Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

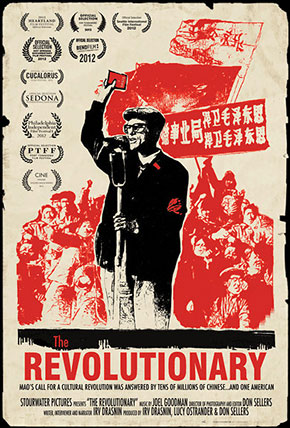

The Revolutionary (2012)

WARNING: GANG OF SPOILERS

“You missed it.”

That’s what Ben Bradlee tells Woodward and Bernstein after reading one of their early Watergate stories in “All the President’s Men,” and that’s what I thought leaving the world premiere of “The Revolutionary,” a documentary, locally produced, about 91-year-old local Sidney Rittenberg, who, as a high-ranking member of the Chinese Communist Party from 1946 to 1980, was once called “The most important foreigner in China since Marco Polo.”

Rittenberg was a labor lefty out of Charleston, South Carolina in the 1930s, when everyone in labor was a lefty, before the politics of resentment meant resenting those with less rather than more; and then, like everyone else, he was drafted after Pearl Harbor. Unlike everyone else, he was taught Chinese and sent to China. After the war, Chinese party leaders asked him to stay. “We need an engineer to help us build a bridge from the Chinese people to the American people,” they said. He asked to be a member of the party. He stayed. He felt content. “I’m doing what I should be doing,” he felt.

He had his own long march to Yan’an in 1946, where he met Mao Zedong for the first time. “It’s like a picture out of history,” he remembers thinking, “and I’m now part of that history.”

This is big for Sidney Rittenberg: being part of history.

He’s told Mao wants to spend two days talking about America but we don’t get that conversation. He says Mao wanted good relations with the U.S. because he didn’t want to be dependent on the U.S.S.R. He says the U.S. was thinking ideologically here and Mao wasn’t.

There’s a nice interlude about the Hollywood movies Mao, Zhou Enlai and other party leaders watched each week. Laurel and Hardy movies were favorites.

Then Chiang Kai-shek and the Kuomintang are driven to Taiwan, the Communists come to power, and, when the dust clears, Rittenberg, a man who had Mao’s ear, is suddenly imprisoned as a capitalist spy. He winds up in Beijing Prison No. 2, in solitary confinement, for six years. His Chinese wife divorces him. He nearly goes insane. “Every day,” he says. “you’re sitting there with your own potential madness sitting across from you. Watching you. And you know it’s either you or him.” He was finally released, he believes, “Because Josef Stalin did the best thing he ever did in his life: He died.”

A more far-seeing man, or a man less enamored of China and/or communism, might have left Communist China at this point, but Rittenberg was not that man. He went to work for Radio Beijing, got remarried, had four kids—who mostly go unmentioned. We hear from his wife briefly in the doc.

That may be the doc’s biggest problem. Except for a minute’s worth of monologue from Wang Yulin, his second and current wife, this is a single-source news story. It’s just Rittenberg talking in a chair, or in front of his book shelf, or at other strategic points in his home in the Pacific Northwest. Every once in a while the camera pans over a period photo or a propaganda poster. But we get no footage from China, no supplementary interviews with people who knew him, no references to the newspapers of the day. Did Rittenberg’s defection, such as it was (he never renounced U.S. citizenship), make the newspapers back home? He’s not mentioned in The New York Times, for example, until Linda Charlton does a write-up upon his return in 1980: ‘Son of America’ Is Home to Tell About Chinese In-Laws. (But I had to look that up after the screening.) Did the Charleston papers write about him when he was in China? Did The Daily Worker? Did the CIA?

If Rittenberg was a wiser, more insightful man, the single-source issue wouldn’t be such an issue. He says of Mao, “He was a great hero and a great criminal all rolled into one,” which feels true to me, but of his own life, at least as relayed in this doc, there’s an odd disconnect. He, or documentarians Lucy Ostrander, Irv Drasnin and Don Sellers, can’t seem to connect the fragments of his life into a narrative that makes much sense.

As a foreigner in Communist China, which became increasingly xenophobic as the Great Leap Forward leads to the Cultural Revolution, he seems self-deluded or myopic. When he’s put into solitary confinement again in 1967, he concocts his own Confucian saying: “Man who climbs out on limb should listen carefully for sound of saw.” He says he couldn’t hear the sound of the saw until it was too late. But he could never hear the sound of the saw. That’s his problem.

He remained in solitary until 1977.

What was the appeal? That’s what I still don’t get. Was it the communism? Was it China itself? Was it both? Was it being part of history? Does he regret those days? Is he a communist now? A socialist? A capitalist? Is he capitalist now the way that China is capitalist now? What happened to his four kids when he was in solitary and Wang Yulin was being reeducated? Did they become members of the Red Guard? Did they denounce their parents? Were they denounced themselves for being half-American?

Nothing.

I’m also not a fan of the narration, performed by Irv Drasnin, a former news correspondent, because his voice has the deep, faux authority of a former news correspondent. At times it reminded me of the narration in those 1950s Disney nature films that we were forced to watch in elementary school. It’s a voice both deep and cloying. It has all the answers and it’s there to tell us the way the world works. It grates.

The story of Sidney Rittenberg and his time in China is a good story. I hope someday a documentarian will be engineer enough to build a bridge between it and an audience.

—June 7, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard