Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

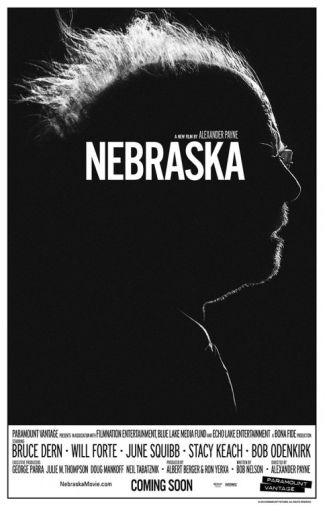

Nebraska (2013)

Warning: SPOILERS

In “Nebraska,” David Grant (Will Forte), a middle-aged man with a crappy retail-sales job and a nowhere life, offers to drive his grizzled, alcoholic father, Woody (Bruce Dern), who believes himself to be a million-dollar sweepstakes winner, the 900 miles or so from Billings, Mont., where they live, to Lincoln, Neb., the headquarters of the publishing house offering the prize. Along the way, circumstances compel them to stop in Hawthorne, Neb., where Woody grew up, for a visit with aunts, uncles, cousins, friends. These people are generally reticent, dull, and, once Woody’s suspect bounty is revealed, greedy. They are also without hope and opportunity, living in a dead-end town in a dead-end part of the country during the dead-end of the global financial meltdown. It’s a comedy.

| Written by | Bob Nelson |

| Directed by | Alexander Payne |

| Starring | Bruce Dern Will Forte June Squibb Stacy Keach Bob Odenkirk |

What to make of “Nebraska”? It’s beautifully photographed (black and white), and doesn’t feel false, necessarily, since we all have distant relatives that seem dull and dimwitted. But there’s usually more to them, isn’t there? Even if the more is less? Hardly a racist word is spoken here, for example. Just something about “Jap cars” and even that racism seems old. It’s circa 1991. Or 1941.

No, the Grants’ distant relatives are just comic relief. They add to the sad absurdity that is Woody’s quest. The women gather in the kitchen to gossip and the men gather in the living room to watch television in silence. If they’re old, they fall asleep on the couch. If they’re young, they drink beer on the porch. David has two cousins like that, Bart and Cole (Tim Driscoll and Devin Ratray), who stare at him with bug eyes, belittle his driving abilities (and, implied, manhood), and late in the game actually rob Woody of his sweepstakes announcement. They seem like characters John Candy could have played on SCTV.

At the same time, I was rarely uninterested in “Nebraska.” It affected me. Its tone sank into my bones like gray weather.Problems with the basic premise

The opening image is a static shot of a nondescript part of Billings. In the distance, an old, grizzled man (Woody) walks towards us on the thin strip of grass between an unmoving railroad and a constantly moving highway: between the static past, you could say, and the constantly moving present. A cop stops him and asks, over the roar of the traffic, where he’s headed. Woody points toward us. And where is he coming from? Woody points back. Cue credits. At this point, I was ready to love the movie.

But I had trouble getting beyond its premise. Why would David agree to take his father to Lincoln to collect nothing? Isn’t his father suffering the early stages of Alzheimer’s? And isn’t David’s own life going nowhere? He’s a clerk at an electronics store, lives in a flimsy apartment, wishes to start up a relationship again with a woman he doesn’t love. His life is sad sad sad. Does he have ambitions? Hopes? Fears? Who is he?

Later, David talks about his reasons for the trip: 1) He wants to get out of Billings; 2) he wants to spend more time with the old man; and 3) he wants the old man to shut up about the million dollars. Reasons 1 and 3 I can see, but 2? Who wants to spend days in a car with Bruce Dern?

I know, cheap shot, but this may be an instance where good casting works against a movie. Dern is getting acclaim for the role—best actor at Cannes, etc.—and he’s good, but a premise of the movie, a third-act revelation, is that David is “just like his father.” Really? David is too kind and too passive. He goes along to get along. So we’re supposed to believe that this cantankerous, alcoholic old man, played by Bruce Dern of all actors, was kind and passive in his youth? Have the filmmakers seen “Coming Home”? “The Great Gatsby”? “Marnie”? Anything?

For the impromptu family reunion in Hawthorne, both David’s mother, Kate (June Squib), and his more successful brother, Ross (Bob Odenkirk), join them. I like how both sons are played by comedians. I like how Ross is more successful but not a jerk. I didn’t like the mother’s outlandishness. Too much. When she hiked up her skirt at the cemetery to show a former beau what he was missing? Like that.

By this point Woody has blabbed about his winnings and everyone’s believed him, and when the family says, “No, he didn’t really win a million dollars,” everyone thinks it’s an attempt to shake them off the scent. Folks begin behaving badly. So do the Grants. Some of it’s funny. Mostly it’s just sad.

And all the while we’re wondering this: How can the filmmakers—director Alexander Payne (“The Descendants”) and first-time screenwriter Bob Nelson—give us a satisfying end? What can this road trip bring but more disappointment?

Here’s how. They make David even kinder than we thought he was, with access to more money than we thought he had.

Prize winner

In Lincoln, David and Woody walk into the home office of the publishing house, a nondescript building in a nondescript part of town, and a nondescript woman greets them. They say why they’ve come, she takes Woody’s announcement and punches the numbers into her computer. Sorry, she says. You didn’t win. Then she offers a consolation: How about a cap or blanket? He chooses the cap. He puts it on. It reads: PRIZE WINNER.

Why did he want the million dollars? That’s a question that’s come up several times in the movie, absurdly to me, since who wouldn’t want a million dollars? Money means opportunity and options. It means the end to the dead-end. But it’s asked, and Woody replies that he always wanted a brand-new truck (even though his driver’s license has been taken away), and an air compressor (even though he no longer has use for one). He also wishes he had a little something to leave his sons. He doesn’t like the idea of leaving them nothing.

“You should’ve thought of that before you threw your life away,” David replies.

Kidding. David doesn’t say that. Instead, in a used-car lot in Lincoln, he trades in his Japanese car for an American truck. Then he buys his father a useless brand-new air compressor. Then they return to Hawthorne and David lets Woody drive the truck slowly down Main Street.

It’s a sweet moment, a not-bad resolution. At the same time, it requires us to believe that everyone that matters to Woody in Hawthorne, former loves and current enemies, would be in the proper place at the proper time to see his one-man victory parade. It also requires us to believe that David has more disposable income than we were led to believe.

But that’s our end. And off they ride, a debt-ridden father and son, into a black-and-white American sunset.

I wanted to like “Nebraska.” But it portrays us as both better (David) and worse (almost everyone else) than we really are.

—December 11, 2013

© 2013 Erik Lundegaard