Movie Reviews - 2012 posts

Monday December 10, 2012

Movie Review: Dark Shadows (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“This thing is spectacularly off,” I said.

“I keep waiting for it to find a rhythm,” Ward responded, “and it never does.”

We were halfway into Tim Burton’s “Dark Shadows,” surely one of the worst movies of the year. The cast was good, the trailer looked funny, the reviews were OK. In The New York Times, Manohla Dargis called it enjoyable; on Salon, Andrew O’Hehir trumpeted Michelle Pfeiffer’s return to the screen (after only a year away?), while on Slate, Dana Stevens wrote, “[Burton] and Depp, both avowed childhood fans of the original series, seem to be in their element and having a grand old time.” Turns out these positive reviews were in the minority. Among top critics on Rotten Tomatoes, “Dark Shadows” garnered a 37% rating, which, to me, is still 37 percentage points too high. It’s an abysmal movie.

Sleepy, Hollow

It opens with 10 minutes of backstory. In the 18th century, the Collins family, including young Barnabus, leave Liverpool, England, for the wilds of Maine, where they start a fishing empire, create the town of Collinsport, and build the stately, gothic mansion known as Collinwood.

It opens with 10 minutes of backstory. In the 18th century, the Collins family, including young Barnabus, leave Liverpool, England, for the wilds of Maine, where they start a fishing empire, create the town of Collinsport, and build the stately, gothic mansion known as Collinwood.

Barnabus, of age now, and played by Johnny Depp, is about to diddle the servant, Angelique (Eva Green), who asks if he loves her. He cannot tell a lie: he doesn’t. Hell hath no fury like a woman—or, in this case, witch—scorned, and she uses her powers to kill his parents by falling steeple. Distraught, he descends into the black arts, but manages, through the pain, to find his one true love: Josette (Bella Heathcote, this decade’s Heather Graham). Ever jealous, Angelique compels Josette to throw herself off Widow’s Hill, turns Barnabus into a vampire, then turns the town against him. A torch-wielding mob descends, chain him in a coffin, and bury him alive for 200 years. Cue credits.

It’s now 1972. A young woman on a train, who looks like Josette (same actress), is obviously hiding something (she changes her name, per a Victoria, B.C. travel poster, to Victoria Winters), and heading for a job as a governess at Collinwood, now decrepit. There, she and we meet the modern, dysfunctional Collins family: matriarch Elizabeth (Pfeiffer), who is starched and overly proper; her eye-rolling teenage daughter, Carolyn (Chloe Grace Mortez); Elizabeth’s brother, Roger (Jonny Lee Miller), a weak, shallow man who ignores the needs of his son, David (Gulliver McGrath), whose mother died at sea three years earlier. David claims he still sees his mother; he claims he still has conversations with her. That’s why Collinwood has an in-house shrink, Dr. Julia Hoffman (Helena Bonham Carter, of course), who arrives at evening meals frequently plastered. There’s also a disgruntled butler/handyman, Willie (Jackie Earle Haley), who is frequently plastered, and whose every joke falls flat.

Barnabus Returns

Only after meeting all of them, as well as the ghost of Josette who plagues Victoria, do we get the resurrection of Barnabus by a night-time construction crew, each of whom screams, runs and crawls from this nightmare. Barnabus then goes to Collinwood and we meet the family all over again: Elizabeth, Carolyn, Roger, et al. Elizabeth wants to keep Barnabus’ secret—that he’s a 200-year-old vampire—from everyone, including the family, so she introduces him as Barnabus III. From England. All of these jokes fall flat. Then Barnabus meets the new governess, Victoria, who looks exactly like his long-lost true love, Josette, and discovers that his nemesis, Angelique, has survived all of these years and is now running the town.

What does he do? Get revenge on Angelique? Court Victoria, who looks like his one true love?

Neither. He sets about restoring the family name and reputation. We get a montage—backed by the Carpenters’ “Top of the World”—of workers sprucing up Collinwood and the Collins Canning Factory opening its doors again. When Barnabus finally meets Angelique, she makes a pass at him; the second time they have rough sex. He also sucks the blood out of a band of hippies in the woods. Then he kills Dr. Hoffman, who, under the pretense of curing him of vampirism, and wanting eternal youth, tries to turn herself into a vampire. Before this, she goes down on him. Later, Barnabus throws a ball headlined by Alice Cooper. “Balls are how the ruling class remain the ruling class,” he says.

His revenge? Forgotten. His one true love? Whatever. What should be driving the story forward isn’t, and what is driving the story forward isn’t funny.

Occasionally we get bits where Barnabus grapples, to humorous effect, with 1972 mores. He sees the golden-arched “M” of McDonald’s as a sign of Mephistopheles. He wonders over the sorcery of television and yells at Karen Carpenter, singing on a variety show of the day, “Reveal yourself, tiny songstress!” In Dr. Hoffman’s office, he shakes his head and says, “This is a very silly play.” Cut to: an episode of “Scooby Doo.”

But most of the movie is scattered, pointless, painfully tin-eared.

Beetlejuiceless

All of it leads to a final confrontation between the Collins family and Angelique, where we find out, in a pointless third act reveal, that long ago Angelique turned Carolyn into a werewolf. We also find out that it was Angelique who killed David’s mother at sea. At this point David’s mother finally reveals herself, in all her howling fury, and destroys Angelique.

Why didn’t David’s mother do this sooner? Why didn’t Barnabus? Why do the Collinses consider Barnabus worthy of the portrait over the fireplace when it was Barnabus’ father who built up everything? And since when do witches turn men into vampires?

The fault isn’t Depp’s: his line readings; his reaction shots, are generally good. But nothing anyone else does is worth a damn. Tim Burton lets his freak flag fly. He paints Johnny Depp chalky white again, as in “Edward Scissorhands,” “Ed Wood,” “Willie Wonka,” and “Sweeney Todd.” He has the living and the dead raise a family again, as in “Beetlejuice.” But there’s no juice here. Burton’s always been a lousy storyteller, sacrificing plot and plausibility for imagery, but even the imagery here feels stale. Burton’s love of the dead finally feels dead.

My favorite moment? The end. And not because it’s the end but because of the Hollywood hubris it represents. As Barnabus and Victoria, both vampires now, kiss on the rocks beneath Widow’s Hill, the camera dives underwater and heads out to sea, where we come across the body of Dr. Hoffman in cement shoes. And her eyes suddenly open. Ping! The end. It’s a set-up for a sequel that will never be made. It’s an ending that assumed a success that never came.

Thursday December 06, 2012

Movie Review: Lincoln (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

You know the saying that laws are like sausages—you don’t want to see them being made? Tony Kushner says, “Grow up.” Steven Spielberg says, “We’ll loin ya.” Their movie, “Lincoln,” is not only the greatest story ever told about the passage of a law—in this case the 13th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which formally, legally abolished slavery—it’s a joy for anyone who cares about great acting, writing, and drama. It’s what movies should be.

In 1915, Pres. Woodrow Wilson called “The Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s Confederate-friendly epic, “history written with lightning,” but I wouldn’t call this movie that. It’s history written as carefully as history should be. It’s well-researched and made dramatic and relevant. Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), the most saintly of all presidents, isn’t presented here as a saint but as a smart, moral, political man, who, under extraordinary pressure from all sides, does what he has to do in order to do the right thing. His machinations aren’t clean. It takes a little bit of bad to do good. Progress is never easy. There are always slippery-slope arguments against it. Sure, free the slaves. Then what? Give Negroes the vote? Allow them into the House of Representatives? Give women the vote? Allow intermarriage? The preposterousness of where the road might take us prevents us from taking the first step. Then and now.

In 1915, Pres. Woodrow Wilson called “The Birth of a Nation,” D.W. Griffith’s Confederate-friendly epic, “history written with lightning,” but I wouldn’t call this movie that. It’s history written as carefully as history should be. It’s well-researched and made dramatic and relevant. Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis), the most saintly of all presidents, isn’t presented here as a saint but as a smart, moral, political man, who, under extraordinary pressure from all sides, does what he has to do in order to do the right thing. His machinations aren’t clean. It takes a little bit of bad to do good. Progress is never easy. There are always slippery-slope arguments against it. Sure, free the slaves. Then what? Give Negroes the vote? Allow them into the House of Representatives? Give women the vote? Allow intermarriage? The preposterousness of where the road might take us prevents us from taking the first step. Then and now.

Nobody does it better

I once said of Jeffrey Wright’s Martin Luther King, Jr., that no one would ever do it better; I now say the same of Day-Lewis’ Lincoln. He only has to talk about his dreams to his wife, Mary Todd (Sally Field), with his stockinged feet up on the furniture, a kind of languid ease in his long-limbed body, and I’m his. He only has to quote Shakespeare one moment (“I could count myself a king of infinite space were it not that I have bad dreams”), and, in the next, ask Mary, in a colloquialism of the day, “How’s your coconut?” and I’m his. I remember when I was young, 10 or so, and we were visiting my father’s sister, Alice, and her husband, Ben, and when we had to leave I began to cry. Because I didn’t want to leave Uncle Ben. I liked being near him. He had a calm and gentle spirit that I and my immediate family did not. It felt comfortable to be around. I got that same feeling from Daniel Day-Lewis here. How does he do that? How do you act a calm and gentle spirit?

His Lincoln exudes charm. During a flag-raising ceremony, he pulls a piece of paper from his top hat, says a few quick words, then looks up with a twinkle in his eye. “That’s my speech,” he says, and returns the paper to his top hat. He gives his cabinet, reluctant to spend political capital on another go at the 13th amendment, which the House failed to ratify 10 months earlier, a primer on the legal difficulties of the Emancipation Proclamation. If slaves are property, then… If the Confederacy is not a sovereign nation but wayward states, then… Finally he apologizes for his long-windedness: “As the preacher said, I would write shorter sermons but once I get going I’m too lazy to stop.” He says it with a twinkle in his eye. His stories are there for purposes of instruction and/or distraction. Maybe he does it to distract himself. In the war room late at night, waiting on word about the shelling of Wilmington, Va., a blanket around his shoulders and a cup of coffee in his hand, he launches into an anecdote about Revolutionary War hero Ethan Allen, and Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton (Bruce McGill), loudly objects. “You're going to tell one of your stories! I can't stand to hear another one of your stories!” He leaves. Too bad. He missed a great story. Added bonus: You get to hear Day-Lewis, an Englishman, acting as Lincoln, an American, imitating an Englishman.

If this Lincoln is human-sized so is the presidency itself. Petitioners line up outside Lincoln’s office to ask for favors. His cabinet is full of men who think they should be president and aren’t reluctant to share their opinions. His wife has her complaints (their son, Willie, dead now three years), his son Robert has his (he wants to leave law school for the war), Negro soldiers have theirs (they’re getting paid $3 less per month than white soldiers). Both political extremes mock him. Abolitionists consider him cautious and timid, a lingerer and a buffoon, while the Northern Democrats malign him as a tyrant enthralled to the Negro. They thunder about him in Congress. “King Abraham Africanus!” they cry. A president considered too conciliatory by friends and an African tyrant by foes? Plus ca change.

Peace v. Freedom

Ultimately “Lincoln” is about the choice between peace (for all) and freedom (for a few). “It’s either this amendment or the Confederate peace,” Secretary of State William Seward (David Strathairn), tells the president. “You cannot have both.”

Almost everyone pushes Lincoln toward peace even as he moves, in his methodical, searching manner, toward freedom. He gave himself the power during war to proclaim all slaves free, but what happens in peace? Won’t slavery still be legal in the South? Couldn’t the Civil War just happen all over again over the same issue?

The 13th amendment has already passed in the Senate and it’s just 20 votes shy in the House. So early in January 1865, even as he sends moderate Republican Preston Blair (Hal Holbrook) to Virginia to set up a potential peace conference with secessionist delegates, Lincoln hires, or has Seward hire, three scallywags (read: lobbyists), gloriously headed up by James Spader as W.N. Bilbo, to more or less buy the votes of lame-duck Democrats, losers of the 1864 election, who have nothing to lose and gainful employment to gain.

That’s the true drama of the movie. Can Lincoln, in the midst of pulling back the South to the Union, hold together enough of the disparate elements that remain to abolish slavery at the federal level before the South returns and gums up the works again? We get a few key moments, several dramatic scenes. The Northern Democrats attempt to goad thundering abolitionist Thaddeus Stevens (Tommy Lee Jones), who doesn’t suffer fools gladly, into proclaiming on the House floor that he believes in the equality of races (anathema at the time) and not just equality before the law.

You know all of those “100 Greatest Movie Insults” compilations on YouTube? They need an update. This is Stevens’ rejoinder:

How can I hold that all men are created equal when here before me stands, stinking, the moral carcass of the gentlemen from Ohio, proof that some men are inferior, endowed by their maker with dim wit impermeable to reason, with cold, pallid slime in their veins instead of hot, red blood. You are more reptile than man, George! So low and flat that the foot of man is incapable of crushing you.

What fun. The language here is beautiful. I also like it when Lincoln calls his cabinet “pettifogging Tammany Hall hucksters.” We need to bring that back: “pettifogging.” We need to bring back erudite insults.

But the key scene in the movie contains no thunder, and the key man who needs convincing isn’t a Democrat; it’s Lincoln himself.

Self-evidence

As with the Ethan Allen story, it takes place in the middle of the night in the basement of the White House. Lincoln is about to send a message in Morse code about the “secesh” delegates, and ruminates out loud with several officers. Up to this point he’s been pursuing two paths, one leading to peace but not passage, the other pointing to passage but not peace, and this is the point where the paths diverge and he has to choose which to walk on. He begins down the path of peace: bring the delegates to Washington. But before the message is sent, he engages the two men in conversation.

One of them, it turns out, is an engineer. Lincoln asks him if he knows Euclid’s axioms and common notions, and then regales them with the first: Things which are equal to the same things are equal to each other. “That’s a rule of mathematical reasoning,” he says. “It’s true because it works. Has done and always will be.” He seems to be talking out loud. But there’s a moment, an epiphanic “huh,” when Lincoln realizes the point he’s talking toward:

In his book, [huh] Euclid says this is self-evident. You see, there it is, even in that 2,000-year-old book of mechanical law: It is a self-evident truth that things which are equal to the same things are equal to each other.

The beauty of the scene? Kushner and Spielberg draw no line to the Declaration of Independence. They assume we’re already drawing that line ourselves. They assume it’s self-evident. They just give us Daniel Day-Lewis saying “Huh.”

At which point he rescinds the order sending the peace delegates to Washington, and thereby changes history.

To the ages

“Lincoln” isn’t all glory. The screenplay by Tony Kushner attempts to demythologize history, the presidency and Lincoln, but Spielberg, fore and aft, can’t contain his myth-making tendencies.

In the beginning, sitting on a raised platform, Pres. Lincoln engages four soldiers, two black and two white, and seems halfway to Memorial already. Three of the four soldiers have the Gettysburg Address memorized already, as if they were 20th-century schoolkids (Dan Roach and myself in fifth grade) rather 19th-century soldiers. We hear tinkling music as if in a Ken Burns documentary. It’s all rather unnecessary. We could’ve begun with Lincoln’s bad dream and stockinged feet and gotten on with it.

Then there’s the ending. Spielberg has always had a problem with endings. From behind, with music swelling, we watch Lincoln leave the White House, on April 14, 1865, late for Ford’s Theater. “Not a bad end,” I thought. But it’s not the end. We go to the theater, but it’s a different theater, one his son Tad is attending, which suddenly closes its curtains to announce the awful and inevitable. Then there’s a deathbed scene: Mary wailing, the doctor declaring, blood on the pillow, someone saying, as someone maybe said or maybe didn’t, “Now he belongs to the ages.” The end? No. Spielberg has to include the second inaugural: “With malice toward none, with charity to all…” Meanwhile I sat in my seat, feeling not very charitable.

But those are my only complaints about “Lincoln.”

Monday December 03, 2012

Movie Review: Hitchcock (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Good evening.

It’s been quite a year for Alfred Hitchcock, hasn’t it? His film, “Vertigo,” a box-office bomb when it was released in 1958, was voted the greatest film of all time by the 846 critics, distributors and academics commissioned by Sight & Sound magazine, supplanting “Citizen Kane,” which had ruled atop that prestigious list for decades. Then HBO premiered its movie, “The Girl,” about Hitchcock’s obsession with Tippy Hedren, his star of “The Birds” and “Marnie.”

Now this.

If “The Girl” focuses on the girl and was a drag, “Hitchcock” focuses on Hitchcock and is fun. It begins and ends fun anyway. Near the end, Mrs. Hitchcock, Alma Reville (Helen Mirren), tells her husband (Anthony Hopkins) that they’ve been “maudlin” with each other for too long. Indeed. That’s the problem with “Hitchcock.” It, like Hitchcock himself, has a maudlin middle.

If “The Girl” focuses on the girl and was a drag, “Hitchcock” focuses on Hitchcock and is fun. It begins and ends fun anyway. Near the end, Mrs. Hitchcock, Alma Reville (Helen Mirren), tells her husband (Anthony Hopkins) that they’ve been “maudlin” with each other for too long. Indeed. That’s the problem with “Hitchcock.” It, like Hitchcock himself, has a maudlin middle.

Family plot

Why are they Mr. and Mrs. maudlin? Because after 30 years Alma is suddenly upset by her husband’s obsessions with his leading ladies, the so-called Hitchcock blondes, including Madeleine Carroll, Ingrid Bergman, Grace Kelly, Eva Marie Saint, and now, here, Janet Leigh (Scarlett Johansson). To get back at him, she succumbs to the attentions of hack-writer Whitfield Cook (Danny Huston), who adapted “Strangers on a Train” for Hitchcock (apparently poorly), and who is now working on a project called “Taxi to Dubrovnik,” which, in real life, was published as a novel in 1981. At a beach cottage, she agrees to collaborate on it with him. She likes the way he flirts with her. She likes the attention he pays to her. Attention must be paid. But her absence distracts the great man from his work, the film “Psycho,” for which they, the Hitchcocks, are mortgaging their house. It also distracts him from his obsessions, such as peeking through the blinds of his Paramount office at the would-be Hitchcock blondes walking by. Instead, Hitch becomes obsessed with Alma.

Even before Alma began disappearing up the coast, though, Hitch hardly seems obsessed with his leading lady. He doesn’t stare at her 8x10 glossy the way he does with Grace Kelly’s. He doesn’t spy on her in the dressing room through a peephole, as he does with Vera Miles (Jessica Biel), prefiguring, of course, Norman Bates’ own voyeurism in “Psycho.” He isn’t upset with her, disappointed in her, the way he was with Miles, whom he was going to make a star in “Vertigo,” until she betrayed on him, cheated on him you might say, by getting pregnant. He doesn’t maul her in the backseat of a limo as he does with Tippi Hedren in HBO’s “The Girl.” You know what he does? He shares candy corn with her in the front seat of her Volkswagen. Cute. So what’s Mrs. Hitchcock’s problem? That’s the real disconnect of the movie. It doesn’t answer one of the main questions of drama: Why now? If anything, everything points to it not being now. Everything they own is riding on “Psycho.” Shouldn’t Alma be riding with it? Instead of succumbing to the fatuous flirtations of Danny Huston?

The wrong man

Worse, Alma’s sad beachfront needs distract us from what may be a better movie. Because while Hitchcock is acting the perfect gentleman with Ms. Leigh, or the cuckolded husband with Alma, he is having imaginary conversations with none other than Ed Gein (Michael Wincott), the Wisconsin mass murderer on whom Norman Bates is based. That’s pretty creepy. Ed Gein is to Hitchcock here as Humphrey Bogart is to Woody Allen in “Play It Again, Sam.” He gives him advice. He taunts him to action. Ed Gein. Yet Hitch remains toothless despite it. He remains a charming but naughty waddler of a man. It seems you should go one way or the other: deeper into the similarities and differences between Gein and Norman and Hitchcock (and us, by the way; they keep leaving out us, the movie audience, the true voyeurs, as Hitchcock never did); or maybe you replace Gein-as-counselor with Norman Bates, who, being fictional, would be lighter, and fit better into the overall tone of the movie.

Instead, it’s a movie of distraction. It’s a movie that keeps skimming surfaces.

In a way, it’s about how the French were wrong after all. Hitchcock wasn’t an auteur the way they said. He needed Alma, and he needed Bernard Hermann’s score (Wirt! Wirt! Wirt!), and he needed all the other talent around him, not least Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh. But mostly he needed Alma. He owns up to this at the premiere of “Psycho.” Alma, who is used to staying a few paces behind the great man, is here called forward to share in the acclaim, and they have the following conversation that sums it all up rather neatly:

Alfred: I’ll never find a Hitchcock blonde as beautiful as you.

Alma: I’ve waited 30 years for you to say that.

Alfred: And that, my dear, is why they call me ‘The master of suspense.’

It’s a charming bit that I didn’t believe at all.

Sabotage

The movie begins and ends similarly, with Ed Gein murdering his brother with a shovel in 1941, and the camera panning over to, yep, Alfred Hitchcock, who, in “Alfred Hitchcock Presents…” fashion, speaks to us directly about Cain and Abel, and brotherly murders, and the connection between Gein and “Psycho,” and what we’re about to watch. It’s the macabre served with a wink. The movie ends happily, with Hitchcock in front of his southern California home, which, with the success of “Psycho,” he gets to keep, and wondering over his next project. He’s looking for inspiration. “I do hope something comes along,” he says. At which point a crow settles on his shoulder. “Good evening,” he says to us.

Now that’s fun. Hopkins is fun. He’s less one-note than two-note, but both are fun notes.

Mirren is good, too, but most of her notes—her various carping, her hope for an affair with Danny Huston—are not fun, and at odds with the tone of the rest of the movie.

It’s a shame because I liked almost everything else in “Hitchcock”: the battles with Paramount head Barney Ballaban (Richard Portnow); the battles with censor Geoffrey Shurlock (Kurtwood Smith); Hitchcock’s conversations with legendary agent Lew Wasserman (Michael Stuhlbarg), who deserves a movie of his own. I liked all of this backset intrigue. I left the theater with a smile.

But the movie is a little like Alfred Hitchcock, the man, divided into thirds. We got a bit of the head (the dry wit), and a bit of the lower depths (the peeping voyeurism; the Scottie Ferguson dress-up games), but too much of that overweight, maudlin middle.

Friday November 30, 2012

Movie Review: Wreck-It Ralph (2012)

WARNING: SEV-2 SPOILERS

“Wreck-It Ralph” is about what happens to video-game characters after you leave the arcade. It’s “Toy Story” for the digital age.

Not as good, of course. It’s got some wit and laugh-out loud moments. If you’re a parent and your kid wants to go, I’m sure you’ll appreciate it. If you’re a gamer or computer geek, I’m sure you’ll appreciate it on a deeper level than I did. But I’m neither parent nor gamer so I thought it was merely … OK.

Bad-Anon

Our protagonist and title character is Wreck-It Ralph (John C. Reilly), the low-brow, fist-heavy bad guy of the 30-year-old arcade game “Fix-It Felix Jr.” In pixilated low-def, Ralph wrecks a building and Felix (steered by the user, and voiced by Jack McBrayer of “30 Rock”) fixes it; then the residents of the building give Felix a medal, pick up Ralph, and throw him off the roof and into the mud below.

Our protagonist and title character is Wreck-It Ralph (John C. Reilly), the low-brow, fist-heavy bad guy of the 30-year-old arcade game “Fix-It Felix Jr.” In pixilated low-def, Ralph wrecks a building and Felix (steered by the user, and voiced by Jack McBrayer of “30 Rock”) fixes it; then the residents of the building give Felix a medal, pick up Ralph, and throw him off the roof and into the mud below.

Problem? Ralph is tired of being the bad guy. Even at the end of the day, when the kids go home and the characters are free to do what they want, Felix is feted by the building’s residents while Ralph drags himself to the nearby dump and sleeps on a pile of rocks. He airs his complaints at Bad-Anon, a support group for video-game villains (including one of the ghosts from Pac-Man), who end each meeting with this affirmation:

I’m bad and that’s good.

I will never be good and that’s not bad.

There’s no one I’d rather be than me.

But he’s still lonely. When the building’s residents hold a 30th anniversary party, he crashes it, gets into an argument with Gene (Raymond S. Persi), the mustached fussbudget, and splatters the celebratory cake everywhere with his massive fists. Then he declares he’ll win a medal like Felix and show everyone.

Whither Q*bert?

A few rules of this universe. If a character dies outside their video game they die for good. No regeneration. And if they don’t make it back to their video game in time, they risk the dreaded “Out of Order” sign, which is a step away from being unplugged; then they’ll be forced to fend for themselves in a kind of video-game port authority, with surge protectors policing the area and unplugged characters, such as Q*bert, begging for handouts. Finally, if you try to insert yourself into someone else’s video game, that’s called “going Turbo,” after the character Turbo, who headed up the most popular racing game of the early ’80s. Then another game became more popular so he tried to take it over, which led to both games being unplugged. Lesson there.

Which Ralph, being Ralph, ignores. He learns a medal awaits the winner of “Hero’s Duty,” a high-def, first-person shooter game, and he immediately steals the dark-metal spacesuit of one of its soldiers, then mucks up the game. Worse, he rides, or is ridden by, a spaceship with a Cy-Bug attached, and they wind up in Sugar Rush, a brightly colored, girly, racing game, where the Cy-Bug begins to lay eggs and Ralph quickly loses the medal to a sassy sprite named Vanellope (Sarah Silverman). She sees it as a coin with which she can enter a race, which she’s never done since she’s a glitch: fading in and out of view. But she feels racing is in her code.

For a time they team up. Ralph helps Vanellope train so she can win the race and get his medal back. But then the ruler of Sugar Rush, King Candy (Alan Tudyk doing Ed Wynn), warns him that if Vanellope wins or places, she’ll become a user choice; and when she glitches they’ll complain; and the game will be unplugged and everyone will be forced to leave. Except Vanellope, who, as a glitch, can’t leave the game. She’ll die with it.

Burdened with this news, Ralph, stricken, does what he does best: his big fists wreck Vanellope’s car. It’s his first heroic act of the movie but he’s never felt more like a bad guy.

Worse, when he returns to his own game, an “Out of Order” sign is taped to the window. His absence was noted by gamers, the sign affixed, and Felix Jr., a kind of gee-whiz good guy, went in search of him. Now everyone’s gone. Everyone but Gene, who fussily commends Ralph on his medal before leaving for good.

Cleverbot

This is about when the movie got interesting for me. Up to this point, Ralph has been an unsympathetic character in pursuit of a pathetic goal. But when he heaves his medal against the “Out of Order” sign on the opposite side of the glass, it tilts, and beyond it he sees Vanellope’s face on the “Sugar Rush” game. And a light goes on. If Vanellope was a glitch, why would she be pictured on the game? Now Ralph’s got a better motivation than getting a medal. He needs to find out what King Candy is up to and save Vanellope in the process.

Ready for the big spoilers? King Candy is really Turbo, Vanellope is really a princess, and during the big race the Cy-Bugs hatch and attack. Sugar Rush is defended by Calhoun (Jane Lynch), the hard-ass fem-babe of “Hero’s Duty,” and, most of all, by Ralph, who, through the magic of coca-cola and Mentos, eliminates the Cy-Bugs and Turbo. Order is restored. Felix and Calhoun kiss. Everyone lives happily ever after.

But it’s not clever enough. It’s got clever bits but Pixar movies are steeped in it. This feels like a corporation, the Disney corporation, using its corporate mentality to try to ape the individualistic, artistic sensibility of a company like Pixar. A lot of what they come up with is derivative, a lot is broad, too many opportunities are missed.

The voicework, particularly by Silver, Brayer, Lynch and Tudyk, is fantastic. But our main character? Ralph? And John C. Reilly’s voice that went with him? Annoyed me throughout. I never liked him. I never even felt sorry for him. And I’ve felt sorry for some pretty despicable characters in the movies.

In another lifetime I worked in the video-game industry. I was a software test engineer in the early days of Xbox, working on Xbox-specific sports games like “NFL Fever” and “NBA Inside Drive.” I was the non-gamer in the group, there by accident, a kind of glitch myself, and my job was to find bugs and label them according to severity or “sev.” Sev 1 bugs crash the game, sev 2 bugs halt it in some fashion, sev 3s are annoying, sev 4s are merely suggestions that tend to get ignored by the developer.

I’d label Ralph somewhere between a sev 2 and sev 3 bug. He’s annoying and he halts the movie for me. He’s bad and that’s not good.

I know. By Design.

Monday November 26, 2012

Movie Review: Flight (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Flight” has an obvious double meaning: both Southjet flight #227, with 102 passengers on board, which Capt. Whip Whitaker (Denzel Washington) lands in a Georgia field after a mechanical failure, saving all but six people; and Whitaker’s subsequent flight from the knowledge, the lifelong knowledge, that he’s a drunk and an alcoholic, and that he landed the plane under the influence, and now people know.

The trailer really plays up the hero angle, doesn’t it? I went back and looked at it again. It implies that “Flight” is a movie about a heroic pilot who saves 100 lives in a derring-do, upside-down, crash landing—thrillingly filmed by director Robert Zemeckis and DP Don Burgess—and then runs into some bullshit. But the movie’s about the bullshit. And it’s not bullshit.

Feelin’ Alright

The movie opens at 7:14 AM—an homage to Babe Ruth or “Dragnet”?—as Whitaker is awakened by his iPhone. His bed partner, flight attendant Nadine (Katerina Marquez ), is awakened, too; and while he staggers his way through a conversation with his ex-wife, she walks back and forth, stunning us with her nakedness. At one point she bends over. “I’ve been up since … the crack of dawn,” Whit says to his ex-wife. It’s his first lie in the movie. At least it’s a witty one. Is there a reason for this nakedness other than the “wow” factor? Is it designed to make us feel guilty? Distracted? We thought we were seeing a Denzel Washington character study and suddenly we’re waylaid by this naked beauty.

The movie opens at 7:14 AM—an homage to Babe Ruth or “Dragnet”?—as Whitaker is awakened by his iPhone. His bed partner, flight attendant Nadine (Katerina Marquez ), is awakened, too; and while he staggers his way through a conversation with his ex-wife, she walks back and forth, stunning us with her nakedness. At one point she bends over. “I’ve been up since … the crack of dawn,” Whit says to his ex-wife. It’s his first lie in the movie. At least it’s a witty one. Is there a reason for this nakedness other than the “wow” factor? Is it designed to make us feel guilty? Distracted? We thought we were seeing a Denzel Washington character study and suddenly we’re waylaid by this naked beauty.

At which point Whip hangs up, finishes his beer, snorts some cocaine and gets ready to fly an airplane in bad weather. Yeah, “Flight” won’t be your in-flight movie anytime soon.

So we know his problem from the get-go. Would the movie have been better if, like the trailer, it had engaged in a little subterfuge? If it had begun with Capt. Whitman entering the cockpit, the conversation there, the cup of coffee? We think we’re watching the story of a hero and object when the railroading begins. Until we realize it isn’t railroading.

The straightforward approach has the advantage of being straightforward. It has the disadvantage of not surprising us much.

The soundtrack doesn’t help. Whip’s drunk/coked-up walk to the airplane is accompanied by Joe Cocker’s “Feelin’ Alright (Not feeling too good myself).” His first visitor in the hospital is Harling Mays (John Goodman), friend and drug dealer, whose entrance is accompanied by the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.” As foreplay at Whip’s farm? Marvin Gaye.

Sympathy for the Devil

Harling is an interesting character. He’s essentially a bad person, the man who keeps Whip on the wrong path, but we like him because he’s John Goodman. He bosses around the nurse, calls her “Nurse Ratched,” and, when she’s gone, leaves Whip some smokes and “stroke mags.” He would’ve left vodka, too, but Whip tells him to take it with him. He’s in shock at this point. He’s trying to change. Six people died on his watch, including Nadine. And now the NTSB (National Transportation Safety Board) knows about his problem. They took blood from the flight crew, including those, like Nadine, who didn’t survive, and they know about the booze and coke. What we don’t know, what we don’t find out until a late-morning meeting between the pilots’ union rep (Bruce Greenwood), Hugh Lang (Don Cheadle), a quiet-but-tough Chicago lawyer, and Whip, is that Whip’s blood-alcohol level was .24. That’s three times the legal limit to drive. A car. He’s facing criminal negligence and manslaughter charges.

Pursued by the media, pursued by his demons, Whip tries to remove all evidence of his problem. At the family farm, where he learned to fly in a Cessna 172 crop duster, he gets rid of all the booze: beer, wine, hard liquor. He gets involved in a relationship with Nicole (Kelly Reilly), a red-headed masseuse and heroin addict whom he met in the stairwell of the hospital, and whose story, pre-crash, had been intercut with his. She goes to AA meetings. He falls off the wagon in a bad way. If he was ever on it.

As bad as we thought he was? He’s worse. Denzel is amazing here. The overwhelming confidence he brings to his characters is cut in half, and laced with doubt and guilt. He’s overweight and out-of-shape but you see it more in the way his face crumbles. His mouth doesn’t work right and his chin recedes. Screenwriter John Gatins is an alcoholic himself and he gets all the excuses right. “What, you want to count the fucking beers?” he says to Nicole. “I choose to drink,” he says to everyone, particularly himself. Watching Denzel, I got flashbacks to the alcoholics I’ve known. It’s not like Goodman. There’s no charm here. There’s just sadness and disgust.

The movie builds toward a public hearing before the NTSB and we find ourselves in Whip’s shoes, rooting for him to get away with it. I caught myself doing this several times and consciously reversed course. No, get caught, motherfucker. For you and the people who know you.

The reckoning is predictable, and of Whip’s choosing. He has his “one too many lies” moment. He can’t tell another. In the end he can’t lie about Nadine, the girl he was with in the beginning, and who never made it out of Flight #227.

What’s Going On?

There are some great supporting performances here, particularly Goodman, Cheadle, Melissa Leo as the NTSB investigator and James Badge Dale as a cancer patient, and of course Denzel dominates, but the movie’s too long. 138 minutes? I would’ve cut Nicole’s whole backstory—shooting up, trouble with the scuzzy landlord, blah blah—as well as Whip’s final scene with his son, and ended it with him talking to his fellow prisoners: “For the first time in my life I’m free.” When he said it I thought: Good end. But the movie kept going.

The bigger problem? Stories about alcoholics are not that interesting. You either continue on your downward trajectory, hit bottom and struggle back up, or die. That’s it, and that’s not enough. Is there a way to make them better? Everyone carries around something that weighs on them, some shame, but most of us are able to live with it. We function in a way alcoholics can’t. Thus there’s no public reckoning or admission. Is another group of people involved in this kind of public confession? With like-minded people? It’s like coming out of the closet but without the celebration. Maybe there should be more celebration. There’s the shame of your life being controlled and consumed, but there’s courage in the confession.

Monday November 19, 2012

Movie Review: Chasing Ice (2012)

WARNING: IT’S THE END OF THE WORLD AS WE KNOW IT, AND FOX-NEWS FEELS FINE (SPOILERS)

The great unasked question in the climate-change debate is at what point in the near-future do we string up Sean Hannity, Rush Limbaugh, and all of the other global-warming deniers from what’s left of the tallest tree? At what point will all of us, and not just scientists, know, with every fiber of our being, that the carbon emissions mankind has been adding to the atmosphere over the last 150 years is creating a greenhouse effect that is in fact, and not in theory, warming the planet, melting the glaciers, rising sea levels, and creating weather-related havoc around the globe? Before it’s too late? After it’s too late? And if the latter, how will we view those who have denied all along that it was ever occurring?

Last week, these same guys kept denying the poll numbers of statisticians like Nate Silver until Barack Obama, their bete noir both figuratively and literally, was reelected president of the United States. Silver has a book out called “The Signal and the Noise.” It’s about polls and poll numbers but the title could be about the greenhouse effect and global warming. For decades scientists have been listening to the signal and climate-change deniers have been providing the noise, but the question no one asks these guys, the Hannitys and Limbaughs, is this: If you’re wrong, and if we move too late, how will you not be viewed as the greatest villains in human history?

‘The story is in the ice somehow’

Forgive the screed but the other night I watched “Chasing Ice,” a documentary by Jeff Orlowski about National Geographic photographer James Balog, who, with a young, international team, has spent the last five years documenting, via time-lapse photography, the melting of glaciers in Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and Montana. This melting is speeding up. What took 100 years in the 20th century is taking 8-10 in the 21st. They also record, through luck or patience, the “calving” of huge chunks of glaciers. The first time we see it, early in the film, we don’t quite get what we’re watching. The glacier is rumbling and shifting, almost as if it’s alive, as if it’s rousing itself, but in what direction? Then suddenly we understand. A monumental slab of ice breaks away, shifting forward at the bottom, and falling backward. It almost looks like it’s lying down for a nap. Then it just disappears. The last such slab we see disappearing in this manner is the size of Manhattan.

Forgive the screed but the other night I watched “Chasing Ice,” a documentary by Jeff Orlowski about National Geographic photographer James Balog, who, with a young, international team, has spent the last five years documenting, via time-lapse photography, the melting of glaciers in Iceland, Greenland, Alaska and Montana. This melting is speeding up. What took 100 years in the 20th century is taking 8-10 in the 21st. They also record, through luck or patience, the “calving” of huge chunks of glaciers. The first time we see it, early in the film, we don’t quite get what we’re watching. The glacier is rumbling and shifting, almost as if it’s alive, as if it’s rousing itself, but in what direction? Then suddenly we understand. A monumental slab of ice breaks away, shifting forward at the bottom, and falling backward. It almost looks like it’s lying down for a nap. Then it just disappears. The last such slab we see disappearing in this manner is the size of Manhattan.

Balog began life as a scientist but didn’t like the fussy calculations, the stultifying lab-ness of it all, and at the age of 25 reinvented himself as a nature photographer. He didn’t know anything about photography, but, he says, “Youthful brashness can take you a long way.” He was particularly interested in how humans and nature intersected. For a time he focused on endangered wildlife. He liked taking shots at night for its absence of sheltering sky. The vastness of the night sky reminds us of what we are and where we are and what we’re on. It reminds us of the fragility of our existence.

He began as a climate-change skeptic. He couldn’t see how humans, despite their number, could have an impact on something as vast as the world. But he became interested in ice—in photographing it, in the beauty of it—and came to the story that way. “The story is in the ice somehow,” he says in the doc.

He was visiting one glacier, I believe the Solheim Glacier in Iceland, and noticed how much it had receded since the last time he was there: 100 feet per year, he estimated. That’s how he got the idea for the time-lapse photography. He created an organization, the Extreme Ice Survey (EIS), and he and his team set up 25 cameras, in hostile conditions, in March 2007. Six months later, in October, they returned to find … nothing. Some cameras were buried or damaged. Batteries exploded. There’s talk about voltage regulators. At one camera, Balog, who seems fairly even-keeled up to this point, lets loose with a burst of swearing. At another he begins to cry. “If I don’t have pictures,” he says, “I don’t have anything.”

Like watching La Sagrada Familia melt

I saw the doc with friends and some in the group, particularly the women, were put off by Balog. They felt the doc was too much about him when it should have been about it. They thought he took too many unnecessary risks for photographs that don’t have anything to do with global warming. For a time in the doc, the focus even becomes his knee. He’s had two surgeries on it, gets another, is told he can’t hike anymore. Yet there he is back in Greenland and Iceland and Alaska, traipsing through the snow to his cameras, and rappelling down ravines for that perfect shot. Until he can’t anymore. All of which is gloriously beside-the-point. If we’re talking about the end of the world as we know it, what’s James Balog’s knee in this equation? Nothing. The knee is only there for false drama. It doesn’t matter who goes to the cameras, as long as that evidence is got. If we have pictures, we have everything.

And we have pictures. We know we will. Otherwise why are we sitting in a theater watching this thing? The documentary wouldn’t have been distributed without them.

When we finally see the time-lapse photographs of the glaciers melting, it’s horrifying. It’s like watching beauty and grandeur melt away. One feels sick to one’s stomach. One wonders why it isn’t on the news and in the newspapers and on the web. But of course it is. It’s just not central to the news and the newspapers and the web. It’s not trending.

Global warming has always had trouble as a cause because it’s a completely abstract phenomenon. Every few months we’ll get a natural disaster, which may or may not be attributed to climate change, but that’s about it. It’s a slow process, whose ends are unknown, which we may or may not be causing. What Balog does is provide specific evidence. He makes it real. This is what’s being lost. These glaciers. This beauty. It’s like watching the Louvre and La Sagrada Familia and the Great Wall of China melting because of something we did, and do, and don’t care enough to stop.

‘We don’t have time’

Here’s what I’ve never understood about climate-change deniers. Global warming came to us as a theory in the 1970s, or maybe as early as the 1950s, when scientists realized we were adding carbon to the atmosphere and wondered what that might do. From a New York Times editorial in 1982:

The greenhouse theory holds that carbon dioxide, the waste gas released by burning coal, oil and gas, does for the planet what glass does for a greenhouse - lets the sun's warmth in but not back out again. Until the industrial revolution, excess CO2 was absorbed in the oceans. Now the gas is accumulating rapidly in the atmosphere. The climatologists predict that present levels of CO2 will double in the next 50 to 70 years, raising global surface temperatures an average of three degrees.

This was the hypothesis but there was no evidence to back it up. In the above editorial, called “Waiting for the Greenhouse Effect,” the Times’ editorial board wrote, “There is no cause for panic, but there are plenty of reasons for prudence.” They wrote, “Until there is indubitable proof of a global warming caused by CO2, the greenhouse effect must remain a hypothesis.”

Now we have evidence that the planet is warming, but there’s still a contingent of denier who says, “Yes, but…” Yes, but the planet’s temperature has always fluctuated. Yes, but there’s no evidence that this warming is the result of increased C02 in the atmosphere. It’s like a game in which the rules keep changing. You tell us A and we’ll ask for B, and when B arrives, decades later, we’ll ask for C. “We’ll be arguing about this for centuries,” one of the talking heads in the doc says, citing our arguments about evolution. “We don’t have time,” he says.

For all its false drama (Balog’s knee, etc.), “Chasing Ice” is a worthy doc and worth seeing on the big screen. For the few people who see it, it will, for a moment anyway, move the issue of global warming into a more central part of their psyche, which is, at the least, what we need. Just as all of us have contributed to the problem, bit by bit, all of us must contribute to the solution, bit by bit. The first step is interest.

Monday November 12, 2012

Movie Review: Skyfall (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Was I the only one who was bored by this? Who thought the slow bits weren’t intellectually engaging enough and the fast bits weren’t fun enough? We get the usual whiz-bang chase sequences in exotic locales around the world (and London and Scotland), and feints at soul searching (without much soul or searching), but it’s hardly fun. And what’s the point of being James Bond if there’s no fun in it?

Craig’s Bond has turned into a bore. He’s a drag. He has no twinkle in the eye, just a long, slow smolder. He lives in a post-9/11 world where he’s always on guard. He stands there, in his too-tight suit, ready to pop. In this movie he’s offered a new way of looking at the world and doesn’t take it. One gets the feeling he doesn’t have the imagination to take it. Or see it.

Yes, the pre-title motorcycle chase scene over the rooftops of Istanbul is glorious. Yes, the photography, particularly of the Scottish countryside, is beautiful. Yes, director Sam Mendes (“American Beauty”), and writers Neal Purvis, Robert Wade and John Logan, give us one of the great villain introductions: the long, still shot of Silva (Javier Bardem) coming down the elevator and into frame as he tells his tale of a giant hole of rats eating each other until only two survive; and these two rats, who now have a taste for rat, are set free because they will keep the island free of other rats. It’s a horrific tale that resonates. Silva is speaking of himself and Bond. He obviously feels a kinship with Bond. He’s selling himself short.

Yes, the pre-title motorcycle chase scene over the rooftops of Istanbul is glorious. Yes, the photography, particularly of the Scottish countryside, is beautiful. Yes, director Sam Mendes (“American Beauty”), and writers Neal Purvis, Robert Wade and John Logan, give us one of the great villain introductions: the long, still shot of Silva (Javier Bardem) coming down the elevator and into frame as he tells his tale of a giant hole of rats eating each other until only two survive; and these two rats, who now have a taste for rat, are set free because they will keep the island free of other rats. It’s a horrific tale that resonates. Silva is speaking of himself and Bond. He obviously feels a kinship with Bond. He’s selling himself short.

M stands for Micromanager

Here’s the description of the movie on IMDb.com:

Bond's loyalty to M (Judi Dench) is tested as her past comes back to haunt her.

I would say it’s not tested enough. M, let’s face it, is a lousy boss. She’s a micromanager. Here are some of the decisions she makes during the course of the film:

- During the pre-title sequence, M tells Bond to leave behind an injured MI6 agent, Ronson (Bill Buckhurst), knowing Ronson will die, to pursue Patrice (Ola Rapace, Noomi’s ex), who has a disc with every undercover and embedded agent on it. You get a flash of disagreement from Bond here but I’m with M. The disc is more important. The bigger question is who created the disc in the first place? Hey, let’s put all of our secrets in one place, where they’ll always be safe and no one will ever find them.

- M continues to bark orders throughout the high-speed pursuit. She then tells Eve (Naomie Harris), a relatively new agent, to shoot Patrice as he fights with Bond atop a speeding train on a trestle high above what I assume is the Black Sea. Eve is worried she’ll shoot Bond but M orders her to “take the shot” anyway. Meaning M puts more trust in a new agent than in her best agent. Not smart.

- When the MI6 network is hacked, and its headquarters bombed, she moves the agency underground, into caverns left over from … is it the Blitz? But this plays right into Silva’s hands.

- When Bond returns from the dead, and from a self-imposed exile, she clears him for duty even though he fails every test. He’s not psychologically ready. He’s not physically ready. He can’t shoot straight. But what the hell. Apparently she doesn’t have anyone else.

We also learn of the horrible decision she made that led to the present circumstances.

Bond = Batman; Silva = the Joker

Silva, you see, is former MI6. Years back, during the Cold War, M traded him for six agents. Were there extenuating circumstances? Did she just like the numbers? I forget. Silva was tortured but divulged nothing. He tried to kill himself with a cyanide capsule but didn’t die. The cyanide ate away at his insides and turned him half-insane. He stayed alive for revenge. On M. So all of this, the entire movie, is about M. MI6 isn’t saving the world from bad guys anymore; they’re eating their own. The chickens have come home to roost.

Bond has his own issues with M. He didn’t like leaving Ronson behind and he didn’t appreciate M’s “Take the shot” directive. M didn’t trust him to finish the job and it nearly finished him. “Nearly.” It should have finished him. He’s shot twice and falls hundreds of feet into the Black Sea. M and MI6 actually think he’s dead. We know he’s not because it’s the beginning of the movie and he’s James Bond. He’s our plaything. We can drop him from the moon and he’ll survive.

So what does James Bond do, being thought dead?This may be the most disappointing part of the movie for me. He sulks. He hangs out on a tropical beach, has rough sex with a local beauty, plays rough drinking games with scorpions, and loses his edge. He only returns when he hears of the terrorist attack on MI6. It gives you an idea what he’ll be like in retirement. A drag.

At this point the question of the movie becomes: Can Bond regain his edge? He’s weaker now. His hand shakes when he shoots. Losing this, he loses everything. Until he gets it back, of course. Which he does later in the film. We knew he would. We can drop him from the moon, remember.

Bond could be Silva. That’s how Silva sees it anyway. But Bond couldn’t be Silva because Bond isn’t smart enough. Silva is not only a trained MI6 agent, in the Bond mold, but he outwits the new Q (Ben Whishaw). Even when Silva’s captured, halfway through the film, he’s not really captured. He’s in a glass booth in the middle of a guarded room, like Hannibal Lector in “Silence of the Lambs,” but we know he’ll escape. Hell, he wanted to be captured. It was part of his master plan. It took me a moment to realize why this scenario—the villain, incarcerated, holding all the cards—echoed. It’s the Joker in “The Dark Knight.” He too felt an affinity with the hero, and the hero, Batman, was too dumb and humorless to see it. The dynamic is the same and it’s dull. It’s dull because the hero is dull and the villain has all the fun. Used to be the reverse for Bond. Used to be the villain humorlessly stroked cats while Bond stroked other things.

The real Bond girl

Speaking of: Where are the girls? All the movie’s pre-publicity trumpeted Bérénice Marlohe as Sévérine, but she’s killed halfway through the movie. The tropical, rough-sex beauty lasts about five seconds. There’s a fling with Eve, discreetly implied with old-fashioned fireworks, but by the end she’s a pal. By the end she’s Moneypenny. Literally.

No, the Bond girl in this movie is M. She’s the girl being fought over by hero and villain. Near the end, during the assault on Skyfall, the home in Scotland where Bond grew up and was orphaned, she’s injured and in pain, her hand is red with blood, but I felt nothing for her. Are we supposed to have sympathy? I think the filmmakers want us to. But all of this is because of her. The chickens are coming home to roost on her. There should be soul searching throughout London, and Great Britain, and the world. There isn’t. The enemy is us but we either don’t realize it or don’t care.

M dies but we get a new M (Ralph Fiennes). Bond could die but we’d just get a new Bond. We will get a new Bond, eventually, world without end. When we do, a request. Please make him a little less superseriously American, like Batman and Ethan Hunt and Jason Bourne, and a little more British. Because: Please, he’s British.

Saturday November 03, 2012

Movie Review: Searching for Sugar Man (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Searching for Sugar Man” is a good documentary about a great story.

In the 1970s in South Africa, so the story goes, there were three albums in every white, liberal (read: anti-Apartheid) home: “Abbey Road” by the Beatles; “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon and Garfunkel; and “Cold Fact” by Rodriguez. Everyone listened to Rodriguez. “He was the soundtrack to our lives,” says record-shop owner Steve Segerman, known to his friends as “Sugarman” after Rodriguez’s signature song. It just took awhile for South Africans to realize that they were the only ones listening. It took them awhile to realize that while everyone knew the Beatles, nobody anywhere knew anything about Rodriguez.

Legends about the man grew. Creation stories were perpetuated. Apparently an American girl with a South African boyfriend brought the first Rodriguez cassette tape into the country in the early 1970s. End times were debated. Apparently in an early 1970s concert he’d poured gasoline on himself and lit himself on fire. No no, he’d greeted the indifference of a tepid crowd by putting a gun to his head and blowing his brains out.

Searching for Rodriguez

Decades later, in 1996, Segerman wrote the CD liner notes to Rodriguez’s second album, 1971’s “Coming from Reality,” and, after owning up to the complete lack of information about the man, asked, “Any musicologist detectives out there?” There was: journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, who had his own list of stories to pursue, the fourth of which was: How Rodriguez died.

Decades later, in 1996, Segerman wrote the CD liner notes to Rodriguez’s second album, 1971’s “Coming from Reality,” and, after owning up to the complete lack of information about the man, asked, “Any musicologist detectives out there?” There was: journalist Craig Bartholomew-Strydom, who had his own list of stories to pursue, the fourth of which was: How Rodriguez died.

This is what he had to go on: a dead record label; a few grainy photos; lyrics. They assumed Rodriguez was American but didn’t know which city. “Inner City Blues” contains the line, “Going down a dusty Georgian side road.” So maybe the South? “Can’t Get Away” referenced being born “in the shadow of the tallest building.” So maybe New York? Bartholomew-Strydom follows the money, like Woodward and Bernstein, but it dead-ends in southern California.

He was about to give up when he honed in on another line from “Inner City Blues”:

Met a girl from Dearborn, early six o'clock this morn

The sad thing isn’t that Bartholomew-Strydom had to look up Dearborn in an atlas when almost any American could have told him it’s in Michigan; the sad thing is that that the documentary has already told us that Rodriguez is in Michigan. Early on, we hear interviews with his Detroit record producers, who lament what happened to him. We talk with people who knew him from the streets of Detroit. They say he was kind of a wandering mystic: a cross between a poet, a shaman and a hobo.

So why does Malik Bendjelloul begin his doc this way? It leaves the audience in the awkward position of waiting for its heroes, Segerman and Bartholomew-Strydom, to come up to speed.

Maybe Bendjelloul begins this way because the lamentations of colleagues reinforce the notion that Rodriguez is dead. Because that’s the big reveal halfway through the doc: He’s not dead. He’s alive. He’s been working construction and renovation in Detroit never knowing he’d become a music legend halfway around the world.

For South Africa, it’s as if Elvis has turned up alive. Most refuse to believe it. Most think it’s a hoax. Because how can Elvis and Jim Morrison and John Lennon still be alive? The world doesn’t work that way. It doesn’t give us that gift.

In subsequent interviews with the documentarian, Rodriguez, born Sixto, reminds me of artistic types I’ve known who have an ethereal matter-of-factness about them. He’s not there but amazingly present. He seems disconnected but connected to something bigger. Asked if he enjoys construction work, he says, “It keeps the blood circulating.” Asked if he knows that in South Africa he’s bigger than Elvis or the Beatles, he replies, “I don’t know how to respond to that.”

The rest of the doc is, in a sense, recognition, at long last recognition, as well as reunion, or, more accurately, union, since he and South Africa have never known each other. In 1998, he travels there with his daughters for a concert. At the airport, limos pull up and the Rodriguezes stand aside for the VIPs before realizing they are the VIPs. They expect small venues and play to rapt, screaming crowds in sold-out arenas. He goes from being a loopy, wandering guy who does construction (in America) to being a music legend (in South Africa). But he stays in America. He keeps working construction. He keeps the blood circulating.

Searching for why

That’s the story, and it’s a great story, a powerful story, a story that couldn’t exist today. South Africa needed to be isolated from the rest of the world, via Apartheid, and the world needed to be not-yet-connected, via the Internet, for the story to work: for a legend to grow in isolation.

But here’s what the doc doesn’t answer:

- What happened to all the money South Africans spent on Rodriguez’s albums? He never saw a cent of it.

- Why did Rodriguez catch on in South Africa? Some of his lyrics are mentioned, particularly “I wonder/How many times you had sex” as an eye-opening notion. Yet South Africa did have the Beatles. They had the Stones. Weren’t their eyes already open?

- Why didn’t Rodriguez catch on in black South Africa? A consequence of Apartheid? A consequence of his music?

- Why did he never catch on in the States?

This last one is the main one for me. The doc, focusing on South Africans, and created by a Swede, isn’t curious enough about the lack of curiosity in America about Rodriguez. I’ve been listening to the soundtrack for a solid month now and love it. It’s kept me going through the ups and downs of the 2012 presidential election. It feels more relevant than most contemporary music.

At times Rodriguez comes off like a soulful Bob Dylan, and, in 1970, that should’ve worked in his favor. That’s what everyone was looking for. John Prine, Steve Forbert, Bruce Springsteen: they were all new Bob Dylans. Rodriguez is so obscure he’s not even mentioned in Loudon Wainwright’s song, “New Bob Dylans.”

OK, let me admit that, yes, there’s no better lyricist than Dylan. He’s at another level, and Rodriguez, while good, is several levels below. But Rodriguez has his moments. The awfulness of war and the thanklessness of medals has been batted about by artists for a century. In Dylan’s “John Brown,” it’s the protagonist’s mother who urges her son off to war to get medals. There, he realizes he’s a puppet in a play and when he returns, injured, he tells her so. This is the last stanza:

When he turned away to go, his mother acting slow,

As she saw that metal brace that helped him stand.

But as they turned to leave, he pulled his mother close,

And he dropped his medals down into her hand.

Rodriguez’s take, from “Cause,” is also about mothers and sons, but feels truer and more poignant:

Oh but they’ll play those token games

On Willie Thompson

And give a medal to replace the son

Of Mrs. Annie Johnson

I keep thinking of these lines, too, from “Crucify Your Mind.” Any artist does. Any person does:

And you claim you got something going

Something you call “unique”

Thirty years later, Rodriguez still sounds vibrant and true. In “Searching for Sugar Man,” the people who knew, his record producers, still rack their brains about why he didn’t catch on. Should have I added more strings here? Less there?

But at one point, someone, I forget who, mentions his name: Rodriguez. They wonder if that’s the issue. They wonder if people dismissed him as Latin music. There’s no way to measure this, of course, or prove such a negative, but that’s my bet. I bet Americans thought that if they listened to someone called “Rodriguez” they would get Jose Feliciano, so they didn’t bother. But halfway around the world, people with less options had more open ears.

Dues

To me, that’s the great irony of the story of Rodriguez that “Searching for Sugar Man” doesn’t underline enough. A kind of veiled racism doomed Rodriguez in his home country; but talent and circumstances allowed him to prosper in a country that had the one of the most racist governments, and one of the most segregated societies, in the world.

From “Cause”:

Cause they told me everyone’s got to pay their dues

And I explained that I had overpaid them

Indeed. But the ending is happy, for both Rodriguez and South Africa. And for us.

Wednesday October 31, 2012

Movie Review: Cloud Atlas (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Every Hollywood movie believes in true love but only “Cloud Atlas” posits an explanation: reincarnation. We’re simply meeting someone we already knew in a previous life. The movie suggests a continuity from life to life, and an existential moral authority in which justice is meted out in this life or the next.

My thought throughout: Isn’t it pretty to think so?

Unconventional Storytelling

Admittedly “Cloud Atlas” is ambitious and unconventional in its storytelling. It gives us six stories from six eras, with the same actors playing different roles in different eras. They, it is suggested, are the reincarnated souls. Thus:

- In the Pacific Islands in 1849, Adam Ewing (Jim Sturgess) is trying to get home to San Francisco and his wife, Tilda (Doona Bae), but doesn’t know he’s slowly being poisoned by his friend, Dr. Henry Goose (Tom Hanks).

- In 1936, Robert Frobisher (Ben Whishaw), leaves his lover, Rufus Sixsmith (James D’Arcy), to become assistant to one of the world’s great composers, Vyvaan Ayrs (Jim Broadbent), only to have his ideas stolen by the great man.

- In 1973, journalist Luisa Rey (Halle Berry) investigates a nuclear power plant run by Lloyd Hooks (Hugh Grant), but all of her sources, including an aged Rufus Sixsmith (still D’Arcy) and Isaac Sachs (Hanks), wind up dead. Is she the next target?

- In 2012, a publisher, Timothy Cavendish (Broadbent), owes royalties to a gangster-novelist, Dermot Hoggins (Hanks), so his brother (Grant) agrees to hide him in a hotel; but the place turns out to be an old folks home run military-style.

- In Neo Seoul in 2144, Sonmi-451 (Doona Bae), a replicant waitron, born and bred for the purpose of serving the customer, is helped by a pureblood, Hae-Joo Chang (Sturgess), to ascend to greater knowledge and thus transform the world.

- In a post-apocalyptic future, “106 winters after the fall,” a superstitious islander, Zachry (Hanks), aids one of the last remnants of our technologically advanced civilization, Meronym (Berry) up a mountain peak in search of Cloud Atlas, an outpost and communication station, where she can contact humans living in space. For what purpose I never really understood. To make things better, I suppose.

Writer-directors Andy and Lana Wachowski (“The Matrix”), and Tom Tykwer (“Run, Lola, Run”), intercut these stories like an MTV video.  They even offer an early, meta explanation for their method. As Cavendish writes his comic tale of escape, he talks up his general distaste for flashbacks and flashforwards but considers them necessary evils. He promises, “There’s a method to this madness.”

They even offer an early, meta explanation for their method. As Cavendish writes his comic tale of escape, he talks up his general distaste for flashbacks and flashforwards but considers them necessary evils. He promises, “There’s a method to this madness.”

I can think of only one flashback in Cavendish’s tale (to his true love, of course), so the line is meant more for us than Cavendish’s imaginary readers. I found it either too cute or unnecessary handholding. I wasn’t confused by the cross-cutting. I was sadly unconfused. I got it all too quickly.

Each era leaves something behind: a story for the next generation. So the goddess worshipped in the far-flung future is Sonmi-451, whose escape was inspired, in part, by an old digital/film version of the memoirs of Cavendish, who publishes, or stupidly rejects (I forget which), a novel based upon the adventures of Luisa Ray, who reads the 1930s love letters between Sixsmith and Frobisher, the latter of whom, while collaborating on his Cloud Atlas Symphony, reads “The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing.” We are bound to each other by our stories.

But this is the best, most poetic way to describe the movie’s philosophy. It’s what Sonmi-451 says to the unseen masses of her time:

Our lives are not our own. From womb to tomb, we are bound to others, past and present. And by each crime, and every kindness, we birth our future.

Conventional stories

Sometimes this future is birthed in another lifetime. It’s karma. Broadbent’s character traps a man in one lifetime only to be trapped himself in another. Hanks’ character is corrupt first-worlder amid the island natives in 1849, then island native in a far-off future dealing with first-worlder Halle Berry (the incorruptible). When Berry and Hanks meet in 1973, he falls for her (easy to do) because he senses he already knows her (though, chronologically, their paths have yet to cross). When Berry and Whishaw, the proprietor of a 1970s record/head shop, listen, entranced, to a very rare 1930s recording of the “Cloud Atlas Symphony,” both feel they’ve heard it before. They have: he as composer, she as wife of corrupt collaborator.

More often, though, the future, and the karma, is birthed within one’s own lifetime. The kindness Ewing shows the escaped slave Autua (David Gyasi) is returned to him when Autua saves him from the machinations of Dr. Henry Goose. The kindness Cavendish and the others show by returning to save Mr. Meeks (Robert Fyfe) is returned to them when Meeks, finding his voice in a pub, rallies football hooligans to save them from Big Nurse (Hugo Weaving). Zachry twice saves Meronym’s life, despite a voodooish demon, Old Georgie (Weaving), whispering in his ear; and in the end, at the last moment, when all hope seems lost, she returns to save him and his daughter from marauding cannibals.

In fact, every story but one (maybe two) has a happy, Hollywood ending. Ewing, saved, returns to San Francisco, stands up to his father-in-law (Weaving), and becomes an abolitionist. Luisa Ray publishes her scoop about oil companies conspiring to create a nuclear disaster. Cavendish escapes the old folks’ home and is reunited with his true love (Susan Sarandon). Zachry and Meronym become husband and wife and perpetuate the species with children and grandchildren, to whom Zachry tells his tales around a campfire.

The two less-than-happy endings? In 2144, Sonmi-451 discovers that replicants, rather than “ascending” to a higher place, are killed, skinned, and served as food to the purebloods. “They feed us to us,” she says, stunned. This echoes similar sentiments in other eras. “The weak are meat and the strong do eat,” says Dr. Goose as he attempts to kill a weakened Ewing. “Soylent Green is people!” Cavendish shouts during his first failed attempt at escape. Plus the cannibals of the post-apocalyptic future. This fate awaits Sonmi-451, too. But first she gets word out to the masses. She changes the world. It would be more poignant, however, if we understood why Hae-Joo Chang saw her as “The One.” What is it with the Wachowskis and “The One” anyway? Can’t they get off that fucking horse? Can’t Hollywood? Can’t … all of us?

The other sad ending is from the 1930s, when Frobisher, the talented gay guy, for no good reason, kills himself. Someone alert Vito Russo.

But each story mostly builds toward happy endings; and the movie leaves us in the far-off future with humanity returned to its natural state: telling stories around campfires.

Hollywood ending

“Cloud Atlas” is, again, ambitious, and often beautiful. I think of Tykwer’s shots of Luisa Ray going over the bridge and into the water, then ascending. I was rarely bored. The nearly three-hour runtime went by like that. And a lot of the words, which come from David Mitchell’s novel, are just glorious.

But for all its unconventionality, each story, by itself, is utterly conventional, as is the connective tissue between the stories. “Cloud Atlas” takes our most unknowable questions, about life and love, and makes the answers obvious. In this way, it’s like almost every Hollywood movie ever made.

Monday October 15, 2012

Movie Review: The Five-Year Engagement (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

When did I give up on this movie? I guess about halfway in. That scene where Tom Solomon (Jason Segel), who has sacrificed a rising career as a sous chef in San Francisco to follow his fiancée, Violet Barnes (Emily Blunt), to Michigan (where she is a Ph.D. student in social psychology), is babysitting Violet's 3-year-old niece and takes his eye off her for a second to watch a cat video on YouTube. The girl goes missing. She winds up in the kitchen behind Tom’s cross bow. (“Cross bows don’t clean themselves,” he explains to Violet as to why it’s on the kitchen table.) Then the girl shoots Violet in the leg. Then her parents return, and we get anger and recrimination and blame. And a close-up of the wound.

It just seemed a bit much.

By this point we’re seeing how low Tom can sink. In Ann Arbor, instead of running a foodie joint by the bay, he’s making sandwiches in a local deli and hanging with other, neutered faculty husbands like Bill (Chris Parnell), who knits sweaters and hunts deer. The knitting is for something to do. The hunting is, one assumes, to replenish his disappearing manhood. Tom finds himself following suit, first with a rifle and then with a cross bow. He begins to display flowing, Civil-War-era facial hair. He wears the draping sweaters Bill knits. He begins to make mead from honey. He serves his wilderness fare in fur-covered mugs.

By this point we’re seeing how low Tom can sink. In Ann Arbor, instead of running a foodie joint by the bay, he’s making sandwiches in a local deli and hanging with other, neutered faculty husbands like Bill (Chris Parnell), who knits sweaters and hunts deer. The knitting is for something to do. The hunting is, one assumes, to replenish his disappearing manhood. Tom finds himself following suit, first with a rifle and then with a cross bow. He begins to display flowing, Civil-War-era facial hair. He wears the draping sweaters Bill knits. He begins to make mead from honey. He serves his wilderness fare in fur-covered mugs.

The niece is the child of his goofball friend, Alex (Chris Pratt, Scott Hatteberg of “Moneyball”), and her sharp-tongued sister, Suzie (Alison Brie, Pete Campbell’s wife from “Mad Men”), who met at Tom and Violet’s engagement party and then quickly zipped past them in making a life together. She got pregnant, they got married (with a beautiful ceremony), had the kid, then another. When Tom followed Violet to Michigan, Alex, the screw-up, got the job running the clam bar that was meant for Tom.

Violet, meanwhile, is enjoying her work at the University of Michigan, but her fellow grad students, Vaneetha, Ming and Doug (Mindy Kaling, Randall Park and Kevin Hart), are all one-note sitcom characters, while their advisor, Winton Childs (Rhys Ifans), is obviously making a play for Violet. We wait for it to happen. It does. We wait for the eventual breakup. It occurs. We wait through their new, awkward relationships until they get back together and get married. They do. At the end. Two hours into the movie.

Two hours? For a rom-com? A clue right there.

I liked “The Five-Year Engagement” at the beginning. It felt true and slightly original. Segel and Blunt have great chemistry and are generally sweet together. Plus there are great laugh-out-loud lines. When Violet talks about hurrying up the wedding plans, her sister tells her, “Hey, it’s your wedding. You only get a few of these.” When they worry what the relatives will say when they delay the nuptials, Tom declares, “They’ll live.” Cut to: a funeral.

But there’s too much. They keep pushing the envelope unnecessarily. One of Violet’s fellow grad students is obsessed with masturbation; another with blood and chicken feathers. When Tom gets angry at Vi, he winds up with a crazy girl who wants food-fight sex … or something. He leaves that encounter half-naked, winds up sleeping half-naked outside in winter, and loses a toe to frostbite. Funny. When he opens a foodie taco truck back in San Francisco, to raves, the guy waiting in line can’t just tell him how much he likes his tacos; he has to ask him for a hug. Grandparents have to keep dying, her father has to keep marrying younger Asian women, his mother has to talk to him about her vaginal reconstruction surgery. After a while, it feels like everyone is doing standup rather than serving the needs of the story.

Some envelopes aren’t meant to be pushed. Some bits need a little less commitment.

Friday October 12, 2012

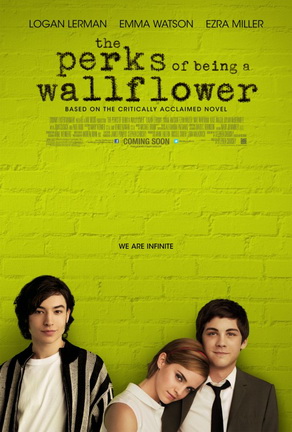

Movie Review: The Perks of Being a Wallflower (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Stephen Chbosky’s “The Perks of Being a Wallflower” is a surprisingly good film about the first awkward steps of high school and the even more first awkward steps of love. I liked it, and was moved, even though I’m about to turn 50. I felt long-ago pangs and longings. I felt this despite being painfully aware of the film’s central lie: that the perks of being a wallflower generally don’t include Emma Watson.

Off the wall