Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

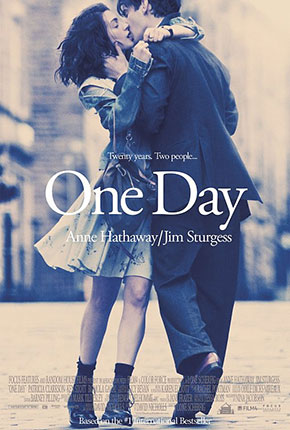

One Day (2011)

WARNING: A SPOILER A DAY

“One Day” is a gimmicky little film that doesn’t deliver. It gives us one day a year for 20 years in the lives of Emma (Anne Hathaway), a smart, mousy girl who loves Dexter, and Dexter (Jim Sturgess), an attractive, outgoing, shallow lad who ‘s too busy sowing wild oats to get serious about Emma. That’s the film’s main conflict: When will they get together? This year? Next?

The day in question is always July 15th, or St. Swithin’s Day in Britain, which is famous because of the following traditional verse:

St. Swithin's day if thou dost rain

For forty days it will remain

St. Swithin's day if thou be fair

For forty days 'twill rain nae mair.

I knew about the day mostly because of the Billy Bragg song, and because it sounds so fantastically British: Swithin’s. According to a quick online search, St. Swithin was “a Saxon Bishop of Winchester. He was born in the kingdom of Wessex and educated in its capital, Winchester. He was famous for charitable gifts and building churches.”

So is the movie about building churches? No. Is it about the weather? Not so much. Does it have anything to do with Billy Bragg’s song of lost love?

The Polaroids that hold us together

Will surely fade away

Like the love we spoke of forever

On St. Swithin's Day.

Sort of. But the movie fudges things in the manner of movies about love.

It begins chronologically in the late 1980s with the graduation of Emma and Dexter from college. Each has grand plans. She’s moving to London to write a book. He’s going to France to... I forget what. Learn about other cultures and then forget them.

In London, Emma winds up working long hours in a cheesey Mexican restaurant and getting nowhere with her writing and feeling defeated. Eventually she becomes a teacher involved with the wrong guy, Ian (Rafe Spall), a drab fellow who wants to be a stand-up comedian even though nothing he says is remotely funny.

Dexter winds up breezing through life. Before we know it, he’s the host of a loud, shallow TV show aimed at loud, shallow twentysomethings who like clubbing and video games. His dying mother (Patricia Clarkson) is appalled that he’s wasting his talents and his time in this manner. His father (Ken Stott) is merely appalled. He feels his son is drinking too much and not spending enough time with his dying mother. We’re supposed to take the father’s side in this, but the structure of the film, the one-day-per-year template, doesn’t allow for much emotional involvement. The father harangues the son for drinking before we even realize he’s drunk, for example.

Then fortunes change. Emma breaks it off with Ian, writes a book, it’s popular, and she moves to Paris and meets a gorgeous Parisian man. Dexter gets married to a busty blonde, has a kid, but loses his job and can’t find another. His wife cheats on him with his best friend. He’s washed-up and gray at 30.

But Emma still takes him back. She ditches Frenchy for him. True love.

With the central tension of the film thus resolved, other tensions need to emerge. They do. Year by year, Emma: 1) wants a kid; 2) still hasn’t had a kid; 3) dies in a biking accident. All on St. Swithin’s Day.

Afterwards, director Lone Scherfig (“An Education”) and writer David Nicholls (from his novel) do a good call-back to that first St. Swithin’s Day, in the late 1980s, and to a moment where the relationship could’ve deepened immediately but didn’t. There’s a sadness to it, certainly, this early scene, but it’s not the sadness of the Billy Bragg song. Bragg’s sadness is about how love, which we claim to be forever, fades. In “One Day,” love is forever. So the sadness of the callback, and of the movie, relates to the earlier, shallow choices Dexter made with his life and his loves. It’s about all that time wasted.

I would argue that the sadness of a true “One Day,” a better “One Day,” is that regardless of what we do with time, whether we “waste” it like the grasshopper (Dexter), or “make proper use of it” like the ant (Emma), it keeps going. It takes us with it until one of us is gone and the other is mourning, then both of us are gone and our survivors are mourning, then both of us are long-gone and there’s no one left to mourn. It takes us from a place where we have so many possibilities to where we have one: to die.

Love the poster, though.

—February 12, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard