Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

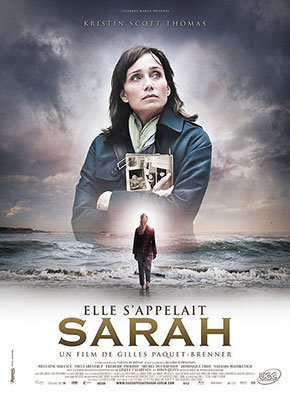

Sarah’s Key (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS IN THE CLOSET

“Sarah’s Key” is half of a great movie.

The first hour details the horrors of holocaust better than recent films such as “City of Life and Death” and “John Rabe,” both about the Rape of Nanjing, or “Le rafle,” a French film about the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup of Jews by the occupied French, and for the Nazis, in 1942. Those films tend toward melodrama. Here’s what I wrote about “Le rafle.”:

What is it with these recent movies about the horrors of World War II anyway? Why do we need to milk tragedy this way? Why is it not enough that Jewish mothers and children are stuffed into cattle cars bound for Poland? Do we need to intercut to the sympathetic, feverish nurse, biking to the train station on her last legs, on the hope that ... what? What if she got there in time? What could she do? Who would she stop? The French police? The Nazis? History? Yet the intercutting continues in order to heighten the drama. Or melodrama.

“Sarah’s Key,” based upon a novel by Tatiana de Rosnay, and also about the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup, is, for the most part, blunter and starker. On July 16, 1942, two kids are playing under the sheets in their bedroom while their mother (Natasha Mashkevich, reminiscent of Diane Kruger in her beauty) smiles and does needlework. Then the knock on the door. The French official. All Jews are being rounded up. Schnell schnell! Apologies: Vite vite! The girl, Sarah Starzynski (an astonishing Mélusine Mayance), is a quick study and hides her baby brother Michel in a near-invisible bedroom closet and locks the door. She tells him not to make any noise; she promises to come back for him.

But if you know anything about the roundup you know there’s no coming back. The Jews were taken to the Vélodrome d'Hiver near the Eiffel Tower in Paris for several days; then they were transported by train to the Drancy internment camp; then most of them were sent to Auschwitz.

So the first half of the movie is driven by this question: Can Sarah, or someone in her family, escape and make it back in time to free Michel? That’s the key, or the palpable key, of the title. Sarah keeps gripping that key in her sweaty little hand. She holds onto it for dear life—the life of her brother, whom she promised to return for.

Intercut with this 1942 storyline is a contemporary one, featuring Julia Jarmond (Kristin Scott Thomas), an American journalist for a dying international magazine, who is finally writing that in-depth piece on the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup she always wanted to write. She and her husband, Bertrand Tezac (Frédéric Pierrot), and their teenaged daughter, are also moving into his parents’ old place in the Marais district. Then she discovers she’s pregnant. Then she discovers that the Tezacs moved into their place in August 1942—a month after Vel’ d’Hiv—and that it originally belonged to the Starzynskis, whom she researches. So how culpable are her in-laws in the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup? How culpable is she?

From her father-in-law, who was a boy at the time Sarah finally returned, she learns the full story. We’ve already watched Sarah survive Vel’ d’Hiv and Drancy—where she is separated from her father and mother—then overcome a three-day fever and escape the camp with a companion, who succumbs to her own fever in a small French town; and with each event, Sarah’s increasing panic becomes our own. We try to add up the time. A three-day fever? Weren’t they already at the velodrome for several days? Plus Drancy. Has it been a week yet? Longer? How long can a boy survive without food and water?

As a result, the primary horrors of “La ronde.,” which are milked unnecessarily, are here almost secondary horrors. Yeah yeah, there goes the father. Yeah yeah, mother and daughter being torn apart by French officials at Drancy. But what about Michel?

Sarah convinces the old farmers who have sheltered her, Jules and Geneviève Dufaure (Niels Arestrup of “Un Prophete” and Dominique Frot, both powerfully understated), to travel with her to Paris to free her brother. By then the Tezacs have moved in, but she pushes past them, puts the key in the lock and opens the door. By which time, of course, there’s not much of her brother left to free.

As soon as we see, or see the reaction to, what happened to Michel (“We thought a bird had died in a gutter,” the father-in-law tells Julia. “We closed the windows but the smell only got worse”), I immediately thought: OK. We’re halfway through the movie. What’s going to drive it forward now?

Answer: Not much.

Julia, obsessed, keeps researching Sarah’s story: How she grew up, strong and beautiful but distant, on that farm; how she left without a word, in ’53; how she made it to America, and met a man, and married, and had a child, who grew up to be Aidan Quinn living in Florence, Italy, but how she died in an automobile accident back in ’67, which we suspect wasn’t an accident at all but a suicide, and which we discover, later in the movie, yes, we were right, it was a suicide.

The story of Michel is focused and intense while this is unfocused and uncompelling. The movie becomes less about Sarah, who’s mysterious to all who know her, including us, than about Julia, who is researching all this because... ? Who knows? Even she doesn’t know. It becomes soft and distant, with well-off people viewing tragedy in the rearview mirror and holding hands with sad smiles over dinner or drinks. It does a disservice to the child Sarah’s story by making the adult Sarah a stranger to us. One can understand her eventual suicide—how, even in America, with a new family, she couldn’t escape her horrifying past—but one still wonders who she tried to become. One wonders about the conversations she had in her head with her parents and her brother. One wonders if she felt she owed it to them to live or owed it to them to end her life. But we can only wonder because the movie keeps Sarah, as Sarah keeps the world, at a distance.

As a child, Sarah Starzynski holds onto her key at all costs. Unfortunately, writer-director Gilles Paquet-Brenner lets our key to Sarah slip away.

—August 8, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard