Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

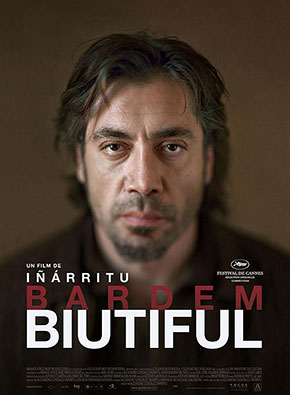

Biutiful (2010)

WARNING: THE ROAD TO HELL IS PAVED WITH GOOD SPOILERS

The world of Alejandro González Iñárritu (“21 Grams,” “Babel”) tends to be a polyglot of crowded, marginal characters. It’s a world where everyone ekes a living off of each other, and what light there is is fluorescent. Halfway through his latest, “Biutiful,” the sun shines on a family eating breakfast together. “Ah, the sun,” I thought. Then it goes away. The sun is for other people’s movies.

Iñárritu is all about border crossings. At the start of “Biutiful,” Uxbal (Javier Bardem) is facilitating between two immigrant groups, the illegal Chinese and the legal African, in Barcelona. The former make bootleg products in basement factories, which the latter then sell along Las Ramblas or in the Plaza Cataluña. Uxbal bribes la policia to look the other way.

He’s also clairvoyant. Did I mention that? He can communicate with the recently dead and help them cross that final border to the undiscovered country from which no traveler returns. I should add that never has such a gift been presented in such by-the-way fashion in a movie. Uxbal has an answer to the most profound question in human history—does the individual consciousness survive death?—and he views it like it’s pro bono work, like it’s a hobby. He does it on the side when he has the time.

Despite this gift, Uxbal’s life is no great shakes. He lives in a cramped, basement apartment with his two kids. His ex-wife, Marambra (Maricel Alvarez), is bipolar, an addict, and sleeping with his brother. He’s really only a step or two up from the immigrants he’s helping or exploiting. Then he’s diagnosed with cancer and given months to live.

So is this going to be that kind of story? The inconsequential man, forced, by the proximity and sudden inevitability of death, to see the beauty of life? Yes, there’s some of that. Uxbal is a hulking, glowering figure for much of the first third of the film. (You realize what a powerful back, and what a huge head, Bardem has.) After his diagnosis, he softens a bit. He visits his clairvoyant mentor, who tells him, “Put your affairs in order.” Both she and he know that the biggest problem for the recently dead is worry over unresolved matters, which get them to linger, to remain where they shouldn’t, and neither wants that for Uxbal.

So Uxbal begins to put his affairs in order. He tries to help the Africans, who are being deported for selling drugs. He tries to help the illegal Chinese immigrants, who live in horrible conditions, by buying them space heaters. He reconnects with Marambra, who still loves him, and he and the kids move into her apartment. They have breakfast together. The sun shines through the window. Life is good.

But life, as short as it is, lasts longer than “good.” The Africans are deported despite Uxbal’s efforts. Marambra goes back to partying, and doing drugs, and she beats the youngest, Mateo (Guillermo Estrella), forcing Uxbal to move everyone back into his basement apartment, which he’s already given to Ige (Diaryatou Daff), the wife of one of his deported Africans.

Most horrific: the heaters Uxbal buys for the Chinese immigrants—made, no doubt, by people under conditions similar to theirs—don’t work properly. Iñárritu telegraphs the moment. Twice in the movie we see the Chinese foreman unlock the doors to wake the workers at 6:30 a.m., but both times we’re inside the room. The third time Iñárritu places the camera outside the room, over the foreman’s shoulder. The door opens and, lo and behold, dozens of dead bodies lying on the floor. Patricia, watching next to me, gasped in horror, but I was only surprised that it was an apparent gas leak. I was expecting charred bodies burnt to a crisp.

So now Uxbal has dozens of deaths on his conscience just as he’s dying himself. How does he deal with the weight of all this? Poorly or not at all. He makes a few motions, feints in several directions, but he’s really too busy dying to do anything proper. He withers, wears diapers, is confined to bed. Ige begins to watch his kids, to feed them. Will she be his savoir? On his deathbed, Uxbal gives her money to pay a year’s rent, so at least his kids will have a place to live for a year, but she uses the money to travel back to Africa and her husband. She abandons his for hers.

Every attempt to put his affairs in order, in other words, leads to chaos and heartbreak. It’s as if a sick God is foiling his every move. One is.

What is it about Iñárritu? He deals with themes I care about but his execution always bores me. His scenes are gritty but peculiarly weightless and airless. He shoves too many characters on the screen, shrinking them to make them all fit. He pisses me off.

I did like two scenes, however, shown both the beginning and end of the movie.

In the first scene, the camera focuses on two pairs of hands, male and female, and we hear voices, male and female, talking about a diamond ring. “Is it real?” she asks. Yes, he answers. She wants to wear it. He lets her. It could be a young couple, postcoital, at the beginning of their journey, but by the end of the movie we know it’s Uxbal and his daughter, Ana (Hanaa Bouchaib), and the conversation is the last he will have in this world.

In the second scene, Uxbal is in the woods eyeing a handsome young man. They smoke cigarettes and have an odd conversation about owls. The man, younger than Uxbal, shorter than Uxbal, seems the dominant one, while Uxbal has a kind of shy, flirtatious love shining in his eyes. Initially confusing, by the end of the movie we know the man is Uxbal’s father, who died when Uxbal was young, which means Uxbal is now dead. This is the afterlife. But it’s almost like a dream, isn’t it, pieced together from life in the way of dreams. Freud once observed that anything we hear in a dream we first hear in life, and so it is with the conversation about the owls. Initially it was Mateo’s conversation to Uxbal. The woods themselves seem culled from a refrigerator drawing of Mateo’s: childish woods beneath the word “biutiful.”

But this is only the beginning of death. In the woods, Uxbal’s father moves away, and Uxbal says “What’s over there?” He follows him. The camera stays behind. And that’s where the movie ends.

Patricia loved it. When the lights came up I looked over and her cheeks were soaked with tears. For a moment it made me question my own nonplussed reaction. But only for a moment.

Iñárritu is all about border crossings but his movies don’t inspire any border crossings in me. They don’t take me any place I haven’t been or want to go. I remain (stubbornly? frustratedly?) on this side, in the place I started.

—February 9, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard