Movie Reviews - Silent posts

Thursday June 06, 2019

Movie Review: The Phantom of the Opera (1925)

WARNING: SPOILERS

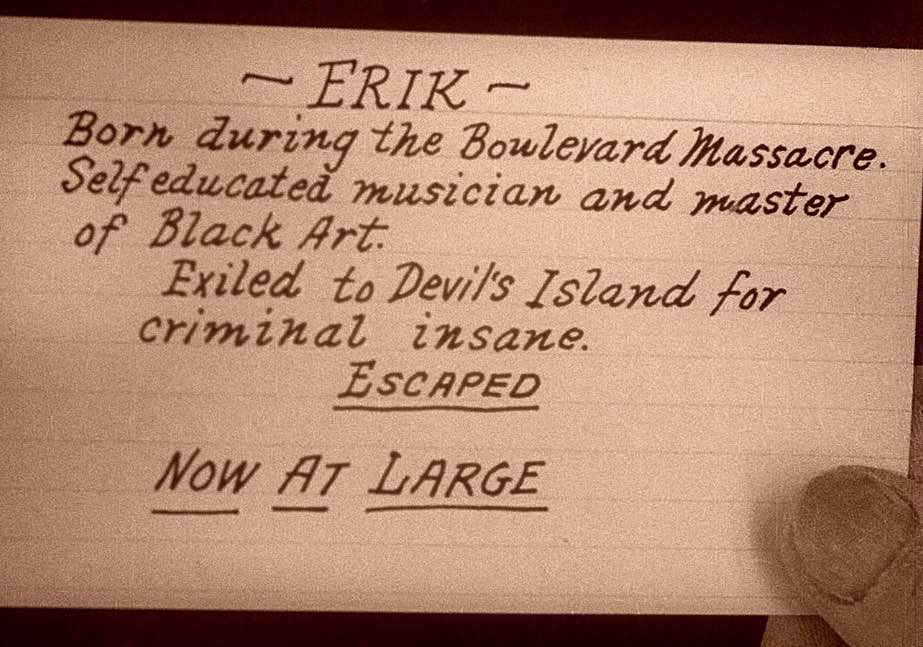

Here’s something I never knew until the 2019 Seattle International Film Festival: the Phantom of the Opera’s real name is Erik. With a k. And the name keeps coming up in the 1925 movie: in title cards, on a file card, in letters to Christina:

You’d think someone would’ve told me this at some point. Or that I would’ve figured it out on my own. Is it in the Andrew Lloyd Webber musical, for example? In any of the songs?

The

PhantomOfTheOpera

Is really Erik

With a kaaayyyy

I guess I didn’t really know the story, either, but it’s basically another of the deformed man/beautiful woman pieces. Think of Victor Hugo’s “Hunchback of Notre Dame” as hazy antecedent and Alan Moore’s “V for Vendetta” as direct descendant.

There are also elements of the Joker: the madman who’s somehow super organized.

Questions

So has anyone read the novel? Apparently what the ’25 version gives short shrift to is how long Phantom/Erik (Lon Chaney) has been tutoring his love, Christine (Mary Philbin). In the movie, every time he took credit for her talents I was like, “Bit presumptuous, dude.” But in the book that’s what happens. He makes her. Like Frankenstein. Or Eliza Doolittle.

So has anyone read the novel? Apparently what the ’25 version gives short shrift to is how long Phantom/Erik (Lon Chaney) has been tutoring his love, Christine (Mary Philbin). In the movie, every time he took credit for her talents I was like, “Bit presumptuous, dude.” But in the book that’s what happens. He makes her. Like Frankenstein. Or Eliza Doolittle.

In 19th-century Paris, two men buy the Paris Opera, while the sellers give each other sly looks. After the deal is made, they confess to the whole ghost/phantom problem, which is an odd move: “Hey, here’s how we snookered you!” Our new guys dismiss the rumors out of hand, but investigate a supposed phantom who sits in a regular balcony seat. At first they see him ... and then they don’t! So was this the Phantom/Erik? Did he have season tickets?

There are various backstage—or below stage—antics involving rumors of the Phantom, a stagehand who’s seen him (“a living skeleton”), and long shadows cast. The Phantom also sends threatening notices demanding casting changes. Specifically he wants Christine to star as Marguerite in “Faust” rather than the prima donna, Mme. Carlotta (Mary Fabian). And he gets his wish! Carlotta falls sick. Did the Phantom cause this? And could I do something similar with the Seattle Mariners? Send messages to management? Start So-and-So at short ... or else!

Meanwhile, Christine’s beau, Vicomte Raoul de Chagny (Norman Kerry), hears that he’s being superseded and confronts her about it. She admits she’s being tutored by someone she calls “the Spirit of Music,” and that nothing can stop her career now, but when he suggests she’s being duped she storms off. Later, outside her dressing room, he hears the Phantom talking to her: “Soon, Christine, this spirit will take form and will demand your love!” She's OK with that; she calls him “Master.” Kind of kinky. When she leaves, the Vicomte bursts in, but of course the room is empty.

Here’s a question the movie doesn’t really answer: Why did the Phantom choose Christine? Because he was enamored of her looks, her talent, or both? If it’s looks, wasn’t she a bit young when they started? And how did he become such an expert music tutor? I know: “self educated musician.” But that doesn’t mean you’re going to be a good teacher. Particularly if you’re, you know, insane.

Anyway, Christine’s debut goes well, but Carlotta returns to the role against the Phantom’s wishes, so for the next performance a giant chandelier crashes onto the audience. This is when the masked Phantom finally appears before Christine, and, in a kind of nightmare sequence, leads her slowly down the stone steps as she cowers in fright. What happened to all the “Master” talk? Hey, I thought you were into this!

There’s a labyrinth beneath the opera house, I believe she rides a horse for a time, and then he rows her via gondola across an underground river to his hideout. He wants to marry her, or something, says she can come and go as she pleases, but he makes one demand: that she never remove his mask. So of course that’s exactly what she does.

Apparently Chaney, who was already legendary in 1925, and only lived until 1930, did his own makeup. Even 100 years later it’s good. Spooky. One can only imagine what 1925 audiences thought.

So what’s her punishment for Eve-like doing the one thing she wasn’t supposed to? Erik says he’s going to make her a prisoner forever. But then he immediately lets her go back to the surface to say her goodbyes. Does she flee Paris? France? Does she go to the cops? None of the above. She attends a masked ball at the opera house, where she tells Raoul all; but the Phantom is there, too, spying, along with another mysterious, menacing figure in a fez, who turns out to be a cop, Ledoux. He's long been on the trail of the Phantom—a madman who escaped from Devil’s Island.

Another question: Was he a madman before Devil’s Island or was he tortured into it? And was his skeletal visage the result of the torture or was he born that way?

The big third act involves the Phantom kidnapping Christine off the stage, Ledoux and Raoul in pursuit but falling into one trap after another, and a mob with torches descending in the basement labyrinth of the opera house. There’s a chase through the streets of Paris, and the Phantom, grinning all the while, almost gets away but is caught near the Seine. I love the bit where he threatens the crowd with an explosive device in his hand, but then reveals the hand to be empty. I like how he does this—triumphantly—even though it means his doom. He’s beaten by the mob and tossed into the Seine. That’s it. Bye, Erik.

Stage 28

So what to make of this story? Why does it endure? How is it romantic?

To me, two things are still great about this ’25 version: Chaney, who apparently hated the director, and the sets. Here’s Wiki on the latter:

Because it would have to support thousands of extras, the set became the first to be created with steel girders set in concrete. For this reason it was not dismantled until 2014. Stage 28 on the Universal Studios lot still contained portions of the opera house set, and was the world's oldest surviving structure built specifically for a movie at the time of its demolition. It was used in hundreds of movies and television series.

One wonders which movies and TV series. One wants a book on the subject: “Stage 28.”

I got to see “Phantom” at SIFF, on the big screen, with a live soundtrack by Austin indie band The Invincible Czars. Made for a good Saturday afternoon.

Someone get back to me on the romantic question.

Friday January 04, 2019

Movie Review: The Perils of Pauline (1914)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Well, “spoilers.” If you haven’t seen it yet, that’s kind of on you.

I doubt many people who are alive have seen the original “Perils of Pauline,“ but most everyone knows the title. It’s part of the culture. It was a huge hit that propelled the career of Pearl White and made serials a staple for decades. And it introduced us to the term “cliffhanger,” even though the serial doesn’t have traditional cliffhangers. Chapters don’t end with Pauline yelling, “Help! Help help!”; they end happily for the heroine, with the villain thinking “Curses, foiled again!” But Pauline hung from a cliff in one episode, and the name stuck.

It’s been remade several times—in 1933 and 1967—but I think I was introduced to the concept via the 1969 Saturday morning cartoon show “The Perils of Penelope Pitstop,” whose plot, unbeknownst to me, was taken directly from the 1914 original: Pauline’s legal guardian keeps trying to kill her so he can get her money. You know: the usual kids fare.

It’s been remade several times—in 1933 and 1967—but I think I was introduced to the concept via the 1969 Saturday morning cartoon show “The Perils of Penelope Pitstop,” whose plot, unbeknownst to me, was taken directly from the 1914 original: Pauline’s legal guardian keeps trying to kill her so he can get her money. You know: the usual kids fare.

Pauline also remains oblivious, not to mention incurious, as to who is trying to kill her. She’s a bit of a dim bulb. That’s one of the annoying things about Pauline.

Actually, there are many annoying things about Pauline.

Tom and Daisy

I mention “the 1914 original” but that’s not quite correct. When “Pauline” was released in the U.S., it was 20 chapters long. A shortened nine-chapter version then made its way through Europe in 1916. That’s the one I watched because it’s the only one that still exists. Imagine that. Europe suffered two world wars but managed to hold onto someone else's movie history; we, uninvaded, lets ours slip through our grasp. World wars are nothing next to a disposable culture.

The plot is simple. Harry (Crane Wilbur), the son of a rich man, wants to marry his father’s ward, Pauline (Pearl White), but she begs off, wishing first for “a life of adventure.” So the rich man, Sanford Marvin (Edward José), promises her an inheritance, then puts his secretary, Koerner (Paul Panzer, who looks a bit like Rod Blagojevich), in charge of it. When she and Harry marry, she‘ll get the dough. Or he will.

Of course, Koerner—who was originally called Raymond Owen but became Germanic in France during WWI—isn’t who he appears to be. From the title card:

“Koerner, a man with a tainted past, has wormed his way into a position of confidence as Mr. Marvin’s secretary.”

I love the insinuation: His past is tainted so he’s automatically untrustworthy in the present. And he hasn’t done a good job as secretary; he’s wormed his way in. Was he already thinking nefarious deeds? Initially, he just seems like a guy doing his job. But then an old comrade, the evil Hicks (Francis Carlyle), shows up and blackmails him. Then the old man dies, Koerner gets bupkis except trustee of Pauline’s estate, so Hicks more or less whispers in his ear: “If you can manage to dispose of her, you’ll gain control of all her property.”

Hicks sets everything in motion, but, oddly, he’s not around for long. Each chapter begins with a new plot to kill Pauline but increasingly it’s only Koerner doing the plotting. And in the end, only Koerner finds his just desserts. Hicks? I don’t recall seeing him after the third chapter.

So what exactly are the perils of Pauline? She’s...

- trapped in a runaway balloon

- bound and gagged in a burning house

- bound and gagged in a flooding basement

- kidnapped by bandits, then Indians, then made to undergo “the race of the Great Stone of Death”

- left alone on a boat with a bomb on it

- adrift on a boat used as Gunnery target practice

She also enters a motor race and a steeplechase, tries to fly in an airplane, and helps rescue a submarine from foreign sabotage.

There’s great irony throughout. The “life of adventure” she wants is mostly created by Koerner in his various plots to kill her. Of the above, she only initiates the motor race, the steeplechase, and the trip out West. Otherwise, she’s just hanging around the mansion, waiting. For what? Mostly to not marry Harry. I get the feeling she doesn’t really like him.

There’s great irony throughout. The “life of adventure” she wants is mostly created by Koerner in his various plots to kill her. Of the above, she only initiates the motor race, the steeplechase, and the trip out West. Otherwise, she’s just hanging around the mansion, waiting. For what? Mostly to not marry Harry. I get the feeling she doesn’t really like him.

Yet it’s mostly Harry to the rescue. He discovers the bomb on the boat and the snake in the flower basket. He rescues her from the burning house by riding up on a white horse (there’s that trope), and lassos her out of the way of a big boulder rolling downhill toward her (there’s that trope). After she manages to halt the runaway balloon by dropping anchor and then scaling down onto a rock cliff, Harry climbs up to meet her. She responds, “I’m dizzy, Harry. You’ll have to carry me down!”

Wait, I thought you wanted a life of adventure.

Both of them are kind of awful. With the plane, he delays her arrival on the airfield, which prevents her from flying with famed aviator Wilson Smith. Instead only he is killed—in a plane sabotaged by Koerner. No one blinks an eye. Neither she nor Harry wonder about all the attempts on her life. They’re like Tom and Daisy in “Gatsby”: careless people who smash up things and then retreat back into their money and vast carelessness.

It wouldn’t take Sherlock Holmes to figure it out, either: all evidence points to Koerner. He’s got motive—the money—and he’s the one forever suggesting these life-threatening escapades. In Chapter 5, “A Watery Doom,” a band of gypsies (yes) dressed as firemen (sure) tie a bound-and-gagged Pauline and Harry in a cellar, which is then flooded by a nearby river. They report back to Koerner: “All is over!” Does Koerner play it tight to the vest? Not exactly. He celebrates by arrogantly firing the butler: “I am the master here now and I no longer require your services!” So, when Harry and Pauline turn up alive, why didn’t the butler say anything? “You know Koerner fired me while you were gone. He said he was the master here. He seemed to think you were both dead.” Instead, oblivious to the end.

Make that oblivious past the end. In the final chapter, on Harry’s yacht, Pauline points to a motorboat and says, “Harry, I should like to go all alone for a short cruise.” She does but Koerner puts a hole in the boat. When she realizes she’s sinking, she bites her fist, then rows to the target practice boat. When she realizes it’s being shelled, she puts a note in the collar of her faithful dog (there’s that trope), who swims to the gunnery. Pauline is saved! Which is when Koerner finally gets his comeuppance. By Pauline? By Harry? Nope. Just some guy. He saw the sabotage, fights Koerner and tosses him in the water. We see Koerner clinging to a log; then he’s underwater and his hands are clawing the air (there’s that trope). Then the end.

That’s right; They never find out. Instead, Pauline just agrees to marry Harry, and the two live obviously ever after.

Tune in tomorrow

There’s a lot of racism, of course, Indians and gypsies and probably worse which didn’t make the French cut (see slideshow). In the Indian camp, at one point, Pauline is declared a “fair goddess,” which results in happy dancing and kowtowing. “Our deviner has predicted your coming,” a warrior tells her. “You are the white girl who was to spring forth from the ground to lead the warriors of our tribe to victory.” So there’s that trope.

I like the oddities that resulted from—I imagine—translating title cards from English to French back to English: a reference to Pauline’s “immoral” strength, for example. The balloon ride at Palisades Amusement Park is said to cost $500. That would be more than $12K today. Francs, right?

In his book, “Classics of the Silent Screen,” Joe Franklin says ”The Perils of Pauline“ is the film ”that put serials on the map.“ They‘re still on the map—just hidden. They were replaced by television in the 1950s, then rebooted as single features with A-production values by nostalgic directors like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas in the 1970s. That’s what ”Star Wars“ was, and ”Raiders of the Lost Ark.“ Our long national rollercoaster ride began here.

SLIDESHOW

Saturday June 18, 2016

Movie Review: The General (1926)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Does anyone else extrapolate beyond Hollywood endings?

I know Buster Keaton’s “The General” is a classic, voted the 18th greatest movie of all time by the American Film Institute, with only Chaplin’s “City Lights” (No. 11) ahead of it in the pure comedy category. And I know 1926 wasn’t exactly an enlightened time when it came to race, so the fact that our hapless hero is in effect fighting to preserve slavery, even if he is just trying to get the girl, well, I’ll let go of that.

But the ending? Keaton’s Johnnie Gray finally gets the girl and the uniform; he’s both honored and loved. And we get that great final shot of Keaton and the girl, Annabelle Lee of Marietta, Ga. (Marion Mack), sitting on the siderod of the titular train, kissing, as he keeps saluting passing soldiers at such a furious pace it’s as if he’s dismissing them. There’s almost an Army schmarmy vibe to it. It’s as if he’s saying “Make love not war” 40 years before that became a rallying cry.

But the ending? Keaton’s Johnnie Gray finally gets the girl and the uniform; he’s both honored and loved. And we get that great final shot of Keaton and the girl, Annabelle Lee of Marietta, Ga. (Marion Mack), sitting on the siderod of the titular train, kissing, as he keeps saluting passing soldiers at such a furious pace it’s as if he’s dismissing them. There’s almost an Army schmarmy vibe to it. It’s as if he’s saying “Make love not war” 40 years before that became a rallying cry.

But it’s still 1862. And he’s still wearing Confederate grays. “So he’s dead in three years,” I thought. “And at best she’s Scarlett O’Hara, at worst ‘A Woman in Berlin.’”

I know. Don’t extrapolate.

Comic imperatives, narrative imperatives

The story is built on misperceptions that would easily be cleared up if someone, anyone, would just say something. Ironic, given silent film.

Johnnie, we’re told, loves two things, his train and Annabelle Lee. and we see him wooing her in her front parlor in his usual fumbling fashion. Then Confederates fire upon a Union garrison at Fort Sumter, war is declared, and Annabelle’s father and brother immediately go to sign up. And what about you? Annabelle seems to indicate to Johnnie. It takes a second for the other shoe to drop. Oh, right, I’m supposed to be brave. I loved Keaton at this moment. For not going along.

Except then he does. He’s first in line to sign up, but the Rebs won’t take him. The officers behind the scenes feel he’ll be more valuable as a train engineer except nobody bothers to tell him this. Despite his persistence, they simply order him out, repeatedly, and out he goes, dejected, only to be greeted by Annabelle’s father and brother, who eye him the way Annabelle did: So? You signing up? And he doesn’t bother to tell them. They think he’s a coward. Annabelle does, too. Even when he tries to tell her, she doesn’t believe him.

A year later, her brother has medals (I thought of Bob Dylan’s “John Brown”), her father’s been injured (superficially), and she’s still ignoring Johnnie. Then his train is hijacked by Yankee spies, who plan on destroying the Western & Atlantic Railroad tracks between Atlanta and Chattanooga, Tenn., cutting off the South from needed supplies. (Needed to keep slavery going.) This is based on a historic incident, the Great Locomotive Chase, or the Andrews’ Raid, after James J. Andrews, a Kentucky civilian who concocted it. The hero for the South was the train’s conductor, William Allen Fuller, who, per Wikipedia, “pursued the train hijackers on foot, by handcar, and in a variety of other locomotives.”

And that’s Keaton. There’s a great balance here between the comic imperative to have Johnnie fumble and the narrative imperative to have him succeed, and Keaton threads it like the silent-film genius he is. It’s this element of the movie, oddly, that Mordaunt Hall, in his review in The New York Times in February 1927, found problematic:

It is difficult to reconcile one’s self to a hero who is apparently astute in some things and almost idiotic in others. This man, who has difficulty in crossing a road, is supposed to be crafty enough to outwit the Northern General.

Hall’s piece is titled “Mr. Keaton’s Face Overpowers This Film,” which most modern critics would agree with; but he also dismisses the film as “somewhat mirthless,” which, for most critics, is like shots fired at Fort Sumter.

Vicissitudes

I’m in the middle. Keaton does beautiful things onscreen but he doesn’t make me laugh like Chaplin. Chaplin is also gentler around women. There’s something petulant and vaguely menacing about Keaton at times. Example: As Johnnie and Annabelle work to bring back The General and save the South (temporarily), she keeps mucking up in ways different from his own. So he throttles her neck. Like she’s Laurel or something. I guess it’s EOE but it’s still a bit of a surprise, particularly given his parlor shyness. Beware the shy ones, girls.

Most of the movie is chase, and includes the most expensive scene of the silent era: a locomotive is sent over a burning bridge, which collapses and sends the train, a real train, into the river below. But its most famous shot is an early one: a heartbroken Keaton sitting on the siderods as the train moves again, taking him up and down as if on a merry-go-round, or, more aptly, on the vicissitudes of life. It’s exquisite. I also liked a moment in the North when Johnnie is hiding under a table where the generals are making their plans. A cigar burns a hole in the tablecloth, and for a moment we fear that Johnnie will be revealed. Nope. It’s so Johnnie can see Annabelle through the hole. It’s a natural iris shot. Lovely.

But 18th all time? In AFI’s first 100 greatest films list, from 1997, “The General” didn’t even make the cut. Anyone know what happened between 1997 and 2007 to give it such a boost?

Plus, fuck it I’ll say it, Johnnie is fighting to preserve slavery. That curdles some of the comedy for me.

Tuesday March 01, 2016

Movie Review: The Lime Kiln Club Field Day (1913)

Williams and Grey get ready for their close-up.

Last Monday, at the Paramount in Seattle, as part of “Silent Movie Mondays,” I saw a movie few people have ever seen.

It's called “Lime Kiln Club Field Day,” and no worries if you haven't heard of it. It was produced by the Biograph Company in 1913, and starred Bert Williams, a West Indian vaudeville performer who is considered the first black star (headlining shows on Broadway, for example, at a time of the KKK and lynchings in the South), but it was never released. And it would‘ve disappeared completely if, in 1939, the Museum of Modern Art hadn’t bought 900 cans of film that the bankrupt Biograph company was planning to destroy. “Lime Kiln” was among those reels; MOMA didn't know what it had until recently.

And why do we care? Because it's the first feature-length film with a mostly African-American cast. Williams is in blackface but no one else is. And as fraught as the concept of blackface is, within the confines of the film it feels like another comic mask—like Chaplin's moustache or Keaton's stone face. In the film, it doesn't feel racially derogatory. He's our clown, as Chaplin was. Indeed, one of the startling aspects of the film is how typically “silent film” it is. How long before we got another cinematic portrait of the African-American community that was this positive? Or this neutral? I'm guessing decades.

The plot is fairly simple. Williams is one of three men trying to court a girl, played by the super-stylish Odessa Warren Grey, and things begin to turn in his favor when he inadvertently drops a jug of gin down a well, tainting the water. He then labels the well “Gin Spring” and sells it, or something, and comes into cash. Then he escorts Ms. Grey through the fair, onto the rides (including an early 20th century Merry-Go-Round with brass ring), and to the big dance, where, I believe, he's revealed as a charlatan. No matter. He still gets the girl. The movie ends at her gate with a big kiss. Multiple versions of a big kiss, actually. Spike Lee would be proud.

If I sound shaky on some of the details it's because no title cards were ever created for the film, and no script was found. The curators at MOMA, including Ron Magliozzi who toured with the film, went so far as to hire lip readers to figure out what was being spoken. Most it was unhelpful ad-libbing. (After the screening, I asked Magliozzi what was being said, and he mentioned that in some scenes, such as when the rivals all show up at Ms. Grey's gate, they‘re actually swearing: “What the fuck are you doing here!” etc. Makes one wonder how R-rated silent films might actually be. Surely a good future project for someone.)

Even without the title cards, though, you pretty much know what’s going on. Indeed, their lack probably helps the film, since we do get title cards in the Bert Williams short, “Natural Born Gambler,” which precedes “Lime Kiln,” and they‘re rendered in the usual, minstrel-y fashion of the time: “de debbil” for “the devil.” To me, the title cards are more problematic than the blackface, which in some ways emphasizes Williams humanity rather than detracting from it. So it’s probably a net positive that “Lime Kiln” doesn't have the cards. It allows the story to be the story.

The most commented-upon aspect of the film is the cakewalk at the big dance. It feels like the first episode of “Soul Train” ever recorded:

After our screening, there was a discussion, moderated by Seattle Theater Group's marketing director Vivian Williams, and featuring Magliozzi; Teddie Gibson, who composed a score for the film and played on the Paramount's Wurlitzer organ; and Dr. Louis Chude-Sokei, a UW professor who's written a book about Williams, “The Last ‘Darky,’” which I would love to read someday when I don't have a stack of books to get through. I‘ve sat through a lot of these Q&As, and they’re usually death, but this one was great. It had history, disagreement, discussion, insight. I wanted it to keep going.

So why was the film never released? Magliozzi suggests that once “Birth of a Nation” was released in 1915, and became a huge hit, and the KKK reformed and everything, it didn't seem like a good idea. But that would mean they kept it in the can for two years? Did they do that with silent films? I'm guessing there's a different answer—one we'll probably never know.

Saturday August 02, 2014

Movie Review: Headin' Home (1920)

WARNING: SPOILERS

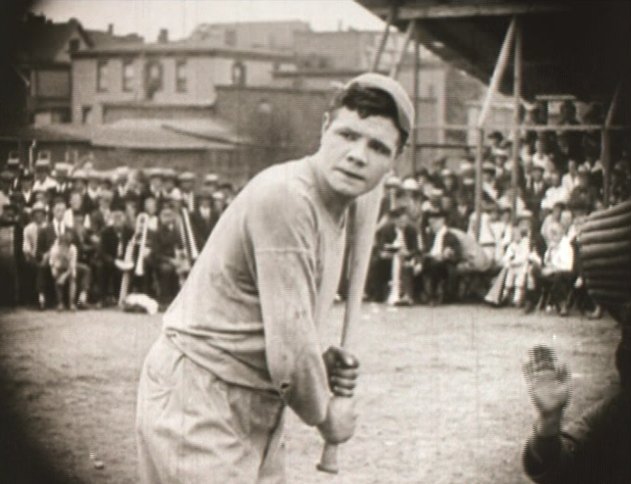

Did Bernard Malamud ever see this film? He was born in 1914, the movie came out in 1920, so it’s possible. Maybe it made an impression. Maybe it lodged in his unconscious.

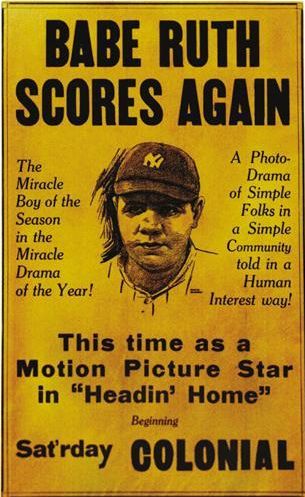

I initially assumed that “Headin’ Home“ was made in the flush after Babe Ruth’s 54-homerun season that made him a national sensation, but it was actually made after the 1919 season, when he first set the single-season record with 29 homeruns.That was enough of a big deal to make the film. Then he doubled his big deal to 54 homers as the film was released on Sept. 19, 1920. OK, he was actually stuck on 49 that day. The New York Times even talked about a slump the “Mauling Monarch” (a Ruth nickname I’d never heard before) was going through, and opined that Babe’s 50th “is still in the incubator, and it looks as if it wouldn’t be hatched for a while yet.” Four days to be exact. He hit 50 and 51 on Sept. 24.

Then he doubled his big deal to 54 homers as the film was released on Sept. 19, 1920. OK, he was actually stuck on 49 that day. The New York Times even talked about a slump the “Mauling Monarch” (a Ruth nickname I’d never heard before) was going through, and opined that Babe’s 50th “is still in the incubator, and it looks as if it wouldn’t be hatched for a while yet.” Four days to be exact. He hit 50 and 51 on Sept. 24.

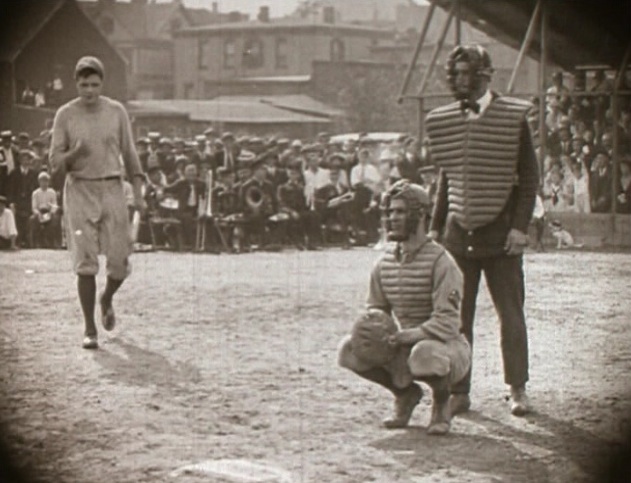

In the movie, Ruth plays “Babe,” a misunderstood but well-meaning country bumpkin from the small town of Haverlock. He lives with his mother, or “maw” (Margaret Seddon), his foster-sister Pigtails (Frances Victory, her only film), and their dog Herman. Simon Tobin (James A. Marcus), a banker, owns most everything in town, and he’s got a daughter, Mildred (Ruth Taylor), who’s pretty, and there’s a dog catcher and a local baseball team. The dog catcher is always after Herman and shakes his fist when he doesn’t catch him; the local baseball team is managed by the local barber, who’s Italian, eats garlic, argues with his wife, and doesn’t let Babe play. Instead, he and Simon hire a ringer, Harry Knight (William Sheer, his last film), who turns out to be both a rival for Mildred’s affections and a crook. He’s embezzling money from Tobin’s bank.

In the big game, Babe winds up playing for the visiting town, Highland (shades of the Highlanders, the Yankees’ original name), and in the 9th inning of a 14-14 tie, hits a towering homerun that breaks the window of a church five blocks away. Hero at last! Well, not quite. For this, the town almost lynches him. Then he winds up in New York and becomes a star, so they forgive everything. He marries Mildred after rescuing her from the clutches of Harry Knight, who winds up selling peanuts at Yankee Stadium. Haw haw on him. The End.

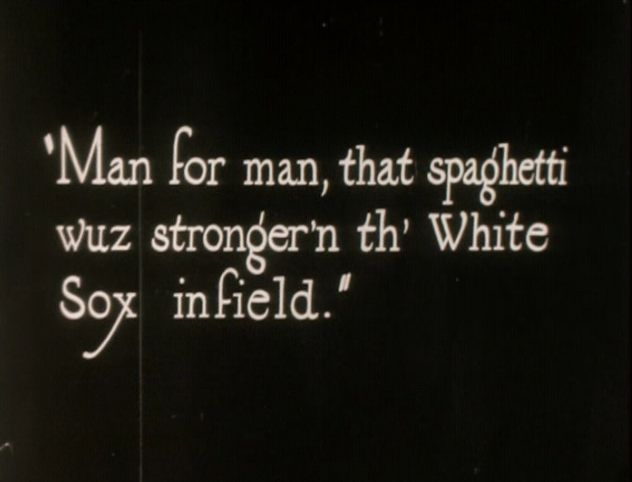

Two things are immediately interesting about “Headin’ Home.” The first is the title cards. Written by future Hearst journalist and humor columnist Arthur “Bugs” Baer, they are both archly homespun (dropped g’s, colloquialisms) and filled with sophisticated puns. It’s said, for example, that Ruth “made the Nation of Leagues forget the League of Nations,” while Haverlock is “a little egg and hamlet in the sticks.” Other examples:

SLIDESHOW: TITLE CARDS

More interesting, though, is whether “Headin’ Home” influenced the greatest fictional baseball story of all time, “The Natural,” published in 1952.

The first time we see Babe, he’s chopping down a tree. He spends half the movie whittling this tree into a bat, which he uses in the big game to hit his five-block homerun. He doesn’t call it Wonderboy, but right before he hits it, he looks over at Mildred in the stands. She doesn’t stand but she’s definitely urging him on. She’s the lady in white.

Again, who knows if Malamud even saw this thing (and if you know, let me know), but it’s interesting to contemplate. Maybe boys creating bats out of trees were already part of the early, Bunyanesque mythos of baseball that Malamud simply tapped into.

Ruth was hardly the first baseball player to star in a movie—Ty Cobb and Christy Matthewson had starred in some shorts: “Somewhere in Georgia” (1917) and “Matty’s Decision” (1914), respectively—but he was probably the first baseball player to star in a feature-length movie. “Headin’ Home” is five reels and 73 minutes long. Too long, to be honest. It wanders, it ignores Ruth’s rise in baseball, it makes villains of characters only to make victims of them (Si’s son, chiefly, whom Ruth rescues from a “vamp” in the final reel). It got good notices, even in The New York Times, but today it’s mostly interesting as a historical document. But in that it’s pretty interesting.

You know who’s interesting? Babe Ruth. He’s probably the best actor in the movie. You might even call him a natural.

SLIDESHOW: HEADIN' HOME

Thursday July 31, 2014

Movie Review: The Ball Player and the Bandit (1912)

WARNING: SPOILERS

In the Mariners heyday in the mid-1990s, when the Seattle newspapers would print just about anything Mariners related, I remember a short piece about the players and guns: how many they owned, etc. Baseball players tend to be a conservative lot, and many of them are country boys, so there were quite a few hunting rifles mentioned. Most ballplayers are rich, too, at least at the MLB level, and so a few of these guys had guns for protection. Except one: Randy Johnson—he of the 99 mph fastball. He said he didn’t have a gun in his house; he just kept a bucket of baseballs by his bed. If someone broke in ...

“The Ball Player and the Bandit,” a 1912 one-reeler directed by Francis Ford, John’s older brother, anticipated the Big Unit by about 80 years.

Harry Burns (Harold Lockwood) is a good pitcher with a university team whose uncle comes into a bad way financially and can no longer send him to school. He suggests Harry go west to find work.

