: Quinlan’s investigation into the death of Linnekar, whose car is blown up at the Mexican border; and the stalking and eventual assault on Vargas’ American wife, Susie (Janet Leigh), by the Grandis, who are after Vargas because he put one of their own behind bars. Vargas immediately recognizes the first danger but never the second. Fearing for Susie’s safety, he pushes her away ... and into the arms of men who do her harm.

Let’s cut to a scene halfway through the movie. By this point, Quinlan and his toadies are grilling their No. 1 suspect, Sanchez (Victor Millan), in his apartment, and Vargas goes across the street to make a phone call. The proprietor of the store is a woman, blind, with a sign that reads “If you are mean enough to steal from the blind, help yourself.” When Vargas finally gets through to Susie at the Mirador Motel, they have the following conversation:

Vargas: Darling, the news is bad. Quinlan is about to arrest that boy Sanchez,

Susie: Oh Mike, is that why you called—to tell me somebody’s been arrested?

Vargas: No, that’s not really why I called. (Turns away, whispers) It’s to tell you how sorry I am about all this. And how very much I love you.

[Pause]

Vargas: Susie?

Susie: I’m still here my own darling Miguel.

Vargas: Oh, I thought you’d fallen asleep.

Susie: I was just listening to you breathe.

This latter part of the conversation could be any couple on their honeymoon. But they’re not on their honeymoon. The wife is ready:

But this is who Vargas is spending his honeymoon with:

The woman is as blind as justice, which is what Vargas is pursuing; but Welles also makes her ugly, which is the kind of justice Vargas will find. The discrepancy between the two women—the one Vargas should be with and the one he chooses to be with—is so great that, watching the movie a second time, I burst out laughing. Vargas doesn’t seem admirable here for keeping an eye on Quinlan and ignoring his wife. He seems a fool.

Then it gets worse. After Susie is terrorized, kidnapped, and possibly gang-raped by the Grandi gang, Vargas finally shows up at the Mirador Motel. The place is empty except for the night manager (Dennis Weaver, overacting). Presented with overwhelming evidence, Vargas remains uncomprehending. These are among the things he says:

- “The lights seem to be out in all the cabins.”

- “Party? What party?”

- “Brawl? You mean there was some kind of a fight?”

- “This can’t be my wife’s room.”

He’s not even concerned about Susie until he finds the briefcase with his gun missing. That’s what really sets him off: Not the missing wife but the missing, Freudian gun. Only then does he react.

Or overreact. He goes on a rampage, careering around on the Mexican side of the border and tearing up bars, in search of Susie. He basically goes from being a blissful idiot—thinking the world is all chocolate sodas—to being a malicious idiot. At one point, when a helpless Susie waves at him from a nearby balcony, he’s too busy looking for her to find her. In the end, she winds up in prison, charged with Quinlan’s murder of Uncle Joe Grandi (Akim Tamiroff). When he visits her, she says what she’s said to him throughout the movie: “Don’t go!” So what does he do? He goes. In pursuit of justice, which is blind and ugly.

As bad as all that is, he’s even worse in the final act.

What’s the matter with Vargas, part II: Betraying Menzies

At the prison, he convinces Quinlan’s best friend, Sgt. Pete Menzies (Joseph Calleia), to wear a wire to entrap Quinlan for the greater good. But as Menzies is doing this, betraying his best friend for the greater good, Vargas, skulking around and under a bridge, gets too close with the receiver, and Quinlan, hearing echoes of his own conversation, realizes he’s being recorded and betrayed. So he shoots Menzies with Vargas’ gun. It’s a great image: When Menzies goes down, the man figuratively behind him, Vargas, is literally revealed. This shooting sets up another great image: Quinlan stumbling down the riverbank to wash his blood-soaked hand in the river, which is also filthy. Nothing comes clean in Welles’ world.

At this point, Vargas has several options. While Quinlan is occupied with his hand-washing, he could, 1) take his gun back; 2) knock out Quinlan; 3) grab his transmitter/recorder and run away. But what does he do?

Earlier in the movie he had needlessly lectured Menzies in the Hall of Records. “What about all the people put in the deathhouse?” he asks in that marble-shitting voice of his. “Save your tears for them.” Now he needlessly lectures Quinlan. Doing so, he wakes a sleeping giant:

Vargas: Well, Captain. I’m afraid this is finally something you can’t talk your way out of.

Quinlan: You want to bet? [Pauses] You killed him, Vargas.

Vargas: C’mon, give me my gun back.

That’s actually funny. In a second, Vargas goes from sounding like an arresting officer to sounding like the smallest kid on the playground. C’mon, give it back. It’s up to Menzies, with his dying breath, to kill Quinlan for him.

Just think of what Menzies has done here. He betrays his best friend for the greater good. Then he gets shot by his best friend because Vargas screws up with the transmitter. Then after Vargas screws up yet again, allowing Quinlan to get the bead on him, Menzies shoots and kills Quinlan before dying himself. Now that’s a man who deserves a good eulogy. But when assistant D.A. Al Schwartz (Mort Mills) arrives with Susie, this is the eulogy Vargas gives him:

That’s Menzies. He’s dead.

At which point he rushes to his wife. It’s the one time in the movie he rushes to his wife and it’s the one time he shouldn’t.

But there’s more. Consider it the movie’s gloriously cynical punchline.

Throughout, Vargas has basically jumped storylines to pursue a greater good. He’s trying to prevent Quinlan from using his so-called intuition as a means to railroad another innocent—Sanchez—with false evidence. But in the end, in a by-the-way manner, Schwartz informs us that Sanchez actually confessed to the crime. He did kill Linnekar.

Quinlan’s famous intuition—which beats Vargas’ intuition, which suggested going after poor Eddie Farnham (Gus Schilling)—was right again.

By jumping storylines, Vargas creates tragedy out of both storylines. If he’d stayed with Susie, she wouldn’t have been terrorized and assaulted. And if he hadn’t tagged after Quinlan, Quinlan wouldn’t have died, Menzies wouldn’t have died, and the right man, Sanchez, would have been railroaded for the right crime.

Vargas isn’t the hero of “Touch of Evil.” He’s what causes everything to go so horribly wrong.

“You killed him, Vargas.”

What’s the matter with Quinlan: Murder and railroads

So who do we like in this movie then? Vargas’ opposite? Quinlan?

Welles certainly has a habit of playing likeable scoundrels: Kane, Harry Lime, Falstaff. Some are more charming in their rise (Kane), some more sympathetic in their fall (Falstaff), but all are usually smarter than the characters around them.

As here. Quinlan’s introduction reminds me of one of the most famous introductions in movie history: Rick Blaine (Humphrey Bogart) in “Casablanca.” First we hear everyone talking about him; then we’re allowed to see him. Rick Blaine, though, is obviously a hero: resplendent in tux, smoking a cigarette, exuding cool. Quinlan, in contrast, is repulsive: chomping a cigar, swaddled with extra weight, barely able to lift his girth from an automobile.