Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

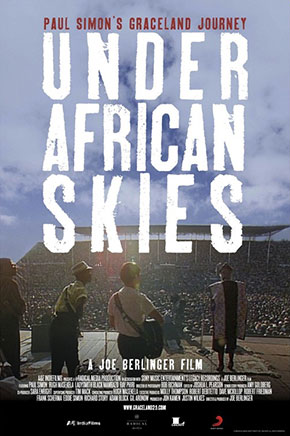

Under African Skies (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Early in Joe Berlinger’s “Under African Skies,” a documentary about the making of Paul Simon’s “Graceland” and his return to South Africa 25 years later to perform a concert with the various South African musicians with whom he worked—including drummer Isaac Mtshali, guitarist Ray Phiri, and vocalist Joseph Shabalala of Lady Blacksmith Mambazo—music is compared to both religion and to the voice of God.

“It’s only 12 notes, man,” Quincy Jones says to Simon, both old men now, sitting on a couch in 2011. “That’s what music is—the voice of God. Don’t you think?” Simon pauses a moment before answering, sincerely, “Yes, I do.”

I don’t know about the voice of God but it makes me happy. Paul Simon’s music makes me happy. This documentary certainly made me happy. I left the theater with a stupid grin on my face, went home, and immediately downloaded a digital version of the album. I had it back when, as either LP or CD or cassette tape, but had neglected it during the crossover into MP3s.

Politics vs. girls in short skirts

Remember the controversy it caused? A different time. Nelson Mandela was in his 22nd year of 27 years of captivity, F.W. de Klerk was president, Apartheid was enforced by police truncheon and gun. In response, the African National Congress, or ANC, initiated an economic and cultural boycott of South Africa. Simon, by showing up for two weeks in 1985 to record his album, and by employing black South African musicians, broke that boycott. You don’t play Sun City and you don’t work with Lady Blacksmith Mambazo. Simon was condemned in South Africa, London, and at Howard University. During the “Graceland” world tour, there were protests outside concert halls and bomb-sniffing dogs inside concert halls. It was, says Dali Tambo, the son of then-ANC president Oliver Tambo, “an issue.”

To be honest, I never got it. An economic boycott of black musicians to protest the oppression of black people? Wouldn’t that be like boycotting Ray Charles in 1955 to protest Jim Crow laws? It feels like the wrong people were being punished. Or, as Ray Phiri says here, about his own reaction to the controversy, “How can you victimize a victim twice?”

The doc tries to sort through the controversy—then and now—while presenting, via archive footage and talking heads, the long process of how the album came together. Here’s how we got that accordion riff at the beginning of “The Boy in the Bubble.” Here’s how Ladysmith Black Mambazo came into the picture. At one point Simon wondered whether these songs shouldn’t be political, since he wasn’t blind to what was going on. He felt the tension in the country and in the room. Shouldn't the album reflect this tension? So he asked the South African artist, General M.D. Shirinda, about the song that became “I Know What I Know,” which was based on one of Shirinda’s songs. What were its original lyrics? Shirinda responded thus: “Remember in the sixties when girls wore short skirts? Wasn’t that great?” So much for politics.

The lyrics, interestingly, weren’t written until Simon returned to New York. He agonized over them. He came up with “There’s a girl in New York City who calls herself the human trampoline,” but recognized its very New Yorkness. How did it fit with the African rhythms? He kept coming back to a riff, “I’m going to Graceland,” tried to shake it, couldn’t, then threw up his hands and decided he’d better go to Graceland. At one point he realized—as I never did in 1987—that Graceland didn’t have to mean Elvis; it could be a metaphor for a state of grace, a place where “we all will be received.”

In this way, the album came together. One gets a sense of the arbitrariness of it all. It could’ve easily have gone another way.

Greater good vs. greater music

Some of the more touching moments in the doc are about the opening of the world to these South African musicians, most of whom had been working odd jobs until Simon came along. They didn’t know who he was. For some, he was their first white friend, the first white man they hugged, a revelation. “Who’s this guy hiding himself in America?” Joseph Shabalala remembers thinking. “He’s my brother.” They were flown to New York to finish the recording and a limo with a white driver met them at the airport. They wanted to go to Central Park and asked “Where do we get a permit?” They wound up on “Saturday Night Live” singing “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes” and became a sensation. A world tour, plagued by the ANC controversy, followed.

Dali Tambo, now with an odd 19th-century-style moustache, happily provides the ANC’s perspective. He and Simon sit on another couch, this one in Tambo’s home in South Africa, for a discussion/argument on what happened. Basically: the ANC felt the greater good was served by subsuming the individual to the nation’s needs; Simon felt the nation’s needs were served by giving the world individual faces and voices. The oppression was no longer an abstraction; here were the people being oppressed.

Mostly, though, he just wanted to make good music.

“It’s the same event but everybody’s story is different,” Simon says at the outset, but of course the doc gives us his story rather than Tambo’s. Even the talking heads favor the artist since they’re artists themselves: Philip Glass and David Byrne and Peter Gabriel and Paul McCartney. Oprah Winfrey talks about how she heard of the controversy and determined to avoid the album; then she heard the album. “It’s my favorite album of all time,” she says now. She became more deeply interested in South Africa because of “Graceland.” You could say Simon wins his argument with Tambo right there.

49 vs. 13

There are a few cloying moments—the close-up of Simon’s white hand in Tambo’s black hand—but mostly the movie is joyous: a celebration of music and artistry and creativity and brotherhood. It’s also a celebration of a time when music seemed to matter more than it does now. What gets big now isn’t necessarily worthy of big. Feel free to dismiss that as the perspective of a 49-year-old curmudgeon.

Of course, once upon a time, I was a 13-year-old curmudgeon, arguing with friends that Paul Simon’s music was better than the Bee Gees’ music. I don’t have such arguments anymore; they seem ridiculous to me. I like what I like and I know what I know. And who am I to blow against the wind?

—May 24, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard