Movie Reviews - 2000s posts

Thursday March 29, 2012

Movie Review: The Incredible Hulk (2008)

WARNING: PUNY SPOILERS

How do you live down a box-office bomb of gamma proportions? How do you reboot a movie without starting from scratch? “The Incredible Hulk”—the one with Ed Norton—does both. It starts out very, very smart, like Bruce Banner, and winds up kinda dumb, like the Hulk, but it’s still better than its predecessor. Its trajectory is its hero’s trajectory. That happen often?

The box-office bomb of gamma proportions was Ang Lee’s “Hulk” from 2003, and, no, don’t tell me these two movies basically grossed the same amount. They did, of course: domestically ($134m to $132m) and worldwide ($263m to $245m); and if you adjust for inflation, Ang Lee’s movie actually grossed more in the states: $171m to $147m. But the 2003 version came to us fresh. There was excitement about it. It had nothing to live down. The 2008 version came to us with a stink attached, Ang Lee’s stink, and a general used quality about it. Really? That story again? Didn’t we just do this thing?

More and more, that’s how we feel about the movies these days: Really? Didn’t we just do this thing?

More and more, that’s how we feel about the movies these days: Really? Didn’t we just do this thing?

Hanging out in Rochina Favela

First, “The Incredible Hulk” is definitely a reboot. None of the actors are the same. Ed Norton replaces Eric Bana as Bruce Banner, Liv Tyler replaces Jennifer Connelly as love interest Betty Ross, and William Hurt replaces Sam Elliott as nemesis Gen. “Thunderbolt” Ross. No one replaces Nick Nolte as David Banner, Bruce’s batshit dad, because they jettison that storyline. No argument from me.

The origin of the Hulk is rebooted. Rather than, as in Ang Lee’s version, David Banner passing on his genetic modification to his son, who accidentally gets an insane dose of gamma radiation while running the same kinds of science experiments his father ran—even though he knows nothing of his father—this Bruce attempts to modify Prof. Reinstein’s WWII-era super soldier formula, which made Steve Rogers Captain America, for the military and under the watchful eye of Thunderbolt Ross. Then he experiments on himself. Oops.

The most fascinating aspect of the rebooted origin? They encapsulate it in the credit sequence. Consider it shorthand: experiment in lab, wink to Betty, oops, Hulking out, Betty bruised in the hospital, Gen. Ross injured and angry, Bruce on the lam and ... done.

This allows the movie proper to start in the same place the last one left off: with Bruce on the lam in Latin America. That’s smart.

Smarter? Our protagonist. He’s a scientist, and, for the first half of the movie, he never stops being a scientist. He’s stopped running in Rochina Favela, the largest shantytown of Rio de Janeiro, where he’s gotten a job at a bottling plant and is tackling his rather unique problem by pursuing both temporary solutions and permanent cures. The latter involves rare flowers and blood samples and microscope slides and never pan out (or we’d have to change the title of the movie). The former involves heart-rate monitors and yoga and martial arts lessons. “The best way to control your anger is to control your body,” his teacher tells him. Then he slaps him. We’ve just seen Bruce watching a TV re-run of “The Courtship of Eddie’s Father” in which Bill Bixby, who played David Bruce Banner in the 1970s “Hulk” TV series, gets slapped, so that’s a nice echo. His teacher then tells him to drive his anger from his chest into his stomach. Days without incident? 158.

Unfortunately (OK, fortunately), the bottling plant has the usual volatile elements: an impossibly pretty girl, Marina (Débora Nascimento), who likes him, and a bully (Pedro Salvín), unnamed, who doesn’t. At one point, interceding for Marina, he tells the bully, in his fractured Portuguese, and in a hilarious homage to most famous line of the TV series, “Don’t make me ... hungry. You wouldn’t like me when I’m ... hungry.”

Gen. Ross is still looking for him, of course. “As far as I’m concerned,” he says with his usual Capt. Ahab tunnel-vision, “I consider that whole man’s body the property of the U.S. Army.” And when some of Bruce’s blood spills on a bottle that makes its way to Milwaukee, Wisc., where an elderly man—our Stan Lee cameo—drinks it and collapses, Gen. Ross is alerted to the whereabouts of Banner, and, per James Monroe’s doctrine, or at least Teddy Roosevelt’s corollary, he sends in the troops. Which leads to a great chase through the shantytown—a chase in which the pursued can’t let his heart-rate get above 200.

Gen. Ross is still looking for him, of course. “As far as I’m concerned,” he says with his usual Capt. Ahab tunnel-vision, “I consider that whole man’s body the property of the U.S. Army.” And when some of Bruce’s blood spills on a bottle that makes its way to Milwaukee, Wisc., where an elderly man—our Stan Lee cameo—drinks it and collapses, Gen. Ross is alerted to the whereabouts of Banner, and, per James Monroe’s doctrine, or at least Teddy Roosevelt’s corollary, he sends in the troops. Which leads to a great chase through the shantytown—a chase in which the pursued can’t let his heart-rate get above 200.

Director Louis Leterrier uses Rochina Favela well. In the beginning, we get a great panning shot over the shanties, which seem to stretch on forever. The chase sequence through the shanties is fun. But we’re 23 minutes into this thing. Time to Hulk out already.

Extra credit at Culver University

What’s the worst part of being Bruce Banner? Is it the Hulking out? Or is it that everyone watching—you and I—want you to Hulk out? Everything Bruce is trying to prevent is what we’re there to watch. He’s second billing to his alter ego. If he ever succeeded in curing himself we’d be pissed.

Unfortunately, the Hulk isn’t that interesting, either. He’s just rage in a 10-foot-tall, CGI-created, green monster. He smashes and leaves. We want him to smash, certainly. We want him to take out the bully. He’s the ultimate wish fulfillment for the weak, a Mr. Hyde for the superhero generation. But then what? Run, leap, wake up as Bruce Banner under a waterfall in Guatemala. Oh, the places Hulk takes you.

Holding up his pants, Bruce heads back to the states and Culver University, Virginia, where it all began. He’s been in contact with another scientist, a Mr. Blue (to his Mr. Green), who, to help him, needs more data, and that data is at Culver. So is Betty Ross.

Culver is also where we get our other, requisite Hulk cameos. Bruce’s old friend, Stanley (or ‘Stan Lee’), a pizza shop owner, is played by Paul Soles, who provided Bruce Banner’s voice in the 1966 cartoon; and, to retrieve his data, Bruce bribes a campus security guard, with a pizza. The guard is played by the original Hulk, Lou Ferrigno.

But the data’s gone, expunged by Ross, and Bruce is about to go on the lam again when Betty sees him, intervenes, and they have a few scenes in the rain. The movie slows here, as mushy girl stuff usually does. It picks up again when the couple, betrayed, are set upon by the U.S. Army, including Emil Blonsky (Tim Roth), a Russian-born, British-educated soldier with a love of battle, who wants to take on the Hulk, who wants to be the Hulk, and who will become, with the help of Gen. Ross and Mr. Blue, the Abomination. But first, a good chase on campus. Bruce is trapped in a glass overpass, into which they shoot gas canisters, but ... too late.

While this CGI Hulk has more weight and personality than Ang Lee’s CGI Hulk, it’s still pretty boring. Hulk smashes, looks around, is attacked and smashes again. Ross almost incinerates Betty, his daughter, whom Hulk protects, and, after an angry glance, the two fly off to a safe location: a cave under a cliff during a lightning storm. I like Hulk roaring at the thunder. That’s good, impotent rage. I like Gen. Ross being told off by Betty’s now-ex, Leonard (Ty Burrell), and then muttering to himself, “Where does she meet these guys?” It’s a glimpse of the father we don’t see enough.

A rage in Harlem

The third act in New York should be better than it is. Bruce and Betty go there to meet Mr. Blue, Tim Blake Nelson, who gives an inspired, loopy performance as Samuel Sterns, the scientist who will become the villainous Leader. Eventually. In the sequel to this reboot. If there is one.

But Bruce, here, is more acted-upon than acting. The one time he does act, purposely falling from a U.S. Army helicopter to take on the Abomination in the streets of Harlem, it’s pretty dumb. He’s already told Betty he doesn’t remember much about being the Hulk; just fragments, images. So how does he know Hulk won’t cause more damage? How does he know Hulk won’t team up with Abomination to smash? But Hulk is hero. So Bruce drops. And we get our giant CGI battle, which, to me, is as interesting as watching two dudes play a video game. Which is to say: not at all.

I’ll say this for Ang Lee’s version: It gave us that moment when Bruce admits: “You know what scares me the most? When it comes over me, and I totally lose control... I like it.” We should have something like that here. Instead: CGI battle, Hulk wins, leaves. Is the Abomination still alive? What happens when he wakes? Has Gen. Ross learned his lesson? Shouldn’t we get a mea culpa from the son of a bitch?

Nothing.

The end implies that Bruce, via meditation, is learning to control the Hulking out, which sets up “The Avengers” movie but which goes against all Hulkian principles. His eyes open, green and knowing, and the movie ends. Not a bad end, I suppose. Unfortunately, it’s the last we’ll see of Ed Norton as Bruce Banner. They’ve replaced him with Mark Ruffalo, a good actor, who I’m sure will be fine. But some old, Marvel-style continuity would be nice now and again. Some sense that actors matter. Some sense that we’re not all the stuff of CGI.

Wednesday March 14, 2012

Movie Review: Fantastic 4: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007)

WARNING: IF THIS BE SPOILERS...

SCENE: Upper floors of the Baxter Building, New York City.

TIME: Hours after the Silver Surfer has destroyed Galactus, destroyer of worlds, and saved the Earth.

ENTER: Reed Richards (Ioan Gruffodd), Sue Storm (Jessica Alba), Johnny Storm (Chris Evans) and Ben Grimm (Michael Chiklis). They’re weary and battered and three of the four slump into whatever furniture is available, while Reed Richards stands.

REED: Alright, I know we’re all tired. But now that Galactus and the Silver Surfer are gone, and the Earth is safe again, what are some of the lessons we learned from this latest adventure? Anyone?

[Pause. Everyone looks around.]

SUE: Well, I learned that with great power comes great responsibility!

BEN: Uh... Isn’t that Spider-Man’s thing?

SUE: OK, so not in those words. But ... you know. Like before I was worried that Reed’s and my fantabulous wedding would be too much of a media storm and would affect our lives, and our eventual kids, and we wouldn’t have normal lives? And I wanted Reed to settle down and be a professor and me a housewife somewhere far, far away? After we saved the world, I realized we couldn’t run away from all that!

JOHNNY: Actually, sis: First, you worried you wouldn’t get married. Remember? Only when you were about to get married did you worry about getting married.

SUE: Oh, right.

JOHNNY: That was kind of a drag, to be honest.

BEN: Plus we didn’t save the world, Susie. Surfer dude did.

SUE: I did my part! If it wasn’t for my big blue eyes and full lips, and the love Reed demonstrated for me, Norrin Radd wouldn’t have been reminded of his love for his own woman ... Shallow Bal?

REED: Shalla-Bal. But I don’t think he mentioned her name in this—

SUE: The point is ... Because of me, he was reminded of her, and so he decided to save us. Without me and her, that saving-us part wouldn’t have happened.

JOHNNY: Can I just say: Surfer? Surfboard? Hello! It’s not 1965, people.

BEN: People still surf.

JOHNNY: But it’s so dumb. Just because Jack Kirby read an article about surfer dudes back in 1965 and created this guy doesn’t mean we gotta keep going with it. I mean: surfing outer space? What the hell?

BEN: Me? I just didn’t like how he totally stole our thunder. We didn’t even need our super-powers to save the world. Just Susie’s big eyes.

JOHNNY: Which look totally fake, by the way.

SUE: They do not!

BEN: King Kirby and Stan the Man, back in issues 48 through 50, they let us stop Galactus. Here we’re like walk-ons in our own freakin’ movie.

REED: Plus, if the Silver Surfer could actually defeat Galactus, why didn’t he do it before? How many worlds has he helped destroy along the way?

BEN: I never understood what people see in that guy.

JOHNNY: I never understood why we kept switching powers.

BEN: That was weird, wasn’t it? And of course in the end—poof! Gone.

REED: I think the rationale behind the power-switching was three-fold: One, it allowed for comic relief and hijinks in the middle of the adventure...

BEN: Comic relief when the world is ending?

REED: ...Two, it gave Chiklis face time, which he needs.

BEN: True that.

REED: ...And three, it gave all the fanboys in the crowd a chance to see Sue naked.

SUE: Reed!

REED: Sorry.

JOHNNY: He’s right, sis.

BEN (laughing): Remember what you said, Susie?

JOHNNY (in high-pitched voice): “Why does this always happen to me?”

BEN (laughing): Why does this always happen to me? That’s a good one!

SUE: Guys!

REED: Sorry, Sue. Fanboys want wish fulfillment, and that’s where Johnny and Ben come in—and me, to a certain extent—but...

BEN: But they also want to get their rocks off.

JOHNNY: And that’s where you come in.

SUE: [Sighs.]

JOHNNY: Yeah, like that. But deeper. More chesty.

REED: OK. Any other lessons learned?

JOHNNY: Well, I learned that, sure, being a shallow, hotshot celebrity with hot chicks and a cool superpower is all well and good. But at the end of the day, or the end of the world, whichever comes first, you really want that special someone to cuddle with.

REED: With whom to cuddle.

JOHNNY: Whatever. So anyway that’s why I’m going for the hot military chick.

REED: What’s her name again?

JOHNNY: You know... hot military chick. Captain Something.

BEN: True love.

REED: What do like about her?

JOHNNY: I don’t know.

REED: What do you have in common?

JOHNNY: I don’t know. She’s... She was there at a time when I realized that boffing girls isn’t, you know, fulfilling.

BEN: Poor you.

REED: Didn’t you also learn something about being part of a team, too?

JOHNNY: Yeah. That was weird. Kind of tacked on. And wasn’t that Sue’s lesson?

BEN: What about you, Big Brain? You learn anything?

REED: Well, I learned that some of the officers in the U.S. Armed Forces aren’t very nice.

JOHNNY: Totally! That dude was a major asshole.

BEN: General Asshole.

JOHNNY: He asks for our help and then insults us the whole time?

BEN: He got you so mad you had to brag about yourself. (Laughs.)

JOHNNY: Oh man, that was dumb. I was so embarrassed for you.

SUE: Right, right. The whole “I’m the quarterback and you’re the nerd.” “Well, I’m the nerd with the hot chick and you want my help.”

REED: I know, I know.

JOHNNY: Wait, what was that other line? The lamest line of them all?

SUE: “It’s 15 years later and now I’m one of the greatest minds of the 21st century!”

JOHNNY: That’s the one!

[Everyone but Reed laughs.]

REED: I know, I know. But I couldn’t stop myself. It was as if someone really, really stupid was inside my head making me say those words.

SUE: I know the feeling.

JOHNNY: Me, too.

REED: It’s odd. The whole thing. [He looks around.] It’s as if someone really stupid made us these narrow caricatures, then had us realize we shouldn’t be narrow caricatures. You know. Johnny’s shallow and flip so he has to get serious. I’m too serious, so I have to dance with models and brag about my brain. Sue wants to end the Fantastic Four because of what snarky girls say about her on TV, so...

JOHNNY: God, that was dumb.

REED: I mean, those are our lessons? While we save the world?

BEN: While we watch Surfer dude save the world.

JOHNNY: You’re right, Reed. And the sad thing is, at the beginning, it felt like it was supposed to be our greatest, most epic adventure. Yet it turned into our lamest adventure.

BEN: Probably our last one, too.

SUE: No, Ben. I learned my lesson. That we’re all in this together. Remember?

REED: I think he means something else, Sue.

JOHNNY: We’re getting the boot.

BEN: The re-boot.

REED: Eventually. When the taste of this one has finally left people’s mouths.

JOHNNY: Which should be in about ... 10 years.

BEN: What a revoltin’... shame.

[Pause]

SUE [mockingly]: “I’m one of the greatest minds of the 21st century.”

REED: I know, I know.

[Fade]

Thursday March 08, 2012

Movie Review: Fantastic Four (2005)

WARNING: EARTH’S MIGHTIEST SPOILERS

As you age, you begin to question the legend.

Legend has it that in the early 1960s, beginning with the utterly original Fantastic Four, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby rescued the superhero genre from the cheesy, soporific clutches of DC Comics and made it anew. They gave it continuity: what happened last issue mattered this issue. The characters became human and relatable: they fought; they moped; eventually they separated and divorced. Superheroes had always been wish fulfillment but it was Stan Lee’s particular genius to wed the fantasy (this guy is superstrong and can climb walls...) with identification (...even though he’s a mopey teenager like me!).

That’s the legend and it’s more or less true. What you begin to question is the utter originality of the Fantastic Four. As conceptions go, its wasn’t so immaculate.

Plastic Man, Invisible Man, Human Torch and ROMMBU!

I’m not talking about how DC’s Jack Liebowitz supposedly bragged about the sales of its Justice League of America comic books to Marvel publisher Martin Goodman, who then demanded, of his editor-in-chief Stan Lee, a team of superheroes. I’m talking about the superpowers. Each is derivative of an earlier character.  Mr. Fantastic can stretch like Plastic Man (created 1941), the Invisible Girl can turn invisible like the Invisible Man (created 1897), and the Thing is a rock creature like so many of the odd-named rock creations that kept Marvel afloat in their near superhero-less 1950s (Moomba and Krogarr and Rommbu and the like). The Human Torch, meanwhile, borrows both name and powers from the WWII-era creation of Carl Burgos. None of it is very original.

Mr. Fantastic can stretch like Plastic Man (created 1941), the Invisible Girl can turn invisible like the Invisible Man (created 1897), and the Thing is a rock creature like so many of the odd-named rock creations that kept Marvel afloat in their near superhero-less 1950s (Moomba and Krogarr and Rommbu and the like). The Human Torch, meanwhile, borrows both name and powers from the WWII-era creation of Carl Burgos. None of it is very original.

The Fantastic Four’s origin story, meanwhile, is inevitably trapped within the absurdities of its time. In Fantastic Four #1, published in November 1961, Ben Grimm is a test pilot (with a temper) and Reed Richards is a scientist (with a pipe), and they have to travel into outer space fast or else, in the words of Sue Storm, “the commies ... beat us to it!” Why does she tag along? Because she’s Reed’s fiancée, of course. Why does her younger brother, Johnny, tag along into outer space with the three of them? Because he’s the younger brother of the fiancée of the guy who, like, designed the whole rocket ship. Duh! And so all four sneak into the rocket ship at night and launch it, we’re told, “before the guard can stop them.” That’s guard, singular.

Despite the legend, in other words, some of it is pretty hokey stuff. So it’s not wholly the fault of director Tim Story (“Barbershop”; “Taxi”), and screenwriters Mark Frost (“Twin Peaks”) and Michael France (“Hulk”), that their 2005 movie, “Fantastic Four,” sucks.

R-E-S-P-E-C ... Aw, screw it

Story and company make attempts, feints, at updating and modernizing the story in a positive way. Reed Richards (Ioan Gruffudd) is now a brainiac scientist (without a pipe) who has gone broke, and who, with his pal Ben Grimm (Michael Chiklis), proposes to business tycoon and egomaniac Victor Von Doom (Julian McMahon), late of Latveria, that a cosmic storm may have been responsible for the evolutionary jump in humankind; and another cosmic storm, like the first one, is fast approaching and needs to be studied in space. Doom agrees, but demands a 75-25 split on any profits resulting from their scientific studies, then demands that his current girlfriend, and Richards’ old one, Sue Storm (Jessica Alba), along with her hotshot younger brother, Johnny (Chris Evans), who used to be Ben Grimm’s underling, come along for the ride. And that’s how they all wind up in space together—with Doom this time—to encounter those cosmic rays.

Except ... aren’t the filmmakers cadging the evolutionary bit from the “X-Men” movies? And does it even make sense considering the results? The next step in evolution is... becoming super stretchy? Or invisible? Or a rock man?

Except ... aren’t the filmmakers cadging the evolutionary bit from the “X-Men” movies? And does it even make sense considering the results? The next step in evolution is... becoming super stretchy? Or invisible? Or a rock man?

There’s an attempt to explain this, too—to wed the power to the personality—but it’s pretty weak connective tissue. Johnny’s a hotshot, so... Sue feels invisible to Reed, so... Dr. Doom tells Reed at the beginning that he’s “always stretching, always reaching for the stars,” so...

But the casting’s not bad, right? In theory? Gruffudd is properly dull and brainy and Chiklis is properly gruff and working class and Evans is cocky and flip and gives us some good line readings. And Jessica Alba... She takes off her clothes a lot. Right?

Alright, screw it, the thing’s just dumb, monumentally dumb. The filmmakers give us a feint at “X-Men”-like respectability but then double-down on dumb. The movie felt lost to me forever when Doom introduced Richards and Grimm to “My director of genetic research...,” and we get a shot of the 23-year-old Jessica Alba sauntering sexily toward the camera. No wonder his company goes under.

Doubling down on dumb

Here. Another example. Let’s say you’re a sexy nurse (Maria Menounos). Let’s say you’re such a sexy nurse that you’re only known as “Sexy Nurse” in the closing credits. And let’s say you have a patient, Johnny Storm, recently returned from outer space, and you’re involved in the fairly simple task of taking his temperature. He flirts a bit, then declares he’s going snowboarding even as you’re read his temperature: 208 degrees! WTF? So what do you do?

- Alert the doctor.

- Take his temperature again.

- Shrug and go snowboarding with him. Totally.

Then on the downhill run, right before your eyes, he bursts into flame, begins to fly a bit, then crashes into a snowbank where the heat from his body creates its own little snowbunny hot tub, which is where he stands, half naked, and invites you in. What do you do?

- Alert the doctor.

- Alert the fire department.

- Shrug, and begin to take off your clothes to join him.

The whole movie is like this. The big early set piece, the introduction of the FF to New York and the world, occurs on the Brooklyn Bridge. Ben Grimm is brooding there because his fiancée, Debbie (Laurie Holden), whom we’ve never met before, races outside in a short nightie to greet him, but runs, stumbles away when she sees the orange, rock man he’s become. Poor Ben! So he’s feeling sorry for himself when a jumper shows up and contemplates the East River. Ben turns to him and growls, “You think you got problems, pal?” (Good line.) The jumper stumbles back in panic, but into traffic, and Ben has to save him, which causes a massive, dozen-car pile-up in the middle of the bridge, which causes a firetruck to crash through the bridge’s barrier and teeter (like the schoolbus in “Superman: The Movie”) over the edge. It takes all of the powers of the Fantastic Four to save the firemen. The reaction to this is two-fold. The NYPD draw guns on the four, particularly on the giant orange rock man; but the NYFD, now saved, burst into applause, and they’re joined by the populace on the walkways, who aren’t freaked by the orange rock-man, or the super-stretchy guy, or the hot invisible girl. Why would they be? They know heroes when they see them. Even if the Thing did create the disaster in the first place.

Then it gets worse.

At this moment, with the four basking in the applause, Debbie suddenly shows up in the middle of the bridge. Was she drawn by the network coverage? Did she just happen to be there anyway? Is she going to ask for forgiveness? Of course not. She’s not supposed to be with him. He’s supposed to be with Alicia Masters (Kerry Washington), who’s blind, see, and so doesn’t mind that he’s an orange rock man. She goes beyond sight, and touch, and senses the good man within the hideous monster. Debbie, that bitch, doesn’t (hence the short nightie on the city streets). So on the bridge, as her fiancé is being applauded by all of New York, she removes her engagement ring and drops it on the pavement and walks away. Poor Ben! He then tries to pick it up but can’t with his giant rock fingers. Poor Ben! He’s trapped in a world he never made!

We have no emotional investment in Debbie and Ben at this point. We barely have emotional investment in Ben. And why is he always shocked when everyone stumbles away from him in panic? Has he forgotten what he looks like? Does he think people are better than they are?

Schtupping Sue Storm

I could go on. The high, reedy voice Doom has even when he dons his mask. The fact that they make Reed Richards quiet and dull rather than talkative and dull. The idiotic dialogue:

Johnny: Sue stop, you're not mum. Don't talk to me like I'm a little boy, okay?

Sue: Maybe I would if you stopped acting like one. Do you even hear yourself? Who do you think you are?

Johnny: Why is everyone on my ass? If you guys are jealous, that's fine; I didn't expect it to come from you, though.

Sue: You really think those people out there care about you? You're just a fad to them, Johnny!

But the dumbest part of the movie has to be the love triangle between Reed, Sue and Victor.

Reed and Sue were a couple in college but apparently he didn’t pay enough attention to her—he thought too much and didn’t act enough—so she left him. And now she’s Director of Genetic Research for Doom, Inc., or whatever it’s called, while dating its CEO, Dr. Doom. All of this is treated semi-comically. It’s used to get Reed Richards’ goat. Hah! Dude, you totally lost the sexy girl cause you think too much! You shoulda nailed that shit. Like daily. Like hourly. Totally.

Except...

- She’s dating the CEO? Is that how she got the job?

- She’s dating the CEO even though she doesn’t care for him? Does she always do this? Use her looks to advance her position with powerful men? Should this have been a Sam Peckinpah movie?

- She’s schtupping the CEO? She must be, right, because he proposes. So why didn’t we get that scene? Sue Storm and Victor Von Doom doing the nasty. The whole thing wouldn’t seem so semi-comic then. She wouldn’t seem so sympathetic then.

Seriously, comic-book geeks have to stop with this love-triangle shit between hero, villain and girl if they want the girl to remain sympathetic at all. The only reason Sue Storm remains sympathetic here is because in her moments alone with Doom she obviously doesn’t care for Doom. So why is she with him? Is she playing him? Does she know her own heart? If Reed Richards hadn’t come along with his cosmic-ray proposal, would she have married Doom, this rich man, and become vice president of the company?

Between Debbie, Sue Storm, and Sexy Nurse, women don’t come off well in “Fantastic Four,” do they?

Straw Man vs. Superman

Even if you don’t know the FF, even if you don’t know Ben Grimm from Rommbu, it’s obvious Sue and Reed will get together in this movie. It’s obvious Doom is creepy and vain and fixated on Reed Richards in an unhealthy way. So the love triangle, such as it is, is basically a straw-man subplot: created for the illusion of drama; created only to be torn down. We know where everything is going and it winds up there without anything interesting happening along the way. I suppose that’s where acting comes in. I suppose that’s where good dialogue and plotting and pacing comes in. “FF” gives us none of these.

Let’s look at something that works. Let’s look at, say, “Superman: The Movie.” We know that Superman will save Lois Lane so the question is how he saves Lois Lane. Wait, he doesn’t? She dies? She’s buried alive in her car? Oh, then he reverses the earth’s rotation to bring her back to life? That’s kind of lame.

So why does it work?

Pacing. Acting. Feeling.

Margot Kidder and director Richard Donner actually give us a sense of what it’s like to be buried alive, and choke, and die. It’s pretty horrific. Christopher Reeve gives us a sense of what it’s like to lose someone you love. His later sense of relief, as she bitches about her car, is palpable. It’s touching and funny at the same time.

What does it feel like to burst into flame? To stretch? To turn invisible? We get none of that in “Fantastic Four.” What’s it like to be in love? To lose your love? Sorry, can’t stop now. We’re in too much of a hurry to get to the next uninteresting moment on our fixed path to the inevitable end.

What a revoltin’ development.

Friday February 10, 2012

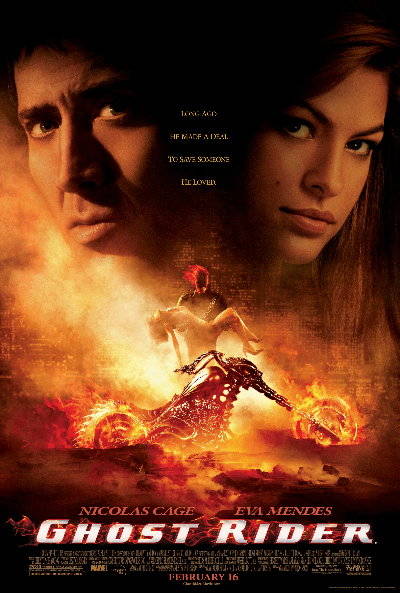

Movie Review: Ghost Rider (2007)

WARNING: SPOILERS

At what point did the makers of “Ghost Rider” decide, “Ah, fuck it”? When they hired Nicholas Cage instead of Eric Bana? When Cage began playing Elvis playing Johnny Blaze and no one said shit? When they hired writer-director Mark Steven Johnson, who was hot off his abysmal 2003 version of “Daredevil”?

Or was it when they read the source material?

“Ghost Rider” was part of that awful wave of horror-hero hybrids from Marvel Comics in the 1970s, a wave that began when the Comics Code Authority, which was rapidly losing its authority, allowed traditional horror characters back into comics. As a result, Marvel, which 10 years earlier had reinvented the superhero genre with Spider-Man, X-Men, and the Fantastic Four, was suddenly offering its version of creature-feature night: “Tomb of Dracula,” “Swamp Thing,” “Werewolf by Night,” “Son of Satan,” and, yes, “Ghost Rider,” in which a motorcycle stuntman named Johnny Blaze turns into a superpowerful, hell-spawned demon with a flaming skull, and rides around town doing … whatever it is he does. Does he fight crime or fight the Devil? Or both? I’m not sure because I never read the damned thing.

“Ghost Rider” was part of that awful wave of horror-hero hybrids from Marvel Comics in the 1970s, a wave that began when the Comics Code Authority, which was rapidly losing its authority, allowed traditional horror characters back into comics. As a result, Marvel, which 10 years earlier had reinvented the superhero genre with Spider-Man, X-Men, and the Fantastic Four, was suddenly offering its version of creature-feature night: “Tomb of Dracula,” “Swamp Thing,” “Werewolf by Night,” “Son of Satan,” and, yes, “Ghost Rider,” in which a motorcycle stuntman named Johnny Blaze turns into a superpowerful, hell-spawned demon with a flaming skull, and rides around town doing … whatever it is he does. Does he fight crime or fight the Devil? Or both? I’m not sure because I never read the damned thing.

A friend of mine did. What I thought was schlock—flaming skulls, chains and leather, chopper motorcycles—he thought was cool. This has been the basic disagreement between fans and non-fans ever since. What’s cool? What’s schlock? The makers of “Ghost Rider,” knowing they would never appeal to people like me, decided to double-down on schlock. They give us carneys and cowboys and yee-ha rubes and bounty hunters for the Devil and Eva Mendes doing newscasts in a tight, cleavage-baring shirt and Nicholas Cage doing Elvis doing Johnny Blaze. They give us ripostes that make Schwarzenegger’s seem scripted by Shakespeare:

Criminal: Have mercy!

Ghost Rider (low growl): Sorry! All out of mercy!

The movie is more plothole than story. Young Johnny Blaze (Matt Long) is about to ditch his father and their carney motorcycle act for true love, his sweetheart Roxanne (Raquel Alessi), for whom he carves initials into the only tree visible for miles. Except the cough Dad has? Cancer, dude. Totally. But in walks the Devil (Peter Fonda) with a proposition: Dad’s health for Johnny’s soul. While Johnny is thinking about it, oops, a drop of his blood spills on the contract. Apparently this makes it a done deal. Hardly seems fair to me, let alone legal. Isn’t there a lawyer Johnny could’ve hired? Blaze v. Mephistopheles. Who wouldn’t take that case? The arguments over jurisdiction alone would make a career.

The Devil being the Devil, which is to say devilish, cures Barton Blaze’s cancer but causes him to die in a motorcycle crash the same day. Doesn’t Johnny die, too, at the crossroads where the Devil lives? The contract has now been rushed into effect and the Devil issues a warning: “Forget about friends, forget about family, forget about love. You’re mine now, Johnny Blaze.”

At which point he disappears for 20 years.

During that time, Johnny (now Nick Cage) forgets about family, forgets about love, but gains fame as the Evel Knievel of his generation. He jumps everything—cars, trucks, helicopters—because he doesn’t fear death. Why should he? He doesn’t even know if he’s alive. But in his dressing room, with his friend, Mack (Donal Logue), he broods about second chances. Then he cranks the Carpenters. A nice bit, actually. My favorite bit in the movie.

At this point, Roxanne (now Eva Mendes) re-enters his world as a pushy TV reporter with a push-up bra and a bit of attitude for the way Johnny ditched her. But persistence wins her over again and they make a date. Unfortunately, and from the Dept. of Insane Coincidences, this is the very moment that the Devil’s son, Blackheart (poor Wes Bentley, who once seemed so promising), in defiance of his father, enters the world to take it over. The Devil can’t stop him (for some reason) but Johnny can (for some reason), which is why, instead of the date with the girl he ditched 20 years earlier because he’d become the Devil’s rider, he finally becomes, for the first time, the Devil’s rider. His body starts smoking, Cage starts overacting, and eventually his face bursts into a flaming skull. This initial transformation is long and traumatic but subsequent changes become smoother as the plot necessitates.

As for what brings Blackheart here? For that, backstory.

You see, there was another ghost rider before Johnny, a cowboy in the 19th century who was instructed to bring the Devil a contract claiming a thousand souls in the town of San Venganza. But he knew this contract would make the Devil too powerful so he reneged on the deal and galloped away and hid the contract. And that’s what Blackheart is after:the contract containing the lost souls of San Venganza.

Questions:

- How can anyone escape the Devil?

- How does anyone hide something from the Devil?

- Is Blackheart related to Daimon Hellstrom? How about Little Nicky?

In his quest, Blackheart gathers minions of his own, ghouls with long dark coats and long scraggly hair who can hide in the elements—there a sand guy, a water guy and a wind guy—and they leave a trail of dead bodies in their search for the contract. When Johnny shows up, Blackheart sics all three minions on him at once. Kidding. That would be too logical. They attack him one at a time so he can defeat them one at a time and lengthen out the movie.

But let’s fast-forward to one of the dumbest scenes in movie history. After his first transformation, Johnny wakes in a church graveyard, where a good-natured Texan named Caretaker (Sam Elliott), whose voiceover explained the San Venganza backstory to us at the beginning of the movie, relays this selfsame backstory to Johnny. You’d never guess it, if you were a moron, but Caretaker turns out to be the original Ghost Rider. And when Blackheart takes Roxanne prisoner in the town of San Venganza, Caretaker whistles for his horse, Johnny whistles for his motorcycle, and both, in defiance of the movie’s internal logic, and without seeming pain, burst into flame-skulled ghost riders and ride across the Texas plains together as “(Ghost) Rider of the Sky” plays on the soundtrack.

Wait, it gets better. At the outskirts of San Venganza, Caretaker suddenly pulls up. He says adios. He says, “I could only change one more time and I saved it for this.” For ... the ride? Why didn’t you save it for the fight? Wouldn’t that have made more sense? Seriously, dude, pull your head out of your ass.

I admit I’m no fan of this character. Ghost Rider gets his powers from the ultimate source of evil yet somehow isn’t controlled by that evil. There should be this ongoing tension between Johnny and the Devil, this “Devil and Daniel Webster” brand of one-upmanship, but we never get that. We don’t get close to that. Instead, we get exchanges like this:

Johnny: I sure wish things could’ve turned out different.

Roxanne: No. This is what you were meant to be.

Cool, schlock, whatever. Did they have to make it so blisteringly stupid?

Monday December 05, 2011

Movie Review: Katyn (2007)

WARNING: SPOILERS

At the start of “Katyn,” a Polish drama about the massacre of 20,000 Polish officers in the Katyn forest in 1940, a group of refugees fleeing the German invasion in September 1939 wait for a train to pass and then set off across a bridge to what they think is safety. Halfway across, they meet another group of Polish refugees fleeing the Soviet invasion. Each warns the other group that they’re going the wrong way. A succinct dramatization of the Polish dilemma.

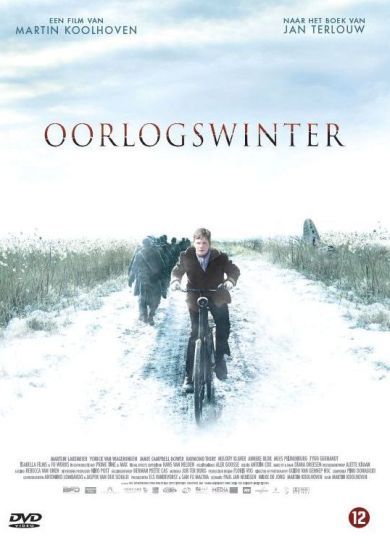

Unfortunately, melodrama has become the lingua franca of foreign movies dealing with unspeakable, World War II-era horrors. So it was with the rape of Nanjing in both the Chinese film “City of Life and Death” and the German film “John Rabe.” So it was with the Vel’ d’Hiv round-up of Jews in Nazi-occupied France in “La rafle” and in “Oorlogswinter,” that bildungsroman of Nazi-occupied Holland. And so here.

“Katyn,” directed by Andrzej Wajda, was nominated best foreign language film at the 2007 Academy Awards, (it lost to “The Counterfeiters”) so I guess I expected a lot. Or more.

From the refugees on the bridge, two faces emerge: Anna (Maja Ostaszewska) and her daughter Nika (Wiktoria Gasiewska). They’re rushing toward the Soviet side to find Anna’s husband, Andrzej (Artur Zmijewski), a Polish military officer; but the closer they get, the worse the news. The Uhlan, the Polish cavalry, is no more. The invasion is over. Poland is taken. Soldiers captured by the Soviets are let go but officers remain POWs. She arrives at a camp, looking no worse for wear, only to see doctors operating on the wounded, an INRI crucifix missing its Christ, and rows of dead. It’s Nika who spots daddy’s coat with the blue ribbon on it. It’s draped over a body, where a priest is administering last rites. With a trembling hand, Ann removes it and finds the missing statue of Christ. This prefigures future mix-ups involving corpses and clothes but one still wonders why the priest was administering last rites to a statue. A ruse? Was he hiding the Christ figure from the Soviets? I assumed they knocked the figure off its cross but maybe he did to save it.

From the refugees on the bridge, two faces emerge: Anna (Maja Ostaszewska) and her daughter Nika (Wiktoria Gasiewska). They’re rushing toward the Soviet side to find Anna’s husband, Andrzej (Artur Zmijewski), a Polish military officer; but the closer they get, the worse the news. The Uhlan, the Polish cavalry, is no more. The invasion is over. Poland is taken. Soldiers captured by the Soviets are let go but officers remain POWs. She arrives at a camp, looking no worse for wear, only to see doctors operating on the wounded, an INRI crucifix missing its Christ, and rows of dead. It’s Nika who spots daddy’s coat with the blue ribbon on it. It’s draped over a body, where a priest is administering last rites. With a trembling hand, Ann removes it and finds the missing statue of Christ. This prefigures future mix-ups involving corpses and clothes but one still wonders why the priest was administering last rites to a statue. A ruse? Was he hiding the Christ figure from the Soviets? I assumed they knocked the figure off its cross but maybe he did to save it.

At the POW camp, we finally meet Andrzej and his more cynical companion Jerzy (Andrzej Chyra). Andrzej is planning on writing down all that happens, recording it for posterity, while Jerzy feels things are more ominous than that:

Jerzy: The future is bleak.

Andrzej: Meaning?

Jerzy: The Soviets haven’t signed the Geneva Convention.

We get a few good, short conversations between the two. When Andrzej mentions that tanks can be rebuilt but trained officers are irreplaceable, Jerzy responds, “I hope the Soviets don’t realize that.” His best, truest line comes shortly thereafter: “Buttons. That’s what will be left of us.” But these conversations don’t build toward anything. Andrzej is honorable and attentive; Jerzy foresees doom. For good friends, they have little to talk about.

In the camp, which is not yet fenced in, Anna sees him, goes to him, cries. She begs him to flee with her in the confusion, but he refuses and winds up shipped to a Soviet camp. She and Nika, meanwhile, are trapped on the Soviet side. One wonders what she was doing in the first place. Who drags a six-year-old across half of Poland, in the middle of a war, to find a military officer?

The German side isn’t any better, of course. In November 1939, in Krakow, Andrzej’s mother (Maja Komorowska ) urges her husband, Jan (Wladyslaw Kowalski), a distinguished-looking university professor, mulling over clippings of his handsome son, to refrain from a university meeting with the S.S. But, as with the son, he does the honorable thing and stands by the chancellor during what he imagines will be a conversation with the Germans. But there is no conversation. The Poles are chastised for opening the university without permission and sent to the Sachsenhausen camp, where Prof. Jan dies of cardiac arrest.

So it goes. Characters are perfunctorily introduced only to die or disappear. Anna escapes from the Soviets with the help of a Russian captain (who has something of Tommy Lee Jones’ sad gaze about him), but then he’s off to the Finnish front. Dasvidania. Anna and Nika make it back to Krakow no worse for wear. There, the General’s wife, Roza (Danuta Stenka), gazes out windows, her stylish hat cocked at an angle.

Then suddenly it’s 1943 and Roza is ordered by the Germans, now at war with the USSR, to denounce the Soviet massacre of Polish officers in the Katyn Forest; but, even after seeing horrific footage, she refuses to be used for Nazi propaganda purposes.

Then suddenly it’s 1945, Poland belongs to the Soviet Union now, which claims that the Katyn massacre was a German operation in the spring of ’41, not a Soviet operation in the spring of ’40, and to say otherwise means death. Even so, Roza says it in the town square (“It’s a lie”), where names of the Katyn dead are read through a tinny loudspeaker. Jerzy, who has survived, pulls her away but she shows no gratitude and accuses him of being just like the Soviets. Off she goes into the fog. And in he goes to a bar, where he gets drunk and speaks the truth, then walks out into the night and shoots himself in the head. Do widzenia.

Other characters emerge. Tadeusz (Antoni Pawlicki) is an enthusiastic student whose father died at Katyn and he gets in trouble for tearing down a Soviet propaganda poster. Pursued through the streets of Krakow, he’s aided by Ewa, whom we saw earlier (on the bridge?), but who is now all grown up ((Agnieszka Kawiorska). The two talk movies, plan on meeting the next night at the local theater, share a kiss, but upon departing Tadeusz runs into the pursuing Soviet officers, who chase him into oncoming traffic. Do widzenia.

Meanwhile, Agnieszka (Magdalena Cielecka), of the long blonde hair and the hard, world-weary look, has her hair cut to pay for a tombstone for her brother, another Katyn victim, but includes the year, 1940, making it a Soviet massacre, and for that .... Do widzenia.

Finally, Ann receives Andrzej’s diary, and we get the massacre, which is horrific, in flashback.

These last scenes are powerful but by this point we’ve given up on the movie. I like some aspect of it in theory—characters introduced just to die, approximating the value of life in war and under totalitarianism—but the glue holding it together is still the stuff of soap opera: Anna crying across half of Poland, the cute kids kissing, Roza in her rakish hat gazing. The crime is a double crime: the massacre itself and then lying about it for decades; and the film is a reminder that, unlike western Europe, unlike the French or British or even the Germans, the Poles were not freed in 1945 but continued to live under an occupying force, an oppressive tyranny, for decades.

Even so, it’s a plain movie. Our unspeakable horrors—the Holocaust, the Rape of Nanjing, the Katyn massacre—deserve better.

Tuesday November 22, 2011

Movie Review: Hulk (2003)

WARNING: PUNY SPOILERS

The Hulk is the ultimate fantasy figure of the weak and average. One moment he’s a normal dude, Bruce Banner, a scientist; the next moment, he’s a huge, muscle-bound, inarticulate rage machine that can destroy anything in front of him. He is rage personified. He is how we like to envision our own rage. We like to move through the world thinking, “Don’t make me angry; you wouldn’t like me when I’m angry,” when, let’s face it, almost no one is scared if we become angry. Our rage is generally impotent. We destroy nothing in front of us.

So if you’re going to create a movie that taps into the Hulk fantasy, under what circumstances would you have Bruce Banner hulk out? When provoked by bullies? Criminals? Authority figures?

Here’s what causes Bruce Banner (Eric Bana) to morph into the Hulk in Ang Lee’s “Hulk”:

- He thinks about stuff in his lab, then upends a janitor’s pail in the hallway.

- He gets into a fight with his nemesis, Glenn Talbot (Josh Lucas).

- He has a nightmare in a sleep-deprivation chamber.

- His father (Nick Nolte) turns into a giant electro-creature in front of him.

Only 2) comes close to what we want.

That’s not even the worst part. Here’s the worst part. Between incidents 2) and 3), Talbot, as battered as Evel Knievel after a bad jump, returns to provoke Banner again in the hope of finding out more about the Hulk gene. He tasers him—once, twice, five times. Then he decks him. Nothing. “Consciously you may control it,” Talbot tells Banner’s supine figure. “But subconsciously? I bet that’s another story.”

Consciously you may control it? The whole point of the Hulk is that you can’t control it. If Bruce Banner could control it, you wouldn’t even have a story.

I’m sorry to harp on this, but of all the stupid ways a modern superhero movie has deviated from the source material, this is one of the stupidest. I’d call it the second stupidest—right after the way filmmakers exonerated the Burglar for the murder of Uncle Ben in “Spider-Man 3” and thus ruined Spider-Man’s whole raison d’etre. Don’t get me started on that one.

I’m sorry to harp on this, but of all the stupid ways a modern superhero movie has deviated from the source material, this is one of the stupidest. I’d call it the second stupidest—right after the way filmmakers exonerated the Burglar for the murder of Uncle Ben in “Spider-Man 3” and thus ruined Spider-Man’s whole raison d’etre. Don’t get me started on that one.

I watched Ang Lee’s “Hulk” again recently with the thought that maybe we were all being harsh when we dismissed it back in 2003. It was the movie Lee made between “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” and “Brokeback Mountain.” How bad could it be?

Awful, it turns out. Horrible. Lee takes a fairly simple story and complicates it with angry, unforgiving fathers, a nothing romance, a non-entity for a protagonist, and zippy split-screens and quadruple screens, popular in 1960s art-house cinema, but here representative of comic panels. Except they just get in the way.

We begin in the mid-1960s with military scientist David Banner (Paul Kersey), against orders from Gen. “Thunderbolt” Ross (Todd Tesen), intent on manipulating the human immune system. After he experiments on himself, his wife tells him she’s pregnant. Oops. And yes, he passes the genetic modification on to his son.

The sins of the father grow worse. He treats little Bruce like a science experiment. He takes away his binky and watches his skin turn vaguely green when he bawls. WHAT HAS BEEN PASSED ON? he writes. He gives him monsters to play with then studies his blood. CONFIRMS MY WORST FEARS, he writes. Before he can cure him, though, Ross fires Banner for ignoring protocol, and in response Banner ... launches a gamma bomb? Is that right? How does a scientist get the authority to do that? And what does that green mushroom cloud have to do with anything? Is it to distract everyone so Banner can return home and kill his son? Instead he knifes the mother right in front of the son. “It was as if she, and the knife, merged,” the older, more bat-shit Banner (Nolte) says, later, in one of the film’s good lines. “You can’t imagine the unbearable finality of it.”

But Bruce, already a bottled-up child, represses the memory (we don’t see the knifing until the third act), gets adopted, and becomes a scientist like the crazy dad he doesn’t remember. We’re nearly 12 minutes in our seats, our popcorn nearly gone, before we see the adult Bruce shaving in his mirror, biking to work, and remaining emotionally unavailable to the best-looking scientist who ever walked the planet, his ex, and lab partner, Betty Ross (Jennifer Connelly at her most smoking). Yes, “Thunderbolt” Ross’ daughter. Small world.

Smaller world: They’re trying to improve the human immune system, too! Just like David Banner! He killed a monkey in the process, they explode a frog or two. Then Banner’s assistant stumbles, sets off the gamma radiation, and Bruce purposefully takes the brunt of it. Cue muffled g-bomb explosion inside him. Nice effect, actually.

In the hospital, Bruce has two visitors: Betty, who cries, and complains, and doesn’t acknowledge his bravery (which would totally suck); and the new janitor with his crazy hair and mean dogs, who turns out to be Bruce’s biological and bat-shit dad (ditto).

For some reason—repressed memory of the killing of the mother?—Bruce gets really pissed off by the presence of bat-shit dad. In fact, back in the lab, it pisses him off so much he turns into a giant green monster. This occurs without any provocation from anyone and 42 minutes into the film. Talk about a downer.

It gets worse. The crazy father who wanted to save his son from genetic mutation has become the crazier father who wants to save the genetic mutation from his son. In this endeavor he sees Betty as an obstacle (he’s right: she can tame the Hulk) and so sics giant dogs, including a giant French poodle, on her. But Bruce hulks outs and battles them. Then in a quiet moment in her battered car, Bruce, not the Hulk, but Bruce almost chokes her. Nice. Is this why she betrays him to her father (now Sam Elliot), who locks him up? But Talbot’s dickish ways unleash the Hulk again, who escapes and goes bouncing around the American southwest pursued by army helicopters. He winds up in San Francisco, where the battle between a giant green creature and the U.S. military draws many onlookers, zero news cameras and one hot female scientist. When Hulk sees Betty, he goes from a huge, engorged creature to something small, limp, and vulnerable. It’s the anti-Freudian stance. Hulk is angry but innocent. The monster inside us is actually sweeter than we are.

This sets up the final, crazy showdown between the Banners, and the epilogue in Central America. “No me hagas enfadar; no te va a gustar cuando este enfadado.” These 30 seconds are the best part of the movie.

“Hulk” isn’t all bad. I like Bruce’s early admission to Betty, “You know what scares me the most? When it comes over me, and I totally lose control... I like it.” Connelly is good, too. Her flirtations with Bruce are fun, but they run into the blank wall of his character and dissipate.

Other than that, “Hulk” is an overlong, poorly edited, poorly directed, pointless mess. It wants to say something deep and winds up saying nothing.

Even the writing team of James Schamus (“Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon”), Michael France (“Goldeneye”) and John Turman (uh... “Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer”) disappoint. Early on, before anyone Hulks out, Talbot wants to buy (take over) Bruce and his research team. Bruce refuses. They lock eyes. Then they have the following exchange:

Talbot: You know, someday I’m going to write a book. And I’m going to call it ‘When Stupid Ideals Happen to Smart Penniless Scientists.’

Bruce: Wow, that’s a shitty title.

Talbot: No, the point is—

Bruce: Why not “Smart Scientists, Stupid Ideals”? Isn’t that simpler?

Talbot: Listen, I’m—

Bruce: You call yourself a businessman? You don’t even know how to sell anything.

Kidding. That’s my rewrite. Here’s how the scene really played out:

Talbot: You know, someday I’m going to write a book. And I’m going to call it ‘When Stupid Ideals Happen to Smart Penniless Scientists.’

Bruce, fuming, stares at Talbot, who leaves.

Erik smash.

Saturday October 15, 2011

Movie Review: Winter in Wartime (2008)

WARNING: OORLOGSSPOILERS

Have we reached the point where we can only view World War II through the prism of melodrama? Or do only melodramatic foreign-language films about World War II get released in the U.S.? See recent entries: “City of Life and Death,” “John Rabe,” “Le Rafle.”

See also “Oorlogswinter,” or “Winter in Wartime,” which is about a young Dutch boy, Michiel (Martijn Lakemeier), living in a small town in Nazi-occupied Holland. The movie begins in January 1945 so we know, as he doesn’t, that only a few months are left in the war. The Allies are coming. Just hold on, lie low, and you and yours will be fine.

He doesn’t lie low.

His father, Johan (Raymond Thiry, looking remarkably like Sam Neill), is the mayor of their small town—the “Burgermeister” in German (which unfortunately flashed me back to the old Rankin-Bass special “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” and its Burgermeister Meisterburger character). While the position has its privileges, it also has its responsibilities, which Johan takes seriously. He sees himself as a bridge between occupiers and occupied. He makes what friends he can with the occupiers in order to protect the occupied. Early in the film, Michiel, through binoculars, watches his father shake hands with German soldiers to protect neighbors. Michiel thinks him a weakling and a coward as a result.

His father, Johan (Raymond Thiry, looking remarkably like Sam Neill), is the mayor of their small town—the “Burgermeister” in German (which unfortunately flashed me back to the old Rankin-Bass special “Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town” and its Burgermeister Meisterburger character). While the position has its privileges, it also has its responsibilities, which Johan takes seriously. He sees himself as a bridge between occupiers and occupied. He makes what friends he can with the occupiers in order to protect the occupied. Early in the film, Michiel, through binoculars, watches his father shake hands with German soldiers to protect neighbors. Michiel thinks him a weakling and a coward as a result.

Little shit.

Seriously, can someone live half their life in occupied territory and still be such a little shit? It’s obvious what his father is doing. It obviously takes courage to do what he does. So we wait for this realization to come over Michiel. It takes most of the movie.

There’s also an uncle, Ben, Oom Ben (Yorick van Wageningen), who returns, bigger and larger than life, to stay with them. He lets Michiel take his suitcase up to the attic, where the boy rifles through it, finding evidence that Ben is with the resistance. At one point, he hears his uncle and father arguing over the matter. Ben wants to start a resistance movement in town; Johan is resistant. He doesn’t want to draw Nazi ire. Michiel can barely abide his father at this point.

My immediate thought: Since the boy is wrong about his father, might he be wrong about the uncle? Surely the uncle isn’t a Nazi collaborator. Surely it’s not one of those kinds of movies.

It’s one of those kinds of movies.

Pity. There’s some good stuff here. Michiel finds a downed Allied pilot, Jack (Jamie Campbell Bower), hiding out in the woods, and brings him food and information and eventually medical attention in the form of his good-looking older sister, Erica (Melody Klaver). Erica is infatuated but no less than Michiel. The film could be retitled “Winter of my British Soldier.”

Jack had killed a German soldier upon landing, or crash-landing, and when the German body is found the Germans take three prominent Dutch officials, including Johan, prisoner. The plan is to execute them unless the true culprit is found. Michiel, of course, knows the true culprit. But he’s been told by Ben that his father will go free; so even when Jack offers to give himself up, Michiel tells him, no, his uncle is handling it.

Except his uncle doesn’t handle it, and, at the last instant, Michiel bikes through the snow to stop the execution. Cue: people holding him back. Cue: Michiel running in slow motion. Cue the order given and the rifles blasting and the officials falling.

Oh, slow motion. How many movies have you ruined?

This should be what the movie's about. Michiel had the knowledge to save his father and didn’t. He even waived off Jack’s attempt to save his father. His father is dead now because of his actions. One wonders how he can ever tell his mother. One wonders how he can tell himself every day for the rest of his life. That’s a heavy weight for a kid to carry.

But we merely get a sense of that weight. Then the plot kicks in, Jack must be saved, Ben is brought in to help save Jack, etc. At one point, Oom Ben says something he couldn’t possibly know, unless ... Michiel rushes up to the attic, rifles through his suitcase again. Nothing. But wait: There’s a false bottom. His uncle is a Nazi collaborator. Cue another bike ride through the snow to try to save Jack and Erica from Ben’s inevitable betrayal.

“Oorlogswinter” is based upon a novel of World War II by Jan Terlouw, a Dutch scientist, politician and author, who would’ve been around Michiel’s age in 1945. He writes children’s books mostly, with various moral dilemmas, and “Oorlogswinter” is one of them. It was made into a mini-series for Dutch TV in 1975.

In most movies, people are what we think they are, but here they’re the opposite of what we think they are—or what Michiel thinks they are. Does anyone think this is a deep commentary on human nature? It’s the adolescent commentary on human nature. So Johan is really a hero, Ben is really a traitor, and the fat bike-shop owner, who has to sponge off the “Nazi” signs written on his shop, is really a loyal Netherlander. Some of the Germans are even nice. When Michiel falls through the ice, it’s a German soldier who pulls him out. When the wheel of a horse cart comes off, with Jack inside, it’s German soldiers who rush to fix it. The world is so complex that way.

Michiel keeps falling in the movie. He falls off his bike in the beginning and is captured by the Germans. He falls through the ice. The horse cart wheel comes off. And as he and Jack are escaping the Nazis on Caesar, Michiel’s horse, they fall in the woods, Caesar breaks his leg, and the horse must be put out of its misery. But Michiel can’t do it. Jack has to do it for him.

This sets up our end. Ben is exposed and tied to a tree. But while Jack is escaping, with Erica’s help, Ben sets himself free and walks off despite the gun in Michiel’s hand. Will Michiel use it? Will he kill his uncle? Oh, will he?

Cue: Slow motion.

Tuesday May 31, 2011

Movie Review: X Men: The Last Stand (2006)

WARNING: THREE-MAIN-CHARACTERS-ARE-KILLED SPOILERS

When he took over the reigns of the “X-Men” franchise, director Brett Ratner promised that he and screenwriters Simon Kinberg and Zak Penn would put nothing on screen that hadn’t first been in the comic books.

If so, they must’ve panned the entire “X-Men” oeuvre for stupid shit. Because that’s what’s on screen.

If so, they must’ve panned the entire “X-Men” oeuvre for stupid shit. Because that’s what’s on screen.

Here. These are the first words we hear. It’s 20 years ago, we’re in a nice suburban neighborhood, a car pulls up to the Grey household (1769) and Professor X and Magneto (Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen), emerge, airbrushed creepily, for this bit of exposition:

Magneto: I still don't know why I’m here. Couldn't you just make them say yes?

Professor X: Yes, I could, but it's not my way. And I would expect you, of all people, would understand my feelings about the misuse of power.

Magneto: Ah, “power corrupts” and all that. Yes, I know, Charles. When are you going to stop lecturing me?

Let’s take a moment to distill that conversation:

Magneto: Hey, do X.

Professor X: I don’t do X. You know that.

Magneto: I know you don’t do X. Quit lecturing me on how you don’t do X.

The movie keeps doing this. It keeps giving us supposedly intelligent people having inane conversations.

The storyline is fine. You could argue the storyline is an improvement. In the first movie, Magneto tries to turn all humans into mutants (a dumb idea, since he despised humanity), and here humans try to turn all mutants into humans (a smart idea, since humans fear mutants). Dr. Henry McCoy, the Beast (Kelsey Grammar), who is now Secretary of Mutant Affairs, arrives at Xavier’s school with the news. “A pharmaceutical company has developed a mutant antibody: a way to suppress the mutant X gene,” he says. “They’re calling it a cure.” Everyone in the room is appalled. Then Rogue rushes into the room:

Rogue (excited): Is it true? Can they cure us?

Professor X (resigned): Yes, Rogue. It appears to be true.

Storm (angry): No, Professor. They can't cure us. You want to know why? Because there's nothing to cure. [To Rogue] Nothing's wrong with you. Or any of us, for that matter.

The X-Men series is often seen as a metaphor for the civil rights movement, or for homosexuality, but this is where that metaphor breaks down. Black is black, gay is gay, but not every mutation is created equally. No one mentions this in the film but here would’ve been a good spot. When Storm gets in Rogue’s face, Rogue should’ve stared back, taken off a glove, grabbed Storm’s wrist; and while Storm gasped in excruciating pain, while her face got all veiny, Rogue should’ve said:

Rogue: I can’t touch anyone. Ever. Because this happens. Get it?

[Lets go and Storm collapses on the ground.]

Maybe if I could control the weather I wouldn’t want to be cured, either. But don’t tell me there’s nothing wrong with me.

Instead we get what we get. Magneto recruits from “the Omegas,” underground mutants who dress goth-style and sport tattoos as if they were disaffected suburban kids. They gather in woods for speeches and lead an assault on Alcatraz Prison, where the mutant, Leech, who is the source of the antibody (mutants temporarily lose powers around him), resides, bald, silent, and vaguely concerned. But Storm leads a team of six mutants (Wolverine, Beast, Colossus, Iceman, Shadowcat) to defend Alcatraz and beat back this army of mutants. It’s a good battle sequence, I’ll give Ratner that, but it doesn’t make up for the stupidity we’ve already been subjected to.

And that’s only one of the movie’s two main storylines. The other deals with the resurrection of Jean Grey (Famke Janssen) as the Phoenix.

We knew this was coming. If we’d read X-Men #s 101-108, in which Jean Grey dies and is resurrected as the super-powerful Phoenix, we knew this was coming.

What I didn’t know, since I stopped collecting comics soon after that adventure, and went on to, you know, Kurt Vonnegut and Philip Roth and E.L. Doctorow and Norman Mailer, was the huge powers of the Phoenix weren’t the result of her death/resurrection. Apparently she’d always had them. Thus that opening scene at the Grey household. Thus the conversation between Professor X and Wolverine after Jean’s body, along with Cyclops’ glasses, are recovered from Alkali Lake. Here’s what we learn in that 30-second conversation:

- When Jean Grey was a little girl, Professor X created a series of psychic barriers to make her think she wasn’t as powerful as she was.

- Because of this, she developed a split personality: the Jean Grey we’ve known for two films; and the superpowerful, superangry Phoenix.

- Professor X isn’t sorry he did this.

- He dismisses, belittles, anyone who questions him on the matter.

This is the tail-end of their conversation:

Professor X: She has to be controlled.

Wolverine: Controlled? Sometimes when you cage the beast, the beast gets angry.

Professor X: You have no idea. You have no idea of what she’s capable.

Wolverine: No, Professor. I had no idea what you were capable of!

Professor X: I had a terrible choice to make. I chose the lesser of two evils.

Wolverine: Well, it sounds to me like Jean had no choice at all.

Professor X: I don’t have to explain myself—least of all to you.

I don’t have to explain myself—least of all to you? Really? That’s the moral exemplar of this series? The man who didn’t want to misuse his powers in the opening scene? The teacher who wouldn’t even tell Wolverine his own story in the second film—who said, channeling Glynda from “The Wizard of Oz,” that Wolverine had to figure it out for himself? Least of all you? Wow.

When I first saw this scene, back in 2006, I assumed that this Professor X, spouting such idiotic dialogue, was a hologram, or maybe Mystique, or was being controlled by some nefarious force, and I remember being confused when the movie kept going on and on until it became clear, no, this was Professor X spouting such idiotic dialogue.

It would’ve been so easy to fix, too. Keep most of the above dialogue—I like the “Sometimes when you cage the beast” line, for example—but give us the mea culpa:

Professor X: I know, I know... Maybe if I hadn’t... But it seemed the only way... God help me, it seemed the only way.

Or scrap this conversation and give us the big reveal in a conversation between Professor X and Magneto:

Magneto (amused): Charles, you’ve always accused me of not living up to your moral standards. You’ve even accused me of evil. Now look at you. Your beloved protégée is a monster. You ... [smiles wider] ... are a Dr. Frankenstein. In trying to do good, you’ve done more evil than someone like me could hope to do in a lifetime.

Instead we get what we get.

Don’t even get me started on the loutish dialogue between Rogue and Bobby (“You're a guy, Bobby; your mind's only on one thing”) or Mystique’s awful lines (“I don’t answer to my slave name”), or how Jean kills both Cyclops and Professor X—really kills them—and then just hangs back, crackling with power, as battles rage, or how Magneto, normally a smart man, sends mutants to kill Leech when their powers won’t work around Leech, or how the good X-Men neutralize Magneto with the mutant antibody, rather than Jean, who’s much more dangerous, or...

“X-Men: The Last Stand” posits Jean Grey as the most powerful, destructive mutant in the Marvel universe, but surely that title belongs to director Brett Ratner. He took a popular series, gave everyone stupid lines, killed off the main characters, then smiled like a chubby three-year-old expecting accolades. What a surprise for him when the world turned angry.

Or is there someone else? Someone more powerful and nefarious? The first two “X-Men” movies, in 2000 and 2003, helped reboot the superhero genre. Since then, the studio that produced and distributed them, Fox, has given us the following: “Daredevil,” “Elektra,” “Fantastic Four,” “X-Men: The Last Stand,” “Fantastic Four 2: Rise of the Silver Surfer,” and “X-Men Origins: Wolverine.” So maybe Fox is our most powerful and destructive supervillain. The corporation that would make idiots of us all.

Death of a franchise.

Friday May 27, 2011

Movie Review: X2 (2003)

WARNING: ONCE AND FUTURE SPOILERS

Does any superhero movie have as many good scenes as this one? Let’s count ’em off:

- In the opening, Nightcrawler (Alan Cumming), to the pulse-pounding grandeur of “Dies Irae” from Mozart's Requiem in D Minor, poofs in and out of existence, climbs walls, swats secret servicemen with his tail, and comes within seconds of killing the President of the United States with a knife on which a note is tagged: MUTANT FREEDOM NOW!

- The forces of William Stryker (Brian Cox) lead an assault of Xavier’s School for Gifted Children, in which most of the students, even those with powers, flee, but Wolverine (Hugh Jackman), the lone adult in the joint, takes out half the special forces. Snkt!

- Magneto (Ian McKellen), incarcerated in a plastic prison, discovers that—thanks to his partner-in-crime, Mystique (Rebecca Romijn)—his slovenly and brutish guard, Laurio (Ty Olsson), has metallic particles in his bloodstream. But what can Magneto do with a little metallic dust? Everything. He levitates Laurio, pulls the particles out of him—killing him painfully in the process—and manipulates the dust into three small metal balls with which, zinging and pinging like bullets, he destroys his plastic prison. Then flattening one metal ball into a platform, he rides it out of his prison while the other two orbit around him as if he were the sun. Brilliant.

- The cops surround the house of the family of Bobby Drake (Shawn Ashmore), called there by his brother, Ronnie, and proceed to shoot Wolverine in the head, and order the others, Bobby and Rogue (Anna Paquin) and John (Aaron Stanford) onto the ground. Bobby and Rogue comply. John, also known as Pyro, doesn’t. Breathing heavily, looking at his hands, assessing the situation, he says, “You know all those dangerous mutants you hear about in the news? I'm the worst one.” Then he shows them.

As I was writing these scenes down, all favorites, I realized they have something in common. They are moments when mutants let loose; when they no longer hold their powers in check and instead strike back against an unjust world. In each, we, the weak, popcorn-munching audience, who deal with unjustness all the time in our day-to-day, get to thrill at seeing unbridled power used against 1) an unjust government, 2) an unjust army, 3) a sadistic guard, and 4) an unjust world—a world where brothers turn you in to the cops and the cops shoot first and ask questions later.

What else do they have in common? They all involve either a hero who’s almost a villain (Wolverine), a hero duped into villainy (Nightcrawler) or actual villains (Magneto, Pyro). They don’t involve the main X-Men heroes: Professor X (Patrick Stewart), Storm (Halle Berry), Jean Gray (Famke Janssen) and Cyclops (James Marsden), our first, fourth, fifth and sixth-billed stars.

Why? Because these characters are dull. Dull dull dull. Professor X was always dull. Cyclops, too. It’s a problem as old as Milton’s “Paradise Lost,” in which Satan is a fascinating character and God is a bore. But does it have to be so? Professor X has the power to kill everyone on the planet with his mind. We see this power utilized in the film. So how about giving us some of that tension, the weight of that awful power, instead of Patrick Stewart’s bland benevolence?

I remember Storm having a fascinating backstory as a pickpocket in the “X-Men” comic books. That backstory was blown off in “X-Men” and only vaguely alluded to here. On the X-Jet, Storm goes back into the hold to try to draw out their new companion, Nightcrawler, whom they’ve picked up in a run-down church in Boston, and they have the following conversation:

Nightcrawler: You know, outside the circus, most people were afraid of me. But I didn't hate them. I pitied them. Do you know why? Because most people will never know anything beyond what they see with their own two eyes.

Storm: Well, I gave up on pity a long time ago.

Nightcrawler: Someone so beautiful should not be so angry.

Storm: Sometimes anger can help you survive.

Nightcrawler: So can faith.

When I first heard this conversation, in movie theaters in 2003, I thought Storm was implying that feeling pity was beneath her, that she had a larger spirit than that. No. She’s actually saying “Pitying humans is too good for them.” But that’s backwards. When you’re angry with someone it’s because they’re not living up to a certain standard you expect. When you pity someone it’s because they’re not living up to a certain standard ... and you know they never will. You’ve given up on them. Plus her anger, her contempt, comes out of nowhere, as if the filmmakers suddenly realized, “Oh yeah, Storm,” or as if Ms. Berry, post-Oscar, demanded a bit more screentime and wound up with this. But she doesn’t sell it. She never seems angry. She never seems Storm. She just looks slightly sad and way, way beautiful.

Storm. Angry. So angry.

And, hey, is Nightcrawler really implying that most people only know what they see because they don’t have faith? As if most people around the world don’t believe in something unseen? As if most don’t believe in God?

Despite that, and despite “X2”’s loutish, truncated title, designed to appeal to all the exxxtreme dudes playing their Xboxes and watching “XXX,” it’s still a great superhero movie, not only for the scenes above but for the quiet moments before the scenes above. It luxuriates in the language and embraces the mystery. I’m thinking Wolverine and Bobby in the kitchen before the attack; Wolverine and the cat in the Drake household; Rogue looking at Bobby’s old room in the Drake household; and Bobby’s “coming out” conversation with the Drakes (“Have you tried ... not being a mutant?”). There’s that beautiful visual, Bobby’s ice wall coming between Wolverine and Stryker, and the two men, seeing the shadow of the other on the other side, putting their hands on the wall.

I’m a fan, in particular, of the conversation between Magneto and John/Pyro on the X-Jet hurtling toward Alkali Lake. John begins poorly, dissing Magneto’s helmet. Then we get this:

Magneto: What's your name?

Pyro: [staring at his lighter in Magneto's hands] John.

Magneto: What's your real name, John?

Pyro: [summons lighter's flame to his hand] Pyro.

Magneto: Quite a talent you have there, Pyro.

Pyro: I can only manipulate the fire. ... I can't create it.

Magneto: You are a god among insects. Never let anyone tell you different.

It’s that last line. The way McKellen sells it. The scene is our first indication of Magneto’s recruitment technique. What does Professor X offer young mutants? Sanctuary. Safety. Companionship. Tutorial. He helps mutants control their powers, tamp them down. Magneto offers the opposite. All that power you feel within you? Let it loose.

“You are a god among insects. Never let anyone tell you different.”

How does Magneto not have more acolytes? And shouldn’t there be a greater tension between the two camps? Young and scared, they flock to Professor X, but as they mature, as they come into their own, as they abandon the need for safety for the need for power, how can they not throw off the bland father figure, Professor X, for the completeness, the absoluteness, and the absolution Magneto offers? You are a god among insects. Who wouldn’t want that?

So if “X-Men,” the first movie, was about learning and combating Magneto’s plan to turn humans into mutants, “X2” is about learning and combating William Stryker’s plan to kill all mutants via Cerebro and a duped Professor X—who, despite his monumental psychic powers, never seems to see it coming. The final big battle takes place in an old military facility beneath Alkali Lake in British Columbia, and it is, well, a final big battle, with many moving parts, which director Bryan Singer handles well. But I’m a little tired of final big battles. You know there’ll be this, and that, and in the nick of ... and the final escape as ... and then (whew) safety. Did we all make it out OK? Here, Jean doesn’t. But anyone who knows the “X-Men” series knows she’s not just Jean Grey; she’s the Phoenix.

Is it a coincidence that all three patriarchs in this movie—Professor X, Magneto, Stryker—have powerful female sidekicks? Of course Stryker’s sidekick, Lady Deathstrike (Kelly Hu), is there against her will, making her death at the hands of Wolverine all the more poignant. I guess Professor X’s sidekick, Jean, is there against her will, too, isn’t she? We find that out in the next movie. Only Magneto’s lady is hanging with him because she wants to. Let’s hear it for the villains.