Movie Reviews - 1930s posts

Monday January 31, 2022

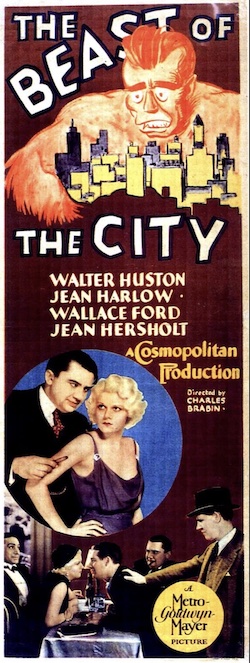

Movie Review: The Beast of the City (1932)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The first half is ur-“Dirty Harry.” Walter Huston plays Jim “Fightin’” Fitzpatrick, a tough-as-nails cop who will do anything to clean up this dirty city, damnit, and who is thus forever in trouble with the higher-ups and the press. Some of his lines are straight out of the Clint Eastwood playbook. “What do you expect me to do with gunmen, dope peddlers, and sneak thieves—kiss ’em on the forehead or slap ’em on the wrist?” Fitz says. Eventually he’s shunted off to a dull, nothing post, where they figure he can’t do any harm.

The second half is “Blue Angel”-lite. Fitz’s younger brother, Ed (Wallace Ford), falls for the sexiest moll in town, Daisy Stevens (Jean Harlow), and keeps falling and falling. She gets him involved in drink and crime. She corrupts and ruins him. And when big brother comes back as police captain to clean up this dirty city, damnit, and is too honest to give his brother a sinecure, the kid, pushed by Daisy, works with the big gangster in town, Sam Belmonte (Jean Hersholt, of the humanitarian award), to rob a bank-delivery truck. It leaves three dead: a robber, a cop, a little girl.

The second half is “Blue Angel”-lite. Fitz’s younger brother, Ed (Wallace Ford), falls for the sexiest moll in town, Daisy Stevens (Jean Harlow), and keeps falling and falling. She gets him involved in drink and crime. She corrupts and ruins him. And when big brother comes back as police captain to clean up this dirty city, damnit, and is too honest to give his brother a sinecure, the kid, pushed by Daisy, works with the big gangster in town, Sam Belmonte (Jean Hersholt, of the humanitarian award), to rob a bank-delivery truck. It leaves three dead: a robber, a cop, a little girl.

“Beast of the City” is not a good movie but it’s got moments. It opens well with a tracking shot of calls coming in and being dispatched to cops around the city. Most of the calls are inconsequential and/or humorous until we get to a murder: four men hung in a basement warehouse. The dead are gangsters, Fitz suspects Belmonte and drags him in without evidence. And we’re off and running.

The movie is most intriguing today for its by-the-way racism. From the hero. When two good cops, Mac and Tom (Sandy Roth and Warner Richmond), volunteer to follow Ed on his ill-fated assignment, Fitz smiles and tells them: “That’s mighty white of you guys.” It’s not a one-off, either. Near the end, Fitz is interrogating one of the men behind the heist, Abe (Nat Pendleton), and goes off on him. “You forgot to tell me about shooting a little girl down in the gutter! You forgot to tell me about killing one of the finest white men that ever lived!”

A cop obsessed about race. Glad we got over that.

Hoover Mayer ’32

The movie opens with a quote from Pres. Herbert Hoover:

Instead of the glorification of cowardly gangsters, we need the glorification of policemen who do their duty and give their lives in public protection. If the police had the vigilant, universal backing of public opinion in their communities, if they had the implacable support of the prosecuting authorities and the courts, I am convinced that our police would stamp out the excessive crime which has disgraced some of our great cities.

It’s taken from a speech Hoover gave in October 1931 before the International Association of Police Chiefs, so initially one assumes MGM and Cosmopolitan Productions (William Randolph Hearst’s outift) simply tacked on the quote to give their film gravitas—a presidential seal of approval, as it were. But there was more at work here. Louis B. Mayer was friends with, and an active supporter of, Hoover, and several sources (here and here) say that Hoover and Mayer talked about “the need to educate the public to have a greater respect for law enforcement officers.” So were they working in lockstep? I’ll give the quote, you make the movie? It certainly benefitted both men. The president of the United States got to attack lawlessness and Mayer got the president of the United States to attack Warner Bros.

Huston played a lot of stern authority figures in the early 1930s, didn’t he? Missionary, judge, warden. He played one of the first screen Wyatt Earps, dubbed “Saint” Johnson, in “Law and Order,” as well as two presidents of the United States: one fictional (“Gabriel Over the White House”), one historical (“Abraham Lincoln”). Some of his sterner roles, as this one, veered toward the fascistic. It’s an interesting heyday for an actor whose best-known scene today is laughing and dancing a jig in the dusty Mexican mountains.

He’s a family man here, too, with two comic-relief daughters (they try to make him pancakes), a younger son in on the joke (Mickey Rooney, quite good), and a dull, supportive wife, (Dorothy Peterson of “Mothers Cry”). Unlike city homes in Warner Bros. movies, their home already seems suburban. You feel like it could’ve been the set of a 1950s TV sitcom.

The big question for most of the movie is how far Ed falls. The answer turns out to be “all the way,” and when Fitz finds out Ed was part of the gang behind the heist, he has him arrested, too. Belmonte figures the best way to get back at Fitz is to get his men off, so we get courtroom scenes in which the truth is garbled and witnesses and jurors have obviously been threatened and/or bought off. MGM was big on these. It’s basically the same as in “The Secret 6,” MGM’s gangster flick from the year before, right down to the judge (Murray Kinnell) chastising everyone involved. “I see your hearts are made of water,” he says.

Afterwards, we get an odd scene of Fitz siting alone in a dark room, sweating and in obvious emotional pain, when someone enters. “Is that you, Tom?” Fitz asks, referring to one of his good cops (Warner Richmond), but he almost sounds panicky. Then it cuts to a different take, where Fitz is less sweaty and more in control of himself. “Who’s there?” he asks sternly. Turns out it’s his brother, contrite, but Fitz is unforgiving. “You sold the whole town into his greasy hands,” he says.

This is when he comes up with the worst plan in the world. He tells Ed to go to Belmonte, who’s partying with his pals, and say he’s going to confess, which will force Belmonte’s hand. Fitz and his men will then show up. And it works. Belmonte’s hand is so forced, in fact, it leads to a shoot-out, almost Old West style, in which the lawmen walk slowly forward with guns blazing. What happens? Everyone dies: good cops with bad gangsters, Ed and Harlow (balcony, stray shot), Belmonte and Fitz, who, as the movie fades, reaches and touches his brother’s dead hand before expiring himself.

It’s supposed to be a great self-sacrifice. But it’s so unnecessary, such a lousy plan, that one wonders if our hero should’ve been the hero in the first place.

For some reason, they all wind up dead.

Scanditalian

The movie’s screenwriter was the legendary W.R. Burnett, who wrote the novels on which “Little Caesar,” “High Sierra” and “The Asphalt Jungle” are based, and whose screenplays included the original “Scarface” with Paul Muni and “The Great Escape” with Steven McQueen. Helluva career. Basically the man helped create the gangster film, and then helped recreate it as film noir. In “Backstory: Interviews with Screenwriters of Hollywood’s Golden Age,” by Patrick McGilligan, he’s amusing on this film:

Who directed that?

Charles Brabin, an Englishman. Everything about it was wrong. Making an American hoodlum picture, giving it to an Englishman. We’d have a story conference and he’s go to sleep right in your face.But Brabin did a good job directing?

Strangely enough, he did.

He also thought that while there were no good Al Capone-type pictures, this one was pretty good, and that “Hersholt was a greasy, offensive Capone.” Respectfully, no. Hersholt makes a ridiculous gang leader—Italian with a Scandinavian accent. His right-hand man, Pietro Cholo (J. Carrol Naish, who would play every ethnicity over the years), seems way more dangerous. As does Harlow. Belmonte just seems comic, not much of a threat at all, but in the logic of the film he runs the city.

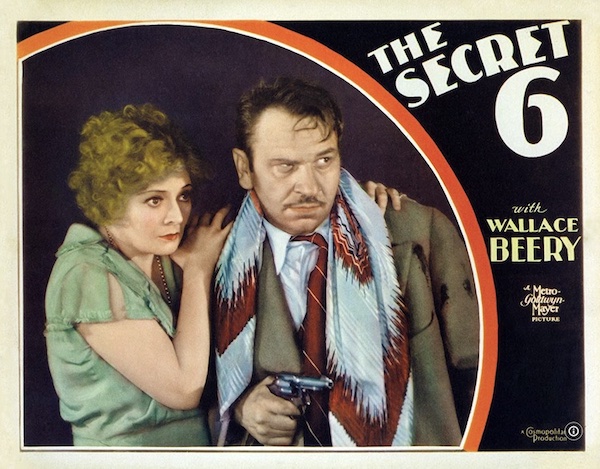

The movie’s working title was “City Sentinels” but MGM went with something more sensationalistic. Some irony: Its earlier film, “The Secret 6,” focuses on the Al Capone-like gangster (Wallace Beery) even though the title highlighted the movie’s little-seen sentinels, while this one focuses on the city sentinel but its title highlights the little-seen Al Capone-like gangster. Further irony: the movie that was all about glorifying cops gave title credit to the bad guys. Maybe MGM decided that's where the money was.

“Good ol' days.”

Saturday January 15, 2022

Movie Review: The Secret 6 (1931)

The requisite gangster poster of the era. Whither Harlow?

WARNING: SPOILERS

This was MGM’s foray into the world of gangster movies after the sudden success of “Little Caesar” and the adjacent anticipation of “The Public Enemy,” which was being made concurrently. (Filming Jan-Feb. 1931, release in April-May.)

It’s another Al Capone knockoff. Louis Scorpio (Wallace Beery) is nicknamed “Slaughterhouse” because of where he works and what he does. He’s in the Chicago stockyards and he’s good at killing things. That’s not a bad idea: translate the killing of one kind of meat (cattle) into another (human beings). But the filmmakers, including the husband-wife team of director George W. Hill and screenwriter Frances Marion, don’t do enough with it. And there are tons of missed opportunities.

Let’s just say it’s not exactly Warner Bros.

Like Georges Méliès

One day after work, Slaughterhouse meets his friend Johnny Franks (Ralph Bellamy, in his film debut) for dinner. Franks is a low-level gangster in the Centro district (read: Cicero); and while Scorpio is impressed with himself for his $35 weekly take, Johnny rolls out the $150 he made while hardly breaking a sweat. Plus he’s got Peaches (Marjorie Rambeau) hanging around making nice with him—and decidedly not with Scorpio, whom she refers to as a “missing link.”

At this point Scorpio is an affable, milk-drinking dude, with disheveled hair, a short tie and a rumpled suit. Then he spends a night with Johnny. It’s not a huge success. Johnny threatens Delano (Fletcher Norton) for selling bootleg liquor to rival gangster Joe Colimo (John Miljan) when the cops burst in. Our guys lam it and wind up at the law offices of Richard Newton (Lewis Stone, Andy Hardy’s dad), who’s drunk behind his desk, but who assures them everything is under control. Eventually we realize Newton isn’t consigliere; he’s the gangleader. It’s hard to tell because of poor filmmaking, but his his law office is above Frank’s Steakhouse, a gang hangout, which will matter later.

Again, hardly a successful night, but Slaughterhouse is hooked. So after a montage of generic booze-making and selling, we see him cleaned up, in bowler hat, trim moustache and three-piece suit. He’s still a milk drinker (that doesn’t change) but he’s no longer affable. He’s impatient, irritable, and butting heads with Johnny, who now sees him as his main rival. So when Newton’s plot to take over Colimo’s territory goes awry, resulting in the death of Colimo’s perpetually smiling kid brother, Slaughterhouse is set up. Instead they just wing him, and when he returns to Newton’s office he finds his milk bottle metaphorically dropped in the wastebasket. “Didn’t you … expect me back?” he asks, before plugging Johnny from behind.

Here’s how cheaply or on-the-fly this movie was made. After the plugging, and after Newton talks Slaughterhouse down, there’s suddenly a third man in the room: Delano. It’s almost like a magic act—like something from Georges Méliès. Not there. Poof! There. Either the filmmakers forgot they needed a fall guy and added him without reshoots, or they cut the scene where he arrives. Either way, it’s odd.

After that, Slaughterhouse is all-powerful. He taps a flunky gangster to be the next mayor of Centro, then makes inroads into Chicago. And that’s when we see our titular group.

Who are the Secret 6? They’re powerful Chicago businessmen who fight back against mugs like Slaughterhouse. How do they do it? They gather in rooms wearing masks like Robin the Boy Wonder. And? And that’s about it. To be honest, they reminded me of something out of a Republic movie serial—those ineffective businessmen gathering in the same room for 12 chapters. They don’t do anything—until, with eight minutes left, they suddenly get their act together and announce the following:

- The feds will charge Slaughterhouse and his gang with fraudulent income tax returns

- Also arson

- Also, they’ve got deportation warrants for half of them

- Also, Newton will be disbarred

Nick of time.

Here’s an odd chronological tidbit: According to AFI, the movie was filmed in January and February 1931, and according to Wiki, the arrest of Al Capone on income tax evasion charges occurred on March 13, 1931. So did they anticipate the arrest of Capone on income tax charges? Was it already being bandied about in the press?

Half of our titular heroes.

Throughout the film, we also follow two reporters who jaw good-naturedly with each other and come to regret giving Slaughterhouse so much copy: Hank Rogers (Johnny Mack Brown) and Carl Luckner (Clark Gable). Both men vie for the attentions of Anne Courtland (Jean Harlow), the girl who works the cash register at Frank’s Steakhouse.

This is apparently the movie that got Gable his MGM contract. AFI again:

According to a biography of Irving Thalberg, the producer initially cast Clark Gable in a small role, but as filming progressed new scenes were added to bolster his part. The result was a screen presence three times longer than that called for in the original script.

You get why, too. He just pops. He seems real, natural and sexy. Here he is talking to the new girl behind the cash register at Frank’s:

Carl: Hello honey, where did you come from?

Girl: The stork brought me.

Carl: Oh yeah? (pause, smile) Wish he’d bring me one.

Gable, lighting up the screen, about to play a Mills Two Bits Dewey Jackpot slot machine.

It’s the first screen pairing of Gable and Harlow, who would heat up the pre-code era, but it’s Hank who wins Anne. Then Hank runs into trouble with the gang and is shot dead on the subway—an apparent nod to the gangland shooting of Chicago Tribune reporter Jake Lingle in 1930.

For that, Slaughterhouse goes on trial, but it’s a fiasco and Newton gets him off. MGM was a real rah-rah America studio but at this point they don’t seem to have much faith in the judicial system. A year later, in “The Beast of the City,” the exact same thing happens—right down to the judge chastising the jury. There, the judge tells them their hearts are made of water. Here, he intones: “In all my experience on the bench, I have never seen a more outrageous miscarriage of justice! Your verdict must remain as a blot upon the courts of this state!” Then all of a sudden the people are fed up, they crowd the gangsters and talk of lynching, but the bad guys get away. Which is when the Secret 6 get their act together.

Like Chief Bromden

Pursed by the cops again, Newton tries to take off with the dough but Slaughterhouse kills him. Then he tries to hide out with Johnny’s old moll, Peaches, who locks him in a closet and laughs until the cops arrive. Another missed opportunity. Peaches kind of disappears after Johnny’s death. A scene where she becomes moll to the repugnant Slaughterhouse, and where you see her helplessness, would’ve made this scene pop.

I almost get the feeling “Secret 6” was re-released in the post-code era, and scenes were cut and lost forever. Take Murray Kinnell (Putty Nose from “The Public Enemy”) as Metz, a man who pretends to be deaf and dumb. When did Slaughterhouse figure out Metz could hear and talk? It’s just suddenly there—like Delano in Newton’s law office. We do get a great shot of Slaughterhouse, in prison, watching the cops sweat Metz, and then the door closing on him. It’s very final shot of “The Godfather.”

The Secret 6 really did exist, by the way—sans Robin masks, one assumes. They organized to take on Al Capone and were dubbed “Secret 6” by the press in homage to the group that bankrolled John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry raid in 1859. Now there’s another Secret 6: a DC Comics superhero group, begun in 1968 and still around. Does that speak to the age or what? 19th century: Let’s end slavery. 20th century: Let’s stop Capone. Today: Let’s play with superheroes while the world burns.

Sweating Metz, one of the movie's most effective scenes but an underutilized character—not to mention character actor.

Monday January 10, 2022

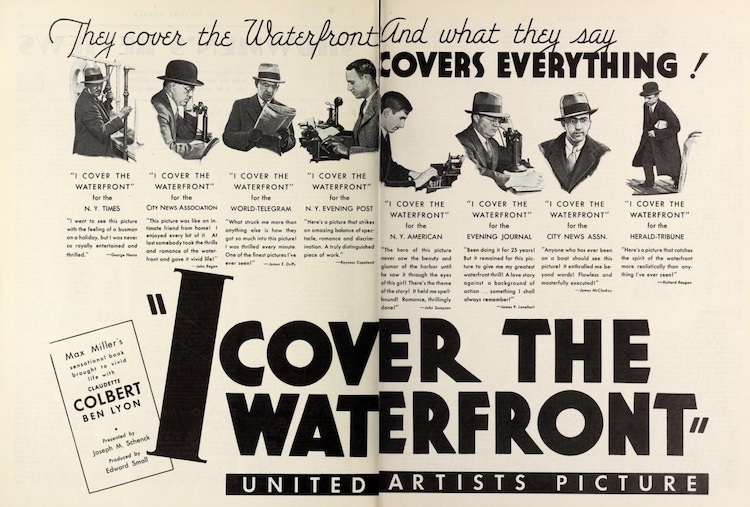

Movie Review: I Cover the Waterfront (1933)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This is a helluva find, a recently restored, pre-code Universal Studios flick that reminded me of Thomas Hobbes’s quote about life: nasty, brutish and short. In 72 minutes, it gives us murder, death by shark, over-the-top racism, and Claudette Colbert tied to a torture rack and forced to kiss the male lead. Don’t worry, she’s charmed by it.

It’s obviously drafting off of other movies, too. The title recalls Warners’ hit from the previous year, “I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang,” and we get elements of “The Front Page,” with reporter and editor forever bickering. But it’s its own thing.

Yellowtail

Joe Miller (Ben Lyon) is a carping reporter who hates his beat, the San Diego waterfront, but as long as he’s there he’s pushing to do a big story on a Chinese smuggling ring. Sadly, his editor, John Phelps (Purnell Pratt), waves him off to go after titillating stories like a girl who swims in the nude. Hey, turns out the girl, Julie Kirk (Claudette Colbert), is the daughter of the guy Miller thinks is behind the Chinese smuggling ring, Eli Kirk (Ernest Torrence). Nice coincidence. One of many.

Joe Miller (Ben Lyon) is a carping reporter who hates his beat, the San Diego waterfront, but as long as he’s there he’s pushing to do a big story on a Chinese smuggling ring. Sadly, his editor, John Phelps (Purnell Pratt), waves him off to go after titillating stories like a girl who swims in the nude. Hey, turns out the girl, Julie Kirk (Claudette Colbert), is the daughter of the guy Miller thinks is behind the Chinese smuggling ring, Eli Kirk (Ernest Torrence). Nice coincidence. One of many.

When I first heard about the Chinese smuggling ring, I assumed it was the Chinese doing the smuggling but they’re the ones being smuggled. It’s 50 years into the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882-1943), and illegal immigration is their only way into the country. Oh, and Miller is right: Kirk, a weatherworn fisherman, is the smuggler. “When you can’t make a living off tuna,” he says to his deckhand, Ortegus (Maurice Black), “you just as well might fish for yellowtail,” then nods toward a trussed-up Chinese guy on deck. He adds, philosophically, “You know, they ain’t bad folks. And somebody’s got to do the washing.”

Brace yourself. It gets worse.

I was trying to figure out why the Chinese guy was trussed up when the Coast Guard, with Miller on deck, steams toward them to search the vessel. Ah, so maybe they hang him off the side so he can’t be found? Nope. Kirk just puts chains on him and sinks him. Afterwards, he feels kinda bad about it but he still keeps the dude’s $700 and the beautiful Chinese robe it came wrapped in. Julie gets the robe.

Miller exchanges words with Kirk and shortly afterwards we get our nice big coincidence. Miller's next story is about an old trawler—a guy in a rowboat who dredges treasure from the harbor. And guess what he brings up?

Trawler: Well, son, this here chink didn’t put them there chains around his feet his self. … Looks like he was dunked. Seeing as he’s used to it, I’ll dunk him again.

Miller: Oh no, you don’t! This poor chink tried pretty hard to get in the United States. I’m taking him in. … Sell me this chink. He’s news!

Even with the dead body, the editor still thinks it isn’t a story. He thinks Kirk needs to be charged before it’s a story. So Miller decides to woo Julie to get inside info.

Now for our third coincidence. Miller and his pal, the perpetually drunk, perpetually grabby One-Punch McCoy (Hobart Cavanaugh, a kind of ur-Walter Brennan), are coming out of a speakeasy when they hear Kirk playing piano and singing in the speakeasy next door. Miller figures a drunk Kirk might spill the beans so in they go. Oddly, they never approach him. Instead:

- Kirk goes upstairs with a call girl

- Julie shows up

- Miller dances with Julie

- Julie sees her father has been rolled

- Julie beats up the call girl to get the money back

She might look like Claudette Colbert but she spent time on the mean streets of Singapore, baby.

As Miller tries to woo her, we get the best lines of the movie:

He: C’mon, let’s play a love scene.

She (dryly): Let’s fall in love first.

And later:

He: You wouldn’t go for that kiss now, would ya?

She: Say, I thought you came down here to work.

He: If you don’t think it’s work getting a kiss out of you, you’re nuts.

At that point, they’re on a tourist attraction, the prison ship Santa Madre, 25 cents. Which is how she gets tied up for the kissing scene. He even puts a belt around her neck so she can’t move her head. “Enough torture?” he asks after several go rounds. A big smile from Julie. “Mm-mm. I could take it.”

And that’s how she falls. Afterwards, we get lovey beach scenes and a pre-code evening together (his place, fadeout, breakfast). But they argue about the future. She loves San Diego, he talks up Vermont. So there’s a problem. Besides the fact that he’s pumping her for information to convict her father.

He finally gets the info: He’s told the old man is returning that evening to a Chinatown port after a shark-hunting expedition. But he wonders: Why hunt shark when the tuna are plentiful? Because you’re not really hunting shark! You’re really picking up Chinese in the south! So he alerts the Coast Guard.

Except Kirk was hunting shark, and those scenes, while primitive, are fascinating. Kirk’s boat seems a forerunner to Quint’s in “Jaws”; and when he and Ortegus go out on a rowboat and harpoon a big guy, they’re dragged along—again like in “Jaws”—and the rowboat goes under. Ortegus is attacked, loses a leg, dies. Did Steven Spielberg ever see this? Definitely feels like it.

All this time, though, we’re wondering, along with Miller, why Kirk is hunting shark, and back in port the Coast Guard find nothing—just the dead shark. Then One-Punch McCoy literally stumbles upon a fish in which Kirk has hidden a bottle of booze—we’d seen that in the first act—which makes the lightbulb go on above Miller’s head. And on the dock, Miller cuts open the shark and out spills a Chinese immigrant. Fleeing the cops, Kirk catches a bullet but escapes; Miller gets the headlines but feels awful for betraying Julie.

All that’s left are the final confrontations and reconciliations. Kirk finds a snooping Miller, shoots him, admits he’s a tough kid. Miller admits he gave Julie a raw deal while Julie admits to her father that she loves Miller. Being the good father, he helps save Miller’s life, then dies. And upon returning from the hospital, Miller finds his dingy room spruced up and Julie emerges from the bedroom all smiles.

As for the Chinese? 沒有了。

“Jaws” 1933

Billing

“I Cover the Waterfront” was based upon a book of the same name by Max Miller, a San Diego reporter, which was apparently so popular it led to a song of the same name, covered by everyone from Billie Holiday to Frank Sinatra.

The billing is interesting. Ben Lyon had been the star of Howard Hughes’ highly touted “Hell’s Angels” in 1930, even flying his own plane in the stunt scenes, and he was still a big-enough star to get top billing here; but he’s on the way down. Colbert, on the other hand, is about to shoot into superstardom with “It Happened One Night” and “Cleopatra” and remains a legend to this day. They’re movie stars passing in the night. You get why it happens, too. She’s effortlessly charming while he’s kind of brittle. She’s attractive while he’s OK. But what a fascinating life. In 1930, he married actress Bebe Daniels, the original Ruth Wonderly in 1931’s “The Maltese Falcon,” and the original Dorothy Gale in 1914’s “The Wizard of Oz”—she was also cousin to DeForest Kelley—and during World War II they lived in England, where they hosted a radio show, “Hi, Gang!” After the war, he became a casting director for 20th Century Fox and apparently suggested that a young actress named Norma Jean Baker change her name. Maybe to something alliterative. With MMs in it.

Third-billed Ernest Torrence was a 6’4” Scotsman who made his name as a silent-movie villain, playing, among others, Capt. Hook and Prof. Moriarity. He was the tough “Steamboat Bill” to Buster Keaton’s “Jr.” as well as King of the Beggars in Lon Chaney’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame.” He’s great, but this is his last movie. Four days after its premiere, he died—of gall stones, of all things. It feels like there was a lot of sudden deaths in Hollywood in the early 1930s.

Motion Picture Herald ad using the praise of waterfront reporters rather than critics.

Monday October 11, 2021

Movie Review: A Slight Case of Murder (1938)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This again?

I don’t mean Edward G. Robinson playing a gangster, since he was supposed to do that. He played eight of them between “Little Caesar” and this. I'm talking something more specific: Robinson, in a comedy, playing a gangster boss who tries to go legit after Prohibition is repealed in 1933 and runs into trouble.

In “The Little Giant,” from ’33, Robinson played “Bugs” Ahearn, who decides to take his Prohibition-era dough and scram to LA/Hollywood, and mingle with the jet-set there. The joke is he thinks he’s entering refined society but they’re actually bigger crooks than he is.

In this one, he plays Remy Marco, a Prohibition-era gangster who decides, after repeal, to keep selling his beer legally. The joke is he doesn’t know his beer sucks, and, with tons of legal options, no one will buy it. Thus: trouble.

In this one, he plays Remy Marco, a Prohibition-era gangster who decides, after repeal, to keep selling his beer legally. The joke is he doesn’t know his beer sucks, and, with tons of legal options, no one will buy it. Thus: trouble.

Runyonesque

“A Slight Case of Murder” is based on the play by Howard Lindsay and Damon Runyon—Runyon’s only theatrical production—which ran for 60 or so shows in the fall of 1935. It was basically contemporaneous with repeal so the “sucky beer” gag makes sense. Warner Bros. also makes “Slight Case” contemporaneous—but to the year it was released: 1938. Meaning Marco has been trying to sell his awful beer for five years? And no one’s told him? I had trouble getting past that.

- “Say, you mugs, why aren’t we selling anything?”

- “Well, the beer sucks, boss.”

- “What are saying about Marco’s beer?”

- “I’m saying it’s no good, boss.”

- Sips. Spits. “Say, you’re right! Why didn’t you tell me sooner?”

We get a scene like that but way, way too late. As a gag, I’ll buy his ignorance for a month or two. But five years? The gag loses its fizz and loses my interest.

That’s one aspect of the plot: Marco wheeling and dealing to keep the bank from seizing his brewery because he’s selling sucky beer and doesn’t know it. (Robinson is good, by the way, at drawing out the comedy of a man super confident in what everyone else knows is wrong.)

Marco’s financial troubles necessitate calling back his daughter, Mary (Jane Bryan), from her studies in France, and they all decide to meet at their Saratoga home in Upstate New York. And she’s got news: She’s engaged to the well-heeled Dick Whitewood (Willard Parker), who, feeling he should have some kind of job, gets one with the police. But his attempts to introduce himself at the Saratoga home are constantly rebuffed by Marco and his gang (Allen Jenkins, Edward Brophy, Harold Huber, an All-Star assemblage of Warner Bros. character actors), who assume he’s just another cop hassling them.

Remy brings with him an orphan from his former orphanage—a kid named Douglas Fairbanks Rosenbloom, played with “so’s your old man” charm by Bobby Jordan, one of the original Dead End Kids. Oh, and before they arrive, the nearby racetrack is robbed and the five crooks are hanging out with the dough at Marco’s home, upstairs, until one of them, the oddly named Innocence, panics and shoots the other four.

All of this, plus Whitewood’s uptight dad at Marco’s boisterous party, set the stage for madcap antics and misperceptions. You can definitely see the play in it. Once we arrive in Saratoga, I don’t think we move from the home.

Slight

I like the idea that finding four dead bodies upstairs isn’t a big deal for these gangsters, as it would be for most of us. In fact, they put the bodies to good use by depositing them on the doorsteps of Marco’s enemies. But once the gang finds out there’s a reward, dead or alive, the bodies are retrieved and stuffed in a closet upstairs.

Amid the chaos, order of a kind is restored. Marco uses the stolen racetrack money to convince the bankers he’s flush, so they extend his mortgage and his brewery is saved. He convinces his future son-in-law that the dead gangsters in the closet are alive and has him shoot them—and the kid becomes a hero in the process. A stray bullet from his jittery hand kills Innocence. The movie ends abruptly with Marco fainting at the news.

A standout is Ruth Donnelly as Marco’s wife, Nora, who is forever forgetting to put on airs and keeps returning to her plain-talking patois. But “A Slight Case of Murder” is just that: slight.

Thursday September 23, 2021

Movie Review: Kid Galahad (1937)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This one’s a bit odd: Warner Bros. pairs two of its biggest stars in a movie that isn’t really about them.

It’s also not odd at all, since each actor becomes what they generally become in a Warner Bros. movie. Edward G. Robinson gets spurned by his woman, as so often happened, and then dies of a gunshot wound, as ditto; and Bette Davis, who did the spurning, exits the boxing gym at the end and walks out into the chill of the night, alone, forever alone, which is classic Bette.

It’s also not odd at all, since each actor becomes what they generally become in a Warner Bros. movie. Edward G. Robinson gets spurned by his woman, as so often happened, and then dies of a gunshot wound, as ditto; and Bette Davis, who did the spurning, exits the boxing gym at the end and walks out into the chill of the night, alone, forever alone, which is classic Bette.

“Kid Galahad” is directed well by Michael Curtiz, and the boxing scenes are powerful for the period—the camera is right in there with them—and the cinematography is beautiful black and white. But I lost interest halfway through.

They're dull, he's dumb

Robinson plays Nick Donati, an irascible boxing manager ready to fire any fighter who doesn’t follow his orders to the letter, while Bette is his girl, “Fluff,” who’s the brains of the operation, always figuring out ways to smooth things over.

Yes, That’s right: They cast Bette Davis as someone named Fluff. One wonders if Jack Warner wasn’t punishing her for her recent contract disputes.

The movie opens with a boxing match in Miami:

How often do boxing managers get billed above the fighters? One assumes: never?

Donati’s fighter, Burke, doesn’t follow the game plan, loses, so Donati cuts him loose. On the cabride back to the hotel, Donati asks Fluff how much they lost that night ($17,300) and what they have left ($1,800). “We might as well shoot it on a party and start over.” Cut to: the third day of the shindig, when Fluff is serving drinks because the hotel bellhop passed out drunk (hotel bellhops mix drinks at private parties?). So Donati orders up a clean-cut bellhop. He gets one. And how.

Ward Guisenberry (Wayne Morris) is tall, blonde, broadshouldered, and innocent as a lamb. All the women make innuendo with him and/or passes at him, and thus all the men resent him. Donati’s rival, Turkey Morgan (Humphrey Bogart), says he’s too cute to wear long pants and cuts off his pant legs below the knee with a knife. When Fluff tries to intervene, Morgan’s fighter Chuck McGraw (William Haade), a heavyweight contender, pushes her around. So the bellhop decks him. And a lightbulb goes on for Donati.

Well, a light bulb goes on for us; we’ve seen this movie before. Donati is a tougher sell. He agrees to manage the bellhop in a boxing match with McGraw’s brother because he wants him to get a beating, too. He’s jealous of how much Fluff likes him. Basically he’s siding with Turkey Morgan even though he’d just learned Morgan paid off Burke to take a dive. Makes no sense.

Yet Fluff does fall for the kid. I think it happens when she’s walking him to the elevator after the pants-leg incident and he admits he didn’t know what he was getting into. “That’s the first time I’ve ever seen anyone hit a lady,” he says. Her response is delayed. She measures what he says, then realizes she’s the lady. I think that’s when she begins to fall. Nice bit of acting.

Of course, the kid beats McGraw’s brother, Fluff dubs him Kid Galahad, and Donati realizes he might have something here. But since Turkey’s such a sore loser, Donati has to stash him at his mother’s farm upstate—with the added admonition that he stay away from, Marie (Jane Bryan), his recently cloistered sister. Though they initially toss barbs at one another, anyone can read the writing on the wall. That’s actually when I began to lose interest. I was hoping Bette would win the boy. I’d completely forgotten the point of Bette Davis is to wind up alone.

So Galahad rises, Fluff falls (when she realizes Galahad loves Marie), and Donati falls harder (when Fluff leaves him). But it’s all played out against irrelevance—that Galahad shouldn’t k.o. this boxer because it means a title shot too soon, etc. It feels like there’s a cleaner, harder story here, about a man who takes on a fighter for the wrong reasons and then loses everything that’s important to him: his woman and his sister. Or maybe it should be more comic? Hey, stay away from my sister and my woman. Either way, too much of the movie’s focus becomes the kids, who are dull things. Plus Fluff gets dull after she leaves Donati to sing torch songs in a nightclub, while Donati’s never smart enough. Seriously, he’s about the dumbest movie fight manager I’ve ever seen. He has a kid who has the stuff to be champion but never recognizes it: not at the beginning, when he wants him to get a pummeling, and not at the end, when he bets against him in the title bout vs. McGraw, and then feeds him bad advice. It’s never about the fight.

1-1-2

“Kid Galahad” did well at the box office and with the critics. Bette, a tough critic herself, talked highly of it in her autobiography, and it’s still sporting a 7.2 rating on IMDb. It was remade with Elvis in the early ’60s, while “The Wagons Roll at Night” from 1941 is apparently another version, albeit set in a circus, with Bogart in the Robinson role. It’s his last movie before he officially became Bogart; his next role was “The Maltese Falcon.”

According to IMDb, Bogart and Robinson made five movies together, and in only one of them, “Brother Orchid,” do both survive. The tally otherwise is: Robinson kills Bogart (“Dr. Clitterhouse”), Bogart kills Robinson (“Key Largo”), and they both kill each other (“Bullets or Ballots” and this one). So 1-1-2.

Here, because Donati tells Turkey what he’s up to with the title match, Turkey bets a wad on his own fighter, but loses it when Fluff and Marie convince Donati to fight for real. Thinking he’s been double-crossed, and generally a sore loser, he figures revenge is a dish best served really, really hot. So he finagles his way backstage, holds Donati, Fluff and the Kid hostage, and then he and Donati shoot each other. Donati gets some final words to Fluff before dying, then she slumps off into the night. The world is left to the boring kids.

Neither of those up-and-comers, by the way, lasted as long as the old hands. Robinson kept going into the 1970s, Davis into the late ’80s, while Jane Bryan, highly touted and a favorite of Davis’, made 17 movies between 1936 and 1940, then quit to marry Justin Dart, a bigwig in the pharmaceutical industry, a staunch Republican, and a friend and adviser to Ronald Reagan. She spent the rest of her life doing GOP things. Wayne Morris kept acting but died young, at age 45, in 1959, of a heart attack. His best-known role may be as a cowardly soldier in Stanley Kubrick’s “Paths of Glory,” which is ironic: as a pilot during World War II, he shot down seven Japanese planes, helped sink five Japanese ships, and was awarded four Distinguished Flying Crosses and two Air Medals.

Silent film star Harry Carey has a small role as a fight trainer, and he’s good: calm, wise. Among Bogie’s gang, I particularly like Ben Welden, whose Buzz Barett is perpetually smiling in the most annoying fashion. Spain’s Soledad Jimenez plays the Italian mother of the Jewish-Romanian fight manager. Early ads for the film include Pat O’Brien in the cast, but I can’t figure out what his part would be, since both Robinson and Bogart are mentioned as well. Not Galahad, surely.

