Movie Reviews - 2023 posts

Thursday March 14, 2024

Movie Review: Oppenheimer (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Did anyone tell Christopher Nolan, as politely as possible, “Hey Chris, you might want to take a breath”? Probably not. Breathless is Nolan’s default.

Last summer my twentysomething nephews asked me which of the Barbenheimer films I liked best, and for a moment I pondered the joys and issues of both films before side-stepping toward what felt like the truer response: “I’m happier that ‘Oppenheimer’ was made.” It’s a movie for adults about some of the most serious topics of the 20th century: the creation of the Atomic bomb and McCarthyism. And it was done hugely and beautifully and released in the summer. My god, the summer! What a joy that is. How much we should be kissing Nolan’s ring for giving us a big, serious film in July.

And yes, you could say “Barbie” was a movie for adults about important topics. But it’s several times a fantasy whose interest in the end is about power and partying. “Oppenheimer” is about power and intellect. It luxuriates in smarts. It’s an ode to genius.

Chain reactions

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

“Oppenheimer” has three intercut storylines:

- The main one: the journey of J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) from studying quantum physics in Europe to leading the Manhattan Project and beyond

- His interrogation in a 1954 closed-door congressional session, masterminded by Lewis Strauss (Robert Downey Jr.), that leads to his dismissal from government service

- Strauss’ interrogation before Congress in 1959, when his appointment as Sec. of Commerce is rejected

Live by the congressional hearing, die by the congressional hearing. That old saw.

Are there too many “gotcha” moments? Too many “reveals”? Oh, so Strauss isn’t a good guy? He’s the main villain? And David Hill, tossed up as a potential enemy, and whose clipboard Oppenheimer sends clattering across a train station floor, and, lest we forget, is played by Rami Malek, he stands up for him? And oh no, Oppie’s wife, Kitty (Emily Blunt), is going to testify, but she drinks too much, and now she’s hemming and hawing and looking down at her lap and maybe itching to get the flask out of her purse as the prosecutor digs in. But wait! She totally turns things around! She makes him look bad and gets the congressmen on Oppenheimer’s side! Yay!

I also don’t get Alden Ehrenreich’s role. He’s supposed to advise Strauss during his congressional hearing but turns against him, or at least roots against him, when he finds out what a jerk he is. I guess he’s just there to signal what we’re supposed to feel. “Chris, what’s my motivation in this scene?” “You don’t have a motivation. You don’t even have a name.”

With all this carping, you’d think I didn’t like the movie. I did. It opened up (as much as anything could) the world of early 20th century quantum physics for me. And it was fun seeing characters excited to see Niels Bohr (Kenneth Branagh). Hell, it was fun seeing someone portraying Niels Bohr. Or Werner Heisenberg (Matthias Schweighöfer), Richard Feynman (Jack Quaid) or Edward Teller (Benny Safdie). And those are just the names I know. Imagine you’re a scientist watching this. It would be like me and “42”: Hey, Clyde Sukeforth! Cool!

So I liked all that and the early amazement at Oppenheimer’s intellect: learning Dutch in six weeks, knowing Sanskrit, reading Proust and Eliot and quoting Donne. And I just loved David Krumholz’s Isidor Rabi, the fellow Jewish-American physicist who humorously chastises Oppenheimer for learning Dutch while not knowing basic Yiddish, then feeds him like a Jewish mother. That’s a supporting role I could’ve seen expanded. I smiled every moment he was on screen. (Rabi’s relatives, apparently, felt otherwise.)

And when Matt Damon’s Col. Groves shows up? So fun. The “We need to get this done by any means necessary so get out of my fucking way” attitude, but with a glimmer in the eye.

Does the movie lose itself about 90 minutes in or did I just get tired? More, does the tripart structure (the trinity structure?) take away from the magnitude of the discovery—the moment when we realized that all that intellect and progress was just leading us toward global destruction? These are its last lines, a flashback to Princeton 1946:

Oppenheimer: When I came to you with those calculations, we thought we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world …

Einstein: I remember it well. What of it?

Oppenheimer: I believe we did.

Then he stares into the void and feels the horror of the accomplishment. Some have criticized Murphy’s performance as too wide-eyed and one-note, and, given everything Oppie did, he does feel passive. But Cillian is amazing for staring into the void and feeling the horror. (Cast him as Col. Kurtz.) But should that moment have been at Princeton 1946? Is there a reason it’s Princeton 1946?

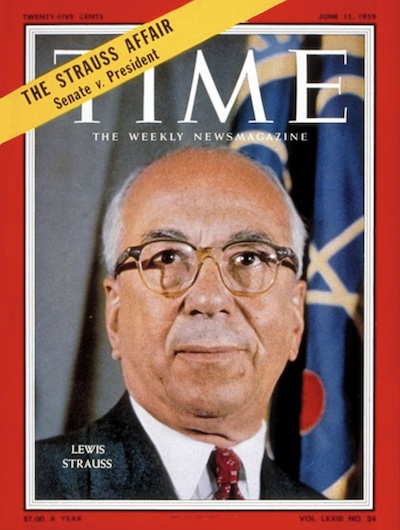

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The constant reference to Oppenheimer’s post-Hiroshima fame is a little odd, too. Before he visits Pres. Truman (Gary Oldman), he sees a TIME magazine cover story on him: Father of the Atomic Bomb. Then Truman greets him with “How does it feel to be the most famous man in the world?” Because of TIME? Oppenheimer’s TIME cover story was actually from Nov. 1948, not Oct. 1945, and its subhed is a little less grandiose: Physicist Oppenheimer: “What we don’t understand, we explain to each other.” He certainly got more famous. According to newspapers.com, “Robert Oppenheimer” was mentioned in seven articles in 1944, and 1,490 in 1945, but it doesn’t top 2,000 much. That’s not exactly “the most famous man in the world.” It’s science fame. He was famous for a scientist. His high-water mark, again per newspapers.com, was set during those 1954 security hearings, when he’s mentioned 22,042 times. You know who was written about more that year? Lewis Strauss: 30,504 times. He’s written about even more in 1959.

The Strauss affair was a huge story at the time, written about constantly, not to mention historically important: the only cabinet nominee between 1925 (Charles B. Warren) and 1989 (John Tower) to be rejected. What I find fascinating? I’d never heard of it. I was born in 1963, sure, but I read a lot of history, and a lot about that period, and … nothing. Even in Robert Caro’s thousand-page tome, “Lyndon Baines Johnson: Master of the Senate,” it’s mentioned only once, and off-handedly, not to mention parenthetically. In the lead-up to 1960, LBJ had to placate both right-wingers “and the great Senate bulls (he paid off a lot of debts to Clinton Anderson by cooperating in Anderson’s efforts to defeat President Eisenhower’s nomination of Lewis Strauss to be Secretary of Commerce…”).

Should that have been the lesson of the film? If your power stays in the shadows, your legacy might, too? Or is that too “Amadeus”? Oppenheimer’s name continues to resonate while Strauss’ winds up in the dustbin. “Do you know nothing of my music?” It might’ve helped if Strauss had made music.

Teller’s hand

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

“Why aren’t you fighting?”

Kitty says this (repeatedly?) during the ’54 hearings, but it seems an odd question since Oppenheimer is never portrayed as a fighter. He’s a scientist who somehow falls into the Manhattan Project gig. (The film assumes he’ll get it—because he does—but I’m curious who else Gen. Groves considered, and why, in the end, he went with Oppenheimer.) Oppie’s a man with an open mind who listens to everyone around him and tries to keep the group together. Teller wants to work on his H-bomb theories? Sure. Have at. He’s a diplomat.

But since the film raises the question, what’s the answer? The obvious one is he feels the need to pay for his sins: A-bomb, Hiroshima, bringing us into the nuclear age, destroying the entire world.

I’m curious why he didn’t make more of the thin window between the end of the war in Europe (early May 1945, when our need for the A-bomb kind of ended) and the Trinity test (July). Was there too much momentum? I get the political calculus: You save countless U.S. GI lives and send a warning to the Soviets. But what was Oppenheimer’s calculus? To just see it through? Was it a bit of Stockholm Syndrome? He’d drunk the military Kool-Aid? Or did he, the perennial theorist, just want to see if it would work? Because if he’d wanted, he could’ve put the kibosh on it pretty quickly. Just resurrect the whole “Yeah, we might set the entire atmosphere on fire” scenario. “What are the odds of that?” “Oh, less than 10%.”

The most famous line Nolan has ever written, or filmed, is probably from “The Dark Knight”: You either die a hero or live long enough to see yourself become the villain. Back in 2008, that felt like bullshit to me—in the film it comes out of nowhere—but, man, the times have proven it true. “Oppenheimer” adds an addendum: resurrection. For a time, J. Robert is the hero. But he lives long enough, and through reactionary times, to become the villain. Then the times shift again, his enemies are smited, and in the 1960s his wife stares daggers at Edward Teller’s proffered hand.

I suppose I should finish the book—it might answer some of my questions. I got 200 pages in last summer but got distracted. Either way, I’ll always have a fondness for the film. It’s the last movie I ever saw with my brother.

Saturday March 09, 2024

Movie Review: Poor Things (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Is “Poor Things” the funniest movie of the year?

It starts out trading elements of “Frankenstein,” “The Island of Dr. Moreau” and some 19th-century gee-whiz wonder emporium—a pre-Great War belief in science and progress, before all the pop-culture scientists became mad and all the real-life progress became radioactive. Then Mark Ruffalo shows up and it’s the funniest movie of the year. The ending? A little too “Freaks” mixed with feminist self-satisfaction for me. But still OK.

The movie is basically a picaresque, and, as such, deserves a superlong subtitle out of the 18th century: “Being of the erotic and philosophical adventures of Bella Baxter, a rogue and foundling.” It’s beautiful to look at and completely unique.

But does it mean anything?

Poor Max

Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe) is a 19th century Scottish doctor/scientist who operates/educates out of a London medical theater with arena seating, where he suffers no fools and draws at least one acolyte, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef), whom he subsequently hires as an assistant. If Godwin suggests Dr. Frankenstein, his face, a patchwork of deep scars, suggests Frankenstein’s monster. Before he was experimenter, you see, he was experimented upon. By his own father. Who, among other things, made him a eunuch.

Godwin Baxter (Willem Dafoe) is a 19th century Scottish doctor/scientist who operates/educates out of a London medical theater with arena seating, where he suffers no fools and draws at least one acolyte, Max McCandles (Ramy Youssef), whom he subsequently hires as an assistant. If Godwin suggests Dr. Frankenstein, his face, a patchwork of deep scars, suggests Frankenstein’s monster. Before he was experimenter, you see, he was experimented upon. By his own father. Who, among other things, made him a eunuch.

Maybe that’s why, despite everything, the movie never loses sympathy for him.

The enclosed grounds of Baxter’s estate are populated, Max finds, by creatures out of one of those flipbooks where you match the heads, torsos and legs of different animals. Here it’s bulldog/goose, duck/goat, pig/chicken. Then there’s Bella Baxter (Emma Stone), a full-grown woman who cannot walk or talk properly, and who pees on the floor without embarrassment or awareness. “My, what a very pretty retard,” Max says. It’s his job to educate her, and she seems to learn freakishly fast. She goes from wondering about the places of the world to climbing to the rooftop to see what lies beyond the gate of the mansion.

She’s a prisoner, Max finds out, and an experiment. That opening scene of a woman jumping off a bridge in London? That was Victoria Blessington (also Emma Stone), who was pregnant, and Baxter animates her body with the brain of her infant, which is why she acts as she does. He keeps her on the grounds, he says, because he needs a controlled environment in which to gauge her progress. But as she chafes against these strictures, he seems to pivot. He allows—even suggests—a marriage proposal from the besotted Max. Then he brings in a lawyer, Duncan Wedderburn (Ruffalo), to make sure everyone agrees to the terms. Everyone does. Except Duncan.

He's a rake, with, as the housekeeper Mrs. Prim (Vicki Pepperdine) says, the scent of a 100 women on him. “She undersells it,” he responds vaingloriously when he hears. Enamored, ready for another conquering, Duncan whisks Bella away to Lisbon. She’d already begun her own sexual adventures, onanistically, and these continue with Duncan. Part of the humor in the middle section is the straightforward way she talks about it all. She calls fucking “furious jumping,” wonders why people don’t do it all the time, and when Duncan begs off after three rounds, laments the physiological weakness in men. On a cruise, she introduces an older woman, Martha von Kurtzroc (Hanna Schygulla, Maria Fucking Braun herself), as someone who has not fucked in years, and then adds, “I hope you use your hand between your legs to keep yourself happy?”

But what’s fantastically funny is how she undoes Duncan by outdoing him. He considers himself a free spirit and libertine who scoffs at the conventions of polite society, but she is all of this many times over. When she doesn’t like food, she spits it out. “Why keep it in my mouth if it is revolting?” she says. She is impolite in polite company and insistent on new experiences. The more he tries to grasp her, the further away she gets away. “I have become the very thing I hate,” he admits at one point. The humor is in his frustration, his slow-burn jealousy, and his creeping awareness of what a conventional man he really is. One night she finds him at a bar, where he admonishes her for spending time with another man.

Duncan: Did he lie with you?

Bella: No. We were against a wall.

Duncan: Did you furious jump him?

Bella: No. He just fast-licked my clitoris. I had the heat that needed release, so at my request it was.

[Duncan bashes head against bar]

Duncan is vain, Ruffalo is glorious.

Bella’s education moves beyond the sexual to include food, drink, music and philosophy. She meets a cynic, Harry Astley (Jerro Carmichael), who shows her the deprivations of the world in Alexandria. Distraught, she bankrupts Duncan with money that, yes, doesn’t wind up with the poor anyway, and the two are set ashore in Marseilles and wind up penniless in Paris. There, Bella resorts to prostitution. That sounds like comeuppance, but for her it’s almost a win-win: a place to experiment with other lovers while making the money to survive. The sex is both graphic—for a mainstream film—and fantasy, in that pregnancy or disease never really enters into it. Maybe she can’t get pregnant? I think that might be implied at one point. She returns to London when she finds out her creator, Godwin, whom she calls God, is dying (of cancer) as the 20th century is set to begin.

An important character is introduced at the 11th hour, Alfie Blessington (Christopher Abbott), the former husband of Victoria. With Duncan in tow, or alternately hiding behind him, he interrupts Bella’s marriage to Max with the announcement that Bella is in fact already married to him. Upon hearing the tale, Bella agrees to go with him for the same reason she does most things in life: to find out answers. She’s truly Godwin’s daughter in that respect.

And she finds the man is surely insane. He pulls rank stunts on servants, levels guns at them at all hours, and expects Bella to get a clitorectomy. No wonder Victoria threw herself off that bridge. But Bella, as she is wont to do, turns tables. She tosses the drugged drink in his face, the gun goes off on his foot, he passes out. And this is when she truly becomes Godwin’s daughter. His foot is repaired but so is he: He’s given a goat’s brain. What happens to his own? Is it put into the goat? Did they try to film that and it was too creepy? Either way, I pity the poor goat. It doesn’t want a human body. Imagine the first time it tries to jump.

But this is our feel-good feminist end: Bella presiding over the grounds and its mostly female denizens: Toinitte (Suzy Bemba), her Black, Parisian prostitute friend/lover; a second Bella experiment, Felicity (Margaret Qualley); and Mrs. Prim, Oh, and Max, of course. Poor emasculated Max, poor thing.

Poor Wednesday

So it’s a ride. It’s beautifully photographed—often with a fish-eye lens—and intelligently made. The early shots are in black-and-white, and expand to color once the adventures begin. It’s mostly fantasy, as stated, with race-blind casting. Is that odd given Alexandria? Race issues go away but class issues don’t. Maybe they’re our bigger problem.

I love the principles. On a ship, there’s a dance between Bella and Duncan that is their relationship in joyous microcosm. It’s more battle than dance. Still a child, really, she hears music, begins to dance in unconventional ways, and he, with a desperate smile, tries to segue it into smooth, conventional patterns. And she keeps fighting him. I flashed on the Wednesday Addams dance that made the rounds last year, but Bella makes Wednesday seem like Duncan. Even so, expect a mash-up between the two. I’m shocked it hasn’t been done yet.

Despite the feminist ending, there are inevitable feminist complaints about the film: graphic sex, women with child’s brain, a trio of male creators: director Yorgo Lanthimos, screenwriter Tony McNamara and novelist Alasdair Gray (RIP). It’s still vaginal-forward, unique, beautiful and hilarious. It’s my wife’s favorite film.

But does it mean anything? I keep coming back to that. What’s it all about, Alfie? I thought in the writing, I would write my way to some deeper meaning, but I’m not feeling it. It’s a lark. Even so, more larks like this, please.

Tuesday February 20, 2024

Movie Review: Maestro (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I didn’t like them. Sorry. I thought they were affected and annoying. Or he was affected and she was annoying. I came away thinking they were monumentally privileged people making bad decisions. It felt like watching a couple air decades-long resentments at a dinner party, and that’s not my idea of a party.

“Maestro” focuses on the great heterosexual relationship of a great homosexual, which … sure? It feels like there’s a story there, and I guess this is it, but shouldn’t we have focused more on the music? Or felt the music? The genius of it?

Maybe I’m just tone deaf.

Peanuts

Elliptical is the word that kept coming to mind as I watched. Then I looked up its definition to make sure I was using it correctly.

- : of, relating to, or marked by extreme economy of speech or writing

- : of or relating to deliberate obscurity

I was thinking of the second definition but the first applies, too. There’s extreme economy in scenes—we zip past years and decades, and from black-and-white to color—while there’s deliberate obscurity within the longer set pieces. Or writer-director Bradley Cooper is the first, and actor Bradley Cooper is the second. Characters talk around matters. Do we ever hear the word gay or homosexual? Instead, it’s “You’re getting sloppy.” It’s “Don’t you dare tell her the truth!” Which, yes, is the way people talked about homosexuality back then. It’s also the way couples today and forever talk about the most important things in their relationship. Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre (Cooper and Carey Mulligan) have their shorthand like the rest of us. They have their deliberate obscurity for fear of looking too deeply into the thing.

I was thinking of the second definition but the first applies, too. There’s extreme economy in scenes—we zip past years and decades, and from black-and-white to color—while there’s deliberate obscurity within the longer set pieces. Or writer-director Bradley Cooper is the first, and actor Bradley Cooper is the second. Characters talk around matters. Do we ever hear the word gay or homosexual? Instead, it’s “You’re getting sloppy.” It’s “Don’t you dare tell her the truth!” Which, yes, is the way people talked about homosexuality back then. It’s also the way couples today and forever talk about the most important things in their relationship. Leonard Bernstein and Felicia Montealegre (Cooper and Carey Mulligan) have their shorthand like the rest of us. They have their deliberate obscurity for fear of looking too deeply into the thing.

The movie ends with Bernstein asking an interviewer “Any questions?” and here’s mine: Why does she air her resentments when she does? He announces to the family that he’s finally finished his mass, “Mass: XVII. Pax: Communion,” so why does she jump in the pool, fully clothed, and sit at its bottom like Benjamin Braddock? Shouldn’t the moment be celebrated?

Well, it’s the boy, obviously, Tommy (Gideon Glick). Meeting him at a party at their home in the Dakota, Leonard pats his hair, and kisses him in the hallway outside, where they’re caught by Felicia; then he still him to their summer home. He holds hands with him during the premiere of the Mass. But he’s had his flings before, and she knew who he was when they married. Why is this different?

Because Tommy is less fling than muse. She thought the boys were the sex and she was the love, but they were the love, too. Or at least Tommy is. From an earlier conversation:

Leonard: “Summer sang in me a little while, it sings in me no more.” Edna St. Vincent Millay.

Felicia: If the summer doesn’t sing in you, then nothing sings in you. And if nothing sings in you, then you can’t make music.

And he can’t. He’s a great conductor, a great educator, who’s produced a few great works, but not many, and everyone, particularly him, is wondering where it all is. And then the boy shows up and he finds it. He finds summer. That’s why she dunks herself in the pool and leaves his things in the hallway outside. All the time she thought she’d been helping and then she begins to wonder if it was the opposite. Or maybe she began to wonder, with the women’s movement, “What about me?”

That’s interesting, isn’t it? The second half of the movie is a clash of people who denied what they were, only to be allowed it late in life by worldwide movements—women’s and gay. It comes a bit late for her. The parade passes her by.

Throughout I had questions about his place in American culture. How did his involvement with “Omnibus” happen? How was it received? One assumes well. He educated the populace. The movie gives us Snoopy, small and large, but not the “Peanuts” of it all. Bernstein was there, early on, beloved by Charles Schulz:

I was born in 1963 and LEONARD BERNSTEIN was a name I always heard but didn’t know why. Probably because he did so many things: conductor, composer, activist. Probably because most of what he did was above me. Is. The movie helps with this but not enough. What did he do differently as a conductor? Why did he stand out? The movie feels like it was made for people who know what conductors actually do and that’s not me. It’s not many of us. It’s like we need someone to educate us on it.

Pillows

My favorite scene was after Felicia admonishes—demands—that Lenny not to tell their daughter, Jamie (Maya Hawke), the truth about the rumors she’s heard. So they talk. Father and daughter. It’s the most extended scene with one of his children. Generally he doesn’t seem too immersed in their lives. They’re there, in the background, as he moves through whatever the story is, but here the kid is finally part of the story. So they walk and sit and talk in the usual elliptical manner. And he tells that her people are just jealous.

Jamie: So those rumors aren’t true.

[Pause]

Leonard: No, darling.

Jamie: Thank you … for coming to talk to me. I’m relieved.

And you get this absolute sadness in his eyes. His daughter is relieved he’s not who he really is. It’s heartbreaking. For a moment, it looks like he’s about to come clean, but no. He doesn’t come clean until Felicia bates him to do it. He follows her lead.

I liked a lot of Cooper's directorial touches: how, in the beginning, the long curtains of his bedroom look like the curtains of a stage about to rise; how the note from his daughter floats down to him through the Dakota’s stairwell. I liked the doctor who tells her she has cancer—the way he sits on the stool and holds her hand and breaks the news without bullshit. God, I love this guy, whoever he is. And the scene where Leonard screams into a pillow because she's dying. I’ve been there a lot lately. The pain our pillows have felt.

“Maestro” tries to take in the immensity of the century as it relates to art and culture and politics and sex, and maybe that’s too much for a two hour movie. There’s a lot of talent in the room trying to depict all the talent that used to be in the room, and Lord knows I appreciate the attempt. But the movie gets a lot less interesting to me when she arrives. Then it becomes about them. And I just didn’t care about them.

Tuesday February 13, 2024

Movie Review: The Zone of Interest (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

In case you’re wondering: Yes, Rudolf Höss was the commandant of Auschwitz for much of the war, responsible, in his own telling, for gassing and incinerating 2 ½ million human beings. And yes, he did have that awful haircut.

And in case you need the comeuppance the movie doesn’t give you: In March 1946, he was captured by British soldiers in Schleswig-Holstein. He insisted he was a simple gardener but the soldiers removed an expensive ring he was wearing with his name on the inside band, and there went that. In April, he testified in the Nuremberg trials, then was put on trial in Poland in March 1947. Found guilty on April 2, he was hanged on April 16. At Auschwitz. He was killed near the crematorium where he helped kill 2 ½ million Jews.

Sadly, his wife Hedwig remarried, moved to the U.S., and lived to be 90.

Life is beautiful

As soon as I heard the movie’s concept—what was life like for the family of the commandant at Auschwitz?—I was intrigued. I mostly wondered if it was mere character study or if writer-director Jonathan Glazer (“Sexy Beast”), working from a novel by Martin Amis, focused on a kind of insular drama. They’re living next to the great horror of the 20th century, but they think the story is this—the little drama they’re going through.

As soon as I heard the movie’s concept—what was life like for the family of the commandant at Auschwitz?—I was intrigued. I mostly wondered if it was mere character study or if writer-director Jonathan Glazer (“Sexy Beast”), working from a novel by Martin Amis, focused on a kind of insular drama. They’re living next to the great horror of the 20th century, but they think the story is this—the little drama they’re going through.

It’s a little of both. The movie opens with the family having a picnic near a river, and at one point we see Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) taking it all in, breathing in deeply, and appreciating all he has. Then, damn, back to work. He holds meetings. Efficiencies are suggested. While one furnace is cooling, he’s told, another can be ready. It can be around-the-clock. That makes sense to him. He approves.

At home we see Hedwig (Sandra Hüller) tending her garden. There are chores (mostly done by servants), and getting the kids off to school (ditto), but somebody has to organize all that, and that’s her. New clothes arrive. Or new-old clothes. They’re dumped on the dining room table. Some are kids clothes. Do we want any of them? Hedwig tries on a fur coat and admires herself in a full-length mirror. She has tea with neighbor ladies who talk and gossip. You see this diamond? one says. I found it in some toothpaste. They’re sneaky that way.

That’s the character study. The little drama arrives when Höss finds out he’s been promoted to deputy inspector of all concentration camps and the family will be relocated to Oranienburg, near Berlin. Isn’t that good news? No. He doesn’t want to leave. And Hedwig, when she finds out, really doesn’t want to leave. She puts her foot down. He can go back to Germany, she says. Why should they go, too? They’ve built this beautiful life here, amidst the lebensraum Herr Hitler promised (and delivered!), and she’s the envy of everyone who visits. Her mother is envious. It’s theirs. Why should they go? No, they won’t go. Life is too beautiful at Auschwitz.

The movie, or at least this mini-conflict within the movie, is reminiscent of “Meet Me in St. Louis,” isn’t it? But instead of the much talked-about 1904 World’s Fair, there’s the barely talked-about horror next door.

How does this horror manifest itself? In small ways—like in the above ladies-who-lunch dialogue and sorting through kids clothes. There are thrumping nightmares from a sleepwalking child and disturbing closeups of flora. During a weekend excursion in the river, Rudolf steps on human remains. Hedwig’s mother leaves abruptly, apparently horrified by the smokestacks working in the distance, and afterwards a disgruntled Hedwig threatens the housekeeper—reminding her that her husband could turn her into ash. In Rudolf’s office, he schtups a female prisoner, then washes his genitalia in a basement sink. They are being warped by it all, if they didn’t arrive that way.

The great horror

Another question I had going in: Does the movie isolate the Germans, make them an aberration in history, or does it make us wonder what horrors we’re ignoring as we putter around our own (real or metaphoric) gardens? Thankfully, I think it leans toward the latter. At the least, the mood of the movie seeps in. Driving home, my wife commented on how pretty the lights at Denny Park looked, and it sounded like a horrific Hedwig line to me. It sounded wrong—the banality of it. And yes, it’s not the same but it’s enough the same. At the least, we’re all ignoring the great horror just to get through the day.

Höss, although we don’t see his comeuppance, does suffer a bit. After another round of meetings, descending an echoing staircase by himself, he begins to retch. Turns out he’s retching nothing; nothing is coming up. Then we flash forward to present-day Auschwitz: workers silently, methodically, preparing for the arrival of another batch, another trainload—but tourists now, witnesses to the evil we don't see in this movie. Then we flash back to Höss on the staircase. Was this a vision for him? Is that what led to the retching?

See “Zone of Interest” in a movie theater. It’s worth it, but caveat: conversations could be stilted afterwards.

Monday January 29, 2024

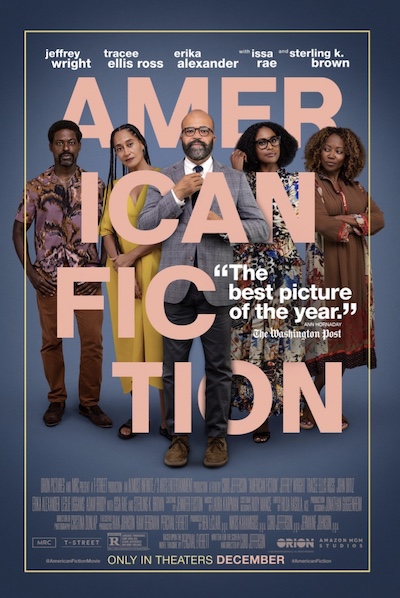

Movie Review: American Fiction (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It’s been a while since I’ve identified with a movie character as much as I did with Jeffrey Wright’s Thelonious “Monk” Ellison, and it doesn’t have anything to do with the movie’s main theme, race, nor with Monk’s own racial attitudes. It has to do with everything else: west coast, separated from family, distant and not just geographically, a writer whose work nobody gives a shit about, and who is, on the wrong side of 55, increasingly grumpy and fed up with the world.

I felt seen.

OK, I’ll bring race into it, too. I am frustrated by all we can’t talk about, or won’t talk about, and it’s a list that feels like it’s growing rather than ebbing. I like that early scene in the college classroom when the white female student objects to the title of the short story they’re discussing, Flannery O’Connor’s “The Artificial Nigger,” which is written on the blackboard in big letters. She’s offended by that. She says so. And Monk sighs and says if he can get past it, she can.

And for that, and other missteps, he’s given a leave of absence from the college.

Here’s some of what I think is going on there. In order for the student to prove her racial innocence, she takes ownership of a word—meant to disparage him—away from him. She gets to own it and hide it away from everyone. And is that what’s been happening in the larger culture? We say “the n word,” rather than what the n word is, not to protect black people but to protect white people.

More offended than thou means more innocent than thou, which is the current game. And it’s getting old.

Heavy lifting

There are two forces pressing in on Monk in the early going: family and monetary needs back home in Boston; and the awful African-American books being elevated by white culture, such as “We’s Lives In Da Ghetto” by Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), while his own novel, an adaptation of Aeschylus, is deemed “not black enough” and can’t find a publisher.

There are two forces pressing in on Monk in the early going: family and monetary needs back home in Boston; and the awful African-American books being elevated by white culture, such as “We’s Lives In Da Ghetto” by Sintara Golden (Issa Rae), while his own novel, an adaptation of Aeschylus, is deemed “not black enough” and can’t find a publisher.

Some of this latter, to be honest, feels a little dated. The novel on which the movie is based, “Erasure” by Percival Everett, was published in 2001, and its author was apparently riffing off of 1990s books like “Push,” by Sapphire, which became the movie “Precious.” And is that still a thing? Also an adaptation of Aeschylus not finding a publisher isn’t exactly a racial problem; it’s wider. There’s a scene, too, where Monk goes into a bookstore, asks after his books, and an employee takes him to the “black” section. Incensed, since there’s nothing inherently black about his books except their author, he grabs an armful and redistributes them, over the hapless employee’s objections, to the classics section.

Thoughts from 2023-24:

- He should be happy there’s a bookstore

- He should be happy they have his books

- He should be happy they have enough of his books—three copies each of four different titles, it looks like—that he can grab an armful of them

That’s the dated thing. Or the ego thing. And the ego thing should’ve been tempered by now. He’s 55. He should know better.

I loved the early conversations with his sister, Lisa (Tracee Ellis Ross), a doctor at a clinic in Boston, who’s been doing the heavy lifting in family matters. Reminded me of my sister and I. They talk through serious issues, like what to do about their mom’s creeping dementia, and they joke and tease like siblings. She is so fun, in fact, and they have such good rapport, I wondered why Monk was so disengaged from his family. And then in the midst of drinks, in the midst of laughter, she has a heart attack and dies, and we’re crushed along with him. Not just because she was a great character but we worry for the movie. Wait, we’re left with just him? Who’s he going to play off of?

But that’s the point: Now he’s got to do the heavy lifting. There’s a line from Leonard Cohen’s “Night Comes On,” that I’ve been thinking about a lot since my brother died, and it fits both me and Monk: “I needed so much/To have nothing to touch/I’ve always been greedy that way.” Now he doesn’t have that remove.

And Mom (Leslie Uggams) is getting worse. The family has a longtime housekeeper, Lorraine (Myra Lucretia Taylor), but she’s getting up in years, too, and anyway she has a new suitor, and by the end of the movie she’ll be married. So Monk looks into nursing homes, trying to figure out what they can afford. It felt like things I’ve done. “Yeah, it’s $5,000+ per month, more for a single, and how do we afford that? And do they just keep taking her money until she doesn’t have any? And then it’s Medicaid? How does it work?”* All of those issues.

(*One way it works is that if it wasn’t for Medicaid, our family would be bankrupt. So thank you LBJ.)

Late one night, drinking, feeling the financial pressure, and tired of the Sintara Goldens of the world, he begins writing his own ghetto-ish story, recreated in his study, between Willy the Wonker (Keith David) and Van Go Jenkins (Okierete Onaodowan, Hercules Mulligan of “Hamilton” fame). It’s supposed to be a fuck you to the literary world, and that’s all it’s supposed to be, which is a little odd. He needs the money, and this is where the money is. Grab it. But I guess this is the way he gets to stay innocent. Because white publishers don’t get the joke; they love the book and want to give him a $750,000 advance. His attempts to sabotage all this goes nowhere.

Along the way there’s a budding romance with a neighbor above his paygrade, Coraline (Erika Alexander), and a budding relationship with his younger brother, Clifford (Sterling K. Brown), whose marriage ended when his wife found him sleeping with another man. He’s out now, and into drugs and drink (despite the six-pack abs), and all of that felt a bit ’90s, too. A Clifford today wouldn’t go the heterosexual marriage route. He’d know who he was.

Peace sign

Does the movie not go deep enough? That was my initial feeling. At one point, both Monk and Golden wind up on a prestigious literary committee that is attempting to diversify, and where he has to rule on his own book, which was published with a punny pseudonym: Stagg R. Leigh. The white people on the committee love it. Golden doesn’t, which surprises him. You can see him thinking, “Wait, I was just doing what you were doing. So why is yours valid and mine not?” They talk about it briefly but she doesn’t know the parameters of the discussion. She doesn’t know she’s talking with the author. That felt like a good, unexplored area: the divide between what she felt was good and not, and authentic and not, in black literature.

Everything spirals away from Monk—but successfully: the book is a hit, it gets picked up by Hollywood, but his self-disgust ruins his relationship with Coraline. Then the movie becomes a kind of satire of Hollywood’s racial attitudes rather than the literary world’s. We get a multiverse of endings. Should it be this? Should it be that? Felt like a cop out.

I like the scene at the end in the Hollywood backlot where Monk gets into the convertible and locks eyes with the black extra in slave gear, eating his lunch, who flashes him the sideways peace sign. Monk nods. There’s a lot in that nod. There’s a lot in Jeffrey Wright’s eyes there.

“American Fiction” was adapted and directed by Cord Jefferson, who also did the recent, great “Watchmen” series on HBO, an ur-superhero tale that introduced the 1921 Tulsa race massacre to most Americans. I look forward to more from him. I’d like him to go back to that opening scene, the white student offended, and drill the fuck down.

Friday January 19, 2024

Movie Review: Asteroid City (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

My wife and I watched “Asteroid City” last September and came away disappointed. “Didn’t quite get that,” was the general feeling.

I recently watched it again hoping for a different reaction.

Nope.

Junior stargazers

What’s the point of the story within the story within the story? Why does it have to be a kind of documentary, with an Edward R. Murrow-esque narrator (Bryan Cranston), talking about playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) and his final play, which is … this movie? How do the extra layers add anything? For me, they mostly detract. They confer artificiality—that Wes Anderson staple. Maybe that’s why he wanted them.

What’s the point of the story within the story within the story? Why does it have to be a kind of documentary, with an Edward R. Murrow-esque narrator (Bryan Cranston), talking about playwright Conrad Earp (Edward Norton) and his final play, which is … this movie? How do the extra layers add anything? For me, they mostly detract. They confer artificiality—that Wes Anderson staple. Maybe that’s why he wanted them.

Right, he does this a lot. The three stories of “The French Dispatch” are three stories from The French Dispatch. In “Grand Budapest,” the story of Ralph Fiennes’ Gustave F. is told through F. Murray Abraham’s Mr. Moustafa. Etc. But this felt a frame too far for me.

The desert town of Asteroid City, pop. 87, hosts an annual Junior Stargazers convention during the coldest part of the Cold War. Atom bombs are detonating in the distance (to shrugs), the military is there to encourage young minds (to beat the Russians), while the townsfolk try to make do. There’s a mechanic (Matt Dillon), who doesn’t seem to be cheating anyone, and a motel manager (Steve Carell), who is selling real estate via vending machines. They are two of the 87. There’s also a diner.

Into this sleepy berg, family station wagon sputtering and clanking and breaking down, come the Steenbecks: father Augie (Jason Schwartzman), a war photographer; eldest Woodrow (Jake Ryan), a Junior Stargazer; and the three daughters, who come off like the witches of “Macbeth,” all toil and trouble. Augie had planned on stopping at Asteroid City for Woodrow, then driving on to California and the estate of Augie’s father-in-law, Stanley Zak (Tom Hanks), but the car trouble necessitates Stanley coming there, which he’s not happy to do. Particularly since Augie has put off his fatherly duty of telling the kids their mother died two weeks earlier.

Another Junior Stargazer is Dinah (Grace Edwards), whose mother is movie star Midge Campbell (Scarlett Johansson). Midge would like respite from the noise and the crowds but gawkers still prevail—star gazers, you could say—even if they’re deadpan stargazers like Augie, who takes a photo of Midge from across the diner. They have bungalows opposite each other, and from open windows flirt in that deadpan Wes Anderson manner. In this way, they draw closer.

I like how all the men, even the self-assured Stanley Zak, buckle a bit in Midge’s presence. This bit made me laugh out loud:

Midge: I do a nude scene. You want to see it?

[Long pause]

Augie: Huh? Did I say yes?

Midge: You didn’t say anything.

Augie: Uh, I mean yes. My mouth … My mouth didn’t speak.

Their junior counterparts, Woodrow and Dinah, also draw closer. All the pretty girls like all the smart boys in Wes Anderson’s world.

You know how young couples become friends through the children? The movie is a bit like that. We meet the families through the Junior Stargazers—though none as well as Augie and Midge. There’s a nice scene where five of our JSes play a memory game around a table. You have to repeat the names that each person has mentioned before adding your own: Cleopatra leads to Jagadish Chandra Bose leads to Antonie van Leeuwenhoek leads to Paracelsus, etc. Most names are long, international, and science-based. I would be out in the first round but they play for days.

The only other real standout among the kids is Clifford (Aristou Meehan), whose bit is to say “Dare me?” and, when no one does, to do the thing anyway. Liev Schrieber plays his father, J.J. Kellogg, a curmudgeon in a porkpie hat, who finally has enough and asks his son the meaning of these dares. It’s a poignant scene. The boy, seeming to reflect on it for the first time, says, “Maybe it’s because I’m afraid, otherwise, nobody will notice my existence … in the universe.” It’s like he recognizes its truth as he's saying it; for the first time he’s wholly vulnerable. His father, too, is touched, and for once agrees to play the game. “Dare you what?” he says. “Climb that cactus out there,” the boy says, pointing. “Lord, no, no,” the father says.

I would’ve liked more of a focus on these families rather than the frame-within-the-frame-within-the-frame. Most of the characters orbit each other from a distance, curious but wary. We’re all junior stargazers.

The muchness

I guess the place is called Asteroid City because an asteroid crash-landed there at some point, and they’re there on its anniversary, and during the celebration, led by Gen. Gibson (Jeffrey Wright), an alien arrives to take the asteroid. That happens about halfway through, and leads to a military quarantine of the place. Everyone is stuck there, but the JSes band together to get word out.

Wes immerses us in all the 1950s Southwest-specific bric-a-brac: from A-bomb tests to road-runners. Apparently he’s said that the quarantine idea wouldn’t have happened without our own COVID-19 version, but our version didn’t involve escapades, and anyway, for me, the alien and the quarantine detracts from everything else: the orbiting, and the curiosity, and the dares. The humanity.

Also detracting is just the wealth of characters and talent in the room. I haven’t mentioned half of them. Maya Hawke plays a young schoolteacher leading kids on a field trip, and Rupert Friend plays a singing cowboy interested in her, and not orbiting at all but actually dancing. Tilda Swinton is a scientist, Willem Dafoe is a German acting teacher with maybe two lines, Margot Robbie plays an actress who had the part of Midge before Mercedes Ford (also Johansson), and who, across balconies, has a scene with Jones Hall, the actor playing Augie (also Schwartzman). It’s the muchness of it all that detracts. I wanted Wes to focus. But all the stars came out.

Monday January 08, 2024

Movie Review: Dumb Money (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I began getting anxious about a quarter of the way in. Took a while to figure out why.

The bad guys are short sellers, men such as Gabe Plotkin (Seth Rogen), who are betting against a company called GameStop during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. They live in mansions, have expensive tastes. They’re not necessarily dicks but they’re not us, either. They float above it all. They’re worth billions. Fuck 'em. (BTW: Is Rogen doomed to play men named Plotkin the rest of his life? Feels like it.)

The good guys are led by Keith Gill (Paul Dano), a working class schlub, who frequents a subreddit called WallStreetBets under the pseudonym “Roaring Kitty,” live-streaming his opinions. And his main opinion is that GameStop is a good bet. “I like the stock!” he says, over and over, without really explaining why a brick-and-mortar company in the midst of the internet/pandemic age is a good bet. Yes, as he says, kids will want to play more video games during a pandemic. But will they visit a store at a dying mall to buy them?

Anyway he convinces a disparate group of the young and working class to join him in his quest to save GameStop and screw over the short sellers. Among the ones we see:

Anyway he convinces a disparate group of the young and working class to join him in his quest to save GameStop and screw over the short sellers. Among the ones we see:

- Jenny (America Ferrera), a nurse in debt

- Marcos (Anthony Ramos), a GameStop employee

- Riri and Harmony (Myha’la and Talia Ryder), two hot college students in debt

They all invest, mostly via an app called RobinHood. And the stock goes up! They’re not only beating back the bad guys but getting rich! Some are up a quarter mil! Gill is a millionaire!

Here’s the problem. Their strength is holding the line as a group, but they can only get at this money, at this prize, if they don’t hold the line—if they cash in as individuals. The scheme, as portrayed here, was built to fail. It was pretending an individual game (Wall Street) was a team game. That might work for a time, particularly if people are in it for laughs, but all bets are off when real money enters the fray.

And that’s why I was feeling anxious.

Unmerry unpranksters

Maybe the anxiety was also this: Is this even a good thing? GameStop’s stock was worth a few bucks in 2019, rose to about $20 when this all started, and reached a peak of … wait for it … $483 a share in late Jan. 2021. Is that an accurate valuation? The movie doesn’t care. “Woo woo, screw the jerks! Power to the people!”

Hell, what we see of GameStop? The demands store manager Brad (Dane DeHaan) makes of employee Marcos Garcia (Anthony Ramos) about pushing secondary products, etc.? They seem like a typical asshole corporation run by people without vision. I’m not even talking about poor Brad. He’s not making these policies; he’s just a middle man. But the movie, and Marcos, treat him as a villain, too. It’s another example of the film’s short-sightedness. (Nice seeing Dane DeHaan again, even in a small, unsympathetic role.)

In real life, wasn’t there more of a snarky vibe to this GameStop business? Most of the investors were in it for a laugh, right? They were anarchic pranksters thumbing their noses at the system. Here, most are true believers. They're dull and stolid. Thanks, no thanks.

Once Plotkin realizes he’s losing playing solo against a team, he rallies his own team, including hedge fund managers Ken Griffin (Nick Offerman) and Steve Cohen (Vincent D’Onofrio), who are initially amused at his predicament, and then alarmed as they get sucked into the morass. At one point, the RobinHood app, run by Vlad Tenev and Baiju Bhatt (Sebastian Stan and Rushi Kota), stops working. You can’t buy GameStop stock on it; you can only sell. A glitch? Collusion? Either way the app boys come off as empty vessels who are in over their heads.

But fortunes are made. The college girls sell high. I guess Marcos does the same, though we don’t see that. Jenny, the nurse, gets screwed over. She’s too loyal to Keith and the stock. She’s too loyal to someone she doesn’t know and something she doesn’t use.

My old friend

I like Keith’s speech, via Zoom, to a congressional committee, on how we act like we know how Wall Street works but we don’t. We don’t get shorting. We’re the suckers. We’re the dumb money. World without end.

The movie’s happy ending (for everyone but Jenny) implies that the hedge funds now have to pay attention to the dumb money because this kind of pile-on—this very specific social-media pile-on—could happen again. I guess? Not satisfying, though.

I’m curious what this movie could’ve looked like with a 1970s sensibility; if writers Lauren Shuker Blum and Rebecca Angelo (“Orange is the New Black”), and director Craig Gillespie (“I, Tonya,” “Million Dollar Arm”), and all of the production companies associated with its making (Columbia, Sony, Black Bear, Ryder, Stage 6), hadn’t insisted on a happy ending. If it had allowed its heroes to be dicks and pranksters using the tech to have a smile at the expense of the suits. If it had been ambiguous about its morality. If, in the end, Keith had given us an uncertain look in the back of the bus while Simon & Garfunkel played on the soundtrack. Hello darkness, my old friend.

Thursday January 04, 2024

Movie Review: Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I might not have been in the right mood for this. I saw “Aquaman and the Lost Kingdom” alone on Christmas Day at the Southdale Theater, about one month and half a mile removed from the murder of my brother at a bus stop on 66th and York Ave. in Edina, Minn. We were two days from his memorial and half the family was dealing with COVID. My step-mom got it, then my 91-year-old father, and several of us had been exposed, including my wife and I, so the two of us moved to a hotel in downtown Minneapolis to keep from exposing others. That was on a Wednesday. Saturday my wife tested positive, and we went to urgent care for paxlovid—which she couldn’t get because she was on antibiotics—and for a PCR test for me. Turns out I was negative. So I switched locations yet again to my deceased brother’s place in Richfield. The next day was Christmas. What do you do when it’s Christmas, your brother’s been murdered, and everyone in the family is social distancing? A movie sounded like a not-bad idea. I actually wanted to see other movies: “Boys in the Boat” maybe (but it was sold out at the Edina Theater), or “Wonka” maybe (but it was playing at the wrong time at Southdale), so I opted for this thing. Last choice on one of the worst days in the worst year of my life.

So I might not have been in the right mood for it.

That said, I only wanted what Hollywood was built on delivering: “Please make me forget for two hours, please.” Instead, I was almost happy to remember the horrors of my world because at least I could leave the stupidity of this one.

Pee in the face

“Lost Kingdom” is the last film in the DCEU, the interconnected superhero world Warner Bros. commissioned in the wake of Marvel’s triumphs and then handed off to Zack Snyder, a writer-director with neo-fascistic and douchebag tendencies. I thought hiring Snyder was a bad move when they announced it in 2010 and history hasn’t proven me wrong. At the same time, he did aspire to some kind of visual artistry. There’s no sense of aspiration from this thing other than to make money before the world ends.

“Lost Kingdom” is the last film in the DCEU, the interconnected superhero world Warner Bros. commissioned in the wake of Marvel’s triumphs and then handed off to Zack Snyder, a writer-director with neo-fascistic and douchebag tendencies. I thought hiring Snyder was a bad move when they announced it in 2010 and history hasn’t proven me wrong. At the same time, he did aspire to some kind of visual artistry. There’s no sense of aspiration from this thing other than to make money before the world ends.

Aquaman (Jason Momoa), forever called Arthur Curry by Snyder & Co., is now King of Atlantis (I’d forgotten), and father, with Mera (Amber Heard), to a new baby boy, Arthur Jr. Much of the opening is cutesy stuff for idiots. The baby is forever peeing on him during diaper changes, for example. One time, he dodges the stream but Mera redirects it—cause it’s water?—so it gets him in the face again. She laughs, the baby gurgles, and our hero gets a wuh-wuh look on his face. If that’s not bad enough, it felt like Momoa and Heard weren’t filming together. We'd see him and the baby, then her, then him and the baby. Apparently CGI can make underwater kingdoms but can't put two actors in the same shot.

Arthur doesn’t like being king—it’s a lot of blah blah, and he’s hampered from doing good work by the council—and meanwhile an enemy gathers: David Kane (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II). I guess he was around in the first movie? I’d forgotten. He’s the son of a pirate that Aquaman killed in the first film so he’s bent on revenge in the second one. He and comic-relief Asian dude Stephen Shin (Randall Park) are excavating Atlantean artifacts when a black trident possesses David’s soul, giving him super powers. And hey, guess what? The entity possessing him also wants to destroy Atlantis! Win win.

(Wouldn’t it have been dramatically interesting if the entity possessed someone who liked Atlantis? Like Stephen Shin? But onward.)

The possessed creature, now known as Black Mantis, is bent on stealing and releasing a mineral known as orichalcum, which, in ancient times, apparently overheated the planet. That’s what Mantis wants to do now. And it’s working! While the world dicks around, the oceans heat up. Mantis also steals the orichalcum reserves from Atlantis. That, more than an overheated ocean, is what alerts Arthur Curry to the problem. And it’s decided—by who, exactly?—that to find Kane/Mantis he needs to ally with his brother, Orm (Patrick Wilson), who is stuck in a desert prison after being defeated by Arthur in the last movie. Right. I’d forgotten.

This thing is so stupid, I’ll let Wikipedia describe the next steps:

The two meet with the crime lord Kingfish, who provides information leading to a volcanic island in the South Pacific. While on the island, Arthur and Orm stumble across the black trident, which Orm learns was created by Kordax, the brother of King Atlan and ruler of the lost kingdom of Necrus who was imprisoned with blood magic following a failed attempt to usurp the throne. Realizing the blood of any of Atlan's descendants could release Kordax, the two make their way to Amnesty Bay, where they learn Kane has kidnapped Arthur Jr.

Oh, the exposition. Oh, the undersea travel. What’s important is that Mantis/Kordax needs the blood of an Atlantean, and he/they steal the baby. The baby.

At this point, I was hoping for a 1970s-era “Fantastic Four”/Franklin thing, where the child is more powerful than anyone realizes and takes care of the bad guy on its own. Doesn’t happen. Instead, underwater fights. Mantis does this, Aquaman does the other, Mera shows up to show women are powerful, too. The spirit of the Kordax winds up in the body of Orm but Arthur convinces Orm, through brotherly love or whatevs, to lay down his arms. Then he reveals Atlantis’ existence at a UN conference. I think they were hoping for a Black Panther/Wakanda vibe, but it just comes off as … seriously, nobody cares.

Door, ass, out

You know who I was wondering about throughout? So the villains who are superheating the earth include Mantis (who’s possessed), Shin (who’s torn), and Stingray (Jani Zhao), who’s … gungho? What’s her deal? Doesn’t she realize she’s making the world uninhabitable for her and hers? But she’s gungho to the end. She’s a true believer. She truly believes in the son of a pirate who is possessed by an ancient underwater king. Who wouldn’t be?

Momoa gets a screenwriting credit here because apparently some of this was his idea. That made me flash on “Superman IV: The Quest of Peace.” Star Christopher Reeve wanted his character to handle the existential issue of the day, nuclear weapons, but, partnered with the cheap bastards at Golan & Globus, he just made a mess. For Momoa, it’s global warming and ditto. “Superman IV” also ended that series.

Ultimately, this is the end the DCEU deserves. Now bang, whimper. Ours.

Tuesday January 02, 2024

Movie Review: The Boys in the Boat (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

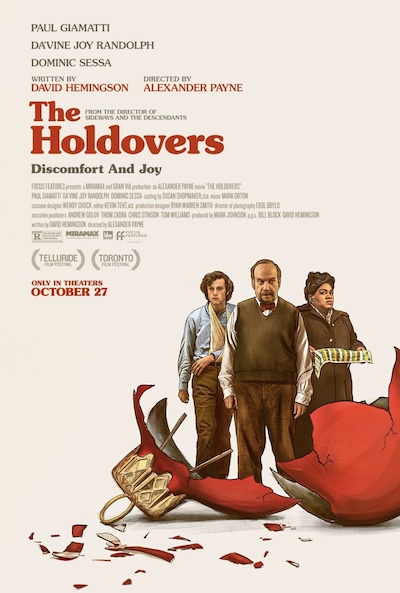

“The Boys in the Boat” is better than its 57% Rotten Tomatoes critics score but not as good as its 97% Rotten Tomatoes audience score. It’s a 65 percenter. It’s OK. I enjoyed watching it. I was moved a few times. I wanted to be moved more.

