Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

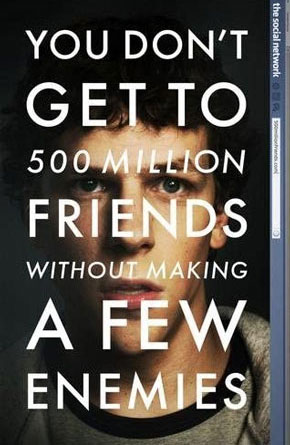

The Social Network (2010)

STATUS UPDATE: SPOILERS

There’s such a joy of intellect in Aaron Sorkin’s scripts that he’s almost unAmerican. He makes brains and articulation seem like a superpower. He makes them seem cool.

The people in his stories have so much to say that they can’t stop to say it; they have to keep moving. You could say Sorkin was made to write the script for “The Social Network,” the story of the founding of Facebook, because it, too, is about supersmart, superarticulate people who are perhaps so smart and so articulate that they speak before they should. This goes not only for the character of Marc Zuckerberg, played in an Oscar-nomination-worthy performance by Jesse Eisenberg, but also Larry Summers (Douglas Urbanski), the then-Harvard president, who, when confronted by the Facebook phenomenon, scoffs at this “million dollar idea.” And he should scoff. To quote Sean Parker (Justin Timberlake) channeling Dr. Evil later in the movie: It’s not a million dollar idea; it’s a billion dollar idea.

The movie begins with one of the best conversations I’ve heard in the movies (or anywhere) in a long time. Zuckerberg and his girlfriend, Erica Albright (Rooney Mara—the new Lisbeth Salander), talk around and through each other over beers at the Thirsty Scholar Pub at Harvard University in the fall of 2003. He brings up the topically relevant but factually doubtful factoid that there are more genius I.Q.s in China than there are I.Q.s in the U.S., while offhandedly bragging about his SAT scores (1600) and worrying over which Harvard “final club” (off-campus social club) he should pledge. She tells him he’s obsessed with final clubs, pronouncing them “finals clubs,” which he corrects. The deeper into the conversation, the more each says something that implies more than it says. She asks which final club is the easiest to get into (implying he needs “easy to get into”) and he says, when she pleads homework, that she doesn’t have to study because she goes to B.U. (Boston University: i.e., with the rest of the yokels). It’s amazing how dumb the smartest people are. She breaks up with him on the spot, then delivers the crushing blow. She tells him he’s going to go through life thinking girls don’t like him because he’s a nerd; but, really, they won’t like him because he’s an asshole.

Cue opening credits.

Wow. Now that’s my kind of open.

The bang-bang doesn’t stop. In his dorm room, he grabs a beer and blogs out his anger on livejournal.com. “She’s not a 34 C; she’s a 34 B—as in “Barely anything there.” There’s something quaint about the founder of Facebook using a site as pedestrian as livejournal.com. Although according to some measures, it’s still one of the top 100 sites on the Internet. Facebook? It’s no. 2. After Google.

On the same night, Zuckerberg gets an idea for rating the women of Harvard, hacks into dorm records to gets their photos, borrows an algorithm from his business-major friend, Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield—the new Spider-Man), and goes live. Within hours, and in the wee hours, there’s so much traffic it crashes the Harvard servers. There’s pride all over Zuckerberg’s face. Then a sense of ... oops.

He’s put on academic probation for six months, becomes even more of an outcast with women (“u dick,” one note reads), and gets the attention of some upperclassmen, the Winklevoss twins, Tyler and Cameron (both played by Armie Hammer), tall, strong, stars of the crew team, who recruit him to update their Web site concept harvardconnection.com, a place where Harvard students can meet each other online. But they make a couple of mistakes in the overture: 1) they only let him enter their club as far as the bike room, and b) they imply his reputation needs rehabilitation, even though it’s obviously that rep that drew them. So with seed money from Eduardo, he begins creating his own Web site where Harvard students can connect. He calls it “The Facebook.” When it goes live and proves remarkably addictive, the Winklevosses, or Winklevi as Zuckerberg calls them, are furious.

Throughout, scenes are juxtaposed with two future depositions: one brought by the Winklevosses, the other by Eduardo. In each, particularly the former, we get Zuckerberg’s stubborn insistence that he never stole any of their code. Where is their code? he repeats. It’s a legally bogus argument that reveals so much. To Zuckerberg, code is the only intellectual property—the only language, really—that matters.

So at this point, now that he’s got Facebook created, what’s the story? What’s “The Social Network” about?

Essentially it’s a love triangle: Zuckerberg and Eduardo are the lovers, or the partners anyway, and Timberlake’s Sean Parker, the founder of Napster, is l’homme fatal: the man who comes between them. At their initial meeting, he quickly (too quickly?) impresses the usually unimpressed Zuckerberg, while Eduardo’s face reveals a different emotion—one that most of us in this zippy, broadband world can relate to: the fear of being left behind.

Eduardo and Zuckerberg wind up clashing over what to do now that Facebook is taking off. For Eduardo the answer is easy: make money; sell ads. For Zuckerberg the answer is easy: let it become what it’s meant to become without the impairment of ads. The site has to be cool and ads aren’t cool.

Zuckerberg moves near Stanford (and Parker) for the summer, then for the following semester. Facebook expands to other Ivy League schools, then other schools across the country, then across the pond, and they’re doing it all on Eduardo’s original $19,000. But poor Eduardo is acting like a salesman now, a Willie Loman, pushing his product in Manhattan offices to people who just don’t get it. He’s being left behind.

More even than the Winklevosses, who have something sturdy and noble about them, Sorkin and director David Finch make Parker the villain here. At a hip, west-coast club, over a thumping beat, Parker tells Zuckerberg that his is a once-in-a-generation, holy shit idea, and adds, for confirmation, “Look at my face.” I had been looking at his face. In the hot lights of the club, it was glowing as red as the devil’s. Plus, for most of the movie, it’s a surprisingly unattractive face, seeing that it belongs to Justin Timberlake. It’s as if they gave the singer the flu so he could play the part.

Betrayals are made all around—first Eduardo, then possibly Parker—but how culpable is Zuckerberg? Is he truly that vindictive or is everyone else truly that paranoid? The longer the movie lasts the less we know him. That’s criticism of a sort. Throughout the depositions, Zuckerberg often asks questions of a pretty, two-year associate, Marylin Delpy (Rashida Jones), and she seems sympathetic to this boy genius, this solitary, disconnected man who connected the world, and offers, at the end, a comment that bookends Erica Albright’s at the beginning: “You’re not an asshole, Mark. You’re just trying hard to be one.” That, unfortunately, is one of the weaker lines of the movie. I don’t believe a two-year associate would say it under those circumstances. And I don’t believe it’s true. He is an asshole. That’s part of why he is where he is.

There are a couple of other moments that, at second glance, lose their luster. Sean Parker is introduced in a great scene in which he and a Stanford co-ed introduce themselves after a one-night stand. She accuses him of not knowing her name, but he does. Yet she doesn’t know his. Only after another half-minute of conversation does the other shoe drop. The Sean Parker? Of Napster? It’s a great intro, but, once we get to know him and his self-aggrandizing ways, it’s hard to picture him entering any party where he might meet such a co-ed without letting everyone know who he is.

There’s also the implication that Zuckerberg did all he did for Erica Albright, the girl who rejected him in the beginning. Many critics have already compared the film to “Citizen Kane”—less for form than content: the rise and fall of a scoundrel; the Xanadu loneliness; the betrayal of the last, best friend—but, in the scheme of things, a sophomore-year girlfriend is hardly a childhood sled. It reveals little that we don’t already know about the man. Or the boy.

My criticisms are mild, though. This is a smart, fun, relevant movie. The final scene, where Zuckerberg finds Erica on Facebook and sends her a friend request, then sits refreshing her page over and over again, is a scene for our time. This thing has been sent out into the ether and we need something to come back. We need to be filled, constantly filled, by the online world, because, for social animals, connecting online is like the thirsty drinking salt water. We keep doing it and it’s only making us thirstier.

—October 2, 2010

© 2010 Erik Lundegaard