Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

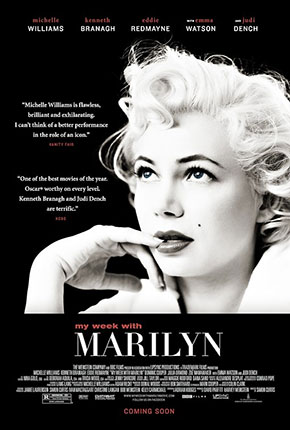

My Week with Marilyn (2011)

WARNING: THE PRINCE AND THE SPOILERS

We’re getting more of these, aren’t we? Let’s call them starstruck movies. They’re not “All About Eve” or “The Artist”—cautionary tales in which a star and an ingénue/flunky become rivals or switch places. No, here, as in “Funny People” in 2009 and “Me and Orson Welles” in 2010, the flunky never rises, and the relationship remains unequal, and eventually—with the exception of “Funny People,” which features a fictitious star—the star goes away, as stars always do. Stars are meant to be seen from a distance, not close up. One can get blinded that way. Why Colin Clark (Eddie Redmayne), the titular possessive in “My Week with Marilyn,” is always blinking his eyes, almost shielding them, in the presence of the titular object of his desire.

So what do we learn from these kinds of films? That the very famous are not like you and me. That they’re often horrible to you and me. But look, look at what they create. Isn’t it worth it? In the end?

Colin, a 23-year-old recent Oxford graduate from money and power, is enamored of the movies and decides he’s going to make it in the movie business “on his own.” So he loads up his sports car, drives to London, and, showing the persistence of a man who is too rich and powerful to have been beaten down by life, hangs around the offices of Laurence Olivier Productions until he’s given small tasks. When Laurence Olivier himself (Kenneth Branagh) shows up, he recognizes Colin, and directs the head of production, his flunky, to find Colin a job. Which is how Colin becomes a “third,” or third assistant director, or, more properly, gofer, on Olivier’s new film, “The Prince and the Showgirl” co-starring Marilyn Monroe (Michelle Williams).

This was Monroe’s serious actress phase. She was already the biggest movie star in the world, which is what she’d always wanted, but it wasn’t what she wanted. Now she wanted to be taken seriously. So she got married to a serious playwright, Arthur Miller (Dougray Scott), started a production company with a serious photographer, Milton Greene (Dominic Cooper), and studied method acting under the ultra-serious Paula Strasberg (Zoe Wanamaker), wife of Lee Strasberg, who ran the Actor’s Studio, where actors such as Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift were taught how to act seriously. Oh, and she decided to make a movie with Sir Laurence Olivier, generally regarded the greatest actor in the world.

Problem? Olivier is a classical actor, not method. And the movie they’re making together isn’t a serious film, it’s a light comedy.

Bigger problem? They don’t click.

He’s professional, she’s unprofessional. He’s impatient, she’s confused. He’s ready, she can’t read a line, even during a table read, without conferring with Paula Strasberg. During takes with Olivier and Dame Sybil Thorndike (Dame Judi Dench, who is, as always, delightful), she is forever forgetting her lines. Is she nervous? On drugs? Stupid? Distracted by Strasberg? Confused by method acting? All of the above? The movie never clarifies the issue. “Use your substitutions and make it work for you,” Paula tells her. “Just be sexy: Isn’t that what you do?” Olivier tells her.

When she begins to hole up in her dressing room, it’s young Colin who’s sent to fetch her; and it’s young Colin, with his innocent, starstruck face, to whom she begins to confide—even as the wall of people surrounding her and protecting her crumbles. Her publicist, Arthur Jacobs (Toby Jones), returns to the states. Her husband, with whom she fights, returns to the states. Who can she choose to help prop up the wall? “Are you spying on me?” she asks Colin at one point. “Whose side are you on?” she asks him at another point. His answer, after a momentary pause, is the one she wants to hear: “Yours, Miss Monroe.”

Off they go. He shows her Oxford (or is it Eton?) and the delighted schoolboys surround her. They visit his godfather, Sir Owen Morshead (Derek Jacobi), the official librarian at Buckingham Palace, and she asks silly, Monroe-esque questions. They have a picnic near a stream and they wind up semi-skinny-dipping. In the water, she kisses him and he looks on, amazed, as if he’s watching it all rather than participating in it. One night she has a breakdown, asks for him, and they wind up spooning in her bed, clothed. He wakes to find her taking a bubble bath and acting coquettish. Acting like Marilyn Monroe.

It’s like a dream—almost literally. I used to write down my dreams, and this is one I had nearly 20 years ago about one of Marilyn’s many would-be replacements:

Madonna came to town. I was supposed to greet her. I was her greeter? She was over at my father's house partially undressed and we made out on the couch. I was worried about her because she seemed so unstable and sad. I wanted to sleep with her but I needed to protect her.

That’s Colin’s dilemma, too. In a sense it’s every man’s dilemma (the battle between protect and fuck) but the movie doesn’t do much with it. The movie doesn’t do much with him. Does he remain the Olivierian professional or side with Marilyn? Does he protect her or sleep with her? Can he protect her while sleeping with her? He’s in nearly every scene but we get no sense of his inner life. Is there no roar there? She wants to pretend they’re 13-year-olds on a date. What does he want to pretend?

Worse, the movie thinks it’s presenting a version of Marilyn we haven’t seen before when it’s the Marilyn we’ve seen all too often before: screwed-up and pill-popping and user and used. It focuses on Marilyn, the star, versus Norman Jean, the lost little girl, as if this dichotomy is new. “Shall I be her?” she says at Buckingham Palace. “I’m not her,” she confides to Colin. “As soon as people see I’m not her, they run,” she says. Yet, even in private, she keeps acting like “her.”

“My Week with Marilyn” isn’t a bad movie but it’s not a particularly interesting one. He’s not that interesting, she’s not that interesting, and, in the process, a not very interesting movie gets made. Oh, but look at her light up the screen, Olivier says after all that trouble. Just look. He’s amazed. The movie is amazed. In the end, the movie is as starstruck about Monroe as Colin.

—December 30, 2011

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard