Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

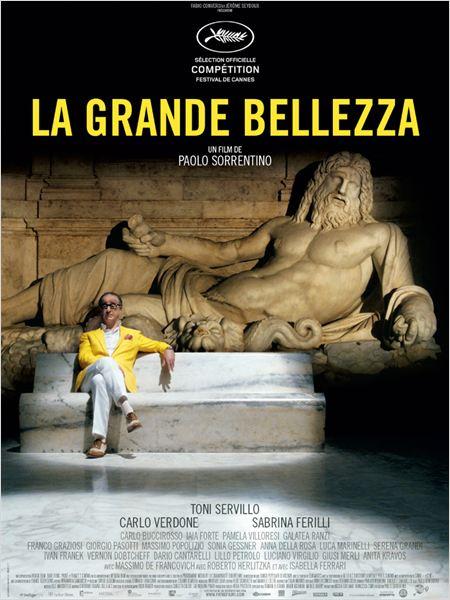

La Grande Bellezza (2013)

Warning: SPOILERS

Paolo Sorrentino’s “La Grande Bellezza” (“The Great Beauty”) is well-named. Sure, it’s episodic and goes on a bit long (148 minutes), and I kept seeing endings before the ending. Oh, it’s going to end here. Then it didn’t. Or here. No. But its ending was a good ending, probably better than the other endings I felt. Above all, it’s beautiful to look at and to contemplate. It’s pungent in its beauty.

Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), 65, wise in his age, bemused in his stance, idle with his time, is on a sort of search. He’s not searching for meaning so much as a reason to keep going. At one point he says, “I can’t waste any more time doing things I don’t want to do,” and this is just before he disappears rather than look at the naked photos of a beautiful woman, Orietta (Isabella Ferrari), he just slept with. So: high standards. At another point he sees a giraffe, a beautiful giraffe staring down from on high and surrounded by a half-circle of ancient Roman columns; and the two, Jep and the giraffe, stare at each other until Jep’s magician-friend arrives and explains the giraffe. It’s part of his act. He makes it disappear. And Jep leans close and asks, “Can you make me disappear?” That’s when we realize the extent of Jep’s ennui. He shows the world a bemused face, but inside, particularly in the morning light after another party, he’s desperate. His magician-friend has to tell him that if he could make people disappear he wouldn’t be where he was. “It’s just a trick,” he says.

| Written by | Paolo Sorrentino Umberto Contarello |

| Directed by | Paolo Sorrentino |

| Starring | Toni Servillo Carlo Verdone Sabrina Ferilli Carlo Buccirosso |

A life in tatters

On the surface, Jep has little to complain about. He’s a spry 65, still living the sweet life, la dolce vita, in modern-day Rome, with friends, parties, work, women, and a beautiful apartment with a balcony overlooking the Colosseum. I’m talking the fucking Colosseum. He came to Rome at 26 and got sucked into the whirl of the high life, and he didn’t just want to be part of it; he wanted to be its king. He wrote a slim novel, acclaimed, called “The Human Apparatus,” and has been living off of that, and a few writing gigs and interviews for major magazines, ever since. He wants to write more but wine, women and parties keep getting in the way.

Sound familiar? It’s basically the dilemma of Marcello Rubini, Marcello Mastroianni’s character in Fellini’s “La Dolce Vita.” Rubini kept getting sucked into la dolce vita, which wasn’t (dolce), while Jep keeps searching for la grande bellezza, which, ultimately, is (bello).

We get disconnected, sometimes absurd scenes a la Fellini. Jep watches a performance artist, naked but for a diaphanous hijab, run into an ancient stone structure, then declare, to the outdoor audience, “I don’t love you!” to applause. Turns out he’s interviewing her for his magazine and with a smile refuses to accept any of her “artistic” responses. He tries to get to know his neighbor, who refuses to speak, and hosts parties on his balcony, to friends who refuse to shut up. He gets into it with one friend, a beautiful woman and Communist Party member named Stefania (Galatea Ranzi). She brags about all she does, the children she’s raised, the 11 books she’s written, and refuses to see the lies she lives with every day. She demands he gives examples. He does, to the discomfort of everyone else, and with that same sad smile on his face. Then he says this:

Stefania, mother and woman, you’re 53 with a life in tatters like the rest of us. Instead of acting superior and treating us with contempt, you should look at us with affection. We’re all on the brink of despair. All we can do is look each other in the face, keep each other company, joke a little. Don't you agree?

That’s not a bad end philosophy but we’re still near the beginning of the movie. So what can our man learn?

This? The great love of his life, Elisa, seen in flashback (Anna Luisa Capasa), dies, and her husband of 35 years comes to Jep in tears, telling him “She always loved you.” He’d cracked her diary and read her thoughts and he barely comes up in them. “Thirty five years and I’m mentioned as a ‘good companion,’” he says. Jep tries to comfort him, though he’s secretly thrilled, though later in the movie it’s Jep who wants answers. Elisa, long ago, left him so he wants to know why she did this if she loved him, and he asks if he can read that diary. But by this point it’s been burned. By this point the widower is now with another woman, and happy again, and life continues.

Jep gets involved with a woman, Ramona, the daughter of an old friend. She thinks he’s after sex but he’s more interested in the her of her, and maybe in the distraction of it all. The sex comes later. So does death.

There are great lines throughout. Stefania calls him a misogynist, and he replies that he’s a misanthrope not a misogynist—a line I swear I’ve used in the past. Much later they’re dancing at an outdoor function and they have this exchange—lines which I wish I’d used in the past:

Jep: Have we ever slept together?

Stefania: Of course not.

Jep: That’s a big mistake. We must make amends immediately.

Why doesn’t the companion of Jep’s dwarf publisher ever speak? “Because he listens.” Why are the trains, the conga lines, at Jep’s parties the best? “Because they go nowhere.” For a movie I feared would not be about character or dialogue, this one has great examples of both.

Your earlier, funnier movies

Probably the key question of the movie is this: Why did Jep never write a second novel? Everyone wants to know. Even a future saint.

Near the end, Jep is hosting Sister Maria (Giusi Merli), a 103-year-old nun who has worked her whole life with the poor. She has handlers, a PR man who answers questions, so for a time we don’t even know if this husk of a person, this toothless, wrinkled woman, can speak. But finally she does. And one of the first things she says is: “Why did you never write a second novel?” It’s like the running gag of “your earlier, funnier movies” in Woody Allen’s “Stardust Memories,” which is itself a takeoff on Guido’s “next movie” in Fellini’s “8 ˝.” Homage upon homage.

And it’s here that Jep finally gives an answer. “I was looking for the great beauty,” he says, smiling his sad smile. “But ... I didn’t find it.” It’s around this time that Sister Maria gives her own answer to an oft-asked question. The rumor is that she eats only roots. People want to know why. So she tells Jep. “Do you know why I only eat roots? Because roots are important.”

Is this her advice about finding the great beauty? Does this help him, in the end, find the great beauty? By the end, he’s writing a novel anyway. We get its beginning in a voiceover. “So let the novel begin,” he says. “After all, it’s just a trick.”

“The Great Beauty” is a movie I could see again, and not just because it’s beautiful but because I’m curious about all that I missed amid its swirl. Jep, like Marcello before him, straddles the profane and the sacred, the great pointlessness and the great beauty. One assumes the two are inexorably intertwined; that if you are lucky enough, you suffer through one to get to the other. But that’s too neat, too definite. “The Great Beauty” is more open-ended. It opens its arms wide and lets you enter.

—December 15, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard