Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

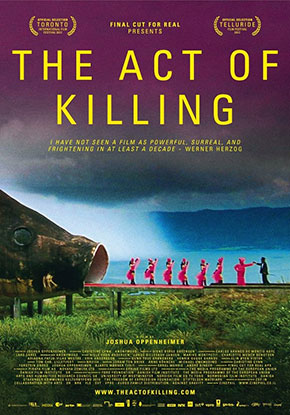

The Act of Killing (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Holy shit.

That’s what I kept saying watching Joshua Oppenheimer’s documentary, “The Act of Killing.” Holy fucking shit.

Not many movies mix the horrific and absurd as thoroughly as this one. It’s as if Paulie Walnuts had been backed by the U.S. government to kill people up and down the east coast, and thousands were tortured and killed; then years later he sat back and bragged about it for the cameras; then he restaged the killings and expected the low-budget results to be as good as “The Godfather.”

In Indonesia 1965, Anwar Congo was a “movie theater gangster.” He hung out at movie theaters, scalped tickets, took in the shows. He loved Hollywood movies. He loved Elvis, and Brando, and left the theater in a good mood. Often he carried his good mood across the street where he tortured and killed people for the government. Sure, he had a few bad dreams, but the government he helped stay in power is still in power, its enemies silenced, and those enemies—communists, et al.—would have done bad things if he hadn’t stopped them. Right? So he did good stopping them. Why should he worry?

Then he met filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer.

“Free men”

When we first see him, Congo is tall and thin, white-haired and venerable-looking. He looks kindly. Dare I say like Nelson Mandela? Except Mandela’s face in old age was beautiful, while this one is pinched. It’s often blank. Something’s missing.

Initially it’s Congo’s partner, Herman Koto, younger, overweight, pugnacious, who does the talking. We watch as he negotiates with people to get them to play-act for the cameras. They pretend to be communists whose homes he and his men are burning. They do it. They scream in fake anguish while Koto and his men, wearing loud, Hawaiianish shirts—the uniform of the Pemuda Pancasila, Indonesia’s paramilitary, right-wing death squad, we find out later—shout, “Burn it! Kill them!” Then someone shouts “Cut!” and everyone applauds. All this time, Congo hangs in the background. It’s as if he doesn’t want to get his hands dirty.

But eventually he begins talking.

Congo: We have to show ...

Koto: ... that this is our history.

Congo: This is who we are. So in the future people will remember.

There was too much blood. That was the problem at the beginning, and Congo came up with a more efficient method—garroting with wire—to kill the state’s enemies. He proudly demonstrates on a friend on a rooftop where many killings took place. Both men smile for the camera. Then Congo talks about the various ways he numbed the pain—booze, drugs, dance—but he doesn’t seem to be in much pain. He does the cha-cha for us. His friend stands to the side awkwardly. “He is a happy man,” his friend says.

Later, Oppenheimer allows Congo to watch these scenes, and he’s disturbed by them. He knows something’s wrong. Is it his hair? He dyes it. Is it his teeth? He gets false ones. He should be like a movie gangster but he’s not. It should be like in a movie but it’s not. Something’s missing.

He travels and meets old friends. There’s Syamsul Arifin, the current governor of North Sumatra, whom Congo looked after as a boy. “Now that I’m governor, I stab him if he threatens me,” Arifin says, and everyone laughs, even Congo, but without humor. Isn’t he the star of his movie? Should he be the butt of jokes this way?

All of the old gangsters talk up the old days. They badmouth the communists. They keep repeating that the word gangster means “free men.” Does it? In Indonesian? Or is this another lie they tell themselves to get through the day?

“Now the communists’ children are speaking out,” Arifin says with disgust, “trying to reverse the history.”

But it’s not reversed. Watch the credits. Count the number of times the word “Anonymous” appears. It’s more than 60. This film was made by people who fear its subjects; who fear reprisal. The making of “The Act of Killing” is an act of courage.

Monster, realized

Is it also an act of redemption?

The deeper we get into the doc, the more absurd the attempts at recreation—the movie within the movie—become. There’s a huge set piece, the burning of huts, and villagers are dragged away to be killed. “You acted so well,” Koto attempts to comfort one little girl, tears streaming down her face. “But you can stop crying now.” Eventually we get the scene at the beginning and end of the doc. It’s a big dance number at the foot of waterfalls. Dancing girls come out of the mouth of a giant fish. They sing. They surround Anwar Congo (hair dyed, dressed like a priest) and Herman Koto (in drag), and the dead and the tortured bestow upon Congo a gleaming medal; then they all lift their arms up to the sky and sing about peace.

All together now: Holy fucking shit.

Most of the time, the movie gangsters simply try to emulate the Hollywood gangsters they’ve always loved. They put on suits and fedoras and restage torture scenes. They put on makeup that suggests facial lacerations. They take turns being torturers and tortured. But they know something’s wrong. On screen, they’re not the heroes they are in their minds.

Near the end, Anwar Congo actually breaks down. He’s filming a scene in which he’s blindfolded and tortured and he begins to cry. He talks to the doc’s director, standing offscreen. Joshua Oppenheimer is British-American, born in Texas and now based in Copenhagen, who sounds fluent in Indonesian. He sounds like he’s earned the trust of these men. This is what Congo says to him:

Did the people I tortured feel the way I do here? I can feel what the people I tortured felt. Because here my dignity has been destroyed, and then fear comes.

It’s an amazing moment. His first of empathy? More amazing is Oppenheimer’s response. He doesn’t try to comfort him. He simply tells him the truth:

Actually, the people you tortured felt far worse because you know it’s only a film. But they knew they were being killed.

Congo listens like a child and reacts like a child, insistent on his new empathy:

But I can feel it, Josh. Really, I feel it. Or have I sinned? I did this to so many people, Josh. Is it all coming back to me? I really hope it won't. I don't want it to, Josh.

Is this some small redemption for Anwar Congo? Is the monster less monstrous if he realizes the monster he’s been?

Hooray for Hollywood

More, is this a redemption for film in general?

How much do the movies inure us, blind us, unite us with the powerful onscreen rather than the powerless? To what extent do we take the lies of Hollywood from the theater and try to recreate them in our own lives? And is that what the various movie gangsters, including Anwar Congo, did in 1965 and 1966? Did they see themselves, even as they took lives, as the heroes in their own Hollywood movie?

However the movies worked upon the mind and soul of a man like Anwar Congo, it was acting in a movie, this one, that helped him rediscover his empathy. So does “The Act of Killing” ultimately redeem movies? Or does it only redeem acting?

We watch “The Act of Killing” with a sense of horror because of what’s portrayed onscreen but also because of what it does to our worldview. It crumbles it. If a society can exist where murder and slaughter is celebrated, joyfully and abundantly, what does that say about human morality? Is it not merely a construct? Is there nothing universal in “Thou shalt not kill”? Put it this way: I’m a relativist and even I felt the crumbling of my worldview. So even I was relieved by the 11th-hour contrition of Anwar Congo. It made the world right again.

Maybe it shouldn’t have.

“War crimes are defined by the winners,” one of the death-squad leaders says in the film.

Indeed. But winners are not absolute. Time keeps choosing new ones.

—January 12, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard