Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

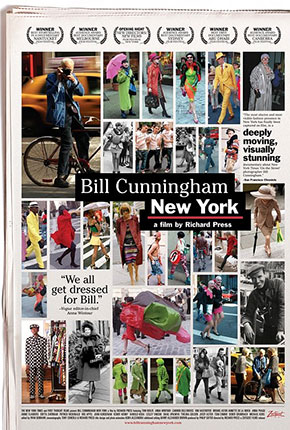

Bill Cunningham New York (2011)

WARNING: MARVELOUS, EXOTIC SPOILERS OF PARADISE

“He who seeks beauty will find it.”

Bill Cunningham, quotidian fashion photographer for The New York Times, says this near the end of Richard Press’ excellent, moving documentary, “Bill Cunningham New York,” while accepting an award from the National Order of the Legion of Honour of France; and it’s so true to him, so meaningful to him—and, really, to the documentary about him—that his voice begins to crack. He’s not just espousing something he read. He’s telling us his life philosophy. The point of what he does, he says, is “not the celebrity, and not the spectacle. It’s as true today as it ever was: He who seeks beauty will find it.” Then he thanks the French and leaves the stage.

Cunningham is an American original. He covers the tux-and-gown society scene for The New York Times on a Schwinn bicycle. He covers the haut couture fashion shows wearing the sturdy blue jackets of French street cleaners. He is one of the better known fashion photographers in the country even though he’s the first to admit he’s not really a fashion photographer. He has an overwhelming joie de vivre that covers an overwhelming personal sadness.

His “On the Street” column is an American original. Screw the models; screw high society; what are the people wearing?

“The best fashion show is definitely on the streets,” he tells us early in the doc. “Always has been and always will be.”

What trends are forming? What’s interesting? What’s fun? Who’s fun? What “marvelous, exotic bird of paradise,” as he calls them, might he spot today? His frequent subjects include: Iris Apfel, the nonagenarian teenager wearing her great, round glasses; Patrick McDonald, the carefully chapeaued and eyelined dandy; and Shail Upadhya, the former U.N. official from Nepal, whose loud, colorful, homemade suits are at humorous odds with his dour visage.

“You’ve just got to stay out there and see what it is,” says Cunningham. “You’ve got to stay on the street and let the street tell you what it is. There are no shortcuts, believe me.”

A gentleman in the age of snark

Cunningham is in his early 80s, and so, despite his pep—and he’s someone who actually deserves that word—there’s something inevitably old school about him. He still uses film in the digital age, for example. He’s also a gentleman in the age of snark.

“He’s incredibly kind,” says socialite Annette de la Renta. “I don’t think we’ve ever seen a cruel picture done by Bill. And he’s certainly had the opportunity.”

Back in the day, and for a time, Cunningham wrote a millinery column for Women’s Wear Daily. Then he wrote a piece, similar to what he does now, on women in the street wearing the clothes of the models of the runway. It was a positive piece about style: how each woman made the fashion her own.

“And they changed his copy to make fun of the women,” says Annie Flanders, founding editor of Details magazine. “He didn’t think he’d ever get over it, because he was so embarrassed and upset. ... That was the end of his career at Women’s Wear Daily.”

Tellingly, Cunningham doesn’t say a word on the subject. He’s someone who focuses on the positive: the fashion he likes and the stories he likes.

Who’s that boy?

So who is he? Where does he live? Is he from an upper-class family? Is that why he fits in so well with socialites? Is he straight? Gay? Why is someone so passionately interested in fashion so disinterested in fashion for himself?

“People don’t get to know him very well, do they?” asks Iris Apfel. “I get the feeling he doesn’t sit down and talk to people very much.”

“I have no idea of his private life,” says Annette de la Renta. “I have no idea if he’s lonely.”

Answers come by and by. He lives at Carnegie Hall, of all New York places, in a room so cluttered, so full of file cabinets and old magazines, it could be used to torture claustrophobes. Part of the drama of the doc is that Cunningham, and the few remaining artists living there, are being evicted by the grandees of Carnegie Hall. By doc’s end, he’s in an apartment overlooking Central Park. We should all be so displaced.

His background is working class. That helps explain the blue jacket and the taped poncho, and the egg sandwich and coffee lunches, but Women’s Wear Daily also helps explain these things. If you spend less, you need less, and you need to work less with folks whose purpose is the opposite of yours. That torn poncho, looking almost like a garbage bag, which he happily fixes with electrician’s tape, is a kind of freedom.

So: a fascinating man. A good documentary. Then, in the last 10 minutes, it becomes a great documentary.

The patron saint of unspecified sorrows

Press, the documentarian, gets Cunningham to do what Iris Apfel suggested he doesn’t do. He sits him down and asks him questions. He says has two very personal questions for him, which Cunningham may or may not want to answer. He says it’s up to him.

First: Have you ever had a romantic relationship in your entire life?

Cunningham, elfin and buoyant as usual, laughs at the question and answers it with one of his own: “Now do you want to know if I’m gay?” Then he answers it—his own question—but elliptically, with a callback to his working-class family, and how they most likely discouraged him from entering the fashion world for that very reason. Because they suspected. Even if he didn’t. Not then.

When he gets back to the romantic relationship question, he answers in the negative. “There was no time,” he says, his smile now strained. “I was working night and day. In my family, things like that were never discussed.”

His answers simply bring up more questions. Was his work a means to ignore, or cover up, what he didn’t want to face? Early in the doc, Cunningham calls fashion “the armor to survive everyday life.” Is that what his camera, and his work, is for him? A means of staying on the sidelines and not getting in the game?

Press’ second personal question isn’t a question at all. It’s a pretty innocuous statement. But it releases the deluge.

“I know you go to church every Sunday,” Press says.

“Oh yeah,” Cunningham answers. Then he bows his head, and his shoulders begin to shake, and a second later one realizes he’s crying. He sobs for 10 to 15 seconds. Then he lifts his head and answers. He seems to be clarifying things for himself as much as for Press:

Yeah, I think it’s a good guidance in your life. Yeah, it’s something I need. Yeah, I guess maybe it’s part of your upbringing, I don’t know. Whatever it is. Everyone... You do whatever it is you do as best you... Yeah, I find it very important. For whatever reason. I don’t know. (Laughs) As a kid, when I went to church, all I did was look at women’s hats. (Serious again, nodding.) But later, when you mature, for different reasons.

In the very next scene, his colleagues at The New York Times celebrate his birthday by wearing Bill Cunningham masks (photos of his face attached to sticks), but it’s in this scene where his mask slips, and a huge pool of sorrow is revealed, and we’re not quite sure what to make of it. What is the sorrow? What are the different reasons he goes to church? It seems mixed up with the usual: love and family and sex and relationships and loneliness and work and faith, and the things we try to leave behind but which stay with us, and the things we hope will eventually catch up with us but never do.

We never find out. I think this makes the doc better. Up to this point, Cunningham is admirable. He’s a professional and an original and a gentleman: someone who set out to do what he wanted and is still doing it on his own terms. Once he breaks down, he becomes us. Because we all have our pools of sorrow. We all have questions that might release a deluge. It’s part of the reason why, like Bill Cunningham, patron saint of specific joys and unspecified sorrows, we go out, every day, and seek beauty.

—March 7, 2012

© 2012 Erik Lundegaard