Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

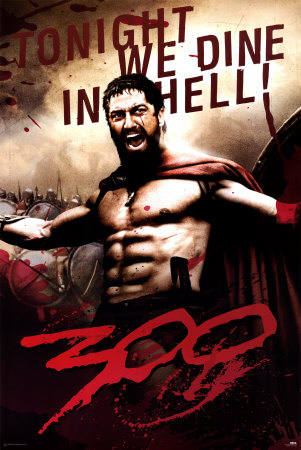

300 (2007)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Comic-book writer/illustrator Frank Miller creates worlds so cruel, so full of the awful dog-eat-dog laws of nature, that his protagonists are allowed to be both cruel and seething with moral righteousness. Which we, sitting in the dark, get to experience, too.

I’m sorry, but what kind of asshole likes a movie like “300”? What kind of asshole creates a movie like “300”? How weak do you have to feel inside to want to imagine a world like this? Or be in it.

There’s an early scene in which a 7-year-old boy slams another 7-year-old boy to the ground. He pins his shoulders down with his knees while he wails at the other kid’s face with punches. The boy on the ground is helpless but the boy on top keeps punching until with one final punch, delivered in thrilling, cinematic slow-mo, the blood—as Monty Python said of Sam Peckinpah’s scenes—goes pssssss.

| Written by | Zack Snyder Kurt Johnstad Michael Gordon |

| Directed by | Zack Snyder |

| Starring | Gerard Butler Lena Headey Dominic West David Wenham |

The boy on top is our hero. He will grow up to be King Leonidas of Sparta (Gerard Butler). And what he’s doing here, pounding the other boy into submission, is, by the story’s logic, necessary. He’s learning to be a man.

“Fascistic” is an overused word but I’d use it here. There is, at the least, a whiff of eugenics in the film. Defective babies in Sparta are discarded, dashed against the rocks, but one, a grotesque hunchback, Ephialtes (Andrew Tiernan), survives, and grows, and tries to join Leonidas’ men, the 300, in their stand against the Persian army in 480 B.C. Unfortunately, Ephialtes can’t physically do what needs to be done to be a soldier. He would be a weak link among the 300. So he becomes a weak link outside the 300. He is tempted by Xerxes (Rodrigo Santoro), the giant, androgynous King of Persia, with moaning women and soldier’s armor; and Ephialtes betrays Leonidas and the 300, leading to their downfall. In this manner, the cruelty of the world shows us we should be cruel first. The betrayal of Ephialtes, the hunchback who should’ve been killed at birth, reveals the wisdom of Sparta’s eugenics policy.

“Hitler” is an overused comparison, but .... OK, not Hitler. Nothing compares.

Except what was Hitler but a failed artist who created an ideal the opposite of himself? A small, dark, weak man, he extolled the tall, blonde and strong: the übermensch. And what is Frank Miller but a successful artist who has created an ideal the opposite of himself? A thin, frail, ugly man, he extolls the thick, powerful, and beautiful: the superman. Yes, I know: Most comic book creators are similar (the weak creating the strong), but with this difference: They tend to create worlds and situations in which mercy is a necessary quality. With great power comes great responsibility, etc. Frank Miller creates worlds and situations in which cruelty is a necessary quality. With great power comes the greater responsibility to crush the life out of people.

Some Spillane-ing to do

When we first see Leonidas as man and king, he’s roughhousing with his son and teaching him generic lessons about respect and honor, while his wife, Queen Gorgo (Lena Headey of “Game of Thrones”), watches with a benevolent smile. Then a messenger arrives from Persia, the strongest city-state in the world, asking for a token gesture that Sparta will submit to the will of Xerxes. Gathering all the wisdom and diplomacy he’s learned through all of his years of soldier training, Leonidas shouts “This! Is! Sparta!” before kicking the messenger (a Negro) and his men (wearing kufiyas) into a giant pit. Thus war is declared.

Except, whoops, Leonidas doesn’t have the authority to declare war. Democracy and all. He needs to ask the Ephors, leprosy-ridden, lust-ridden priests who live high atop a wind-swept mountain, to recommend to the Spartan council, vacillating old men, that war be declared. But the Ephors have been bought by Persian coin, as has Theron (Dominic Wests of “The Wire”), who runs the Spartan council. So what’s a soldier to do? Leonidas listens to his wife, who says, “Ask yourself, ‘What should a free man do?’” Then they have slow-motion sex. Then he gathers his 300 men for an epic battle at the Hot Gates.

Who’s memorable among the 300 besides Leonidas? There’s the Captain (Vincent Regan), who brings along his full-grown son, Astinos (Tom Wisdom), who is given shit by Stelios (Michael Fassbender). That’s about it. Oh, and Dilios (David Wenham). He’s our narrator. He will be the one-eyed survivor who tells the tale, sings the song, of the 300. And what distinguishes the only distinguishable characters from one other? Not much.

Has there been worse dialogue in a movie? At one point, the Queen gives us this Bush-era bumper-sticker slogan:

Freedom isn’t free at all. It comes with the highest of costs. The cost of blood.

After Astinos is beheaded in battle, we get this exchange:

Captain: Heart? I have filled my heart with hate!

Leonidas (nodding sagely): Good.

Meanwhile, Dilios goes for the noirish sentence fragments that Frank Miller loves:

There’s no room for softness. Not in Sparta. No place for weakness. Only the hard and strong may call themselves Spartans. Only the hard. Only the strong.

Even Mickey Spillane rolls his eyes.

So the Persians need to enter Sparta through a small strip of land, the Hot Gates, where their numbers are meaningless. That’s where Leonidas makes his stand. And he does, and they do, and the dead pile up. We get a lot of slow-mo battles, a lot of slow-mo blood splurging, a lot of hoo-ahs. The Persians send slaves, then their warrior class, then rhinos, elephants, and misshapen creatures. Nothing works. Until Ephialtes shows Xerxes the hidden path, and the 300 are traduced and outflanked. But their name lives on. Or at least their CGI-created abs.

The many against the few

Living on is a big part of it. Even as they battle, they fight over the meaning of the battle. They fight over the spin:

Xerxes: The world will never know you.

Leonidas: The world will know that free men stood against a tyrant. That few stood against many. And before this battle was over, even a god-king can bleed.

Which he totally does.

So that’s the meaning of the 300: the few standing against the many. But what’s the meaning of “300”?

It’s the many (moronic moviegoers) standing against the few (anyone with a brain). Thing made a mint: $210 million in the U.S., $456 million worldwide. It remade the month of March as potential blockbuster territory. And it’s still popular! Its current IMDb rating is 7.8. Compare this with “West Side Story” at 7.7, “The Hurt Locker” at 7.6, “An American in Paris” at 7.3.

It helped make a B-picture star out of Butler, and launched Zack Snyder’s directorial career. Without it, would we have gotten two of the worst movies ever made—Miller’s “The Spirit” and Snyder’s “Sucker Punch”?

It’s huge in the gay community, too. Do the chest thumpers know that? It’s basically gay porn. It’s beautiful, nearly naked men in high-camp situations.

But its larger meaning is the stuff at the beginning of this review. It’s the fascistic tendencies, the love of blood and cruelty, the easy soldierly morality. “300” took the usual action-movie wish-fulfillment fantasies and turned them up to 11, as in 9/11, as buff British actors played the brave western heroes and haughty minority actors played the bribing, thieving, butchering Ay-rabs. Sure, the 300 lost. But their sacrifice spurred the reluctant majority to final victory. In this regard, it’s like “The Alamo,” but with John Wayne and Richard Widmark clad in undies and capes and shouting “Hoo-ah!” in the rain. It’s a great cultural artifact of a warped society: ours.

—March 12, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard