Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

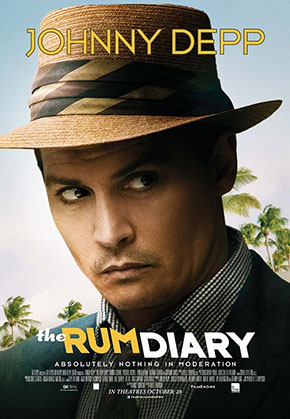

The Rum Diary (2011)

WARNING: 161 MINIATURE SPOILERS

“The Rum Diary” is a 2011 movie based upon a 1998 novel, which was actually written in the early 1960s, about misadventures in Puerto Rico in the late 1950s. It doesn’t have to be old news but it is.

It’s an odd version of old news. The lessons its protagonist learns are lessons its writer, Hunter S. Thompson, along with many others, communicated to the culture a long time ago. Druggies can be heroes and upstanding citizens can be villains. It’s us vs. the bastards, and the bastards are businessmen and bankers and land developers, shady and older and curiously sexless, while we, the heroes, or antiheroes, are young and aimless and vaguely anarchistic. We booze it up and experiment with drugs and lament the poor while trying to find ...something. Our artistic voice. Freedom. America. A girl.

If most movies present an absolutist vision from the right, with a taciturn hero taking on bad guys through direct violence and winning, the alternative version, the left-wing version popularized in the late 1960s, gives us an antihero, often glib, taking on dull but horrific institutional elements through subterfuge and losing. The very thing that Paul Kemp (Johnny Depp) needs to learn in "Rum Diary," in other words—bankers, etc., are bad—was communicated to the culture so long ago, by Kemp’s creator, that it became a genre unto itself: “Easy Rider” and “Animal House” and almost every B-movie from 1967 to 1982. So we wait for him to catch up. We wait for him to figure out what kind of movie he’s in.

It takes awhile.

Kemp may arrive in Puerto Rico in 1960 unformed in Hunter S. Thompson’s politics but we first see him in the classic Hunter S. Thompson pose: waking up, in a hotel room overlooking the beach in San Juan, dazed and hungover and horrified, unable to recollect who knows what godawful escapades from the night before. He’s there for a job, at the San Juan Star, because his two novels never caught on—either with publishers, or, in the end, with Kemp himself. Later in the movie he’ll talk about writers he admires. He’ll quote a line from Coleridge and talk about how the poet wrote it when he was only 25; he’ll talk about the difficulty of finding his own voice. The movie is the story of how Kemp, and by extension Thompson, finds his own voice.

He wants to write meaningful articles but his toupee-wearing editor, Lotterman (Richard Jenkins), isn’t interested. He assigns him horoscopes, and pieces about the bowling alleys of San Juan, frequented by the dull and overweight middle class of middle America, and Kemp’s mind wanders. He finds a beautiful girl, Chenault (Amber Heard), but she’s engaged to a jerk, Sanderson (Aaron Eckhart), who wants Kemp, of all people, to write marketing copy for land development on a nearby uninhabited island. They plan to wreck paradise again. Kemp goes along for the ride, signing an NDA and everything, but mostly he’s sniffing after Chenault. He doesn’t reject Sanderson until Sanderson rejects him. He finds religion because he’s cast out of Eden.

Did we need narration in this thing? Once Kemp finds his voice, we get noteworthy lines, presumably culled from the novel, such as: “I discovered the connection between starving children scavenging for food and the shiny brass plates on the front doors of banks.” We could’ve used such language throughout. The movie would’ve benefited.

Depp is obviously a great actor. “How does anyone drink 161 miniatures?” Lotterman demands when he gets Kemp’s hotel bill. There’s a pause, a few blinks, a slight wobble. “Are they not complimentary?” he finally responds.

But he’s too old. Sorry. Kemp is supposed to be unformed and learning. He’s supposed to be 22. Depp is nearly 50. He should’ve been playing Lotterman.

I actually identified with Lotterman. The movie doesn’t. It hates him. He’s on the side of the establishment. He’s old and toupee-wearing and soul-crushing. He makes sure that nothing really noteworthy gets in his paper. Except, I kept thinking, it’s not his newspaper, is it? He’s just the editor. He’s a higher-up flunky. Maybe I’m projecting, maybe Richard Jenkins added a humanity at odds with his character (see: Philip Seymour Hoffman in “Patch Adams”), but I get the feeling Lotterman would’ve liked the San Juan Star to be more than articles about bowling alleys and horoscopes. He would’ve liked to have had hair. He would’ve liked to be as handsome as Johnny Depp. Who wouldn’t? But that wasn’t his world.

Instead, the movie has sympathy for the worthless and vaguely fascistic Moberg (Giovanni Ribisi), who also works at the San Juan Star but who rarely contributes copy. He spends his days in a drug-addled stupor, stumbling from spot to spot, and occasionally putting on an LP of speeches by Adolf Hitler. Riotous, dude.

To be honest, “Rum Diary” reminded me of all I disliked about those cinematic, absolutist visions of the left: the celebration of drugs and anarchy. We get that damned quote of Oscar Wilde’s for the zillionth time: “Nowadays, people know the price of everything and the value of nothing.” We get Depp as Kemp as Thompson writing his credo:

“I want to make a promise to you, the reader. And I don't know if I can fulfill it tomorrow, or even the day after that. But I put the bastards of this world on notice that I do not have their best interests at heart. I will try and speak for my reader. That is my promise. And it will be a voice made of ink and rage.”

It’s tiresome. Putting hallucinogens in your eyes isn’t a political act, it’s a stupid act. The left never got that. They conflated the two. Watching “Rum Diary,” I thought of the sadness of the political arc I’ve lived through. Kemp is working toward a credo, an ethos, a style, that dominated our culture for a time but ultimately led to Reagan and Bush and Bush. He puts the bastards on notice but the bastards only got stronger.

—February 25, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard