Movie Reviews - 2009 posts

Saturday January 02, 2010

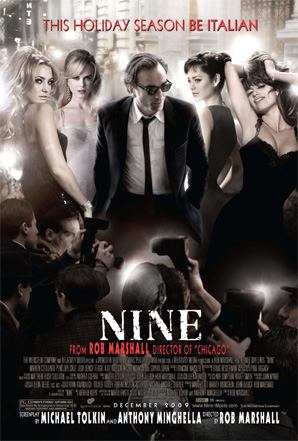

Review: “Nine” (2009)

WARNING: SPOILERS HERE...HERE...AND...(MMM)...HERE

I’m no marketer, so who am I to tell the Weinstein Co. how they should—or should've—marketed “Nine,” the Rob Marshall musical based upon the Broadway musical based upon Federico Fellini’s 1963 classic “8 1/2.” But given the film’s weak opening box office, here’s a thought. Instead of the tagline, “This Holiday Season: Be Italian,” why not plaster the poster with one of those sexy shots of Penelope Cruz and use these lines of hers from the movie?:

I’ll be here.

Waiting for you.

With my legs open.

When I sat down in the theater I knew I’d be seeing a lot of sexy women wearing sexy things and saying sexy lines but that was the  jaw-dropper for me. I think I coughed in surprise when she said it. I may have whimpered. Her lines, her presence, complicate the life of film director Guido Contini (Daniel Day-Lewis), but my thought, and probably the thought of every guy in the audience: I should have such problems.

jaw-dropper for me. I think I coughed in surprise when she said it. I may have whimpered. Her lines, her presence, complicate the life of film director Guido Contini (Daniel Day-Lewis), but my thought, and probably the thought of every guy in the audience: I should have such problems.

“Nine” looks great but suffers from two problems: 1) Most of the songs are so-so, and 2) the drama is internal and circular. It’s tough enough for movies to dramatize the creative process. How do you dramatize the non-creative process?

Guido Contini is a director whose earlier films redefined Italy for much of the moviegoing world in the early 1960s but whose latest films flopped. Now it’s 1965 and he’s a week away from starting film no. 9, titled “Italia,” but he has no idea what the story will be. He fakes his way through a press conference, he fakes his way through talks with his producer, he ignores calls from his muse and star, Claudia (Nicole Kidman). His costume designer, Lilli (Judi Dench), tells him, as he lays prostrate on her desk, that directing isn’t that tough. “You just have to say yes or no, what else do you do? ‘Maestro, should this be red?’ ‘Yes.’ ‘Green?’ ‘No.’ ‘Yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘yes,’ ‘no.’” She tosses her hands in the air. “Directing.” Unfortunately Guido has no answers, no yes/ no. Eventually he flees Rome down the coast of Italy in his light blue Alfa Romeo. My thought, and probably the thought of everyone in the audience: I should flee in such style.

Guido flees into the arms of his mistress, Carla (Penelope Cruz). He thinks she’ll clear his head but she clutters it. Worse, the production company follows him down. Worse, his wife, Luisa (Marion Cotillard), follows him down. She sees Carla, sparks fly, Carla is banished, Carla tries to kill herself. What’s a man with so many women to do?

As responsibilities and women tug at him in all directions, Guido’s life, certainly his creative life, swirls uselessly away. Nothing gets the attention it needs. He’s not stable husband to Luisa nor steady paramour to Carla; he has no work for Lilli or Claudia. Each woman has her own musical number but most of these are hardly show-stoppers and most don’t move the story further along but simply reiterate what we already know. The one show-stopper, the song you hum coming out of the theater and wish you could sing with the full-throated passion the singer does, is “Be Italian,” sung by Saraghina (Fergie), the whore from Guido’s youth who would show the neighborhood boys this and that for coins. She’s his first lust, the woman who started him on this journey of loving women too much and not enough, and she tells him, she sings to him:

Be Italian, be Italian

Take a chance and try to steal a fiery kiss!

Be Italian, be Italian

When you hold me don’t just hold me

But hold this! (clutches her breasts)

He’s stopped listening to this advice. He takes no chances and steals no kisses. Acclaimed and idolized, he’s the pursued now rather than the pursuer. Even a reporter from Vogue magazine, Stephanie (Kate Hudson), tries to get him into bed. Is the film suggesting a correlation between women and creativity? That when it becomes unnecessary to pursue the former, one is unable to pursue the latter? Fame has made Guido weak in the art of the pursuit.

Fergie, the one true singer in the bunch, belts it out, while the two main women in Guido’s life lock horns memorably. Cruz is pants-wettingly sexy while Cotillard is pained and effective. Her second number, “Take it All,” is staged as a burlesque, a sad striptease in which she gives up everything (the clothes are a metaphor) for this man who gives nothing back. Meanwhile, Dench, in her musical number, “Folies Bergeres,” flashes cleavage and seems completely French (in conversation she’s completely British). She seems to be having a great old time with the role.

The others? Hudson works fine, but the role is meaningless. Sophia Loren, playing Guido’s mother, has nothing to do. Kidman is an afterthought.

And Day-Lewis? It’s critically sacrilegious to write this but he may be wrong for the role. It’s not much fun watching him run circles in his head without having the decency to turn something into butter. Or, as Brando suggested, to get it.

The movie’s definitely missing oomph. Like Guido, it ignores the wisdom of Saraghina. Its British star is surrounded by actresses from France, Spain, Australia and America, leaving no one important to be Italian.

Wednesday December 30, 2009

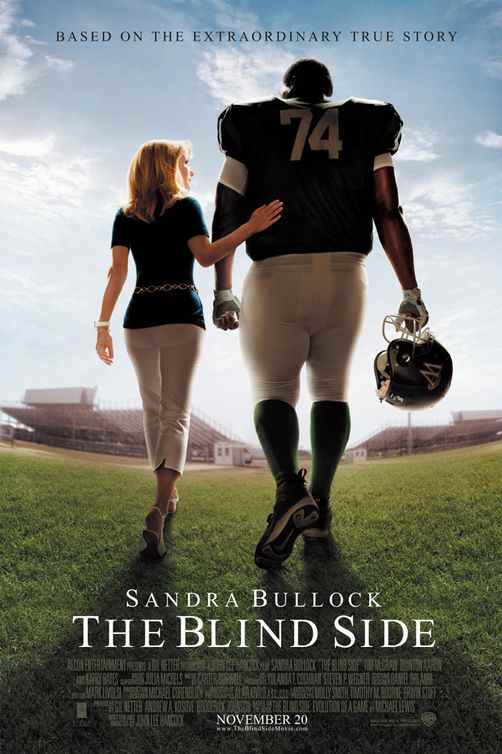

Review: “The Blind Side” (2009)

WARNING: BLITZING, 350-POUND SPOILERS

Nothing about “The Blind Side” pleased me more than its opening shot: grainy footage from a 1985 “Monday Night Football” game in which Lawrence Taylor sacked Joe Theismann, fractured his leg and ended his 11-year career. I was pleased because that’s how Michael Lewis’ book begins. “From the snap of the ball to the snap of the first bone is closer to four seconds than to five,” Lewis writes in his opening sentence; and in those five-closer-to-four seconds Lewis sets the scene, pulls back, writes about fear as a factor in the NFL, writes about the fear that Lawrence Taylor created and the fearlessness with which Joe Theismann played, and then circles back to the incident:

Theismann has played in 163 straight games, a record for the Washington Redskins. He’s led his team to two Super Bowls, and won one. He’s thirty-six years old. He’s certain he still has a few good years left in him. He’s wrong. He has less than half a second.

It’s the most famous injury in football history because the reverse-angle instant replay shows the bottom half of Theismann’s leg, between his knee and ankle, bending and snapping beneath Taylor’s weight, exposing the bone. The player who blocks the Lawrence Taylors of the world, by the way, is the offensive left tackle. He’s the guy who protects the quarterback’s blind side. And since free agency came to the NFL in the early 1990s, the second-highest-paid position in the NFL, after quarterback, is not running back nor wide receiver nor even middle linebacker (Lawrence Taylor’s position), but offensive left tackle. You pay most for the most-important position. You pay second-most for insurance for the most-important position.

Great offensive left tackles are highly paid because they require a set of physical characteristics that almost contradict each other. These guys have to be bigger than big and quicker than quick, and, let’s face it, the bigger-than-big usually aren’t quicker-than-quick.

Great offensive left tackles are highly paid because they require a set of physical characteristics that almost contradict each other. These guys have to be bigger than big and quicker than quick, and, let’s face it, the bigger-than-big usually aren’t quicker-than-quick.

And all of this leads to the story of Michael Oher—the story we came to see.

So I was pleased seeing the “Monday Night Football” footage, and hearing Sandra Bullock’s faux southern accent reading Lewis’ lines. But then writer-director John Lee Hancock, or Alcon Entertainment, or Warner Bros. Pictures, decided not to show the reverse-angle instant replay. They shied away from that harsh reality. It was a sign of things to come.

Michael Oher, one of 13 children born to a crack-addicted mother, grew up on the west side of Memphis in the projects known as Hurt Village. He drifted from apartment to apartment, school to school, barely getting by, when, at 14 or 15, a friend’s father, Big Tony, made an appeal to a rich, white, Christian private school, Briarcrest, to take both his boy, and his boy’s friend, Big Mike. Big Mike didn’t exactly fit in at Briarcrest—and not just because of his size or the color of his skin. He had a 0.6 GPA, he spoke to no one, he wore the same clothes day after day. Soon, though, he was being helped along, in particular by the Tuohy family, and in particularly by Leigh Anne Tuohy (Sandra Bullock). Eventually he came to live with them. Eventually they adopted him. And eventually he became a football star, one of those bigger-than-big, quicker-than-quick athletes who make great offensive left tackles. He starred at Briarcrest, then at Ole Miss, the Tuohys’ alma mater, and just this year he was drafted by the Baltimore Ravens with the 23rd pick of the first round. He’s now a millionaire.

It’s a feel-good story. So why is Michael Lewis’ book so good and John Lee Hancock’s movie so feely?

Sometimes it’s small differences. Here’s Lewis on a crucial moment in the story:

That day Leigh Anne went out and bought a futon and a dresser. The day the futon arrived, she showed it to Michael and said, “That’s your bed.” And he said, “That’s my bed?” And she said, “That’s your bed.” And he just stared at it a bit and said, “This is the first time I ever had my own bed.”

That’s nice. Poignant without being pitiful. Here’s Hancock’s version:

Michael (running his hand over the futon): This is mine?

Leigh Anne: Yes, sir.

Michael: I never had one before.

Leigh Anne: What—a room to yourself?

Michael: A bed.

The way that Aaron portrays Oher doesn’t help. Reading Lewis’ book, I imagined Michael as a blank, possibly a stoic, not outwardly pathetic, but that’s the way Aaron portrays him. There’s a “woe is me” quality. His eyes are sad, constantly sad, staring-at-the-ground sad. It’s Sad 101.

Basically Hancock takes what is already a sentimental story and sentimentalizes it. In the book it takes the Tuohys months to give Michael a home; in the movie it takes a day. In the movie, Michael is scary to the kids on the playground because he doesn’t smile when he talks to them; in the book, in reality, the kids were actually fascinated with this gentle giant, but were scared because, when they spoke to him, he didn’t talk back; he just stared.

Hancock personifies the dangers of Hurt Village in one gangster and the prejudices of the white community in the ladies-who-lunch, when both the dangers and the prejudices are more diffuse. I understand why Hancock does it. I also understand why it rings hollow—particularly when Leigh Anne shuts this gangster up by mentioning her gun and membership in the NRA.

Bullock’s the star, so much of the story has to be invested in her character at the expense of other characters. As a result, one of my favorite scenes in the book is gone. It’s the scene where the high school football coach’s assistant, Tim Long, who was an offensive lineman in the NFL, finally tells Coach Freeze that, with Michael playing, they don’t need all the fancy plays Freeze likes running. They can win with just one play: “We can run Gap,” he says. Meaning the quarterback hands off to the running back, who runs behind Michael Oher, who clears the field. Two weeks later Freeze adopts it. Lewis writes:

Seven plays into the game the score was 14-0 and they had done nothing but give the ball to their stumpy five three running back...and told him to follow Michael Oher’s right butt cheek. ... By the end of the first half, Briarcrest had scored 40 points.

Wouldn’t that have made a great scene? Instead Leigh Anne tells Michael, who’s not doing so well in practice, to protect the quarterback like he’s family, like he’s her. Then she chastises the coach, the fictional Coach Cotton (Ray McKinnon), for not knowing his players better. “Michael scored in the 98th percentile in protective instincts,” she says. Protective instincts? They test on that?

When the movie was first released, right-wing cultural bloggers—surely the whiniest people on the planet—complained about a quick George W. Bush gag and recommended like-minded folks stay away. They haven’t, of course. “The Blind Side” had a production budget of $29 million, expected to make two or three times that, and will soon make over $200 million domestically. It shows no signs of stopping. It’s got legs like Sandra Bullock.

What’s not to like for these folks? It’s a story about a southern Christian family who demonstrate real Christian values, and whose gestures of good will come back to them two-fold. The Tuohy family changes Michael’s life; he changes theirs. If anything, Hancock mutes the Democratic angle. The “Charge of the Light Brigade” scene is a good scene in the movie, but, again, it reads truer in the book. Sean Tuohy (Tim McGraw), taking over momentarily from Michael’s tutor, Miss Sue (Kathy Bates), who’s a Democrat, teaches Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem to Michael:

Their’s not to make reply

Their’s not to reason why

Their’s but to do and die

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred

Sean and Michael talk about what this means. They talk about loyalty and courage. And in the book, from the next room, Miss Sue suddenly shouts out, “Michael Oher, if there’s a war broke out, you head straight to Canada! You hear me?” Now don’t tell me Kathy Bates wouldn’t have nailed that line. Instead: nothing. Maybe because it didn’t fit in with the scene as they imagined it. Maybe because they didn’t want to upset folks. Maybe because. But there’s tons of stuff like that. What gives texture to the book is removed from the movie.

I hope a few of the people who love this movie seek out and read the book. I know it’s not revolutionary to say but the book’s better—for the reasons listed above. Maybe for this reason most of all: John Lee Hancock, backed by millions of dollars, major actors and a major studio, isn’t as good a storyteller as Michael Lewis is, backed by a keyboard.

Saturday December 26, 2009

Review: “Me and Orson Welles” (2009)

WARNING: FRIENDS, ROMANS, COUNTRYMEN, LEND ME YOUR SPOILERS!

Richard Linklater’s “Me and Orson Welles” has one of the best supporting performances of the year wrapped in a fun if slightly tinny story with a weak lead.

I don’t say this out of spite. I root for Zac Efron. He’s near the center of our culture (at the moment) and I root for our culture. I want it be worth it. Nearly 50 years ago a bunch of girls put the Beatles at the center of our culture and that turned out pretty well.

So I was rooting for Efron to be better than I thought he was. He plays Richard Samuels, a high school student in 1937 who is enamored of acting, the theater, singing and art. He wants to create. We see him for a moment at school, studying the 16th century, before the movie lets him loose in Manhattan, and he quickly meets an aspiring writer, Gretta Adler (Zoe Kazan, granddaughter of Elia). She’s even more enamored of art than he is—she has that solipsistic quality peculiar to artists: forever lost in her own mind—and she’s trying to get a short story into the already hallowed pages of The New Yorker. Outside, she talks of a writing teacher who would critique her work by waggling his hand back and forth and saying, “Possibilities,” and, just before the two part, she, forever thinking like a writer, says, “Wouldn’t this be a great scene for a story? Two people meeting like this and no more?” Richard waggles his hand back and forth. “Possibilities,” he says.

So I was rooting for Efron to be better than I thought he was. He plays Richard Samuels, a high school student in 1937 who is enamored of acting, the theater, singing and art. He wants to create. We see him for a moment at school, studying the 16th century, before the movie lets him loose in Manhattan, and he quickly meets an aspiring writer, Gretta Adler (Zoe Kazan, granddaughter of Elia). She’s even more enamored of art than he is—she has that solipsistic quality peculiar to artists: forever lost in her own mind—and she’s trying to get a short story into the already hallowed pages of The New Yorker. Outside, she talks of a writing teacher who would critique her work by waggling his hand back and forth and saying, “Possibilities,” and, just before the two part, she, forever thinking like a writer, says, “Wouldn’t this be a great scene for a story? Two people meeting like this and no more?” Richard waggles his hand back and forth. “Possibilities,” he says.

It’s a nice scene, but it lays open the Efron problem. Richard doesn’t have that artistic/solipsistic quality. Gretta is deeply into what she wants. What is he after?

Later that afternoon Richard comes across a group of actors spilling out into the streets, joking, preening, and one of them, Norman Lloyd (Leo Bill), attempting a drumroll. Richard offers his drum expertise and pulls it off, even as the director of these actors, 21-year-old Orson Welles (Christian McKay), emerges from the building. Spotting the new blood, he asks him to sing, then asks him if he can play the ukulele, then hires him on the spot to play Lucius in their production, the Mercury Theater’s production, of Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar.” In the quiet after Orson leaves by ambulance (as is his wont, because it gets him where he wants to go faster), Richard asks what became of the previous Lucius:

“He had a personality problem with Orson.”

“Meaning?”

“Meaning he had a personality.”

The film wants Richard to be an observer to the unfolding events—the chaotic manner in which a theatrical masterpiece is created—but he doesn’t have the nothing quality of a mere observer. Inside the theater, with his position small and tentative, he moves like someone who’s used to being center-stage. He follows Orson but not sycophantically. He spends time with Sonja Jones (Claire Danes), who works in the office while calculating to meet David O. Selznik, and he flirts with her, sure, but he doesn’t seem to set his sites on her until the other actors in the troupe, adults all, act jealous that he has entré with the woman they’ve dubbed “The Ice Queen.” He takes things for granted but not in the way the young take things for granted. It feels off.

There are some nice moments. We worry how he’ll do with this role he’s lucked into, and during first rehearsals he says his line (“Here is the man who would speak with you”), exits incorrectly, then correctly, then breathlessly asks a guy backstage how he did. “I cried,” the guy dryly responds without looking up from his magazine.

