Movie Reviews - 2010 posts

Friday September 10, 2010

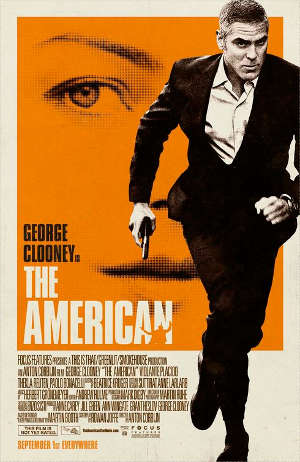

Review: “The American” (2010)

WARNING: COOL, PROFESSIONAL SPOILERS

One imagines they called it “The American” only because “The Quiet American” was taken.

This is one quiet action film. It’s more of a suspense film. The suspense is often: What’s he doing? Who’s that guy? What the hell is going on? Apparently American moviegoers have complained. I’m not surprised. This is a Labor Day movie that requires work, and most Americans go to the movies to not work, to justify their preconceptions, to strengthen their worldview. “Give me a hero who’s handsome and knows everything and shoots second and wins, and let me eat my bucket of popcorn and slurp my soda and imagine I’m him.”

Well, we got handsome anyway.

Last January, Terrence Rafferty had a good piece on George Clooney in The New York Times, in which, of Clooney’s recent roles, he wrote: “He works the territory of 21st-century American normality, playing—now, at 48—middle-aged men who are good at what they do and getting by, for the moment, but are beginning to feel stirrings of doubt and dread.”

Last January, Terrence Rafferty had a good piece on George Clooney in The New York Times, in which, of Clooney’s recent roles, he wrote: “He works the territory of 21st-century American normality, playing—now, at 48—middle-aged men who are good at what they do and getting by, for the moment, but are beginning to feel stirrings of doubt and dread.”

I’d go further. The longer Clooney’s been a star in Hollywood, the more he’s played the cool, distant professional in an unethical business who is thinking of escape, of saving what’s left of his soul. Think “Syrianna,” “Michael Clayton,” “Up in the Air” and now “The American.” I don’t want to be an assassin, a fixer, a man who fires people, an assassin. Do we add movie star to the list? Are these roles a cry for help? Maybe it’s George Clooney who is the cool, distant professional in an unethical business who wants to save what’s left of his soul.

As “The American” starts, Jack (Clooney) seems to be living it up: a cozy, snow-bound cabin, a glass of wine, a naked Swedish woman on the bed. Most men would be happy, but he seems distant. The camera shots aren’t lurid but quiet and serious. There’s already an air of dread.

The two bundle up and go for a walk out on the snow-bound frozen lake. It’s beautiful. Then we get a perspective as if from someone watching them in the nearby woods. A second later, Jack sees footprints in the snow. He’s suddenly on. He looks up, around, then pulls Ingrid (Irina Björklund) to the cover of a nearby rock just as, bewwww!, the first bullet hits the rock. Ingrid is startled and scared, and even more startled and scared when Jack pulls out a gun and shoots the assassin. “Jack?” she says. “Jack, is he dead?” He gives her orders. “Go to the cabin and call the police!” I’m thinking he’ll use this opportunity to get away. Nope. She takes two steps in the snow and he puts a bullet into the back of her head. Later he kills the second assassin, steals his car, travels to Rome, calls the home office. He and Pavel (Johan Leysen) use shorthand. “It’s Jack. I’m here.” They meet at a pasticceria and use more shorthand. “Who was the girl?” Pavel asks. “A friend... She had nothing to do with it.”

We suspected as much but it’s still a shock to hear him say it. He killed her then for what? To save himself? To save his agency? His cause? He seems like a man without agency or cause. He seems like a man full of dread and doubt who keeps doing what he’s doing because he’s on automatic. Pavel makes arrangements for Jack to disappear into a small Italian town, then gives one last piece of advice. “Don’t make any friends, Jack,” he says.

That’s our set-up. A quiet American, traveling through small Italian towns, suspecting everyone, not making friends. It’s a tough set-up. A man needs something to play off of. Drama needs a second actor on the stage. Clooney’s just got... what? His suspicions. He even suspects Pavel. The cell phone he’s given he throws into a river. He switches small Italian towns. You know those modern, high-tech secret agents who can track villains around the world using high-tech gadgets? While running furiously? Jack’s old school. He makes calls from rusty pay phones, reads The International Herald-Tribune in newspaper form, collects car parts to make his weapons. He’s off the grid. Safer there. The movie is based on a 1990 novel by British author Martin Booth called “A Very Private Gentleman,” and that’s what he is. Though more distant than private, more man than gentle.

But we’re social animals. We need. Jack begins to frequent a brothel. Same woman: Clara (Violante Placido). He keeps running into the local priest, Father Benedetto (Paolo Bonacelli), who asks questions in heavily accented Italian. He is curious about this man who is curious about nothing. He encapsulates Jack’s country, my country, in a sentence. “You are American,” he tells Jack. “You think you can escape history.”

Eventually the home office gives him another job. He doesn’t have to kill—apparently he doesn’t want to kill—he just has to make a weapon for another assassin, named Mathilde (Thekla Reuten), who’ll do the killing. She shows up, tests the weapon in some fields, requests refinements. She seems a female version of Jack: attractive, distant, highly professional. One senses Jack’s interest, particularly when, back in the brothel, Clara says he seems different. Is he thinking about something? “Or someone?” she asks with a smile. But the movie doesn’t go there. He spends more time with Clara, and she with him. Is she the luckiest hooker in the world? Not only does her john look like George Clooney but he goes down on her. He takes her out to dinner. They have this conversation:

She: Can I ask you something?

He: Sure.

She: Are you married?

He: No.

She: I was sure that was your secret.

He: Why do I have to have a secret?

She: You are a nice man, but...you have a secret.

He suspects her. He suspects Father Benedetto, too, but accepts a dinner invitation to his house, and gets spare parts from one of his wayward flock, Fabio (Filippo Timi), who, we find out later, is actually the Father’s son. We’re all sinners. We all have secrets.

Where can the story go? That’s the question. Where can Jack go? Toward humanity? Or do his suspicions get the better of him? In a later scene, reminiscent of the first, he nearly kills Clara during a picnic by a waterfall, then holds her close. Maybe this is when he begins to change. It helps that Clara is innocent. But then so was Ingrid.

So Jack moves toward humanity, toward love for Clara, and away from his dirty business. From another rusty pay phone he tells Pavel he’ll make the drop to Mathilde but then he’s out. Pause. “OK, Jack,” Pavel says. “You’re out.” We’ve seen enough of these movies to know the shorthand. Out = dead, doesn’t it? Or are we being paranoid? The drop is done at a roadside cafe. Two tough guys sit by a window. A waitress comes by, then Mathilde, who leaves to check the weapon in a bathroom. Then the two men leave. Then the waitress leaves. Jack is alone in middle of the cafe. Is he alarmed? We are. Get out of there! He does. He meets Mathilde outside the bathroom rather than inside the cafe. They say their goodbyes as a busload of middle-school futbol players pulls up and unloads.

Were we being paranoid? Nope. Pavel later chastises Mathilde for not killing Jack and she pleads a lack of opportunity. But she’ll use the weapon he made to kill him.

Question: Was Jack always constructing the means of his own death? Or did they only target him once he wanted out?

Follow-up question: Did he sabotage the weapon because he was tired of the killing, all killings, or because he knew they would target him? The home office always cleans up around its messes and he knows his mind is one messy place.

I think screenwriter Rowan Joffe and director Anton Corbijn make a mistake bringing Pavel to the small Italian town for the killing. Pavel seems a guy tied to his home office. He doesn’t go out into the field, and certainly not when a killing is underway. So once the weapon backfires and Mathilde dies we know his real purpose there. He’s the assassin now. Sure enough, after hearing Mathilde’s final words (“Who do you work for?” he asks. “Same...as you” she responds), Jack walks down a small Italian street, alone, senses something, turns and fires. Pavel drops, bullet holes in his stomach and forehead. But weren’t three shots fired? Was Jack hit? Corbijn keeps the camera close so we’re not sure, but Jack seems to be walking unsteadily, and, yes, in the car, he’s sweating too much. Yes, he’s been shot. Yes, he’s about to die. But he needs to see Clara one last time.

One of the criticisms of the film is that it’s too brooding, too gloomy, and maybe it is, but what does one expect from a director who photographed this famously gloomy album cover? Besides, the film was consistent in its tone. It reflected its protagonist’s mood.

There are small joys here: the conversations with the old priest, who’s got a great face, and the quiet, efficient way Jack works. Jack is passing himself off as a travel photographer, but the priest surmises, “You have the hands of a craftsman, not an artist,” and he’s right. That’s one of my takeaways from the film: the scenes of Jack expertly building this weapon. The doing of the thing to see if it can be done.

No, the problem isn’t the mood but the resolution: Pavel showing up and Jack getting shot and dying. How much more effective if Jack had gotten away? Because there is no away. He’d still spend the rest of his life looking over his shoulder. Worse, he’d have something (Clara) that he cared about. Worse, the two might have several things (kids) that they cared about. It wouldn’t get any better for Jack, it would only get worse. Some suggestion of this in the final shot would’ve been effective, I think.

I’ll take the end-end, though. Throughout the film, Clara and Mathilde call him “Mr. Butterfly” for the butterfly tattoo on his upper back; and in the final distant shot by the waterfall, Jack’s car rolled to a stop by a tree, Jack dying inside, we see a small white butterfly move up against the darkness of the tree. Is it too much? I liked it. It was subtle enough and implied a lot. After a lifetime of brutality, some small fragile thing was finally set free.

Monday September 06, 2010

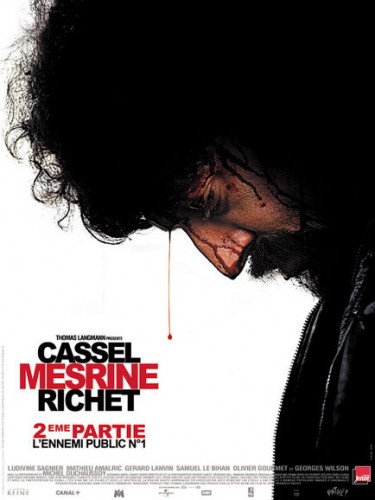

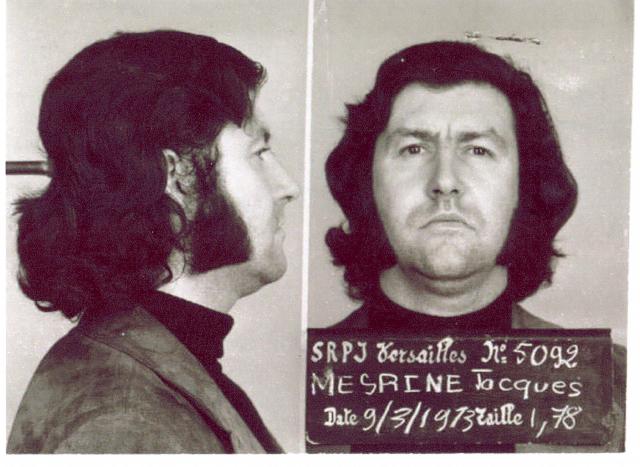

Review: “Mesrine: L'ennemi public n°1” (2008)

WARNING: SPOILERS, PART DEUX

No one has a chance against French gangster Jacques Mesrine (Vincent Cassel).

Which is to say: no one in the audience has a chance to root for anyone else in the movie. He may kill and steal, he may be sadistic and egomaniacal, he may get fat and wear the most ridiculous hair and beard styles of the 1970s, but he’s still the main guy in the movie, the main force, the main man. His eyes are alight. He makes big French meals and gets beautiful French women—sometimes two at a time. He has fun. The cops, in comparison, are beady-eyed things, the journalists either left-wing dupes or right-wing liars, his fellow criminals dull company men. Everyone scrimps, whispers, scuttles. Mesrine booms.

Only once does he meet his match, and that’s when he kidnaps 82-year-old real estate mogul Henri Lelièvre (Georges Wilson). At the grand estate where Lelièvre lives, Mesrine and his mostly silent partner Francois Besse (Mathieu Amalric) pretend to be cops who need to question Lelièvre about some of his properties. Lelièvre is 82 and looks it. He moves slowly, seems fragile. One cringes at the thought of him in the hands of these brutes, and, sure enough, before we know it, he’s sitting on the edge of a cot in a small room, perplexed, wondering what they want with him. Mesrine gloats. They’ve kidnapped him! They’re demanding 10 million francs! Then the fun begins. Lelièvre says aloud, “10 million? I’m 82,” and shakes his head. The businessman in him is insulted at the price even though it’s his own neck on the line. Mesrine is taken aback. He bargains. Eight million? Seven million? In the end they agree to six million over three installments. Lelièvre may be 82 and helpless, but that doesn’t mean he’s going to get ripped off.

The 1970s were an absurd time, both in the states and abroad, and “Mesrine: L'ennemi public n°1,” the second part of Jean-Francois Richet’s nearly four-hour staccato biopic, reflects that absurdity. Against a backdrop of organizations attempting to bring down the system—PLO, Baader-Meinhoff, Red Brigades—Mesrine, an uncommon criminal with a gift for gab, impersonation and escape, passes himself off as a man of the people. In reality he’s just a violent man who can’t bear the 9-to-5 life. We’re intrigued by the second part, repelled by the first, but in the end I still wondered, as I did at the end of part one, “What’s the point? Of all the lives to portray, why portray this life?”

The 1970s were an absurd time, both in the states and abroad, and “Mesrine: L'ennemi public n°1,” the second part of Jean-Francois Richet’s nearly four-hour staccato biopic, reflects that absurdity. Against a backdrop of organizations attempting to bring down the system—PLO, Baader-Meinhoff, Red Brigades—Mesrine, an uncommon criminal with a gift for gab, impersonation and escape, passes himself off as a man of the people. In reality he’s just a violent man who can’t bear the 9-to-5 life. We’re intrigued by the second part, repelled by the first, but in the end I still wondered, as I did at the end of part one, “What’s the point? Of all the lives to portray, why portray this life?”

Part two begins back in France, in 1973, with Mesrine (pronounced May-reen) incarcerated, bragging to the cops that he’ll break out in three months. It doesn’t even take that long. On the way to trial, he claims sickness, needs to use the bathroom. Even as the cops hold onto one end of his handcuffs behind the bathroom door, he, a la Michael Corleone in “The Godfather,” reaches behind the toilet tank to retrieve a revolver his pal left there. He takes it into court and, boom boom, uses it, and a judge/hostage, to escape.

For the first half-hour we get various escapes, where the back window of Mesrine’s car is invariably shot out, and where spectacular car crashes invariably occur but Mesrine’s car invariably limps to safety. Bullets fly but everyone’s a pretty lousy shot. Occasionally one of the bad guys gets winged but that’s about it. Juxtapose these action scenes with a few family reunions. A disguised Mesrine reconciles with his dying father. An incarcerated Mesrine clumsily bonds with his teenaged daughter. Cassel is brilliant in all of this. His own father, actor Jean-Pierre Cassel, was dying of cancer at the time, and the deathbed scene with his on-screen father, who would’ve been played by his actual father if cancer hadn’t reared its ugly head, is particularly intense.

In September ’73 Mesrine is finally captured (again), and in prison he rails against, not the cops or the system, but the Chilean coup that stole his press. “Pinochet, Pinochet,” he complains, flicking his hand at a newspaper. Filling a gap, he demands a typewriter and writes his own memoirs, “L’instinct de mort,” which became the basis for the first part of the film. But it takes him five years to live up to his promise of another escape.

For the rest of the film he complains about maximum security facilities, but we don’t see much of this incarceration so don’t know what he’s complaining about. He meets Besse, a no-nonsense crook who does prison-yard pushups even as Mesrine’s body goes to pot, and they plot escape. But the five years, interminable for him, go like that for us. Plus the escape isn’t that cool. Besse is able to hide a can of mace inside a box of “Petit Beurre,” and when the guards’ metal detector goes off during a routine search they assume it’s the tinfoil packaging and don’t look inside. As for how Mesrine gets his guns? His lawyer brings them. Hardly Andy Dufresne at Shawshank. (Also untrue? According to Wikipedia, guards smuggled in the weapons.)

The larger-than-life Mesrine and the smaller-than-life Besse make a good team. Post-escape, they rob a casino and go on the lam. A stream they’re fording turns out to be much deeper than the optimistic Mesrine anticipated, so he attempts, optimistically again, to toss the loot onto the other side. It splashes in the water, floats downstream, sinks. “That’s your share!” Besse complains bitterly. Then the punchline. He spots a rowboat, 10 feet away, on their side of the river. The fording wasn’t necessary. As an army of men, arms linked, march across a field to capture them, they make their escape via dingy, half their loot unnecessarily, optimistically spent.

“Mesrine” part II contains parallels with part I—Mesrine hooks up with a girl (Ludivine Sagnier), he hooks up with different partners, he kidnaps an old, rich dude—but the most pungent parallel is the kidnapping and near-murder of French journalist Jacques Dallier (read: Tillier, played by Alain Fromager), which echoes, and provides an overall bookend with, the kidnapping and murder of Ahmed the Pimp in “L’instinct de mort.” In both, the victim goes on a car ride with Mesrine and another man. In both, he assumes he’s safe. In both, he’s toyed with in sadistic fashion, then stripped naked, beaten, shot or stabbed, and left for dead. Finally, in both, neither victim is particularly sympathetic. Ahmed is a pimp who beats women; Dallier is a right-wing, racist snitch. Each scene shows Mesrine at his worst.

We needed more such scenes. Not to be too Will Hays about this, but Mesrine was a nasty, opportunistic man, and Cassel is entirely too charismatic to play him so we don’t want to be him. He’s living large, getting babes, talking trash. Sure, he winds up in a pool of his own blood, at the hands of frightened policemen, but he’s our eyes and ears through this world, and he’s the only one having any kind of fun. He’s still the man. As for a larger point in the biopic? It escapes me.

Sidenote: Just as Mesrine’s ’73 capture coincided with the Chilean coup, which stole his press, so his death, on November 2, 1979, occurred two days before Iranian students stormed the American embassy in Tehran and took hostages. One imagines him in the afterlife, complaining bitterly: “Khomeini, Khomeini.” One imagines him demanding a typewriter to set the record straight.

“OK, here's the deal. We escape together, but afterwards I get all the women, the best scenes, and, ultimately, the biopic. D'accord?”

Thursday September 02, 2010

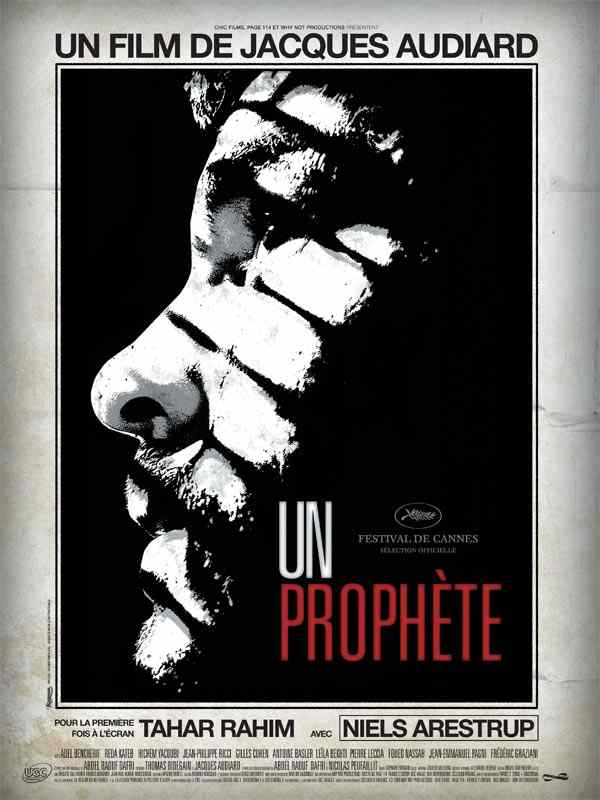

Review: Un Prophete (2009)

WARNING: DEER-IN-HEADLIGHTS SPOILERS

“The idea is to leave here a little smarter,” Reyeb (Hitchem Yacoubi) tells Malik (Tahar Rahim), as the two sit on the edge of his prison bunk and Reyeb stirs his coffee. Reyeb has just found out that Malik, his fellow Muslim, is illiterate, and he’s acting solicitous toward him—suggesting he can always learn to read, telling him he’ll give him some books—even as he’s anticipating a blow job. Instead he gets his throat slit. Guess the joke’s on him, right? Guess he left there a little smarter.

But he doesn’t leave. He remains in Malik’s life—a palpable, matter-of-fact symbol of guilt—and his words linger. And after six years Malik will leave there a whole lot smarter than when he entered. He will leave a prophet. It’s prison as a means to both worldly and spiritual redemption. Kids, don’t try this at home.

“Un Prophete,” which was nominated for 13 Cesars and won nine, including best picture, director (Jacque Audiard), actor (Rahim), supporting actor (Niels Arestrup), writing, editing, and cinematography, is both gritty and uplifting, full of lessons of realpolitik and the unknowability of dreams and life. It’s a movie for anyone who thought nothing more could be done with the prison drama or the gangster life. It’s a film we will still be watching in 50 years.

“Un Prophete,” which was nominated for 13 Cesars and won nine, including best picture, director (Jacque Audiard), actor (Rahim), supporting actor (Niels Arestrup), writing, editing, and cinematography, is both gritty and uplifting, full of lessons of realpolitik and the unknowability of dreams and life. It’s a movie for anyone who thought nothing more could be done with the prison drama or the gangster life. It’s a film we will still be watching in 50 years.

Malik’s life begins when he enters prison. He has nothing but the scars on his face and the 50-euro note he tries to hide in his shoe; it’s found and confiscated. He’s stripped, shaved, given a pillow and a metal tray and a new pair of tennis shoes. In the prison yard, alone, the shoes are big and white and seem to gleam, and a second later he’s attacked and his shoes are taken. He gives back—he attacks his attackers—but gets beaten down again. The odds aren’t good. He’s alone with six years to go.

He might not have made it if Reyeb hadn’t shown up. The prison is divided between Corsicans, who are few but control the guards, and Muslims, who are many but control nothing, and Reyeb, about to testify in a trial against a Corsican, is targeted by prison don Cesar Luciani (Arestrup), whose boss, Jacky, has given him 10 days to kill the snitch. Easier said. Cesar moves through the prison with relative ease but he doesn’t control the Muslim section. Then he hears that Reyeb asked this new kid to suck him off, and, in the prison yard, he makes Malik an offer he can’t refuse: Kill Reyeb or I kill you.

We later learn that Malik didn’t have much of an upbringing. When asked if he spoke French or Arabic with his parents, he responds, “I wasn’t with them.” When asked about school, he replies, “The juvenile center.” We have sympathy for him the way we would a stray dog. He’s scared and confused, but watchful, and back in his cell, after Cesar threatens him, he tells himself, “I can’t kill anyone.” He tries to contact the warden but the Corsicans hear and nearly suffocate him in a plastic bag, saying, “We run this place.” In the sewing shop he joins in a beat-down of a helpless prisoner, hoping to get tossed into solitary, but Cesar hears of this and beats him down. He’s trapped. He has to do this thing.

It’s the palpability of the act that gets you: less the Peckinpahesque spurting of blood from Reyeb’s neck than the goopy way blood and saliva mix as Malik pulls the razor blade from his mouth, where he’s involuntarily cut himself. It’s his careful extrication from the scene: stepping over the blood; placing the razor in Reyeb’s hand; scrubbing the blood from his shirt in the prison bathroom. It’s the disconnect one feels despite this precision. Malik hears someone screaming; he sees flames falling out of a prison cell. What is going on?

Prison life opens up for Malik afterwards. He receives cartons of cigarettes from Cesar (“You’re under his protection now”), and, taking Reyeb’s advice, he learns to read (“Canard: Ca-nard”), but he’s still isolated. The Muslims view him as a Corsican while the Corsicans disparage him as a dirty Arab. His main companion is the man he killed. In his dreams Malik wrestles with Reyeb, as if he were the Archangel Gabriel, and in the morning Reyeb is there, a physical presence. Reyeb is the one who sings “Happy Birthday” to Malik in Arabic on the one-year anniversary of his incarceration. He’s the one staring with him out his cell window as snow falls on the prisoners in the courtyard.

Life opens up even more when these Corsican gangsters, like naughty schoolboys, are separated by powers outside the prison. Perhaps feeling sorry for Cesar, Malik, eyes alight with his secret, reveals that he’s learned Corsican over the years and the conversations he’s been privy to. Cesar stares at him, then hits him. Because he senses the pity? Because he senses opportunism? Because his private conversations weren’t private and this dirty Arab is smarter than he realized? Regardless, he soon comes to rely on Malik more and more, but there is no corresponding sense of respect. He keeps treating Malik like a dirty Arab.

Bad move. Both inside the prison, and outside on work-leaves, Malik makes contacts and accrues power. He gets involved with Jordi, the Gypsy (Reda Kateb), who deals hashish. He becomes friends with Ryad (Adel Bencherif), who is the beginning of his entré into the suspicious Muslim prison community. He does his jobs, straddles both worlds, acts the professional. There’s an unaffected quality to him, an ingenuousness. “Why is an Arab working for the Corsicans?” he’s asked. “I work for who pays me,” he answers. One realizes after a while: He doesn’t lie. He’s polite, and professional, and doesn’t lie. The world he lives in expects lies and he disarms everyone with honesty.

His first work-leave is beautiful. After three years he’s finally out of prison, and as Ryad, who’s done his time, picks him up, Alexandre Desplat’s music, “La sortie,” wells up and overwhelms any attempt at conversation, as if the music were Malik’s emotions. He feels the wind on his face, the sun on his face; then he does a job for Cesar. He gets 5,000 euros to retrieve a Corsican gangster from a Muslim gang. Then he does a job for himself. He retrieves 25 kilos of hash stored by one of the Gypsy’s men. “Five thousand euros and 25 kilos of hash?” Ryad asks him, stunned, when they hook up at dusk. “All in one day?” You know that scene in “The Godfather” where Michael suggests killing the Turk? Where Michael essentially takes over? That’s this. Malik doesn’t respond to Ryad’s question. He simply tells Ryad what they’re going to do:

We get guys to stock and sell. We supply. We use convoys and buy at the source. The Gypsy has contacts. We need three big cars. Paris-Marbella in one night.

When Ryad objects, saying he’s never done this before, Malik responds, “What’s the big deal? Neither have I.”

What do we make of the prophet angle and Malik’s vision of the deer? To what extent do we compare Malik, the prophet, with the prophet Muhammad? Both are orphans. Both get involved in the merchant trade. Later in the film Malik will go into isolation, solitary, for 40 days and 40 nights, and emerge more powerful than ever. One can call him a Muhammadian figure the way one can call Luke in “Cool Hand Luke” a Christ figure. Elements of the ancient religious story are used to tell the tale of a modern prisoner.

Would things have turned out differently, less Oedipal, if Cesar had treated Malik with any kind of respect? Actor Niels Arestrup has a mane of white hair and fierce blue eyes, and initially one thinks of him as a Godfather type, a Don Corleone in prison; but as the movie progresses and one sees his prejudices, his betrayals, his smallness, one realizes he’s more like the Black Hand. He’s the classless oaf that needs to be overcome. It’s Malik who becomes the Godfather. At one point Cesar nearly puts Malik’s eye out, telling him, “People look at you and see me. Otherwise what would they see? Can you tell me?” The implication is that Malik is nothing without him, but the greater implication, which Cesar fears, or is perhaps too stupid to realize, is that Malik is becoming him. Returning to his cell, his eye damaged by Cesar, Malik promises himself “I’m gonna kill you,” just as, earlier, he’d promised himself, “I can’t kill anyone.” It’s the promises to himself that he breaks. He does kill, Reyeb and others, but he doesn’t kill Cesar. He does something worse. He renders him powerless. By the end their positions are reversed: Malik is the prison don, respected in his community, while Cesar is the weak, isolated man in the prison yard, beyond the circle of power. Beyond contempt.

The arc of its story is brilliant but it’s the details that stay with me—such as Malik’s first planetrip, sandwiched between two bored commuters, trying to get a glimpse of the sky out the window. He’s heading to Marseilles for a meeting, at Cesar’s behest, with Brahim Lattrache (Slimane Dazi—one of the many amazing faces in this movie), where, again, he’s the distrusted Arab courier, but where his vision of the deer saves his life. Afterwards the deer meat is washed in the Mediterranean, and Lattrache, eyeing him with new respect, is intrigued by this quiet, honest man who straddles cultures. “Let’s get sucked before you go,” he says, but Malik turns him down. “I’d like to stay on the beach,” he says. He wades out into the water. One senses he’s never seen the sea before. Back in the dark of his prison cell, he takes off his shoe, looks inside, upends it. Sand courses through his fingers.

I’ve seen this movie twice; I feel like seeing it again now.

Malik (Tahar Rahim), left, after earning a place on the bench of Cesar Luciani (Niels Arestrup), in Jacque Audiard's brilliant prison drama “Un Prophete.”

Monday August 30, 2010

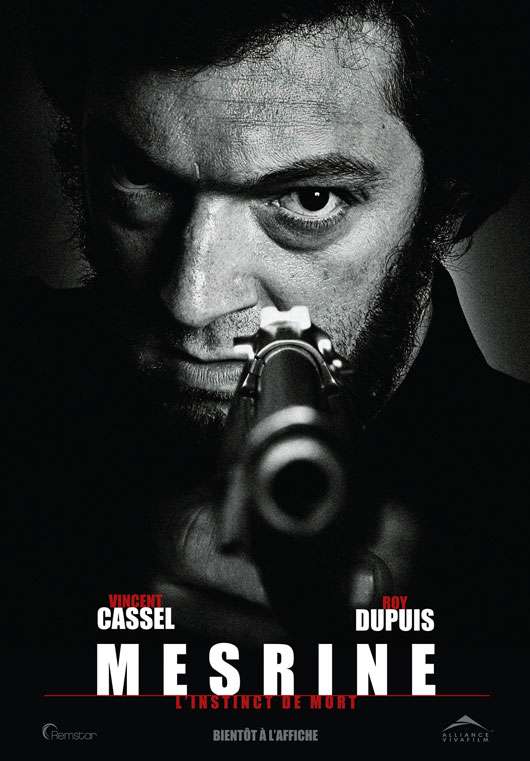

Review: “Mesrine: L’instinct de mort” (2008)

WARNING: SPOILERS, PART UN

“Mesrine: L’instinct de mort,” the first part of a two-part movie on notorious French gangster Jacques Mesrine, which, in February 2009, garnered Vincent Cassel the Cesar for best actor and Jean-Francois Richet the Cesar for best director (but lost best picture to “Seraphine”), and which only now is being shown in U.S. theaters, is a zippy biopic about a brutal man who crammed a whole lot of activity into a short span of time.

At one point, for example, we see him, after an attempted bank robbery, walking into prison. The graphics inform us: Evreux Prison, 1962. His wife and daughter visit him there; he’s overjoyed to see both. He serves his time. When he gets out he goes straight. He gets a job at an architectural design company, working for a man named Tabacoff, has another kid, then a third. But times are tough, Tabacoff has to lay him off, and when he does Mesrine returns to a life of crime. His wife objects. In one scene she threatens to call the cops and he smacks her, then forces a gun into her mouth and tells her, “Between you and my friends, I choose them. Every time.” His young son is watching on the landing above. “Mama?” he says. “Take care of your kid!” Mesrine sneers, and goes out into the world. But his boss, Guido (Gerard Depardieu), tells him times are changing, Pres. de Gaulle is cracking down on their syndicate, so Mesrine has to get inventive. In the next scene he walks into a bar, and the graphics inform us: Paris, 1966.

You’re kidding. Four years for all that? How long does it take to serve time for armed robbery in France? How long does it take to have kids in France?

You’re kidding. Four years for all that? How long does it take to serve time for armed robbery in France? How long does it take to have kids in France?

Initially I feared the film would justify this man’s brutality, and initially it does. In the army in 1959 we see Mesrine shoot and kill a helpless Algerian rebel—but only because his commanding officer ordered him to shoot and kill the rebel’s helpless sister, and this seems the better option. Mesrine berates his henpecked father—who was also a collaborator with the Germans during World War II. Mesrine kills another Arab, a pimp named Ahmed (Abdelhafid Metalsi), but only after Ahmed brutalizes Mesrine’s favorite prostitute. Mesrine’s a defender of women! Until, of course, he goes off on his own wife. But, of course, she threatened to call the cops on him.

At least the brutality throughout isn’t sugarcoated. When Guido and Mesrine take Ahmed for a ride, after promises of safety have been made, they slowly, sadistically, go from polite to insulting. “What do you say to an Arab in a suit?” Mesrine asks. “Defendant, please rise!” he answers, and Guido cracks up, then apologizes, then tells his own Arab joke. Ahmed’s eyes begin to falter as the ride continues. When it ends, in a desolate spot, they brutalize him. They beat him and strip him before an empty grave. Then Mesrine stabs him in his lower back and cuts up. We see the blade go into his skin, we hear Ahmed scream. It’s tough to watch. Finally, they roll him, still twitching, still alive, into the shallow grave and shovel dirt on top. These are not nice men.

At the same time, neither was Ahmed. That’s why we need the kidnapping of millionaire Georges Deslauriers (Gilbert Sicotte). In ’68, Mesrine and his Bonnie-and-Clyde-esque girlfriend, Jeanne (Cecile De France), flee France for Montreal, and she finds them a gig as housekeeper and chauffer to Deslauriers. First we see the beautiful mansion. Then we see the kind, wheelchair-bound Deslauriers. I almost flinched the first time Mesrine pushed Deslauriers toward a pair of French windows, recalling Richard Widmark and a flight of stairs, but for months he simply does his job. Then Jeanne gets into a fight with the gardener, and Deslauriers, taking the side of someone he’s known for 20 years over someone he’s known for three months, dismisses the two. That’s when Mesrine gets angry. In the next scene, he and Jeanne are watching television in a non-descript, high-rise apartment, and slowly we become aware of noises from another room. So does Mesrine. He stands up, pissed off, goes into the next room, and browbeats Deslauriers, who’s tied to a chair, confused and helpless. That’s when I really turned on Mesrine. That’s when I wanted bad things to happen to him. They do.

“Mesrine” is a biopic so it’s inevitably as cluttered as life, but director Richet and writer Abdel Raouf Dafri (who also wrote “Un Prophete”) are remarkably quick and clever with their transitions. My favorite may be early on, when two men discuss an “easy bank job” with Mesrine, who looks doubtful but says, “I’m in.” Cut to: that walk into Evreux prison.

The post-kidnapping transition works well, too. When Jeanne and Mesrine go for the ransom, Deslauriers crawls through the apartment, breaks a window, gets help. The two gangsters return to see cops all over the place. Cut to: the Arizona desert, 1969, as six state patrol cars race after Mesrine and Jeanne in a convertible.

Extradited back to Canada, the two are proclaimed a modern-day Bonnie and Clyde by the counter-culture press, and Mesrine revels in the role. But not for long. In prison, he’s beaten, stripped, firehoused. He suffers sleep deprivation and hunger. I had two thoughts: “Really? Canada?”; and “OK, let’s not make him sympathetic now.” I wanted to hold up a sign: Remember Deslauriers!

Sympathy for Mesrine, or at least transference, is inevitable, though. We see this world through Mesrine’s eyes, he’s played by Cassel, who’s charming and handsome, and he’s doing what most of us sitting in the audience with our bucket of popcorn don’t begin to do: He acts out every impulse. Sure, he winds up in prison. But he also gets money and beautiful women and fame. “I go wherever I want,” he tells Jeanne when they meet. In prison, in fact, they don’t break him, he breaks out, using only his guile and a pair of wirecutters. Then, fulfilling a promise to a fellow inmate, he actually tries to break in. He returns in a Ford pickup truck and shoots it out with the guards. “Crazy Frenchman,” the inmate says, shaking his head with admiration. Mesrine is admired. His life is full. Hell, we’re watching a movie about him, aren’t we? How cool is that?

And yet: Remember Deslauriers!

“Mesrine” is a good film, or half of a good film, but so far it’s not a great film. For one, it’s hard to make biopics great. One also wonders: Why film this life of all lives? Because it’s exciting and absurd? Because audiences are always interested in gangsters, in men who do what they want, because most of us lead lives of quiet desperation? Because this is the way we can get a safe glimpse of what terrifies us—like at the zoo? Are we trying to understand him or be him?

Perhaps we’ll find out in “Mesrine: L'ennemi public n°1,” which, unless Music Box Films is a sadistic distributor, should be available in the U.S. in September.

The real Jacques Mesrine wasn't quite as handsome (or, one imagines, as charming), as Vincent Cassel.

Monday August 23, 2010

Review: “The Other Guys” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS THAT ARE PERKY, FIRM AND YOURS

I had the two biggest laughs of the year while watching “The Other Guys” and neither involved Will Ferrell, who I think is one of the funniest men around. There was a backlash against him last year with “Land of the Lost,” and a bit the year before with “Semi-Pro,” but I liked “Semi-Pro” (more than “Step Brothers,” which did a lot better at the box office: $100 million vs. $33 million), and while “Land of the Lost” was an obvious stumble I figured he’d be back making me laugh again. He is. I’ve been waiting for this movie since the trailer hit the Internet last February.

It’s a great concept for a comedy, and it’s right there in the trailer’s low, gravelly voiceover: In the toughest city in the world, nobody fights crime like these guys... Cue squealing tires, impossible stunts, and nonchalant quips by action stars Dwayne “the Rock” Johnson and Samuel L. Jackson.

Cut to: Det. Allen Gamble (Will Ferrell) typing happily at his desk, humming “The Theme from ‘S.W.A.T.,’” and infuriating his partner, Det. Terry Hoitz (Mark Wahlberg).

And then there are the other guys...

And then there are the other guys...

The other guys are, in other words, the ordinary guys, the misfits, the fuck-ups, forever found wanting in comparison with star cops like Highsmith (Jackson) and Danson (Johnson). They’re us, sitting in the movie theater with our bucket of popcorn, and forever found wanting in comparison with the stars on the screen.

Which brings me to the first of the big laughs.

Highsmith and Danson are on the trail of professional jewel thieves but lose them via zipline on top of a 20-story building. As they stare at the bad guys getting away on the street below, they have this typical action-star exchange:

Highsmith: You thinking what I’m thinking?

Danson: Aim for the bushes.

Then they leap off the roof in slow motion, arms and legs pinwheeling, and the camera follows them down. In the audience I kept wondering why bushes or anything that might break their fall didn’t come into view. And then: SPLAT! Right on the sidewalk. Cut to: A funeral.

Man, did I laugh. I laughed so hard I missed a lot of what followed, and what I caught—Hoitz and Gamble whispering to each other about “What were they thinking anyway?” and “There wasn’t even an awning nearby”—made me laugh all the more. It’s always dangerous dissecting humor, but I think this scene is funny because it’s both unexpected and it lays bare the lie of 100 years of Hollywood action movies. They really can’t really do what they do.

The laughs keep coming. After the funeral, during the quiet dignity of the wake, the cops, particularly Martin and Fosse (Rob Riggle and Damon Wayans, Jr.), now jockeying for the high position Highsmith and Danson held, whisper insults to Gamble and Hoitz, and Martin and Hoitz get into a whisper-quiet, rolling-on-the floor fight, screened and surrounded by a phalanx of cops, who whisper rather than shout the usual testeronic encouragements. Even when Capt. Gene Mauch (Michael Keaton, using the name of the old Phillies/Twins/Angels manager) comes over and orders them to knock it off, he does it via whisper.

By this point, half an hour in, I’m thinking “The Other Guys” is the funniest movie I’ve seen in 10 years. Then the law of averages kick in.

Most comedies are uneven, possibly because most are spoofs, and spoofs invariably give in to, or buy into, the tropes of the very genre they’re spoofing. Happens here, too. The first part of the movie shows us the absurdity of action-hero cops, but the rest of the movie is about how the other guys, the guys like us, become the action-hero cops they always wanted to be. Hoitz gets into an epic, slow-mo gun battle in which he slides down a conference table on his back with both guns blazing, while Gamble, in his Prius, is great at high-speed chases. “Where did you learn to drive like that?” Hoitz asks. “’Grand Theft Auto!’” Gamble replies. The audience’s identification with these budding heroes is complete. They are us and heroes. Shame. Would that they had just stayed us.

Other tropes include Gamble and Hoitz 1) stumbling upon the true criminals, who are 2) high-powered investment types surrounded by men with guns, and then pursuing these bad guys despite 3) no support, and even interference, from gray-haired higher-ups in the police department. Not to mention the whole “opposites as partners” motif.

Wahlberg, whom I slammed 10 years ago, but who’s impressed in many movies since, plays a pretty good straight man. He even gets off a great line impugning another’s manhood: “The sound of your piss hitting the toilet sounds feminine!” he tells Gamble. Ferrell is hilarious as always.

There’s a lot of nice bits throughout: Gamble’s Little River Band (LRB) fixation; Captain Gene constantly, unknowingly, quoting TLC lyrics; the whole “Capt. Gene” thing, which Mauch says makes him sound like the creepy host of a kid’s show; Mauch’s open, friendly, unembarrassed face when they find him moonlighting at Bed, Bath & Beyond. Keaton brings something good here. He plays it low-key but funny. You see his early comedy chops on display again. Welcome back.

Has anyone written about the brilliant end-credits? A peripheral theme of the movie is ponzi schemes, and with early ’60-s-style animation we’re informed, while the credits roll, what they are, and how Bernie Madoff’s in 2008 makes the original in the 1920s seem like that of a piker. We’re shown just how much the $700 billion TARP bailout from 2008 was, and how the tax rate for the wealthiest has gone down over the last 30 years while the take-home pay of the wealthiest has skyrocketed. It’s fascinating, populist stuff that everyone should stay for. Bonus: post credits, there’s a final scene between Wahlberg and Ferrell.

When Patricia and I left the theater, we were preceded by two girls who were still laughing, uproariously, bodies bent over, about the closing-credits song, “Pimps Don’t Cry.” It’s a reference to Gamble’s back story: why he is who he is; why he’s a police accountant working a desk. Back in college, when the tuition went up, he basically became the pimp for a number of co-eds. He called himself “Gator” and acted the role. His dark side came out. That’s why he’s so timid in the present day; he doesn’t want to “set Gator loose.” To me, it was one of the weaker jokes of the film, but these two girls obviously disagreed.

For me, the funnier backstory is Hoitz’s. That, in fact, is the second of the two huge laughs I had during the movie. Hoitz is attending a group therapy session for officers who have discharged their weapons, and while the others relay their stories, bragging and high-fiving rather than tearily revealing tragic results, Hoitz sits quietly in a corner. The therapist then tries to get him to reveal his story but the others moan and bitch and don’t want to hear it. We soon find out why.

It was before Game 7 of the World Series and Hoitz was working security. He was in the long hallway before the locker room when a silhouetted figure approached. He told him to stop. The man didn’t. He repeated himself. He drew his weapon. He warned one more time. The man kept coming. So he fired and the figure fell out of the shadows and into the light: Derek Jeter wearing an iPod, now clutching his leg. “He shot Jeter!” one of the cops in the therapy session yells. “We lost the championship!” another shouts. Me, I laughed and laughed. Talk about wish fulfillment. I'm not proud of it, but I might have to buy “The Other Guys” for the sheer pleasure of watching, in slow-mo, Derek Jeter getting shot in the leg, again and again.

Tuesday August 17, 2010

Review: “Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS AND STUFF

Have I ever felt so old watching a movie?

“Scott Pilgrim vs. the World” does what it does well. It’s hip and irreverent and sometimes funny. It skewers Bollywood, sitcoms and video games. OK, so it’s more of an homage to video games. OK, so it is a video game. Video games allow dweeby guys to compete—and prosper—in rock ‘em, sock ‘em matches that involve levels and “health” and “life,” and “Scott Pilgrim” allows Scott Pilgrim (Michael Cera), a dweeby guy in Toronto, to compete and prosper in rock ‘em, sock ‘em battles to the death with the seven evil exes of his new maybe girlfriend, Ramona Flowers (Mary Elizabeth Winstead). Each evil ex is a different level and each level involves more points: 1,000 for taking out the first evil ex, 3,000 for the third, etc. And what happens when he reaches the final level? Epiphany. Of a sort.

The movie starts with all of Scott’s friends giving him shit for dating Knives Chau (Ellen Wong), a 17-year-old Chinese girl. (He’s 22.) Trouble is, Wong looks about the same age as Cera, and she’s twice as attractive, so it seems a step up. Thankfully, they have her act young so you can see their point. And it leads to this good bit of dialogue with Scott’s sister, Stacey (Anna Kendrick)

Stacey: A 17-year old Chinese schoolgirl? You’re serious?

Scott (abashed): It’s a Catholic girls school, too.

How to escape this dilemma? Scott dreams of another girl, Ramona, with dyed pink hair, then sees her the next day. She’s literally the girl of his dreams. The movie keeps doing this. A rock band literally blows the roof off the place, Scott literally gets a life. Is there a point to this or is it just a laugh?

How to escape this dilemma? Scott dreams of another girl, Ramona, with dyed pink hair, then sees her the next day. She’s literally the girl of his dreams. The movie keeps doing this. A rock band literally blows the roof off the place, Scott literally gets a life. Is there a point to this or is it just a laugh?

Scott’s pursuit of Ramona is clumsy, as such pursuits often are, but they work, as they often do in the movies. Then the trouble starts.

Scott plays bass for a garage punk band, Sex Bob-Omb, and in the middle of a battle of the bands, the first evil ex, Matthew Patel (Satya Bhabha), shows up, dressed in bizarre Bollywood crap, and they duke it out in comic-book, aerial, martial arts fashion. That Scott can do this causes no one to blink. Massive battles take place, enemies are literally pulverized, but there are no real consequences for the hero. Nothing is felt, you just get to the next level.

Most of the evil exes feel specific to this generation. We get a lesbian (from when Ramona was bi-curious), silent Japanese twins (male version), a skateboarder-turned-movie star, and a vegan/bassist. These last two are played by actors who have actually played superheroes: Chris Evans (the Human Torch/Captain America), and Brandon Routh (Superman).

The final evil ex, at level 7, is a more universal type: Gideon Gordon Graves (Jason Schwartzman), a slick record-company exec, who holds some kind of power over Ramona, and who actually defeats and kills Scott. Ah, but there’s that “life” he got at the previous level, which allows him to redo the fight with greater knowledge and understanding. It allows him to fight Gordon not for LOVE (which is apparently weak), but SELF-RESPECT (which is apparently strong).

Is that the great lesson of this generation? Before I saw the film I hoped that once Scott was victorious, as we knew he would be (the film can’t skewer that trope), he would decide that Ramona wasn’t worth it; that once he battled not only the ex-boyfriends but his fears he would be able to move on. The movie beat me to the punch but in a weak way, using a weak word like “self-respect.” Scott can’t move beyond fear because he never really has it. This is a gamer’s universe so there’s no fear because there are no consequences. There’s just embarrassment (with girls) and victory (in simulated battle).

I worked in games—four years at Xbox in the early 2000s—and I’m not much of a fan of that universe, which is without consequences and generally without sympathy. Look at the other characters here. They veer between the shrugging doofus (Comeau, who keeps showing up at parties) and the self-amused instigator (Scott’s gay roommate, Wallace, Kieran Culkin channeling Robert Downey, Jr.), without much in-between these two uncaring extremes.

Scott racks up the points. GOOD! COMBO! PERFECT! He wins. He gets the girl. But the victory is without consequences. And the girl remains unknowable.

Wednesday August 04, 2010

Review: “The Kids Are All Right” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The kids may be alright but the adults sure are screwed up.

One gets that feeling five minutes into the movie. The teenage boy, Laser (Josh Hutcherson), may hang out with a jerky friend, and the teenaged girl, Joni (Mia Wasikowska), may be too timid to move beyond Scrabble with the boy she likes, but at least there’s something open-ended and possible about their personalities. At least they don’t have 20 years of a relationship grinding and truncating each personality into a parody of itself. At least they didn’t name one of their kids ‘Laser.’

The couple in question is a lesbian couple but it may as well not be. Nic (Annette Bening) is the dominant, male figure who returns home from an important job (she’s a doctor), tosses off an exasperated line about the difficulty and importance of that job (“17 thyroids today”), then minimizes wifey’s contributions. She dotes on her baby girl, now 18. She acknowledges the girl is 18 but continues with the baby talk. She wears sleeveless T-shirts. She drinks too much.

The couple in question is a lesbian couple but it may as well not be. Nic (Annette Bening) is the dominant, male figure who returns home from an important job (she’s a doctor), tosses off an exasperated line about the difficulty and importance of that job (“17 thyroids today”), then minimizes wifey’s contributions. She dotes on her baby girl, now 18. She acknowledges the girl is 18 but continues with the baby talk. She wears sleeveless T-shirts. She drinks too much.

Jules (Julianne Moore) is the passive-aggressive, female figure who allows herself to be minimized, then resents that minimization. She wants to do something, start a landscaping business, but doesn’t know where to begin. To be honest, she’s afraid to start. Plus she gets no support in the matter. She’s a bit loopy in a west-coast way, and knows it, and resents it. During sex, she goes down on the dominant figure.

Is this an inevitability in relationships—that we grind each other into parodies of ourselves? I don’t know, but the beginning of the movie felt false to me in the way that first episodes of TV shows, where the characters are more broadly drawn than what they become, feel false. I would’ve appreciated a finer touch here.

Each of the two women gave birth to one child—Nic to Joni, Jules to Laser—and now that Joni’s 18, and at the urging of Laser, who is probably craving a male figure in his life, they search out the sperm donor, from back in ’92 or ’95, who was anonymous. Considering all of the messy possibilities they hit the jackpot. Paul (Mark Ruffalo) is a not-bad-looking, scruffy, laid-back dude who runs a restaurant using organic, locally-produced food. He rides a motorcycle. He exudes interest and passive sexuality.

The initial meeting between kids and donor is clumsy, as it should be, and Laser comes out of it disappointed, but Joni is jazzed and wants to see where it leads. Nic and Jules, of course, are horrified. Nic, the dominant figure in the household, is particularly upset that another bull is sniffing around outside, but she lets him in to diminish him. “Let’s just kill him with kindness and put it to bed,” she says. Except she’s the one who gets diminished. She can’t hold her wine and comes off as small and combative, while he comes off as mellow and reasonable. He gives Jules both encouragement for her landscaping business and her first job: fixing up his backyard. There, they bond over the word “fecund,” while she apologizes for all the double-takes because “I keep seeing my kids’ expressions in your face”—a fascinating area of inquiry that is all but forgotten when the two, more alike than not, fall into bed together.

At first it seems a one-shot. Then it happens again and again. Meanwhile, Paul is also bonding with both Joni, who gets to ride on the back of his motorcycle from the organic farm, and Laser, to whom he gives good advice about his jerky friend. Nic? Nic is working. She’s being nudged out of the picture.

The movie lost me when Paul gets serious about Jules. Yes, an argument can be made that while Paul’s personality is essentially unserious the kids have made him more serious, so now he’s ready to get serious. But I still didn’t buy it. I didn’t buy it particularly because at that point he was also sleeping with the most beautiful woman in the world, Tanya (Yaya DeCosta), the hostess of his place. DeCosta is a fine actress but it was tough believing that someone that beautiful even exists, let alone that she’s schtupping Mark Ruffalo, let alone that he then throws her over for Julianne Moore. (No offense to Julianne Moore.) For me, it was one “let alone” too many.

Tanya, by the way, gets off the best line in the movie, which is an early candidate for best line of the year. When Brooke (Rebecca Lawrence), the organic farmer, flirting with Paul with a basket of fruit, says “I thought you should have first taste,” Tanya, after Brooke leaves, mimics her, “I thought you should have first taste...” and then, in her own voice and under her breath, “...of my pussy.” I roared.

There’s been a lot of buzz this year from the filmfest circuit on “The Kids Are All Right,” and I liked it well enough but wasn’t blown away. It’s partly that broadly-drawn beginning. It’s partly the sense of privilege that permeates these characters in their busy, eating-outdoors lives. Back in the early 1990s, Steve Martin’s “L.A. Story” tried to be a kind of L.A. version of Woody Allen’s New York, but “Kids,” from writer-director Lisa Cholodenko (“Laurel Canyon”), pulls it off better than “Story” ever did—and that’s not wholly a compliment. Again, it’s the sense of privilege. These are people who have the time to be neurotic.

That said, Bening is a wonder and deserves another Oscar nomination, and possibly, finally, the statuette itself. Hutcherson sure has grown up fast (was “Bridge to Terabithia” really three and a half years ago?), while Wasikowska has something like true beauty about her.

The movie has buzz because of its unconventionality—a lesbian couple! looking their age!—but that unconventionality is wrapped in a conventional story and lesson. Family is hard but sacrosanct, and woe to he who violates that sanctity. Is the usual sanctity-of-marriage crowd objecting to this movie? Ironic if they are. It’s such a pro-family movie. In its quiet, forgiving end, in which the family is fortified against outsiders like Paul, I, identifying with Paul, the childless fortysomething, experienced regret at not knowing that feeling; at not having started my own family.

The kids are alright; the adults still need work.

Wednesday July 28, 2010

Review: “The Girl Who Played with Fire” (2010)

WARNING: SPÖILERS II

After everything she went through in “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” from subway attacks to rape, it’s a shame to see Lisbeth Salander (Noomi Rapace) get worse in “The Girl Who Played with Fire.” I don’t mean being shot and buried alive by her own father. I mean having to wear a New York Yankees sweatshirt and cap. Ick.

“Fire” starts out where “Tattoo” left off. Lisbeth is abroad, living in comfort by the peaceful sea, with the money she nicked from the bad guys. But she finds no peace. She has nightmares about her father, who abused her and her mother until she set him on fire when she was 12. That act resulted in incarceration in mental institutions, and a legal-guardian arrangement (specific to Sweden?) administered, first, by the sharp, sympathetic Holger Palmgren (Per Oscarsson), and then, when Holger suffered a stroke, by the horrific and misogynistic Nils Bjurman (Peter Andersson), who rapes Lisbeth in “Tattoo” but gets his: she sodomizes him with a dildo and tattoos on his fat white stomach: “I am a sadistic pig and a rapist.” It’s even longer in Swedish.

From her seaside villa, Lisbeth uses her computer hacking skills to track Bjurman and realizes: 1) he’s not submitting the necessary monthly reports on her that will keep the authorities off her dragon-tattooed back, and 2) he’s looking into tattoo removal. So she returns to Stockholm and confronts him at midnight with his own gun. Submit the reports, she tells him. And keep the tattoo.

From her seaside villa, Lisbeth uses her computer hacking skills to track Bjurman and realizes: 1) he’s not submitting the necessary monthly reports on her that will keep the authorities off her dragon-tattooed back, and 2) he’s looking into tattoo removal. So she returns to Stockholm and confronts him at midnight with his own gun. Submit the reports, she tells him. And keep the tattoo.

What she doesn’t know is that someone has already contacted him about her.

In the meantime, at Millennium magazine... Hey, what’s with Millennium anyway? It’s supposed to be one of the last bastions of a relevant print publication in an online world, yet the oldsters leading it, from our man Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist) to his lover, Erika Berger (Lena Endre), are super cautious about everything. They meet a kid, Dag Svensson (Hans Christian Thulin), who’s doing an investigative piece on human trafficking and prostitution in Sweden, and he has evidence that links many of these women to public officials, and he’s already done interviews with some of these public officials. Yet the Millennium staff only cautiously welcome him aboard for a two-month assignment? Grow a pair already.

At the same time, one wonders how much of an exclusive Dag actually has, since his girlfriend, Mia, has just published a treatise on the topic. We see the two planning to celebrate its publication by going on vacation. From my notes: “They look young and happy. They’re dead.”

Indeed. Two minutes later, Blomkvist finds them shot in their apartment. The weapon belongs to a lawyer, Nils Bjurman, and the only fingerprints belong to one Lisbeth Salander. When Bjurman is found dead, too, an APB goes out for Lisbeth’s arrest. Quaintly, and oddly for a computer hacker, Lisbeth first discovers this through a kind of “Wanted” poster stapled to a lightpost, then through print newspapers, and only lastly via something called the World Wide Web. It’s like we’re back in 1995.

By this point we’ve already been introduced to some of the bad guys, particularly a stoic, blonde brute named Ronald Niedermann (Micke Spreitz), who recalls the Russian villain in “From Russia With Love.” We see him fight Lisbeth’s sometime-lover, kickboxer Miriam Wu (Yasmine Garbi), as well as middleweight boxer Paulo Roberto (a real figure in Sweden, who plays himself), and Neidermann takes care of both handily. Despite their skills, their blows have no effect on him. Watching, I recalled a documentary about kids who suffer from the genetic defect analgesia, who literally feel no pain, (the doc is called “A Life without Pain,” and it is, no pun intended, painful and heartbreaking), and I wondered if that wasn’t Niedermann’s secret. It is. It's just not heartbreaking.

Meanwhile, Blomquvist has taken up where Dag left off, tracking down johns, but he’s doing it less for the article than to help clear Lisbeth. From one john he gets a name, Zala, and a story. Zala is a merciless, former top agent with the U.S.S.R. who defected to Sweden in the mid-1970s, and was thus protected by the Swedish national police and its intermediaries, including Nils Bjurman. Good start.

So what is our heroine, Lisbeth, doing while her friends are investigating for her and risking their lives for her? Not much. She's all third act, when she confronts Zala and his henchman, Niedermann, in a remote cabin. Zala, the man running the East European prostitution ring, turns out to be Alexander Zalachenko, who turns out to be, a la “Star Wars,” her father, who got played with fire, while Niedermann turns out to be her half-brother. In the end it's all about her.

Lisbeth is a stoic figure who keeps the world at a distance—one of the lessons she learns in “Fire,” in fact, is about letting people in (Blomqvist literally)—so Rapace doesn’t always have a lot to do acting-wise. But I love how alive her eyes become when she confronts her father. Does she enjoy seeing him? Or does she enjoy seeing him diminished? There’s a fierce intelligence in her. “I know you,” she seems to be thinking. “And you don’t scare me any more.”

He should. That night, father and half-brother lead her to a shallow grave. Blomqvist, we know, is making his way toward her and the remote cabin, and, used to the tropes of movies, we wonder when he’s going to arrive to rescue her. I’d clearly forgotten my heroines. Trying to escape, Lisbeth is shot twice by her father, dragged back by her half-brother, and buried alive. I’m on the edge of my seat. Where’s Blomqvist?

Cut to: Blomqvist, at dawn, looking at a map, his automobile pulled off to the side of the road. I nearly laughed out loud. Poor bastard.

Lisbeth isn’t just the girl with the dragon tattoo, or the one who played with fire, or the one who will kick the hornet’s nest in the next movie; she’s the girl who doesn’t need rescuing. She rescues. The movie conventions of 100 years are upended in her.

Thus, after being shot twice and buried alive, Lisbeth digs her way out using the cigarette case Miriam gave her at the beginning of the film, then takes an axe to her father’s head, then scares off Niedermann with her father’s gun. Which is when Blomqvist, the caring man, forever inconsequential in a fight, finally shows up.

Most of “Fire” disappointed me. The plot about the East European sex-slave trade is more-or-less forgotten, as are Lisbeth’s computer hacking skills, while there’s nothing nearly so engrossing as the mystery of the first film: the disappearance of Harriet Vanger and all of those girls. Here, we get no mystery. There’s a bad guy. His name is Zala. Hey, there he is! Worse, for most of the film we’re ahead of both Blomqvist (since we know about Nils Bjurman) and Lisbeth (since we find out about Niedermann’s analgesia). It’s not much fun waiting for your protagonists to catch up with you.

But my girlfriend loved the movie. When I asked why, she talked about how tough Lisbeth was, how calm she remained in battle, and how she wished she could be like her. Lisbeth is wish-fulfillment for women the way Bruce Willis is for men. I like that. I like having a female wish-fulfillment who doesn’t depend on a man, or a dress, or a pair of Manolo Blahniks.

Just lose the Yankees cap, Lisbeth. The Yankees are corporate and imperialist. You’re much more of a Pittsburgh Pirates girl.

Sunday July 18, 2010

Review: “Inception” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS (OR ARE THEY?)

“Dreams feel real while we’re in them,” says Cobb (Leonardo DiCaprio), early in Christopher Nolan’s “Inception.” “It’s only when we wake up that we realize something was actually strange.”

In this regard, nothing feels like a dream so much as a movie. In the dark we suspend disbelief. Then the lights go up, the analytic part of the brain starts working again, and we go, “Wait a minute.” Sometimes we don’t have to wait for the lights to go up.

That’s one of the things I loved about “Inception”: the parallels between its form (movies) and its content (dreams). At one point Cobb is attempting to recruit Adriadne (Ellen Page), his latest architect of dreamscapes, to become the final member of his team, his subconscious “Mission: Impossible” force, and they’re drinking coffee at an outdoor cafe in Paris when he tells her that dreams always begin in medias res; we don’t know how we got to a place, we’re just there. Then he asks her: “How did you get here?” She thinks, can’t remember, realizes they’re in a dream, but in the audience I’m thinking, “I know how she got there: the quick cut.” That is: They’re in one spot talking about a topic; then they’re in another spot a bit further in the same conversation. It’s a common storytelling device. We accept it in movies. Hell, we demand it of movies because we don’t want to watch characters walking downstairs, going outside, hailing a cab, being driven to the cafe, getting out, paying the cabbie, getting a table, ordering, drinking, and then continuing their conversation. Just give us the quick cut already. That’s part of why movies are the perfect medium for a story about dreams. Form lends itself to content.

My favorite of these parallels may be the moment Mal (Marion Cotillard), Cobb’s dead wife, who haunts his dreamscapes, and is in fact the most uncontrollable and malignant element within these dreamscapes (hence her name), tries to convince him to stay with her in his dream world. She tries to convince him that what he considers the real world? That’s the dream. Think about it, she says. Some faceless international corporation is out to get you—you think that’s real? As a movie audience, we accept that trope because we’ve seen it before: the subplot that continues to dog the protagonist throughout the plot, adding an extra frisson of tension. But once she mentions how absurd it is, well, it does seem absurd. Because it’s a movie, a Hollywood movie, and most Hollywood movies are absurd. She’s basically the movie critic in his subconscious, saying, “C’mon, man, this is bullshit.”

My favorite of these parallels may be the moment Mal (Marion Cotillard), Cobb’s dead wife, who haunts his dreamscapes, and is in fact the most uncontrollable and malignant element within these dreamscapes (hence her name), tries to convince him to stay with her in his dream world. She tries to convince him that what he considers the real world? That’s the dream. Think about it, she says. Some faceless international corporation is out to get you—you think that’s real? As a movie audience, we accept that trope because we’ve seen it before: the subplot that continues to dog the protagonist throughout the plot, adding an extra frisson of tension. But once she mentions how absurd it is, well, it does seem absurd. Because it’s a movie, a Hollywood movie, and most Hollywood movies are absurd. She’s basically the movie critic in his subconscious, saying, “C’mon, man, this is bullshit.”

So is this movie bullshit? When the lights come up, do we go, “Wait a minute”?

In “Inception,” Cobb is an on-the-lam extractor, a man who can navigate other people’s dreams and extract useful information for, say, international corporate rivals. That’s basically where we first see him. Like in a dream, we’re plopped in medias res into a complicated storyline and have to suss it out. Cobb, Arthur (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) and Nash (Lukas Haas), are trying to extract business secrets from international CEO Saito (Ken Watanabe). But their real selves are in a dingy room in a Latin American country in the midst of revolution, with IVs strapped to their arms putting them under. In the dream, an elegant party at Saito’s place in Japan, Cobb is betrayed by Mal, his dead wife, whom his unconscious keeps dragging along to gum up the works, but at last he has the information in hand when, no!, he’s forced to wake up because things are getting dangerous for their real selves. Except why the quick-cut to the Japanese kid on the train? We get the answer to that when Cobb and Saito fight in their dingy room and Cobb forces Saito’s face into an ugly shag carpeting. The room, it turns out, is the room where Saito often met his mistress, and he says he always hated that carpet, and the smell of it, and he can’t smell that smell now. So he knows he’s still in a dream. A dream within a dream. That revolution outside? That’s Saito’s subconscious, rebelling, like antibodies, and trying to attack the foreign substance, which is the dream’s architect, Nash. Their real selves are actually on the train, being administered to by the Japanese kid, who wakes the three team members with Edith Piaf’s song “Non, je ne regrette rien.” At first I thought this homage to Ms. Cotillard, who won an Oscar playing Piaf in “La vie en rose.” But it has a deeper meaning. This film is all about regret.

Saito quickly tracks them down. Not to hurt them but to hire them. And he wants something more dangerous that extraction. He wants inception: an idea planted into the mind of a rival, Robert Fisher, Jr. (Cillian Murphy), that will cause him to break up his international corporation, which currently controls one-half of the world’s energy. “Choose your team wisely,” he says to Cobb, in reference to Nash, who couldn’t make carpets smell right, who didn’t get the details right. He’s like the lackadaisical production designer on the Michael Mann set. Fired.

(At the same time, if you extend the metaphor, the real screw-up is the director, Cobb, whose guilt over the death of his wife is so strong he keeps dragging her along into other people’s dreamscapes. Is this a directorly admission that you’ll eff up the production when you bring your personal baggage onto the set?)

For his team, Cobb already has Arthur, his point man, and he quickly gathers the rest: Ariadne, who will design the dream, Yusef (Dileep Rao), who will administer the drugs, and Eames (Tom Hardy), the forger, who can impersonate important people from Fisher’s world in the dreamscape. It’s both a good team Cobb has assembled and a good team writer-director Christopher Nolan has assembled. Ellen Page is whip-smart. Cotillard is both dreamy-looking lost love and dangerous femme fatale. But I may have been most impressed with Hardy. He steals every scene. The scam is Cobb’s, the whole story is Cobb’s, and everyone seems to channel their energy into these, and his, obsessions; but Hardy suggests for Eames a life outside of this story. We don’t have much to wonder about with Cobb but we have everything to wonder about with Eames.

To plant their idea into Fisher Jr.’s mind, they plan on three levels of dreams, each one more dangerous, each one requiring a heavier level of sedation. They need time, too. On the plus side, each level you go down, time speeds up. Cobb and his wife once spent 50 years in a dreamscape together, growing old, creating their world, while in the real world, what, a month passed? Less? But they still need access to Fisher Jr. for an extended period of time without his knowledge. They get it when he books a 10-hour transatlantic flight to Los Angeles. So they book the rest of the seats. Everyone on board is with them. (Question: Has he no security, though? Does one control half the world’s energy and not travel with bodyguards?)

To reiterate, for myself as much as you: They enter his dream, his subconscious, but the dreamscape has been designed by Ariadne, and they, the team, are conscious actors, as opposed to figments of his subconscious like everyone else. But he can’t tell they’re conscious actors.

On the first level it’s raining hard, and they complain about the water Fisher drank on the plane. Nice touch. Then they kidnap him in a taxicab but things quickly go awry. A train, not designed by Ariadne, slams through the middle of a street, and suited toughs, projections, placed in Fisher’s subconscious to protect him from just this kind of attack, engage the team in a gunfight. Saito, along for the ride (for some reason), is shot in the chest, and the team holes up in a warehouse, where they are continually assaulted, and where Cobb tells them that dying in here won’t wake them up up there. They’re too heavily sedated to allow for such a wake-up jolt. So what happens? They will remain here, in Fisher’s subconscious, forever. Scary.

To get down to the next level, they get into a van with their IVs, and Yusef drugs them to sleep. Then he drives furiously through the dreamscape, chased by projections. That’s level 1.

At level 2, they’re at a 1940s-style hotel. At level 3, they’re at a wintry fortress that looks like something out of a James Bond movie or the ice planet Hoth. But every level affects the lower level. One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor. So if the van at level 1 careens wildly, the world of the 1940s-style hotel tilts correspondingly. This leads to some of the movie’s best visuals, particularly a fight in the hotel hallway that’s turning over and over, as the van, at level 1, rolls down a hill.

At level 3, both Fisher and Saito die, so Cobb decides to go into his own subconscious to retrieve them. Not quite sure how this works, to be honest. But Ariadne, who’s spent the movie sussing out the pieces of Cobb’s tragedy, goes along with him. To level 4.

Cobb is on the lam because he’s accused of murdering his wife. Apparently the two went deep into their 50-year-old dreamscape, grew old together, and she refused to come out. She refused to believe that their dreamworld was in fact a dream. So, for the first time ever, Cobb messed about with inception. He planted an idea directly into his wife’s mind that this world wasn’t real; that they needed to die, under train tracks, to get back to the real world. Which they did. All good. Except that idea followed Mal into the real world, and she became convinced that the real world wasn’t real, and that the two of them needed to kill themselves to “wake up.” And that’s what she does. She leaves evidence behind implicating him. That’s his tragedy. That’s why he’s on the lam and that’s why he can’t see his kids. Non, je regrette tout.

The dreamscape Cobb and Ariadne encounter at level 4 is the world, now crumbling majestically, that he and Mal created so long ago. There, with Ariadne helping guide him toward rationality, he finally faces his past, his regret, and the two retrieve Fisher and jolt him awake at level 3. Cobb then remains behind to retrieve Saito.

Thus, more or less concurrently, you have: Cobb confronting an ancient Saito at level 4; a gun battle at the ice fortress at level 3, where Fisher also confronts his father, and where the idea of breaking up his father’s empire is ingeniously implanted in Fisher’s mind; Arthur figuring out how to jolt the principles awake in what is now a gravity-less hotel at level 2; and it’s gravity-less because, at level 1, the van has been driven off a bridge and is falling in slow-motion into a river. Four cliff-hangers for the price of one. Four Steven Spielberg movies all at once. It’s like a Pixie-Stix IV straight into the veins of the summer moviegoer.

Eventually, at all levels, everyone is jolted awake, and everyone, including Cobb and Saito, wake up on the plane. Secret smiles are shared. Fisher looks like an idea, that most resilient parasite, has gotten hold of him.

Cobb is still wanted for murder in the U.S., of course, but Saito promised that if the mission succeeded he would make it all go away. And he does. At Customs, Cobb is allowed in. “Welcome back, Mr. Cobb.” His father-in-law (Michael Caine) is there to greet him, and he takes him back to their home, where his kids, who, throughout, have remained playful but distant, forever turning their faces away from him, finally turn, smile, and rush into his arms. It’s like a dream.

Is it? If you’re someone who enters dreamworlds all the time, one of the things you bring along, Cobb advises, is a totem: some small object that only you know about. Cobb’s totem is a small metal top, which, he suggests, never stops spinning in the dreamworld. That’s how he tests his reality, his sanity. If it stops spinning, he knows he’s in the real world. And just before his kids turn to him, he spins his totem on the dining room table, then forgets all about it as his kids rush into his arms. The camera doesn’t forget, though. It pans back. The top is still spinning. Still spinning. And just as it maybe begins to wobble, the screen goes dark. The End.

There’s going to be a lot of discussion on this lady-or-the-tiger ending, but the question I’d ask isn’t “Is the ending a dream?” but “Is this ending more effective?” I’d argue that it is. “Inception” is about questioning reality, and an ambiguous end lends itself to this theme, and we carry that feeling out of the theater. At least I did. As I walked in downtown Seattle at twilight on a Friday night, everything seemed slightly off. People seemed odder, buildings less substantial. And why were all these Japanese walking around speaking Japanese? Where was I anyway?

There are parallels, certainly, between “Inception” and “Shutter Island,” Leonardo DiCaprio’s previous movie that included a crazy wife who kills herself and the protagonist’s subsequent retreat from reality. But I felt “Inception” more. With “Shutter,” the craziness is isolated in one character. With “Inception,” it spreads. Like an idea. The sanest person in the movie, in fact, may be Mal, just before she kills herself. Once you navigate to the lower dream levels, who is to say that our level, the non-dream level, is the final level? Aren’t we told, all of our lives, that there is another, higher level? Or levels? Who’s to say that reality isn’t the dream from which we need to wake up? The greatest philosophers have said just that. Most of us have felt just that. Nolan is actually tapping into the sense of unreality that reality has.

Not bad for a summer blockbuster.

Friday July 16, 2010

Review: “Micmacs” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS AFFECTEE

If you felt Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “Amelie” (or, in the original French, “Le fabuleux destin d'Amélie Poulain”) was too pleased with its own quirkiness, then Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s “Micmacs” (or, in the original French, “Micmacs à tire-larigot”) is probably not the film for you.

Jeunet is a master visual storyteller. No argument there. In the first two minutes we see a mine-sweeper in the Sahara get blown up, his wife and son receiving the bad news, the wife catatonic at the funeral, the son taken away to Catholic school, the son punished at Catholic school, the son escaping from Catholic school—all with hardly a word spoken.

Then it’s 30 years later. The son, Bazil, is now Dany Boon, late of “Bienvenue chez les Ch'tis” (2008), the most popular film in French history. He’s working late at Matador Video, watching “The Big Sleep” dubbed in French, and repeating the dialogue along with Bogart and Bacall, or Bogart and Bacall’s French dubbers (who, by the way, are fantastique), when he hears gunfire, real gunfire, outside. He goes to the door and sees men in a car chasing a man on a motorcycle—or vice versa. There’s a crash, a gun goes off accidentally, and the bullet goes, pow!, straight into Bazil’s forehead. Down he goes. Out come the opening credits.