Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

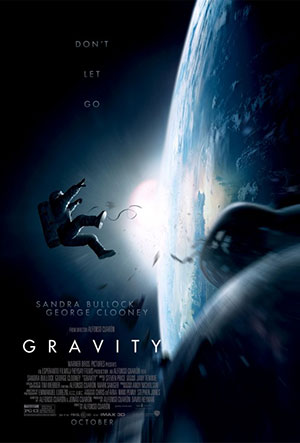

Gravity (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Is “Gravity” the new Hollywood spectacle?

The original kind, created in the wake of television, tended to be overlong, wide-screen, supersaturated Biblical epics. Hollywood studios were trying to give you an experience you couldn’t get in your home. They were trying to get you out of your home and away from your TV set. This type of spectacle was eventually replaced by epic musicals (“Sound of Music,” etc.), which were replaced by director-driven films with sex and/or violence (“Bonnie and Clyde,” etc.), which were replaced by the ascendance of B-movie fodder with A-movie production values (“Star Wars,” etc.). We’re still in this last period, more or less, but Hollywood studios are still looking to give you something you can’t get in your home. They’re trying to entertain you away from your home entertainment system.

| Written by | Alfonso Cuarón Jonas Cuarón |

| Directed by | Alfonso Cuarón |

| Starring | Geroge Clooney Sandra Bullock Ed Harris (voice) |

“Gravity” is short: 90 minutes. It’s a novella of a movie. It promises, not a cast of thousands, but a cast of two. For much of the movie, in fact, it’s just one. It’s “Castaway” in space.

But it’s still a kind of experience, particularly with IMAX and 3-D, that you can’t get in your home. It’s an event.

But how’s the story?

In space, no one can hear things explode

“Gravity” opens beautifully. We see the Earth, boom, in front of us, huge, and surrounded by the silence of space. Then writer-director Alfonso Cuarón (“Children of Men”; “Y Tu Mama Tambien”) holds on it. And holds on it. Then, slowly, people and voices come into view. They rotate into view.

It’s the five-person crew of the Explorer, a U.S. ship in orbit. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), a medical engineer tethered to the Explorer, is attempting to fix a motherboard outside the ship. Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), astronaut, an old space hand, jets about, filling the vast silence of space with his cynical, amused charm. “Houston, I have a bad feeling about this mission,” he jokes. He tells well-worn or half-finished stories about his wife leaving him, about New Orleans in the 1980s, about how he’s going to come up short of breaking the space-walk record set by Anatole Somethingorother. He’s a George Clooney character: He knows his business, he knows the score, he’s been broken in some way but charm seeps through the cracks.

For the moment, Ryan is resisting that charm. She lives up her family name. She’s lost in her work.

Not for long, though. The Russians have destroyed one of their satellites, and this has destroyed others, setting off a chain reaction of orbiting destruction, with the Explorer directly in its path. This storm of debris arrives like a silent meteor shower, and Stone is torn from the Explorer and goes rocketing and flipping through space. Earlier, when asked what she likes about being up there, she replied, “The silence.” Here, she finds out how frightening that silence can be. Here, she’s grateful when she finally hears a human voice, Matt’s, in her radio transmitter. He urges calm. He tells her what to do so he can find her. Then he brings her back to the ship.

But the Explorer is no longer a ship, simply more space debris, and the rest of the crew are dead. There’s no radio contact with Houston. They’re alone up there. But Matt has a plan.

See that light over there? That’s a Soyuz space station. They’re going to head over there, Ryan tethered to Matt, Stone to Kowalski, and take one of its capsules back to Earth. But beware the orbiting space debris. By his calculations it will return in 90 minutes.

There are other things to worry about, too. They arrive just as she’s running out of oxygen and he’s running out of jet fuel. (Why does he not run out of oxygen? Isn’t he the one doing all the talking?) Worse, Soyuz is damaged, they bounce off it, and Ryan almost goes flying off into the void, forever, but her feet get tangled in the cords of a deployed parachute. Matt is less lucky. He sees that she won’t make it unless he lets go. So he lets go.

And then there was one.

The roller coaster

Other movies come to mind watching this one. “Alien,” obviously. (Terror in space, female survivor.) “Barbarella,” oddly. (A woman removing her spacesuit in zero gravity.) “Castaway,” as above.

But the dominating influence is Steven Spielberg. “Gravity” is a roller-coaster ride with smarts and art and, well, gravity, but it’s still a roller coaster ride. It’s still skin-of-the-teeth stuff. For 90 percent of the movie, Ryan is staying just one small step (rather than one giant leap) ahead of destruction, until the final, beautiful shots when her capsule splashes to earth, she crawls to shore, and pulls herself up on the land. You almost feel the weight of gravity holding her in place then. It’s a great shot. “Gravity” begins well and ends well, and the middle is a ride. But it’s just a ride.

Within this ride, yes, Cuarón and company do some good work. We get a bit of background. We find out Ryan lost a child, a girl, 4 years old, and when she died much of Ryan’s reason for living died with her. She shut herself off. She almost does that here. In Soyuz, before traveling to the Chinese space station, Tien Gong, she powers down the systems, turns off the air, gives up. She’s ready to die. She’s ready to join her daughter.

Then a knock on the door.

No joke. At first I thought it was one of the cosmonauts—the face looked gigantic and grotesque—but it’s actually Matt, the sexiest man alive, who has miraculously survived. He enters the spacecraft and fills it with his energy. Did you find the vodka? he asks. Well, I finally broke the spacewalk record, he says. Now let’s take this puppy home. It’s a great moment, even if it doesn’t seem reasonable—given the verisimilitude of everything else in the movie—and it isn’t. It’s a dream. A figment. Matt’s dead, she’s alone, but the moment—the dream, the vision, whatever—inspires her to try again. The whole scene is really well-done. I was happy when Matt returned (we needed something), and I was sad he turned out to be a figment, even as I realized it was the right thing to do for the story.

A helluva story to tell

So they do good things within the ride, but is it enough? Is Ryan an interesting enough character to hold the screen by herself for half the movie?

At one point, Matt, or maybe his figment, tells Ryan why she needs to keep trying: You’ll either die, he says, or you’ll have a helluva story to tell.

When you see “Gravity,” see it on an IMAX screen with 3-D. Make it an event. Because for all its spectacle, for all its effects, “Gravity” doesn’t have a helluva story to tell.

—October 8, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard