Wednesday December 16, 2009

Review: “Where the Wild Things Are” (2009)

WARNING: WILD-RUMPUS SPOILERS

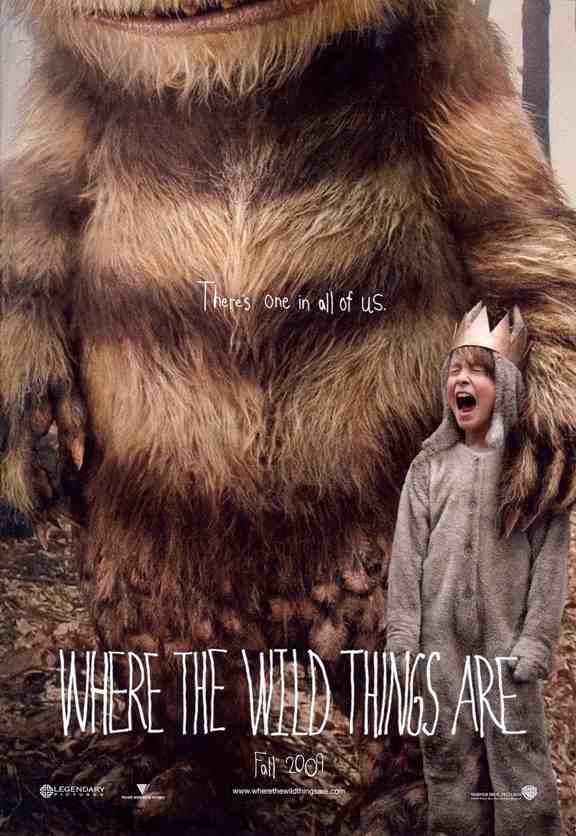

Both Maurice Sendak’s “Where the Wild Things Are” and I were born in 1963, and by the time I was Max’s age it was hugely popular but I wasn’t a fan. I guess I didn’t have much of a wild thing in me. I was a sickly kid, and fairly obedient, so not the type to tackle the family dog or start a snowball fight with bigger kids—both of which Max (Max Records) does in the first 10 minutes of Spike Jonze’s adaptation and expansion of Sendak’s work. It’s a brilliant first 10 minutes. Before we see anything we hear Max, humming, and before we see Max we see his handiwork: all of the movie-studio logos,  from Warner Bros. to Legendary Pictures, have been defaced, the last one reading M-A-X. Then we get Max himself, in wolf costume, chasing and tackling the family dog, at which point Jonze freeze-frames and gives us the title in childish script. At which point I went: “This is going to be good.”

from Warner Bros. to Legendary Pictures, have been defaced, the last one reading M-A-X. Then we get Max himself, in wolf costume, chasing and tackling the family dog, at which point Jonze freeze-frames and gives us the title in childish script. At which point I went: “This is going to be good.”

The photography is so muted, the colors so washed out, that the movie not only feels like it takes place in the 1970s but was filmed in the 1970s. Max is a rambunctious kid, possibly friendless, living with a teenaged sister and a divorced mom (Catherine Keener). When friends come to pick up his sister, he attacks them with snowballs and then gleefully runs back to his newly made snow fort. But they’re wild things, too, and bigger, and they follow and collapse the fort, leaving Max tearful—probably less physically hurt than emotionally hurt. His sister watched the destruction and did nothing. In revenge, he runs into her room, stomps the snow off his body, rips up gifts he’s made for her. Anger spent, regret sets in. This cycle of creation-destruction-regret continues throughout the movie.

We see him briefly at school. His science teacher is offhandedly explaining that the sun is a fuel source, and, like all fuel sources, will eventually expend itself and everything in our solar system will die. Attempting to cover up this awful fact, he digs deeper: He talks up the ways mankind will destroy itself before then. More creation-destruction-regret cycles. More callbacks to the 1970s. Back then, in the midst of my own parents’ divorce, it seemed I was surrounded by destruction scenarios, and one in particular stuck with me: an “In the News” report (sponsored by Kellogg’s) shown between Saturday-morning cartoons, in which it was reported that a graduate student wrote his doctoral dissertation on how to build an atom bomb. The meta-message: If one individual can do it, what country, with many individuals at its disposal, can’t? The knowledge was out there and couldn’t be bottled up. It made you feel small and powerless. It made you cling to fantasies of being all-powerful.

Max clings to such fantasies. His sister’s on the phone and his mother’s entertaining a man who’s not his father. Everything’s moving away from him, he has no say, and he’s bored. So he rebels. He acts bratty with his mom, then fights with her, then bites her—the act, not only of a wild thing, but of the powerless. Then he runs away. He finds a boat in a creek, gets in, and sails away to the island where the Wild Things are.

In his journey, Jonze emphasizes the smallness of Max against the vastness of the ocean, the deserted beach, the steep cliff face, and, finally, the Wild Things themselves, who crowd around and talk of eating him until his cry of “BE STILL!” stuns them into silence. Then he declares himself their king. In essence, this restores things to the way Max perceived them early in life. He’s small and powerless, surrounded by big, powerful beings, with big heads and big mouths, but he rules.

On the island, events unfold that, one imagines, mirror events in Max’s real world. Carol (James Gandolfini). a defacto leader of the Wild Things, and both father and buddy to Max, is estranged from KW (Lauren Ambrose), who’s off with Bob and Terry. “What about loneliness?” Carol asks Max during his coronation. “Will you keep out the sadness?” So even in Max’s fantasy there’s an immediate sense that things are not whole. But in the midst of their “wild rumpus,” as they run, jump, howl at the moon, KW returns, and they all hogpile together and sleep together, rather than in the separate cocoons (literal and metaphoric) that Carol was smashing earlier. “We forgot how to have fun,” Carol says as they drift off to sleep. Max showed them.

On the island, events unfold that, one imagines, mirror events in Max’s real world. Carol (James Gandolfini). a defacto leader of the Wild Things, and both father and buddy to Max, is estranged from KW (Lauren Ambrose), who’s off with Bob and Terry. “What about loneliness?” Carol asks Max during his coronation. “Will you keep out the sadness?” So even in Max’s fantasy there’s an immediate sense that things are not whole. But in the midst of their “wild rumpus,” as they run, jump, howl at the moon, KW returns, and they all hogpile together and sleep together, rather than in the separate cocoons (literal and metaphoric) that Carol was smashing earlier. “We forgot how to have fun,” Carol says as they drift off to sleep. Max showed them.

The next day, in a journey across the desert, Carol shows Max his secret cave with his model city, and Max declares that they will build their own city, a real city, where only things that they want to happen will happen. This city, this home, winds up looking like the cocoons they were smashing earlier, but big enough for everyone. Shortly after, though, Max follows KW across the desert to meet Bob and Terry, two owls whose wisdom is incomprehensible, and she brings them back to the new perfect home, setting in motion its destruction. “Why did you bring them here?” Carol asks Max angrily. “This was supposed to be for us.” For a time, Max distracts everyone with a dirtball fight but it mirrors the earlier snowball fight, ending badly with hurt feelings. Everything is breaking up again. The Wild Things demand that Max use his powers to make everything right but his powers turn out to be a robot dance with which, earlier in the movie, he’d tried to cheer up his mother. “That’s what we waited for?” they ask in disbelief. Carol’s anger can barely be contained. “It wasn’t supposed to be like this,” he says. “You were supposed to keep us safe.” Others counsel acceptance: “He’s just a boy pretending to be a wolf pretending to be a king.”

In this way Max’s fantasy of absolute power and absolute safety turns into a fable of acceptance. Every Wild Thing has faults. Carol is fun but with a hair-trigger temper, KW is maternal but keeps bringing in agents of destruction, Judith (Catherine O’Hara) is carping and critical but often correct. Ira (Forest Whitaker) can make great holes but he’s passive. Alexander (Paul Dano) is a goat no one listens to. And Max is a boy, made king, made parent, and made to recognize the limits of parental power and authority. Things break up. Things change.

Is “Where the Wild Things Are” a movie for kids? I don’t know. My nephew, Ryan, 6, liked it, while my nephew, Jordan, 8, didn’t. But it’s definitely a movie for adults. It has the feel of a classic. Then there’s this high praise from a friend, a mother with two sons: “It helped me understand boys.”

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)