Movie Reviews - 2012 posts

Wednesday March 27, 2013

Movie Review: On the Road (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Near the beginning of “On the Road,” the adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s seminal 1957 novel by screenwriter Jose Rivera and director Walter Salles, Sal Paradise (Sam Riley) is saying good-bye to friends Carlo Marx (Tom Sturridge) and Dean Moriarity (Garrett Hedlund), who are leaving New York for Denver, and the three gather in a photobooth for a picture. Back then, apparently, you only got one photo, not four, so Dean takes out a razor blade and cuts the picture in half. Meaning he cuts Sal in half. Then he gives Sal the half with his picture on it (plus half of Sal) and keeps the half with Carlo (plus half of Sal).

You could say this represents the great bifurcation of Sal Paradise, who is trapped between the writing life, as represented by Carlo (read: Allen Ginsberg), and the wild, mad life on the road, as represented by Dean (Neal Cassady), and only much later, near the end of the movie, when the two halves are brought together again, does Sal see a way out of his dilemma. He joins the Dean and Carlo halves of his soul by taping together many hundreds of 8x11 pieces of paper until he has a whole roll; then he just cuts loose on the keyboard. In mad-to-live, mad-to-talk bursts, he reproduces their life on the road on paper. Which is supposedly how Kerouac created his masterpiece.

I was never a fan, by the way.

The white boy looks at the black boy looking at the white boy

I read “On the Road” for the first and only time in my early 20s, which is when you’re supposed to read it and fall in love with it, but I didn’t. I was a careful kid. Too careful, really, but I knew what I liked. I liked Salinger, Roth, Doctorow, and Irving, who wrote beautifully about things that mattered. Kerouac, it seemed to me, didn’t write beautifully about things that didn’t matter. The adventures he described were episodic and dull. His voice felt like someone trying to push a Volkswagen up to 150 mph. I found the characters Sal and Dean and Carlo, based upon Kerouac and his friends, frenetic and pretentious.

I read “On the Road” for the first and only time in my early 20s, which is when you’re supposed to read it and fall in love with it, but I didn’t. I was a careful kid. Too careful, really, but I knew what I liked. I liked Salinger, Roth, Doctorow, and Irving, who wrote beautifully about things that mattered. Kerouac, it seemed to me, didn’t write beautifully about things that didn’t matter. The adventures he described were episodic and dull. His voice felt like someone trying to push a Volkswagen up to 150 mph. I found the characters Sal and Dean and Carlo, based upon Kerouac and his friends, frenetic and pretentious.

I wasn’t the only one.

In the essay, “The Black Boy Looks at the White Boy,” from the collection “Nobody Knows My Name,” James Baldwin takes Kerouac apart. First he quotes him at length:

At lilac evening I walked with every muscle aching among the lights of 27th and Welton in the Denver colored section, wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough life, joy, kicks, darkness, music, not enough night. I wished I were a Denver Mexican, or even a poor overworked Jap, anything but what I so drearily was, a “white man” disillusioned. All my life I had white ambitions. … I passed the dark porches of Mexican and Negro homes; soft voices were there, occasionally the dusky knee of some mysterious sensuous gal; and dark faces of the men behind rose arbors. Little children sat like sages in ancient rocking chairs.

Then he lets him have it, keying in on one of Kerouac’s favorite words:

Now, this is absolute nonsense, of course, objectively considered, and offensive nonsense at that: I would hate to be in Kerouac’s shoes if he should ever be mad enough to read this aloud from the stage of Harlem’s Apollo Theater.

Salles’ movie, however, is quite good. Yes, it’s still episodic, and, yes, it merely builds toward dissolution—toward that moment when young friends are pulled in different directions, and they give up the mad life, or the chance at the mad life, and instead of seeing jazz in sweaty Negro clubs they see it at Carnegie Hall wearing suits and ties. But then the movie pushes past all that toward creation, Sal’s creation, or recreation, his melding of the two halves of his soul so he can write it all down. I like that.

We also lose, for the most part, Kerouac’s voice. This is generally a negative for movies adapting great works of literature. Who’d want to give up Fitzgerald’s voice in “The Great Gatsby,” Nabokov’s in “Lolita,” Proust’s or Joyce’s anywhere? But with Kerouac it’s a plus. I don’t have to hear him pushing his Volkswagen up to 150. I don’t have to hear him romanticize about dusky knees and lives he knows nothing about. Salles edits him. He makes Sal seem less of an asshole.

What they do with it

Watching Salles’ movie, I got a real sense of the narrow niche, in time and place, that allowed this story to occur. At one point they hop a train and I thought, “Fifteen years earlier, they would’ve been hobos in the Depression.” They rock out to Negro jazz and scat and I thought, “Ten years later, would it be rock n’ roll? And, if so, could they see themselves on the stage in a way they don’t now? Would they form a band, ‘The Beat Generation,’ with their Top 40 hit, ‘Mad to Live, Mad to Love’?” Their story happened the way it happened because it was after the Depression and after the war, but before the country was unified by television and the Interstate Highway Act of 1956.

Was the madness here a consequence of the war? A consequence of the bomb? Sal in the novel is ex-GI but I don’t think we get much war talk in the movie. One can assume these were kids raised during great economic dislocation, who, in adolescence, were geared toward war, propagandized daily, but who suddenly found themselves at the height of their energy and strength with no World War and no Depression. The rest of the world was licking its wounds, rebuilding from the rubble, but America was fairly untouched and affluent, and what did you do with that?

This is what Dean and Sal and company do with that:

- Get high

- Go to jazz clubs

- Drive fast

- Have lots of sex with lots of partners

- Have pseudo-intellectual conversations

They’re the model for every annoying undergraduate since.

They crisscross the country. At first, it’s Sal, alone, with his thumb, and he hangs with Carlo and Dean in Denver, then continues onto California, where he hooks up with Terry (Alice Braga, niece of Sonia), who is part of a migrant-worker community there. Everyone picks cotton, gets their dismal pay, but only Sal pauses before The Man with a look on his face. He can afford to. In voiceover he tells us, “I could feel the pull from my life calling me back.” He has that option. He gets to play at being a migrant worker and then leave. The others don’t. Hence Baldwin’s anger, above.

All of the characters love Dean. He’s handsome and vibrant and sexual. He wants, wants, wants, but without consequence, and there are always consequences. He wants the freedom to flit, but flitting means abandonment. It means betrayal. He’s a con man. I like when he gets the girl for Sal, Rita (Kaniehtiio Horn), and, with Carlo, the four of them are partying and drinking and dancing, and Rita says, “Bless me, Father, for I will sin.” Then we hear moaning from the bedroom, and the camera slowly pans left, to Carlo and … wait for it … Sal, dazed on the couch, where Sal wonders aloud: Wasn’t the girl for me? But all the girls are Dean’s.

The main girl is Marylou (Kristen Stewart), who is supposed to be 16, but Stewart hardly looks it. There’s also Camille (Kirsten Dunst), Dean’s wife in San Francisco. They have a baby, another on the way, when Sal shows up and Dean asks to go out with him by asking Camille along, too, knowing she can’t. She calls him on it but off he goes. When he returns at dawn, she demands he leave. There’s a great look on her face, panic as she gets what she wants, which isn’t what she wants. She wants him to stay, to beg her to stay, but that’s not him. So he leaves her there with one baby and another on the way. How bad must you be when William Burroughs (Old Bull Lee, played by Viggo Mortensen) calls you irresponsible?

The final abandonment is of Sal, with dysentery, in Mexico.

Marylou at 81

So “On the Road,” the movie, is better than “On the Road,” the book. It actually makes all the sex and drugs and travel look pretty bleak. The cast is good, and Hedlund, he of the deep voice, is a future star.

As I was writing this, though, I kept wondering about Marylou. If she was 16 in 1947 she’d be 81 now. Does she think back on those days? Does she remember sitting between two guys in the front seat of a ’49 Hudson shooting through Arizona, all three of them naked, and jacking them both off at the same time? What smile flits across her creased face then?

That’s the distance that matters to me. That’s the road the matters. We’re all on it.

Sunday February 17, 2013

Movie Review: Tabu (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

From the first frame I felt trapped. I watched the safari adventurer standing there in his pith helmet and moustache, slouched, torpid, and looking nothing like a safari adventurer, as Africans paraded past carrying equipiment on poles, with the jungle around him, what’s supposed to be the heart of the dark continent, looking more like the sparse woods near your home, the clumps of trees and wild grass next to Minnehaha Creek in south Minneapolis, for example; and it was all so flimsy, so devoid of life, and filmed in black-and-white with an old timey aspect ratio (1:37: 1), that I merely thought one thought: “Oh no.”

I might have left right then but I was with friends, whom I’d dragged to this. I’d heard good things. Some critics put “Tabu” in their top 10 for 2012. A few made it their No. 1 movie of the year. But from the first frame I feared their idea of what’s art, or storytelling, or truth or beauty, wasn’t mine. Not close.

For the rest of the movie I hope my first impression was wrong. I hoped I’d get interested.

For the rest of the movie I hope my first impression was wrong. I hoped I’d get interested.

It wasn’t. I didn’t.

Mt. Tabu

The opening scenes are from an old movie, a story of lost love and ghosts and crocodiles on the African continent, which Pilar (Teresa Madruga) is watching in modern-day Lisbon. She’s 60s, a good, God-fearing woman living alone in an apartment. Her neighbor is Aurora (Laura Soveral), older and with a hint of faded glamour, but beginning to lose it. We get an interesting scene in a casino where Aurora talks of a dream set in Africa, with a husband with hairy arms pretending to be a monkey, and the background keeps shifting in the telling. Writer-director Miguel Gomes does more interesting things with that background than he does with anyone in the foreground for the rest of the movie.

“Tabu” is split in two parts. The first deals with a bit of Pilar’s life, including a Polish exchange student who abandons her on sight, and a would-be artist who attempts to romance her. But mostly she gets involved in the decline and fall and eventual death of Aurora. On her deathbed, Aurora gives Pilar a name, Ventura (Henrique Espírito Santo), who is the key to the second part of the story, the earlier part of the story, set in the days of Portugese colonialism in the shadow of the fictitious Mt. Tabu in Africa. He tells it to Pilar and Aurora’s live-in maid, Santa (Isabel Muñoz Cardoso), while we watch. It’s a tale of adultery and searing love. It recalls the line of narration from the pith-helmet movie that opened the film: “You can run as long as you can, and as far as you can, but you cannot escape your heart.”

I like some of this narration. I like some of the photography. But there’s no life here. The faces of the characters are as blank and deadpan as the faces of commuters on a city bus. Remember John Ford’s admonition to film the most interesting thing in the world—a human face? Gomes gives lie to this. He shows the opposite. In his hands, a human face is the least interesting thing in the world.

Mt. Brody

So why do other critics like “Tabu” so much? Here’s Richard Brody in The New Yorker:

In Gomes’s ingenious vision, the smoothed-out, tamped-down, serenely cultured solitude of the modern city, with its air of constructive purpose in tiny orbits, rests on a dormant volcano of passionate memories packed with adventurous misdeeds, both political and erotic. Filming in suave, charcoal-matte black-and-white, he frames the poignant mini-melodramas of daily life with a calmly analytical yet tenderly un-ironic eye. If today’s neurotic tensions come off as a corrective to past crimes, even a form of repentance, Gomes’s historical reconstruction of corrupted grandeur is as much a personal liberation as a form of civic therapy.

That’s some heavy lifting. Me, I need more life in my films. I need to be able to breathe. In “Tabu,” from the first frame, I felt entombed in something that wasn’t true or beautiful or worth what little time I have left in this existence.

Saturday February 09, 2013

Movie Review: Amour (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Returning from a piano concerto, Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) comments to his wife Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) about the scuff marks on the lock to their beautiful high-ceilinged Paris apartment. They’re screwdriver marks. Someone has tried to break in. He dismisses the would-be thieves as amateurs, not professionals, but for the rest of the movie this feeling of imminent invasion and theft never goes away. It always feels like someone or something is about to come through the door because something is. The movie is about the most professional thief of all. The one we can’t keep out. The one who, in the end, takes everything.

If most movies lie to us or ply us with wish-fulfillment fantasies (we are handsome, good and victorious), the movies of German writer-director Michael Haneke do the opposite: they lay bare, in the starkest way, our greatest fears: We are not safe (“Funny Games”), we are not good (“The White Ribbon”), we have no privacy (“Caché”). Plus we have no idea what’s going on (all of the above).

With “Amour,” he focuses on our greatest fear: We are going to die. And death, when it comes, won’t be easy and it won’t be pretty.

Hurts hurts hurts

The above concert, performed by Alexandre (Alexandre Tharaud), a former student of Anne’s who is now internationally acclaimed, is the first and last time we see Georges and Anne outside their apartment. The next morning during breakfast, in the midst of casual conversation, Anne suddenly stops talking and stares into space. Georges can’t get a reaction out of her. She’s upright but not there. He puts a towel to her face and neck. He returns to the bedroom to change out of his pajamas to get help.  Then he hears the water in the kitchen stop running. It’s Anne. She’s back but doesn’t remember being gone.

Then he hears the water in the kitchen stop running. It’s Anne. She’s back but doesn’t remember being gone.

We get medical terminology. Something stopping the flow of blood somewhere. People arrive, help out, including Georges and Anna’s daughter, Eva (Isabelle Huppert), and the concierge and her husband, and then workmen installing a medical bed. When we next see Anne she’s in a wheelchair. She’s having trouble moving. A stroke? Is it just her right side? Yes and yes. “Please, never take me back to the hospital,” she tells her husband. He promises. “Don’t feel guilty,” she tells him. “I don’t feel guilty,” he responds, confused.

He helps her with her physical therapy. He tells her stories about his youth. He reluctantly goes to the funeral of a friend, Pierre, but, in the reporting, criticizes the event: the eulogy was bad, the music chosen, “Yesterday” by the Beatles, was maudlin and provoked laughter from the young, the urn stood on a stand meant for a coffin. Anne doesn’t want to hear any of this. I suppose Georges is her Michael Haneke, telling her unpalatable truths. “You’re a monster sometimes,” she tells him, “but very kind.” Haneke shows us monsters. The kindness we get here is new.

Anne’s former student, Alexandre, turns up, initially full of himself, and Anne is happy to see him but he’s obviously shocked by Anne’s state. Days later, when he sends along his latest CD, the note talks of “the beautiful and sad moment” of his visit. Anne’s face closes off. During his visit, she’d requested a number, and he’d filled the room with beauty. Now she tells Georges to turn off his CD. His visit, I’m sure, was a high moment for her, and now it’s tarnished by the word “sad.” She doesn’t want pity. She wants to maintain a certain level of dignity. But time keeps slipping in and stealing things.

She wets the bed. Eva visits again, this time with her British husband, Geoff (William Shimell), and by now, Anne, bedridden, can only speak gibberish. Apparently there was a second stroke. She has to wear a diaper. She’s fed mush. Wasn’t it just a few scenes ago where she was eating dinner with her husband in the kitchen? Steak and vegetables? At that time, her world seemed narrowed but now that moment feels full of possibility. One thinks of Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Illych.” The world keeps shrinking and shrinking. Time keeps taking and taking. Anne is Georges’ whole life now. He hires one nurse, then another. The second one is incompetent, obtuse in her cruelty. She brushes Anne’s hair too hard, then forces her to look into mirrors she doesn’t want to look into. Georges fires her. She doesn’t get it. Georges explains. She refuses to see it. She calls Georges names. “You’re a mean old man,” she says. More Beatles.

George tries to feed Anne but she’s obstinate and angry. “If you don’t drink, you will die,” he says. “Do you want that?” She does. He forces water on her. She spits it out and he slaps her. Both are horrified by what they’ve become.

She moans a lot. “Money for concert,” she says at one point, remembering, no doubt, something from childhood. “Hurts, hurts, hurts,” she says more often. He returns to her bedside, pats her hand to calm her, tells her another story. She calms down. Then he grabs a pillow and against her struggles smothers her to death. It’s not just what she wants, it’s what we want, too. Make it fucking end.

What nightmares may come

We actually watch the entire movie waiting for the moment of death. In the beginning, before the concert, we see the police and concierge break down the door to her bedroom, where Anne lies, as if in state, on a bed amid flowers. Her face is slightly shrunken and the men hold handkerchiefs to their noses and open the windows. Otherwise the place is empty. As a result, throughout the film, we’re wondering how it gets to that point. Why does Georges leave her this way? And where does he go?

He drifts. After Anne’s death, he gets flowers. He prepares her. He seals up her bedroom. Pigeons often get into their apartment and he works to shoo them out but now we watch him close the window on one pigeon and trap it with a blanket. We assume the worst (it’s Haneke) but he simply strokes it beneath the blanket. He’s lonely. At least that’s how I read it.

When he leaves the apartment, at Anne’s urging, is that the moment of his own death (she returns to get him) or the moment when delusion trumps reality? Is he dead in the apartment or does he wander the street, perhaps to die there, or to be found and put in a hospital, where he’ll die, amid the tubes and the diapers and the slow closing off of the world? This is kindler, gentler Haneke (that pigeon wouldn’t have survived in “The White Ribbon”), but he still leaves us with questions. He doesn’t round off his ending. It’s as frayed as ever.

In the theater lobby afterwards, with everyone trying to exhale and live again, a woman in her sixties turned to me. “I have two words for that movie,” she said. “Assisted suicide.” I nodded, paused. “I have four words for that movie,” I said. “I need a drink.”

Neither her two words nor my four words relieved the horror. On the walk home I saw a little girl, 5 maybe, skipping in an alleyway between her parents, and wanted to yell at her. “Don’t you know what’s going to HAPPEN?!? The awful fate that awaits you!?! Yes, YOU!” Is this what it’s like being Michael Haneke? How does he sleep? What nightmares does he have? Or does he put them on the screen for the rest of us and sleep like a baby? Many people see me as a cynic, a grump, a curmudgeon before my time; but compared to Haneke I feel like the most wide-eyed Pollyanna that ever skipped the earth.

The dude’s a cold genius, but there’s little warmth and not much beauty in his vision. I think of Bill Cunningham’s line from last year’s documentary: He who seeks beauty will find it. Where is the beauty in Haneke’s vision? Where is the joy? Surely there’s joy. Once in a while?

If this is “Amour,” and I get why it is, please, Michael Haneke, don’t show us “Haine.”

Monday February 04, 2013

Movie Review: Rust and Bone (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I want the movies to stun me. I want to walk out of the theater in a daze. Hollywood didn’t help much in this regard this past year. They left it to the French to pick up the slack.

“De rouille et d’os” (“Rust and Bone”) is a beautiful film about tragic circumstances. In the hands of a lesser writer-director, it would be melodrama but Jacques Audiard (“Un Prophete”) makes poetry out of it. A bloody tooth, loosened during a fight, spins in slow motion on the pavement as if in dance. A woman whose legs have been cut off above the knee returns to the ocean, whose warm waters glisten. Later, with metal legs and cane, she walks down the steps at Marineland, where she once worked, and stands in silence before a large glass tank. She pats the glass once, twice. After a moment, a monster looms into view. An Orca. The Orca? The one who took her legs? One assumes not. One assumes that one has been killed but you never know and Audiard never says. We simply watch the whale move with her movements. It’s been trained, and she was one of its trainers. She’s confronting her past, finally, but it’s also a moment steeped in silence and mystery and beauty and forgiveness. It’s the best scene of 2012.

Being watched, getting bored

“Rust and Bone” is a tougher story to tell than Audiard’s previous film, “Un Prophete,” and not because Stéphanie (Marion Cotillard) loses her legs a half-hour in.  “Un Prophete” was about one man: Malik. The camera follows him. Easy. This is about two people, Stéphanie and Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), and for half the movie they’re not together. Audiard has to juggle their storylines. He has to bring them together, and apart, and together, in a way that feels real.

“Un Prophete” was about one man: Malik. The camera follows him. Easy. This is about two people, Stéphanie and Ali (Matthias Schoenaerts), and for half the movie they’re not together. Audiard has to juggle their storylines. He has to bring them together, and apart, and together, in a way that feels real.

They don’t meet cute. He’s a down-on-his luck Belgian boxer with a five-year-old son, Sam (Armand Verdure), who comes to stay with his sister, a cashier, in a clapboard, motel-like apartment complex in Antibes, near Nice, on the southern coast of France. We watch him scrounge for food, steal, hitchhike. He’s not the best father. He often seems lost in thought but one can’t imagine the thought. He’s mostly just there.

Through a friend of his sister’s he gets a job as a bouncer at a club, L’Annex, and later that night there’s a fracas and Ali is restraining a guy who’s causing trouble. We see a woman’s legs, supine, on the dance floor, then her bloody nose. Did the dude punch her? Aren’t there laws against that? Not against punching women in general but Marion Cotillard. That’s like digging an elbow into the Mona Lisa or taking a hammer to Michelangelo’s David.

On the drive home, she’s drunk and distant, he’s matter-of-fact and clumsy. He mentions the way she dresses. How do I dress? she asks. He fumbles a bit. He doesn’t have the word. Actually he does, and uses it with a shrug: whore. She can’t quite believe him. This pattern will repeat itself.

It’s significant, of course, that we first see her as legs. It’s significant that he stares at her legs on the ride home. It’s significant that he goes up to her place to ice his knuckles, since his knuckles will have a rendezvous with ice later in the film.

After she’s lost her legs, and after they’ve begun what they’ve begun, we’ll get a better understanding of what might have happened that night at L’Annex. She makes this admission to him:

I liked being watched. I liked turning them on. I liked getting them all worked up. But then I'd just get bored.

Past tense. She obviously misses it—and doesn’t. She obviously doesn’t particularly like the person she was—but misses it.

We get a soupçon of her life before the Marineland accident, and at the hospital we see the result before she does. We see the absence and wait uncomfortably. This has been a famous scene before, notably in “King’s Row” with Ronald Reagan. “Where’s the rest of me?” he says. It’s probably the best acting he ever did. Cotillard blows him away. She grounds an unreal scene. Her trauma is overwhelming. “What did you do with my legs?” she says over and over, on the floor, crawling, because there are no other words. There are no other words for a long time.

Do you even realize?

Would Stéphanie and Ali have gotten together without the accident? There are barriers of class and attitude between them. He’s working class, she’s middle class or higher. She’s educated, he’s not.

But he’s exactly what she needs because he’s without pretense or pity. He does what he does, wants what he wants, shrugs away the rest. She’s been holed up in a state-run apartment for months when he first visits her. He wants to go outside; she doesn’t; they do. He wants to go swimming; she doesn’t; they do. “Do you even realize?” she says when he first suggests it. Do you even realize? He doesn’t. That’s his charm. On the boardwalk, she whistles for him, like a dog, and he carries her closer to the water, and then into the water, where she’s tentative at first—she doesn’t know how well she’ll swim without the bottom half of her legs. Then she feels it. Then she knows she can do it. In the audience I worried she’d try to swim away and drown herself but Ali has no such worry. He actually dozes on the beach, and she has to whistle for him again to come get her. “Fuck, this feels good,” she says.

It would be reductive to suggest she tames and trains this beast of a man, this mixed martial-arts fighter, the way she tamed and trained whales. He’s not much of a beast, for one. He has kindnesses. He’s just a lunk. He’s generally a considerate lunk but other times not. He’s impatient with his son, non-committal with his sister. He doesn’t think of the consequences of his actions. This helps with Stéphanie, initially, because others are walking on eggshells around her and it’s the eggshells that hurt. One day she talks about not having had sex since the accident, not knowing if it even works anymore, and as they’re doing dishes he brings it up:

He: You want to fuck?

She: What?

He: To see if it still…

She: Just like that?

Just like that. I like a scene, at the gym where we trains, where he watches a woman leading others in aerobics or yoga; then the two are outside smoking cigarettes and he says a word of greeting; then they’re fucking. Just like that. This tryst causes him to be late picking up Sam at school, for which he’s admonished by an administrator. Third time in two weeks, he’s told. Do you even realize? After a mixed martial-arts victory, he and his crew, including Stéphanie, go to L’Annex, but he leaves with another girl. She goes to the bar to drown whatever she’s feeling, and a clumsy, overbearing dude tries to pick her up. Then he sees her metal legs. Then he’s on eggshells. His apology implies this: I should have pitied you instead of lusted for you. He gets a drink in the face and a bloody nose. We’ve come full circle. The next morning she lays out the rules with Ali, who chafes under rules. But she’s matter-of-fact about it:

Let’s show some manners. I mean consideration. You’ve always been so considerate to me. We continue but not like animals.

One doesn’t expect much from his fight career but he’s good. He thrives on it. After one victory he’s so pumped he needs to expend more energy and bursts out of the van for a run. Some of the best moments in the movie are the small moments: the confused pride on Stéphanie’s face when she’s nonchalantly dismissed as “his girlfriend”; the way she jerks imperceptibly when he’s taken down; the look of amused pride on her face when she takes over as his manager and deals successful with the rabble of noisy, bartering men.

Of course, to me, any moment with Marion Cotillard’s face in it is a good moment.

Just like that

Things fall apart in a way that feels aesthetically pleasing. Ali helps his manager, Martial (Bouli Lanners), who is silent, bearded and gruff, install camera equipment at stores. Not to spy on customers but workers. It’s illegal, they’re found out, photos are taken by angry employees, and Martial has to leave town to avoid prosecution. But as a result of this work, Ali’s sister gets canned for taking expired foods that have been tossed by the company. Imagine: She takes in Ali, takes care of his son, and he gets her fired. Do you even realize? There’s a scene. There’s a shotgun. He leaves. Just like that.

Is the ending hurried? Suddenly Ali is training for national tournaments in the snow, and the sister’s boyfriend brings Sam to the camp for the day. They’re skating in their shoes on an iced-over lake, and Ali turns to take a piss. Behind him we see Sam disappear through the ice. Eventually Ali runs to the hole but finds his son some distance away, trapped beneath the ice. It’s a horrific image. He begins to pound on the ice with his bare fists. Something begins to crack but we don’t think it’s the ice. “Rust and Bone” is such a tactile movie. I doubt many people in the audience breathed during this scene.

In a voiceover we’re told about bones breaking and healing but how afterwards, as Hemingway said, some are stronger in the broken places. Not the bones in the hand, though. You feel those breaks the rest of your life. So I assumed his career was over. I assumed the movie was about a swimmer who loses her legs and a mixed martial-arts fighter who loses his fists, but in the final shots he’s with Stéphanie and Sam at a Warsaw hotel before a big, international match. So that’s not it. So I suppose it’s about the pain. It’s about continuing with a pain that won’t go away. I suppose that’s why we get, as the credits roll, Sigur Rós’ “The Wolves (Act I & 2)” sounding like a benediction:

Someday my pain

Someday my pain will mark you.

Harness your blame

Harness your blame and walk through.

I left the theater in a daze. I walked and walked and didn’t want to lose the feeling the movie gave me like a gift.

Saturday January 12, 2013

Movie Review: Zero Dark Thirty (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Does it or doesn’t it?

That’s what I wanted to know last month and I couldn’t get a straight answer from the myriad critics and commentators and clowns who had seen the film. They all disagreed. Detractors called it morally reprehensible. Advocates brought up the fact that the U.S. government under Pres. George W. Bush did in fact torture people, as if that were the controversy. But this was the controversy:

Does “Zero Dark Thirty” suggest that torture led to the intel that led to Osama bin Laden?

If so, I argued, then it disagreed with the facts as we knew them.

I finally saw the film the other day, and I left the theater thinking it did something worse: it dramatized not just the efficacy of torture but its necessity. Yes, it makes torture look pretty awful, and the Americans who torture become depleted as well. But torture becomes the thing that needs to be done in order to achieve the film’s goal, which is getting Osama bin Laden. It’s how our heroes get their hands dirty, unlike those folks back in Washington, D.C., who sit behind desks. This is a conceit of many Hollywood action movies. The audience shares a knowing wink with the heroes on the screen. We’re all adults here; we know how the world works. Think of the way Pres. Lincoln bribed lame-duck congressmen to pass the 13th amendment in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.” To do good, you need to do a little bad. Except this time it’s torturing people.

I finally saw the film the other day, and I left the theater thinking it did something worse: it dramatized not just the efficacy of torture but its necessity. Yes, it makes torture look pretty awful, and the Americans who torture become depleted as well. But torture becomes the thing that needs to be done in order to achieve the film’s goal, which is getting Osama bin Laden. It’s how our heroes get their hands dirty, unlike those folks back in Washington, D.C., who sit behind desks. This is a conceit of many Hollywood action movies. The audience shares a knowing wink with the heroes on the screen. We’re all adults here; we know how the world works. Think of the way Pres. Lincoln bribed lame-duck congressmen to pass the 13th amendment in Steven Spielberg’s “Lincoln.” To do good, you need to do a little bad. Except this time it’s torturing people.

But I saw no direct link between that torture and the intel to get bin Laden.

Then I got home, read some of the commentary, particularly Glenn Greenwald’s in The Guardian, and realized I’d missed it. There is such a link. Suddenly I had sympathy for all of those critics who couldn’t give me a straight answer last month. An hour after seeing the movie, a movie in which I’d searched for this very thing, I couldn’t give myself a straight answer.

So I went to see the movie a second time.

This particular story

One wonders why screenwriter Mark Boal and director Kathryn Bigelow went with this particular story. They had so many options.

They could have made the movie about the U.S. Navy Seal team, Team Six, that actually went into Abbottabad, Pakistan, and killed bin Laden. Instead they’re the tail-end of the film and we hardly get to know them. They’re virtually interchangeable. They’re scruffy and wear fatigues and—for much of their time onscreen—night goggles. They seem like insect creatures in an alien land. We don’t see their faces. Is that the Aussie dude from “Warrior”? Or is that the other bearded guy? Or that third bearded guy? The assault on the compound is fascinating for how dull it is. Bigelow doesn’t use quick cuts or pulse-pounding music. It is not triumphant. Far from it. It’s done with a whisper, professionally, almost in real time. Back in Afghanistan, there are congratulations, and shouts of joy, but also a 10-year-long exhale. The ending, with Maya (Jessica Chastain) on the military plane being asked where she wants to go, and stopping, and tears welling up, is like the ending of “The Graduate” or “The Candidate.” What do I do now? We don’t know who we are anymore.

The movie begins with a minute of blackscreen audio from Sept. 11, 2001. We hear screams. We hear conversation between someone in the towers and a 911 operator. “I’m gonna die.” “No, ma’am, stay calm.” “It’s so hot, I’m burning up.” Then just the operator: “Can anyone hear me?” Then it’s two years later and we’re at a black ops site where old-hand Dan (Jason Clarke) and newbie Maya are torturing Anmar (Reda Kateb) to get information about the next attack.

It’s a long movie, 157 minutes, and in each segment Maya partners with a different person, or group of people, in the intelligence/military community, to get bin Laden. Maya is the driving force, the laserlike focus, but mostly it’s the others who gather the intel. Dan gets Anmar, after two years, to give up the name “Abu Ahmed,” a nom de guerre, which Maya carries with her through the years, through rumors of his death and arguments with Jessica (Jennifer Ehle, Rosemary Harris’ daughter), who thinks bribery trumps ideology, until Debbie (Jessica Collins), a newbie in the Pakistani office, finds Abu Ahmed’s real name in an old file. Maya then convinces Dan, back at Langley, to get a Kuwaiti contact to find the family, whose phone is then tapped. She convinces Larry from Ground Branch (Édgar Ramirez of “Carlos” fame) to use his limited resources to search for the son who keeps calling from phone centers near Islamabad. It’s another analyst, Jack (Harold Perrineau), who brings the news that this son, surely Abu Ahmed, has bought a cellphone, and they’re able to track its signal; and in this manner, and despite the fact that this man always calls at odd hours and on the move, they manage to get a photo of him, which their Pakistani sources use to track his movements through the city. Which is how we wind up at the complex in Abbotabad.

But is bin Laden there? Now that debate begins, mostly in D.C. Maya’s there for it, of course. In a meeting with the CIA director (James Gandolfini), never named but obviously Leon Panetta, others, including Dan, offer weak probabilities, 60 percent maybe, that bin Laden is in the compound. Then Maya pipes up. She’s 100 percent certain. After a second she amends it to 95. Not because absolute certainty is impossible but because she knows it scares the shit out of her colleagues. The director smiles. He likes her toughness. We like it, too, or we’re supposed to, but Maya never annoyed me more than at this moment. There’s a scene in the second “Godfather” movie, the Hyman Roth birthday-cake celebration on a rooftop in Cuba, in which Michael correctly predicts the Cuban revolution. It’s a cheap device: having fictional characters get real history right with the 20/20 hindsight of screenwriters.

Eventually they follow Maya’s lead, we meet Seal Team Six, and … you know.

The facts as we know them

Did you miss the link between torture and bin Laden in that synopsis? I missed it the first time I saw the movie because I forgot how Abu Ahmed’s name was first introduced. I thought Maya came armed with it. Instead it emerged after two years of torture.

Last month I said such a link would dispute the facts as we know them. I said it would be a lie. In the movie, Dan keeps telling Anmar, “When you lie to me, I hurt you,” and I think critics and pundits are saying the same thing to Kathryn Bigelow. When you lie to us, we hurt you.

But is it a lie? Last week, Acting CIA director Michael Morell wrote an internal memo in which he talked up the film’s inaccuracies. In so doing, he actually muddied the waters. He said the film’s impression that enhanced interrogation techniques were key to finding UBL is false. Then he wrote:

As we have said before, the truth is that multiple streams of intelligence led CIA analysts to conclude that Bin Laden was hiding in Abbottabad. Some came from detainees subjected to enhanced techniques, but there were many other sources as well.

In refuting the film’s falseness, he actually lays bare its truth.

In The Washington Post, meanwhile, Jose Rodriguez, Jr., a 31-year CIA veteran who headed up some of these programs, says that both the film and the film’s critics get it wrong. Enhanced interrogation did lead to intel that led to bin Laden. But it wasn’t the kind of interrogation shown onscreen. They waterboarded with small plastic water bottles, for example, not rusty buckets. He also objected to the Jessica subplot. Maya’s friend and rival, Jessica, thinks she has a mole in al Qaeda and agrees to meet him at a U.S. military outpost in Afghanistan. She’s portrayed as giddy, almost silly, baking a cake for his arrival. It’s as if it’s a date. She’s worried he won’t show. When he does, she’s worried that the guards at the gates will scare him off, so she gets them to stand down. Then she, and he, and several military officers are blown up. The character, says Rodriguez, is based on a real CIA officer. He writes: “The real person was an exceptionally talented officer who was responsible for some enormous intelligence successes, including playing a prominent role in the capture of al-Qaeda logistics expert Abu Zubaida in 2002. Her true story and memory deserve much better.” Not knowing this agent at all, I agree. The movie’s long as is, and this makes it longer, and it’s all telegraphed. Why make her seem like such a giddy girl on a date, for example? To make Maya look better? Does she need that? Doesn’t she have “100%”? Doesn’t she have “motherfucker”?

Yet the larger point remains. According to both of these CIA officers, enhanced interrogation, or torture, led to intel that led to bin Laden.

But is this right? Senate investigations are now being called to find out what Bigelow knew and when she knew it; what Bigelow was fed and how. At the moment, the truth isn’t out there.

But even though we don’t know the truth at the moment, is the movie still wrong?

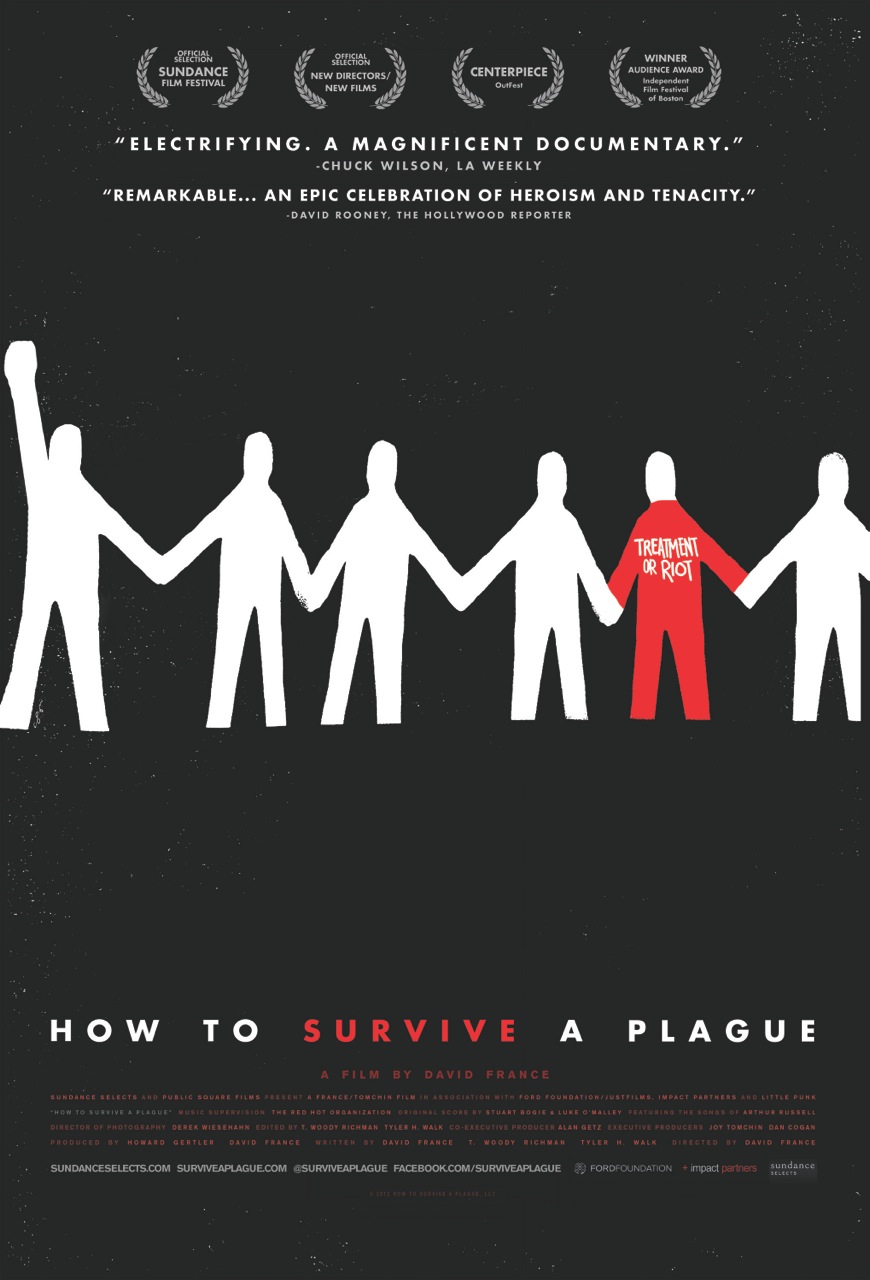

The lesson of the Central Park Five

To me it’s wrong because of what we learn in “The Central Park Five.” That documentary, which was also released in select cities in 2012, is about five kids, ages 14 to 16, who confessed to the infamous assault and rape of a jogger in Central Park in 1989, but who were innocent of the crime. Why did they confess? They got tired. They got worn down. They wanted to go home. After 14 to 30 hours of interrogation, none of it enhanced, the police were able to get innocent people to confess to horrific crimes. They got misinformation and it led to tragedy. The real rapist continued to rape and kill for another few months before he was caught. These boys were put away for 5 to 10 years. Nobody won.

In “Zero Dark Thirty,” we never have the wrong people. We always have the right people. And they always break. The movie’s right about that. Everyone breaks. Innocent people probably break sooner.

Mark Boal recently defended his film at the New York Film Critics Awards ceremony. He said: “I think at the end of the day, we made a film that allows us to look back at the past in a way that gives usa more clear-sighted appraisal of the future.” What’s that appraisal? I would say it’s this: Torture works. It’s a little immoral and a lot effective, and it prevents great tragedies. Yes, it’s messy. Yes, we get our hands a little dirty. But in the end we got bin Laden and that’s what matters. Because we never torture the wrong people.

A few years ago, I wrote an article on a civil rights lawyer named Robert Rubin. One of his cases involved a man named Hady Omar, whose story goes like this:

On Sept. 11, 2001, Omar’s flight from Florida was grounded in Houston, but he made it back to Fort Smith, Ark., and his American wife, Candy, in time for the FBI to pick him up the next day. He was targeted for: a) being Egyptian, and b) buying his plane ticket from the same Kinko’s in Boca Raton that one of the hijackers used. The FBI had questions but Omar wasn’t worried. The next day he took a lie detector test, passed, but instead of going free, the INS took him, in shackles, across state lines, to an office in Oakdale, La., then to a prison in New Orleans, then to a federal penitentiary in Pollock, La. There, while someone videotaped him with a camcorder, he was ordered to strip. There was a body cavity search, and jokes were made, and guards, including female guards, laughed. Finally he was placed in shackles in a 10-foot by 10-foot cell. He told officials he didn’t eat pork so he was served pork twice a day. His hot water was turned off so he stopped bathing. Days turned into weeks turned into months. He lost 20 pounds. He had thoughts of suicide. Finally, after 73 days without charge, he was freed. By then he’d lost his job and many of his friends—the front page of the Fort Smith paper on Sept. 13 featured a four-column photograph of Omar being led away in handcuffs under the headline: “Terror Strikes Home.” He and Candy were forced to sell their car and furniture; they moved in with her father. That’s when Rubin got involved.

Hady Omar got “lawyered up,” as they say in the movie.

Boal and Bigelow don’t show authorities incarcerating and interrogating men like Hady Omar, but it would’ve been easy to do so. There’s a perfect moment for it. When Debbie finds Abu Ahmed in a file folder, Maya wonders aloud why the information never got to her. There’s a discussion of all the misinformation flying around after 9/11. It’s implied that this misinformation came from other countries, probably Pakistan, who pretended to help but hurt. It would’ve been the perfect moment to bring up the innocent people who wound up in the detainee program. But for some reason Boal and Bigelow didn’t want to allude to that story.

Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln…

So how was the movie?

“Zero Dark Thirty” can be a slog. We never get to know our main character because she has no personality besides getting bin Laden. Most of the others are background figures. The most intriguing is Dan, who does his job well, and who has something of a thousand-yard stare in his eyes. He goes back early. He says he’s seen too many naked guys. It’s gallows humor. Jason Clarke does a great, understated job with the role.

I’ll say this: “Zero Dark Thirty” goes for veracity and mostly achieves it. But it screws up in this most important area. It misrepresents the efficacy of torture. It does so, at the least, by withholding information from us. And when you withhold information from us, we hurt you.

Tuesday January 08, 2013

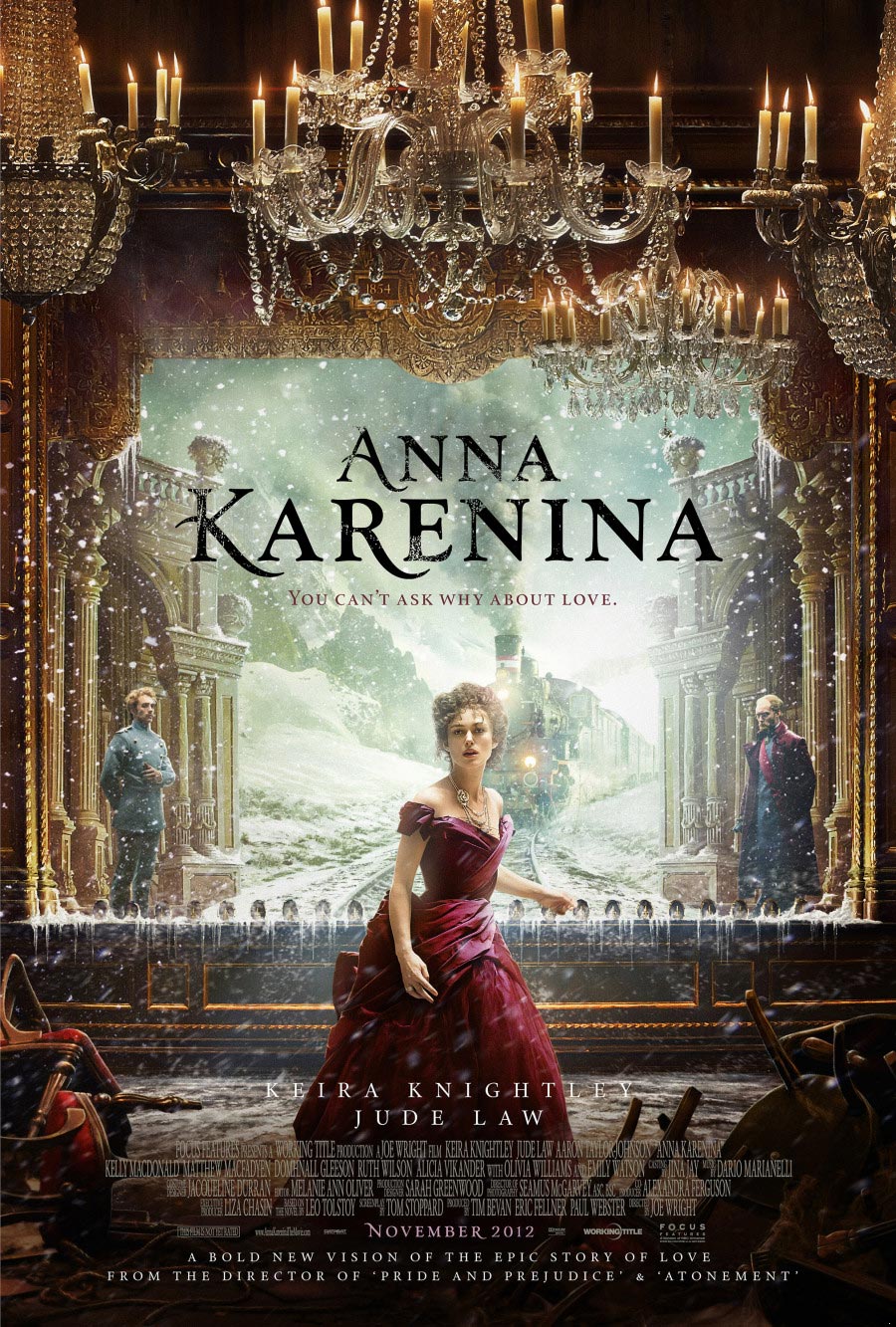

Movie Review: Anna Karenina (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I was worried I’d be bored with it since I already knew the story: Russia, married woman, affair, train. But I became intrigued by the purposeful staginess and theatricality from director Joe Wright. Or was that in the screenplay by Tom Stoppard? That’s a Stoppard staple.

It begins in a theater, on stage, with the words “Anna Karenina” on the curtain. I expected such theatricality to fall away, as it tends to in movies, and it does, at times, and we’re “in the scene” rather than “in the scene of the scene.” But it takes awhile to do this and the theatricality almost always returns—sometimes at  unexpected moments, such as at the end when Anna (Keira Knightley) is trapped by love and jealousy and society and doesn’t know which way to turn until she sees a way out. It was unexpected at this point in the story because I’d already equated this theatricality with the airs, theatricality and stagecraft in 19th-century Russian high society, of which Anna, here, was no longer a part. So why remind us? Someone with more time on their hands can go scene-by-scene and suggest why this scene dropped the cinematic illusion and that scene maintained the illusion. I’m sure Wright and Stoppard had their reasons.

unexpected moments, such as at the end when Anna (Keira Knightley) is trapped by love and jealousy and society and doesn’t know which way to turn until she sees a way out. It was unexpected at this point in the story because I’d already equated this theatricality with the airs, theatricality and stagecraft in 19th-century Russian high society, of which Anna, here, was no longer a part. So why remind us? Someone with more time on their hands can go scene-by-scene and suggest why this scene dropped the cinematic illusion and that scene maintained the illusion. I’m sure Wright and Stoppard had their reasons.

I got tired of the contrivance, to be honest. I’ve never been a fan of it. I suppose I think it’s the job of the storyteller to put me in the story and it’s my job, as listener or viewer, to take myself out of it. There’s a tyranny and pomposity to this kind of post-modernism as well as pointlessness. It’s weak tyranny. I will tell you when and where you will be taken out of the story, thereby weakening the story. I search for engagement with the story rather than removal from it. I object to the author’s strong hand on the back of my neck.

That said, there were times when the contrivance worked. I’m thinking of the moment Vronsky’s horse falls off the stage during the race—that was powerful—or when Levin (Domhnall Gleeson) gives up Moscow society for his country estate and leaves the suffocating artifice of the stage for the cold, harsh reality of the Russian winter. He turns, steps outside, and it’s as if we can breathe again. It’s as if we didn’t realize how much we were suffocating until that moment.

My Anna

It’s been decades since I’ve read “Anna Karenina”—final quarter of college, spring 1987—and I’d forgotten a lot of it. Levin, for example. Completely. Even though he’s half the story. He was my guy back then—in love, searching for meaning—but I found him harder to take here. I’m older now, and harsher. I watched his dull, youthful stabs at love and rolled my eyes. I almost felt like Levin’s Marxist brother, Nikolai (David Wilmot), who, dying, rails against the privileged classes, saying, “Romantic love will be the last illusion of the old order.” In 1987, that line would have pained me, as it no doubt pains Levin. Now I just shrug: “Maybe.” But I lack Nikolai’s conviction for what comes after. I saw the mess Nikolai’s brethren made of it.

At the same time, I was charmed by the flirtation, and the held-breath, of the game of blocks Levin has with his unrequited love, Kitty (the Swedish actress Alicia Vikander, with whom I was also charmed), later in the movie. By this point he’s suffered, she’s suffered (she loved Vronsky), and they’ve both matured. He’s in her parlor, visiting, and there are blocks there, and they play a game, almost like “Wheel of Fortune,” in which one side asks a question or makes a statement using only the first letter of each word, and the other side tries to guess what it is. In this way, this safe way, they reveal their feelings. DNMN, for example, from Levin, means, “Did No Mean Never?” referring to his earlier marriage proposal. TIDNK, she says, meaning “Then I Did Not Know.” And now? he asks. She asks, via the blocks, for his forgiveness for the way she was. He responds with these letters: ILY. No translation needed. That’s a sweet moment, and recalls the various wordgames from Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.”

In Tolstoy’s novel, I remember having more sympathy for Anna and less for Karenin, who seemed a prig to me. But as the movie progressed, I found myself less and less sympathetic with Anna, who gives up her child, etc., for her one great love, Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). Except Vronsky is, for the most part, shallow and callow. It’s a game to him, until it’s not, and Anna seems a fool for falling in love with him as completely as she does. Meanwhile, her husband, Karenin (Jude Law), publicly cuckolded, seems a decent, moral man who mostly tries to do the right thing.

Kundera's Anna

Our sympathies in this story are no small matter. Milan Kundera, in the last pages of his book of essays, “The Art of the Novel,” writes the following:

When Tolstoy sketched the first draft of Anna Karenina, Anna was a most unsympathetic woman, and her tragic end was entirely deserved and justified. The final version of the novel is very different, but I do not believe that Tolstoy had revised his moral ideas in the meantime; I would say, rather, that in the course of writing, he was listening to another voice than that of his personal moral conviction. He was listening to what I would like to call the wisdom of the novel. Every true novelist listens for that suprapersonal wisdom, which explains why great novels are always a little more intelligent than their authors. Novelists who are more intelligent than their books should go into another line of work.

But what is that wisdom, what is the novel? There is a fine Jewish proverb: Man thinks, God laughs. … Because man thinks and the truth escapes him. Because the more men think, the more one man's thought diverges from another's. And finally, because man is never what he thinks he is.

Maybe the movie needed more drafts. By the end, Anna, never particularly likeable, is insufferable. She’s mad with love, mad with jealousy, mad with loneliness. She thinks she can go out into high society again, and pretends it doesn’t matter what people think. It’s a shock when it does. By this point, I began to feel sorry for, all of people, Vronsky, who has to put up with her histrionics. Finally she sees her way out. She met Count Vronsky on a train and ends her life beneath one. It’s this story in a newspaper account of the time—woman throws herself beneath train—that led Tolstoy to write “Anna Karenina” in the first place.

“Anna Karenina” looks beautiful, is filmed gorgeously, and I loved Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky. But the story’s dilemma is truly the dilemma of another time and place. Attempts to bring the story to our time should bring some of its wisdom with it.

Monday January 07, 2013

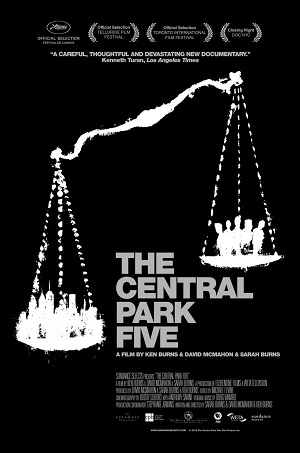

Movie Review: The Central Park Five (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

If they’d made a feature film about the Central Park Five—the five teenagers who were convicted in the brutal assault and rape of an investment banker jogging in Central Park on the evening of April 19, 1989—Jack Klugman, who played Juror No. 5 in Sidney Lumet’s “12 Angry Men,” would have been a good choice to play Juror No. 5, Ronald Gold, in the 1990 trial of three of the five. At the least, his casting would have highlighted the difference between the U.S. justice system in its ideal and its reality.

In “12 Angry Men,” Juror No. 5 is the second man to come over to Henry Fonda’s side on the movie’s ultimate path toward justice and a “Not guilty” verdict for the black man wrongfully accused of a crime. In the 1990 trial, Juror No. 5 was the lone holdout, the reason the jury deliberated as long as it did (10 days), on the court’s ultimate path toward injustice and a “Guilty” verdict for the five black kids wrongfully accused of a crime. The movies, even serious movies like “12 Angry Men,” are still so much wish-fulfillment fantasy. The real world is much, much sadder.

As for why did Juror No. 5 changed his mind and voted to convict? It’s the same reason the Central Park Five confessed to the brutal rape in the first place.

14 and 15, mostly

I remember the Central Park Jogger case well. I remember hearing about it on Sunday morning talk shows, sitting in the living room of my father’s house in South  Minneapolis in April 1989. I’d just spent a year abroad in Taipei, Taiwan, and was preparing for grad school at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, but the thing I was doing most that spring? Dating a girl. A girl who liked to jog at night. As a result, the thought of random acts of violence, particularly gang rape by packs of kids, self-professed “wolf packs” engaged in the sport of “wilding,” terrified me. I never even thought to ask if it was true. It was on the Sunday morning talk shows, after all.

Minneapolis in April 1989. I’d just spent a year abroad in Taipei, Taiwan, and was preparing for grad school at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey, but the thing I was doing most that spring? Dating a girl. A girl who liked to jog at night. As a result, the thought of random acts of violence, particularly gang rape by packs of kids, self-professed “wolf packs” engaged in the sport of “wilding,” terrified me. I never even thought to ask if it was true. It was on the Sunday morning talk shows, after all.

“The Central Park Five” by Ken Burns, Sarah Burns and David McMahon, begins with an audiotape confession. “I’m the one that did this,” it says. It’s chilling. Questions immediately present themselves. If these five kids didn’t do it, how did they get accused in the first place? How was this injustice done?

In ordinary ways, it turns out. In ways that will feel familiar to any viewer of “The Wire.”

The five were in Central Park that night. Raymond Santana, Sr. remembers sending his son there. He told him there was too much trouble on the corner, that the park was safer. This parental concern ruined Raymond Jr.’s life. Raymond Sr. knows it. You can see it in his eyes. He lives with it every day.

I’d forgotten how young the kids were—if I ever knew. Korey Wise was the oldest at 16. Raymond Santana, Jr. and Kevin Richardson were the youngest at 14. Antron McCray and Yusef Salaam were both 15.

They each became part of a gang of kids, anywhere from 25 to 32 in number, who, that evening, messed with people on the north side of the park: throwing rocks at cars; knocking over cyclists; beating up a homeless person. Each of the five, in the doc, claims he wasn’t doing any of the messing; each professes a kind of shock that this behavior was even going on. But they stuck around and the cops came, and Kevin, Yusef and Raymond Santana, among others, were detained at the Central Park Precinct and questioned about the incidents. They were about to be released when a homicide detective working on a rape case across the park telephoned. “Hold onto those guys!” he said.

A homicide detective was working the case because the jogger was in coma; she’d lost three-quarters of her blood. They didn’t think she was going to make it. But at least they had suspects. They had 25 to 32 of them. Within a day, five had confessed.

Why the innocent plead guilty

There was an article in The New York Times the other day about a rape case in West Virginia in which DNA evidence now suggests that the man who had been convicted of the 11-year-old crime, the 19-year-old who had confessed to it back then, didn’t do it. Barry Scheck of the Innocence Project condemns the prosecution. An assistant prosecutor fights back. “Raping an 83-year-old lady is about as bad as it gets,” he says. “Why would someone plead guilty and say they were sorry several months later if they really had no participation in it?”

That’s what we want to know watching “The Central Park Five.” Why would these kids, if they didn’t do it, confess to this horrific crime? The answer we get sheds a little light on the world. It helps explain not only the Central Park case but the West Virginia case. It explains why Ronald Gold finally voted to convict. It explains why we went to war in Iraq.

The detectives interrogated the kids for 14 hours, 20 hours, 30 hours. They said they’d already been fingered by other kids in the gang. They said, “Hey, these other kids say you did it. Now we know you didn’t, but…” They offered them deals. They demonstrated anger and conviction. They didn’t let up.

“I just wanted it to stop,” one of the Central Park Five says.

“I just wanted to go home,” says another.

They were 14 and 15 years old and thought if they confessed to parts of the crime—the holding the woman down, say—they’d be able to go home. Instead they walked out of the police station and into a media maelstrom. Feelings were hot. Grandstanding took place. Donald Trump placed an ad in the local papers demanding the return of the death penalty. Members of the mainstream media called the boys “sociopaths” and “mutants.” Even many in the black community went along. “Many of us were frightened by our own children,” says Rev. Calvin O. Butts III.

All of this created a momentum for conviction. Yet without their videotaped confessions, which were quickly recanted, there was no evidence linking them to the crime. The New York Police Dept.’s own timeline placed the boys about a mile from the ravine at the time the rape took place. The trail of matted grass from the path to the ravine was only 18 inches wide, meaning they’d had to walk it single-file. Most telling of all, despite the ferocity of the attack, they’d left none of their DNA behind: not in the woods; not in the woman. The police had DNA, yes, but it was someone else’s. “I felt like I’ve been kicked in the stomach,” prosecutor Elizabeth Lederer told a colleague when she discovered this.

But the case continued; it had momentum. At the trial, on the stand, the police denied that they had coerced confessions; they denied making deals. And they had the confessions. “It was hard to imagine why someone would make up [a guilty plea when they were innocent],” Ronald Gold, Juror No. 5, says in the doc. He was the lone holdout for conviction. He says the other jurors even called him a rat for holding out. So, he says, “I went along with it in the end.” He says, “I was wiped out.” He voted guilty for the same reason the boys lied about being guilty. He got worn down. He just wanted to go home.

A modest nod

Most of the Central Park Five got 5 to 7 years. Korey, the eldest, was put away for 10 years. He was still there, at Riker’s Island, in 2001, when he crossed paths with Matias Reyes, who had been arrested in August 1989 and convicted shortly thereafter on multiple rape charges. He was known as the East Side Rapist. He did horrible things. He also raped and assaulted the jogger that night in Central Park. When he saw Korey still in prison for his crime, something in him stirred, and he confessed, the confession we hear at the beginning of the doc. When his DNA was compared with the DNA found at the scene, it was an exact match.

In December 2002, when the state of New York vacated the convictions of the five, I was working as a freelance writer in Seattle. I was probably working on a story for Washington Law & Politics. I was plugged in. But unlike April 1989, I don’t remember hearing about the case. “These were five kids who we tormented, we false accused, we pilloried in the press, we invented phrases for the imagines crimes” says historian Craig Steven Wilder. “And then we put them in jail. And when the evidence turned out that they were innocent, we gave a modest nod and walked away.”

“Central Park Five” is a straightforward, well-researched, powerful documentary, although I would’ve like a subtler ending. I also would’ve liked more on what led to the term “wilding,” which never existed until the police mentioned it in connection with this crime. How did it come about? David Dinkins mentions Emmett Till as historical reference point but no one brings up the Scottsboro Boys? That’s what I kept thinking. I kept thinking that for all the distance we’d traveled, we hadn’t gone that far.

But this is really less a story of race than coercion. It’s about the powerless, yes, but it’s a warning to the powerful. When you’re powerful, and committed, and you go searching for something, you’ll find it. You’ll find it because you’re powerful and committed. Even if the thing you’ve found is the wrong thing. Even if the thing you’ve found is the opposite of the thing you were searching for. Here, for example, we went searching for justice.

Wednesday January 02, 2013

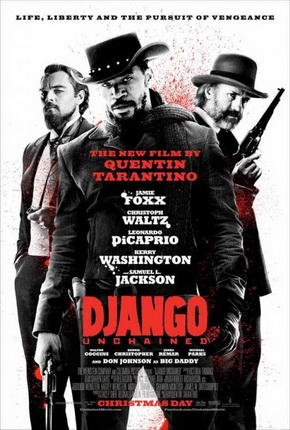

Movie Review: Django Unchained (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The slaughter of Native Americans? The rape of Nanjing? The near-genocides of Josef Stalin or Pol Pot? What is the next historic horror Quentin Tarantino will turn into a spaghetti-western-style revenge fantasy? In the 1990s, QT gave us three complex, pulpy crime stories (“Reservoir Dogs,” “Pulp Fiction,” “Jackie Brown”), and in the aughts three female revenge fantasies (“Kill Bill” I and II and “Death Proof”), and now he’s given us two revenge fantasies of an historical nature: the rising up of the historically downtrodden. “Inglourious Basterds” showed us Jews killing Nazis, including Uncle Adolf, once upon a time in Nazi-occupied France. Now, in “Django Unchained,” a freed slave, Django (Jamie Foxx), kills slavemasters in the deep South—or more specifically, as it’s scrolled across the screen in big 1950s type, M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I—in 1858. “Two years before the Civil War,” QT adds helpfully.

It’s a great idea. History is nothing but groups of people being fucked over, while the movies are all about wish-fulfillment fantasy. So why not meld the two? The Bible is full of revenge fantasies as well. Maybe that’s the next direction? “Quentin Tarantino’s The Bible.” That’s a title he’d dig. He’d dig it the most, baby.

The more-or-less true story of the bounty hunter

Question: Who holds the power in a Quentin Tarantino story? More than the one with the weapon, it’s the one with the story. His movies are conversations punctuated by violence, and the one who holds the floor holds the power.

This is apparent more than halfway through “Django Unchained” when Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) momentarily loses the conversational thread to Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Schultz actually looks confused at the dinner table. Someone is telling a story and it’s not him. He should know that when the talking is done a gun will be pointed at his head, since that’s how he usually ends his stories. It’s really this, getting one-upped in storytelling, more than the dogs tearing apart the runaway slave d’Artagnan (Ato Essandoh), that later bothers Schultz. That’s why he: a) insults Candie, and, b) shoots and kills him. He must know he’ll die as a result. But he has to do it. The man can’t abide getting one-upped in storytelling. I’m sure Tarantino, an inveterate storyteller, feels the same way.

This is apparent more than halfway through “Django Unchained” when Dr. King Schultz (Christoph Waltz) momentarily loses the conversational thread to Calvin Candie (Leonardo DiCaprio). Schultz actually looks confused at the dinner table. Someone is telling a story and it’s not him. He should know that when the talking is done a gun will be pointed at his head, since that’s how he usually ends his stories. It’s really this, getting one-upped in storytelling, more than the dogs tearing apart the runaway slave d’Artagnan (Ato Essandoh), that later bothers Schultz. That’s why he: a) insults Candie, and, b) shoots and kills him. He must know he’ll die as a result. But he has to do it. The man can’t abide getting one-upped in storytelling. I’m sure Tarantino, an inveterate storyteller, feels the same way.

The storytelling is what’s right with “Django.” It also indicates where Schultz, or QT, goes wrong.

The power of Schultz’s stories is that they’re more-or-less true. In the beginning, he really is interested in buying the slave, Django, from the slave traders who are moving Django and four others across Texas in 1858. He comes upon them in the middle of the night, driving his absurd little stagecoach with the large plaster tooth bobbing comically on top. The tooth is subterfuge, since he hasn’t worked dentistry in five years. But he is interested in buying Django for a fair price. He’s a bounty hunter, tracking the three Brittle brothers (great name), but he’s never seen them. Django has. That’s why he wants him. But the two white men, the slave traders, aren’t interested in his long-winded story, nor his fancy-pants European vocabulary, and they try to cut his story short, not to mention his bargaining, at the point of a gun. That’s our first shootout. Schultz kills one, leaves the other beneath his own horse, but still pays for Django. Because his story is true.

His next story is even better because every element of it, in the telling, seems crazy, but in the end it all pulls together.

