Movie Reviews - 2010 posts

Thursday December 30, 2010

Review: “Rabbit Hole” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

How do you deal with an unbearable tragedy, the death of a son, a four-year-old son, who chased his dog into the street and got hit by a car? If you’re his parents, how do you go on?

In “Rabbit Hole,” Becca and Howie (Nicole Kidman and Aaron Eckhart) come up with opposite answers. She excludes, he includes. She removes, he embraces. In Biblical terms, she commits sins of omission, he commits sins of commission. But “sin” is too strong a word for what they’re doing. They’re just trying to find comfort. They’re both just trying to keep living.

As the movie opens she’s putting fresh soil into her garden. It’s the soil to which we all return, and to which her four-year-old son, Davey, returned, too early, eight months previous, but here, for a moment, it feels like a positive. It’s soil to grow, not bury. Then her neighbor shows up and invites Becca and Howie to dinner that evening. Becca politely declines. Plans, she says. But they have no plans. She just can’t be with people. She’s still in the act of burying.

As the movie opens she’s putting fresh soil into her garden. It’s the soil to which we all return, and to which her four-year-old son, Davey, returned, too early, eight months previous, but here, for a moment, it feels like a positive. It’s soil to grow, not bury. Then her neighbor shows up and invites Becca and Howie to dinner that evening. Becca politely declines. Plans, she says. But they have no plans. She just can’t be with people. She’s still in the act of burying.

She’s slowly divesting herself of everything that reminds her of the pain of her son. She starts with the dog that the boy chased into the street (now cooped up at her mother’s apartment), then the drawings on the refrigerator (put into boxes in the basement), then the clothes in the bedroom (given to Goodwill). Eventually she’ll suggest selling the house itself.

Her husband’s the opposite. He watches the same video of his son, over and over again, on his iPhone. He takes comfort in what’s still here. Until one day the video isn’t. After she uses his phone. Oops.

At group therapy, she can’t abide the way other couples assume an order to the universe. How the death of their child was part of God’s plan. How God needed another angel in Heaven. “Then why didn’t He just make one!” Becca finally erupts. “He’s God!” Everyone stares, aghast. So much for group.

She keeps doing this. She holds in, then erupts. A child in a grocery cart pesters his mother for fruit rollups and Becca confronts the mother, tells her to give in, says it won’t hurt him. The mother reacts as mothers do. She says mind your own business. She says, “Do you have any children? I didn’t think so.” Now it’s Becca’s turn to be aghast and she slaps the woman in the face. Basically she commits a criminal act. When she runs off, horrified by what she’s done, by what she’s become, her sister, Izzy (Tammy Blanchard), tries to explain to the mother about how Becca lost a child, etc., but the mother isn’t having it. “I don’t care!” she says.

Neither do we, by this point. That’s the problem. The film juxtaposes two ways of dealing with grief but one of them—Becca’s—is solipsistic and unsympathetic. Howie tries to take comfort in intimacy, in his wife, but she refuses to let herself feel good and makes accusations. “You want to rope me into having sex?” she says, horrified. Later when he brings up having another child, this becomes the accusation. “Were you trying to get me pregnant?” she says, horrified. Howie, on the other hand, never loses our sympathy. For a time, left out in the cold with Becca, he contemplates an affair with another, warmer woman (Sandra Oh), but he doesn’t go through with it. “I love my wife,” he finally says. He’s just waiting for her to return.

Instead of getting close to her husband, though, Becca begins an odd relationship with the high school boy, Jason (Miles Teller), who drove the car that killed her son. She follows his school bus. She follows him to the library. They begin to talk on park benches. Is this a sex thing, one wonders, Kidman’s “Birth” revisited, or a maternal thing? Teller’s got a great face, sad and dumpy, with a puffiness around his eyes as if he’d just woken up or never been to sleep. He’s obviously devastated by what’s happened. He’s also been working on a comic book, “Rabbit Hole,” about parallel universes, about all of the other lives we might be living instead of this one. She reads the book he read for research. She reads his comic book. And in the end it’s this notion—that somewhere, in the many somewheres out there, her son is still living—that finally gives her comfort. She’s saved, not by God and religion, but by scientific theory.

“Rabbit Hole” was directed by John Cameron Mitchell (“Hedwig and the Angry Inch”) from a screenplay by David Lindsay-Abaire, who adapted his own Pulitzer-Prize-winning play, and there are moments that feel a bit theatrical. The best speech in the movie, in fact, delivered by Becca’s mother, Nat (Dianne Wiest), feels theatrical to me. I get a glimmer of the artificiality of the stage from it. But I wouldn’t change a word.

Throughout the movie, the main source of tension between Nat and Becca is that Nat, in an attempt to console her daughter, keeps bringing up the fact that she, too, lost a son. Becca’s not having it. Her brother died at 30, not 4, and his death was self-inflicted (a drug overdose), he didn’t get hit by a car. But there’s still pain there. Late in the movie, heading into the basement with her mother, Becca comes across Davey’s things, his refrigerator drawings that she’d hidden earlier in the film, and it’s like a punch in the gut. “Does it go away?” she suddenly asks. “What?” Nat asks. “The feeling,” Becca says. “No,” Nat says. There’s a pause. “It changes, though.” When asked how she says this:

The weight of it, I guess. At some point it becomes bearable. It turns into something you can crawl out from under. And carry around—like a brick in your pocket. And you forget it every once in a while, but then you reach in for whatever reason and there it is: “Oh right. That.” Which can be awful. But not all the time. Sometimes it’s kinda... Not that you like it exactly. But it’s what you have instead of your son.

For all the issues I have with the movie, I know I’ll carry these words around with me—and not like a brick—the rest of my life.

Tuesday December 21, 2010

Review: “Black Swan” (2010)

WARNING: WHITE SPOILERS, BLACK SPOILERS

At the least, particularly for those of us unfamiliar with ballet, we have a new metaphor with which to talk about ourselves. After the movie, the group of us, six in all, grabbed a bite and talked about whether we thought we were more white swan or black swan. Vinny claimed black swan for himself but no one agreed. (The man can demonstrate how to fold a fitted sheet, for God’s sake.) Theresa is obviously black swan, while Laura, who danced ballet until she was in her late teens, is decidedly mixed. Patricia, my Patricia, loves hanging with the black swans—like Ward—to bring out the black swan in herself. Because she’s mostly white swan.

Me? I am so white swan it hurts. I began this blog, in fact, with the same hope that ballet director Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel) has for his new star, Nina Sayers (Natalie Portman), as she prepares for “Swan Lake”: to give up some part of the careful, controlled half (the white swan part) and let go into wildness and creativity (the black swan part). She had better luck than me but at a steeper price. The white swan is a bitch of a muse.

Has any recent movie gotten us into the head of its main character as well as this one? I kept having to take deep breaths after it was over. I’d been holding my breath for the last half hour along with Nina.

Has any recent movie gotten us into the head of its main character as well as this one? I kept having to take deep breaths after it was over. I’d been holding my breath for the last half hour along with Nina.

It helps to think of the white-swan part of Nina’s personality as less about innocence than control. Sure, Nina is sexually innocent, but one suspects it’s a direct result of her control and discipline. I mean, she doesn’t think about touching herself until Leroy suggests it? Until it might help get the part she covets? I’ll masturbate, but only to be good in the role. One way to make students do their homework.

No, Nina is hardly innocent. She’s covetous. Early in the film, after Beth Macintyre (Winona Ryder) trashes her own dressing room when she learns she’s been summarily dismissed as prima ballerina of their New York ballet company, Nina sneaks in and sits at the vanity mirror and looks at herself and tries out Beth’s lipstick; then she pockets Beth’s lipstick. It seems a minor thing. Until later in the film when Beth is in the hospital and Nina brings out all the things, including diamond earrings, that Nina has stolen from her over the years. She keeps dipping into her pockets and coming out with more stuff. She’s been coveting the role of prima ballerina for years, and now it’s hers, but she can only see little versions of herself ready to take what’s hers. She assumes the world is like her—we all do—and that’s why she’s paranoid. She knows how awful the desire to take.

The rival she’s most fearful of is Lily (Mila Kunis), late of a San Francisco company, whom she first sees riding the subway and getting off a stop too early and thus arriving late for rehearsal. Lily’s all black swan. Does she need to warm up? “I’m good,” she says. She has a beautiful tattoo of black wings on her back. Nina’s back is full of scars and a rash from where she scratches herself at night. Lily talks boldly, walks with a swagger, while Nina tiptoes and speaks in a squeak of a voice. She’s all apologies. “I’m sorry,” she tells Leroy. “No! Stop saying that!” he responds.

Leroy plays the girls off each other like a movie director. He exacerbates the tensions. He leaves everyone dangling. “Would you fuck that girl?” Leroy asks others about Nina, within earshot of Nina, implying no. He kisses her in private, forcing her mouth open until she responds, then breaks it off. “That was me seducing you when I need it to be the other way around,” he says.

But Leroy is messing with forces that have been built up over a lifetime. Nina still lives with her mother, Erica (Barbara Hershey), in a cramped New York apartment, and her bedroom is all fluffy whites and pinks, with stuffed animals and ballerina music boxes playing tinkly music. She’s isolated, at home and at the company, and lives too much in her head. “The only person standing in your way is you,” Leroy tells her. Leroy wants Nina to unleash something, but what she unleashes is darker and more self-destructive than he imagines. She sees doppelgangers everywhere. IMDb.com lists both Portman and Kunis as 5’ 3”, Ryder a half-inch taller, and each is dark-haired and pretty. So who’s that coming towards her? Is that Beth, whom she replaced, or Lily, who wants to replace her as surely as she wanted to replace Beth? Or is it some darker version of herself—the black swan demanding freedom from the tight grip of the white swan? Or is it her mother? There’s creepy women stuff throughout the film. “You girls are nuts,” I told Patricia afterwards.

Three things propel the story along: 1) We want to know if Nina dances the part; 2) we want to know if she dances it well (if her black swan is released); 3) and we want to know, finally know, what’s real. We assume, for example, when Lily returns to Nina’s place after a night of carousing, and the mother doesn’t comment upon her presence, that, yes, Lily’s not really there, that she’s just in Nina’s head. So much of the movie is a guessing game. OK, this probably isn’t really happening. She really isn’t pulling the skin off her finger, her toes really aren’t stuck together, the old man in the subway really isn’t rubbing his crotch. Is Lily really in her dressing room? Did she really kill her? Is there someone else bleeding to death in the shower stall? Getting into the heads of characters is the novel’s business but no one does it better with film than director Darren Aronofsky.

The ballet numbers are beautifully filmed, the black swan dance a highlight. But did I need that ending? It parallels the ballet, certainly, as well as Aronofsky’s previous film, “The Wrestler,” but without the poignancy. Randy the Ram reaches a dead end, he feels useless, that’s why he does what he does. But Nina is at the top of her game so her on-stage suicide merely feels self-destructive. And does it muddy the metaphor or sharpen it? It’s the white swan who demands perfection ... and so she stabs herself to release her black swan ... in order to be perfect? Am I missing something? I need to think on it some more.

At the least, Nina is the latest character to personify St. Therese’s maxim. Her prayers are answered and the tears flow.

Sunday December 19, 2010

Review: “The Fighter” (2010)

WARNING: ROCKY SPOILERS

According to IMDb.com, there have been 12 movies from various countries called “The Fighter.” David O. Russell’s, starring Mark Wahlberg and Christian Bale, is the lucky thirteenth.

The story may seem familiar. It’s about an underdog boxer, a gentle man from a working class neighborhood, who wastes his talent for most of his youth, and then, on the other side of 30, takes one last shot at proving he weren’t just another bum from the neighborhood, and finally, finally triumphs, with his trainer in his corner and his best girl by his side.

We can be forgiven for asking: OK, so how does it differ?

For one, “The Fighter” has the advantage of being mostly true.

It has the added advantage of Christian Bale’s over-the-top, look-at-me-I’m-not-Batman performance as Dicky Eklund, a one-time middleweight contender, trainer to his half-brother, Mickey Ward (Mark Wahlberg), and crack addict.

It has the added advantage of Christian Bale’s over-the-top, look-at-me-I’m-not-Batman performance as Dicky Eklund, a one-time middleweight contender, trainer to his half-brother, Mickey Ward (Mark Wahlberg), and crack addict.

In ’78 Eklund went the distance against Sugar Ray Leonard but lost by unanimous decision. He also knocked down the champ in the 8th round. Eklund’s been living off that moment ever since. He’s “the Pride of Lowell,” never at a loss for words, and, as the movie opens, an HBO camera crew is following around the brothers. We assume it’s pre-fight hype, since Mickey’s about to step in the ring again despite three straight losses, but the crew is actually following around Dicky. He crows about how they’re filming his comeback, but one look at his emaciated body and you wonder, “What comeback?” Yet there’s the camera crew again. A third of the way through the movie, we get our answer. A local at a bar asks a member of the crew what the movie’s about, and the guy replies, “I told you. It’s about crack addiction.” That line lands like a body blow. Dicky’s self-delusions, and his family’s delusions about him, are laid open in the matter-of-factness of the response. What else could it be about?

The HBO doc is, in fact, a turning point of the movie. It’s the moment Mickey comes to his senses about Dicky, Dicky half comes to his senses about himself, and the family’s eyes, at least momentarily, are opened. For a second I condemned this family, the awful mother, Alice (an incredible Melissa Leo), and those harpyish sisters, for needing HBO to show them how their son/brother lives. A second later I realized we all need such docs about our loved ones. My older brother is an alcoholic, about which he and I have no delusions, but I don’t know how he spends his days. The people closest to us are still unknowable.

When the HBO doc airs, Dicky’s in prison, on too many counts to mention, but he hasn’t lost his swagger. As they’re about to air the doc, he revels in the attention and applause the other inmates give him. “Going to Hollywood!” he says. He thinks it’s going to be fun. He’s forgotten what he’s said. He doesn’t know who he is.

Out in the world, Dicky is full of lies and bonhomie but in the doc he speaks the truth. “You feel young, like everything’s in front of you,” he says of smoking crack. “Then it fades and you have to get high again.” There is no comeback. The comeback is in the crackpipe.

Up to this point, Dicky has not only been a lousy brother and son, he’s been a lousy trainer, too. Mickey is forced to wait for him at the gym; he’s forced to wait for him with the limo that’ll take them to the airport, and then to Vegas, to fight another welterweight. But in Vegas Mickey is told his opponent has come down with the flu and the replacement is a middleweight, a guy with 20 pounds on him. He fights him anyway and gets his face smashed in. Back in Lowell, he and his soon-to-be-girlfriend, Charlene (Amy Adams), are talking:

Mickey: Everybody said I could beat him.

Charlene: Who’s everybody?

Mickey: My mother and my brother.

(Earlier they’d had a bit of dialogue as spare as anything by David Mamet. Mickey has two bandages on his face and Charlene tells him, “Your thing’s coming off.” He reaches for the bandage above his right eye and she says, “Your other thing.”)

Mickey should be the pampered center of attention—as any contender is—but his needs are overshadowed by his brother’s, who sucks the air out of any room he swaggers or stumbles into. Everyone warns Mickey he needs to cut his brother loose or miss his shot, and, after the HBO doc, he takes their advice. A local cop and trainer, Mickey O’Keefe (playing himself), begins to train him, with money from a local businessman. The mother has a fit, and flies at her son and Charlene, with claws bared and tongue wagging, her awful daughters tagging along. A fight breaks out among the women. A catfight? Not close. There’s nothing sexy about it. Family is no support here. The mother, like Dicky, thinks she’s the center of the story when Mickey’s the one in the ring. Much of the movie is spent waiting for Mickey to realize this, to articulate this, himself.

Once he breaks free from his family, once he has the money to train year round, he begins to win, but the movie knows this isn’t the whole answer. Mickey’s been called a “stepping stone,” the guy other guys use to get their shot, and before a big match with Alfonso Sanchez, an undefeated contender with a title shot, Mickey visits Dicky in prison and is asked about his fight strategy. In the audience we’re thinking, “Don’t tell him,” but Mickey tells him and Dicky finds fault and offers an alternative. In the audience we’re thinking, “Don’t listen, get out, don’t let him drag you down again,” but it turns out Mickey’s original fight strategy got him nowhere. It’s Dicky’s, adopted late in the match, that wins the match. Now it’s Mickey with a title shot.

First, more family drama. It’s not enough to break free of family—as nice as that sounds—because you’re never truly free of family. So conflicts have to be resolved. People have to be reconciled. Out of prison, back in the gym, and back in the ring with his brother, Dicky has scattered Mickey’s supporters—Mickey O’Keefe, Charlene—and left him with his mother and sisters, who talk up Dicky yet again, who confuse the movie yet again, and it’s Mickey’s Popeye moment. All he can stands, he can’t stands no more. Thus: body blow, body blow, Dicky goes down. Mickey finally finds his voice. He confronts his mother, his sisters, his brother. He basically says, as we all need to say, “This is my movie!”

For something so messy for so long, it gets neat quickly. Kudos to the filmmakers for making it seem plausible that within five minutes of screentime: 1) Mickey finds his voice; 2) Dicky gives up crack and rallies his brother’s original supporters; and 3) Mother and sisters accept their subordinate status. And we’re set up for our finale and the title shot.

The Fighter” is a good movie, a worthy movie, but not a great movie. Wahlberg is fine, but he’s playing his gentle-voiced, blending-into-the-background leading man again. (See: “Planet of the Apes,” “The Truth About Charlie,” “The Italian Job.”) He’s a bit dull. In this way, the movie parallels its own story. Just as Dicky overshadows Mickey, so Bale’s performance overshadows Wahlberg’s. I’m not sure if this is ultimately a strength or a weakness, but I wish Wahlberg’s characters had as much in them as Wahlberg seems to.

But what is a weakness of the movie? That original “Rocky”-like synopsis. The basic story of “The Fighter” is the most oft-told story in Hollywood history: the underdog triumphs. It’s what we want while sitting in the audience but it’s also why the movie doesn’t resonate much afterwards. Mickey wins! That’s nice. This is what it takes to win! That’s nice. This is a story of two fighters, two brothers, Mickey and Dicky, who both triumph over their personal demons! That’s nice. And it ends. And it’s complete. And we’re happy.

That’s what makes great entertainment. But that’s not what makes great art.

I compare “The Fighter” inevitably, and unfairly, to Darren Aronofsky’s “The Wrestler,” which is a movie about an entertainment (professional wrestling) rather than an art (boxing), yet is, itself, closer to art than entertainment. Because it finds a different way out. Its title character, Randy the Ram (Mickey Rourke), is on the wrong end of his 40s, reaches a dead end and sees no alternatives, so his return to the ring, and impassioned speech in that ring—a triumph in the trailer—is actually a suicide. That’s the unique and horrifying way out. In the final shot we see Randy soaring off the turnbuckle and out of the picture and out of, one assumes, life, but we have to fill in the end ourselves. Maybe that’s why that movie keeps resonating. We have to assume its ending as much as we have to assume our own.

Thursday December 16, 2010

Review: “Please Give” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I met Nicole Holofcener briefly on the set of HBO’s “Six Feet Under” in 2004. I was visiting a friend there, a writer/story editor for the show, and she was directing an episode he had written, and after introductions I told her how much I liked her movie “Lovely & Amazing.” She quickly dismissed the compliment. Because most compliments are bullshit? Because inuring yourself to compliments is part of inuring yourself to criticism? I got the feeling she thought that no one had actually seen the movie. This was in the days before I seriously looked at box-office numbers and so I had that warped perspective that my milieu was the milieu. To me, “Lovely & Amazing” wasn’t a film with a limited release of 175 theaters around the U.S. It was a film that showed up in Seattle and never went away. Everyone talked about it.

It’s a shame we had this disconnect before I could compliment her on the film’s opening scene. Remember? Michelle Marks (Catherine Keener) is trying to sell her homemade trinkets to a trinket store and she runs into a former classmate, who seems cool and collected, and she asks what she’s been doing. “I’m a doctor,” the woman says. Michelle thinks the woman is joking and laughs. How could someone be a doctor already? “We’re 36,” the woman says. It’s a brutal scene with which I wholly identified. Peers become professionals, they become parents and adults, and you’re left behind trying to sell crappy gimcracks at some crappy gimcrack store. Life, somehow, has passed you by.

It’s a shame we had this disconnect before I could compliment her on the film’s opening scene. Remember? Michelle Marks (Catherine Keener) is trying to sell her homemade trinkets to a trinket store and she runs into a former classmate, who seems cool and collected, and she asks what she’s been doing. “I’m a doctor,” the woman says. Michelle thinks the woman is joking and laughs. How could someone be a doctor already? “We’re 36,” the woman says. It’s a brutal scene with which I wholly identified. Peers become professionals, they become parents and adults, and you’re left behind trying to sell crappy gimcracks at some crappy gimcrack store. Life, somehow, has passed you by.

I never saw “Friends with Money,” Holofcener’s 2006 film about this same subject—the divide between friends with success/money and those without—possibly because the reviews were so-so. I wanted to see “Please Give” in the theaters this spring (widest release: 272 theaters) but time slipped away. Plus it looked, you know, a little precious: a slice-of-life about the vague wants and distractions of solipsistic New Yorkers. But lately it’s been landing on some top 10 lists so I decided to check it out.

And?

It’s a little precious: a slice-of-life about the vague wants and distractions of solipsistic New Yorkers.

Kate and Alex (Catherine Keener and Oliver Platt) run a mid-century vintage furniture store for people with more money than sense: a table for $5,000, bookcases for $1,400 apiece. Kate acquires these pieces by visiting the homes and condos of the recently deceased and paying off relatives who don’t know the true value (or the true inflated value) of the furniture; who just want it all gone. It’s a ghoulish gig. There’s a sense of waiting for people to die in order to live. Kate and Alex are also waiting for their 91-year-old-neighbor, Andra (Ann Morgan Guilbert), to die, so they can combine her condo with their own and make something bigger and better.

Alex is fine with all of this. He’s an unremarkable middle-aged man who listens to Howard Stern and never reads any more—even magazines—but Kate feels increasingly guilty. She feels she’s taking advantage of people. Her guilt manifests itself in giving money—$5 here, $20 there—to panhandlers. At one point she even gives a doggy bag to a black man on the street but he’s simply waiting for a table at a crowded restaurant. Apologies ensue. She exudes the need to be forgiven. Her attempts at volunteering for the less fortunate are equally inept. She pities them. An elderly woman is stooped from rheumatoid arthritis. “Is it painful?” she says. “It looks very painful.” She tries to help kids with learning disabilities but feels so sorry for them she begins to cry. “You have to leave now,” the director of the facility tells her. It’s the best part of the movie.

Their counterparts in the solicitude/stoicism dichotomy are Andra’s granddaughters: Rebecca (Rebecca Hall), a passive mammogram technician, who cares too much about Grandma, and Mary (Amanda Peet), an overly tanned spa technician, who cares too little, and who begins an affair—surely one of the more unlikely affairs in movies—with dumpy ol’ Alex. He’s attracted to her, she’s bored. They bond over Howard Stern.

We get some good bits with Grandma—“You gained weight!” she tells Alex, bluntly, in the manner of the aged—but Holofcener also reminds us of the unbearable sadness of aging: losing your mobility, your sight, the world shrinking until your one solace are the idiot rhythms of “Entertainment Tonight.” George Clooney is an actor who has it all... This stuff is in the background of her place all the time, and there’s a kind of horror to it. That awful, chummy language about people we don’t know. When she dies, it’s one of the six sentences spoken at her funeral: “She liked watching ‘Entertainment Tonight.’”

In this manner, “Please Give” touches on important themes but then leaves them alone. It’s a slice of life that still manages to feel artificial. Plus there’s nothing driving the story. All of these New Yorkers are as passive as Seattleites. They all feel peripheral.

Let’s ask the dramatist’s question: What do the characters want? Kate and Alex want people to die, and for this Kate wants to be forgiven. Rebecca wants a boyfriend, and winds up with one, but overall she’s not quite there. Who is she? I have no clue. Mary thinks of herself as a straight talker, but her obsession with a clothing clerk turns out, in the final act, to be a pathetic version of stalking. Meanwhile, Kate and Alex’s 15-year-old daughter, Abby (Sarah Steele, in a fine performance), wants a $200 pair of jeans. She’s the most clearly defined character in the film.

Sunday December 05, 2010

Review: “Fair Game” (2010)

WARNING: The British Government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of SPOILERS from Africa.

We like being lied to. That’s the problem.

We like the lies of Hollywood in particular. We like believing we are good, and others are bad, and we stare them down and shoot them down and ride off into the sunset. We like this narrative so much we’ve transferred it into the real world, which is complex and problematic, then we’re surprised when the narrative falls apart. Or do we simply ignore it when it falls apart? We move on to other narratives, other lies, and keep digging ourselves in deeper. It’s like our national debt but with lies. We tell one lie to make up for another to make up for another. Soon we’re steeped in it. We’re a sick country, a sick race. Are we tired of it yet? Do we want to know what’s true anymore?

“Fair Game” is a movie about a series of lies perpetrated by the Bush administration, sometimes on itself, and certainly on us, from 2002 to 2005. They were lies with massive consequences, lies that got us into war, lies that led to the deaths of tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, maybe someone you knew. Maybe someone close to you is now dead because of what the Bush administration wanted to believe. They reconfigured the globe because of what they wanted to believe. The one time they told the truth, it was a treasonous act. But they got away with that, too, because they lied their way out of it.

“Fair Game” is a movie about a series of lies perpetrated by the Bush administration, sometimes on itself, and certainly on us, from 2002 to 2005. They were lies with massive consequences, lies that got us into war, lies that led to the deaths of tens of thousands, maybe hundreds of thousands, maybe someone you knew. Maybe someone close to you is now dead because of what the Bush administration wanted to believe. They reconfigured the globe because of what they wanted to believe. The one time they told the truth, it was a treasonous act. But they got away with that, too, because they lied their way out of it.

My god. Can we be incensed again? Is that still possible? Let’s run through it.

We got into a war because of lies.

When a man called us on one of those lies, we lied about him. We tried to ruin his life.

When that wasn’t enough, we told the truth about his wife. She was a CIA agent and we outed her. We cast her aside. She was a good soldier, and “Support the Troops” signs were everywhere back then, but her husband was pointing out the lies in the war narrative so she had to be sacrificed to make the Joe-Wilson-is-incompetent narrative work. She was, as Karl Rove later said, fair game. To Karl Rove, we're all fair game.

The movie should work. It should work the way that “All the President’s Men” works and “The Insider” works. Two people, attempting to uncover the truth, take on a vast, powerful entity intent on continuing the lie. It’s a classic underdog narrative, the kind Hollywood loves producing. And it’s true.

But it doesn’t quite work here, does it? “Fair Game” is a good movie, a necessary movie, a movie you want more people to watch. But Doug Liman doesn’t make it sing the way Alan J. Pakula made “All the President’s Men” sing and the way Michael Mann made “The Insider” sing. Why?

Is it because he shows us some of the inner workings of the Bush White House? Was that a mistake? Pakula never got us into the Nixon White House and Mann only showed us a snippet of a conversation between Brown & Williamson’s CEO and his lawyers—a snippet, it can be argued, that Jeff Wigand (Russell Crowe) could hear as he stormed out of the CEO’s office. Isn’t it better to keep the enemy at a distance? Shadowy? Unseen? Wasn’t that the lesson of “Jaws”?

Or is the problem that, of the two heroes in “Fair Game,” neither is a reporter? Both heroes in “President’s Men” were reporters: Watergate was a mystery and they were trying to uncover the truth. One of the heroes of “The Insider” was a reporter, and he was trying to get a former tobacco company vice-president, Wigand, and then his network, CBS, to reveal the truth. In “Fair Game,” we’re down to zero. The reporters in this movie don’t uncover the truth, they help cover it up. They have high-ranking government sources who feed them information, or disinformation, which they then spread. They provide obfuscation rather than clarity. They ambush the hero outside his house. “Isn’t it true...?” “What about the allegations that...?” They’re part of the problem.

No, the heroes in “Fair Game” are a career diplomat, Joe Wilson (Sean Penn), and his wife, an undercover CIA operative, Valerie Plame (Naomi Watts). For most of the movie, they’re working on different aspects of the post-9/11 world. She’s trying to find the bad guys in the Middle East and he’s sent to Niger to see if one Middle East ruler, Saddam Hussein, bought, or tried to buy, yellowcake uranium there. He concludes no, the administration concludes otherwise, and Pres. Bush, in his January 2003 State of the Union speech, says the 16 words that provide a justification for war:

The British Government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.

Initially Wilson concludes he’s referring to another country in Africa. He assumes they have other information. But after the war, in a New York Times Op-Ed, he comes out with what he knows.

It’s startling reading that Op-Ed, “What I Didn’t Find in Africa,” now, more than seven years later. Its language is so mild. It’s so straightforward. Wilson writes:

If my information was deemed inaccurate, I understand (though I would be very interested to know why). If, however, the information was ignored because it did not fit certain preconceptions about Iraq, then a legitimate argument can be made that we went to war under false pretenses. (It's worth remembering that in his March ''Meet the Press'' appearance, Mr. Cheney said that Saddam Hussein was ''trying once again to produce nuclear weapons.'') At a minimum, Congress, which authorized the use of military force at the president's behest, should want to know if the assertions about Iraq were warranted.

Wilson’s Op-Ed was published on Sunday, July 6, 2003. A day later the White House admitted its “WMD error.” A week after that, Robert Novak came out with his column, “Mission to Niger,” in which Joseph Wilson’s wife, Valerie Plame, was outed as a CIA agent.

Despite the outing, Novak’s column is fairly tame, too. He even owns up to Wilson’s exemplary background:

His first public notice had come in 1991 after 15 years as a Foreign Service officer when, as U.S. charge in Baghdad, he risked his life to shelter in the embassy some 800 Americans from Saddam Hussein's wrath. My partner Rowland Evans reported from the Iraqi capital in our column that Wilson showed “the stuff of heroism.” The next year, President George H.W. Bush named him ambassador to Gabon, and President Bill Clinton put him in charge of African affairs at the National Security Council until his retirement in 1998.

But Novak is also sloppy. His second paragraph begins this way:

Wilson's report that an Iraqi purchase of uranium yellowcake from Niger was highly unlikely was regarded by the CIA as less than definitive...

By the CIA? Or by certain officials within the CIA? The question was never whether Wilson’s account was definitive or viewed as definitive; the question was, and remains, why the Bush administration believed Report B over Report A.

In the movie, Wilson’s Op-Ed leads to a discussion between Scooter Libby and Karl Rove, in which the former says, “We need to change the story,” and the latter says, ominously, “Who is Joe Wilson?” For the rest of the movie, they create their own Joe Wilson in the press. Misinformation is spread. The truth struggles to get out.

After Novak’s column is published, Plame scrambles to protect her operatives. “I have 819 teams in the field,” she says. “It’s over,” she’s told. Then she clams up. She plays the good soldier. There’s a scene where she and CIA director George Tenet (Bruce McGill) meet on a park bench facing the White House, and Tenet tells her: “Joe is out there on his own, Valerie.” I assumed this meant: help him. But it means, to both him and her, abandon him. Which she does.

For most of the final third of the movie, Plame and Wilson are at odds. She even moves back in with her folks. She abandons him as surely as Jeff Wigand’s wife abandoned Wigand. The difference is that Michael Mann shows how this affects Wigand; Liman shows how this affects Plame. In terms of drama, it’s all wrong. For the final third of the movie, Plame is the good soldier for the wrong side and the movie doesn’t own up to it. It takes 20 minutes of screentime, plus a no-nonsense speech by Sam Shepard, Mr. Right Stuff, as her father, for her to come to the dramatically obvious conclusion that she needs to join her husband in fighting the Bush White House. Then she testifies before Congress, and Joe Wilson talks to students about the necessity of participation in a democracy, and we get a bit of flag-waving at the end. The End.

Feel dissatisfied? You should. For the following reason most of all:

The work of Woodward and Bernstein led to the resignation of Pres. Richard Nixon.

The work of Wigand and Bergmann led to one of the most successful lawsuits in the history of this country, in which the tobacco companies agree to pay $246 billion to all 50 states.

The work of Wilson and Plame led to ... the prosecution of Scooter Libby. Who was pardoned.

We don’t get the ending we want. The truth gets out there and nothing happens. Because we, as a country, don’t want to know the truth. We want our comfortable lies. For “Fair Game” to work, it needed to own up to this. It needed to show us, perhaps during the end credits, all of the lies and bullshit since that fateful spring and summer: Abu Ghraib and Pat Tillman and fake White House correspondents and firing U.S. attorneys and “You’re doing a heckuva job, Brownie” and “Keep Gov’t Out of My Medicare” and “You lie!” and birthers and Obama = Hitler. And on and on. They got away with it all and they’re still getting away with it. Their lies used to emanate from the White House and now they're directed at the White House, and, if anything, the liars have gotten bolder.

Saturday November 27, 2010

Review: “L'arnacoeur” (“Heartbreaker”) (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It’s a brilliant idea for a movie: Hire a handsome guy, French no less, to break up couples.

Immediately I thought of the unrequited lover who wants a chance, so he hires this French guy, let’s call him Alex (Romain Duris), to wedge himself in-between the girl and the dullard she’s currently dating, pry her away, then cast her adrift, where unrequited can go for it. Or maybe it’s a jilted lover who just wants a good, malicious laugh. Or maybe a girl wants to break up the couple so she can go for the guy. The possibilities seem endless. There’s always some disgruntled person on the periphery of a happy loving couple.

“L'arnacoeur” (“Heartbreaker”), a French romantic comedy by first-time director Pascal Chaumeil, quickly circumscribes the possibilities.

As the movie opens, a French couple is vacationing in the Middle East. He is, yes, a dullard who wants to stay by the hotel pool and watch a wet T-shirt contest, while she actually wants to see the country they’re visiting. To do so she hitches a ride with a rugged humanitarian (Alex), who is bringing medicine to orphans, and they connect, and fall in love, although he insists he can no longer be with anyone. But: “I’ve never felt so alive,” he tells her. “You deserve better,” he tells her. And back at the hotel she promptly dumps her jerk of a boyfriend and gets on with her life.

As the movie opens, a French couple is vacationing in the Middle East. He is, yes, a dullard who wants to stay by the hotel pool and watch a wet T-shirt contest, while she actually wants to see the country they’re visiting. To do so she hitches a ride with a rugged humanitarian (Alex), who is bringing medicine to orphans, and they connect, and fall in love, although he insists he can no longer be with anyone. But: “I’ve never felt so alive,” he tells her. “You deserve better,” he tells her. And back at the hotel she promptly dumps her jerk of a boyfriend and gets on with her life.

It’s all a pretty ruse. Later we see Alex getting paid by the brother of the girl, who couldn’t stand the boyfriend. Alex’s contract comes with a money-back guarantee and the brother asks how often he’s had to return the money. “Jamais,” Alex replies. Never. Then Alex walks through the airport in super-cool slow-motion with his team, Melanie (Julie Ferrier) and Marc (François Damiens), while in voiceover he tells us about the gig.

There are three categories of women in relationships, he says:

- Happy

- Knowingly unhappy

- Unknowingly unhappy

He concentrates solely on no. 3. Drag. Plus he doesn’t sleep with the girls. Dragger. He simply makes them realize that other men, vaguely handsome men, desire them, allowing them to dispense with whatever lame-o they’re currently dating. It’s pretty clean stuff. Rather too clean. Not only do these principles circumscribe possibilities, they actually get in the way of a good story. So they’re abandoned five minutes later to allow us our lukewarm story.

Back in Paris, Alex and his team are contacted by a man named Van Der Becq (Jacques Frantz), whose daughter, Juliette (Vanessa Paradis), is about to marry a rich Brit named Jonathan Alcott (Andrew Lincoln). Can they break off the wedding? Ca depend. They concentrate solely on no. 3s, remember. So first they have to determine if Vanessa is truly happy in her relationship. And how do they do this? By seeing what kind of man Jonathan Alcott is. They determine her emotional state, in other words, through his personality. How enlightened.

Worse, they come off like muckraking journalists rather than true investigators. At one point, disguised as panhandlers outside a fancy restaurant, they see Jonathan, inside, asking for a doggy bag. Ah ha! They assume the pejorative (doggy bag = cheap), rather than the positive (doggy bag = thrifty), but, regardless, we see the punchline a mile off. Jonathan hands them, the poor panhandlers, his food. Doggy bag = charitable.

They take the gig anyway. Alex owes gamblers and needs the money. So much for the principles he told us five minutes earlier. Hey, he lied to us in slow-motion!

The wedding is to take place in Monaco, and, to get close to Juliette, Alex passes himself off as a bodyguard hired by her father. She resists and acts the brat, but he arranges to save her from a car thief in grand, nonchalant fashion, so she allows him to stick around. And everything falls into predictable patterns. She seems to fall for him. He seems to fall for her. But there’s the fiancé, who’s a nice guy, and the mob enforcer, who isn’t.

Comic relief is provided by Marc (who has a Rhys Ifans thing going), and Juliette’s crazy friend, Sophie (Héléna Noguerra). My favorite bit is when Sophie aggressively, sexually attacks Alex in his room and Marc is sent to create a diversion. He does. He knocks her out from behind.

Question: Why do we assume that people are attracted to each other through commonalities? They research Juliette and discover she likes the music of George Michael and the movie “Dirty Dancing” so they create situations where these commonalities can be introduced. Oh, you like Wham!, too? Oh, you like “Dirty Dancing,” too? Thus they bond. But do we simply want mirror images of our own tastes? Don’t looks and personality still predominate?

To its credit, the movie never makes Jonathan a villain. He’s always a nice guy, who always loves Juliette.

In fact, I began to root against Alex. Or maybe I just began to root against the traditional romantic comedy. No, don’t bring the two stars together just because they’re the two stars. No, don’t make the girl fall for the guy who’s spent the entire movie lying to her. Surely, I thought, the French won’t let me down the way that Hollywood does.

They didn’t. Alex’s team fails for the first time, and, in a callback to the open, we see Alex walking through the airport in slow-motion and telling us who he is and what he does. “We only break up couples, we never break hearts,” he says, before adding this poignant code: “My name is Alex Lippi and today I’ve broken my own heart.”

Nice end, I thought.

Except that’s not the end.

Because at the check-in desk he suddenly realizes his life is incomplete and runs back to Monaco, literally runs, a la Benjamin Braddock, to get to the wedding before it’s too late. Juliette, more Julia Roberts than Katherine Ross, doesn’t wait, either. She runs away at the altar on her own. Eventually they run into each other on a beautiful stretch of road overlooking the sea. They catch their breath. They talk. They kiss. It’s meant to be. The End.

Blech. What’ll it cost me to break this couple up?

Monday November 22, 2010

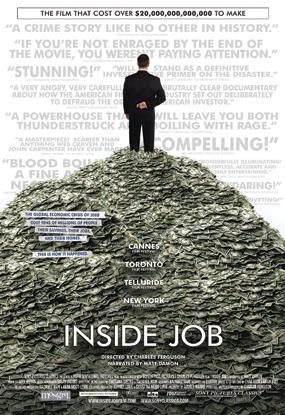

Movie Review: Inside Job (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I know very little about business and economics but I knew a lot of the information in “Inside Job,” Charles Ferguson’s documentary about the global financial meltdown of ... 2008? Just two years ago? Wow.

Ferguson puts together all of the pieces familiar to me, then adds a couple I don’t know. He clarifies and reminds.

Oh yeah, there’s Pres. Reagan deregulating the S&Ls overnight in 1982, which Ward B. Coe III and I talked about during our Q&A for Maryland Super Lawyers magazine in 2009. Oh right, Brooksley Born, the head of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, whose attempts to regulate derivatives during the Clinton years were shot down by Larry Summers , and who became the subject of that “Frontline” special I streamed off of Netflix earlier this year. Oh god, there’s Joe Cassano, the idiot head of A.I.G. F.P., and the bete noir in Michael Lewis’ Vanity Fair piece in July 2009. Oh lord, there’s Alan fucking Greenspan and Henry fucking Paulson and Phil fucking Gramm and Richard fucking Fuld and Larry fucking Summers.

It’s old home week. They got the gang back together again.

The little Don Segretti of the global financial meltdown

Except they didn’t. None of the big boys (Greenspan, Summers) agreed to sit for “Inside Job,” just as none of the big boys (Bush, Cheney) agreed to sit for Ferguson’s previous documentary, “No End in Sight,” about our missteps in Iraq after March 2003.

What sticks out in that earlier doc, though, is the he said/he said between Col. Paul Hughes, who worked for the Coalition Provisional Authority (CPA), and who seemed to have a sense of what Iraq was and what we should do there, and Walter B. Slocombe, the Senior Advisor for Security and Defense to the CPA, who arrived for a week in May, got his boots a little dusty, and helped make all the wrong decisions. Hughes seems insistent and exasperated, while Slocombe starts off almost jaunty; then, as he is questioned about, and held accountable for, his actions and policies, his eyes retreat, his voice turns tinny, he reveals himself a hollow man. One wonders what lies he tells himself to make it through the day.

The Walt Slocombe of “Inside Job” is the aptly named Fred Mishkin, an American economist who was one of six members of the Board of Governors for the Federal Reserve from 2006 to 2008. Another talking head, Robert Gnaizda, general counsel for the Greenlining Institute (a non-profit working for the disenfranchised in local communities), was aware of the problems with subprime mortgages, with predatory lending practices, with defaults and foreclosures, and he had semiannual meetings with Ben Bernanke, chairman of the Federal Reserve, to attempt to address these issues. But only in 2009 did Bernanke admit there were problems that needed addressing.

Of course Bernanke didn’t agree to be interviewed. He’s insulated and unaccountable. Ah, but there’s Mishkin, tanned beyond recognition, proudly admitting he was at the semiannual meetings between Gnaizda and Bernanke. He’s expecting softballs. Instead, Ferguson, off camera, states that Bernanke was warned and did nothing. Mishkin’s response? He collapses. He evaporates into nonsense:

Yeah. So, uh, again, I, I don't know the details, in terms of, of, uh, of, um – uh, in fact, I, I just don't – I, I – eh, eh, whatever information he provide, I'm not sure exactly, I, eh, uh – it's, it's actually, to be honest with you, I can't remember the, the, this kind of discussion.

One almost feels sorry for him, this little Don Segretti of the Global Financial Meltdown, until later in the doc, when Ferguson gets into the conflicts of interest between economics departments and industry: How industry often pays prominent academics to present viewpoints industry wants. Mishkin did this in 2006. He was paid $125,000 by the Icelandic Chamber of Commerce to coauthor a study of Iceland’s financial system and found it stable “with prudent regulation and supervision.” But “Inside Job” actually begins in Iceland, where we’re informed of the deregulation that occurred in Iceland’s banking industry in 2000, leading to insane loans, and, currently, a debt 10 times its GDP. Mishkin owns up to that. “It turns out that the prudential regulation and supervision was not strong in Iceland,” he says. So Ferguson asks the obvious follow-up: What led you to think that it was? Mishkin’s stuttering response? He seeks refuge in the passive voice and second-person point-of-view. He says all of the following:

- “You’re going with the information you have.”

- “The view was that Iceland had very good institutions.”

- “It was an advanced country.”

- “You talk to people.”

- “You have faith in the Central Bank.”

Suddenly you’re disgusted all over again. These are charlatans in prominent positions. They are hollow men. Mishkin was paid more than twice as much as I’ve ever made in an entire year to simply co-author a study...and he couldn’t be bothered with independent research. He said what they wanted him to say.

But that’s not even the worst part of the incident. The worst part is when Ferguson asks him why the title of this study, “Financial Stability in Iceland,” has been changed, in Mishkin’s current CV, to “Financial Instability in Iceland.” As if he foresaw and warned against a crisis whose hand he held all the way to the precipice:

Well, I don't know, if, whatever it is, is, the, uh, the thing – if it's a typo, there's a typo.

In “All the President’s Men,” Deep Throat notices that Bob Woodward is focusing too much on the ratfucking activities of Donald Segretti, and reminds him of the deeper issue: “They cancelled Democratic campaign rallies. They investigated Democratic private lives. They planted spies, stole documents, and on and on. Now don’t tell me you think this is all the work of little Don Segretti?”

So while it’s fun to watch Mishkin hemming and hawing on camera, it’s less important than: How we got here, what happened, where we are now.

How we got here

Rep. Barney Frank talks up the old borrower-lender dynamic—a dynamic that, even three years ago, I thought was still in place. A person borrowed, a bank lent, and the borrower paid back to the lender; and because it usually required decades to pay back, the lender was careful about who was doing the borrowing. That’s the way the world worked.

The world changed in the 1980s when brokers at Salomon Brothers, a Wall Street investment bank, created complex mortgage derivatives called collateral debt obligations, or CDOs. Per my limited understanding: The mortgages were sold from banks to investment banks, who cut them up, bundled slices with hundreds of slices from other mortgages—to spread and thus minimize the risk—and sold them to investors.

So now when you pay your mortgage, you pay, not the bank, but these investors. Of course, since banks sold the mortgages, banks could be less careful about who they loaned to; and since, with all of that bundling and slicing, risk was minimized, risk could be increased. As it was. Which is how you got subprime mortgages: loans being given to people who had no collateral and couldn’t afford the payments, and who would ultimately default. Their entry into the system drove up prices, and their exit from the system collapsed the prices. The exit almost collapsed the system.

We get some back-and-forth on who foresaw the crisis (Allan Sloan) and who didn’t (Alan Greenspan). We get a little on who began to bet against all of the subprime mortgage loans (Goldman Sachs, chiefly), and who didn’t (A.I.G., chiefly).

One of the most telling incidents, about which you could make a good HBO movie, occurred at the 2005 Jackson Hole Symposium, at which you had the usual suspects: Greenspan, Bernanke, Summers, Geithner, and where an IMF economist, Raghuram Ragan, delivering a paper, less on the nitty-gritty of subprime mortgages and CDOs, than on the larger topic of incentives and risk. Here’s narrator Matt Damon:

Rajan's paper focused on incentive structures that generated huge cash bonuses based on short-term profits, but which imposed no penalties for later losses. Rajan argued that these incentives encouraged bankers to take risks that might eventually destroy their own firms, or even the entire financial system.

Prof. Kenneth Rogoff of Harvard:

Rajan hit the nail on the head. What he particularly said was: “You guys have claimed you have found a way to make more profits with less risk. I say you've found a way to make more profits with more risk.”

The reaction to his paper? Larry Summers attacked. He accused Ragan of being a Luddite. “He wanted to make sure that we didn’t bring a whole new set of regulations to the financial sector at this point,” Ragan says.

“Inside Job” is divided into five parts—“How We Got Here”; “The Bubble”; “The Crisis”; “Accountability”; “Where We Are Now”—and should be required viewing for every man, woman and child in the United States. It won’t be, of course. So far it’s grossed $1.8 million, which works out to about 180,000 people. Out of a nation of 308 million. It's barely being seen.

I could've used more on the history of deregulation (the who and how) and on what reforms have been enacted since Sept. 2008 (if any). I also would’ve liked something on the way the crisis has been spun by the anti-regulation right. It’s doing the shit it always does: blaming the opposition for its own crimes. In this scenario, the crisis was caused by government, not the private sector. In this scenario, government is still the problem and the financial industry can regulate itself—give or take a multi-trillion-dollar bailout from the federal government. I wanted Ferguson to take these guys down. (Though he does have a nice back-and-forth with Glenn Hubbard, Chief Economic Advisor during the Bush Administration, current Dean of the Columbia University Business School, and a nasty piece of work.)

The poster for “Inside Job” shows a suited man crossing his fingers atop a pile of money. This is a key metaphor for me. I don’t know much about business and economics, but, to me, here’s what life feels like in a fairly well-off, post-industrial society.

Most of us struggle to find something we’re good at, and for which we can get paid, and, if we’re lucky, we do this thing for 40 to 50 years until we can hopefully retire with a bit of comfort. And while we’re doing this thing, we’re putting our money, bit by bit, into a room, which is where other people, bit by bit, are putting their money, too. So there’s a huge pile of money in this room. Now there’s another group of people who are attracted to this room for the pile of money. They see the pile of money and say, “That’s what I want to do.” They believe they can take that pile of money, our money, and turn it into a bigger pile of money, which will be mostly their money. But while they’re doing this magic act, they don’t want anyone to watch. Because we can trust them. Because they are self-regulating. Because what could possibly go wrong?

Monday November 01, 2010

Review: “A Film Unfinished” (2010)

WARNING: SPOILERS

As the documentary started, I had a moment of regret.

“Why am I watching this?” I wondered. “What’s it going to tell me that I don’t already know? That conditions in the Warsaw Ghetto were horrific? That evil is banal?”

Here’s the background. At the end of World War II, a 60-minute, silent documentary was found in the German archives on Jewish life in the Warsaw ghetto in the months before the ghetto was liquidated and its inhabitants shipped off to the extermination camps of Treblinka. For 45 years, the footage, among the only known footage of life in the Warsaw ghetto, was treated as fact, as documentary fact, until a fourth reel was found indicating that many of the scenes were staged by the Nazis.

“A Film Unfinished” is Yael Hersonski’s 90-minute documentary on that 60-minute propaganda film.

Thus the moment of regret. “How,” I thought, “can Hersonski make this silent film interesting?”

Three ways.

First, it’s no longer silent. She adds her own narration as well as readings from various diaries, including those of Adam Czerniaków, head of the Warsaw Judenrat (Jewish Council), and Heinz Auerswald, the Nazi commissioner of the ghetto. The victims, along with the perpetrators, have voices again.

First, it’s no longer silent. She adds her own narration as well as readings from various diaries, including those of Adam Czerniaków, head of the Warsaw Judenrat (Jewish Council), and Heinz Auerswald, the Nazi commissioner of the ghetto. The victims, along with the perpetrators, have voices again.

Two. She appreciates the power of the human face. She shows us not only the haunting faces in the silent propaganda film but the haunted faces of Warsaw ghetto survivors, “witnesses” she calls them in the credits, whom she films watching the silent propaganda film for the first time. There are five of them: four women and one man. The man has a slight smile on his face at odds with the heaviness of his sigh. The women simply looked pained. “Oh God,” one says, “what if I see someone I know?” Another: “I keep thinking I might see my mother walking.” There’s this tension between wanting to see and not wanting to see, between recovering this past and burying it forever. Will seeing her mother make things better? Or will it make the pain unbearable?

Finally, there’s the mystery. In the opening narration, Hersonski says the Third Reich was “that empire that knew so well to document its own evil,” but one still wonders why they filmed this particular piece of propaganda. What purpose did it serve? The staged scenes tend to feature better-off Jews going about their day: a woman putting on lipstick in her vanity mirror, another woman buying goods at the butcher, couples dining out. The witnesses refute each of these instances. “Most had sold everything.” “They were waiting to die.” “You woke up to find a corpse every 100 meters.”

Czerniaków’s diary details what was being filmed that day, the subterfuge that went into the filming, and then we see the footage. This bris, that ball, this show. The Jews in the show’s audience were held there all day, without food, without bathroom breaks, and ordered to laugh for the cameras.

Initially one thinks the Nazis are doing the obvious: showcasing comfortable people to refute claims of horrible conditions. Except they also showcase the horrible conditions.

We see piles of garbage. People were too weak to go downstairs, one witness says, so they simply threw garbage out the window. “I was 10 years old at the time,” another witness says, “and I was the dominant figure in my family.” She escaped the ghetto several times a week, risking her life, to get food for her family.

We see emaciated people with shaved heads. We see children in rags. We see a corpse every 100 meters. The Nazis filmed it all.

The point of the filming was, in fact, this juxtaposition. Here’s take 1, take 2, take 3 of a well-off woman buying meat at the butcher while children in rags starve outside. Here’s take 1, take 2, take 3 of sated couples leaving a restaurant and ignoring the emaciated woman in rags begging for a handout.

Much of the footage was taken by Willy Wist, a German cameraman who testified during the war-crime tribunals in West Germany in the 1960s, and whose words, read by German actor Rüdiger Vogler, constitute less the banality of evil than the shrug of it. He didn’t know the ultimate purpose of the film; he just filmed it. He says, at one point, “I recall I had to film a mass grave,” and then we see that footage. A makeshift slide was created to deliver the corpses into the pit outside Warsaw. One lifeless, naked body after another slides down and lies crumpled at the bottom. It’s the final solution foreshadowed, and Wist filmed it all because it was his job to film it all. If this seems unforgivable it’s because it reminds us of us. We see a line, we thank the stars we’re on this side of it, and we continue to do what we do.

It may be obvious, as you read this, why the Nazis staged what they staged—the ultimate purpose of their silent propaganda film—but it wasn’t to me watching Hersonski’s doc until about three-quarters of the way in. Was it explained outright? Was it implied? I forget. Hersonski’s narration tends to be quiet and even, and she presents most of the material without editorial comment. In this restraint she shows her artistry. “You’ve got to hold something back for pressure,” Robert Frost once wrote, and she does, and that pressure builds, and eventually, either nudged by her or by some spark in my brain, it hit me, the answer, and I felt a fresh horror wash over me.

The juxtaposition between rich and poor Jews was justification. The Nazis were pretending to document a race of people so indifferent to the suffering of others that they didn’t deserve to live. They were documenting an excuse for extermination.

In that moment of horror, of revelation, one understands the true meaning of propaganda.

It is the powerful blaming the powerless for the crimes of the powerful. The Nazis herded 600,000 Jews into a single zone of Warsaw. They gave them no way to live. They let them starve. They let them die by the hundreds of thousands. Then they staged scenes of supposed Jewish indifference to the suffering of others.

I sat down for “A Film Unfinished” almost regretting sitting down. What else could I learn about the Holocaust that I didn’t already know? But there’s always fresh horror. The redemption, if there is any, is that the Nazis created a document of lies, and, from this, Yael Hersonski created a document of truth. She restores voices, and faces, and meaning.

Sunday October 31, 2010

Review: “Tangshan dadizhen” (2010)

XIAO XIN: SPOILERS

I knew going in that Feng Xiaogang's “Tangshan dadizhen” (“Aftershock”) focused on the Tangshan earthquake of 1976 that killed 240,000 people. I knew the movie set the all-time box-office record in China this year. And that’s about all I knew. So I spent much of the movie trying to figure out what the movie was about.

It begins well. We’re told it’s July 27, 1976 in Tangshan City, a train goes by, and it’s followed by a dragonfly. Then two. Then thousands. The people waiting at the railroad crossings are freaked, astonished, puzzled. “Daddy,” a little girl in a truck says, “why are there so many dragonflies?” The father tilts his head out the window. “A storm must be approaching,” he says.

Cue: title.

That’s not bad.

There are early touches that reminded me of early Spielberg. We follow this family, the Fangs, whose two kids—a boy (Fang Da), and a girl (Fang Deng), twins—noisily request popsicles, fight and run from bullies, and share, with mom, the benefits of a new electric fan on a hot, summer day. I'm not sure my mind would’ve turned to Spielberg without knowing this movie set the box-office record in China, but at the least there’s a broadly drawn cuteness here that would’ve fit just as easily into an Arizona suburb.

There are early touches that reminded me of early Spielberg. We follow this family, the Fangs, whose two kids—a boy (Fang Da), and a girl (Fang Deng), twins—noisily request popsicles, fight and run from bullies, and share, with mom, the benefits of a new electric fan on a hot, summer day. I'm not sure my mind would’ve turned to Spielberg without knowing this movie set the box-office record in China, but at the least there’s a broadly drawn cuteness here that would’ve fit just as easily into an Arizona suburb.

That night, as the kids are sleeping, and as the mother and father, at his late-night construction job, make love in the back of his enclosed truck, there’s more ominous foreshadowing. The sky turns purple and the little girl’s fish jump right out of the fishtank. The Tangshan earthquake registered anywhere from 7.8 to 8.2 on the Richter scale, and its death toll makes it the most disastrous earthquake of the 20th century. Pipe mains burst, buildings give way, heavy objects—boom—crush people indiscriminately. It’s brutal. People run, but from what? To what? There’s no safety. Mom and Dad struggle to make it back to the kids. At the window, the little girl cries for her mom. Mom cries back: “Lie-le!” (“I’m coming!”) But the father spins the mother out of the way, and to relative safety, just as the building collapses with the kids in it. Pretty horrific. We see them go down like Leo in “Titanic.”

An earthquake can only last so long, though—Tangshan’s lasted 23 seconds—and we’re just 10-15 minutes into the movie. At this point I’m wondering: “What is this film going to be?”

What the film is going to be

When the dust settles, both kids and father are trapped, but alive, so I thought, “Oh, this will be about the struggle to get them out. It’ll be like ‘World Trade Center.’”

Then aftershocks hit and the father dies. The twins are still trapped beneath opposite sides of the same concrete slab, and the mother begs neighbors and workers—those small Chinese men in boxers and flip-flops who can lift refrigerators on their backs—to get them out. To lift the concrete slab, unfortunately, the weight has to go on one side. One child will be crushed in order to save the other and the mother has to choose: Which child do you save? Which child do you kill? It’s an impossible choice. But as the men are about to leave to help others, she shouts, suddenly, and then says, quietly, horrified, “Jao Di Di” (“Save little brother”).

“Oh,” I thought. “So it’s like ‘Sophie’s Choice.’ A mother has to live with the consequences of sacrificing one child in order to save another.”

A moment later, the mother carries her daughter’s broken body and places it next to the father’s broken body. Then she and her son, the only two members of the family to survive, make their way, with other survivors, out to relief stations set up by the Chinese army, who are making their way into the devastated city.

Except the girl is not dead. A rain falls and she rises, blinking one eye. (The other is swollen shut as if she’d just gone 15 rounds with Apollo Creed.) I’m not sure what to make of this resurrection. Her death was greatly exaggerated? Her father’s spirit somehow revived her? We do know that while the concrete slab apparently didn’t crush her body, her mother’s choice, which she heard from beneath the rubble, crushes her spirit. The vivacious and mouthy little girl we knew for the first 10 minutes of the movie is gone, replaced by a blank, mute girl. Ultimately she’s adopted by two officers of the Chinese army, and they rename her Ya Ya, but, speaking up for the first time since Mom’s choice, she insists on being called “Deng,” even as she’s willing to give up the “Fang.”

The boy, meanwhile, has lost his left arm, and he’s about to lose his mother. In one of those really Chinese cultural moments, the mother of the now-dead husband, the grandmother, insists, in that roundabout Chinese way, of raising the child herself, while the boy’s actual mother, with apparently no rights in the matter, acquiesces. But just as the bus is pulling away, the boy’s aunt, finally speaks up and shames the grandmother. At this point we see it all from the mother’s perspective. The bus rumbles down the dirt street. Then it stops. The doors open. And out comes little Fang Da running towards her. It’s a hokey moment but hokey works. I choked up.

Of course I’m waiting, with everyone, for the twins to reunite. But suddenly it’s 1986 and Deng is going off to med school while Da is starting a pedicab business; and then it’s 1995, and Deng has an out-of-wedlock child, a daughter, whom she couldn’t abort because of her own mother’s choice to, in essence, “abort” her, while Da is married and running a successful business but dealing with conflicts between his wife and his mother, the original Chinese martyr. “Oh,” I thought. “This is a decades-long melodrama. Like ‘Giant.’”

And it just continued. The movie takes us from the Tangshan earthquake of 1976 to the Sichuan earthquake of 2008 (8.0; 68,000 dead), where the twins, both volunteers, finally reunite (interestingly, off-screen). The movie is about how this family is broken and how it comes together again. It’s also about how Tangshan is broken and comes together again. Reduced to rubble in 1976, it is, by the end, a glittering metropolis. Could it ultimately be about how China is broken and comes together again? The 1976 section ends with Mao’s funeral, with China reduced to economic rubble, and takes us to today, with China a world economic power, and with all of our main characters, with their heavy heartaches, living in relative comfort. They have risen.

And that’s when I finally got it. “Oh,” I thought. “It’s the national story told as one family’s soap opera. Or the national soap opera told through one family. It’s ‘Gone with the Wind.’”

Thus its popularity.

Broken record

At the same time, setting “the all-time Chinese box office record” doesn’t mean much these days. The record it broke, “Avatar’s,” was set earlier this year, while the record that one broke, “2012,” was set in 2009, while the record that one broke... etc. Box-office records are broken all the time in China now for a reason. More theaters are being built, and more Chinese have the leisure time and disposable income to see filmed stories that solidify national myths: I.e., this is a story about how we got to the point where we could waste our time watching this.

Welcome to the party, pengyoumen.

Monday October 25, 2010

Review: “Hereafter” (2010)

WARNING: UNDISCOVERED COUNTRY SPOILERS, FROM WHOSE (JASON) BOURN NO TRAVELER RETURNS

“Hereafter” needs a subtler touch than director Clint Eastwood brings. Eastwood has a nasty habit of choosing sides. His is all good, the other is all bad, and doubt and ambiguity are for saps (or, in Eastwoodian, “punks”). This is true if the subject is a San Francisco cop, a lady boxer, or the most important question human beings can ask:

What happens when we die?

Every religion in the world, and half the charlatans, promise to answer that question. Eastwood, and screenwriter Peter Morgan (“The Queen”; “Frost/Nixon”), now do. Without doubt or ambiguity. You got a problem with that...punk?

We get three main storylines. In the first, a pretty French TV journalist, Marie Lelay (Cecile de France), finds her career, and life, sidetracked after she is swept up in a tsunami and dies for an unspecified amount of time. This tsunami is monstrous and terrifying and the best part of the film. After getting knocked out, Marie drifts in the water while a toy bear, floating above her, stares down. We hear a heartbeat until we don’t. The screen goes dark. Then we get blurry images, silhouettes, and mumbling. It’s like that scene in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” when the aliens emerge from their spaceship. Are these silhouettes the living, whom she is leaving, or the dead, who are greeting her? At first I assumed the latter, but then two silhouettes move towards us, and one gives us a sense of resuscitation, and, voila, suddenly we’re back, with someone on a rooftop giving Ms. Lelay mouth-to-mouth. Enjoy that scene. The movie is called “Hereafter” but this is the last glimpse of the hereafter we’ll get.

We get three main storylines. In the first, a pretty French TV journalist, Marie Lelay (Cecile de France), finds her career, and life, sidetracked after she is swept up in a tsunami and dies for an unspecified amount of time. This tsunami is monstrous and terrifying and the best part of the film. After getting knocked out, Marie drifts in the water while a toy bear, floating above her, stares down. We hear a heartbeat until we don’t. The screen goes dark. Then we get blurry images, silhouettes, and mumbling. It’s like that scene in “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” when the aliens emerge from their spaceship. Are these silhouettes the living, whom she is leaving, or the dead, who are greeting her? At first I assumed the latter, but then two silhouettes move towards us, and one gives us a sense of resuscitation, and, voila, suddenly we’re back, with someone on a rooftop giving Ms. Lelay mouth-to-mouth. Enjoy that scene. The movie is called “Hereafter” but this is the last glimpse of the hereafter we’ll get.

The second storyline follows George Lonegan (Matt Damon), who, as a child, had a near-death experience, and ever since, whenever he touches someone, zap, he can communicate with this person’s deceased loved ones.

(BTW: Do the communicatees have to be “loved ones”? And are they the deceased who mean the most to this person or the deceased for whom this person means the most? Might George touch my hands, for example, and suddenly be talking with someone I barely knew but who secretly loved me and is just, you know, hanging around? Are there stalkers in the hereafter?)

George’s older brother, Billy (Jay Mohr), a businessman, wants to exploit this talent—he’s developed a website and everything—but George wants to ignore it completely because the after-effects are somewhat deleterious. The connection isn’t immediately broken and he seems not quite there, floating in this middle kingdom, listening to dull radio fully-clothed in bed. “A life about death is no life at all,” George tells his brother. So he’s trying something else: a working-class job at the C&H plant and a once-a-week Italian cooking class to meet people. Mostly, though, he’s alone. Eastwood does alone well but he does it too often here. I think we get three shots of George eating by himself while a guitarist on the soundtrack picks out a few lonely chords.

If that’s not pathos enough, there’s the London storyline, Marcus and Jason (Frankie and George McLaren), twin boys who save their pennies, or maybe their ha’ pennies, to pay for a self-portrait for their mum, who, alas, is a drug addict. It’s like something out of a silent melodrama: They care for her with one hand while fending off social services with the other. One morning she sends Marcus on an errand, but at the last instant, Jason, the more talkative, baseball-cap-wearing brother, goes, and I immediately thought, “OK, he’s dead.” It reminded me of the anxiety accompanying the first scenes of the HBO series “Six Feet Under”: Who’s going to die and how? Here we know who; it’s all about how. Ah, bullies: Eastwood’s favorite trope. No wait, Jason runs from the bullies. So he’ll run right into an oncoming car, right? Wrong. It’s an oncoming truck.

Those are our three storylines—all related to death and the hereafter. One assumes they’ll connect eventually. And they do—eventually—but Eastwood's 80 now, and like any 80-year-old he takes his time getting there.

In the meantime: Lelay takes a leave of absence from her weekly news-magazine show to write a revisionist bio of former French president Francois Mitterrand, dead now 10 years, but turns in three chapters on the hereafter instead. She’s shocked that her publishing house isn’t interested, and shocked again when her weekly show, and accompanying Blackberry ads, go to a younger, Asian-y woman. She was so proud of those ads.

Lonegan begins a flirtation with a cute woman in his cooking class, Melanie (Bryce Dallas Howard), in which each’s interest in the other is obvious. But during prep for a home-cooked meal, his secret, his superpower as it were, is slowly revealed; and when she insists he try it on her, he finds out things she doesn’t want revealed. And there goes that. He’s back to eating alone while the guitarist plucks a few lonely chords.

Marcus, meanwhile, is put into a foster home with well-meaning parents, but he’s quiet, and wearing Jason’s baseball cap, and doing whatever he can to communicate with Jason. This includes visiting charlatans who claim to communicate with the dead.

In this way, each character deals with a perhaps culturally specific response to their association with the hereafter. Marcus gets British charlatans. Lelay, who definitely experienced something when she died, gets the French, the center of modern, progressive culture, who definitively know nothing happens. We just die. C’est tout. And Lonegan definitely communicates with the dead, but instead of treating this as the greatest discovery in the history of mankind, which it is, his brother treats it as a way to make a coupla bucks. So American.

Eventually (there’s that eventually), all three converge at a convention for a dying industry (books) in London. Marcus is with his foster parents, Lonegan, who loves Dickens, is attending a Derek Jacobi reading of “Little Dorrit,” and Lelay is shilling her book in stilted English.

Lonegan, lonely boy, is of course enamored of Lelay, chic Frenchwoman, but does nothing with it. (Welcome to the party, pal.) Marcus, meanwhile, recognizes Lonegan and convinces him to use his superpower to communicate with Jason.