Thursday March 14, 2024

Movie Review: Oppenheimer (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Did anyone tell Christopher Nolan, as politely as possible, “Hey Chris, you might want to take a breath”? Probably not. Breathless is Nolan’s default.

Last summer my twentysomething nephews asked me which of the Barbenheimer films I liked best, and for a moment I pondered the joys and issues of both films before side-stepping toward what felt like the truer response: “I’m happier that ‘Oppenheimer’ was made.” It’s a movie for adults about some of the most serious topics of the 20th century: the creation of the Atomic bomb and McCarthyism. And it was done hugely and beautifully and released in the summer. My god, the summer! What a joy that is. How much we should be kissing Nolan’s ring for giving us a big, serious film in July.

And yes, you could say “Barbie” was a movie for adults about important topics. But it’s several times a fantasy whose interest in the end is about power and partying. “Oppenheimer” is about power and intellect. It luxuriates in smarts. It’s an ode to genius.

Chain reactions

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

- The main one: the journey of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) from studying quantum physics in Europe to leading the Manhattan Project and beyond

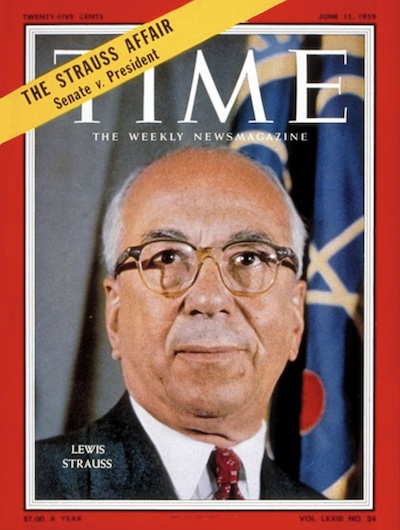

- His interrogation in a 1954 closed-door congressional session, masterminded by Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), that leads to his dismissal from government service

- Strauss’ interrogation before Congress in 1959, when his appointment as Sec. of Commerce is rejected

Live by the congressional hearing, die by the congressional hearing. That old saw.

Are there too many “gotcha” moments? Too many “reveals”? Oh, so Strauss isn’t a good guy? He’s the main villain? And David Hill, tossed up as a potential enemy, and whose clipboard Oppenheimer sends clattering across a train station floor, and, lest we forget, is played by Rami Malek, he stands up for him? And oh no, Oppie’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), is going to testify, but she drinks too much, and now she’s hemming and hawing and looking down at her lap and maybe itching to get the flask out of her purse as the prosecutor digs in. But wait! She totally turns things around! She makes him look bad and gets the congressmen on Oppenheimer’s side! Yay!

I also don’t get Alden Ehrenreich’s role. He’s supposed to advise Strauss during his congressional hearing but turns against him, or at least roots against him, when he finds out what a jerk he is. I guess he’s just there to signal what we’re supposed to feel. “Chris, what’s my motivation in this scene?” “You don’t have a motivation. You don’t even have a name.”

With all this carping, you’d think I didn’t like the movie. I did. It opened up (as much as anything could) the world of early 20th century quantum physics for me. And it was fun seeing characters excited to see Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh). Hell, it was fun seeing someone portraying Niels Bohr. Or Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), Richard Feynman (Jack Quaid) or Edward Teller (Benny Safdie). And those are just the names I know. Imagine you’re a scientist watching this. It would be like me and “42”: Hey, Clyde Sukeforth! Cool!

So I liked all that and the early amazement at Oppenheimer’s intellect: learning Dutch in six weeks, knowing Sanskrit, reading Proust and Eliot and quoting Donne. And I just loved David Krumholz’s Isidor Rabi, the fellow Jewish-American physicist who humorously chastises Oppenheimer for learning Dutch while not knowing basic Yiddish, then feeds him like a Jewish mother. That’s a supporting role I could’ve seen expanded. I smiled every moment he was on screen. (Rabi’s relatives, apparently, felt otherwise.)

And when Matt Damon’s Col. Groves shows up? So fun. The “We need to get this done by any means necessary so get out of my fucking way” attitude, but with a glimmer in the eye.

Does the movie lose itself about 90 minutes in or did I just get tired? More, does the tripart structure (the trinity structure?) take away from the magnitude of the discovery—the moment when we realized that all that intellect and progress was just leading us toward global destruction? These are its last lines, a flashback to Princeton 1946:

Oppenheimer: When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world …

Einstein: I remember it well. What of it?

Oppenheimer: I believe we did.

Then he stares into the void and feels the horror of the accomplishment. Some have criticized Murphy’s performance as too wide-eyed and one-note, and, given everything Oppie did, he does feel passive. But Cillian is amazing for staring into the void and feeling the horror. (Cast him as Col. Kurtz.) But should that moment have been at Princeton 1946? Is there a reason it’s Princeton 1946?

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The Strauss affair was a huge story at the time, written about constantly, not to mention historically important: the only cabinet nominee between 1925 (Charles B. Warren) and 1989 (John Tower) to be rejected. What I find fascinating? I’d never heard of it. I was born in 1963, sure, but I read a lot of history, and a lot about that period, and … nothing. Even in Robert Caro’s thousand-page tome, “Lyndon Baines Johnson: Master of the Senate,” it’s mentioned only once, and off-handedly, not to mention parenthetically. In the lead-up to 1960, LBJ had to placate both right-wingers “and the great Senate bulls (he paid off a lot of debts to Clinton Anderson by cooperating in Anderson’s efforts to defeat President Eisenhower’s nomination of Lewis Strauss to be Secretary of Commerce…”).

Should that have been the lesson of the film? If your power stays in the shadows, your legacy might, too? Or is that too “Amadeus”? Oppenheimer’s name continues to resonate while Strauss’ winds up in the dustbin. “Do you know nothing of my music?” It might’ve helped if Strauss had made music.

Teller’s hand

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

Kitty says this (repeatedly?) during the ’54 hearings, but it seems an odd question since Oppenheimer is never portrayed as a fighter. He’s a scientist who somehow falls into the Manhattan Project gig. (The film assumes he’ll get it—because he does—but I’m curious who else Gen. Groves considered, and why, in the end, he went with Oppenheimer.) Oppie’s a man with an open mind who listens to everyone around him and tries to keep the group together. Teller wants to work on his H-bomb theories? Sure. Have at. He’s a diplomat.

But since the film raises the question, what’s the answer? The obvious one is he feels the need to pay for his sins: A-bomb, Hiroshima, bringing us into the nuclear age, destroying the entire world.

I’m curious why he didn’t make more of the thin window between the end of the war in Europe (early May 1945, when our need for the A-bomb kind of ended) and the Trinity test (July). Was there too much momentum? I get the political calculus: You save countless U.S. GI lives and send a warning to the Soviets. But what was Oppenheimer’s calculus? To just see it through? Was it a bit of Stockholm Syndrome? He’d drunk the military Kool-Aid? Or did he, the perennial theorist, just want to see if it would work? Because if he’d wanted, he could’ve put the kibosh on it pretty quickly. Just resurrect the whole “Yeah, we might set the entire atmosphere on fire” scenario. “What are the odds of that?” “Oh, less than 10%.”

The most famous line Nolan has ever written, or filmed, is probably from “The Dark Knight”: You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain. Back in 2008, that felt like bullshit to me—in the film it comes out of nowhere—but, man, the times have proven it true. “Oppenheimer” adds an addendum: resurrection. For a time, J. Robert is the hero. But he lives long enough, and through reactionary times, to become the villain. Then the times shift again, his enemies are smited, and in the 1960s his wife stares daggers at Edward Teller’s proffered hand.

I suppose I should finish the book—it might answer some of my questions. I got 200 pages in last summer but got distracted. Either way, I’ll always have a fondness for the film. It’s the last movie I ever saw with my brother.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)