But the nice moments don’t add up to a whole. His family worries about the hours he’s keeping but nothing comes of it. He falls asleep at school but nothing comes of it. He takes Sonja out to dinner, runs into Gretta again, follows Orson to a radio broadcast. Eventually he sleeps with Sonja at Orson’s place. At first he seems nonchalant, then nervous, then petrified. He’s obviously never slept with a girl before, and Efron pulls it off, but this knowledge clatters among everything else we know, and don’t know, about Richard. His parts don’t add up to a whole, either. “Tell me who you are,” Sonja asks at one point. Yes, please.

We also don’t get a sense of what a breakthrough this “Caesar” is for the Mercury Theater and Orson Welles. Does anyone even mention that it’s set in Mussolini’s Italy? That the death of Cinna the Poet comes at the hands of the Secret Police rather than a mob?

The night before “Caesar” opens, with the show still in chaos, Orson beds Sonja, Richard reacts badly (like a cuckold), and Orson fires him: “I hope you enjoyed your Broadway career, Junior, cause it’s over.” Richard is stunned to find out he doesn’t matter, then stunned to find out he does. Welles has to woo him back for this small part. It works. Opening night’s a big hit. But in the excitement afterwards, Richard feels himself cut off from the rest of the cast. It’s up to Joseph Cotten (a perfectly cast James Tupper) to relay the bad news that he’s been fired after all. “It’s Orson,” Cotten says. “He can’t be wrong.”

McKay, by the way, should get a best supporting actor nomination. He not only offhandedly sounds like Welles, he displays the energy and fierce intelligence that Welles displayed onscreen. When his eyes light up with an amused, thick-as-thieves look, I thought: Harry Lime lives. Then there's opening night. Welles is backstage listening to the waves of applause, and says, to no one in particular, “How the hell do I top this?” A second later you see his mind begin to work on that question. We already know the answer but you get the feeling he doesn’t—yet. That’s how good McKay is.

“Me and Orson Welles” is, as I’ve said, a fun movie, but at times it has an artificial, tinny quality that I associate with latter-day Woody Allen. It’s if the characters are less characters than puppets to be moved around the stage to make the point the author wants to make. Events feel externally rather than internally driven.

Yet it’s not without its poignancy. At the end, Richard runs into Gretta again, and she thanks him—not enough—for helping get her story published in The New Yorker. The two, flush with their momentary successes, talk creativity and art. “It feels like it’s all ahead of us,” she says, and it was, then, 70 years ago. But we know their successes, if they have successes, will be small and short-lived, even as we know Welles’ successes, while gigantic, will lead to Paul Masson commercials in the '70s and “Transformers” voiceovers in the '80s. In Gretta's earlier story, the word “possibilities” is, both to her and her writing teacher, pejorative. By the end, seeing these people in a moment before everything plays out, one feels the sadness of choices made; and one appreciates the beauty of possibilities.

Wednesday December 23, 2009

Review: “Avatar” (2009)

WARNING: EYE-OPENING SPOILERS

James Cameron’s “Avatar” is the purest adventure story I’ve seen at the movies in a long time.

It’s also the most subversive blockbuster released during this long, ugly decade. Hell, it’s not even subversive. It states its apostasy out loud. “We will show the sky people they cannot take whatever they want!,” Jake, the avatar, shouts before the final battle. “This is our land!”

Psst: We’re the sky people.

The movie begins as a tale of twins. Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) is a U.S. Marine who loses his legs in an unnamed war, and he has a twin brother, Tommy, a Ph.D. scientist scheduled to work on a moon light years away named Pandora. The human scientists on Pandora use avatars, which match the scientist’s DNA with alien DNA, to study the native Na’vi people, who are nine feet tall and blue-skinned. Then Tommy dies, rendering his avatar useless. Unless of course someone can match his DNA. Hey!

![]() When Jake arrives on Pandora, there’s a balance of power among the human population there, and each has its own agenda. The scientific community, led by Dr. Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver), wants to learn about the Na’vi; the business community, led by Parker Selfridge (Giovanni Ribisi), wants to exploit the unobtainium under Na’vi land; and the military community, led by Col. Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang), wants to kick some ass. But they all need each other. Science needs the funding business provides. Business needs the knowledge, and the diplomacy, science provides. And if it weren’t for business and scientific interests, the military would have no opponent—at least on Pandora.

When Jake arrives on Pandora, there’s a balance of power among the human population there, and each has its own agenda. The scientific community, led by Dr. Grace Augustine (Sigourney Weaver), wants to learn about the Na’vi; the business community, led by Parker Selfridge (Giovanni Ribisi), wants to exploit the unobtainium under Na’vi land; and the military community, led by Col. Miles Quaritch (Stephen Lang), wants to kick some ass. But they all need each other. Science needs the funding business provides. Business needs the knowledge, and the diplomacy, science provides. And if it weren’t for business and scientific interests, the military would have no opponent—at least on Pandora.

Jake’s a man without a community. The scientists don’t want him because he’s a jarhead, and the jarheads dismiss him as “Meals on Wheels.” But Col. Quaritch sees a use. “A Marine in an avatar body,” he says. “That’s a potent mix.” He asks for reports. If Jake does his duty (again), he’ll get him his legs back. Meaning the technology was always there, they just didn’t think him worth the expense. Nice.

“One life ends, another begins,” Jake says of his brother and himself, but he could be talking about himself and his avatar. He has a new twin now, and, during the course of the movie, his avatar is taken through the hero cycle. He’s wobbly the moment he wakes up, but soon he’s luxuriating in the thrill of what Jake’s real body can no longer do. Standing. Walking. Running. Digging into the dirt with his toes.

In the jungle, after a thrilling stand-off with a hammerhead titanothere (think: elephant/rhino), and an even more thrilling chase through the woods by a thanator (think: huge, armor-plated tiger), Jake, separated from the scientist/avatars, is saved from a pack of prowling viperwolves (think: super-panthers) by a Na’vi, Neytiri (Zoe Saldana), who, afterwards, contemptuously dismisses his gratitude. “You don’t thank for this,” she tells him before the body of a dead viperwolf. “This is sad. Very sad only.” She blames him for the death of the viperwolves. “You’re like a baby, making noise, don’t know what to do.” When he asks why, then, he bothered to save her, she responds, “You have strong heart. No fear. But stupid.” It’s a good back-and-forth. Those who remember only Cameron’s “Titanic” dialogue may be surprised.

She’s lying, by the way. The reason she saved him, the reason she didn’t kill him herself when she had the chance, was because the seeds of a holy tree, looking like aerial, benign jellyfish, floated in front of her arrow. A sign from Eywa, her God. And as they argue in the jungle, more of these seeds float by, alight on Jake, and amaze her. Which is when she decides to take him to back to her tribe, where she is a princess, the daughter of tribal leader Eytukan (Wes Studi) and spiritual leader Moat (C.C.H. Pounder), and betrothed to Tsu’tey (Laz Alonso). They know Jake’s a dreamwalker, an avatar of the “sky people,” but they let him live because he’s a warrior (and thus one of them), and because they hope to learn about the sky people through him. They also appoint Neytiri to teach him about their ways.

Reluctant at first, calling him a moron throughout, Neytiri teaches him how to ride a pa’li, or direhorse; how to climb; how to fall from great heights using giant leaves to break the fall. All the while Jake is reporting back to the Colonel. Eventually Grace gets wind of this and moves the entire operation to the floating mountains of Pandora, where, in the flux vortex, they’re harder to contact, and where their research can continue uninterrupted. They have only three months until the bulldozers arrive to tear down Hometree.

“Avatar” is 160 minutes long yet there’s little fat in it. Cameron expertly guides us through long set pieces (Jake’s first day and night in the jungle), to shorter montage scenes (Jake’s Na’vi training), and back again. Bit by bit, Jake’s avatar fills out and grows stronger. He learns the rudiments of the language and the religion, which involves the flow of energy and the spirit of animals, and which he calls “tree hugger crap” even as he’s swept up in it. The Na’vi literally bond with animal and plant life through live tendrils in their braids. One of the last tests before he can become a man, and thus take another step in the hero cycle, is to bond for life with an ikran, or banshee, all of which nest in the floating mountains. And how will his ikran choose him? “It will try to kill you,” Neytiri answers matter-of-factly. “Outstanding,” Jake, the jarhead, answers.

Jake and Neytiri both have this spirit of adventure—as does the film. And when Jake finally gets his ikran, he and Neytiri soar through the air together—menaced only by two things: the huge red toruk, the baddest thing in the Pandora skies; and time. Their three months are almost up.

“Everything is backwards now,” says the human Jake, his jarhead cut grown out, scratching his beard. “Out there is the real world and in here is the dream.” So it is with us in the audience. Jake’s avatar initially seems bizarre, but, over time, it’s the avatar, the Na’vi Jake, that appears normal, while his human self seems small and undefined. So it is with the 3-D technology. Initially it seems obtrusive. After a while you don’t even notice it. Earlier this year, Cameron told a French journalist. “It's not just about literally seeing [the Na'vi] but about perceiving differently —perceiving through the eyes of the other person. That's what cinema's all about to me.” And that’s what it is here.

When the “Avatar” trailer hit the Web in August, an almost universal cry of pain went up among the geekish: That’s it? they asked. They felt its plot was too reminiscent of “Dances with Wolves”—military man sent to watch indigenous people and sides with the indigenous against his own—but of course “Dances” was a good movie, and this is an old plot anyway. Think “Lawrence of Arabia,” “Pocahontas” or “The New World.” Think especially Edgar Rice Burroughs’ “John Carter of Mars,” since that’s the story that influenced Cameron the most. Published near the turn of the last century, Carter, a Virginian and a Captain in the U.S. Civil War, dies, or “dies,” in a cave in Arizona and wakes up re-embodied on Mars, where he becomes a warrior-savior among its humanoid inhabitants. During the course of the stories, he keeps traveling back and forth between Earth and Mars, between his two selves. Like Jake.

What Carter doesn’t share with Jake is a sense of guilt; a sense of almost constant betrayal. When the bulldozers arrive, Jake’s the first to stop them, betraying the humans. But the intel he provided allows the military to destroy the Na’vi’s home, the gigantic Hometree, which comes crashing down like one of the twin towers. Neither side can forgive his treachery. The Na’vi tie up the avatar Jake while Selfridge pulls the plug on the avatar project and the Colonel’s men toss the scientists, and the human Jake, into the brig. What balance of power existed is gone. It’s a military-industrial complex now.

But an iconoclastic chopper pilot (Michelle Rodriguez) springs the scientists, and flies them, and a makeshift lab, to the Tree of Souls, the Na’vi’s most sacred place. Jake is returned to his avatar body, which has been left behind after the destruction of Hometree, and he walks among its ashes. It’s a poignant scene—particularly if one recalls his earlier joy at kneading the dirt with his toes. To win back the trust of the Na’vi he knows he must do something spectacular and foolish, and it involves the toruk, the baddest thing in the skies, which Neytiri told him has only been tamed (ridden) five times in Na’vi history. But Jake figures if you’re the baddest thing in the skies you have no natural predators, and thus no need to look up. Which is why, on his ikran, he divebombs the toruk. I love the logic of this. I love how Cameron films it, too. Just as Jake leaps, we cut to the Na’vi chanting to Eywa at the Tree of Souls. Then a shadow appears. They cry and scatter in terror (it’s a toruk!)... and then in wonder (it’s a toruk... ridden by Jake!). Cue incendiary battle speech. Cue final battle scenes.

Of course the Na’vi, with bows and arrows, have little chance. They gain an advantage with a surprise attack but lose it because of the humans’ superior firepower. How do they gain it back again? Through a deus ex machina. A literal deus ex machina. They have God on their side.

Most adventure movies inevitably end with a final confrontation between hero and villain, and Cameron’s are no different, but his tend to involve like battling like. In “Aliens,” it was two matriarchs. In “Terminator 2,” it was two terminators. Here it’s two avatars. Jake, as a Na’vi, takes on Col. Quaritch, outfitted in the same kind of mechanized, supersized warrior suit Ripley wore at the end of “Aliens.” Neither avatar does the killing, though. Neytiri does. And this time it’s not sad only.

James Cameron has done an amazing, ballsy thing with ”Avatar." Yes, he imagines an entire world and creates it in meticulous detail. Yes, he sends his main character on a hero’s journey through this world. But within this framework, this age-old story, he critiques the worst aspects of our own culture. “When people are sitting on something you want, you make them your enemy,” Jake says near the end, summing up the sad history of the human race. It’s not an abstract or ancient history, either. It’s current. The villains in “Avatar” use the language of this decade: “Shock and awe”; “fighting terror with terror”; “balance sheets.” They are us. “Dances with Wolves” was set in an historical timeframe, more than 100 years earlier, in which everyone knew the Native Americans would fight and lose. Not here. Here, in this future setting, the humans not only lose but they’re sent back to Earth—to their dying planet that has no green on it. They lose because God literally isn’t on their side.

Wow.

That James Cameron could get such a message into a fantasy epic, a Hollywood blockbuster, is truly more astonishing than any of the astonishing computer graphics within it.

Wednesday December 16, 2009

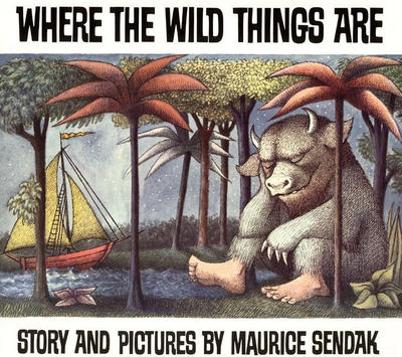

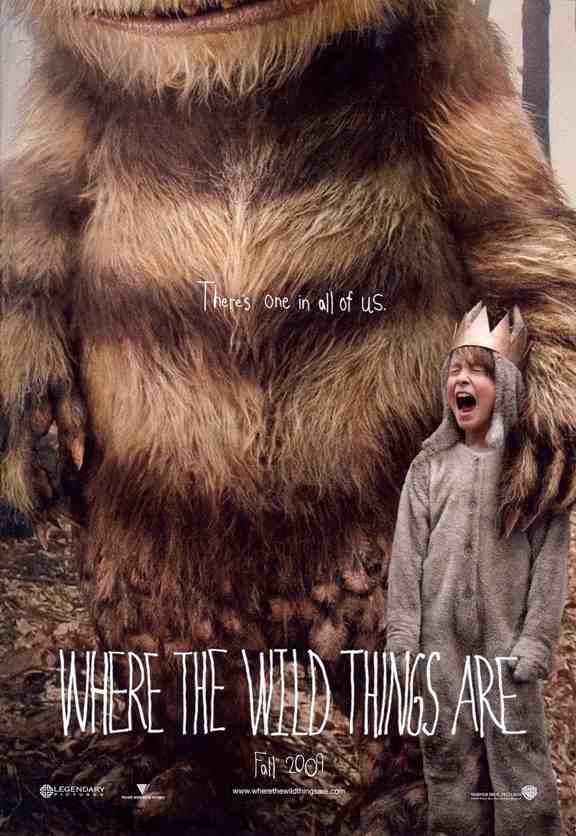

Review: “Where the Wild Things Are” (2009)

WARNING: WILD-RUMPUS SPOILERS

Both Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are” and I were born in 1963, and by the time I was Max’s age it was hugely popular but I wasn’t a fan. I guess I didn’t have much of a wild thing in me. I was a sickly kid, and fairly obedient, so not the type to tackle the family dog or start a snowball fight with bigger kids—both of which Max (Max Records) does in the first 10 minutes of Spike Jonze’s adaptation and expansion of Sendak’s work. It’s a brilliant first 10 minutes. Before we see anything we hear Max, humming, and before we see Max we see his handiwork: all of the movie-studio logos,  from Warner Bros. to Legendary Pictures, have been defaced, the last one reading M-A-X. Then we get Max himself, in wolf costume, chasing and tackling the family dog, at which point Jonze freeze-frames and gives us the title in childish script. At which point I went: “This is going to be good.”

from Warner Bros. to Legendary Pictures, have been defaced, the last one reading M-A-X. Then we get Max himself, in wolf costume, chasing and tackling the family dog, at which point Jonze freeze-frames and gives us the title in childish script. At which point I went: “This is going to be good.”

The photography is so muted, the colors so washed out, that the movie not only feels like it takes place in the 1970s but was filmed in the 1970s. Max is a rambunctious kid, possibly friendless, living with a teenaged sister and a divorced mom (Catherine Keener). When friends come to pick up his sister, he attacks them with snowballs and then gleefully runs back to his newly made snow fort. But they’re wild things, too, and bigger, and they follow and collapse the fort, leaving Max tearful—probably less physically hurt than emotionally hurt. His sister watched the destruction and did nothing. In revenge, he runs into her room, stomps the snow off his body, rips up gifts he’s made for her. Anger spent, regret sets in. This cycle of creation-destruction-regret continues throughout the movie.

We see him briefly at school. His science teacher is offhandedly explaining that the sun is a fuel source, and, like all fuel sources, will eventually expend itself and everything in our solar system will die. Attempting to cover up this awful fact, he digs deeper: He talks up the ways mankind will destroy itself before then. More creation-destruction-regret cycles. More callbacks to the 1970s. Back then, in the midst of my own parents’ divorce, it seemed I was surrounded by destruction scenarios, and one in particular stuck with me: an “In the News” report (sponsored by Kellogg’s) shown between Saturday-morning cartoons, in which it was reported that a graduate student wrote his doctoral dissertation on how to build an atom bomb. The meta-message: If one individual can do it, what country, with many individuals at its disposal, can’t? The knowledge was out there and couldn’t be bottled up. It made you feel small and powerless. It made you cling to fantasies of being all-powerful.

Max clings to such fantasies. His sister’s on the phone and his mother’s entertaining a man who’s not his father. Everything’s moving away from him, he has no say, and he’s bored. So he rebels. He acts bratty with his mom, then fights with her, then bites her—the act, not only of a wild thing, but of the powerless. Then he runs away. He finds a boat in a creek, gets in, and sails away to the island where the Wild Things are.

In his journey, Jonze emphasizes the smallness of Max against the vastness of the ocean, the deserted beach, the steep cliff face, and, finally, the Wild Things themselves, who crowd around and talk of eating him until his cry of “BE STILL!” stuns them into silence. Then he declares himself their king. In essence, this restores things to the way Max perceived them early in life. He’s small and powerless, surrounded by big, powerful beings, with big heads and big mouths, but he rules.

On the island, events unfold that, one imagines, mirror events in Max’s real world. Carol (James Gandolfini). a defacto leader of the Wild Things, and both father and buddy to Max, is estranged from KW (Lauren Ambrose), who’s off with Bob and Terry. “What about loneliness?” Carol asks Max during his coronation. “Will you keep out the sadness?” So even in Max’s fantasy there’s an immediate sense that things are not whole. But in the midst of their “wild rumpus,” as they run, jump, howl at the moon, KW returns, and they all hogpile together and sleep together, rather than in the separate cocoons (literal and metaphoric) that Carol was smashing earlier. “We forgot how to have fun,” Carol says as they drift off to sleep. Max showed them.

On the island, events unfold that, one imagines, mirror events in Max’s real world. Carol (James Gandolfini). a defacto leader of the Wild Things, and both father and buddy to Max, is estranged from KW (Lauren Ambrose), who’s off with Bob and Terry. “What about loneliness?” Carol asks Max during his coronation. “Will you keep out the sadness?” So even in Max’s fantasy there’s an immediate sense that things are not whole. But in the midst of their “wild rumpus,” as they run, jump, howl at the moon, KW returns, and they all hogpile together and sleep together, rather than in the separate cocoons (literal and metaphoric) that Carol was smashing earlier. “We forgot how to have fun,” Carol says as they drift off to sleep. Max showed them.

The next day, in a journey across the desert, Carol shows Max his secret cave with his model city, and Max declares that they will build their own city, a real city, where only things that they want to happen will happen. This city, this home, winds up looking like the cocoons they were smashing earlier, but big enough for everyone. Shortly after, though, Max follows KW across the desert to meet Bob and Terry, two owls whose wisdom is incomprehensible, and she brings them back to the new perfect home, setting in motion its destruction. “Why did you bring them here?” Carol asks Max angrily. “This was supposed to be for us.” For a time, Max distracts everyone with a dirtball fight but it mirrors the earlier snowball fight, ending badly with hurt feelings. Everything is breaking up again. The Wild Things demand that Max use his powers to make everything right but his powers turn out to be a robot dance with which, earlier in the movie, he’d tried to cheer up his mother. “That’s what we waited for?” they ask in disbelief. Carol’s anger can barely be contained. “It wasn’t supposed to be like this,” he says. “You were supposed to keep us safe.” Others counsel acceptance: “He’s just a boy pretending to be a wolf pretending to be a king.”

In this way Max’s fantasy of absolute power and absolute safety turns into a fable of acceptance. Every Wild Thing has faults. Carol is fun but with a hair-trigger temper, KW is maternal but keeps bringing in agents of destruction, Judith (Catherine O’Hara) is carping and critical but often correct. Ira (Forest Whitaker) can make great holes but he’s passive. Alexander (Paul Dano) is a goat no one listens to. And Max is a boy, made king, made parent, and made to recognize the limits of parental power and authority. Things break up. Things change.

Is “Where the Wild Things Are” a movie for kids? I don’t know. My nephew, Ryan, 6, liked it, while my nephew, Jordan, 8, didn’t. But it’s definitely a movie for adults. It has the feel of a classic. Then there’s this high praise from a friend, a mother with two sons: “It helped me understand boys.”

Monday December 14, 2009

Review: “Invictus” (2009)

WARNING: SEPARATE-AND-UNEQUAL SPOILERS

Clint Eastwood’s “Invictus” begins with a rugby team—the national rugby team of South Africa, it turns out, the Springboks—practicing on lush green fields bordered by a sturdy, iron fence. Just across the street, black kids are playing on scabby, dusty fields bordered by a cheap chain-link fence. So it goes. Then a caravan approaches on the road between them, and, as it continues past, the black kids cheer while the white players stand in stony silence. It’s February 11, 1990, and Nelson Mandela (Morgan Freeman), unseen in the caravan, has just been released after 30 years in prison on Robben Island. The scene is basically a metaphor for the divided country: At that moment, Mandela is the only one traveling in the divide between the two separate and unequal societies.

Four years later Mandela is elected president of South Africa. On his first full day on the job, he takes a 4 a.m. walk with his security team then shaves. We see him staring at himself in the bathroom mirror, white foam covering half his face, doubt in his eyes. His face is basically a metaphor for the country: half-white, half-black, unsure of what lies ahead.

By the end, as two pairs of hands, one white and one black, hold aloft the World Cup trophy, I couldn’t help but think I was back in 1959 watching a Stanley Kramer movie.

By the end, as two pairs of hands, one white and one black, hold aloft the World Cup trophy, I couldn’t help but think I was back in 1959 watching a Stanley Kramer movie.

It’s a shame that Eastwood underscores this particular point so much because there’s a lot I liked about, and learned from, “Invictus.” I didn’t follow Mandela’s career after he was released from prison, and, as an American, I knew nothing about rugby. I got to learn something of both.

Mandela in his first days in office is reminiscent of Barack Obama in his first days in office. The outgoing power structure, who excluded, expect similar treatment from the incoming power structure, but Mandela keeps offering inclusion. His openness, his forgiveness, is, yes, immediately pragmatic—the Afrikaners, Mandela tells his aide, Brenda, still control the police, the army, the banks—but it’s hardly soft. “Forgiveness liberates the soul,” Mandela says at one point. “It removes fear. That’s why it’s such a powerful weapon.” Forgiveness as a weapon? I’m sure Dirty Harry would have a quip about that—“It hardly beats a Magnum .44”—but Clint hasn’t been Dirty Harry for a while. His revenge/forgiveness motifs have evolved.

Others in South Africa are not so willing to forgive. The Springboks have long been viewed as a symbol of Apartheid. Black fans root against them and black kids refuse to wear their jersey. As a result, the National Sports Council, now run by blacks, vote unanimously to change the teams’ name, colors and emblem. They are going to eradicate the bastards and stick it to the Afrikaners. Until Mandela shows up and reminds them that by acting in such a manner, “We prove we are what they feared we would be.” His argument wins the day—just barely—and afterwards, in the back of the limo, his aide argues with him over expending his political capital in this manner. “So this rugby is a political calculation?” she asks. “It is a human calculation,” he answers. That’s a nice line. One of many nice lines early in the film.

There is already a backlash against the initial raves for Morgan Freeman. Many movie fans are understandably wary that, in the wake of Jamie Foxx as Ray Charles, Philip Seymour Hoffman as Truman Capote, Forest Whitaker as Idi Amin and Sean Penn as Harvey Milk—i.e., in four of the last five years—yet another “real life” performance will win the Oscar for best actor. At the same time, Freeman is impeccable here. He is rail-thin and fragile, burdened by the affairs of state, and yet lit from within. He is, as ever, beautiful to watch, in a role that’s worthy of him.

But we begin to lose him halfway through as the focus shifts to the Springboks. He has team captain Francois Pienaar (Matt Damon) over for tea and talks to him about inspiration. The World Cup arrives in South Africa, and the Springboks, expected to fare poorly, particularly by a snide sports reporter (the nearest thing to a villain in the movie), begin to win, and, in that winning, begin to unite the country. These rugby scenes are fascinating to me because, except for a small training session the team gives to shantytown kids—in which it’s explained that the ball can’t be passed forward, only sideways or backward—the games happen without explanation. Yes, much of it is familiar. It’s another sport played on a rectangular field, with two goals, a ball, and a time limit. But the subtleties are lost, and Eastwood doesn’t help. For a time I didn’t even know if there was a clock, since Eastwood never cuts to it. The team simply, suddenly, raises its arms in victory. “We win!” Really? Oh, good. Then they play France in the rain and appear to be losing. No, they suddenly raise their arms in victory. “We win!” Really? Oh, good.

In this manner the Springboks reach the finals against a fierce New Zealand team.

Allow me to play the nattering aide in the back of the limo for a moment. “Invictus” might have worked better if Eastwood hadn’t spent his artistic capital on the irrelevant. After a great introduction of Mandela’s security detail, in which the white guards may have once incarcerated the black guards, these guys are mostly played for laughs. They deserve better. We get two red-herring attacks on Mandela (the van at the beginning, the airplane before the finals) and both could’ve been dealt with more subtly. We didn’t need to cut between the van and Mandela, for example; just show us the van squealing to a sudden stop in front of Mandela. That would’ve worked. Similarly, why get us into the cockpit of that airplane? That just confused.

Eastwood also goes for the estranged-daughter subplot again (see: “Absolute Power” and “Million Dollar Baby”) and spends too much superficial time with the Pienaars and their black maid. He spends too much superficial time on all manner of racial politics. During the finals, in shots worthy of Ron Howard’s “EdTV,” Eastwood gives us white people in white bars, and black people in black bars, all watching the same thing, all becoming united by the screen. He gives us a black scrounger edging closer to white cops listening to the game, being shooed away, edging closer again, and finally, in victory, being tossed in the air in celebration. Fans spill out into the streets, whites and blacks, celebrating together. White and black hands hold the trophy aloft. It’s all too much the same. It’s all too much.

Monday December 07, 2009

Review: “Up in the Air” (2009)

WARNING: UNCOMMITTED SPOILERS

Halfway through Jason Reitman’s “Up in the Air,” Ryan Bingham (George Clooney) explains the delicacy of firing people, and thus putting them between jobs, this way: “We are here to make limbo tolerable.”

Bingham is good at this because he enjoys limbo. He lives in limbo. The previous year he was on the road 322 days and in a voiceover he tells us that everything we hate about travel he loves: the recycled air, the bad sushi, and, mostly, the lack of connection. The other handful of days he spends in the home office in Omaha, Nebraska, where he stays in an apartment that has the blankness of a motel room. There’s nothing unique about it: no pictures, mementos, nothing that says Ryan Bingham except for the fact that there’s nothing that says Ryan Bingham. Bingham gives self-help seminars, too, across the country, entitled “What’s in your backpack?,” where he tells the audience to imagine everything they own in a backpack (photos, dishes, couches, cars), and to feel the weight of all that on their shoulders; then he encourages them to burn it all, starting with the photos. He tells them to do the same with their relationships, tossing in a joke about not necessarily burning them, but adding a warning that those relationships are the heaviest things they own. Life is better, he suggests, by traveling light and alone, as he does. He’s Nathan Zuckerman without the angsty Jewishness. He’s happy.

He’s also a prick.

He’s also a prick.

On the one hand I liked it: a Hollywood movie makes their main character a truly unlikable person. His job is to travel around the country and fire employees at companies where the bosses are too cowardly, or too uncaring, to do it themselves. And he’s good at his job. “Anyone who ever built an empire or changed the world sat where you are right now,” he says to the distraught, the broken, the angry. “And it's because they sat there that they were able to do it,” He tells people that this is their chance to follow their dreams. It’s a smart ploy. Most of us wound up working at places we didn’t imagine, doing things we don’t enjoy. The subtext of his message is basically: You and I both know I’m doing you a favor.

But at this point in the story Bingham seems too smarmy and self-assured to be good at his job. Even in the act of firing people, he still has that small George Clooney smirk on his face. One wonders why he hasn’t been busted in the nose yet.

Soon he and all the other corporate downsizers are called back to the home office at Integrated Strategic Management (ISM), where they’re introduced to Natalie Keener (Anna Kendrick), a business-school grad, who’s come up with two strategies to increase efficiency and profitability. The first strategy will take Bingham off the road; the second will downsize him.

ISM’s biggest expense is travel. So why not, in the Internet age, fire employees remotely? There’s a logic, and a kind of horror, to it. The act of firing someone is inhumane. Companies make it moreso by having a stranger do it. ISM makes it moreso by having a stranger do it remotely. One wonders where the inhumanity ends.

Not at her second strategy. For a century businesses have tried to figure out how to replace the skilled (and compensated) with the unskilled (and uncompensated). This strategy, in fact, may well define American business in the 20th century, and it’s a morally bankrupt, bottom-line, and, I would argue, dead-end strategy. And now it’s Natalie’s. Bingham has a skill. He knows what to say to keep the newly fired calm and get them out the door. So Natalie works on a flow chart, which can be given to the unskilled, who can then they say what Bingham would have said. At a fraction of the cost.

In this way employees would not only be fired remotely, and not just by a stranger, but by a stranger working robotically off of a flow chart. Its inhumanity makes Bingham seem humane. Which is why we begin to warm to him.

Fortunately Bingham demonstrates to Natalie, in front of their boss, Craig Gregory (Jason Bateman), that she knows nothing about firing people. Unfortunately Gregory sends the two on the road together so she can learn. Basically Bingham will teach Natalie what he knows, she’ll translate that knowledge to the flowchart, and Bingham will become expendable. Another reason we begin to warm to him.

The two meet bickering and continue bickering, with Bingham, the older and more articulate, always winning the day. Their greatest arguments are personal, not business. He successfully argues against marriage as another unnecessary connection, the heaviest thing in that backpack (“all the arguments and secrets and compromises”), and she seems distraught, comically distraught, that she can’t defend it. In a lesser film the two would get together but thankfully we hardly get a glimmer of that here. She’s got a boyfriend—we see them briefly kissing good-bye at the Omaha airport—while he’s got a fuckbuddy, Alex Goran (Vera Farmiga), a female version of himself whom he met in Dallas earlier in the film. There’s a great scene where they compare and contrast gold cards as foreplay. “We’re two people who get turned on by elite status,” she says.

In a Miami hotel lobby, Natalie finally breaks down, sobbing that her boyfriend broke up with her via text message (“That’s like firing somebody over the Internet,” Bingham deadpans), and collapses into Bingham’s arms—just as Alex arrives for another session. Instead the three gets drinks and talk over relationship expectations: Natalie’s (high) and Alex’s (low). They talk about settling or not settling. In Natalie’s description of her ex, one senses, not the love she argued for earlier, but a grocery list of positives she wants in her cart. Jason Reitman nicely refuses to underscore the point.

Then they crash a company party, where they drink, dance, go out on a boat, get stranded, arrive on the beach at dawn with their pantlegs rolled up and carrying their shoes. Bingham and Alex begin to seem like a couple. They begin to act tender with one another.

In his travels Bingham’s got his eye on a prize: 10 million miles, and super-elite status, on American Airlines. He’s also recently carting around a cardboard cutout of his sister and her fiancé, so that, like the gnome in “Amelie,” or like Flat Stanley, they can be photographed against various famous backdrops. It’s a cute thing for their wedding. Bingham photographs them, grumbling all the while (what a thing for his backpack!), but, as he warms to Alex, he warms to the charms of the task; and when the wedding approaches, he asks Alex along.

These two, used to super-elite status, acquiesce to the humble digs of this northern Wisconsin town. He reconnects with his sisters, shows Alex his old high school hangouts, and talks the fiancé, who gets cold feet, into commitment—a first. It changes him. So much so that in Vegas, giving his usual self-help seminar about the backpack, he smiles to himself, abruptly leaves the podium, and hops a flight to Chicago, where Alex lives. He’s ready, as the film’s poster says, to make a connection.

All the while I’m thinking: Really? This is it? This film, which I’ve heard so much about since the Toronto festival, and which is a clear front-runner for best picture, is going to take a guy who’s nasty and make him nice, empty and make him full, single and make him en couple?

Cue record-scratch. Because when Alex opens her door she’s surprised but not in a good way. Then we see kids running up the stairs behind her. Then we hear a voice calling out: “Honey? Who is it?” And Bingham’s face falls.

And I’m thinking: Niiiiice.

A second later I’m thinking: Wait. So why did Alex act the way she acted in Miami and Wisconsin? Like she was falling for him? It could be that I misread her, as Bingham misread her. She wasn’t concerned he wasn’t interested; she was concerned he was. I’d have to see the movie again to suss this out. At the same time it’s undoubtedly true that, since Miami, Bingham and Alex became less raunchy fuckbuddies than charming couple. Which is movement away from what Alex supposedly wanted Bingham for.

On the return flight he gets his 10 millionth mile; it feels hollow. Then an employee that Natalie fired, backing up a threat, kills herself, and Natalie quits and her program is dismantled. Bingham is on the road again. But is it what he wants? Can he acclimate others to limbo if he no longer enjoys it himself? One of the last shots is Bingham, at the airport again, staring up at the arrivals and departures board. It makes us think of all of our arrivals and departures in life—with jobs, friends, family; life and death. Staring up at the board, though, is something we’ve never seen Bingham do. He always knew where he was going before.

“Up in the Air” is a good, smart movie that’s getting the traction it’s getting because it’s timely. Unemployment, in the wake of the Global Financial Meltdown, is at 10 percent, and this is a movie about firing people. In fact, except for a few semi-famous faces (J.K. Simmons, Zach Galifianakis), the faces of the fired, explaining their feelings abut being fired, are the recently fired. “The filmmakers put out ads in St. Louis and Detroit posing as a documentary crew looking to document the effect of the recession,” IMDb tells us. “When people showed up, they were instructed to treat the camera like the person who fired them.” A good touch. A moral touch.

The movie also has smart, sharp dialogue. It’s a movie for adults. It treats business as it should: as an amoral, possibly immoral, enterprise. There’s always talk of company loyalty (to American Airlines, for example), when companies are loyal to no one. I laughed out loud when Natalie began her initial presentation to ISM employees: “If there’s one word I want to take with you today it’s this: GLOCAL.” Only at a company where everyone is worried about keeping their jobs would everyone not laugh at that. But I’ve heard worse in real life.

Should the movie have focused more on Natalie’s second strategy—replacing the skilled with the unskilled—or would such a focus have inevitably gotten too preachy? I suppose it’s enough that it’s dramatized. In the end, Bingham’s skills at downsizing aren’t downsized. His boss tells him, “I need you up in the air,” which is where the movie, appropriately, leaves him and us.

Wednesday December 02, 2009

Review: “Red Cliff” (2009)

WARNING: HEN DUO SPOILERS

John Woo’s “Red Cliff” is work. The movie is based upon the Battle of Red Cliffs, which took place in 208 A.D. and helped bring an end to the Han Dynasty. The period that followed, the Three Kingdoms, while short (approximately 70 years), has been romanticized in Asian culture via operas, novels, even TV shows and video games. As a result, most people in Asia know about this battle and its main characters. They don’t need them explained any more than we would need someone to tell us who Robin Hood and his Merry Men were.

