Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

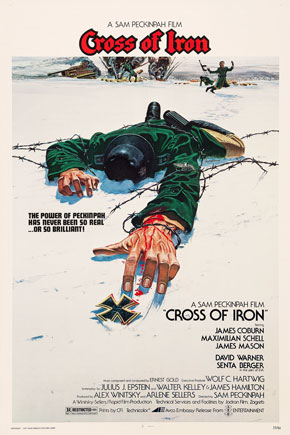

Cross of Iron (1977)

Cross of Iron contains the trappings of a generic war movie (tough platoon sergeant leading men against impossible odds) as well as the trappings of a World War II film made in the seventies (long hair, cynical attitudes, a disrespect for authority). But because the director is Sam Peckinpah, there's an individual, artistic sensibility at work within this structure. Peckinpah is constantly taking us places we don't expect, showing us images that burn in our minds, and denying us facile cinematic satisfactions. It helps that the film isn't an American production but was made jointly between the British, Germans and Yugoslavians. No Hollywood producer hung over Peckinpah's shoulder demanding he add the obvious.

Written by:

Julius Epstein

James Hamilton

Walter Kelly

(based on the novel by Willi Heinrich)

Directed by:

Sam Peckinpah

Starring:

James Coburn

Maximilian Schell

James Mason

David Warner

Klaus Lowitsch

Vadim Glowna

Roger Fritz

Dieter Schidor

Burkhard Driest

Fred Stillkrauth

Awards:

Golden Screen, Germany

Quote:

"What will we do when we lose the war?"

"Prepare for the next one."

The film begins with a reconnaissance platoon, led by Sergeant Steiner (James Coburn), creeping through the woods, preparing for attack. You root for them until you discover a) they're German, and b) it's near the end of the war, the eastern front is crumbling, and they're actually in retreat. Nevertheless they attack a Russian platoon and take a Russian boy prisoner. Upon returning to their unit, Steiner is confronted by a newcomer, Captain Stransky (Maximilian Schell), who reminds him of the "no prisoners" policy and demands he execute the boy. Steiner refuses. Our first indication that these ain't your typical cinematic Wermarcht.

Other indications come quickly. As the men talk, complain, fart, joke, one is reminded of M*A*S*H, Robert Altman's 1970 film about the Korean conflict. The troops are dirty, bitter, defeated, waiting to go home; they are merciful to the enemy; they celebrate a comrade's birthday. One soldier even sports a bushy Elliot Gould-type moustache. Their colonel, Brandt (James Mason), is benevolent. And while Captain Stransky quickly establishes himself as the villain — an aristocratic officer from an old Prussian family who had himself transferred to the eastern front in order to win the distinguished Iron Cross medal — he's not a Nazi. In fact, we don't meet any Nazis. Just Germans, please.

While repelling another Russian attack, Steiner suffers a concussion and wakes up in the clean, safe environs of a German hospital, where he disrespects authority, and wins the affections, after some slight physical struggle (this is Peckinpah, after all) of a German nurse. But Steiner's mind isn't right — and one senses it's not just the concussion. He sees things that aren't there and reacts with violence to placid situations. Even though the concussion is his ticket home, and even though he's got a German babe, he returns to his unit. "I have no home," he says, without self-pity.

Back at the front he discovers that Stransky applied for the Iron Cross because of supposed heroics during the recent attack, and used Steiner — whom he assumed gone for good — as a witness. Steiner contradicts him, and there's trouble. When the unit pulls out, Stransky purposefully leaves Steiner's platoon behind. Thus Steiner must lead his men through miles and miles of enemy territory in order to get to the temporary safety of temporary German land.

The battle scenes throughout are vivid and chaotic, and the shot of a truck running over a mud-bound corpse seems brutally accurate because of — rather than despite — its gratuitous nature. Coburn, underrated, gives a stellar performance as a conflicted man among men, while James Mason's portrayal of Colonel Brandt is subtle and layered. At one point, after mentioning various retreating strategies, he gets a gleam in his eye and expounds on plans of conquest: "To Leningrad and Moscow!" he tells Captain Keisel (David Warner). You think he's lost it. A second later he smiles, defeated, and you realize he was merely mocking earlier German pretensions.

The ending is where Peckinpah's sensibility truly emerges. Generally, in these types of films, when heroes have been long-suffering at the hands of villains, the audience expects, and thirsts for, retribution. Peckinpah has two opportunities to give us this, and denies us both times. In the first instance he demonstrates that retribution isn't satisfying at all but necessary and barbaric and disturbing. In the second instance, retribution arrives in a subtler fashion. Steiner and Stransky wind up fighting together, and Stransky reveals his ineptitude — to Steiner's uproarious laughter. But that's it. Abruptly, the film ends, before we find out what happens to Steiner and Stransky and Brandt. It ends before the end, perhaps because there is no end — a thought reinforced by a quote from Bertolt Brecht that flashes on the screen during the credits:

Don't rejoice in his defeat, you men.

For though the world stood up and stopped the bastard,

The bitch that bore him is in heat again.

It's a quote that never goes out of fashion.

—January 25, 2002

© 2002 Erik Lundegaard