Culture posts

Monday December 23, 2013

Saddest T-Shirt Ever

This was for sale at a T-shirt shop at the Mall of America in Bloomington, Minn. What kind of idiot would buy this? Wear this? How puny do you have to feel to want to brag about this—something that most likely had nothing to do with you and ignores not only the other countries involved but history. Since when do wars that led to the death of tens of millions of people become something like Super Bowl championships?

Ninety percent of the shop was this way: sad and stupid. I complained as we stood outside waiting for a friend to finish shopping, and Patricia and I had the following conversation:

Patricia: I don't know. T-shirt shops have always been bad.

Me: They weren't this loutish back then.

Patricia: America wasn't this loutish back then.

Saturday September 21, 2013

How the Miss America Controversy is like the Movie 'Crash,' and Other Observations

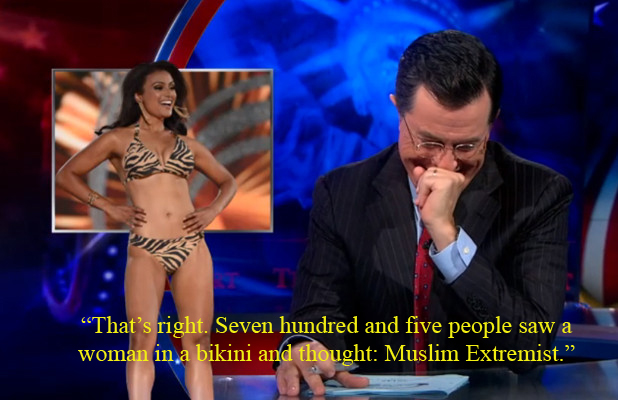

My friend Tim alerted me to this quote from Aasif Mandvi on “The Daily Show” the other night, reacting to the Miss America/Twitter controversy:

Look, John, it's Twitter. It's like that movie “Crash”: You've got 140 characters and 120 are racist for no apparent reason.

You know about the controversy, right? Nina Davuluri, an American of Indian descent, as in India the country, as in Gandhi and “Slumdog Millionaire,” won the Miss America crown over the weekend and a few racist people on Twitter had a shit fit. They called her Miss 7-11, Miss al-Qaeda. They said, “She's a TERRORIST,” and “This is AMERICA!” It's just stupid shit. The world is full of stupid people and now they're online. The Pakleds have spoken.

The early reaction on social media and Salon was one of umbrage, which is a little boring. A better reaction came from “The Daily Show” and “Stephen Colbert.”

That's brilliant. Or: that's truly how sad and stupid those people are. So sad and stupid they probably don't even get the joke.

Then we got Aasif, my brother of the double-a from another continent, with his critique via “Crash,” which longtime readers know I didn't exactly think was best picture material. Brilliant again.

BTW: In the various footage about the controversy (or kerfuffle, or blip), we'd often get shots of Ms. Davuluri in the talent competition doing a Bollywood-type dance. I kept thinking, “It looks like she's doing that 'Dhoom Tana' dance from 'Om Shanti Om,” which is one of about three Bollywood movies I know. Turns out? She is.

In the end? Racists with a foot in the 19th century objected that a competition that had its heyday in the middle of the 20th century was won with something reflecting 21st century values. No surprises here.

Saturday September 14, 2013

What’s Wrong with Jonathan Franzen’s ‘What’s Wrong with the Modern World’?

First there’s the title. It reminds me of “The Secret of Life,” the awful title of the awful article Andrew McCarthy’s awful character finally gets published in the awful “St. Elmo’s Fire.” It’s a title that’s too stupidly general. What’s wrong with the modern world? That’s a wide target, boyo. At the same time you think, “Well, how can Franzen not hit that one?”

He manages not to. A lot of his targets are my targets, too: modern technology, the Internet, “cool,” the pauperization of freelance writers, the marginalization of almost everything I once considered central to the culture. So he should be speaking for me. Yet for most of the essay he doesn’t speak for me.

Franzen is attacking the early 21st century through the writings of Karl Kraus, an Austrian satirist, who attacked the early 20th century. Franzen’s first target? Those Mac vs. PC ads. Seriously. It’s a form and content argument, a “cool” vs. “uncool” argument, and Franzen places himself squarely among the uncool Microsoft/PC people. He backs the content of the PC, its utilitarianism, over the meaningless form of the Mac. He writes:

Simply using a Mac Air, experiencing the elegant design of its hardware and software, is a pleasure in itself, like walking down a street in Paris. Whereas, when you’re working on some clunky, utilitarian PC, the only thing to enjoy is the quality of your work itself. As Kraus says of Germanic life, the PC “sobers” what you’re doing; it allows you to see it unadorned.

Until it crashes.

That's a joke but it's a true joke. Mac is not only better in form but in content; in code. The Mac is both more beautiful and more utilitarian. But then Franzen isn’t really talking about the product but our interaction with the product. He’s apparently saying it’s harder to see ourselves against the beautiful; it’s easier to see ourselves against the plain or ugly. Meaning Franzen should be happy with the way our modern cityscapes have developed. We should be able to see each other well now. Hey, you. I know you.

Franzen keeps taking these cheap shots. His complaints are monumentally small and of the straw-man variety. He criticizes Salman Rushdie for “succumbing” to Twitter, which apparently means being on it. He’s disappointed in those who hold up the Internet as somehow positively “female” and “revolutionary,” when other people’s misinterpretations of the Internet are not the problem with the Internet. He writes:

You’re not allowed to say things like this in America nowadays, no matter how much the billion (or is it 2 billion now?) “individualised” Facebook pages may make you want to say them.

Facebook pages? He’s not even using the right words. He’s attacking our way of seeing a thing even though it’s not how we see the thing.

Here’s another unworthy straw man:

To me the most impressive thing about Kraus as a thinker may be how early and clearly he recognised the divergence of technological progress from moral and spiritual progress. A succeeding century of the former, involving scientific advances that would have seemed miraculous not long ago, has resulted in high-resolution smartphone videos of dudes dropping Mentos into litre bottles of Diet Pepsi and shouting “Whoa!”

Louis C.K. has done a better job, a more human job, parsing this divide.

OK, so Franzen gets better the further he gets into the essay. Here, for example, is something he writes that I can get behind:

... we find ourselves spending most of our waking hours texting and emailing and Tweeting and posting on colour-screen gadgets because Moore’s law said we could. We’re told that, to remain competitive economically, we need to forget about the humanities and teach our children “passion” for digital technology and prepare them to spend their entire lives incessantly re-educating themselves to keep up with it. The logic says that if we want things like Zappos.com or home DVR capability – and who wouldn’t want them? – we need to say goodbye to job stability and hello to a lifetime of anxiety. We need to become as restless as capitalism itself.

That’s getting at it. I like this quote from Kraus:

This velocity doesn’t realize that its achievement is important only in escaping itself.

That’s getting at it even more.

I like the tail-end discussion about the privileged anger of both Kraus and Franzen. Kraus is to Franzen as George W.S. Trow is to me. We all need our previous-generation curmudgeons.

Then Franzen does a back-and-forth thing with Amazon.com, and Jeff Bezos, and the destruction of the thing Franzen holds dear: the physical book, and book culture, and book stores. He delivers the line that’s the most-quoted from this piece: “In my own little corner of the world, which is to say American fiction, Jeff Bezos of Amazon may not be the antichrist, but he surely looks like one of the four horsemen.” He writes this:

Amazon wants a world in which books are either self-published or published by Amazon itself, with readers dependent on Amazon reviews in choosing books, and with authors responsible for their own promotion. The work of yakkers and tweeters and braggers, and of people with the money to pay somebody to churn out hundreds of five-star reviews for them, will flourish in that world.

Except that world is the world, and it’s almost always been the world, and we’ve always been to the side of it. Franzen doesn’t seem to get that. The world of America is a world of selling, of business, of getting ahead. It’s a world of competition. It’s a ruthless world of by any means necessary. If literature is marginalized now it just means it’s more marginalized now. It’s not just marginalized by movies, and radio, and television, as it was in Franzen’s youth, but by everything on the Internet, which is almost everything in the world. It’s almost embarrassing to be here, really, and doing what I’m doing, writing this blog, writing these words, because what’s the point? The other day at a party, a friend said to me, “I’ve been reading your blog lately” and my immediate reaction was one of embarrassment. It was almost as if he’d said, “I saw you standing on the street corner lately, shouting.”

He ends well. Franzen begins horribly and ends well.

Maybe apocalypse is, paradoxically, always individual, always personal. I have a brief tenure on Earth, bracketed by infinities of nothingness, and during the first part of this tenure I form an attachment to a particular set of human values that are shaped inevitably by my social circumstances. If I’d been born in 1159, when the world was steadier, I might well have felt, at 53, that the next generation would share my values and appreciate the same things I appreciated; no apocalypse pending. But I was born in 1959, when TV was something you watched only during prime time, and people wrote letters and put them in the mail, and every magazine and newspaper had a robust books section, and venerable publishers made long-term investments in young writers, and New Criticism reigned in English departments, and the Amazon basin was intact, and antibiotics were used only to treat serious infections, not pumped into healthy cows.

Well shouted, Jonathan. And from a better street corner, too.

Franzen, B.B. (Before Bezos)

Friday August 16, 2013

George W.S. Trow and the Problem of the Final Failed Connection

If you've been reading this blog lately you've noticed a few posts about George W.S. Trow, whose “Within the Context of No Context” I've practically memorized, and whose “My Pilgrim's Progress: Media Studies 1950-1998” I've been reading.

“Pilgrim's” is not as tight as “Context,” maybe because Trow was 20 years older when he wrote it, maybe because William Shawn wasn't around to edit it, maybe because Trow was already beginning to lose his mind. But there are many instances when Trow, as it with a wave of his hand, reveals the world to us. That thing that's been nagging at you for 20 years? This is why. Right here. He connects the disconnected.

Near the end of the book, in the chapter “My Life in Flames,” he gives us one such moment. He writes about the two houses in Hyde Park that are owned and maintained by the federal government: FDR's, of course, and a big marble palace built by Frederick Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius. Trow writes that it was FDR's idea to preserve the Vanderbilt home as a kind of testament to an awful period when too few people had too much of the money:

Near the end of the book, in the chapter “My Life in Flames,” he gives us one such moment. He writes about the two houses in Hyde Park that are owned and maintained by the federal government: FDR's, of course, and a big marble palace built by Frederick Vanderbilt, grandson of Cornelius. Trow writes that it was FDR's idea to preserve the Vanderbilt home as a kind of testament to an awful period when too few people had too much of the money:

At a time—it was wartime—when people had ration coupons; when people had family members who were dying abroad, when soldiers were receiving pay, and I don't know exactly what a G.I.'s pay was during World War II, but was it sometimes fifty dollars a month for a private?—and all of this sitting on top of the Great Depression; in the early 1940s, say, a big marble house built by a robber baron forty years before was—almost an object of terror, one wants to say; a lesson to a mistake that had been made and suffered through.

Trow writes about how in the America of his youth it was not acceptable for some people to be making $15 a week while others lived off the income of their income. Then he writes this:

About three years ago [mid-1990s] I noticed an extraordinary change in the Vanderbilt house ... The guides [rather than being in the spirit of a 1953 public librarian] were all young; not particularly well informed as to the overall flow of American history, but wildly well informed as to the history of the Vanderbilt family; and suddenly out of the woodwork, or out of some books, came all kinds of facts and figures about the Vanderbilts, in terms of how much money they had and how many houses and how many yachts and so forth, which showed that the Vanderbilts, at least in the minds of the guides, and I guess, probably, everyone else, had lately been put on a new kind of Mount Rushmore; these were people who had invented the aesthetic that everyone at this recent moment had decided to embrace. This, of course, represented a kind of defeat for FDR's intent. I didn't see one horrified face or one disapproving face as the young guides described plutocracy in its old form.

Well, Reagan did that, didn't he?

I'm reading and saying, Yes, yes, yes! It's particularly nice that Trow gets to Reagan because he tends to gloss over the Reagan years. The subtitle of the book is “Media Studies 1950-1998” but Trow rarely gets out of the 1950s, his formative years, and only sometimes into the 1960s, when he was at Harvard and then hired by The New Yorker, and also into the 1970s, when “Within the Context of No Context” was written. But here he finally lands on the 1980s: Reagan. The answer.

He adds, “But how on earth did it happen ...” I.e., how did Reagan do it? And he goes into the anti-money aesthetic of the 1960s left-wing, and how he, Trow, was at odds with that aesthetic. He recalls attending a 1969 meeting with a friend about turning Time magazine into a worker-owned publication like Le Monde, and how isolated he felt at that meeting. He liked the culture of the old artistocracy; he palled around with them, as we say today, and yet by 1998 he was against the newly sympathetic relationship to the old plutocracy in a way that his old left-wing friend was not.

He had gone from “Time magazine ought to be like Le Monde” to being at the party for the man who thought that Time-Warner ought to triple in size, perhaps.

Then he repeats his question about Reagan, “Reagan did it, but how did he do it?” and I'm thinking, C'mon. Tell us already! Because I know Trow. It won't be the typical answer. It won't be resentment against blacks (“Welfare queen,” etc.), and it won't be Carter's foreign policy (hostages, etc.), and it won't be Carter's domestic policy (“Are you better off ...” etc.). It won't be the radicalism of the left in the 1960s and the various humiliations America suffered in the 1970s, which is my vague answer. It'll be something better. Something right in front of our eyes.

But he keeps putting it off. He goes into a story about how Richard Avedon took a photograph of Diana Vreeland at the Reagan White House, curtsying before an amused Prince Charles, and how it's a real curtsy, and yadda yadda, and how one of the men in the background of this photo was Jerry Zipkin, whom he derisively calls a “walker,” which is a guy, probably gay, who takes society women around town. Zipkin was in Trow's social circle for a while and Trow didn't think much of him. And then out of the blue, when we're not looking, Trow suddenly gives us the answer:

And I looked at that photograph and I thought, “Oh, God, Studio 54.” And that's how Reagan did it.

Wait—WHAT? Studio 54?

So you read on. Trow writes about how the American aesthetic was often a New York aesthetic, since the center of television and publishing was in New York. Then he tells us a Studio 54 story, his Studio 54 story, how he went there with Diana Vreeland shortly after it opened, and how they sat in the VIP gallery and he looked out at a scrim celebrating cocaine use. Except he had a friend, a good friend, who was suffering from substance abuse at the time so Trow didn't think much of this celebration. Then he writes that Dionysian energy like Elvis' often gets warped by the media filter and how Studio 54 was the 1960s reconfigured as the 1970s; and then he writes this:

As of 1978, New York had run out of specific cultural information; Roosevelt had died and had been buried; Winchell could be Army Archerd from the Hollywood Reporter or any other angry tabloid person; there was no reason Walter Winchell, dancing on Roosevelt's grave, couldn't be that loathesome man who gave us Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous. As to Hyde Park versus the Vanderbilt house, the Vanderbilts had won.

Right. But ... The connection? Between Studio 54 and Reagan?

You can guess, certainly. The VIP gallery stood for exclusivity rather than egalitarianism, as did Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, and suddenly that's what everyone wanted: the exclusivity of the rich and famous. With drugs. There's something to that. But just something. And it doesn't quite lead to Reagan.

For the final few pages of the book, Trow talks up the relationship between FDR and Walter Winchell, the fierce tabloid reporter, and how the Kennedys are the link between FDR and what we have now, “where political figures of every stripe and at every level struggle to find the next camera angle.” But Reagan? It has something to do with George Bernard Shaw's Heartbreak House, apparently, which Trow wants us to read, as well as preindustrial probity, which FDR embodied, and ... And then the book kind of swirls away and leaves you, or me anyway, bereft, without a final connection.

I mean, you go back and dig again. Right, so FDR is aristocratic but egalitarian, and Studio 54 is pedestrian but exclusive. It's undemocratic. FDR came from money but strove for egalitarianism, JFK added glamour, but in the 1960s we dipped our toe in greater egalitarianaism, greater democracy, and came out disgusted. We came out wanting the money and the glamour and the exclusivity. We wanted to be behind the VIP ropes.

But it's not enough. The point of the great thinker and the great writer, which Trow is, is to make the connections the rest of us miss; but Trow has a nasty habit, and this goes back to “Context” as well, of leading us to the Great Connection and then abandoning us there while he goes off on another tangent. He takes us halfway across the chasm and then helicopters out of there, toodle-oo, and we look to the other side, alone, without a guide, and we wonder, “But how do I make that leap?”

More, I'm sure, to come.