And not as good as the book, of course.

If you’d asked me when I’d read Daniel James Brown’s account of the University of Washington eight-man crew team that took on California, the east coast elites, and then the world in 1936, I would’ve guessed five years ago. It’s been 10. The book was published in 2013, and I probably read it that year or the next. I actually met Brown, who, per his author bio, “lives outside Seattle,” at the Port Townsend Film Festival in Sept. 2014. They’d asked him to host the showing of a favorite movie and he’d gone with … wait for it … “Breaking Away,” one of my all-time favorites. How could I not attend? It’s easy to see why the author of “Boys in the Boat” might choose “Breaking Away,” too. Both concern a team of young, working-class men who band together to win a race against incredible odds. I believe the announcer of the Little 500 even says something like that: One man may be exceptional … etc. etc. It takes a team.

In “Boat,” the teamwork requires an almost mystical precision.

About the boat

I don’t get some of the storytelling decisions by (I assume) director George Clooney, screenwriter Mark L. Smith, and probably suits at MGM or whatever suits own MGM. Maybe it was a matter of time and money? Those old standbys. Not having enough of either.

I don’t get some of the storytelling decisions by (I assume) director George Clooney, screenwriter Mark L. Smith, and probably suits at MGM or whatever suits own MGM. Maybe it was a matter of time and money? Those old standbys. Not having enough of either.

Why bookend it with an elderly Joe Rantz in the 1970s watching a nondescript crew team—as well as his own grandson in a one-man boat—dealing with the wakes created by a big loud motorboat? That’s not nearly as poignant as Brown’s own prologue about meeting the elderly Rantz, realizing the story he has to tell, and saying he’d like to write about it. Because it leads to this:

Joe grasped my hand again and said he’d like that, but then his voice broke once more and he admonished me gently, “But not just about me. It has to be about the boat.”

I mean, that’s everything right there.

In the film, when we return to the 1930s, we see young Joe Rantz (Callum Turner, hunky) struggling to survive in a Hooverville in Seattle in 1936. I had two immediate thoughts:

- The Hoovervilles of 1936 sure look like the homeless encampments of today.

- Wait, 1936? And he’s not on the team yet?

In the book, and in life, Joe Rantz was actually recruited by Coach Al Ulbrickson (Joel Edgerton) from Roosevelt High School in 1933. Joe wasn’t thinking college until the offer came. That’s why he went. Then he and the freshman class of the 1933-34 crew team did amazing things. They rose and fell. They struggled. It took awhile to get in sync. That doesn’t happen overnight.

In the movie it kinda does. In the movie, Rantz and the others join the team—to have a place to live and maybe some meals—and within a six-month span take over the world. It's as if the Beatles didn't need Hamburg or the Cavern Club. It's as if they didn't need their 10,000 hours.

I get truncating history for a two-hour film but here they also truncate the drama. The real drama, the real story, is how Joe has to unlearn what his own backstory had taught him about life: that he can’t rely on others. His mother died when he was young, his father remarried, his stepmom didn’t like him; and when his father decided to move the family to another state to find work, they didn’t take him along. As the car pulled out, his half-siblings were like, “Where’s Joe? Where’s Joe?” Left to fend for himself, kids. He was 14.

But he fended. He put himself through high school and got the college gig. Then he had to be part of a team. He had to trust—implicitly trust—and that took awhile. And we get some of that struggle in the movie, but it shows up oddly, and it’s intercut with a romance with a pretty girl (Hadley Robinson), who flirts with him like he’s George Clooney.

All of this comes to a head before the Poughkeepsie Regatta. In Seattle, Joe sees his old man again, who's returned to Seattle but still wants nothing to do with his son. Maybe before he saw Joe as the cast-off, and now he sees himself as the cast-off, with Joe getting his picture in the newspaper and all, or maybe he just feels way too guilty, but he says he’s fine with each of them going their own way. Does this gnaw at Joe? Anew? On the train platform, the pretty girl tells him she loves him, and he seems to not hear, but then returns to kiss her. So good, right? Except on the train, teammate Chuck Day (Thomas Elms) kids him with an unflattering nickname. Cottonwood Joe? Palooka Joe? No. Something that implies he’s poor. And they come to blows. But then Chuck apologizes and says his family only has money because they steal it. So he’s the same as Joe except he steals while Joe is honest. It’s a nice apology. So good, right? No, this is exactly when Joe goes out of rhythm with the team and is nearly replaced at the 11th hour. But then we get a version of that great scene from “An Officer and a Gentleman (also Pac NW), in which Richard Gere breaks down and admits he’s got nowhere else to go. That’s Joe to Coach Ulbrickson. But it’s mild. It’s everyday. It doesn’t really land.

The advice that turned Joe toward the right path came from George Pocock (Peter Guinness), the man who built the shells the UW team races in, whose designs were ahead of their time, and who was in fact a kind of father-figure to Joe. They have a few scenes together. These also don’t quite land the way they should.

The losing of self

As the movie progresses, what is the conflict? Where is the drama? Basically this:

- Will Joe get kicked out of school or make the team? He makes the team!

- Will the kids beat Cal? They do!

- Is Coach’s decision to elevate the JV squad a good one? It is!

- Can Joe rejoin the team? He can!

- Will they beat those east coast elites? They will!

- Will they beat the Nazi bastards despite a bullshit lane assignment and a sickness befalling their strong, silent anchor Don Hume (Jack Mulhern)? Yes! In a literal photo finish!

Most of the above actually happened, but, again, liberties are taken. Don Hume’s sickness was respiratory rather than flu-like. Coach elevated the JV squad, but at the beginning of the 1934-35 season and then snatched Poughkeepsie away from them. (If the boys are eight hearts beating as one, Coach Ulbrickson sometimes comes off as arrhythmia.)

Maybe there’s not enough Pocock in the film? In the book, his Zen-like quotes begin each chapter: Example: “What is the spiritual value of rowing? … The losing of self entirely to the cooperative effort of the crew as a whole.” What’s odd is that the team-effort thing is so much better communicated in the book, which is mostly a one-man job, rather than in the movie, which is wholly a team effort.

Will Clooney ever make a movie that wows? Did he ever? I remember liking his first, the Chuck Barris thing. His next, “Good Night, and Good Luck,” was a 2005 best-picture nominee, but it was merely OK for me and feels like it’s faded from view. “Ides of March” wanted to be a 1970s political/paranoid thriller and wasn’t. “Monuments Men” wasted great source material and an all-star cast. “The Tender Bar” felt too surface. Ditto this.

Clooney does one thing I like. Back in 2014, reading about that last race in the Olympics for the gold, against the Brits, Italians and Nazis, I found myself all but rowing along. Brown describes the tension and the drama of the four-mile race so well that my body was literally moving back and forth in bed as if I were the ninth man in the boat. And that’s the moment Clooney puts us in there. The camera rows back and forth with the eight, and so do we. It’s a moment. I wish the movie had more of them.

Well, we’ll always have the book. They can’t take that away from us. Yet.

Monday December 18, 2023

Movie Review: Godzilla Minus One (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Japan’s “Godzilla Minus One” is a huge step-up from the recent Hollywood Godzilla movies but that’s not hard; those were all pretty awful. Each one was a soap opera interspersed with attacks by a giant prehistoric lizard. Here, we get a character study … interspersed with attacks by a giant prehistoric lizard. Much better.

Shame about the ending, though.

Godzilla as metaphor

It’s the final days of World War II, and kamikaze pilot Koichi Shikishima (Ryunosuke Kamiki) lands his plane on the crater-filled runway of Odo Island for repairs. Except head mechanic Sosaku Tachibana (Munetake Aoki) finds nothing wrong with it.  Shikishima is quiet, burdened; it’s obvious he couldn’t kill himself for the Japanese empire. As he gazes at the horizon, carrying the weight of his guilt, he notices odd, deep-sea fish surfacing en masse.

Shikishima is quiet, burdened; it’s obvious he couldn’t kill himself for the Japanese empire. As he gazes at the horizon, carrying the weight of his guilt, he notices odd, deep-sea fish surfacing en masse.

That night, when Odo is attacked by a giant prehistoric lizard the islanders call “Godzilla,” Tachibana orders Shikishima to get into his plane and fire his weapons at the monster. (Why is he so sure this will work? Who knows? Just play along.) Shikishima is actually brave enough to run to the plane but can’t bring himself to fire the weapons, and when he wakes the next morning, everyone but he and Tachibana have been killed. Tachibana hands him photos of the men whose lives his cowardice lost and curses him forever.

Twice coward now, Shikishima returns to a fire-bombed Tokyo, where he finds his childhood home razed and his parents dead. A neighbor lady, Sumiko Ota (Sakura Ando), who lost her own children, sees the kamikaze pilot alive, puts two and two together, and blames him for Japan losing the war. Thanks, lady.

I’d assumed that all of this was prologue, and at some point we’d cut to modern-day Japan, but no, the movie stays post-war. It’s both period piece and a kind of meta explanation for the Godzilla phenomenon. Why, within 10 years of World War II, did Japan make a movie about a giant monster that breathes fire and wreaks havoc from above? Why, indeed? Godzilla is us. Japan woke a sleeping giant, the U.S., that did exactly this. Godzilla could also be the A-bomb—both work as metaphors. To be honest, I never thought much about Godzilla metaphors before, but watching Shikishima and the others struggling to survive in the wreckage, and knowing what’s about to come, well, you can’t help but see the parallels.

In the rubble, Shikishima meets a woman, Noriko (Minami Hamabe), with a baby—not hers—and the three wind up living together in a shack. Platonically. He’s way too traumatized for anything else. Then he gets a well-paying job. Both Japan and the U.S. mined the waters around their island nation, and the new government hires men to remove the mines and blow them up. It’s dangerous work but Shikishima seems to want the danger. The man who couldn’t kill himself wants to die.

The movie is more Shikishima than Godzilla. Our questions about him as the movie progresses:

- Will he fit in with the minesweeping crew? Yes.

- Will he be able to fire his weapons at the mines? Yes—he’s a good shot.

- Will he be able to fire his weapons at Godzilla, newly irradiated and enlarged (and enraged) by the A bomb tests at the Bikini Atoll? Yes.

- Will Tachibana come back to haunt him? Yes, but not to haunt.

- Will he and Noriko find true love? Why not.

There’s a nice “What a hunk of junk” bit with the minesweeping boat, which is made of old, creaking wood. Shiki is told by its oft-bemused captain, Yoji Akitsu (Kuranosuke Sasaki), that the U.S. dropped mines that are attracted to metal. So: wood. The other two crewmembers are the affable former naval engineer with the nice hair, Kenji Noda (Hidetaka Yoshioka); and Shiro Mizushima (Yuki Yamada), who doesn’t realize his good fortune of being too young for war. (I don’t know if Japan went the route of sending teenage boys to war, as the Germans did at the tail end, but I never bought that Shiro was too young to fight. For one thing, the actor playing him is 33.)

Oh, we also get a “Han Solo returns to take out the X-wings” vibe near the end, when Shiro returns at an opportune point to help with the final Godzilla battle. No surprise that, per Wiki, director Takashi Yamazaki was drawn to filmmaking by “Star Wars” and “Close Encounters.”

The film is oddly anti-government. It’s almost libertarian. Governments create problems (see: Bikini Atoll, WWII) but are nowhere on the solutions. This giant irradiated monster is heading toward Japan, and the U.S. is like, “Yeah, we’re busy with Russia now, how about we give you a couple of battleships and you take care of it, thanks.” And it’s not just the U.S. The Japanese government doesn’t want to tell the populace about Godzilla because they don’t want to cause a panic. The fuck? Plus they have no plan. No nothing. They’re not involved. When it’s time to tackle the big guy, it’s a consortium of private citizens.

The big brain of this group is the affable engineer with the nice hair, Kenji, who, because this Godzilla has the power to heal itself like Wolverine, suggests a rapid dunk with freon, then a rapid rise with inflatables, to kill it with decompression. Meanwhile, Shikishima’s got his own plans. During Godzilla’s attack on Ginza, he killed Noriko, so Shikishima plans to do what he couldn’t do during the war: ram a plane loaded with explosives down the throat of the bad guy. Banzai.

Along with “Star Wars” elements, there's a distinct “Jaws” vibe midway through.

33rd and counting

All of that goes down. The decompression weakens Godzilla, then Shikishima does the kamikaze thing and saves the day. Shikishima’s sacrifice is complete; he’s finally at peace.

Wait, what’s this? He ejected at the last minute? With an ejector shown to him by Tachibana? Who wants him to live? And Noriko is alive too? I think even Hollywood execs would blanch at so much happy ending out of nowhere.

Then we’re shown Godzilla regenerating. Because money.

Apparently this is the 33rd (!!!) Godzilla movie from the Toho Co.—i.e., not the Hollywood stuff—and I’ve seen, what, three or four of them? They seem to go in phases—one a year for five years, then nothing for six or nine years. The biggest fall-off in Godzilla production correlated with the Japanese economic miracle: Between 1975 and 1991 there were only two. Was life too good then? Does Godzilla only imperil Japan during moment of crises?

I did like the quiet of this movie. I liked most of what it was trying to do.

Don't worry: Like James Bond, Godzilla will return in an exciting new adventure!

Saturday December 16, 2023

Movie Review: Rock Hudson: All That Heaven Allowed (2023)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Throughout Stephen Kijak’s doc, we get scenes from Rock Hudson’s movies that inform viewers of the real story behind the heterosexual facade. Basically they “Celluloid Closet” his oeuvre.

- In “Bengal Brigade” (1954), Rock’s character informs Arlene Dahl that he can’t marry her. “For a moment,” he says sadly, “I forgot who I am.”

- In the 1957 adaptation of Ernest Hemingway’s “A Farewell to Arms,” an older woman tells him, cheerily, “You’re going to town tomorrow and find yourself some gay young playmate!”

- In 1965’s “A Very Special Favor” he’s told: “Hiding in closets isn’t going to cure you.”

Even the 1950s tabloid press gets into the act:

TWICE BURNED, ROCK KEEPS HIS DATING GAY

One assumes these quotes are taken out of context, but there are a lot of them. Did the screenwriters know what they were doing? Did Rock? When did gay mean gay? When did in the closet mean in the closet? If all of this was done with a wink, they were certainly dancing on the parapet

Maybe everyone just had the urge to say some small truth. Or a large one.

The personification of Americana

Rock Hudson was the biggest male movie star in the final years of the studio system. According to Quigley, he was among the top three box office performers from 1959 to 1964, and No. 1 in ’57 and ’59. Then everything changed. JFK was assassinated, the Beatles landed, and Hollywood, struggling to survive in the TV era, began to cut loose the decrepit Production Code in order to show what couldn’t be shown on television (sex and violence, mostly); to get people out of their homes again.

To be honest, Rock’s movie persona, or the movies he made in his heyday, never interested me in the way that, say, early 1960s Paul Newman movies did. I have no interest in the pillow talk movies, or in Douglas Sirk’s weepies, which cinephiles have elevated over the years. (Martin Scorsese has even given them his imprimatur.) Straight, Rock Hudson doesn’t do it for me. Gay, he’s fascinating.

“Rock Hudson is playing a man called Rock Hudson, who is the personification of Americana,” actress and film historian Illeana Douglas says here. “The identity was given to him. And he slipped into it and played it for the rest of his life.”

I’d go further: He was a gay man playing a macho straight man for a homophobic culture. A tall Midwestern kid named Roy Harold Scherer Jr. went to war, came to Hollywood, and was molded by gay talent agent Henry Willson, who, per the doc, taught his clients how to be heterosexual. Willson fixed teeth and effeminacy, and he gave his boys brawny names: Tab Hunter, Guy Madison, and, yes, Rock Hudson—a name so unyielding “The Flintstones” didn’t know what to do with it. In that cartoon world, Cary Grant became Cary Granite, Tony Curtis became Stoney Curtis, and Rock Hudson became … Rock Quarry? It was a name beyond parody.

Rock was toiling amid early 1950s B westerns and “easterns” when gay producer Ross Hunter hooked him up with Sirk for a remake of the 1935 film “Magnificent Obsession,” which became one of the highest-grossing movies of 1954. It made him a star. Several years later, the Doris Day comedies put him in another realm.

The doc spends a lot of time on his late-career attempt to upgrade to more serious fare, with John Frankenheimer’s “Seconds” (19660, an art film that bombed. What it doesn’t talk about? The roles he took immediately after:

- Maj. Donald Craig in “Tobruk” (1967)

- Capt. Mie Harmon in “A Fine Pair” (1968)

- Cdr. James Ferraday in “Ice Station Zebra” (1968)

- Col. James Langdon in “The Undefeated” (1969)

- Maj. William Larrabee in “Darling Lili” (1970)

In every movie, he’s a military officer in some dull action-adventure. It’s almost a return to his pre-“Magnificent Obsession” career. It was like he went, “Well, that didn’t work.” The Civil Rights Movement and Stonewall were all happening, and Rock was retreating back into the 1950s personsification of Americana.

Was he ever close to coming out? The doc interviews Armistead Maupin, of “Tales of the City” fame, who met Rock in the early 1970s when Rock came to San Francisco to shoot “McMillan & Wife.” Maupin was of the “out” generation, who felt Rock and his friends were slightly ridiculous—“The pride they took in hiding,” Maupin says. “I had a bee in my bonnet at the time. I said ‘You need to come out of the closet, and I’m the guy who can help you with that.’”