Schultz rides into Daugherty, Texas, accompanied by, as everyone says, “a nigger on a horse.” That freaks them out right away. Then he actually brings Django into a saloon, which is closed for another hour. When the saloonkeeper flees, he pours himself and Django beers and tells him of his plans. He says he’s against slavery, but, for the moment, somewhat guiltily, he’ll use it, and Django, to get the Brittle brothers and the bounty on their heads. After that, he’ll set Django free. Deal? By this time the sheriff, Bill Sharp (Don Stroud), shows up, and Schultz, while explaining matters, shoots and kills him in the muddy Texas street. Now everyone’s freaking. But rather than attempt to escape, Schultz nonchalantly returns to the saloon, keeps telling his story to Django, and let’s opposition forces, led by the local Marshal (Tom Wopat), gather outside. When the Marshal demands he give himself up, he first exacts the concession that no one will shoot him on sight; that he’ll get a fair trial before being hanged by the neck. The Marshal reluctantly agrees. So he walks outside into the gauntlet of guns, unarmed but with a story. Their sheriff? Bill Sharp? He isn’t who they think he is. He’s a wanted man, with a bounty on his head, and Schultz is a court-appointed bounty hunter, and that’s why he killed him. He has the piece of paper in his pocket to prove it. “In other words, Marshal,” he adds, trumping everyone, “you owe me $2,000.”

Nice. And the main reason it works is because it’s true.

The mostly false story of the Mandingo slaver

In this manner, Dr. King Schultz and Django move through the Midwest and South telling stories, killing men, collecting bounties. Sometimes the stories aren’t enough, as when Django kills two of the Brittle brothers in the presence of Big Daddy (Don Johnson), who then gathers a posse, an early version of the Ku Klux Klan, to kill the nigger and the nigger-loving German. But King knows when his stories aren’t enough and he’s ready for them, with dynamite (patented in 1867, but whatever). The purpose of the Kluxers is comic relief. Before they ride, they complain about the hoods with the eye slots. How they can’t see. How they can’t breathe. Can they just not wear them? It’s the funniest part of the movie.

King even tells Django a story around a campfire. It’s the story of Brynhildr. It resonates because Django’s wife, who was whipped by the Brittle brothers and resold into slavery, is named Broomhilda (Kerry Washington). She was raised by Germans, speaks some German. That’s an interesting coincidence, by the way. The slave that the native German bounty hunter needed to collect a bounty has a wife who speaks German. Here’s another: Schultz learns, by and by, that the slave he bought and freed also turns out to be the fastest gun in the South. Too many coincidences like these can get in the way of a good story. We begin to question the things we’re hearing or watching. Where was that chain gang of slaves going at the beginning of the movie anyway? How did Dr. King Schultz find them in the middle of the night in the middle of Texas? And how did he find them coming the other way? If he was pursuing Django, wouldn’t he be catching up to them? Too many coincidences make us wonder if the storyteller is a bad storyteller; or if he’s just lying to us.

The power of Schultz’s stories in the first half of the movie is that they’re true. He goes wrong—and you could say Tarantino goes wrong—when he begins to lie.

Schultz and Django, partners now, discover that Broomhilda has been sold to Calvin Candie, of Candieland (great name), in the deepest part of the South: M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I. How to get her back?

Schultz gives a quick reason why they don’t rely on some version of the truth. I forget what it is. I also don’t understand why they don’t use the story he uses in the end: He’s German; he misses speaking German; might he, perchance, buy the slavegirl who speaks German? Calvin Candie isn’t an unreasonable sort. He’s also a bit of a slave to Southern hospitality. I’m sure he would’ve acquiesced to this request for a fair (or unfair) price. Using this scheme, Schultz wouldn’t even have had to bring Django with him to Candieland. And since the heat between Django and Broomhilda is what tips off the house slave Stephen (Samuel L. Jackson), who alerts his master, leaving Django back in town, or up North, might have averted the bloodbath that follows.

But that’s the thing. Schultz, the storyteller, is interested in averting bloodbaths. Tarantino, the storyteller, is not. In fact, he needs the bloodbath or the movie isn’t a Tarantino movie. It’s just full of words. It’s not cool. A few years ago, in “Not Quite Hollywood: The Wild, Untold Story of Ozploitation!,” a documentary about Australian exploitation movies, Tarantino said the following about how the low-budget thriller, “Patrick,” nearly influenced “Kill Bill”:

I always remember that actor. I thought he was amazing-looking in that movie with his eyes just wide open and everything, and in the original script [for “Kill Bill”] I had it written like that. Then I showed it to Uma and she goes, “I'm not going to do that,” and I go, “Why?” and she goes, “You wouldn't have your eyes open like that if you were in a coma! That's not realistic.” I go, “Actually I never thought was it realistic or not, it's just Patrick did it, alright, and it looked really cool.”

That’s always been the problem with Tarantino. Given the choice between realistic and cool, he always goes for really cool.

The battle of the remaining storytellers

So Schultz concocts the false story, the made-up story, of wanting to purchase a Mandingo wrestler, while his companion, Django, a freed slave, is his advisor in the matter. Eventually they’re uncovered. The rest of the movie becomes, in a sense, a battle of the storytellers.

First, Calvin Candie, discovering the subterfuge of Schultz and Django, doesn’t just go into the dining room with guns cocked; he goes in there with a story. It’s a story meant to reassert white superiority over the Negro. It involves a hammer, and a skull, and dimples in an area of the skull, and it ends with the hammer coming down.

After Candie and Schultz have been killed, our next storyteller is Stephen. By this point, Django has killed many white folks, which, yeah, you don’t do in M-I-S-S-I-S-S-I-P-P-I, and the question becomes what to do with him. The white folks have the same old ideas: lynching, castration, dogs. But Stephen has a thought. Lynch Django and he becomes a legend for everything he’s already done. But force him to live out his days in subservient toil, for, say, the LeQuint Dickey Mining Co. of Australia, until he dies old and frail and useless, well, that will lessen his legend. It will change the trajectory of his story. That’s how he even puts it to Django. He imagines the day when Django finally keels over from overwork in the mines and tells him, “And that will be the story of you.”

And it might have been. But “Django Unchained” isn’t just a revenge fantasy. It is, to use the German, a bildungsroman, in which our protagonist, Django, mentored by Dr. King Schultz, moves from the darkness of slavery and into the light of absolute, fuck-you freedom. From Schultz, he learns about bounty hunting and guns. He learns how to dress and how to kill. And by the end, he’s learned how to tell a story, too. Sold to the Aussies, he uses this power. He tells them they’ve been lied to by the folks at Candieland, who claimed Django was a slave; he tells them that there is bounty-hunting wealth beyond imagination back at Candieland if they just want to go back and claim it. This story has the advantage of being mostly true, and the other slaves, too dim and scared to lie, corroborate it. So the Aussies, straight out of an Ozploitation movie, set Django free and die. And Django returns to rescue Broomhilda and put a final end to Stephen, the house nigger, and to Candieland itself. He blows it up, puts on his sunglasses, and rides off into the sunset with his girl.

And that, says Tarantino, is the story of him.

The story of the storyteller

So what’s the story of Tarantino? It’s changed over the years, hasn’t it?

First, it was the story of the videostore clerk who became a hot screenwriter and director. Then it became the story of the auteur who employs favorite or forgotten actors. He started with Travolta in “Pulp Fiction,” moved onto Pam Grier and Robert Forster in “Jackie Brown,” and never really stopped. “Django Unchained” gets its name from the great spaghetti western “Django,” starring Franco Nero, so we get Nero, of course. He’s the dude at the bar at the Cleopatra Club who asks Django how his name is spelled. “The ‘D’ is silent,” Django says. “I know,” Nero says with a proud smile. Another cool, false moment for QT.

Other forgotten actors in “Django” include the aforementioned Don Johnson, Tom Wopat and Don Stroud; Dennis Christopher of “Breaking Away” as the Cleopatra Club owner; Lee Horsley of TV’s “Matt Houston,” and Ted Neeley, Jesus Christ Superstar himself, as one of the trackers whose hounds tear apart the runaway slave d’Artagnan. Neeley hasn’t acted on screen since 1985.

More recently, though, the story of Tarantino for me is the story of the auteur who never really lived up to the promise of “Reservoir Dogs” and “Pulp Fiction”; who, when given the choice between realistic and cool, always goes with cool, no matter how false it may be. He needs to learn the lesson of Dr. King Schultz. When you tell your story, try to make it more-or-less true. Make it so true that you can end it, and trump your enemies, with a piece of paper rather than a gun. Because in the end that’s cooler.

Saturday December 29, 2012

Movie Review: This is 40 (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I laughed a lot during “This is 40,” Judd Apatow’s comedy of middle-aged angst, but he needs to rein in his performers. Or himself. Too many times it felt like people were doing bits, for which they had commitment, for which their commitment to the bit was the whole point, rather than simply being characters in a story that was moving forward. As a result, the story didn’t move forward. It stalled. The movie clocked in at 134 minutes. You could watch “Annie Hall” in that time and still have 40 minutes left over for pizza.

Here. At one point, Pete and Debbie’s daughter, 13-year-old Sadie (Maude Apatow), has a dust-up on Facebook with classmate Joseph (Ryan Lee), which Pete and Debbie (Paul Rudd and Leslie Mann) become aware of. Debbie subsequently runs into Joseph at the school when she’s having a bad day and lets him have it. She calls him a little hairless wonder, compares him to Tom Petty, says his hair looks like a Justin Bieber wig on backwards. Then she adds:

Here. At one point, Pete and Debbie’s daughter, 13-year-old Sadie (Maude Apatow), has a dust-up on Facebook with classmate Joseph (Ryan Lee), which Pete and Debbie (Paul Rudd and Leslie Mann) become aware of. Debbie subsequently runs into Joseph at the school when she’s having a bad day and lets him have it. She calls him a little hairless wonder, compares him to Tom Petty, says his hair looks like a Justin Bieber wig on backwards. Then she adds: