Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

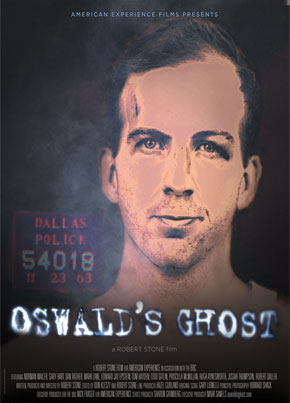

Oswald’s Ghost (2007)

WARNING: MAGIC SPOILERS

Norman Mailer gives us the title. “Oswald is the ghost that lays over American life,” he says, with the usual twinkle in his eye, near the end of this well-made documentary. “What is abominable and maddening about ghosts is you never know the answer. Is it this or is it that? You can’t know because the ghost isn’t telling you.”

Yet “Oswald’s Ghost” tells us plenty—because it’s less conspiracy theory, or conspiracy debunker, than conspiracy history. It takes us chronologically, and cleanly, through events, and delves into why we began to believe there was a cover-up, and what it means that we now believe there was a cover-up, and how we now act as a result. It sees the Kennedy assassination as the great dividing point of the American century, the break from which we never recovered. John F. Kennedy began his administration with the pro-government rhetoric of his inaugural—“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country”—and yet the mystery surrounding his assassination, along with the lies of Vietnam and Watergate, set the stage for the anti-government rhetoric of Ronald Reagan and all of his acolytes, from which we still haven’t recovered.

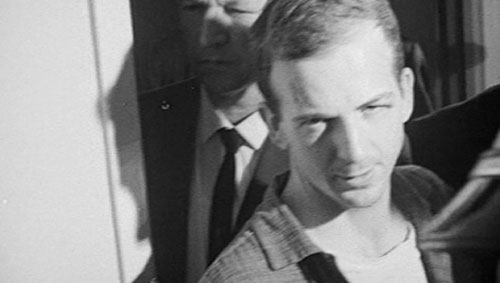

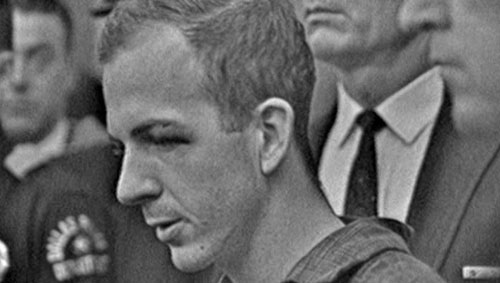

Is there a story of the last 50 years that’s been told more often than the Kennedy assassination? Yet filmmaker Robert Stone, working for PBS and “The American Experience,” finds footage, and photos, I’ve never seen before. Here’s Oswald in the Dallas police station professing his innocence so matter-of-factly that I began to believe him:

Oswald (in glare of TV lights): I'd like some legal representation, but these police officers have not allowed me to have any. I don't know what this is all about.

Reporter: Did you kill the president?

Oswald: No, sir, I didn't. People keep asking me that. ... They are taking me in because of the fact that I lived in the Soviet Union. I’m just a patsy.

One suddenly wonders: Hey, how did they trace him to the murder of Officer Tippit? How did they find him in that Dallas movie theater? How did they make him the focal point of the worst American murder of the 20th century?

Newsman: Was this the man that you believed killed President Kennedy?

Dallas police: I think we have the right man.

You think?

Dan Rather: Confusion reigned inside the Dallas police station.

Confusion?

Abraham Zapruder didn’t help. Instead of showing his film to the American people, he hired a lawyer and sold the rights to Life magazine, which printed individual frames. The film itself wouldn’t be shown on television until 1975.

Oswald’s mother didn’t help. She said her son was being framed, which one expects, but she also said her son was a government agent, which raised spectres.

Jack Ruby certainly didn’t help.

Did Mark Lane? The New York lawyer became the first man to openly question whether Oswald acted alone, in a December 1963 article in The National Guardian entitled “Lane’s defense brief for Oswald.”

Did the Warren Commission? Shouldn’t its hearings have been public? Shouldn’t we have taken our time with the matter instead of rushing out a verdict before the 1964 elections?

Yet, at the time, most Americans accepted the lone-gunman theory. That would quickly change as conspiracy books began appearing, then proliferating, two and three years later: First Lane’s “Rush to Judgment,” then Edward Jay Epstein’s “Inquest: The Warren Commission and the Establishment of Truth.” Then it was off to the races.

Initially outsiders were blamed. It was Castro or the KGB. It was the South Vietnamese government, responding to the Diem assassination. Eventually we began blaming ourselves. It was some rogue CIA element. It was some right-wing element that wanted to stay in Vietnam just as JFK was getting ready to pull us out. “And like all those theories,” Mailer says, “it had a certainly plausibility and a depressing lack of proof.”

That didn’t stop New Orleans D.A. Jim Garrison, wild-eyed and bug-eyed, and the worst of the conspiritorialists, who went after Clay Shaw, a prominent, closeted businessman. Stone (Robert, not Oliver) includes a fascinating 1967 news report critical of Garrison:

Garrison’s investigation has seemed to concentrate on homosexuals. That of course is an old police trick, and homosexuals have been a particular target of Garrison’s over the years. Even members of his staff have been privately critical of his emphasis on men whose deviation makes them vulnerable.

1968 didn’t help. Both MLK and RFK were assassinated by “lone gunmen.” Both were progressives. How could it not be conspiracy? (But did it have to lead to the inanities of “The Parallax View”?)

Post-Watergate, the Church Committee detailed all of those early 1960s CIA assassinations of foreign leaders. Was Malcolm X more right than he knew? Was the JFK assassination a case of the chickens coming home to roost?

It’s the Ruby factor that’s always bugged me. He had mob ties. He was a strip-club owner. Yet he killed Oswald, effectively silencing him, out of respect for Jackie? Out of sudden anger? Tie that with the difficulty of Oswald’s shot, of squeezing three bullets out of the 6.5 mm Carcano rifle in the time allotted, and of the whole back-and-to-the-left thing, with that final shot, the kill shot, looking, in the Zapruder film, like it’s blasting him from the front, well, you know, maybe there was something to it.

It’s Jack Ruby’s dog who pushes us back from the brink. Oswald was scheduled to be moved at 10:00 a.m. that Sunday morning. Here’s Hugh Aynesworth, a Dallas reporter:

Ruby slept 'til probably 9:30 or 9:20 something of that sort, and then he drives with his dog down to the Western Union and sent a telegram at 11:17 that morning. Came out and he looked one block up and he saw the crowd there at the police department. Jack Ruby was always on the scene of action, whether it be a fire, whether it be a raid, whether it be a parade, whatever. He had to be there. And he knew some of those cops. The fact that he left the dog in the car indicates to me that he thought he was going down to send a telegram and go back home. He took that little dog everywhere with him.

Few have assumed conspiracy longer and more vocally than Norman Mailer—yet even he comes around. “The internal evidence just wasn't there,” he says. “There were too many odd moments that just didn't add up.” Instead he focuses on Oswald’s mindset:

I think what Oswald saw was that if he committed the crime, if he assassinated Kennedy and he got away with it, then he would have an inner power that no one could ever come near. If he was caught, well then, he was quite articulate, he would have one of the greatest trials in America's history, if not the greatest, and he would explain all of his political ideas. He would become world famous and might have an immense effect upon history ...

When he shot Tippit, I think at that point he knew he was doomed because he could no longer make the great speech. If you shoot a policeman forget it, you're a punk. And so after he was caught he did nothing but protest his innocence and say, “I’m a patsy.”

“If you shoot a policeman, forget it, you're a punk.”

“This is not a whodunnit,” says Stone (Robert, not Oliver) in a DVD special features interview. “This is what a whodunnit has done to us.” He adds: “Conspiracy theory is part of the human condition; and it always will be.” Think of the doc as one Stone to correct another.

Is conspiracy the new American religion? The notion that we exist as small nothings for a short span of time in a cosmic eternity is unbearable, and thus we construct meaning out of it. The notion that this small nothing brought down the most powerful, glamorous man in the world is unbearable, and thus we construct meaning out of it. It was our enemies—foreign or domestic. It was the left or right. It was anything—please, God, let it be anything—other than little Lee Harvey Oswald.

—February 24, 2011

© 2011 Erik Lundegaard