Friday September 08, 2023

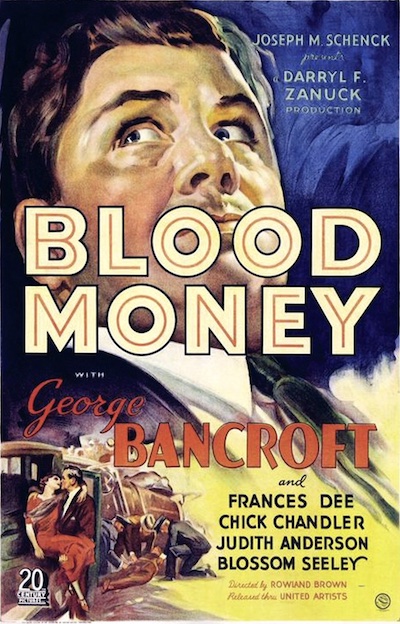

Movie Review: Blood Money (1933)

Dee with Dietrich lighting; Dalton Trumbo called her character “a thrill-seeking little bitch.”

WARNING: SPOILERS

This came onto my radar because of a good chapter on writer-director Rowland Brown in Philippe Garnier’s book “Scoundrels & Spitballers: Writers and Hollywood in the 1930s.” Except I can’t remember if the movie sounded interesting or Brown did. Stuff like this keeps happening to me. My streaming queues, for example, are filled with films that were part of some important late-night research, but now I look at them and go, “Um … OK?” Whatever rationale I had for watching them is gone.

“Blood Money” isn’t great but it deserves a wider audience and a better print. (I watched it via an avi file on my computer—not ideal.) The film gets into class issues, and gender issues, and it has wit and a cynical sense of the world. People want what’s bad for them and run toward ruin with open arms. Sadly, we get a happy ending.

A thrill-seeking little bitch

We keep hearing about our main character before seeing him. (Cf., Rick in “Casablanca.”) A wife betrays her husband to the cops, he belts her, then tells her to get Bill Bailey on the line. A judge is awakened in the middle of the night with a bond request. “That Bill Bailey has a lot of nerve!” the wife says. Then it’s onto the working class. A butcher, weighing sausages, says Bill Bailey ordered 150 turkeys for Thanksgiving. For charity? “Sure,” he responds. “For our poor judges, our poor lawyers, and our poor police officers.”

When we finally see the man (George Bancroft), he’s ringside at a prizefight, sponsoring a boxer with the just-sitting-there slogan “Bailey for Bail.” When someone says he hasn’t picked a winner all night, he smiles and says, “I make all my money off losers.”

So there he is: a Tammany Hall-type grifter with the world wrapped around his finger. What brings him low? A woman, of course.

She’s a new client who needs $1.5k bail and uses a $6k ring for collateral. That sends his antennae up. She says her name is “Jane Smith” (up again), and, eavesdropping, he discovers she’s from money: Elaine Talbert (Frances Dee), the daughter of the president of a Hawaiian pineapple company. She’s also wild—someone who steals for the thrill of it. Example: While he’s helping her post bail, she lifts his cigarette lighter. Later, when they’re going for burgers and onions, and she lights her cigarette, he takes it, sees it’s his—inscribed to him from Jack Dempsey—and gives her a look. Suddenly she’s in her element. She leans back with a saucy smile and “So … what?”

She’s a new client who needs $1.5k bail and uses a $6k ring for collateral. That sends his antennae up. She says her name is “Jane Smith” (up again), and, eavesdropping, he discovers she’s from money: Elaine Talbert (Frances Dee), the daughter of the president of a Hawaiian pineapple company. She’s also wild—someone who steals for the thrill of it. Example: While he’s helping her post bail, she lifts his cigarette lighter. Later, when they’re going for burgers and onions, and she lights her cigarette, he takes it, sees it’s his—inscribed to him from Jack Dempsey—and gives her a look. Suddenly she’s in her element. She leans back with a saucy smile and “So … what?”

Dee is dynamite—both senses. She has a lovely neck, and can play both good girl and bad. The good is a front. The bad is, too, in its own way. She wants to be bad but she also wants to be punished. “I want a man who’s my master, who isn't afraid of anybody in the world, who’d shoot the first man that looked at me,” she tells Bailey at a Hawaiian luau on her father’s estate.” If only a man would give her a thrashing, she adds, “I’d follow him around like a dog on a leash.” In his review in The Spectator, Dalton Trumbo called her “a thrill-seeking little bitch.”

Bailey’s response to all this? He falls for her like a sap. He turns into the opposite of what she wants.

When does he fall? That’s a good question. Earlier we see him hanging with Ruby Darling, a laconic female gangster/nightclub owner played by Judith Anderson in her film debut. (Yes, Mrs. Danvers from “Rebecca” is the initial love interest.) “Aw, Ruby,” he tells her, “I could never get stuck on any girl but you.” But then Elaine shows up. What tips him? When she wants her burger smothered in onions, and he says he always wanted to meet a girl who really liked onions? When she steals his lighter? The longer they’re together, the less interesting he becomes. It’s called love.

At the dog-race track, Bailey buys a dog for her and she’s beside herself with joy; when the dog finishes last, she mutters, “Where’d you get that mutt?” In a sense, the dog is Bailey. As soon as he introduces her to a sleeker model, Ruby’s brother Drury (Chick Chandler), a bank robber known as the “Lone Bandit,” her eyes get like saucers, and Bailey becomes the mutt. There’s a nice scene later at a golf course when Bailey and Drury make calls in adjacent phone booths—both to her. Another nice scene occurs after Elaine kisses Drury goodnight on the cheek and he returns to his apartment building—to find Bailey standing in the shadows. Does Bailey know? Is he angry? Neither. He’s solicitous. While dabbing the lipstick off his cheek with a handkerchief, he warns that the cops are closing in and Drury should jump bail and leave the country.

Drury: I think I’ll go to Russia.

Bailey (chuckles): They’ll put you to work there…

Instead Drury lams it with Elaine, but beforehand tells her to take the $50k to pay Bailey for the bond he’s jumping, then destroy the $300k in worthless registered bonds he stole. Except she gives him the bad bonds, and that’s the bonehead move that sets up the rest of the film. Thinking himself betrayed, Bailey works with the cops to bring Drury back. So Ruby calls a meeting to call out her protégé/lover, and the gangsters gang up on Bailey. They tell everyone to jump bail so it’ll sink Bailey’s business; then his safe is blown up and the stolen bonds are found. Now he’s looking at jail time himself.

But—final reel—Drury find outs how Elaine betrayed Bailey, sends word to sis, and she rushes to save Bailey before an eight ball laden with explosives (yes) blows up in his face. “You’ll always be getting behind an eight ball, darling,” she says, as they kiss and make up, “and I’ll always be pulling you out.”

That’s the dull part. The part that sticks is our final scenes with the thrill-seeking little bitch. Elaine shows up at Bailey’s, too, just in time to see the kiss, and when she leaves she bumps into a woman who’s distraught because a man placed an ad for a modeling gig then pawed her. “My arms are black and blue!” she cries. Which is when Elaine’s eyes light up, she grabs the ad, and off she goes—toward what she’d always wanted.

Decking Dempsey

“Blood Money” is from 20th Century Studio, pre-Fox, and produced by Darryl Zanuck, post-Warners. In its trivia section on the film, IMDb lists several of the film’s debuts and finales:

- Adalyn Doyle's debut

- Frances Dunn's debut

- Final film of Sandra Shaw

- Final film of Blossom Seeley

- Theatrical movie debut of Dame Judith Anderson

Beyond Anderson, most of these are bit players—save Blossom Seeley, who was a big star as a San Francisco jazz singer in the 1910s. In Ruby’s nightclub, she belts out “San Francisco Bay” and “Melancholy Baby.”

At the luau, we also get a sexy hula dance from an actress named Grace Poggi, who was only 19 at the time, and only made 15 films, usually as a dancer. She pops.

The big problem with the movie may be the lead. I loved Bancroft in Sternberg’s “Underworld” but he’s hardly a leading-man type. He’s good with bluster and brutism but not affairs of the heart. This movie doesn’t play to his strengths.

The previous films Brown directed were “Quick Millions” with Spencer Tracy and “Hell’s Highway” with Richard Dix. Would love to see both. He also wrote for two Cagney films, “The Doorway to Hell” and “Angels with Dirty Faces,” and is given credit, by Pat O’Brien at least, for much of what was good with the latter. “Brown wrote it, no doubt about this,” O’Brien said in 1975. “He was sort of a genius, that guy. … He talked to you like a stevedore would, in plain old everyday American.” Brown is also one of the two screenwriters (among eight writing credits altogether) on the Constance Bennett movie “What Price Hollywood?” which is basically ur-“A Star is Born.”

Brown had gangster connections, or didn’t, drank too much, or not at all, and once sparred with Jack Dempsey and maybe knocked him down. Even Garnier has a tough time getting a handle on him. Either way, “Blood Money” is the last time Brown got credited as director. He was either fired a week into “The Devil is a Sissy,” or filmed the whole thing but was told by Eddie Mannix that MGM’s go-to director W.S. Van Dyke would get credit because his name would sell better. So Brown hit Mannix—either with a phone book or the script—and there went directing. And now he was on the downhill side. That price, Hollywood.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)