Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

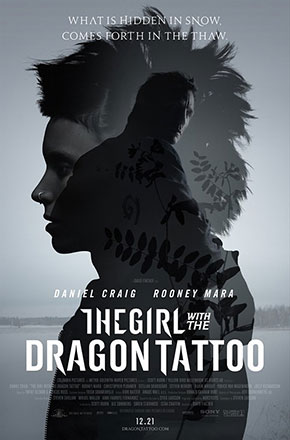

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2011)

WARNING: SPOIL YOU, YOU SPOILING SPOILERS

I believe in Lisbeth Salander.

The movies offer us a new ass-kicking heroine every other week, it seems: Angelina Jolie, Charlize Theron, Zoe Saldana. Even Natalie Portman tried her little hand last year. Even 12-year-old Chloe Moretz.

I don’t believe in any of them. But I believe in Lisbeth Salander.

She’s not fighting men three times her size in hand-to-hand combat. She takes them down with guile and tools and fury and ruthlessness. She either meticulously plans and strikes or just grabs a golf club and strikes.

One of the great moments in the Swedish version of “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo” (“Män som hatar kvinnor”) occurs near the end, with the golf club, after Lisbeth (Noomi Rapace) rescues a tied-up and tortured Mikael Blomkvist (Michael Nyqvist), and then, on her own, chases down Martin Vanger (Peter Haber), the neo-Nazi serial killer and general sick fuck who was torturing him. Let me repeat that. The bad guy was torturing him and she came to the rescue. Then she didn’t wait for him to recover to go after Vanger. To be honest, he’d just slow her down.

The girl who laid down and died

Here’s how original this concept is. In the 1996 movie “12 Monkeys,” directed by the unconventional Terry Gilliam, Bruce Willis plays a man from a dystopian future sent back to attain an apocalyptic virus in its pure form so an antidote can be made; Madeline Stowe plays the 1990s psychiatrist who initially thinks he’s crazy but realizes he’s telling the truth. Her world will end and almost everyone she knows will die. And they’re chasing the bad guy through the airport when Willis is shot by airport security. What does she do? Does she go after the bad guy who has the virus that will kill five billion people, including probably herself? No. She cries, kneels beside the man, and cradles his dying head in her arms. When the man dies, all movement dies with him—even with the fate of the world at stake.

Barely anyone said shit about this idiocy. It seemed natural to them. Hero falls, girl falls with him. That’s the way of movies.

Here’s what I imagine Lisbeth would say: “Madeline Fucking Stowe.” Here’s what I imagine Lisbeth would say to the movie industry, who perpetuate this kind of storyline: “Fuck you, you fucking fucks.”

So I was worried how Hollywood would handle this aspect of the story. Obviously director David Fincher makes daring movies, but the actor now playing Mikael Blomkvist, Daniel Craig, happens to be the latest James Bond, the ultimate action hero, who rescues women and saves the world. That’s his job. Is it allowable, culturally or legally, to have the current James Bond rescued by a mere wisp of a girl who then tracks down the killer on her own? Because he’d just slow her down?

The girl who does the tattooing

Fincher’s version of “Dragon Tattoo” is like a speed-reader’s version of the Swedish version and it still clocks in at more than two and a half hours; but it’s an improvement in many ways. It gives us a better sense of Lisbeth’s inner life, as well as a better sense of her relationship with Blomkvist and why she becomes distant in the sequels. It also doesn’t stick Harriet Vanger out in the Australian outback; it sticks her right under our noses.

Plus David Fincher’s signature gloom is all over it.

The novel is difficult to adapt cinematically because it really begins with three storylines:

- Swedish industrialist Henrik Vanger (Christopher Plummer) is taunted by the murderer of his beloved niece, Harriet, 40 years after her disappearance.

- Journalist Mikael Blomkvist (Craig) loses a libel suit brought by an industrialist.

- Computer hacker Lisbeth Salander (Rooney Mara) loses her longtime legal guardian for one who demands sexual favors.

The connections between the storylines are initially tangential at best. Vanger investigates Blomkvist, via Salander and her computer-hacking skills, before hiring him to look into the disappearance of Harriet. Then, for almost an hour, Blomkvist and Salander follow separate paths. He traipses about in the cold of the Vangers’ various estates on their private island in Hedestad, digging into the past and searching for Harriet’s killer, while she deals with her new legal guardian, Bjurman (Yorick van Wageningen, the bad uncle of “Winter in Wartime”), a fat man who demands oral sex before allowing her access to her own money. When her computer is destroyed in an attempted subway robbery and she needs to buy a new one, he invites her to his home where he incapacitates her, ties her up and rapes her.

This is another scene I worried about in translation. The Swedish version is pretty graphic. And while the director of “Se7en” can obviously get pretty graphic, I wasn’t surprised, after the drugging and the tying up, that the camera began to pan out of the bedroom and down the narrow hallway, away from the shutting bedroom door. Yes, I thought. Leave the horror to our imaginations.

Which is exactly when Fincher brings us back into the bedroom for the brutal rape scene.

Did it seem more horrific in the Swedish version? Because I wasn’t expecting it or because it was more horrific? I remember Lisbeth limping home afterwards. We’re disappointed in her, this tough, smart girl who allows herself to get into that situation—until she reveals the camera in her bag and acts out her exquisite revenge. Fincher doesn’t give us the limping home; he reveals the awkward moments immediately after the rape. They’re in Bjurman’s place, after all. He has to untie her, after all. We see him slumped in the kitchen nook with something like guilt in his posture. “I’ll drive you home,” he offers, pathetically. When she slams the door, he thinks he’s gotten away with it.

I wonder what Bjurman thinks when Lisbeth calls and agrees to return to his place for more money. That she’s desperate? An addict? That she liked what he did? That his perversion fits into hers? Instead, he’s tasered, tied up, stripped and sodomized. He’s forced to watch a video of the initial rape and threatened with its internet upload if anything ever happens to her. Finally, she tattoos the following on his chest: I AM A RAPIST PIG. “Lie still,” she says, getting out the needle and promising blood. “I’ve never done this before.”

It’s the tattooing that makes the moment indelible. Up until then, her logic is Old Testament: an eye for an eye. But tattooing him adds something. The movie is about awful people who hide in plain sight, and Lisbeth is making sure they don’t hide too well. She’s handing out nametags. She’s branding scarlet letters.

The girl who is offered a purpose in life

What to make of the Vanger family tree? It’s a backstory better suited to novels. Henrik’s brother, Harald, is a Nazi who still lives in Hedestad, as does his daughter Celia (Geraldine James), while another daughter, Anita (Jolie Richardson), lives in London. Harriet’s father, Gottfried, also a Nazi, died the year before Harriet went missing, while Harriet’s brother, Martin (Stellan Skarsgård), now runs the company. “I’m quickly losing track of who’s who here,” Blomkvist says. Amen.

Of this crew, Martin is the one we see most often, and who’s played by the best-known actor, and who seems a decent sort. Which means, of course ... There’s a dinner over at his place with Celia and Blomkvist, and it’s one of the few moments where the harsh, Northern lighting of Sweden, which Fincher revels in, gives way to a softer, warmer lighting. It feels almost cozy in Vanger’s place—particularly with the harsh weather outside. One can even hear the wind howl. Or cry? Like a distant scream? It’s a subtle bit but people who know the story know it’s not the wind.

Blomkvist does well digging into a 40-year-old, missing persons case. The day Harriet disappeared there was a parade in town, and there’s a picture for the local newspaper of Harriet in the crowd. Blomkvist goes to the paper, retrieves the rest of the photos, digitalizes them, and creates a crude film in which it’s apparent that Harriet sees something, or someone, that stuns her. Another girl is taking her own photos behind Harriet. Might she have taken a shot of what Harriet saw?

The old inspector on the case is still alive. He tells Blomkvist that Harriet’s case is his “Rebecca case,” which is an unsolved murder case. There are several of those. There’s also a list of names and numbers written in the back of Harriet’s Bible: “Magda 32016” and “BJ 32027” and the like. Eventually the web becomes wide enough that Blomkvist feels the need for a research assistant.

Two reaction shots from this movie stay with me. When the Vanger family lawyer, Dirch Frode (Steven Berkoff), suggests to Blomkvist that they hire the girl who did the background check on him, Blomkvist responds, “The what?,” with a mixture of surprise and annoyance. He’s used to being the investigator, not the investigated. That’s the first one. Then when Blomkvist goes to recruit the girl, which finally brings our disparate storylines together, Lisbeth is wary of him until he says the line: “I want you to help me catch a killer of women.” Her reaction isn’t the blank one in the Swedish version. It’s the look of someone who is finally offered a purpose in life.

The girl who can hack into your soul

Now that I think about it, there’s a third reaction shot I love. It’s earlier in the movie. Lisbeth is meeting her boss, Armanasky (Goran Visnjic), and Frode, in a conference room in a corporate high-rise, where her mohawk, tats, boots and attitude don’t begin to fit. She asks, without worry, sitting at the other end of the long, gleaming conference table, if something was wrong with her initial report on Blomkvist. There wasn’t. They just want to know if there was anything she chose not to include. She turns away, offering her profile, and that great swoop of a mohawk, before adding, “He’s had a long-standing sexual relationship with the co-editor of his magazine.” Pause. “Sometimes he performs cunnilingus on her.” Pause. “Not often enough, in my opinion.” By now she’s staring back at them, chewing her gum, gauging their reaction. Frode, a proper gentleman, looks away. “No,” he admits, “you were right not to include that.”

This raises a point. Once they see how good Lisbeth is, why don’t they just hire her as their investigator? Remove the middleman by hiring the middleman. As good as Blomkvist is, he’s still 20th-century: forced, like all of us, to rely upon interview and instinct to uncover the truth. Lisbeth is 21st century. She can hack into your computer and see your soul. I love the bit where Blomkvist attempts to show her something on his computer, and her impatience with his tentative movements is palpable. It’s all she can do not to grab the mouse and drive.

As for how Hollywood handles the golf-club scene? The breadth of the investigation forces hero and heroine to split up—a trope that, in thrillers, usually plays to the detriment of the heroine. Not here. Alone in Martin’s house, Blomkvist figures out Martin is the longtime serial killer just as Martin comes home. But he manages to get out of the house. Then Martin sees him and calls out to him and invites him in for a drink. Later, when he has a gun on him, when he’s about to torture and kill him, he asks why he accepted the offer, knowing what he knows, then answers his own question. “The fear of offending is stronger than the fear of pain,” he says, amused by human nature. He taunts him about Lisbeth: “I like that one. I can’t thank you enough for bringing her to me.” He’s in the process of suffocating Blomkvist when Lisbeth arrives, swings the nearest weapon, a golf club, and takes off half of Vanger’s face. Vanger flees and Lisbeth attends to Blomkvist for a second before asking a kind of permission: “May I kill him?” she asks. I forget if she waits for a response. Probably not. It would just slow her down.

The girl who rides off into the sunset

Was it worth it? Making this U.S. version so soon after the Swedish version? Fincher’s a better director, no doubt, and the acting is a little better. The script is tighter but misses the creepier elements of the serial-killer investigation. The bit with the cat is a good addition, but... I don’t quite see the point, to be honest. Other than to get Americans, who don’t read subtitles, to see the fucking thing.

As for what happened to Harriet Vanger? It’s not Martin. When he had the upper hand, he confessed to everything but not that. So there’s more unraveling to do, another half hour, really, and Fincher almost, almost, goes the route the novel went. When Harriet turns up alive—in Australia in the Swedish version, in London under her cousin’s name in the U.S. version—and we realize that she did this to save herself from her awful, abusive brother, my reaction was something like disappointment. Wait, I thought. She knew what her brother was and yet let him do what he did for 40 years?

That, it turns out, is Lisbeth’s reaction in the book:

“Bitch,” she said.

“Who?”

“Harriet Fucking Vanger. If she had done something in 1966, Martin Vanger couldn’t have kept killing and raping for thirty-seven years.”

The Swedish version ignored these lines—they didn’t want to disturb the happy reunion between Henrik and Harriet—while Fincher merely alludes to them. “Harriet Fucking Vanger,” Lisbeth says at one point. But she doesn’t go further. Too bad. That’s key to me. Harriet Vanger is pretty but passive. She warns no one, passes out no nametags. She’s no hero. Most heroes, our stories tell us, are men. Most heroes, our stories tell us, save the day and ride off alone in the end.

One out of two.

—January 29, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard