Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

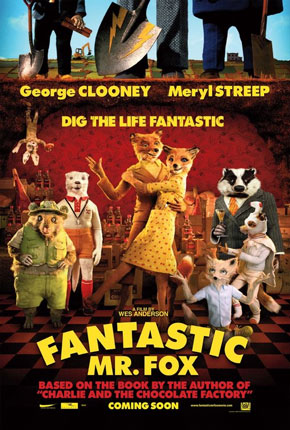

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009)

WARNING: CUSSIN’ SPOILERS

“Fantastic Mr. Fox” is a joy to watch because it’s both a Wes Anderson movie and a George Clooney vehicle.

Its Wes Andersonness is obvious. It gives us deadpan humor, father-son conflict, characters associated with one absurd and outdated mode of dress. It tosses up chapter titles (“The Go-For-Broke Mission”) and tosses in a tinkly soundtrack and bouncy-but-obscure, British-invasion-era music (“Let Her Dance” by Bobby Fuller Four). In 2007 I wrote the following about the essential Wes Anderson lesson: Exclusion isn’t necessarily the problem but inclusion is almost always the solution. That’s still true for his films—whether we’re talking Fischers, Tenenbaums, and Zissous or foxes, badgers, and weasels.

Where “Fox” differs from a typical Wes Anderson movie is in its hero. Anderson’s protagonists generally pretend to be something they’re not: great playwrights, great oceanographers, caring patriarchs. Eventually their true nature is revealed and they’re excluded from where they want to be. Only in returning, chastened and wiser, do they become the very thing they were pretending to be.

The movement for Mr. Fox (George Clooney) is the opposite. His persona is basically the George Clooney persona—the hyper-articulate, know-it-all whose charm resides in not always knowing it all but mustering through with grace and style anyway—and this persona, Mr. Fox’s persona, hardly changes during the course of the movie. For a time he denies his true nature, but he does so for others, not himself, and it’s a mere blip of screentime. It’s not the Anderson cycle of pretense/exclusion/genuineness. It’s the Clooney promise: Get on board, boys, we’re going for a ride!

The reason Mr. Fox is forced to deny his true nature is the reason many of us are forced to deny our true natures: he starts a family. One moment he and his wife are stealing squabs from a nearby farm, the next they’re trapped by a cage. Before they can escape, Mrs. Fox (Meryl Streep) announces she’s pregnant, and elicits a promise from Mr. Fox that he’ll settle down and never steal squabs and chickens and the like again.

Out of one trap and into another.

For two years (12 fox years, we’re told), Mr. Fox works as a newspaperman and lives with Mrs. Fox and their son, Ash (Jason Schwartzman), in a comfortable hole, until one day he says he’s tired of living in their comfortable hole. He’s got his eye on a tree that they can’t afford. Except he really wants the tree because of it overlooks Boggis, Bunce and Bean, three farms producing, in order, chickens, turkey and cider, and run by “three of the meanest, nastiest, ugliest farmers in the valley,” according to Fox’s lawyer, Badger (Bill Murray), who counsels against purchase. Fox ignores him. He tells himself he’s after one last job, by which he means three last jobs, one for each farm. For the first two he drags along Kylie, the passive, not-bright, handyman opossum (Wallace Wolodarsky), who is essentially the Pagoda of this film, and both jobs go off, give or take an electric fence, without a hitch.

For the final job, at Bean’s cider farm, Ash tries to tag along but is sent home; instead Fox relies on Ash’s cousin and rival, Kristofferson Silverfox (Eric Anderson), a meditating, martial-arts-training natural athlete who is staying with the family. Again, give or take a rat guard (Willem Dafoe), and the appearance of the very masculine-looking Mrs. Bean (Helen McCrory), the job goes off without a hitch. The problem: of the three nasty farmers, Bean (Michael Gambon, brilliant here) is the nastiest of the bunch. Also the smartest. And he organizes Boggis and Bunce into bringing the fight to Mr. Fox.

Thus begins a war of escalation. First they attempt to shoot Mr. Fox but succeed only in blowing off his tail (which Bean wears as a tie); then they destroy the Fox’s tree home with bulldozers (shades of “Avatar”!), but discover the Foxes have dug down to safety. When they try to dig them out, the Foxes simply dig deeper, and further, and eventually back into the Boggis, Bunce and Bean farms, from which they steal everything. By this time, other animals have been swept up in the war, and they all gather at a large underground dining table to celebrate. But just as Mr. Fox is delivering his toast of triumph, a rumble is heard. The rumble of cider. They’re being flooded out of their homes and into a sewer, from which there appears no escape.

But there is an escape. Earlier, when Mrs. Fox learned of her husband’s treachery, we got the following dialogue:

Mrs. Fox: Why did you lie to me?

Mr. Fox: Because I’m a wild animal.

Meanwhile, Ash, who likes to wear a cape, and who doesn’t even have a proper bandit mask but uses a reconstituted tube sock, is dealing with others’ perceptions, and his own perception, of his difference.

And that’s their salvation. They’re all wild animals and they’re all different. Mr. Fox, calling everyone by their Latin names (Oryctolagus Cuniculus! Talpa Europea!), uses the talents of each species for their final plan of attack, their final salvation. Exclusion isn’t necessarily the problem but inclusion is almost always the solution.

“Fantastic Mr. Fox” is delightful on many levels—it’s funny, quirky, tender, adventurous—but it resonates long after you leave the theater for the following reason. The convention of children’s stories is to have wild animals talk, wear clothes, and engage in human professions, and “Mr. Fox” certainly adopts those conventions. Then it upends them by having the wild animals realize the absurdity of not being what they are: wild animals. Wes Anderson, in other words, dresses up his animals as people so the people watching can realize that they, all the lawyers and high school coaches and newspapermen in the audience, are animals. All of us, in small ways, in the clothes we wear or the jobs we have, are denying our true natures. The joy of “Mr. Fox” is that Vulpes Volpes gets to reveal his true nature. The bittersweetness of Homo Sapiens is that, generally, we don’t.

—Fubruary 5, 2010

© 2010 Erik Lundegaard