Overall, there’s not much here but history. And a lesson: Find someone who looks at you the way every woman in this movie looks at Wayne Morris.

“Someone wanted me?” “I bet plenty of ’em do, honey.”

Monday August 09, 2021

Movie Review: The Little Giant (1933)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It’s basically a one-joke movie, isn’t it? An Al Capone-type Chicago gangster, J. Francis “Bugs” Ahearn (Edward G. Robinson), sees the writing on the wall when FDR is elected and Prohibition is about to end, and decides to go legit. So with his ill-gotten gains ($1.25 million), and his right-hand man, Al (Russell Hopton), he moves to Santa Barbara and tries to enter high society. “I’m gonna mingle with the upper classes,” he says. “I’m gonna be a gentleman!”

The joke is he thinks the upper classes have class but they don’t. In fact, the very rich are bigger crooks than he is, and take him for a yap, a chump, a sucker. This goes on for 60 minutes of a 75-minute movie. It’s only at the end that he wises up, gets the gang back together, and makes the rich and corrupt pay. That’s the fun part.

The joke is he thinks the upper classes have class but they don’t. In fact, the very rich are bigger crooks than he is, and take him for a yap, a chump, a sucker. This goes on for 60 minutes of a 75-minute movie. It’s only at the end that he wises up, gets the gang back together, and makes the rich and corrupt pay. That’s the fun part.

Man, if only he were around today. Send him over to Mar-a-Lago.

Anyway, the one joke isn’t good enough. Much of the movie is a slog. It’s just an hour-plus, but it took me several sittings to get through. “Bugs” makes typical working-class errors: says “Pluto” for “Plato,” assumes a “Siamese beauty” has a twin. Robinson’s good—he’s always good—but most of the lines (from the otherwise reliable Robert Lord-Wilson Mizer team) don’t stick. The dame he falls for, Polly Cass (Helen Vinson), is a leech, and so is her entire family. They’re only interested in him when they find out he’s got money; then they’re scared when they find out he’s that Ahearn—Ahearn is the wrong name for a gangster anyway—but still, for a time, they get the better of him. And sorry to be crass, but for Bugs to fall so hard for so long, the actress playing Polly should’ve been a stunner. Vinson’s fine but not a stunner.

Mary Astor plays Ruth, the stolid working woman who rents him his mansion. Turns out, it used to be her family’s until the Casses bilked her father for his fortune—sending him to an early death. That shift in focus is disappointing as well. Initially, all of high society seem suspect; by the end, it’s just the Casses. Ruth sees them as aberrations rather than as representative. The rich get off the hook again.

I do like an early “Public Enemy” reference, as Al and Bugs reminisce about the old days:

Al: Remember all the good times we had together? Remember the time we busted into that loft after them furs?

Bugs: Yeah, and you went into a panic over that big stuffed polar bear in the corner.

Al: I give it to him, didn’t I?

Bugs: Yeah, you sure opened up on him. The cops on the west side was swarming around that joint like they was bees around a hive!

It’s almost like the Warners Studio reminiscing about the glorious pre-code era as it was coming to an end.

Thursday August 05, 2021

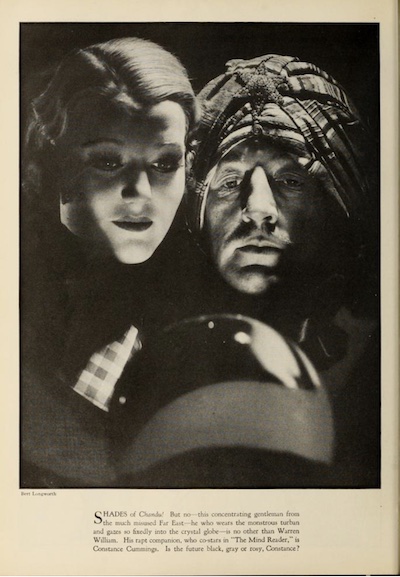

Movie Review: The Mind Reader (1933)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The titular mind reader, Chandler, AKA Chandra the Great (Warren William), gives a speech near the end of the film that reminded me of a speech Jimmy Cagney gives as a PR rep in “Hard to Handle,” which was released by the same studio, Warner Bros., in the same year, 1933.

Cagney’s speech, near the beginning of his film, is peppier and more modern:

Sure, yaps, suckers, chumps, anything you want to call them—the public. And how do you get ’em? Publicity. Listen, Mac, here’s the idea: You take the bankroll, open a publicity agency. Exploitation, advertising, ballyhoo, bull, hot air—the greatest force in modern-day civilization. ... I’m telling you, Mac, the public is like a cow bellowing, bellowing to be milked.

that isn't really in the movie.

“Tell the chumps what they wanna hear.”

Chandra’s speech is spoken directly to those yaps, suckers and chumps. He’s on stage, drunk, and tired of the scam:

You ask me to tell you things. You think I know! I’ll tell you what I know. I’m the guy who knows how stupid you are. You pay me money to wreck you, torture you, boil you up, play to you, and laugh at you. Sitting there like a school of fish with your mouths open!

It’s the movies letting us know how the world works—and what the people who pull the levers really think of us. There's even a kind of smuggled-in admission that the lever-pullers include Hollywood. Look at that “wreck you, torture you” line. Chandra doesn’t really do that in his act. That’s what the movies do in theirs. We pay them money to sit in the dark and be wrecked, roiled, played with.

So guess when Warners released “The Mind Reader”? April 1st. A bit on the nose.

The most interesting man in the world

What else do these two movies have in common? Screenwriters Robert Lord and Wilson Mizner. For the moment, let’s focus on Mizner.

Apparently he was one of the all-time great raconteurs and con men. The son of a diplomat, he was a 6’ 5” cardsharp, hotel man, dealer in fake art, prizefight manager, and roulette-wheel fixer. In the 1890s, he and his brother Addison joined the Klondike Gold Rush in Canada but to bilk the miners rather than pan for gold. (Bilking is where the real gold is anyway; it never runs out.) Afterwards, he became a playwright, opium addict, founder and co-owner of the world-famous Brown Derby restaurant in Los Angeles, and a wit who coined some of our great cynical phrases:

- “Be nice to people on the way up because you'll meet the same people on the way down.”

- “When you steal from one author, it's plagiarism; when you steal from many, it's research.”

- “Never give a sucker an even break.”

Apparently he was both friends with Wyatt Earp and the model for Clark Gable’s restauranteur/gangster in the 1936 smash hit “San Francisco.” Remember Hyman Roth’s speech in “The Godfather Part II” about the kid who had a dream of building a city in the desert as a stopover for GIs? “That kid’s name was Moe Greene, and the city he invented was Las Vegas.” You could say the same about Wilson’s brother Addison and Boca Raton, Florida, which Wilson helped him create, and from which both men fled after their corrupt wheeling and dealing became known. Stephen Sondheim was so entranced by their story he wrote a musical based on them: Road Show. It was a helluva life.

Some of that life seems to be in “The Mind Reader.” The movie opens with Chandler, and his two right-hand men, Frank (Allen Jenkins) and Sam (Clarence Muse), making their itinerant way through the U.S. as they try to perfect their scam. Chandler plays a “Painless dentist” in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and a “Wonder Hair Tonic” salesman to Black folks in Nashville, Tennessee. In Emporia, Kansas, he talks up Frank as a champion flagpole sitter (50+ days, etc.) but the only ones stopping by are two kids who whisper their question. Chandler listens and repeats, “How does he what?” Which, yes, is our question, too.

It’s in Emporia where they see a grift that works:

SWAMI RAJA

The Marvel of the Age

HE TELLS PAST PRESENT AND FUTURE

Frank does some research, discovers that people spend about $125 million a year on fortune-telling, and the other shoe drops for Chandler. “It’s a sure cleanup!” he says. “All you gotta do is look wise, tie a bath towel around your head, and tell the chumps what they wanna hear. The whole world is full of hopeful suckers. Just keep promising them things.”

Their grift isn’t bad. Sam collects questions from the audience, seems to burn them on stage, but secretly funnels them to Frank below, who reads them via electronic hookup to Chandra. Then they set up private sessions for $1 a pop.

Their grift isn’t bad. Sam collects questions from the audience, seems to burn them on stage, but secretly funnels them to Frank below, who reads them via electronic hookup to Chandra. Then they set up private sessions for $1 a pop.

To be honest, the movie doesn’t do nearly enough with the grift. It momentarily wrecks it for a one-note gag—when Chandra tells a dude he won’t have any children but his wife will have three, which isn't exactly what the chump wants to hear—then permanently wrecks it by having Chandra fall for Sylvia (Constance Cummings) in Kokomo, Indiana. She’s an innocent kid, but he woos her anyway and brings her along. So now we have three scam artists and an innocent. What happens when she finds out?

Initially, not much. In fact, she joins the scam, reading the notes to Chandra while Frank is busy breaking into a jewelry story—a crime Chandra will “predict” to those present. In the act, Frank can’t help himself and also lifts a diamond, which Chandra then uses for Sylvia’s wedding ring.

If he had corrupted her, the movie might’ve stayed interesting. Sadly, the opposite. A woman (Mayo Methot, Bogart’s wife before Bacall) shows up at their hotel, says Chandra gave her advice that led her to give up the man she loved, who subsequently committed suicide, and what's what she does immediately after leaving the room: down an elevator shaft. That’s enough for Sylvia. She's about to leave town when Chandler shows up at the train station on bended knee promising to reform.

Cut to: Chandler in New York City, trying to sell brushes door to door in the snow.

Not a bad gag. A tame Chandler, though, is a dull Chandler. Thankfully, he runs into Frank again, who’s now a chauffer:

Frank: A guy with your con, your larceny, selling brushes? What’s the idea?

Chandler: I’m on the straight and narrow. You know. The wife.

Frank: The wife. Love. Marriage. Honesty. Now there’s a combination guaranteed to get anybody in the poorhouse.

Which leads to the second successful grift. Same deal, but now he’s Dr. Munro, and he gets the inside dope from chauffers like Frank, who know about the peccadillos of the powerful men they drive around. It’s actually a more honest grift. Instead of making up lies about the future, Chandler is telling the truth about the present—and the wives are buying it.

But same deal again. One husband who’s been fingered shows up, tries to get tough, there’s a gun, it goes off, he dies. Chandler scrams to Juarez, New Mexico, where he’s now “The Great Divoni,” while Sylvia, who was also at the scene of the crime, is railroaded by the cops into taking the murder charge. That leads to Chandler’s drunken rant. And that leads to his 11th-hour return to New York and confession at the DA’s office. Then under police guard he visits her hospital room—she collapsed at her murder trial—tells her he wants her to divorce him, but no, she’s sticking by him. Out in the hall, he runs into Frank and Sam. As the cops pull him away, Frank gets in the last line: “Sure is tough to be going away just when beer is coming back.”

More on Muse

A few words on Clarence Muse, who played Sam, and who was one of the few Black actors during this time that didn’t contort himself into the stereotypes of the day. Here, again, he’s his own man. A running gag is Sam and Frank arguing about horse racing, with Sam usually getting the best of him. More startling is when Sylvia shows up backstage at the carny and Sam checks her out—tilting his head to the side as she enters Chandra’s trailer. “That’s a nice-looking girl,” he says afterwards. Pre-code or no, I’m shocked this got through censors. At the least, I assume it was relegated to the cutting-room floor by a lot of local censors in the South and Midwest. Shame we don’t see more of Muse in the movie. Not to mention the movies.

Vivian Crosby gets a story credit, while Lord and Mizner share screenplay credit, as they do on “Hard to Handle,” “Frisco Jenny” and “20,000 Years in Sing Sing.” According to Philippe Garnier’s book Scoundrels & Spitballers: Writers and Hollywood in the 1930s, Lord did all the typing and most of the writing, though Mizner “could be counted upon to inject some authenticity or wit in whatever prison or gangster yarn the studio was churning out.” Mizner lived only two days past the film’s premiere, dying of a heart attack at the Ambassador Hotel on April 3, 1933, age 56. His final last words, most likely apocryphal: “I’m dying above my means.”

This one was directed by frequent Cagney collaborator Roy Del Ruth, with cinematography from Sol Polito, and we get some nice shots in the early going. I also like the map interludes. Probably played well in those places, too. It gave the people what they wanted—themselves.

Overall, “The Mind Reader” is worth watching and comes close to being quite good. But I gotta go with Frank: love, marriage, honesty? Now that’s a combo guaranteed to ruin a nice larcenous picture.

Friday June 18, 2021

Movie Review: A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I’d always assumed James Cagney wanted to be in the 1935 Warner Bros. production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” as a chance to to do something different than the usual gangster, grifter, or hot-shot pilot roles he played. But according to biographer John McCabe, and Cagney’s own memoir (as told to McCabe), he had no real desire to play Shakespeare. “It was not, he said, his cup of tea,” McCabe wrote.

So then I wondered if Warners cast him as Bottom, the fool who becomes a literal ass, as punishment for forever fighting them over pay. You act like a stubborn mule, we’ll cast you as a stubborn mule. Nope again. Jack Warner wasn’t really involved in the casting, while Hal Wallis wanted character actor Guy Kibbee for the part.

So how did it happen?

Max Reinhardt. He directed a lavish version of the play on Broadway, took it on the road, and when Wallis saw it at the Hollywood Bowl he was inspired enough to suggest making it a film. (He was also inspired enough to put the girl playing Hermia under contract: Olivia de Havilland. One out of two ain’t bad.) And it was Reinhardt who insisted on casting Cagney. “Few artists have ever had his intensity, his dramatic drive,” he said. “Every movement of his body, and his incredible hands, contribute to the story he is trying to tell.”

Max Reinhardt. He directed a lavish version of the play on Broadway, took it on the road, and when Wallis saw it at the Hollywood Bowl he was inspired enough to suggest making it a film. (He was also inspired enough to put the girl playing Hermia under contract: Olivia de Havilland. One out of two ain’t bad.) And it was Reinhardt who insisted on casting Cagney. “Few artists have ever had his intensity, his dramatic drive,” he said. “Every movement of his body, and his incredible hands, contribute to the story he is trying to tell.”

Shame it didn’t work out—for either of them.

Most lamentable

Reinhardt was primarily a stage director. His film work was minimal and dated: just three short photoplays in Germany in the early days of the silents. From Cagney’s memoir:

Because Reinhardt was essentially a spectacle director … he remained largely on the sideline while Bill Dieterle directed. Reinhardt, so used to broad stage gestures, made some of the actors do things that were, I thought, ridiculous for the screen. We used to stand back, watching him, and say, “Somebody ought to tell him.”

I'm curious if Reinhardt directed Cagney in this manner because he brings way too much energy to the role. He’s breathless from the beginning and it gets worse. And when he imitates the storm? Talk about broad stage gestures. Somebody ought to have told him.

Bottom’s personality here, the braggart, isn’t that different from some of Cagney’s successful roles— “Blonde Crazy” and “Devil Dogs in the Air” to name two—so it's a little odd that it doesn’t work. The theater troupe Bottom is part of, which is led by Peter Quince (Frank McHugh), is set to perform “The Most Lamentable Comedy and Most Cruel Death of Pyramus and Thisbe” during wedding-day celebrations for Duke Theseus and Queen Hippolyta, but they’re all hopeless. That’s the gag. Bottom is the big fish in the little pond, and he gets cast as one of the leads, Pyramus, but he wants to play him as tyrant rather than lover. Then he wants to play the other lead, too. Then he wants the lion’s part. When Quince tries to placate him by saying he’d be too fierce a lion, he suggests a dovelike lion.

It’s tiresome. When is Cagney ever tiresome? Here. I guess it’s partly the broad gestures and breathlessness, but it feels like there’s something else. The glint in his eye is missing. He’s stupefied and selfish rather than joyous and looking for an angle.

You know the overall story. Different groups converge in the woods on a summer night, where they’re toyed with by spirits and faeries:

- Hermia and Lysander (de Havilland and Dick Powell) are leaving to get married against her father's wishes

- They are pursued by Demetrius (Ross Alexander), who loves Hermia, and Helena (Jean Muir), who loves Demetrius

- Bottom’s theater troupe meets to practice the play

(The theater kids never interact with the young lovers, do they? Just with the faeries. Maybe that’s another problem: Quince’s troupe is not relevant to the main storyline.)

Meanwhile, the king of the faeries, Oberon (Victor Jory), is angry with his queen, Titania (Anita Louise, quite lovely), who has become enamored of an Indian changeling, and he wants to punish her for it. So he instructs his magic sprite, Puck (Mickey Rooney), to rub a love-in-idleness flower on her eyelids when she’s asleep, so that when she wakes she’ll fall in love with the first thing she sees. (He’s hoping for an animal.) Oberon then hears Demetrius lambasting Helena, and he instructs Puck to do the same to such a cruel man. It’s this latter order that creates chaos: Puck thinks Lysander is Demetrius and causes Lysander to fall madly in love with Helena. A correction with Demetrius means both men are now pursuing Helena rather than Hermia, and Helena thinks they’re making fun of her, while Hermia accuses Helena of stealing her man. Arguments, fights, ensue.

On his own, Puck transforms Bottom’s head into that of an ass, causing the rest of the troupe to flee in terror. Initially unaware of the change, Bottom sits waiting for them to return. He sings to himself, which awakens Titania, dabbed with the magical flower, and she falls for him.

For all the Shakespearean misunderstandings, most everything happens the way Oberon wants: He gets the Indian changeling, gets Titania back, and orders Puck to fix everything else. Puck does. Kinda. Yes, Bottom is restored, as is Lysander, but Demetrius remains in love with Helena. I guess we assume that’s for the good—it allows all four young people to be happy—but it doesn’t say much for his free will. Imagine if the spell was removed when Demetrius was 60. Poor guy.

Afterwards, there's the wedding celebration, at which the Quince troupe performs lamentably to the condescending amusement of the royals and rich folks.

More cynical than Gore Vidal

A few things work. The flying of the faeries is pretty amazing, and makes me wonder what might’ve happened if a major studio had attempted a superhero film in, say, the 1940s. (Superheroes not having been invented at this time.) Most of the Warners players aren’t bad, given their non-Shakespearean backgrounds, while Joe E. Brown is hilarious as Flute, one of Quince’s troupe. We even get a mid-’30s Warners vibe at times. Early on, for example, Demetrius finks on our couple to Hermia’s father (Grant Mitchell), who drags her away, leaving Demetrius and Lysander staring at each other. Lysander, with the upper hand, then does a kind of insouciant tie-loosening gesture and leaves singing to himself.

Mickey Rooney, who also played Puck on the stage, got some of the best notices, but it’s another performance that feels too broad, too loud. Even so, it had quite the effect on Gore Vidal, age 10, who was mesmerized by Rooney and sought out the play and the author. Because of this film, he claims to have read all of Shakespeare by the time he was 16. “Yes, Cymbeline, too,” he writes in Screening History, before adding, “I’m sure my response was not unique.” It’s one of those rare moments when I feel more cynical than Vidal.

Warners’ gamble didn’t do great box office but it was nominated for four Academy Awards, including best picture, and won two: cinematography for Hal Mohr (the only write-in nominee to win) and editing for Ralph Dawson. Trivia question: Name the four Cagney movies nominated best picture. This one, of course, but the other three?

Interesting the fates for these stars. Both Cagney and de Havilland broke free of oppressive Warner Bros. contracts (Cagney in '36, de Havilland in '44), helping upend the studio system. Dick Powell, singing sensation of the '30s, became a hard-boiled detective in the '40s. The rest of the lovers quadrangle were less lucky. Alexander, who played Demetrius, was a closeted homosexual who killed himself in 1937, age 29, while Jean Muir was named (along with Cagney and Bogart) by John L. Leech as a communist before the Dies Committee in 1940. She was cleared, left Hollywood in the '40s, but was named again in the 1950s and lost her livelihood in radio and TV. Her last screen credit is “Naked City” in 1962. She died in 1996.

As to the best picture trivia? Yes to “Yankee Doodle Dandy.“ No to any of the gangster flicks: “Angels with Dirty Faces,” “The Public Enemy,” ”The Roaring Twenties“ and “White Heat.” Nor to ”Love Me or Leave Me," which garnered Cagney his final Oscar nod. But yes to another movie from that year: “Mister Roberts.” I'll tell you the final one, because unless you know it you won't guess it: “Here Comes the Navy” from 1934. None won.

Bottom and Titania, both punished.

Saturday June 12, 2021

Movie Review: Employees' Entrance (1933)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I’ve seen a lot of pre-code movies, so I know the score, but “Employees’ Entrance” still shocked me.

Warren William plays Kurt Anderson, general manager of Franklin Monroe & Co. department store, who is also the worst aspects of capitalism personified. “My code is smash—or be smashed,” he says. When a clothier, Garfinkle (Frank Reicher), can’t deliver all of an order for an advertised sale, Anderson cancels the order and sues the man for the advertising and estimated loss on the sale—ruining him in the process. When his right-hand man, Higgins (Charles Sellon), offers no new ideas to boost sales, Anderson not only fires him but insults him out the door—calling him old, sick, dead wood. Later, Higgins commits suicide, and while everyone stands around distraught, Anderson offers this eulogy: “When a man outlives his usefulness, he ought to jump out a window!”

Yet somehow this horror show comes off as the hero of the story. Maybe because he’s true to his code? He tells off subordinates and superiors equally. He sneers at softness and praises and promotes ruthlessness. When Denton Ross (Albert Gran), a jolly executive, admires Anderson’s tenacity, Anderson responds, “Beginning to like me, eh? I despise you for that.” When his new right-hand man, Martin (Wallace Ford), storms into Anderson’s office with a bottle of poison, threatening to kill him, Anderson offers the man a gun: “Go ahead—and don’t miss.” When Martin hesitates, Anderson calls him yellow. When Martin merely wings him, Anderson says dismissively, “You can’t even shoot straight, can you?”

Yet somehow this horror show comes off as the hero of the story. Maybe because he’s true to his code? He tells off subordinates and superiors equally. He sneers at softness and praises and promotes ruthlessness. When Denton Ross (Albert Gran), a jolly executive, admires Anderson’s tenacity, Anderson responds, “Beginning to like me, eh? I despise you for that.” When his new right-hand man, Martin (Wallace Ford), storms into Anderson’s office with a bottle of poison, threatening to kill him, Anderson offers the man a gun: “Go ahead—and don’t miss.” When Martin hesitates, Anderson calls him yellow. When Martin merely wings him, Anderson says dismissively, “You can’t even shoot straight, can you?”

All of which is kind of fun. But then there are the rape scenes.

In their place

“Employees’ Entrance” is ostensibly a Depression-era romance between the up-and-coming Martin and the bewitchingly beautiful Madeline (Loretta Young), who models clothes for customers at the store. But every romance needs its complication, and the complication here is Anderson, their boss.

Martin is an up-and-comer because he has good ideas—putting the men’s briefs near the women’s dept., for example, since wives tend to buy for their husbands—and also because he’s ruthless. Anderson overhears him refusing to pay an artist for subpar work, then dismissing him with contempt, and he’s so impressed he offers him Higgins’ job. Then he peers in close.

Anderson: You’re not married are you? … This is no job for a married man. Where would I be with a wife hanging around my neck?

Martin: Don’t you like women?

Anderson: Sure, I like them. In their place! But there’s no time for wives in this job. Love ’em and leave ’em—get me?

Martin gets him. Except he’s just begun a romance with Madeline; and when they marry, they have to keep it secret from the boss. That’s the complication—or part of it. The bigger part is that earlier in the movie Anderson rapes Madeline.

That’s how we’d view it today anyway. Did Warner Bros. in 1933? Or society at large? Nah. A cursory search of the movie’s 1933 reviews indicates a “both sides” kind of thing: what girls do for a $10-a-week job; how employers take advantage. It's how the movie was marketed: titillation with a wink.

Here’s how it goes down. We open on a pullback shot of a busy department store over which we get its annual sales figures—$20 million in 1920—and then a 10-second vignette of a longtime employee getting fired by the unseen Mr. Anderson. Through the 1920s we go, with the ruthless Anderson raising annual sales to $100 mil by 1929. After the Wall Street Crash, sales dip to $45, and the board meets with concerns of Anderson’s overzealousness, suggesting he get a handler, but Anderson will have none of it. He demands twice the salary and no supervision or he’ll go to their competition. Then he insults all of them, particularly the fatuous owner Mr. Monroe (Hale Hamilton).

William is great in the role. With his angular face, sloe eyes, prominent, dignified nose and moustache, he already has a wolfish aspect, and he makes the most of it. One night, patrolling the store after hours, he hears a piano playing in a “model home” and investigates. It’s Madeline. The conceit is she’s homeless and hungry and needs a job, but at the same time she’s as put-together as a young Loretta Young. And if she's hiding there, why the piano playing? Kind of a giveaway. Anyway, sensing all this, the wolf closes in. He agrees to feed her; he agrees to give her a job. Then when she tries to leave, he closes the door and looms close.

Anderson: You don't have to go, you know.

Madeline: Oh, yes I do.

Anderson: No, you don't.

At which point he kisses her. Kisses? More like mashes his lips against her unresponsive ones. Fade out.

That’s the first instance. The second, which occurs at the annual office party, is even worse. By this time, Martin and Madeline are married and fighting. Off Martin goes to drink and sing “Sweet Adeline” with the boys, while Madeline sits and frets by herself. And the wolf closes in. Anderson plies her with champagne, and when she gets woozy he tells her to go to his room, 1032, to lie down for a bit. He’ll remain at the party, he says. For some reason, she believes him. Five minutes after she goes up, he goes up, finds her asleep on the bed, positioned alluringly, and loosens his tie. Fade out.

We expect some kind of comeuppance for all this—isn’t that how movies work?—but that's the shocking part of “Employees' Entrance”: It ever arrives. I don’t even think it departs. When Anderson finds out about the marriage—when he discovers that the woman he’s twice assaulted is married to the right-hand man he considers almost a son—he gets mad at them. “She’s hogtied you, my boy,” he tells Martin. “Turn her loose. A little money’ll do the trick.” The most startling moment is when Anderson blames Madeline for his own sexual assaults when he knows Martin is eavesdropping on the conversation:

“I was all right for you the first night I met you. I was all right for you the night of the party. Let’s see, you were married to Martin then, weren’t you? And that’s what you call love. You women make me sick! Come on, come on, how much?“

Holy shit.

That’s when she slaps him, leaves, drinks poison, is rushed to the hospital. Cue gun scene with Martin.

OK, there’s nearly comeuppance. For some reason, the board is ready to drop him again, but Ross, who is supposed to be Anderson’s handler, now works to get the proxy votes from the globetrotting Monroe to save Anderson. And he does. And at the last minute, they rush to the meeting to save the day. It’s a common movie trope—we’ve seen it a million times—but it’s usually about saving the hero. Here, it’s about saving a ruthless SOB who uses his position to sexually assault women … who, sure, also seems like he's the movie’s hero.

It almost ends there, too, on our victorious hero, back to his ruthless ways. But then we get a final perfunctory scene of the cuckolded Martin visiting the sickly Madeline at the hospital and promising they’ll start over. “It’s been done before,” he says helplessly.

Fade out.

Boop-oop-a-doop

Overall, the film is light comedy, with blackout-like “bits” sprinkled throughout. A Jewish man considers a football for his son until the salesman calls it a “pigskin.” A woman asks where the basement is and a bored saleslady tells her “12th floor.” There are perennial problems with the men’s room, the elevator operator keeps enumerating (in a flat voice) the long list of items available per floor, and the company proudly—and one assumes speciously—reiterates that its founders are descendants of Benjamin Franklin and James Monroe.

“Employees’ Entrance” was directed by Roy Del Ruth—who did some of the better pre-code Cagney flicks: “Blonde Crazy,” “Taxi!” and “Lady Killer”—and heralded the return of Alice White, a late-era silent star who got involved in an early 1930s scandal. Apparently she had an affair with British actor John Warbuton and accused him of beating her so badly she required plastic surgery; allegedly, she and her ex, writer-producer Sy Bartlett, then hired goons to beat up Warburton. All of that hurt her career. For a while, she did comic supporting roles, such as this and “Picture Snatcher,” married actor-writer John Roberts in 1940, then disappeared from the screen. In the 1950s, after a divorce, she went back to secretarial work, which she’d been doing when Charlie Chaplin discovered her in the 1920s. She died in 1983.

Here she plays Polly Dale, another clothes model. She’s great: funny, sassy, brassy. Anderson hires her to seduce the portly Ross, and we see her using her boop-oop-a-doop charms on him but to not much avail. She reports back he only wants to play chess. “Try Post Office,” Anderson tells her.

Big department stores were new things back then, and the trailer for this one promised to tell you the stories behind the scenes, but you don't have to squint much to see the whole thing as a metaphor for a movie studio. Everyone's scrapping to get by in the depths of the Depression, while one man, a near-dictator, a mogul say, ruthlessly cracks the whip and shows them the way—while taking advantage of women on the side. No wonder Warners made Anderson the hero. He’s them.

All in fun in 1933.

Monday June 07, 2021

Movie Review: Ceiling Zero (1936)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Ceiling Zero” is both same-old same-old and not.

It’s the fourth James Cagney-Pat O’Brien picture in two years, their second as pilots, with Cagney once again the hot-dog womanizer who endangers everyone while O’Brien is the firm man in command who teaches him how to be a team player. In “Devil Dogs in the Air” and “The Irish in Us,” Cagney steals O’Brien’s girl; here, he’s already stolen her. He had a relationship with her years before that O’Brien doesn’t know about. For good measure, he also steals aviatrix “Tommy” Thomas (June Travis) away from her fiancé. All of this is familiar.

What’s new is the movie’s pedigree and it informs everything else. The earlier flicks were directed by Lloyd Bacon, a solid journeyman, and this is from Howard Hawks, a famed auteur. But I think the big difference is the screenwriter. Frank Wead was a U.S. Navy pilot and early authority on flying who suffered a freak spinal injury accident in 1926 that left him paralyzed. At that point, along with his sober aviation manuals, he began writing fiction of pilot derring-do for the pulps, some of which were bought by Hollywood. Eventually he began writing directly for the movies: “Air Mail” (1932) and “West Point of the Air” (1935), among them. He became friends with director John Ford, and after Wead’s death in 1947 Ford made “The Wings of Eagles” in 1957, which was based on Wead’s life and writings. John Wayne played Wead.

What’s new is the movie’s pedigree and it informs everything else. The earlier flicks were directed by Lloyd Bacon, a solid journeyman, and this is from Howard Hawks, a famed auteur. But I think the big difference is the screenwriter. Frank Wead was a U.S. Navy pilot and early authority on flying who suffered a freak spinal injury accident in 1926 that left him paralyzed. At that point, along with his sober aviation manuals, he began writing fiction of pilot derring-do for the pulps, some of which were bought by Hollywood. Eventually he began writing directly for the movies: “Air Mail” (1932) and “West Point of the Air” (1935), among them. He became friends with director John Ford, and after Wead’s death in 1947 Ford made “The Wings of Eagles” in 1957, which was based on Wead’s life and writings. John Wayne played Wead.

Wead also wrote one play, “Ceiling Zero,” about pilots delivering airmail in zero-visibility conditions, which debuted on Broadway in 1935 to mixed reviews. He adapted it himself for the screen, but didn’t adapt it much. Most of the action takes place in a single location: the waiting area/hangar at the Newark branch of Federal Airlines. Pilots come and go, radio operators try to reach them in hazardous conditions, planes crash. The action, and thus the drama, is concentrated, and feels like a filmed play.

Actually, you know what it reminded me of? Those theatrical showcases in the early days of television: Studio One, Good Year Playhouse, Playhouse 90. There’s a close, emotionally heavy, mano a mano sense to scenes. It’s a melodrama, truncated in time and space, and with a low budget. Even the DVD I watched, the French version called “Brumes” (no U.S. version is available for legal reasons), reminded me of kinescopes of early television.

I wish I could—

We don’t see Cagney’s character, Dizzy Davis, until 17 minutes in. I like that. I like it when movies keep the lead offstage but talk him up. With Dizzy, men tend to smile and women tend to frown. Management isn’t too happy, either, when they find out he's been rehired. An early bit of dialogue between Jake (O’Brien) and aviation boss Al Stone (Barton MacLane) is pretty much the movie in a nutshell:

Al: I’m telling you, Jake, Dizzy’s a menace and a liability.

Jake: And the best cockeyed pilot on this airline or any other.

The boss wants college men who are technically expert but we’ve already seen potential problems with them. Eddie Payson (Carlyle Moore, Jr.) is a pilot who checks all the boxes except one: reactions to emergencies. The night before, in the fog, his radio out, Payson panicked and abandoned his plane, and there went $40,000. Surprised Jake doesn’t use this bottom-line argument with Al. Also, what happened to the plane? He was over Pennsylvania. Where did it crash? Did it hurt anyone? Did no one sue anyone during this period? Anyway he gets canned.

Dizzy’s the opposite. He arrives singing “I can’t give you anything but love, baby,” lands crazily, gets tossed around by his pals, Tex and Doc (Stuart Erwin and Edward Gargan), and lands at the feet of Joe Allen, commerce inspector (Craig Allen). Everyone’s got an eye on Dizzy but he maintains his rascally ways. He immediately makes a play for Tommy, strikes out, then bets the others he can get her to come with all of them to Mama Gini’s—their version of the Happy Bottom Riding Club from “The Right Stuff.” He wins.

Hollywood movies are forever tossing together older actors and young starlets without comment but here they comment. Fifteen years separate Cagney and Travis (37 and 22), and ditto Dizzy and Tommy (34 and 19), and he tries to convince her it’s no barrier. Why when she’s 34, he’ll only be 49. They keep upping the ages, flirting all the while, until this:

She: Do you realize when I’m 49 you’ll be 64?

He: When you’re 49 you’ll be rolling around in a wheelchair. I’ll be out dancing.

She: Oh yeah? With who?

He: How do I know—she hasn’t been born yet.

How the times have change. What would be a feminist punchline on SNL today is a winner here. Both chuckle and Tommy seems to soften. They’re about to kiss when Jake butts in.

For all that, the screenplay isn’t too backward-looking. The women are tough, with male names—Tommy, Lou—while Tommy, the beginner, is as enamored of aviation history as she is of Dizzy. After she ditches him at Mama Gini's, he confronts her the next morning, and they all but reverse gender roles. He feigns the vapors at the humiliation of it all; and when he corrects her when she says he's 35, she tells him not to be too sensitive about his age. She’s also up front about her sexuality. She admits she’s attracted to him but “I finally got a hold of myself and said, ‘Tommy, this is alright, but how does he look in the morning?’”

Still, he doesn't give up. He offers her flying lessons on the condition she’ll have dinner with him. His Cleveland mail run? Oh, he’ll get Tex to take it. And does—by feigning a bum ticker in the locker room. Think of it: He hasn’t even done one mail run for the outfit and he’s already shirking his duties.

That moment, 40 minutes into a 90-minute movie, sets up the rest.

The movie opens with a description of the term ceiling zero: “... that time when fog, rain or snow completely fills the flying air between sky or ceiling and the earth.” According to Wiki, the service ceiling is the maximum usable altitude of an aircraft, so ceiling zero is when nothing should be in the air. That’s what Tex winds up flying in. Jake observes that even the seagulls are staying on the ground. So the men, behind radio operator Buzz (James Bush), try to talk Tex home.

Not sure when the movie is set—the opening titles indicate it’s a time when airmail pilots “challenged and conquered ceiling zero” but no date is given. I’m assuming the 1920s or early ’30s? Before radar anyway. Tex not only winds up flying in adverse conditions but he loses radio contact. The men on the ground can hear him but he can’t hear them. Earlier, Tex was the cool, calm counterpart to Eddie Payson’s panic, so when panic begins to creep into his voice, it’s startling, and sets up his end: his plane bursts into flame as he cuts through wires trying to land. All because Dizzy shirked his duties.

The rest is Dizzy’s attempt to make good. Dizzy gets Lawson (Henry Wadsworth), Tommy’s fiancé, and the pilot working on the new de-icing protocol, to tell him all about it; then he decks him and takes his place. It’s again ceiling zero weather and he radios back the dope on the de-icers: “Pressure has got to be doubled. And the rear tube has to be moved back at least eight inches, so the ice won’t fall behind it.” Eventually the wings ice up too much and the plane plummets. These are Dizzy’s last words:

Give my love to everybody and pay Mama Gini the four bucks I owe her. So long, baby, don’t be mad at me. I wish I could—

I wish I could. Not bad last words. The last thoughts for most of us, I imagine.

Dizzy and Tex redux