Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

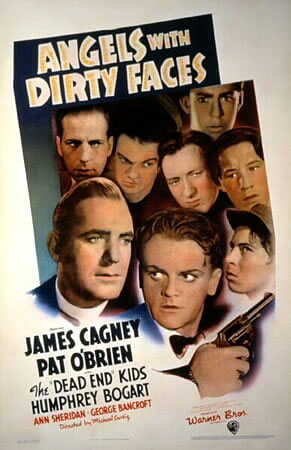

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

Cagney by Cagney

by James Cagney

(As told to John McCabe)

James Cagney's philosophy - Do the work, don't overthink it - makes for a great life but a semi-disappointing memoir.

DoubleDay & Company

202 pages

1976

Out-of-Print

Excerpt:

"Around this time my brother Ed, just out of a sickbed, had been badly beaten up by a local boy, Willie Carney... That night a kid came up to our flat breathlessly to announce that Careny was fighting with a kid down the block. I arrived in time to see the boy stretched out, and I promptly told the boy I'd take his place. I gave Carney a chance to rest, and then we went to it. We were going at it hot and heavy when the cops arrived and broke it up. By arrangement we met the next night and were slugging away when the cops raided that one, too. The third night we kept slugging away, but he just refused to fold. I had great admiration for that spunky guy because he took my best punches with style..."

Trivia:

The Motion Picture Academy nominated James Cagney Best Actor three times in his career. Name the movies.

Cagney By Cagney still has the subject's forthright spunk and wonderfully anachronistic vernacular ("ham-and-egging it..."; "knocked me galley west"), plus his vivid descriptions of growing up on the lower east side of Manhattan at the turn of the (last) century. But once he gets to Hollywood, he reels off picture after picture without telling us much about the Hollywood process, and, worse, he's a sourpuss about many of the movies his fans probably love - in this sense, sounding like Francis Ford Coppola's constant complaints about the making of The Godfather. It's a memoir reminiscent of Jackie Robinson's, in that it seems to dismiss the very reason he became famous in the first place.

Remember in Yankee Doodle Dandy when a young George Cohan played Peck's Bad Boy who felt he could "lick any kid in the neighborhood," but who, when the tough neighborhood kids actually came around, folded beneath a hail of refuse, stones, and fists? That wasn't Cagney. "The biggest claim to fame in our neighborhood was when you could throw a punch," he writes. Cagney could. He is of two contradictory minds about the fights he and his brothers participated in: That it wasn't out of the ordinary ("We weren't exceptional"), and that it was ("You think I want to get killed?" a neighborhood boy tells his sister when she asks him to beat up the Cagney brothers). The man who played tough guys was definitely a tough kid.

There were four brothers in all - Harry, Jimmy, Eddie and Bill - and a sister, Jeanne, born when Cagney was already an adult. Their mother was a tough Irish Catholic lady, and their father a handsome, light-on-his-feet ladies man who died at the age of 41. How tough was their neighborhood? In the late teens, when Cagney's Sunday baseball team, the Nut Club, traveled to Sing-Sing to play the prison team, he came face-to-face with several old acquaintances, including a kid named Bootah, who had killed a cop, and who would get the electric chair in 1927. As for why the Cagneys didn't wind up in similar circumstances, Cagney writes, "We had a mother to answer to. If any of us got out of line, she belted us, and belted us emphatically." He adds, so as not to confuse anyone, "We loved her profoundly, and our driving force was to do what she wanted because we knew how much it meant to her."

For a time he considered prize-fighting but his mother nixed this quickly. He then did odd jobs, including a stint as a runner for a brokerage house; but the work was boring and show business was exciting. His first real gig, ironically (considering his eventual tough guy status), was in a female impersonation act called Every Sailor.

Vaudeville shows and specialty dancing jobs followed - including a vaudeville three-act called "Parker, Rand and Cagney" which had once been "Parker, Rand and Leach," i.e., Archibald Leach, i.e., Cary Grant. (One wonders: Whatever happened to Parker and Rand? At the least, they chose their partners well.) Eventually Cagney reached Broadway. One play, Penny Arcade, closed after only three weeks, but Al Jolson saw it, took an option on it for the pictures, and Cagney was asked to come to Hollywood. "I came out on a three-week guarantee and I stayed, to my absolute amazement, for thirty-one years."

It was William Wellman who helped make him a star. Cagney did Penny Arcade (renamed Sinner's Holiday because "There was a great vogue then for pictures with 'holiday' in the title"), and in his next picture, Doorway to Hell, he played the quiet pal of a Capone-like gangster. In Public Enemy, Cagney was again cast as the quiet pal to Edward Woods' "tough little article" Tom Powers, and may have been destined for second-banana roles forever. "Fortunately," he writes, "Bill Wellman, the director...quickly became aware of the obvious casting error... so Eddie and I switched roles after Wellman made an issue of it with Darryl Zanuck." The film made Cagney a star - a grapefruit to the face of Mae Clark didn't hurt either - and the only evidence of the switch, as I've mentioned elsewhere, is in the childhood scenes, where the tall boy grows up to be Cagney while the short pug becomes Ed Woods. His sudden fame didn't immediately lead to more money, though. When he came out to Hollywood he was signed to a three-week, $500 per week contract, which later became a 40-week, $400 per week contract. A nice sum during the Depression, but he was actually making less as a star than when he first arrived, and much less than the $125,000 per picture other stars were making. In those days studios forced exhibitors to "block book" pictures, meaning, according to one Boston exhibitor "I had to take five dogs to get one Cagney film." Learning this, and fed up with the assembly-line process of making bad movies, Cagney began a series of walk-outs that resulted in higher pay, and eventually - with the help of other actors - in the Screen Actors Guild.

A lot of stars didn't think Hollywood would last in those days - Clark Gable, for example, refused to buy anything he couldn't take back on a train with him - and Cagney recalls warning his friend, Pat O'Brien, "'Pat, stop and take stock... Is this thing going to give us security for the rest of our lives?' But Pat never listened." Oddly, Cagney never corrects himself on the matter, because Pat was right, the thing did give them security for the rest of their lives, and Cagney eventually retired to Martha's Vineyard and upstate New York on his Hollywood money.

He tired quickly of Hollywood - the rat-a-tat-tat quickness of movie-making, the blandness of the scripts which he and his fellow actors would attempt to punch up. He says as much about Angels with Dirty Faces, my favorite Cagney flick, but his example of "punching up" involves Catholic procedures, and, for non-Catholics, probably didn't add much to the quality of the picture. Memorably, though, he admits that Rocky Sullivan was based on a pimp from his old neighborhood:

He tired quickly of Hollywood - the rat-a-tat-tat quickness of movie-making, the blandness of the scripts which he and his fellow actors would attempt to punch up. He says as much about Angels with Dirty Faces, my favorite Cagney flick, but his example of "punching up" involves Catholic procedures, and, for non-Catholics, probably didn't add much to the quality of the picture. Memorably, though, he admits that Rocky Sullivan was based on a pimp from his old neighborhood:

He worked out of a Hungarian rathskeller on First Avenue between Seventy-seventh and Seventy-eighth streets - a tall dude with an expensive straw hat and an electric blue suit. All day he would stand on that corner, hitch up his trousers, twist his neck and move his necktie, lift his shoulders, snap his fingers, then bring his hands together in a soft smack. His invariable greeting was "Whadda ya hear? Whadda ya say?"... I did that gesture maybe six times in the picture - that was over thirty years ago - and the impressionists are still doing me doing him.

At the same time it was a dangerous business. They were still using real bullets during the gunfights, and Cagney came close to getting killed several times during his career. Plus his rep as a tough guy led to many a "backyard weight lifter" calling him out. No wonder Cagney insists he's simply "an old song-and-dance man." Fewer fights that way.

Throughout the memoir Cagney is gracious to old friends Pat O'Brien and Frank McHugh, Ralph Bellamy and Spencer Tracy, and less so with co-star Humphrey Bogart, whom he remembers as a nose-picker and a man depantsed by the Dead End Kids. The book is padded with his poetry, which ain't that good, and his various philosophies, which are short and sweet. On acting: "You walk in, plant yourself, look the other fella in the eye, and tell the truth." He dismisses method acting (too internal) and those yearning for stardom, since, "...one should be aspiring to do the job well." In this he is a 19th century man. Fame didn't interest him as much as a job well done. To a friend hurt by criticism he offers this sound advice: "Just ask yourself one question and the hurt will disappear that fast. The question is this... 'Who the hell do I think I am?'"

Cagney by Cagney is strictly for Cagney fans, but it's been out-of-print for years so you'll have to search. I found my copy, fittingly enough, at the Strand Bookstore in Greenwich Village, just a couple of blocks south of old Broadway.

óNovember 25, 2002

© 2002 by Erik Lundegaard