But for us poor westerners? Friar who? Little what? It’s tough keeping everybody straight.

OK, so Cao Cao (Zhang Fengyi) is an imperial minister/general who intimidates even the Emperor of the Han dynasty into getting what he wants, which is full-fledged battle against rebel warlords Liu Bei (You Yong) and Sun Quan (Chang Chen), and a battle quickly ensues against Liu Bei’s army, which includes master strategist Kong Ming (Takeshi Kaneshiro), grizzled, bad-ass fighter Zhang Fei (Zang Jinsheng) and...what’s the name of the other warrior? The one who can’t save Liu Bei’s wife but saves his baby by tying the kid to his back so both hands are free to fight off a half-dozen of Cao Cao’s soldiers? That’s a cool scene. Love the way he says to the baby, “Wo men zou” (literally: “We go”) before the fight begins. But in protecting the peasants, Liu Bei loses the battle and his army heads south where... Wait a minute. Only now, when Kong Ming shows up hat-in-hand, does Sun Quan consider rebelling against Cao Cao? I thought he was already doing it. And yet in this scene he’s still dithering. In fact he leaves the final decision to his viceroy, Zhou Yu (Tony Leung) at Red Cliff, but at least that’s the title of the film, and at least that’s the star of the film, so hopefully we’ll stay put and won’t have so many new characters to memorize. Ah, no such luck. Even here we’re introduced to the he spunky younger sister of Sun Quan, Sun Shangxiang (Wei Zhao), an ex-pirate named Gan Xing (Shido Nakamura), and Xiao Qiao (Lin Shiling), the wife of Zhou Yu, who seems delicate and self-satisfied in that annoying way of Chinese cinematic heroines (pouring tea, practicing calligraphy), and who may be the real reason Cao Cao pushed for battle in the first place. Cao Cao saw her once when she was a child, and even then she was beautiful, but did he really engage his million-man army against these rebel provinces for her? And why is his name pronounced “Chao Cao” when it’s spelled “Cao Cao” in the subtitles? And why is Kong Ming listed on IMDb as “Zhuge Liang”? That’s not even close.

OK, so Cao Cao (Zhang Fengyi) is an imperial minister/general who intimidates even the Emperor of the Han dynasty into getting what he wants, which is full-fledged battle against rebel warlords Liu Bei (You Yong) and Sun Quan (Chang Chen), and a battle quickly ensues against Liu Bei’s army, which includes master strategist Kong Ming (Takeshi Kaneshiro), grizzled, bad-ass fighter Zhang Fei (Zang Jinsheng) and...what’s the name of the other warrior? The one who can’t save Liu Bei’s wife but saves his baby by tying the kid to his back so both hands are free to fight off a half-dozen of Cao Cao’s soldiers? That’s a cool scene. Love the way he says to the baby, “Wo men zou” (literally: “We go”) before the fight begins. But in protecting the peasants, Liu Bei loses the battle and his army heads south where... Wait a minute. Only now, when Kong Ming shows up hat-in-hand, does Sun Quan consider rebelling against Cao Cao? I thought he was already doing it. And yet in this scene he’s still dithering. In fact he leaves the final decision to his viceroy, Zhou Yu (Tony Leung) at Red Cliff, but at least that’s the title of the film, and at least that’s the star of the film, so hopefully we’ll stay put and won’t have so many new characters to memorize. Ah, no such luck. Even here we’re introduced to the he spunky younger sister of Sun Quan, Sun Shangxiang (Wei Zhao), an ex-pirate named Gan Xing (Shido Nakamura), and Xiao Qiao (Lin Shiling), the wife of Zhou Yu, who seems delicate and self-satisfied in that annoying way of Chinese cinematic heroines (pouring tea, practicing calligraphy), and who may be the real reason Cao Cao pushed for battle in the first place. Cao Cao saw her once when she was a child, and even then she was beautiful, but did he really engage his million-man army against these rebel provinces for her? And why is his name pronounced “Chao Cao” when it’s spelled “Cao Cao” in the subtitles? And why is Kong Ming listed on IMDb as “Zhuge Liang”? That’s not even close.

The movie didn’t need to be this much work. It clocks in at 2 1/2 hours but the original was twice as long, and released in two parts, over a six-month period, in Asia. Thus a lot of exposition has been removed, particularly, I assume, from the first battle, the Battle of Changban, with all of its peasants fleeing, etc. These cuts add to, rather than detract from, the confusion for western audiences. We’re introduced to too many characters too quickly, and not enough of it sticks.

I didn’t know I was watching a truncated version until after I’d watched it, and, of course, I immediately felt cheated—in the same way I felt cheated when I found out that the pre-“Sgt. Pepper” Beatles LPs I listened to in the states weren’t the same ones the Beatles produced and released for British audiences. At least there I knew enough to blame the greedy bastards at Capitol Records, but who to blame here? Summit Entertainment, the international distributor? Magnet Releasing, the genre arm of Magnolia Pictures, which was the U.S. distributor? Was it a western decision or an eastern decision? Or did the twain meet? Businessmen, after all, speak an international language. Worse, while cutting so much, they still added footage. That scene in the beginning where Cao Cao intimidates the Han Emperor? That’s for westerners. Its use of sudden, extreme close-ups, indicating extreme emotions, is right out of schlock 1970s-era Hong Kong cinema, and, initially, I assumed John Woo meant it as homage. But did he even direct this additional scene? Now everything is in question.

Despite all of that, “Red Cliff” is worth watching. It might even be worth seeing this bowdlerized version even if you plan on someday, somehow, seeing the uncut Asian version. The movie is truly epic.

Its story is as simple as any in Hollywood. A group of benevolent underdogs take on a corrupt, brutal establishment, and, against impossible odds (a 50,000-man army vs. a million-man army), win. And it’s true? No wonder they keep retelling it.

In fact, this is how popular the underdog story is: Even when they don’t need it, they use it. In the second battle of the film, in which Sun Shangxiang lures Cao Cao’s army into Kong Ming’s elaborately devised tortoise defense—where soldiers, hiding behind almost-man-sized shields, are placed in the pattern of an intricate tortoise shell, trapping and dispatching those lured inside—even here, rather than having the many (the good soldiers) slaughter the few (Cao Cao’s soldiers), the many stay in formation and let the superlative few—Zhang Fei, Gan Xing, Zhao Yun, Zhou Yu himself—take on dozens at a time. It’s tough letting go of the underdog motif.

As cool as these battle scenes are—and I particularly like Zhou Yu yanking an arrow from his shoulder, running at the horse-bound archer, and then spinning and plunging the same arrow into the back of the archer’s neck—my favorite moments in the film are how the two sides strategize. Woo cuts between the solitary general, Cao Cao, matching wits from afar with the group dynamic of, mostly, Kong Ming and Zhou Yu. Will Cao attack by land? What’s the best way to get 100,000 free arrows? Early on, Kong Ming dispatches Sun Shangxiang to spy for him and she sends back word, via pigeon, that Cao’s men are dying of typhoid...just as these dying or dead men are sent down the Yangtze, on rafts, by Cao, so that the peasants and soldiers on Kong Ming’s side will strip the bodies of valuables and catch typhoid themselves. Pretty smart. Cao is a worthy adversary. That’s part of the fun of the film. The typhoid epidemic even leads to the withdrawal of Liu Bei and his army. Meaning Sun Quan’s men were basically lured into a war and then abandoned. Meaning now the odds are worse. Meaning they’re even bigger underdogs than before. Let the final battle begin.

How many genres are included in this one movie? It’s obviously a war movie. It’s also a martial arts movie, since Zhao Yun, Zhang Fei, Gan Xing, and Zhou Yu are all masters. And don’t forget romance. Xiao Qiao is a kind of Helen of Troy here. She’s the face that launched a thousand CGI ships down the Yangtze River.

Weather plays a key role in each battle, and Kong Ming either reads weather well or controls it. To get 100,000 arrows, they need fog and they get fog. For the final battle, they need the winds to shift and the winds shift. They also need an elaborate tea ceremony, which is where Xiao Qiao, who turns up at Cao Cao’s camp at this key moment, comes in. She’s carrying Zhou Yu’s child, and one wonders if they will come to the same fate as Liu Bei’s wife and child at the beginning of the movie. Can both survive this time? Neither? Xiao Qiao has hinted that the child will be named Ping An, meaning “peace,” and so the question of their survival is also metaphoric. Will peace be born after the final battle?

Epics are tough to do (see “Pearl Harbor,” “Troy,” “Australia") but John Woo, whom Hollywood wasted, pulls it off spectacularly with his first Asian film in 15 years. He gives us a worthy melodrama, featuring interesting, boldly-drawn characters, on a wide and expansive canvas. The main characters aren’t dwarfed by the canvas and the canvas doesn't seem irrelevant because of our focus on the main characters. There’s balance between the two.

Here's an example of that balance. This is how Zhou Yu is introduced, and, to me, it rivals the great character introductions in movies. Before the two rebel armies have been unified, Kong Ming and Zhou Yu sit before Zhou Yu’s army, and the former watches them display, in that expert, martial-arts manner, this formation and that formation. “The goose formation,” Kong Ming whispers to a compatriot. “Unfortunately outdated.” He seems worried. Zhou Yu, whom we haven’t seen yet in full view, overhears his comment and seems annoyed. Nearby a boy plays a flute. Everyone stops and listens. Everyone is mesmerized. Everyone but Zhou Yu. His seat is now empty save for his goose-feather fan, and suddenly, quietly, he’s standing before the boy, holding out his hand. “Gei wo,” he says. (“Give it to me.”) The boy does. Then Zhou Yu takes out a knife...and carves a slightly bigger hole at one end of the flute and hands it back. The higher pitches were slightly off.

I would’ve liked more of this. Thankfully there is more.

Monday November 30, 2009

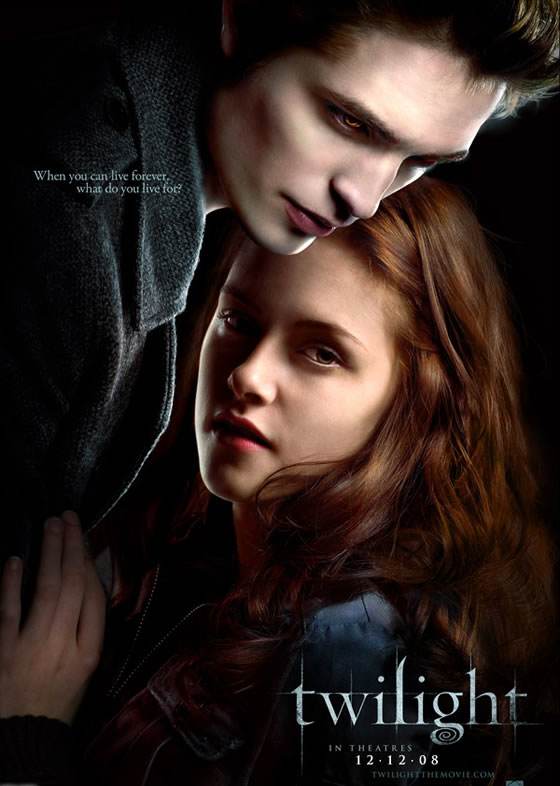

Review: “Twilight” (2008)

WARNING: AWKWARD, LONGING SPOILERS

I actually know Forks, Wash., or towns like Forks, Wash., since Patricia’s mom used to live in Joyce, Wash., further north and east on the Olympic peninsula. We used to go there every August for the Blackberry Festival. Patricia’s mom organized the local art show at The Grange, Patricia’s brother, Alex, a marine biologist from Port Townsend, was sometime-judge in the blackberry pie contest, and Patricia herself sometimes helped out at the cotton candy stand. The highlight was always a noon-time parade down main street, or the only street, Agate Beach Road, filled with vintage '30s cars and vintage '30s men (VOFWs) and usually something high-schooly. We watched near the Joyce General Store, which sold candy I thought ceased to exist in 1968. There were no vampires.

But it’s a brilliant conceit that a vampire clan would hang out on the Olympic peninsula to avoid the sun—which, in this universe, doesn’t destroy them but merely turns their skin all sparkly. The peninsula also works as a hangout for the Cullens because, well, it’s isolated, there’s game in the forests, and it’s already full of weirdos. The peninsula’s the place Washingtonians go when Walla Walla gets too crowded.

But it’s a brilliant conceit that a vampire clan would hang out on the Olympic peninsula to avoid the sun—which, in this universe, doesn’t destroy them but merely turns their skin all sparkly. The peninsula also works as a hangout for the Cullens because, well, it’s isolated, there’s game in the forests, and it’s already full of weirdos. The peninsula’s the place Washingtonians go when Walla Walla gets too crowded.

Bella (Kristen Stewart), our heroine, arrives in Forks from Phoenix, Ariz., cactus in hand, in March, because her mother and her new husband, Phil, are heading to Florida for spring training. Phil, according to the mother, is “a minor league baseball player.” Since Bella is 16 or 17, her mother would have to be, what, 32-35 at the youngest? Which means she’s either a cougar (to go with the Native American wolf packs), or Phil needs a new job. Generally if you don’t make the bigs by 30 you don’t hang around.

For a new girl in town, Bella does surprisingly well. In fact, she has to do little. Her father gives her a truck, the kids flock to her, she’s popular just by sitting there and, um, not knowing what to say or, um, maybe not caring what to say. The other kids fill her in on the Cullens, who seem good-looking and aloof, like Duran Duran in 1983, and she and Edward Cullen (Robert Pattinson) exchanged slow-motion, smoldering looks, like they’re in a “Hungry Like the Wolf” video. She also winds up sitting next to him in biology class. Biology. At first he ignores her, can’t seem to stand the smell of her, but then he’s charming and curious, and before you know it they’re in love, and before you know it she figures out that he, and all of the Cullens, are vampires. It takes about a week? Doesn’t say much for the rest of the folks in Forks, does it? Or do they already know and accept it as part of the usual peninsula weirdness? “Cassandra Starlight here used to be named Peggy Jones until she hit 54 and decided to change it, Zeke’s got a bumper sticker on his pickup saying ‘My real president is Charlton Heston,’ which he put on during the Bush years, and Dr. Cullen and his family? Well, they’re vampires. But kindly folk.”

It's been much-written, but, yes, Edward is the dream boyfriend for teenaged girls who are curious about but afraid of sex: He and Bella can’t have it because he might lose control. He might literally want to tear her apart. So romantic! There’s also a “gift of the magi” quality to their relationship: She loves him enough to become a vampire, he loves her too much to make her one, and so there they are, staring into each other’s eyes, longing. If anticipation is greater than consumption (see: “The Tao of Pooh”), then theirs is one great relationship. But it’s still a teenaged relationship, and, even though he’s a 100-year-old teenager (he became a vampire during the influenza outbreak of 1918), it’s full of awkward, teenaged conversations. Let me speak for the adults in the audience: Thank you for those moments when the camera pulls back, the music wells, and we just see them talking. It's lazy writing, sure, but still appreciated.

What else about Edward appeals to teenage girls? Basically he’s James Dean (the brooding, handsome, tortured loner) but superfast and superstrong and with the ability to read everyone’s mind but hers. So she’s as much mystery to him as he is to her. She’s mysterious and he’s curious. One wonders if that’s why he loves her in the first place. If true, it seems like an unromantic reason to me. I only love you because I don’t know you.

Their relationship also allows her, for all her spirit, to be the damsel in distress. No ass-kicking girl here. The good and bad vampires, the wolf packs, could tear her apart before she could blink so she gets to be rescued without guilt. Feminists, of course, are up in arms, but is this the secret desire of girls, as rescuing (particularly if you’re superstrong) is the secret desire of boys? This is not to discount lines like Edward’s: “I don’t have the strength to stay away from you anymore.” I know that has its appeal, too.

The movie does a good job with the locale, by the way. The kids go to La Push and Port Angeles, they reference Kitsap County sheriffs, and the men drink Rainier beer and watch Mariners games. There's a lot of cloud-cover and drizzle. It’s all very Pacific Northwesterny.

“Twilight” isn’t as horrible as I thought it’d be and it’s kind of fun to watch with a girl, or even a woman, to see what she likes about it. That should be its appeal for boys. Most of us are like Edward—we have no clue what you’re thinking—but the big question is if “Twilight,” by giving us that clue, is helpful, or just slowly, vaguely horrific.

Saturday November 21, 2009

DVD Reviews: 1 Win, 1 Loss, 1 Tie

I‘ve been down with a cold for the last five days and wimping out when it comes to movie choices. Last week Patrick Goldstein mentioned that when he’s sick, which he is, with the H1N1 virus, he goes for the comfort food of old John Wayne westerns. Not sure what my cinematic comfort food is. Woody Allen? Bogart? I nearly watched “The Insider” again last night but instead went with “Visions of Lights,” the 1992 documentary on the history of cinematography, since I didn't know if I could last the length of “The Insider.” BTW: I'd love to see an expanded version of “VoL.” I could watch cinematographers talking about their craft a good while longer.

I‘ve also been catching up with a few cinematic also-rans from this past year that, if I weren’t sick, I probably wouldn't have bothered with. As I said: wimping out. Wasn't as bad as I thought: 1-1-1:

- The Win: The Taking of Pelham 123, with Denzel Washington and John Travolta. Didn't do particularly well with critics (53% from the-ones-who-matter), and did equally so-so with audiences (opening third, behind “The Hangover” in its second week and “Up” in its third, with $23 million, on its way to $65 million domestic—which, by the way, is less than “New Moon” took in yesterday). Jeff Wells over at Hollywood Elsewhere, a fan of the new “Pelham,” has been thrashing around ever since at the idiocy of both critics and audiences. He even recently recommended it for best pic. I wouldn't go that far but it's a good movie: tense, fun, surprisingly relevant. The critics probably turned against it in comparison with the ‘73 version, and that was certainly my reaction upon seeing the trailer in May. I wrote: “I’m a fan of the original, so this hypercharged version, with cars crashing and malevolent, tattooed villains spouting threats, just makes me feel sad and wish for 1973 New York.” Which may have been the problem, box-office wise: the car crashes were designed for kids, the actors for adults, and the twain didn’t meet. It also loses me near the end—you‘re a civil service dude, Denzel!—but it’s a good movie with solid, fun performances. Not best pic but worth renting. Put it this way: It's fun watching actors acting.