How did Reagan do it? Well ...

Wednesday August 07, 2013

George W.S. Trow on 'All About Eve'

“All About Eve is a good marker in that it describes a shift from a Broadway and Hollywood studio reality to a television reality, and also a shift from a society of vanity, epitomized by Mankiewicz's heroine, Margo Channing, played by Bette Davis, to a society of narcissism, the Anne Baxter character, Eve Harrington.

”Marilyn Monroe was used as the television avatar, and she doesn't make it in the Broadway world, certainly, and George Sanders says her next move ought to be in television, and Marilyn Monroe says, 'Are there auditions in television?' She's just flunked an audition for a Broadway play, and George Sanders says, 'Yes, there are auditions in television. In fact, that's all television is.' All auditions.

“Well, so it was in 1950, and it's just a useful social marker, and I always want to refer to Diana Vreeland's famous remark, 'I loathe narcissim; I approve of vanity.' The shift from a society of vanity to a society of narcissim—not a small shift, vanity being one of those things, like sexuality itself, that humans are called upon to accept as part of their condition, and narcissism being something from another planet—and Mankiewicz is indicating not just that there's a devolution in American character but that this devolution is henceforth going to be at the top fo the American cultural hierarchy. I take Manciewicz's film very seriously, more seriously than I take Citizen Kane, which is a theatrical fantasy.”

-- George W.S. Trow, ”My Pilgrim's Progress: Media Studies 1950-1998,“ pp. 205-06

Narcissism (left) takes over from vanity (right), with television in the middle.

Friday August 02, 2013

The Enormous Mass of Facts

I read this today in George W.S. Trow's book, “My Pilgrim's Progress: Media Studies 1950-1998,” which was published in 1999:

The man of today is a citizen of the world. He seems to be ubiquitous. It is as though he had a thousand eyes and ears and, alas, only one mind. Thought has two conditions. First, knowledge as food and stimulus, second, time for distributing and digesting that knowledge. But the first is so superabundantly fulfilled that it completely obliterates the second. Knowledge comes pouring in from all quarters so rapidly that the man can hardly receive, much less arrange and think out, the enormous mass of facts daily accumulating upon him.

Yeah yeah yeah, you say. We know all that already. Move on already.

Except that's not Trow writing in 1999. That's John A. French writing in Continental Monthly in March 1864.

Here's part of the rest of his paragraph:

The boasted age of printing presses and newspapers, of penny magazines and penny encyclopedias is not necessarily the age of thought. There is a worldwide difference between knowledge and wisdom. The one consists of facts as they are, the other of facts as they may be. The one sees events, the other relations.

1864. Not only before the internet, but before television, radio, movies, the automobile. Before James Joyce. Hell, it was written, or at least published, a mere 20 years after the first telegraph message was sent in the U.S. That message: “What hath God wrought?” But even then, even in 1864, the complaint was that we had too much information besotting our brains. We had too many facts and too little wisdom.

You can take this two ways:

- Each age speeds things up enough so that the rush of information will feel overwhelming to any mind developed during the slower times of 20, 40, 60 years previous.

- We're fucked.

Saturday July 13, 2013

Calvin and Hobbes Explains FOX-News 10 Years Before FOX-News

I remember seeing this particular strip when it was first published back in the 1980s. It's only gotten more relevant.

Wednesday May 15, 2013

‘Negroes Oppose Film’: A 1921 NAACP Protest of ‘Birth of a Nation’

I love the stuff you find in The New York Times archive. It's history written in stilted language.

I was recently looking into D.W. Griffith's “Birth of a Nation” and came across this from May 7, 1921:

It's not just a world before the civil rights movement; it's a world before acronyms: Not NAACP vs. KKK but the whole thing spelled out.

The full article is available here. You can access it if you subscribe already. Which you totally should.

Wednesday April 10, 2013

How Roger Ebert is Wrong in that Sundance Clip

The clip below has been making the rounds in the wake of Roger Ebert's death last week.

At Sundance in 2003, during the Q&A after a screening of Justin Lin's “Better Luck Tomorrow,” an audience member stands up, talks about the talent on screen and on the stage, then asks, or demands, “But why, with the talent up there, and yourself, make a movie that's so empty and amoral for Asian-Americans and for Americans?”

That's when Roger Ebert stands up. Among other things, he says, “What I find very offensive and condescending about your statement is that nobody would say to a bunch of white filmmakers, ‘How could you do this to your people?’ ... Asian-American characters have the right to be whoever the hell they want to be!”

Everybody loves this clip. The presumption of the one guy, the lusty defense by the other. It's a Hollywood movie in microcosm. We have our villain (the presumptuous bastard), our hero (Roger Ebert, RIP), our stance (moral).

Question: In what way is the villain right? And in what way is the hero wrong?

Roger asks why white filmmakers don't have to justify their choices. They do, of course, but not as white filmmakers. Francis Ford Coppola and Martin Scorsese had to defend their choices as Italian-American filmmakers. Philip Roth spent a career defending his choices as a Jewish writer. Of course Coppola and Scorsese had to defend themselves from other Italian-Americans, or at least Italian-American groups, while Roth had to defend himself from Jewish groups. That's the presumption in the above clip. The questioner steps outside the racial lines we‘ve all drawn. He’s a chastising outsider in what is, at best, an internecine affair.

In a perfect world, yes, no artist, no person, is asked to embody their race, even though, in other contexts, such as the big screen on Friday (Jackie Robinson in “42”), and in the book I'm currently reading (“Hank Greenberg: Hero of Heroes”), we celebrate this. But we don't live in a perfect world.

I grew up in Minneapolis, Minn., Scandinavian descent. After college I lived for two years in Taipei, Taiwan, where I quickly realized that if I acted in such a way it wouldn't just be me acting this way. I wouldn't just be an asshole, in other words, I would be an American asshole.

Or would I? I suppose the greater question is this: Do majorities suffer from this type of myopia (seeing the one as representative of the whole) or do minorities only fear that they do? And is this fear its own form of myopia (seeing the majority as one entity) or merely common sense (people are the way they are)? This conversation isn't limited to racial matters, by the way. See: Cars/bicyclists, for example. See anything.

In the above, Roger is mostly correct. Asian-American characters do have the right to be whoever the hell they want to be. But the other dude is right, too. Justin Lin made his characters shallow and empty in a world that's already full of the shallow and empty. For that, Lin has been rewarded mightily by Hollywood. His new movie, “Fast & Furious 6,” opens in May.

Friday February 22, 2013

Want to Be Taken Seriously?

From my InBox this morning...

The key word, the word that prevents argument, is “better.” Become a good writer? I am a good writer. Become a better writer? Well, even James Joyce can't argue.

You can argue with the enticement: to be taken seriously. Is that something to be desired in this less-than-serious country? And, if desired, would becoming a better writer achieve that goal? Most writers, who work in the dark and do what we can and give what we have, assume writing is a great path to not be taken seriously. Being taken seriously involves mostly one thing; one weird trick, as they say: How much do you make?

My friend and fellow writer Andy on all the failure that goes into writing. “To get it wrong so many times,” as E.I. Lonoff said.

My favorite part of the email? “Tailored For You.”

Monday November 26, 2012

The Most Brilliant and Necessary Thing You'll See All Day: 'Onion Talks' on Social Media

This is basically my thoughts about corporations and social media. My favorite part:

“Using your brains to think of an idea and your skills to implement it? Tha's the old model. And like anything that's old and requires effort, it's inefficient.”

Sunday July 15, 2012

Making the Dish, and a Portrait of the Artist as a Stand-Up Comedian

Andrew Sullivan's blog, The Dish, linked to mine today, which is very, very cool, particularly considering how often I've read him and quoted him. I figure I still owe him about 499 posts to make up the difference. I'll get cracking.

Sullivan was interested in a post of mine from last week comparing American comedian Louis C.K. with French author Marcel Proust, both of whom, 100 years apart, talked about how technology that was once considered amazing (the phone and smartphone), each became, very quickly, a subject for complaint. For this, Proust called us “spoilt children.” Louis C.K. is a bit more florid, calling us “the shittiest generation of piece-of-shit assholes that ever fucking lived.” Proustian.

I came across the Proust quote in Alain de Botton's book, “How Proust Can Change Your Life,” which is particularly good in the early chapters, particularly Chapter 3, “How to Take Your Time.” That, of course, is another piece of advice from Louis C.K.: “Give it a second,” etc.

I'm not surprised, by the way, that there's this connection between the early 20th-century French author and the early 21st-century American stand-up comedian. In de Botton's book, Proust is quoted as saying that artists are...

...creatures who talk of precisely the things one shouldn't mention.

And that's what the best stand-up comedians are, too. They stand before us and tell us uncomfortable truths to make us laugh. If it's done poorly and without empathy, you get Daniel Tosh earlier this week or Michael Richards a few years back. If it's done well, you get Louis C.K., Ricky Gervais, Chris Rock, Eddie Murphy and Richard Pryor.

“Take your time” vs. “Give it a second”

Sunday April 29, 2012

IMDb's Trivial Problem

On IMDb.com, if you have someone writing your bio for you, as someone named Larry-115 apparently did for Paris Hilton, then on your credits page you'll have a link reading “See full bio,” which will lead you to, in this case, Larry-115's bio of Ms. Hilton and all relevant material, such as nicknames, height and “That's hot.”

If you don't, as acclaimed Iranian filmmaker Jafaar Panahi doesn't, you'll simply have a link reading “See more trivia.”

As a result, Paris Hilton's pampered, celebrity life is considered “a bio,” while Panahi's arrest and conviction by Iranian authorities, which has been protested worldwide by every filmmaker and filmmaking body, as well as heads of state, is considered “trivia.”

A micro example of a macro problem. Two macro problems, actually: automation isn't concerned with nomenclature; and modern culture has turned on its head what is significant and what is trivial.

Saturday April 21, 2012

Sharing a Birthday with Hannibal Lector

Thanks to FlavorWire's infographic on the birthdays of famous (and not-so-famous) fictional characters, I know now I share a birthday with Hannibal Lector. We'll be serving fava beans, a nice chianti, and... not sure what kind of meat yet. No worries, though. Our butcher gets the freshest cuts.

Via the same infographic: my father gets MacGyver, which is so wrong (the show is schlock and Dad can hardly change a lightbulb), my Mom gets Jean-Luc Picard (whom I'm sure she's never heard of), while Patricia, poor Patricia, hardly a sci-fi fan, winds up with lesser sci-fi: Daniel Jackson of “Stargate SG-1.” Even *I* don't know who that is.

Nephews Jordy and Ryan share days with, respectively, Dr. Watson and Captain America. (That's more like it!) Grown-up nephew Casey gets Martin Riggs of “Lethal Weapon.” My sister Karen? Rick Peterson, “East Enders.” (Got nothing.) My brother Chris probably gets the best birthday companion: The King of Earth from “Time Stranger Kyoto.” I don't know who that is but it sounds impressive.

You?

Time for the birthday cake, Clarice.

Wednesday February 08, 2012

Black History Month Linkage

I have no profound thoughts on black history month, the shortest month of the year, other than to hope that someday it won't be necessary.

In the meantime, lamely, I offer past articles that touch on some of the issues this month touches on:

- A 2003 Seattle Times review of Library of Congress' epic, two-volume, two-thousand-page tome, “Reporting Civil Rights: American Journalism: 1941-1972,” which gives us the history before it's history, and before it's been sweetened and commodified and forgotten. One of the more important books you can read about the civil rights movement.

- A 1998 Seattle Times review of David Halberstam's “The Children,” which focuses on the Nashville sit-in kids, including future U.S. Congressman John Lewis and future DC Mayor Marion Berry.

- A 1997 personal review of Jules Tygiel's seminal book, “Baseball's Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and his legacy.”

- A short, personal review of Henry Louis Gates' “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Black Man.”

- A 2008 personal review of Barack Obama's “Dreams From My Father.”

- A 2005 MSNBC article on actor Jeffrey Wright.

- A 2006 MSNBC analysis of the career of director Spike Lee.

- A 2007 MSNBC paean to Morgan Freeman.

- A 2008 MSNBC dissection of the secret to Tyler Perry's success.

In “Reporting Civil Rights,” Russell Baker reminds us that by the time Dr. King spoke, “huge portions of the crowd had drifted out of earshot,” while civil-rights worker Michael Thelwell details how the Kennedy administration turned the March into something “too sweet, too contrived, and its spirit too amiable to represent anything of the bitterness that had brought the people there.”

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)