Movie Reviews - 2009 posts

Monday October 26, 2009

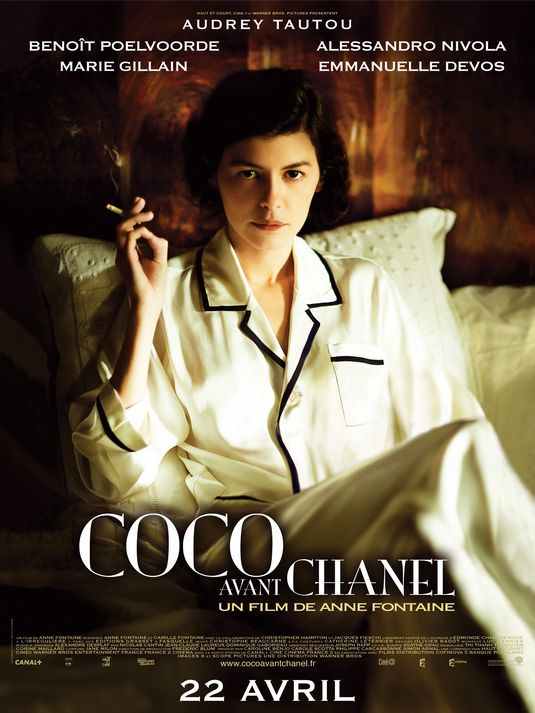

Review: “Coco Before Chanel” (2009)

WARNING: SIMPLE, ELEGANT SPOILERS

A story has a dramatic arc, a life doesn’t. That’s always been the problem with biopics. So you understand why filmmakers such Anne Fontaine, who directed and co-wrote “Coco Avant Chanel,” decide to dramatize a portion of the life rather than the whole, long, messy thing. You also understand why Fontaine chose this portion of Chanel’s life: the portion—for those whose French is worse than mine—before she became a fashion icon. People like watching people rise. Audiences are made up of folks with unfulfilled dreams who enjoy sitting in the dark watching someone with whom they can identify fulfill theirs.

So why doesn’t the movie work? Does the title character remain too unknowable? Is her love affair with Arthur “Boy” Capel too uninteresting? Are the clues to how she will eventually transform the fashion world, and thus the world—having women dress for women, and for comfort, rather than in the confining corsets and plumy hats and long heavy dresses of the period—too facile? Does the movie not care enough about why she matters (fashion and proto-feminism) in favor of why she doesn’t (love love love)?

Qui Qu'a Vu Coco

The movie begins when Gabrielle Chanel, age 10, all big dark eyes, is deposited at a Catholic orphanage and casts a final, bewildered glance at the carriage driver, seen in quarter-view, who, one assumes (correctly), is her father. Historically, this orphanage was where Gabrielle learned to be a seamstress, and where, one suspects, the austerity and simplicity of the nuns’ habits made an impression on her fashion sense, but we only get glimpses of this. We mostly take away a sense of powerlessness and loneliness in echoing hallways.

The movie begins when Gabrielle Chanel, age 10, all big dark eyes, is deposited at a Catholic orphanage and casts a final, bewildered glance at the carriage driver, seen in quarter-view, who, one assumes (correctly), is her father. Historically, this orphanage was where Gabrielle learned to be a seamstress, and where, one suspects, the austerity and simplicity of the nuns’ habits made an impression on her fashion sense, but we only get glimpses of this. We mostly take away a sense of powerlessness and loneliness in echoing hallways.

Cut to: A music hall during the belle époque, where Gabrielle (now Audrey Tautou) and her sister, Adrienne (Marie Gillain), perform the song “Qui Qu’a Vu Coco,” before rowdy crowds, then mingle with the guests, mostly upper-crust military officers and barons. Gabrielle, quickly dubbed “Coco” after the song, is a lousy mingler, but she pares (and pairs) nicely with Etienne Balsan (Benoit Poelvoorde), who is rich, cynical, out for a good time, and amused by Coco’s bluntness. Coco’s sister becomes the mistress of one Baron, but Balsan leaves for his estate in Compiegne without proffering an invitation to Coco. So she simply shows up.

The belle époque was the beautiful time for aristocrats like Balsan, not poorhouse candidates like Coco, and she bristles under the strictures of their unequal relationship. So do we. At first he keeps her hidden. When she emerges, he wants her to perform. She disapproves of the waste and frivolity of the upper classes, and wants work, but wonders what she can do. Sing and dance? Become an actress like Balsan’s frequent guest, and former lover, Emilienne d'Alençon (Emmanuelle Devos)? All the while Coco becomes known for her simple, freeing, boyish fashion sense. Emilienne keeps asking about her hats. Can you make me one? Here’s my rich friend. Can you make her one?

The story is obviously moving in this direction but the title character doesn’t seem to realize it. Is this good? An example of life happening while you’re busy making other plans? Or is it bad: The filmmaker’s assumption (film-in-general’s assumption) that audiences are only interested in what Gore Vidal famously called love love love?

Yes, Coco falls in love, with British coal magnate “Boy” Capel, and off they go for a weekend by the sea, where she gets the inspiration for the striped sailor’s shirt and the little black dress. Productive weekend! There’s a good scene in the tailor shop where she lays out her black-dress specifications, resisting, all the while, the tailor’s polite push toward the conventional. Him: It should be peach tones. It should have a corset. It should have a belt. Her: Non, non, non.

Coco’s happy with Capel but he’s got a secret—he’s marrying British money—and Balsan spills the beans, partly from jealousy, partly because he cares about Coco and doesn’t want her hurt. Balsan’s role throughout is reminiscent of Bror Blixen (Klaus Maria Brandauer) in “Out of Africa”: the disreputable man the heroine is stuck with but uninterested in, even though he’s the most interesting character onscreen. He has a laissez faire bluntness that’s fun and vaguely sexy. He even proposes to her.

Instead she starts a hat shop in Paris. Finally! one thinks. Ten seconds later, a woman says, “Look, a gentleman.” Oh no! one thinks. Yeah, it's “Boy” Capel. More love-making. More promise-making. They’ll have two months by the sea. Then he dies in a car accident. She sees the wreck. She cries. Then she makes dresses, puts on a fashion show, and everyone applauds. FIN.

XXX

The movie is based on a book by a woman, written and directed by a woman, yet it almost feels sexist in how much it ignores why Chanel is relevant. Maybe fans already know too much about her career and wanted the gossip. Maybe people always want the gossip.

Me, I knew little about Chanel going in so it was all news. At the same time, the movie left me wondering to what extent she was part of a trend and to what extent she was ahead of the trend. Did she single-handedly put women in pants? In this fact alone you see the redefinition of beauty in the 20th century. Voluptuous women look better in dresses, thinner women in pants. With women in pants, western society’s definition of beauty shifted from the zaftig to the thin. Coco was not considered beautiful, then helped redefine beauty closer to how she looked. Not bad! This shift also led to anorexia. There are corsets in the mind no fashion designer can remove.

In the end, “Coco Avant Chanel” has some of the realism of French films but also the glossy, dishonest feel of Hollywood films. “In order to be irreplaceable,“ Chanel once said, ”one must always be different.” This one isn’t.

Friday October 23, 2009

Review: “More Than a Game” (2008)

WARNING: DRAINING 3-POINT SPOILERS FROM THE LINE

“More Than a Game,” Kristopher Belman’s documentary about five friends, including a hanger-on named LeBron James, who become high school basketball stars at St. Vincent-St. Mary in Akron, Ohio in the early 2000s, should appeal to fans not only of basketbal and LeBron, and not only to coaches everywhere, but to anyone who has to create a Superman story. The dramatic problem with Superman has always been his invincibility. Who can possibly stop him? The dramatic problem halfway through this documentary, as St. V’s Fightin' Irish regularly demolish teams by 40 or 50 points, is the same. Who can possibly stop them?

This question is answered twice. The first answer is indicative of human nature. The second answer is indicative of a sadder, tawdrier aspect of American culture.

They were the “Fab Four” of Akron basketball—LeBron, Sian Cotton, Willie McGee and Dru James III—who first came to national attention in 1997 when, in junior high, they played at the AAU “Shooting Stars” Boys Basketball Tournament in Florida. “We were a team from Akron nobody’d ever heard of,” LeBron remembers. They wound up in the finals but lost, 68-66, to the previous year’s champs from southern California, when LeBron’s half-court shot at the buzzer bounced off the rim. He’s interviewed about it in the doc. He still looks pissed.

They were the “Fab Four” of Akron basketball—LeBron, Sian Cotton, Willie McGee and Dru James III—who first came to national attention in 1997 when, in junior high, they played at the AAU “Shooting Stars” Boys Basketball Tournament in Florida. “We were a team from Akron nobody’d ever heard of,” LeBron remembers. They wound up in the finals but lost, 68-66, to the previous year’s champs from southern California, when LeBron’s half-court shot at the buzzer bounced off the rim. He’s interviewed about it in the doc. He still looks pissed.

By this time LeBron was already distinguishing himself from the others, and everyone assumed he would play for John R. Buchtel High School, a mostly black public school with a powerhouse basketball program; but he didn’t even decide. Dru did. Entering ninth grade, Dru was still under five feet tall and Buchtel wouldn’t have him so he wouldn’t have them, and his friends, loyal to a fault, followed him to St. Vincent, a mostly white, Catholic school without much of a basketball program. With the help of Coach Keith Dambrot and assistant coach Dru James, Little Dru’s father, who had coached the boys in “Shooting Stars,” they gave it one.

That’s what this doc is about, really: loyalty; teamwork. One may rise above, he may even get on the cover of Sports Illustrated as a high school junior, but he can’t win a team sport without a team.

It’s also about disloyalty, or perceived disloyalty. After the “fab four“—and, with the addition of Romeo Travis, the “fab five”—win state titles in their freshman and sophomore years, going 23-1 and 27-0 respectively, Coach Dambrot, forgetting promises made to the boys, puts his career or family first, and takes a job with the University of Akron. “I never even talked to him again,” LeBron says. Coach Dru became their head coach.

The doc, too, is no one-man show. It draws out the others. Willie is the quiet, mature one; Sian the funny, fat one. Romeo doesn’t really fit in at first. He’s selfish and angry, but I like his admission that, “I never thought basketball would be my future. I just wanted to play because it’d get you girls.” My guy, no surprise, is Little Dru, all 4’ 11” freshman year, but determined to overcome what he couldn’t control, sinking threes the way other guys sink layups. His dad was also the coach, and tougher on him for that reason, which led to issues of its own—despite the fact that the dad only became coach for the son. Coach Dru was actually a football guy. He had to learn basketball.

So halfway through the doc, St. V becomes a Divsion II school, and Coach Dru puts the boys on a national traveling schedule. Keep in mind: These are five guys from the same neighborhood competing against high school powerhouses that draw talent from all over the nation. And they’re winning games 100-50. One reporter calls them the greatest team in high school history.

So what can possibly stop them? Hubris. That’s our first answer. They don’t practice as hard. (Why should they? They're not going to lose.) They don’t listen to Coach Dru as much. (What does he know that they don't?) Their games are so popular they have to play at the local university arena, and the games are still sold out, and tickets are scalped. They’re like a rock band: Groupies follow them and parties anticipate them. And in the finals of the state championship their junior year, they lose, stunningly, 66-63. Everyone blames the first-year coach, who couldn’t win a state championship with juniors who won it as freshman. It’s unfair but in a way he agrees. “I got caught up in the winning and losing,” Coach Dru says. “My job wasn’t about basketball. It was about helping them become men.”

The next year he does. Plus LeBron, who can’t stand losing, is now more determined than ever. Can you imagine? A team that routinely wins 100-50 is now more determined? The amazing thing, truly, given the media attention, the girls and the talent, isn’t that hubris stopped them once; it’s that it didn’t keep stopping them. It’s that they, and particularly LeBron, didn’t let their good fortune lead to bad. He kept a level head. The doc makes it clear that this happened, in part, because of his early bad fortune. He was born to a teenage mom and never knew his dad. “We probably moved 12 times,” he says. “The hardest thing for me was meeting new friends, [and] I wanted to have some brothers I could be loyal to.” He found them. He kept his friends close and his enemies at bay.

Of course enemies always gather. We build up to tear down in this country—buildings and people—and after the build-up of LeBron came the tear-down. Wait, why was this high school kid driving around in an $80K Hummer? Turns out his mom bought it for him via bank loan based upon her son’s future earnings. That’s icky but legal. But wait! LeBron accepted two retro jerseys (Wes Unseld and Gale Sayers) for appearing on the wall of a sporting goods store? We can’t have that. And with only a handful of games left in the season, and the team climbing the national rankings—from 23 to 19 to 16 to 11 to 9—the Ohio High School Athletic Assocation stripped LeBron of his eligibility.

That’s the second answer to what can stop them. File it under the smallness of people. At the same time the doc needed this dilemma to give its story drama. Every hero needs a villain, and sometimes the villains don’t show until the hero does. Wasn’t that what “The Dark Knight” was all about?

St. Vincent did play one game without LeBron. They still won, 63-62. Then LeBron went to court (the other kind) and the judge reinstated him. And that’s the last thing that stopped them.

Comparisons will inevitably be made to “Hoop Dreams,” the 1994 documentary about two inner-city high school basketball players, William Gates and Arthur Agee, and how injuries and circumstances kept them from their dreams; but the two docs couldn't be more different. Should I trot out Roger Kahn again? You may glory in a team triumphant (“More Than a Game”) but you fall in love with a team in defeat (“Hoop Dreams”). What stopped William Gates in “Hoop Dreams”—injuries—isn’t even an issue in “More Than a Game“—any more than a knee injury would be an issue to Superman. We glory in LeBron but he came from another planet. We also know how he ends (well), so we watch knowing the ultimate end, as we watch most Hollywood blockbusters knowing the ultimate end. “Hoop Dreams,” in comparison, is a small, indy character study. Gates and Agee? We don’t even know if they live.

”More Than a Game" skirts issues that might have proven interesting—including questions of race and religion at St. Vincent. Were any of the “fab four” Catholic in ninth grade? Were any in 12th grade? It also tries to exalt Coach Dru, who seems like a decent man, but whose halftime pep talks are hardly out of “Knute Rockne: All American.”

But it’s fun and it ends right. For 90 minutes we’ve watched these kids grow from not-bad “shooting stars” to incredibly talented, between-the-leg-dunking, on-the-verge-of-the-NBA superstars. At the very end, though, we see Dru coaching a new batch of kids. Sixth graders? Younger? They’re doing lay-up drills, and missing, and they’re small and clumsy, and that basketball is so big in their hands. And it begins again.

Monday October 19, 2009

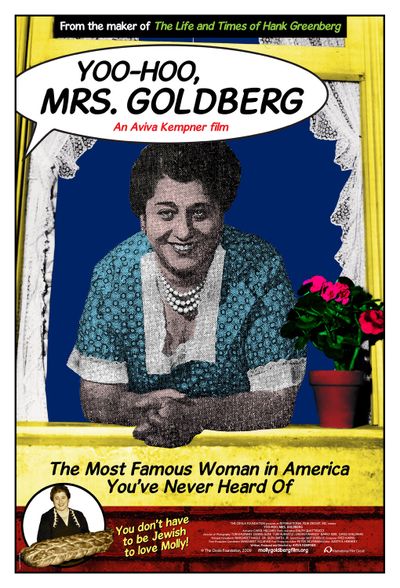

Review: “Yoo Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg” (2009)

YOO HOO! SPOILERS!

I’m a big fan of “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg,” documentarian Aviva Kempner’s unabashed love letter to the 1930s Detroit Tigers’ slugger, so I thought “Yoo Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg,” Ms. Kempner’s unabashed love letter to radio and television pioneer Gertrude Berg, “the Oprah of the 1930s,” would be right up my alley.

I left wondering if maybe Kempner wasn’t too close to a subject I knew too little about.

“The Goldbergs,” a daily radio show created by Berg (nee Tilly Edelstein) from old skits she performed at her father’s Catskills Mountain resort in Fleischmanns, NY, debuted on NBC radio the week after the October 1929 stock market crash. It concerned the comings and goings of a Jewish family—mother Molly (Berg), father Jake, children Sammy and Rosalie, and Uncle David—in a Lower East Side tenement, as they tried to both assimilate in America and not lose old world values.

Verisimilitude was big with Berg. She often visited the Lower East Side for ideas and dialogue, and out of this came Molly’s habit of calling up the airshafts to her neighbor: “Yoo hoo, Mrs. Bloo-oo-oom!” If Molly cooked eggs in her kitchen, Berg cooked eggs in the studio. During the Seder after Kristalnacht, a rock was thrown through the Goldbergs’ window. During World War II, families often referenced boys off fighting or relatives left behind in Nazi-occupied Europe.

Verisimilitude was big with Berg. She often visited the Lower East Side for ideas and dialogue, and out of this came Molly’s habit of calling up the airshafts to her neighbor: “Yoo hoo, Mrs. Bloo-oo-oom!” If Molly cooked eggs in her kitchen, Berg cooked eggs in the studio. During the Seder after Kristalnacht, a rock was thrown through the Goldbergs’ window. During World War II, families often referenced boys off fighting or relatives left behind in Nazi-occupied Europe.

It was a hit. The show became the second-most-popular show on the radio, after “Amos n’ Andy,” while Berg was voted the second-most-respected woman in America, after Eleanor Roosevelt. At the same time, the doc reminds us of the anti-Semitic touchstones of the period: Kristalnacht, Father Coughlin, bund rallies in Madison Square Garden.

This shouldn’t be a disconnect—Rush Limbaugh has the most popular radio show in an America that still elected Barack Obama—but it’s enough of one to raise questions. “The Goldbergs” was the second-most-popular show...in all of America? Including the South? What year or years? And what year or years was Berg voted the second-most-respected woman in America, and by whom?

Basically Kempner shows us this square peg but doesn’t tell us how it fit into the round hole of 1930s America. She posits “The Goldbergs” as unique—the first family sitcom; the only ethnic show where creative control was held by that ethnicity—but doesn’t tell us what it was unique against. I’m sorry but I'm blank on 1930s radio. The talking heads, mostly Jewish, mostly female, give a ton of love but not much perspective. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, for example, says everyone she knew growing up in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn listened to “The Goldbergs,” but that hardly feels like news. How did it do in Wisconsin? That’s what I want to know.

Eventually, the show was cancelled, in 1945, but was reborn in the new medium, television, on January 17, 1949. Was it the first TV sitcom? The first domestic TV sitcom? Did Berg introduce the nosy neighbor? That’s what people who love the show imply. Do we believe them? Ehh. By surrounding us with fans of the show, Kempner is actually shortchanging the show.

The episodes themselves, which ran live, are fascinating to see. Each began with Molly (Berg again) talking directly to the camera as to a neighbor, welcoming us in. “Greetings from our family to your family,” she says. She pitches corporate sponsor Sanka, and, via window-conversation with her neighbors, introduces the episode’s conflict. Then we go indoors and watch it all unfold.

But a conflict about the show—about America, really—turned out to be more compelling than any conflict on the show.

Broadway actor and union activist Philip Loeb, who played Molly’s husband, Jake, was one of the 151 entertainers listed in “Red Channels,” the 1950 anti-communist tract about supposed communist influence in the industry, and in Sept. 1950, General Foods, which sponsored “The Goldbergs,” told Berg, “You have two days to get rid of Philip Loeb.” Berg resisted, and the doc makes much of this resistance. But a few months later CBS cancelled “The Goldbergs.” When it returned, a year and a half later and on a different network, there was a new actor playing Jake. When he didn’t work out, a third actor replaced him. Three years, later, as “The Goldbergs” wound up its run, being filmed now rather than performed live, and with the family assimilated in the Connecticut suburbs rather than struggling on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Loeb took his own life in a New York hotel room. Twenty years later, he became the inspiration for Zero Mostel’s Hecky Brown in “The Front.”

These revelations are so stunning—to me anyway, a longtime fan of “The Front”—that they almost upend the documentary. One wonders: Should this have been the focus of the doc? Should “Red Channels”?

It doesn’t help that Berg, so innovative in the industry, hardly seems present in her own story. What do we learn about her? She dressed nice. Her father disapproved of her work and her mother wound up in a mental institution. She was a workaholic. But how she felt about Loeb? How she felt about anything? Who knows? There doesn’t seem to be much there there.

In terms of tone and structure, “Yoo Hoo, Mrs. Goldberg” is similar to “The Life and Times of Hank Greenberg," but it shouldn’t be. There was no Philip Loeb to sour Greenberg’s story. And if Greenberg’s personality wasn’t exactly dazzling, well, he was a ballplayer. He wasn't supposed to have personality. Besides, you still walked away from the doc with a sense you knew him. Not so with Berg.

Most important, Hank Greenberg is forever—people who know baseball will always know his name—but Gertrude Berg is not. That, in fact, is the doc’s raison d’etre: “The Most Famous Woman in America You've Never Heard Of,” reads the tagline. So why did Berg fade while contemporaries, such as Jack Benny and George Burns, did not? Were they funnier? More talented? More male? Less Jewish? It should be the doc’s main question yet it’s hardly asked at all.

Love letters are well and fine; but this one could’ve used a little more letter, a little less love.

Tuesday October 13, 2009

Review: A Serious Man (2009)

WARNING: SPOILERS

For most of my adult life, I’ve been told I'm fairly Jewish for a gentile kid from Minnesota. I blame the usual suspects: Roth, Doctorow, Mailer, Bellow, the Marx Bros., Woody Allen, Seinfeld.

Friday night, halfway through the Coen brothers new film, “A Serious Man,” I had the following epiphany: I have no fucking clue.

First they get all Hebrew on my ass. A gett? Hashem? Haftorah? Shabbos? Then they go Old Testament. “Actions have consequences,” Prof. Larry Gopnik (Michael Stuhlbarg) tells Clive (David Kang), a Korean foreign-exchange student attempting to bribe him to get a better grade. “Yes, often,” Clive quickly agrees. “Always,” Gopnik tells him.

Don’t even get me started on the prologue with the dybbuk.

The prologue with the dybbuk

It’s 1967 and Gopnik is a professor of physics who teaches the uncertainty principle and then lives it when his wife asks for a divorce, a ritual Jewish divorce, or gett, so she can remarry within her faith.  To Sy Abelman (Fred Melamed). “Sy Abelman?” Larry asks incredulously. He seems more perplexed for her reasons than her actions. So are we when we finally meet Sy. He’s bald and bearded, hardly Gregory Peck, but he’s controlling in a moist, maternal way—he’s forever hugging Larry—rather than being controlled by, as Larry often is.

To Sy Abelman (Fred Melamed). “Sy Abelman?” Larry asks incredulously. He seems more perplexed for her reasons than her actions. So are we when we finally meet Sy. He’s bald and bearded, hardly Gregory Peck, but he’s controlling in a moist, maternal way—he’s forever hugging Larry—rather than being controlled by, as Larry often is.

Gopnik is the kind of man who timidly obsesses over small details—such as the property line with the Brandts, his stoic, hunting-happy Minnesota neighbors—and misses the big picture. Not only is his wife leaving him but his kids have left him. His son, Danny, is a mess of sixties contradictions: he has that classic Beatles haircut (redhaired version), smokes pot, listens to Jefferson Airplane, but only cares to talk with his father when the reception for “F Troop,” the lamest of ‘60s sitcoms, comes in fuzzy. His daughter, Sarah, only talks to her father to complain about Uncle Arthur, Larry’s brother, hogging the bathroom to drain the cyst in his neck. When Larry gets banished from the marital bed, Arthur is the reason he doesn’t even get the couch in his own home—Arthur’s already there—he gets a cot next to the couch. Everyone wants something from Larry but never Larry. “We should wait,” he says at the dinner table when Uncle Arthur hasn’t arrived yet. “Are you kidding?” Danny responds and everyone starts in. Soon Larry is the one they don’t wait for. He and Arthur have been banished to The Jolly Roger, a nearby moto-lodge.

That’s at home. At work he’s being considered for tenure but letters arrive denigrating him. Dick Dutton from the Columbia Record Club, that great ‘60s scam, keeps calling abut money he owes. Then Clive’s father shows up accusing Larry of 1) defamation, because Larry accused his son of a bribe, and then pleading 2) cultural differences, because Larry didn’t accept the bribe.

Larry’s helpless before this kind of illogic. He can’t extricate himself from it. Life has the quality of a nightmare: Everything’s repetitive—Sy keeps hugging him, the Brandts keep playing catch, Arthur keeps draining his cyst—and everything’s unknowable. Dream sequences in other films are usually easy-to-spot but in the Coens’ films they blend almost seamlessly with life, so we in the audience are in the position of the dreamer: We don’t know what’s dream until it’s over. And even then. By the pool last night—did that happen?

Once Larry establishes that nothing is established—that everything he thought was one way is another—the film can be divided into three parts, or three solutions to this dilemma, based upon the three rabbis he visits at his temple, the “well of tradition” he tries to draw from.

The first, and youngest rabbi, is Rabbi Scott (Simon Helberg), who counsels seeing everything—everything—as an expression of God’s will. To see it all anew. This is the closest of the three to a Christian vision of life. “Look at the parking lot, Larry!” Rabbi Scott announces proudly, peeking through his horizontal blinds at the asphalt outside. Larry tries to carry this Pollyannaish mood to the office of his divorce lawyer (Adam Arkin), who looks at him as if he’s crazy. Then during the meeting he gets an emergency phone call from his son. What’s wrong, Danny? That pipsqueak voice: “F-Troop” is fuzzy again, Dad. How can we look at life anew when it’s so repetitive? This section ends when Larry gets into a fender-bender after cursing out Clive on his bicycle, while, at the same time, Sy, trying to make a left turn into a goyisher country club, dies in a car accident. Actions have consequences. Always.

The second, middle-aged rabbi, is Rabbi Nachtner (George Wyner), who tells Larry stories that at least seem headed toward the direction of eternal questions. He tells about the goy’s teeth, for example, a story about a dentist, Dr. Sussman, who, after making a mould for Russell Kraus, finds the phrase, ‘Help me, Save me,’ in Hebrew on the back of his incisors. He searches other people’s mouths for messages and gets nothing. He translates the letters into numbers and gets nowhere. And the Rabbi sits back, pleased with his story. Gopnik’s confused. “What did you tell Sussman?” Gopnik asks. “Sussman?” the rabbi answers. “Is it relevant?” “What happened to the goy?” Gopnik asks. “The goy?” the rabbi answers. “Who cares?” Told that you can’t know everything, Gopnik finally loses it. “Sounds like you don’t know anything,” he says, voice rising.

At this stage, more of life becomes unknowable. Detectives come looking for Uncle Arthur, for gambling. Cops bring home Uncle Arthur, charged with sodomy. Gopnik suspects his wife of draining their bank account. He gets high with his sexy neighbor, whom he’d seen nude-sunbathing from his roof. An old lawyer, about to reveal the secret to the Brandts’ property line, suddenly drops dead of a heart attack. “I am not an evil man!” he tells a colleague. “I’ve tried to be a serious man,” he tells the world. And there’s our title. We first heard it used to describe Sy Abelman at his funeral. A serious man. An able man. As opposed to a Gopnik? What is Larry’s crime? Not to God but to the Coens—who are, admittedly, the gods of this universe. Is it the foolishness of the assumption that good fortune follows good deeds, and thus bad fortune must follow bad deeds, and yet—he keeps asking himself—what bad deeds? Is it the foolishness of the “Why me?” question, when the universe, if it could answer, would simply answer, “Why not you?”

The final rabbi, the eldest and wisest and most difficult to see, is Rabbi Marshak (Alan Mandell), and Gopnik isn’t allowed to see him. He’s as silent to Gopnik as God is. But we get to see him. After his bar mitzvah, Danny, still stoned, visits Marshak, who, slowly, Yiddishly, delivers this pearl of wisdom:

When the truth is found to be lies

And all the joy within you dies

The boy smiles, recognizing the Jefferson Airplane’s “Somebody to Love,” which the rabbi first heard after Danny’s transistor radio was taken from him at the beginning of the film. “Be a good boy,” the rabbi finally says. Is this doddering wisdom or ultimate wisdom?

Who knows? There’s a scene early in the movie where Larry ascends the roof of his ranch-style house to fix the antenna so Danny can watch “F-Troop,” and he checks out the view over the other, ranch-style homes in this flat Minnesota neighborhood. It’s the shot on the poster, in which Larry looks decisive. He’s less so in the movie: all dress shoes and highwaters on a slanted roof, and the view isn’t exactly revelatory. Until he sees his neighbor, nude-sunbathing, and forgets everything else. That antenna on his roof only picks up so much—now this channel but not that channel—and all of us are pretty much the same: We only receive so much, and usually we go for “F-Troop” or get distracted by the nude sunbather. There’s an old proverb—“Man thinks, God laughs”—and much of the Coens’ work feels built upon this proverb. Their characters are helpless trying to fathom it all.

A lake from 1967

Give the Coens this: They get the details right. I was born in Minnesota in 1963 and seeing this film gave me flashbacks. I got as dizzy as Gopnik got on his roof looking at his nude neighbor. Mr. Brandt, the detective, the cop: they all have these classic, bland, Harmon Killebrew-type Minnesota faces from the period. The burnt orange Larry’s sexy neighbor wears is the exact right burnt orange for the coming age of Aquarius. The iced-tea glass she gives Gopnik is the exact right iced-tea glass. There’s a scene at a lake, Uncle Arthur at a neighborhood lake, and Gopnik on the shore complaining to a friend that he doesn’t deserve the miseries that are being visited upon him, and even that lake, somehow, feels exactly like a lake in 1967. I don’t know how they did that. The iced-tea glasses I can see; they can be manufactured or bought at a Value Village. But where does one get a lake from 1967? Is it the clothes and the bathing suits people are wearing, the landscaping that was done, the angle of the light in which the DP chose to film it—like the light of a slightly faded photograph? Is it all of the above? Nothing the Coens do is frivolous and yet little of it makes sense.

The ending of “A Serious Man,” which is a film about unknowability, and which is written and directed by the brothers who gave us the uncertain end of “No Country for Old Men,” shouldn’t come as much of a surprise—although it will, I’m sure, lead to debate. It’s already led to the internal kind.

Gopnik, assured of tenure, seemingly back with his wife, and the father of a son who’s now a man, gets the bill for his brother’s criminal defense attorney, Ron Meshbesher—who is, in reality, one of the more famous criminal defense attorneys in Minnesota—and it’s exorbitant. And he thinks about the envelope full of Korean bribe-money still in his desk drawer and eyes Cliff’s grade in his gradebook. The weather’s turning. In Hebrew school, Danny and others are being led outside because of one of Minnesota’s numerous tornado warnings, but the rabbi has trouble unlocking the door to the shelter. And as Gopnik in his office changes Cliff’s grade from an F to a C-, Danny sees the dark tornado funnel heading their way. THE END.

My first reaction: Aw, crap.

My second reaction: OK, unknowability, uncertainty. Way to emphasize the point, boys.

Third reaction: Or maybe it’s the opposite. Actions have consequences—always—and this disaster is what Gopnik’s slight indiscretion has wrought. By accepting the bribe, changing the grade, he loses his son—and anyone else in the tornado’s path. It’s Old Testament, baby. It’s Malamadic. The problem with Gopnik isn’t that he assumes that good fortune follows good deeds; it’s that he doesn’t assume it enough. He doesn’t live his life by it.

Fourth reaction: Or is the tornado metaphoric? Gopnik is feeling settled again in his life in suburban Minnesota in 1967 but there’s a tornado coming his way and our way: the rest of the sixties. A tornado that will upend everything.

Final reaction: I think, the Coens laugh.

Thursday October 08, 2009

Review of “Bright Star” (2009)

WARNING: ODE TO SPOILERS

The Uptown Theater in Seattle’s lower Queen Anne neighborhood unintentionally helped its audience empathize with John Keats (Ben Whishaw), the doomed protagonist in Jane Campion’s “Bright Star,” during its first show the other afternoon. As Keats coughed from tuberculosis, shivered in the rain and fled to the warmer weather of Naples and Rome, we in the audience sat for two hours in the cold, seemingly unheated theater. By the time Keats succumbed, we were chilled to the bone. Right there with ya, bro.

“Bright Star” is a lovely film about doomed love told at a leisurely pace, which raises—at least in me—the following questions: Does love need lethargy to bloom? Does it inspire lethargy? If you’re deeply in love, what else do you want or need besides your love? What do you pursue? The world is too much reduced. Maybe in this sense all young loves are doomed. We either lose the love or lose the world.

The key to “Bright Star,” though, as with all love stories, is less the love than the forces that keep the lovers apart.

The key to “Bright Star,” though, as with all love stories, is less the love than the forces that keep the lovers apart.

Initially young Fanny Brawne (Abbie Cornish), expert seamstress, and John Keats, failed poet, roundly savaged by the critics of his day, are strangers in Hamstead Village, London, 1818. They meet, talk of wit, talk of fashion, become intrigued. His brother dies, she sympathizes. She’s headstrong, as are all cinematic heroines during this period, and she buys and reads his book of poems, Endymion, which begins:

A thing of beauty is a joy for ever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness; but still will keep

A bower quiet for us, and a sleep

Full of sweet dreams, and health, and quiet breathing.

Nice thought! She doesn’t quite know what to make of it. “Are you frightened to speak truthfully?” he asks. “Never,” she replies, headstrong. Then she confesses she doesn’t really know poetry. He confesses he doesn’t really know women. They solve their mutual dilemma by having him teach her poetry.

The main aesthetic principle attributed to Keats is negative capability, “when man,“ he once wrote, ”is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” Shakespeare was the master, he felt, and in the film he describes the principle to Fanny via metaphor. Why do you dive into a lake? To swim to the other side? No. It’s for the experience of being surrounded by water. And that’s what poetry is.

These lessons take place over the protestations of his housemate and contemporary, Charles Armitage Brown (Paul Schneider), who, either from pettiness, jealousy, or genuine worry that Fanny will distract the great man, is one of the forces trying to keep them apart. He has the equally thankless role of playing Salieri to Keats’ Amadeus: the contemporary who recognizes the unrecognized genius and knows he’ll never measure up. Plus he chases after dull maids and knocks them up. Dude's a piece of work.

But there's a greater force keeping them apart: He’s a poet whose books don’t sell. He has no means of support.

Still, despite the mores of the time, they fall in love. Her family—mother, gawky silent younger brother, cute button of a red-haired baby sister—move into the duplex Keats and Brown share, where Fanny and Keats now have nothing but a wall separating them. Sometimes, rarely at the same time, they press their faces against this wall. It's the physical representation of all those forces keeping them apart.

These forces are no match for Spring. The weather warms, the bees flit around the flowers, and Mrs. Brawne says, “Mr. Keats is being a bee.” Indeed. He and Fanny go for a walk, and he tells her of a dream and talks of lips. “Whose lips?” she asks teasingly. “Were they my lips?” They kiss. The kiss comes as a shock. We get that? They get that? The film, quiet anyway, drops to murmurs. The music overwhelms. Is it Mozart? Baby sister fetches them and they play a game on the way back, freezing in their tracks when she turns around. Fanny lays on her bed, the breeze billowing the curtains. Life is suspended and buzzing. It’s opened up—all senses—but reduced to the next walk, hand hold, glance. Campion is close to brilliant here. Her film isn’t just about first love; it feels like first love.

But being in love is never the story. So Keats travels to the Isle of Wight to write, to try to make a living, and Fanny is left behind. Ah, but the letters. He writes, says he wishes they could be butterflies, living three perfect summer days and expiring, and she and her siblings collect butterflies and fill her room. “When I don’t hear from him,” she confesses to her mother, “it’s as if I’d die.” One can't help but remember one's own first love. Mine took place in the late 1980s, and, though 170 years had passed, the means of communication, give or take a telephone, were more or less the same. Twenty years later, they're not. Do young lovers today still send letters? How does one clutch an e-mail to one’s chest? There is no more daily waiting for the postman. Now the wait is 24/7. Has she written? Has she written? Has she written? I think I’d go crazy. Or crazier.

When the Isle of Wight doesn’t change his fortunes, Keats seeks them in London, and the dead butterflies are swept up. But he keeps returning in all kinds of weather. Does anyone go to “Bright Star” not knowing Keats’ end? Watching, I kept thinking of that Seymour Glass poem from J.D. Salinger’s “Seymour: An Introduction”:

John Keats

John Keats

John

Please put your scarf on

When Brown says, “Mr. Keats has gone to London with no coat,” I knew this was it. But even death is drawn out in the 19th century.

My disappointment with the film is in its end, dealing, as it does, with the pain of those left behind and not with the mystery of the final barrier. Does Keats have his face pressed to that wall or is he dissolved like the butterflies? The film should’ve dove into those mysteries, surrounded us with them. What happened to him and her and their love? Did it pass into nothingness or is it a joy forever? Or am I irritably clutching after?

“Bright Star” is a wholly evocative film. See it not to find out what happens. See it for the sensation of surrounding yourself with it.

Monday October 05, 2009

Review: “The Invention of Lying” (2009)

WARNING: JUST-THE-FACTS SPOILERS

The big problem with Ricky Gervais’ comedy “The Invention of Lying” is this: Lying isn’t funny. The truth is funny. Uncomfortable truths. Blunt truths. It’s funny—in this universe where people haven’t yet developed the gene to lie—when Anna McDoogles (Jennifer Garner) greets Mark Bellison (Gervais) at the door by admitting she’d just been masturbating and he responds, helplessly, “That makes me think of your vagina.” It’s funny when she tells her mother, who phones during their date, and within earshot of Mark, “No, I won’t be sleeping with him.” It’s particularly funny, because it’s particularly uncomfortable, when the old folks’ home is named: “A Sad Place for Hopeless Old People.”

But saying to a bank teller that you’ve got $800 in your account when you have $300, or telling a cop that your friend isn’t drunk when he is, or even telling your scared, dying mother that there’s a beautiful place we go when we die—all of which happens after Mark develops the gene for lying—none of that is particularly funny. It’s sometimes poignant, and certainly ballsy, but it isn’t funny. Thus the movement of the film is from funny to less funny. By the end, there’s hardly any laughs at all.

“The Invention of Lying” is basically a magic realism film like “Liar, Liar,” and “What Women Want,” where an extraordinary thing happens to an ordinary man. Here the extraordinary thing—being able to lie—makes Mark more like us rather than less. He’s also a nicer guy than the main characters of those two films. The extraordinary thing happens to Jim Carrey and Mel Gibson so each will become a better man. It’s the “Christmas Carol” pattern: 1) jerk; 2) extraordinary thing; 3) OK dude.

“The Invention of Lying” is basically a magic realism film like “Liar, Liar,” and “What Women Want,” where an extraordinary thing happens to an ordinary man. Here the extraordinary thing—being able to lie—makes Mark more like us rather than less. He’s also a nicer guy than the main characters of those two films. The extraordinary thing happens to Jim Carrey and Mel Gibson so each will become a better man. It’s the “Christmas Carol” pattern: 1) jerk; 2) extraordinary thing; 3) OK dude.

Not here. Mark is actually a decent sort. Sure, he lies his way to riches, and, yes, initially he almost lies his way into bed with a beautiful woman, but at the last instant, because he’s a decent sort, he backs out. (Every guy in the audience is going, “Nooooooooo!”) Then he immediately does good deeds. He doesn’t wait for the third act. He steals money for a homeless man. He helps a bickering couple. He stops a neighbor from killing himself. And, yes, as his mother trembles at the prospect of dying, of not existing, he invents...heaven. So she can die happy. If anything, he’s trying to make the rest of the world as decent as he is.

There’s audacity in this. In a world without lying, there isn’t religion, there isn’t God. It’s up to Mark, pressed into service after word of “heaven” spreads, to invent these things. So he invents the Man in the Sky, and the Good and the Bad Place, and he tells everyone that if the Man in the Sky sends them to the Good Place they will get a mansion. Since people can’t even fathom the concept of lying, everyone takes everything he says as fact. One wonders why it doesn’t lead to a rash of suicides. We don’t have them because we have doubt, and, for true believers, suicide is against God’s will. But what’s to stop these folks? The undiscovered country is not only discovered, it’s mapped.

This element of the film, yes, is audacious, but everything else feels small and predictable. Why are magic realism films always like this? Mel Gibson can read women’s thoughts and he uses the power...to create a better ad campaign? Ricky Gervais can lie in a world where no one else can and he uses the power...to get his old job back? He’s a screenwriter for Lecture Films, which is exactly what it says it is. Films in this world consist of professorial lecturers sitting in armchairs and reading history to the camera. Mark has been stuck with the 13th century, which doesn’t exactly lend itself to exciting storytelling. But with his newfound power he creates a screenplay about aliens and adventures that everyone takes—must take—as fact, and reduces people to tears. It’s called “The Black Plague” and it’s a big hit and wins awards, but, beyond the insider-Hollywood stuff, what’s the point? He’s the most powerful man in the world! Whatever he says is fact because there’s no concept of non-fact. “I’m your husband.” “That’s my house.” “I’m the president of the United States.” Rob Lowe plays his nemesis? Mark could reduce him to nothing. “He’s been fired.” “He’s been evicted.” “He wants his head shaved.” Instead Mark suffers his presence throughout the film.

Worse, the film becomes about the most conventional of conventional tropes: getting-the-girl.

Anna (Garner) eventually comes to love Mark for his unconventionality but can’t bear the thought of having kids with him because they might look like him: i.e., fat, with snub noses. She wants a better genetic partner. Everyone does. Everyone is shallow in this world. Everyone goes out of their way to say the meanest things. Admittedly we are a rude, shallow species but is that all we are? I’m running through my day, thinking about what I’d say not only if I couldn’t lie, but, as here, and as in “Liar, Liar,” if I felt compelled to say every truthful thing that came into my head. So, yes, there’d be “Man, you’re annoying,” “God, you talk a lot,” “My, I’d like to sleep with you.” But there'd also be: “Man, you’re smart,” “God, you’re fun to be with,” “My, I’d like to sleep with you.” I don’t think we’re as bad as Gervais implies.

Critics are already setting up in knee-jerk camps. Kyle Smith of The New York Post says the film takes “outspoken atheism” and “dump[s] it all over an unsuspecting audience,” while hipster critics dig its attack on organized religion. But its greater attack is on human nature. In the world according to Gervais, the truth doesn’t set us free; it makes us jerks. Meanwhile, lies—including religion—make us better people. The film might as well be called “The Invention of Decency.”

There are some impressive cameos here: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Ed Norton, Jason Bateman. (We also had Jeff Bezos in the audience at the Regal Meridian in downtown Seattle.) But the film is too conventional for its unconventional premise, while its unconventional premise goes against the grain of what's funny. The truth may not set us free, but it does make us laugh.

Monday September 28, 2009

Review: “'Surrogates” (2009)

WARNING: LUDDITE SPOILERS

At first “Surrogates” didn’t look like much to me, particularly when I saw those online ads of sexy women with exposed robot parts. Then I read some synopses and became intrigued by the premise. Then I went to see it.

Trust your first instincts.

In the near-future, near-perfect robots, attuned to individual brain patterns, are created initially so the handicapped can move around more easily; then they're used in place of soldiers in time of war; then, well, because it’s fun and easy. You lay in a chair at home and feel whatever your better-looking, stronger surrogate is doing out in the world. You experience life virtually. All the fears you may have of the outside world—death, germs, stubbed toes—are gone.

In the near-future, near-perfect robots, attuned to individual brain patterns, are created initially so the handicapped can move around more easily; then they're used in place of soldiers in time of war; then, well, because it’s fun and easy. You lay in a chair at home and feel whatever your better-looking, stronger surrogate is doing out in the world. You experience life virtually. All the fears you may have of the outside world—death, germs, stubbed toes—are gone.

So it’s kind of like TV. It’s kind of like this thing. It’s kind of like video games and avatars and fill in the blank.

It’s relevant.

Strike that. Should be relevant. The movie is ultimately hugely naive about human nature.

During the titles, we get the 14-year history of surrogates. How they were created by a wheelchair-bound man named Canter (James Crowell: uh oh!), and how the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of surrogates “in daily life” (making “with all deliberate speed” sound like the most precise language possible), and how the conglomerate VSI became the leading manufacturer of surrogates, but how seven years ago they had a falling out with Canter, and three years ago an anti-surrogate movement began, led by a man named The Prophet (Ving Rhames in Rastafarian wig), and “surrogate-free zones” were created in major American cities like Boston.

The story proper begins in the back of a limousine, where the son of Canter (in surrogate form) heads to a club, meets a beautiful blonde, makes out with her in an alleyway, and is then killed by a sinister guy on a motorcycle.

Because the surrogate revolution led to a 99 percent drop in crime, this is an unprecedented homicide, and surrogate FBI agents arrive: Greer (Bruce Willis, with blonde hair and wrinkle-less face) and Peters (Radha Mitchell, looking like herself). They quickly find out that the beautiful blonde was surrogate to a fat bald man—nice touch—and his safety wall has been breached: He's dead in his chair at home. So is Canter. Then everyone clams up fast. The FBI chief, Stone (Boris Kodjoe), imposes a total media blackout, Canter is distraught and enigmatic, the folks at VMI toe the company line.

Greer plays good cop with Canter, bad cop with the lawyers at VSI. “I hate lawyers,” he says. But he’s friends with the agency tech geek, who, in a crushingly obvious plot device, has access to every surrogate/operator in the world. That’s basically the gun in the first act, isn’t it? And yes, it goes off.

Through the tech geek, Canter learns the killer’s name (Strickland) and whereabouts. Surrogate cops go after him, surrogate cops drop—as do their operators. Greer almost gets it, too, but crashlands in a surrogate-free zone. Even as he pursues Strickland, he’s pursed by a hillbillyish mob, who, just as he’s about to get Strickland, get him. They crucify him—the surrogate—as a warning to all surrogates.

Questions at this point in the story:

- Why would surrogacy lead to a 99 percent drop in crime? If surrogacy is similar to going online, wouldn’t we be even less civil as surrogates? Wouldn’t it be easier to fight and kill, because it wouldn't really have consequences? The behavior the filmmakers foresee is the exact opposite of the behavior likely to occur.

- If your surrogate doesn’t have to look like you—as seems to be the case—does this mean a million Angelina Jolieish girls are walking around—as in the poster? Wouldn’t this be confusing? How about a million Batmen?

- Why are all of the luddites, the “dreads,” fat and ugly? Wouldn’t these be among the first people to embrace surrogacy?

- The surrogates have a blanched, creepy look because the film is ultimately anti-surrogacy. It’s supposed to make surrogates less appealing to us in the audience, but it doesn’t answer the question of why surrogates are appealing within the movie. And surely there are kids in this future, ironic hipsters, who would want an old/fat/ugly surrogate? Just to thumb their noses at the rest of society?

- Why do the posters of The Prophet, with LIVE printed below, remind me of the Obama HOPE poster? Is this another right-wing message from the right-wing folks in Hollywood?

- With all the looks in all of the world to choose from, how did surrogate Bruce Willis wind up with that hair?

In the wake of the mob crucifixion, the real Greer—bald, wrinkled, goateed—is momentarily surrogateless and taking baby steps in the world again, but there’s a half-heartedness to him. He’s father to a son who was killed (baseball glove and Red Sox posters fill his still-pristine room), and husband to a wife who relies on her surrogate to get through her day. In fact, he seems more interested in connecting with his wife than in connecting-the-dots of the case. He’s more interested in making the filmmakers’ case (surrogacy sucks!) than his own.

Maybe because the criminal case isn’t that interesting? Three villains to choose from: Canter, VSI, Stone. Who’s guilty? All of them. VSI invented the weapon that breached the safety wall but tried to hide it, Stone has been promised a cushy gig at VSI if he can bring it back, but it’s in the hands of Canter, who, sickened by what he’s created, wants to undo his Frankenstein monster by killing its billion operators. He’s even behind the whole “dreads” movement, whose Prophet is actually a surrogate, controlled by Canter. Question: Wouldn’t Canter himself have made a better prophet than his Prophet? Wouldn’t he have immediate authority in the matter?

In the end Canter kills Peters and controls her surrogate to breach the room where the tech geek has access to all surrogates and operators, so he can kill them all. “They were dead the day they plugged in,” he snarls. Greer tries to stop the countdown and we get the following exciting dialogue from the handcuffed tech-geek: “Hit enter! No, wait! Shift enter!” Is this what all of our action movies are going to sound like now? “Control-alt-delete, motherfucker! Oh shit, you’re on a Mac keyboard? Command-option-escape! No, the command key is the one with the apple on it! With the apple on iiiiiitt!”

One of the saddest moments I’ve experienced at a movie this year came at the end of “Surrogates,” when Greer, given the option to reconnect or disconnect operators around the world, chooses disconnect, and a billion surrogates—and planes, trains, automobiles?—drop to the ground. In the theater someone actually applauded—so loudly and insistently I wondered if he wasn’t a marketing plant. If he wasn’t, more's the pity.

Why was he applauding? Because Greer defeated not only the bad guys but the concept of surrogacy. Operators—that is, us—came out of their homes, blinked, and looked around. It was a new day. But it wasn’t. If anything the scene reminded me of a power outage, when everyone suddenly leaves their homes and mingles with their neighbors...until the power is restored. Then they return to whatever surrogate life they were living: TV, Internet, video games. The same would’ve happened in the movie. Power outages do not change human nature. The filmmakers want the ending to be uplifting when they know it’s not.

Here’s the sadder part. Why was this guy really applauding? Because his surrogate for the last 90 minutes, the actor Bruce Willis, defeated the concept of surrogates in this movie he was watching. That’s the disconnect, isn’t it? That’s the lie the filmmakers are smoothing over as expertly as VSI smooths over its lies. That's why the best lines of the movie are the first lines of the movie: Ving Rhames' contemptuous voice against a dark screen: “Look at yourselves. Unplug from your chairs and get up and look at how God made you.” Not only you, the operators in the movie, but you, the audience watching the movie. Unplug yourselves.

No one did.

Monday September 21, 2009

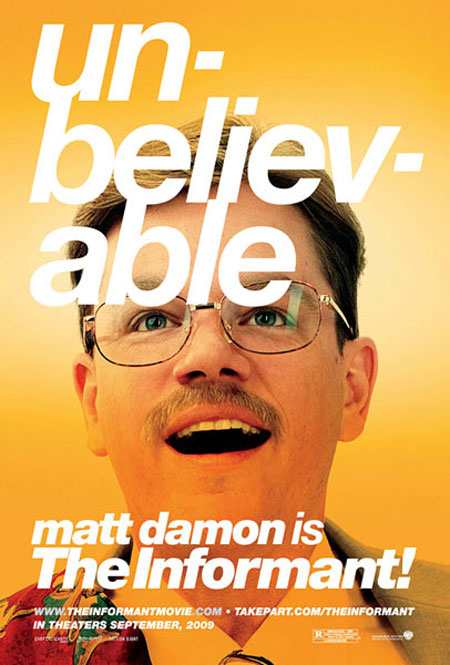

Review: “The Informant!” (2009)

WARNING: SPOILERS LACED WITH LYSINE AND GLUCONATE

“The Informant!” is a movie set in the 1990s but designed for the 2000s—with title graphics from the late 1960s and a soundtrack from...the 1950s? When were kazoos popular? It has, in other words, a real chance to be a cult hit. It’s probably too quirky to be popular. It’s too original.

Matt Damon, looking as horribly ordinary as movie stars are allowed to look, plays Mark Whitacre, a vice-president at Archer-Daniels-Midland (ADM), a conglomerate based in Decatur, Ill., and, if memory serves, a company that perennially supports PBS public affairs programming. But its main business is taking cereal grains and oilseeds and putting them into food and feed.

As the film opens, there’s a virus eating both the lysine in the ADM plants and the profits that the conglomerate demands, and Whitacre’s getting the blame from the son of the boss, Mick Andreas (Tom Papa), for not solving the problem. It’s amusing but unfair—in the way that sons-of-bosses always seem amusing but unfair. Then Whitacre gets a call from a Japanese colleague who says an ADM mole is responsible for the virus and he’ll reveal the name for $10 million. Rather than pay off, though, the higher-ups at ADM bring in the FBI, who tap Whitacre’s personal line to find out more. This bothers Whitacre—first a little, then a lot—and, with his wife’s prodding, he reveals to FBI agent Brian Shepard (Scott Bakula), that ADM and the Japanese are involved in price-fixing the international lysine market. Which is how Whitacre turns informant. “Mark, why are you doing this?" Shepard asks at one point. “Because things are going on that I don’t approve of,” he says. “They’re making me lie to people.”

As the film opens, there’s a virus eating both the lysine in the ADM plants and the profits that the conglomerate demands, and Whitacre’s getting the blame from the son of the boss, Mick Andreas (Tom Papa), for not solving the problem. It’s amusing but unfair—in the way that sons-of-bosses always seem amusing but unfair. Then Whitacre gets a call from a Japanese colleague who says an ADM mole is responsible for the virus and he’ll reveal the name for $10 million. Rather than pay off, though, the higher-ups at ADM bring in the FBI, who tap Whitacre’s personal line to find out more. This bothers Whitacre—first a little, then a lot—and, with his wife’s prodding, he reveals to FBI agent Brian Shepard (Scott Bakula), that ADM and the Japanese are involved in price-fixing the international lysine market. Which is how Whitacre turns informant. “Mark, why are you doing this?" Shepard asks at one point. “Because things are going on that I don’t approve of,” he says. “They’re making me lie to people.”

Hold that thought.

Whitacre is obviously a bit of a joke. He's dumpy with an out-of-date moustache, yet “secret agent” music plays as he drives up to his house or to his office, as if that's how he sees himself. When he’s wired he provides a running commentary on his day, and greets everyone by full name and occupation: “Good morning Liz Taylor, secretary.” At one point he calls himself 0014 because “I’m twice as smart as James Bond.” He ain’t dumb—at one point, a Japanese businessman blocks the FBI’s hidden camera, and Whitacre deftly gets him to move, and then deftly gets everyone in the room, the price fixers, to say the magic word: “agree”—but there’s something off about him.

He’s our narrator, too, providing a running commentary on...what exactly? He gives us asides, trivia, tidbits of information. Initially these asides have something to do with the action—all the corn, for example, that ADM puts into its products, our products, and how they use corn and chemicals to bring chickens to maturity in a fraction of the time that nature intended—but soon he’s talking about Central American butterflies, and how he likes an indoor swimming pool for its “year-round usage,” and how he thinks his hands are his best feature. I could see the movie again just for these asides.

He also keeps shifting his position. After his initial confession to the FBI he avoids its agents, insisting that the virus is gone and the price-fixing is over and can't they just leave him alone? Then he has delusions about what will happen after the big reveal. “How can you possibly stay [at ADM] when you’ve just taken down the company?” his wife, faithful to a fault, asks. “Because they need me to run the company,” he insists. There’s a logic there that manages to ignore the entirety of human nature. It’s a void so large one doesn’t know what to make of it.

Throughout we think we’re in on it but we're not. That's the true beauty of the film. After the big reveal, we get a lot of little reveals, and Whitacre, who has kept his secrets for so long, can’t shut up. Everyone tells him not to say anything and he says everything. He tells other ADM employees about the FBI raid before it happens. Once it happens he talks to lawyer 1, lawyer 2, The Wall Street Journal. He’s been outed as a rat and merely says, “Did you see my stipple portrait? Pretty good.”

The second big reveal comes from an internal ADM investigation into Whitacre. While he’s been informing for the FBI he’s also been taking kickbacks—leaving his agents open-mouthed and the agency shifting its focus to him. First he denies everything. Then he blames the corporate culture. Then he says, “I only took a million and a half dollars.” This figure keeps rising. Seven million, nine million, eleven million. “But Mick knew about that!” he insists, as if that makes it OK. He blames a bipolar disorder—but doesn’t suffer from it. He takes refuge as an orphan—but isn’t one. He wears a toupee. Nothing about this guy is true. He may have been responsible for planting the lysine virus in the first place. And yet there’s no mea culpa. Even as he goes to prison, he’s still prevaricating. He’s still off. You get the feeling he doesn’t get what he's done wrong. He still sees himself the hero, the white hat, of his own movie, which is why he’s the perfect hero for this one.

Damon, by the way, is blissfully obtuse as Whitacre, and there’s a supporting cast to die for. At one point I wondered, “Is that the guy who played Biff Tanen in ‘Back to the Future’?” Later I realized, “No, it’s the guy who played the guard in ‘Shawshank.’” Later still I realized it was both actors, they’re both in it. Tom Smothers shows up as ADM’s CEO, Dick as a judge. Giants’ fan Patton Oswalt is in there, plus a Cusack sister, plus Candy Clark. Scott Bakula, as the main FBI agent on the case, is needy, dismissive, impressed and ultimately betrayed—the most ordinary FBI agent ever filmed.

Whitacre did his deeds in the nineties but he’s obviously a protagonist for our time. He lies and prevaricates and lies some more. One can’t even keep up with it all. One wonders, as with so many of our public figures, if he even knows who he is. There’s no there there. There’s not even there enough to care that there’s no there. It’s a tragedy, filmed as a comedy, and the tone is exactly right. Welcome back, Steven Soderbergh. Break out the kazoos.

Saturday September 05, 2009

Review: “The Cove” (2009)

WARNING: WHISTLING, CLICKING AND SCREECHING SPOILERS

Movies aren’t known for their great first sentences the way books are—for obvious reasons— but “The Cove” gives us a great first sentence. I forget if anything’s on the screen, or if it’s black, but you hear director Louie Psihoyos in voiceover:

“I do want to say that we tried to do the story legally.”

That story is relatively simple. Every year in Taiji, Japan, fishermen drive thousands of dolphins toward shore and into a cove, where the best are chosen for “Sea World” type shows around the world, and the rest are driven to a secret cove, where they are secretly slaughtered.

The hero of the story is Ric O’Barry, whom we get piecemeal. Each piece is fascinating. He was supposed to be the featured speaker at a conference on dolphins that Psihoyos was attending but got pulled because the sponsor of the conference, SeaWorld, wanted nothing to do with him. O’Barry’s an activist. He frees dolphins, including SeaWorld dolphins, in captivity. “How many times have you been arrested?” Psihoyos asks him. “This year?” O’Barry answers.

The hero of the story is Ric O’Barry, whom we get piecemeal. Each piece is fascinating. He was supposed to be the featured speaker at a conference on dolphins that Psihoyos was attending but got pulled because the sponsor of the conference, SeaWorld, wanted nothing to do with him. O’Barry’s an activist. He frees dolphins, including SeaWorld dolphins, in captivity. “How many times have you been arrested?” Psihoyos asks him. “This year?” O’Barry answers.

Eyebrows go up—mine did anyway—when you find out that O’Barry’s not just any activist; he was the original trainer on “Flipper,” the 1960s TV series that’s responsible, in part, for the popularity of dolphin shows at places like SeaWorld. The family’s house on “Flipper” was his house, and he guest-starred in one episode. In fact, he captured the five female dolphins who played Flipper.

Near the end of the series, though, one of the dolphins playing Flipper, Cathy, swam into his arms and killed herself. She just stopped breathing. The next day O’Barry was arrested trying to free a dolphin. He hasn’t stopped since.

He says their acoustic sense is so well-developed that the finest sonar in the world is nothing in comparison. Thus loud noises and enclosed areas—like at a Sea World show—are stressful. They get ulcers. They die. We capture them because we love them, then we give them what kills them. “The dolphin smile is nature’s greatest deception,” he says. “It creates the illusion they’re always happy.”

After they meet, O’Barry takes Psihoyos to Taiji, where O’Barry’s as known—and as wanted—as he is at SeaWorld. Authorities stake him out, watch him, question him through the fog of a foreign language. The brunt of the story’s here. The goal of the two men is to film the killing that goes on in the secret cove—to let the world know that it goes on—but it’s not easy. Local authorities harass them. Local fishermen harass them, including a particularly annoying and bespectacled man whom they dub “Private Space,” because that’s what he’s always yelling. The cove is surrounded on all three sides by high, private cliffs. There is no public vantage point from which to film. And they are harassed.

Great movies have been made about the assembling of a team—think “Asphalt Jungle,” “Dirty Dozen,” the first season of “The Wire”—and “The Cove” simply gives us the real-life version. Friends at George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic use their expertise to fashion faux-rocks around hidden cameras. Two of the world’s great freedivers join the team, along with a couple of dudes up for a good cause and an adrenaline rush. It's “Mission: Impossible.”

The question arises: Why are they killing the dolphins anyway? Not even the Japanese eat dolphin meat. Ah, but the Japanese are eating dolphin meat, unknowingly, because it’s often packaged as something else. The Taiji city council even proposes adding dolphin meat to the diet of all Japanese schoolchildren. This, too, is secret, but two councilmembers who have school-age children and know the dangers of eating such meat—with its high concentration of mercury—come forward and tell the tale. Most of the doc is like this. It’s about revealing what is secret and hidden. To do so, our heroes hide what reveals. At night, they trespass, swim into the cove at night, position the cameras (disguised as rocks) and leave. Then they wait for the killing to begin.

At its high point, in early August, “The Cove” played at 56 theaters in the U.S., but quickly fell off. It’s barely made over half a million dollars. Jeff Wells, a big proponent, suggests that part of the problem with this low turnout is that women who care about dolphins can’t bear to see a doc in which dolphins are slaughtered. That was exactly my experience. It opened in early August at the Egyptian, a mile from my home, but when I suggested it to Patricia—thinking she would leap at the chance—she turned it down cold. Said she couldn’t bear to see dolphins killed. Which is why I didn’t see it until a late weekday September afternoon, in a small theater at the Metro—about five miles from my home—with about four other people. Two days before it skipped town. It even skipped The Crest, the second-run theater in north Seattle that is currently showing the year’s big hit: “Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen.” At one point in “The Cove,” it's suggested that dolphins are not only smart, they’re actually smarter than us. Doesn’t seem that difficult.

A mammal that always smiles, with Ric O'Barry, who rarely does

So how bad is the killing? Most of it takes place underwater, so you don’t really see it. You hear the dolphins’ screeches—which, to my ears, doesn’t sound much different than their “happy” screeches—and you see the water turn red. And I’m not talking a little red. It’s like the scene in “The Ten Commandments” when Moses changes the Nile to blood. It’s Technicolor red.

Still, the most memorable scene to me, the one I took away, is footage of Mandy-Rae Cruikshank, the world class freediver, swimming with dolphins, and rubbing one on its belly, like it’s a dog or a cat, and the dolphin staying close, and luxuriating in the touch. In the wild. It’s remarkable.

Bottom line: “The Cove” is a good doc that’s doing good work. Apparently the dolphin killing in Taiji has stopped. At least for this year.

Tuesday September 01, 2009

Review: “Tyson” (2009)

WARNING: HEAVYWEIGHT SPOILERS

The most surprising admission in “Tyson,” James Toback’s documentary about former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson, isn’t that Tyson was scared heading into the ring, nor that he wanted women to protect him—him, the baddest man on the planet. It’s this: When he was young, Mike Tyson was Woody Allen.

The revelation comes early in the doc, which consists almost exclusively of old fight footage and present-day Tyson interviews. Tyson, bald now, Maori warrior tattoo sweeping one side of his face, and dressed in a pressed, button-down shirt and slacks in a Hollywood mansion, tries to explain who he is by explaning where he came from: the Brownesville section of Brooklyn, where, he says, it was “kill or be killed.” He talks about getting picked on. He talks about getting money stolen from him—quarters and change—by neighborhood gangs. Then he talks about how someone once took his glasses and broke them. The image that comes to mind is Virgil Starkwell forever having his glasses stomped on by bullies in “Take the Money and Run.” Mike Tyson was Woody Allen? Who knew?

A second later you narrow your eyes. Wait a minute. Glasses? Did Tyson need them as a kid? Did he stop needing them as an adult? You believe Tyson when he says, of the man who lived with his mother: “He might have been my father... I believe he was my father... I was told he was my father”— a sequence that Toback splices together to great echoing effect. But the glasses thing?

Or was he talking about sunglasses?

That’s part of the challenge of “Tyson.” How much do you buy into what he’s saying? When is he bullshitting us? When is he bullshitting himself? And when is James Toback putting too personal a stamp on Tyson’s story? Half the film is rise and half is sad fall, and Toback ends the first part with Tyson saying, “Once I’m in the ring, I’m a god. No one can beat me.” Then we get a slow fade and a slow open on Robin Givens. The implication is that everything began to go wrong with her, but, truly everything began to go wrong with the “god” comment and the hubris it represents. Pride, as always, goeth.

That’s part of the challenge of “Tyson.” How much do you buy into what he’s saying? When is he bullshitting us? When is he bullshitting himself? And when is James Toback putting too personal a stamp on Tyson’s story? Half the film is rise and half is sad fall, and Toback ends the first part with Tyson saying, “Once I’m in the ring, I’m a god. No one can beat me.” Then we get a slow fade and a slow open on Robin Givens. The implication is that everything began to go wrong with her, but, truly everything began to go wrong with the “god” comment and the hubris it represents. Pride, as always, goeth.

Tyson was trained by Cus D’Amato—who deserves his own doc, and who died in November 1985, a year before Tyson knocked out Trevor Berbick in the second round to become heavyweight champion of the world. Then he was trained by Kevin Rooney, but Tyson fired him in late 1988. He was managed by Jim Jacobs and Bill Cayton. But Jacobs died in March 1988 and Don King suddenly insinuated himself into the picture, fighting and apparently beating Cayton over Tyson’s contract. Why did Tyson go along with this? What part did racial politics play? And why doesn’t the doc focus on it more? Toback blames the lack of training, the partying, the women, but all of this is related to a larger issue: Tyson stopped dancing with those who brung him.

Tyson is surprisingly kind to Givens. He calls her “this young lady.” He says “everyone was in our business.” He says “We were just kids, just kids, just kids.” He doesn’t know why she lied to Barbara Walters on national television—Givens, with Tyson hanging over her shoulder, tells Barbara, and the country, that Mike, the heavyweight champion of the world, is a manic depressive, that their marriage has been pure hell, that “it’s been worse than anyone could imagine”—but in this doc he more or less gives her a bye.

Not so with others. “When I was falsely accused of raping that wretched swine of a woman, Desiree Washington, it was the most horrible moment in my life,” he says. He calls Don King “just a slimy, reptilian motherfucker” who would “kills his own mother for a dollar.”

He’s also hard on himself. He owns up to a lot. That he likes strong women whom he can sexually dominate. That when Cus D’Amato first takes him to his mansion, he’s thinking of robbing him: “I could rob this white guy,” he thinks.

He breaks down on camera talking about Cus. It seems the most important relationship in his life. At the same time he says, “I was like his dog. He broke me down. He broke me down and rebuilt me.” Cus also gave him speed, power, confidence. The doc is separated between those who built up Tyson’s confidence (D’Amato, mostly) and those who tore it down (Givens, Washington, King).

Remember how fierce he was? He had 15 fights in 1985 and won all of them by KO or TKO, 11 of them in the first round. He was built like a bullet and seemed just as unstoppable. He was so tough he inspired the toady in other men. Hell, I even felt it from afar, joking about his prowess in the ring, luxuriating in his power as if it were in any way related to my own (lack thereof). Or maybe I simply liked how much of a unifying concept he was in an increasingly fragmented world. He unified all the heavyweight belts that had been scattered to the four winds. For years no one argued over who the best boxer was. The only question was the question the announcer asked after Tyson destroyed Michael Spinks at 1:31 in the first round in a heavyweight bout in 1988: “Who in this world has any chance against this man?”

Himself. He was not a god. Gods don’t have to train, but he did, and he lost to Buster Douglas in 1990 in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. We kept waiting for him to unify things again but he kept stumbling. First the rape charge, then the conviction. He lost three years. When he came out of prison, he was a Muslim. This too seemed sad, like it was part of someone else’s story, as it was. It was Malcolm’s and Muhammed Ali’s. Tyson was clinging to cliches.

I’d forgotten that he won the heavyweight championship again in the mid-1990s. I didn’t know, in the infamous ear-biting match with Evander Holyfied, that Tyson claimed Holyfield headbutted him first. I’m not a boxing fan so I didn’t know. But I knew so much else because Tyson seeped through to the general culture in a way no boxer has since. Who’s even the heavyweight champ now? I had to look it up. A Russian and two Ukranian brothers. Three Great White Hopes. Scattered to the four winds.

“Tyson” is an untraditional doc in that there are no other talking heads. Would it have been better with other voices? Maybe. Would it have been better without Tyson walking along a Malibu beach? Yes. That Hollywood home, it turns out, was rented by Toback. So where does Tyson live? Why didn’t they film there? Why this fake Hollywood backdrop?

It’s still effective. The former champ seems lost in the way of former champs. “Old too soon, smart too late,” he says. “”What I’ve done in the past is a history, what I’ll do in the future is a mystery,” he says. The final shot is a freezeframe on his battered, confused face. He once thought himself a god. Now he’s just another man who can’t make sense of his life.

Monday August 31, 2009

Review: “District 9” (2009)

WARNING: OBVIOUS METAPHORIC SPOILERS

“District 9” is as stupid from the left as “Transformers 2” is from the right.

“Transformers 2” is about sleek, metallic aliens who ally themselves with the U.S. military, and, despite the meddling of a petty bureaucrat, help protect the planet. The aliens stand tall, talk bland, ring hollow. They’re glossy and soulless. They’re basically metaphors for weaponry. That’s why the film feels of the right.

“District 9” is about slimy, crustacean-like aliens who ally themselves with a petty bureaucrat to protect themselves from the military. They scavenge, disregard property rights, spray gang graffiti. They’re soulful but gritty. They’re obviously metaphors for an oppressed minority. That’s why the film feels of the left.

These metaphors don’t reveal each film’s stupidity, just its politics. The stupidity comes, particularly for “District 9,” from adherence to the metaphor.

We quickly learn, for example, that 20 years ago an alien ship appeared over, not New York or D.C. or Paris or Beijing, but Johannesburg, South Africa. My thought: Cool! Plays off our movie assumptions. For three months nothing happened, the ship just hovered, and when we finally cut our way in we found the aliens malnourished and afraid. Interesting. They’ve traveled the galaxy but seem to have contracted a disease or something. So we transport the remainder of these aliens, over a million strong, into a neighborhood below, District 9, where they quickly become just another despised minority in just another slum on our planet. Um... Wait a minute.

We quickly learn, for example, that 20 years ago an alien ship appeared over, not New York or D.C. or Paris or Beijing, but Johannesburg, South Africa. My thought: Cool! Plays off our movie assumptions. For three months nothing happened, the ship just hovered, and when we finally cut our way in we found the aliens malnourished and afraid. Interesting. They’ve traveled the galaxy but seem to have contracted a disease or something. So we transport the remainder of these aliens, over a million strong, into a neighborhood below, District 9, where they quickly become just another despised minority in just another slum on our planet. Um... Wait a minute.

Here’s where the metaphor overtakes logic. Writer-director Neill Blomkamp wants the aliens to be a despised minority so that’s what they become. And that’s all they become. Despite the fact that they’re aliens and—I can’t stress this enough—the existence of aliens changes everything. It’s a Copernicus moment.