It’s the usual fish-out-of-water scenario. He shows up in a suit, clutching a handkerchief, sneezing at the dust, and with an aversion to guns. All the cowhands give him looks. He gets a job as an accountant, but even the little Annie Oakley there (Helen Case, looking a bit like Carol Kane) pokes fun at him. He stifles some of this abuse by winning a fistfight with a rival, but he’s still not completely trusted. He doesn’t like guns? The hell?

But he’s still trusted enough to pick up the payroll in town. Unfortunately, he’s followed by the titular bandit—as well as the girl, who pretends to be a masked robber. Even as she’s quickly revealed by Harry, the bandit appears, dressed in black, gun drawn, and grabs the payroll. Then he feels in Harry’s pockets to remove him of his guns. Except there are none. He only finds a baseball, which Harry’s old coach had just sent to him. Laughing, he drops it and leaves. At which point Harry picks up the baseball and beans the bandit in the back of the head. He and the girl truss him up, bring him back, Harry’s the hero.

It’s not much of a story. But it is fun to come across a Hollywood movie that doesn’t glorify guns the way 99% of Hollywood movies do. Add it to the list, including “Destry Rides Again,” “To Kill a Mockingbird,” “Superman and the Mole Men,” and ... and ....

OK, 99.99%.

Friday July 25, 2014

Movie Review: His Last Game (1909)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The story is pretty simple. Choctaw has a big game against Jimtown, and they count on their star pitcher, Native American Bill Going, to lead the way. But gamblers enter the scene to fix the game. They try to bribe Bill with money. After about 10 seconds of melodramatic temptation, he turns them down. So they offer booze. Same deal. Finally, they attempt to get him drunk anyway by fixing him the era’s version of a roofie. But he outsmarts them, switches drinks, and then throws the booze-filled drink into the gambler’s face. A fight breaks out and the gambler draws a gun. It’s wrested away from him and he’s shot and killed. For this, Bill Going is led away by the authorities for murder. Well, “authorities.” “Swift western justice” the title card proclaims, and we next see him in front of an open grave, with the sheriff and a firing squad nearby.

But wait! A letter!

Deer Judge

If Bill Going wins this game, there’s new evidence in his favor and I demand a REPREEVE.

Signed by 604 of Arizona’s best cityzens an Yuba Bill, Sherif

Why is this new evidence going to surface only if he wins the game? Stop asking questions.

So the Choctaw chief stands in for Bill, who rides back to town, wins the game, and is about to celebrate with his teammates when he remembers the chief. Then he rides back and stands before the open grave. He asks for, and is granted, a pipe for a last smoke.

But wait! The Chief puts his ear to the ground and hears a coming horse! Maybe it’s a reprieve! No matter. The sheriff, standing behind Bill, signals for the firing squad to fire. They do, and Bill slumps into the grave ... just as, oh no, a man rides up with Bill’s reprieve! So sad!

C’mon, it was 1909. What do you expect—“Casablanca”?

People were obviously still learning the camera—or baseball—back then, as they tried to fit everything into the small frame. As a result, the ump stays off to the left rather than crouching behind the catcher, and it looks to be maybe 10 feet—rather than 90—between bases. Worse, when the catcher and ump aren’t in the frame, you have almost nothing in the foreground. Yet they didn’t move the camera for those shots. So the bottom third of the screen contains nothing while the top two-thirds contains everything—including a lot of characters who essentially have their heads cut off. It’s as if your grandmother photographed the movie on vacation.

IMDb is a bit sparse on the details behind the production, and Wikipedia is worse: only an Italian entry—so I’m not sure who made it or why or why they chose Native Americans. Did they think, “Hey, let’s mix westerns with baseball”? Or was the prevalence of Native Americans in early baseball—including Charles “Chief” Bender, a future Hall of Famer—a factor?

Italian Wiki claims that Harry Solter, a silent film director with several dozen credits, directed the thing, but IMDb simply leaves the credit blank. At the least, we know it was produced by Carl Laemmle’s Independent Moving Pictures Co. of America (IMP), which, in 1912, merged with several other production companies to form Universal Pictures, which is still one of Hollywood’s “Big Six” studios, having produced, among others, “The Sting,” “Jaws,” “E.T.,” “Jurassic Park,” and “Bridesmaids.” Laemmle’s first big success was “Hiawatha,” based on “The Song of ...” so maybe that’s the reason for the Native American focus.

“His Last Game” isn’t quite the first baseball story on film—that would probably be Edison’s “How the Office Boy Saw the Game” from 1906—but it is interesting as an historic artifact. Should we be surprised by its fairly positive portrayal of American Indians? Not according to Dave Kehr, who, in his review of “Reel Baseball: Baseball Films of the Silent Era,” writes, “The pro-Indian stance is quite typical for westerns, which have been caricatured for years as racist and genocidal, though I have yet to find an early one in which those sentiments were not placed in the mouths of villains.”

SLIDESHOW

Friday February 12, 2010

Movie Review: Robin Hood (1922)

WARNING: YOU’VE HAD NEARLY A CENTURY TO SEE IT, SO DON’T EVEN TALK TO ME ABOUT SPOILERS.

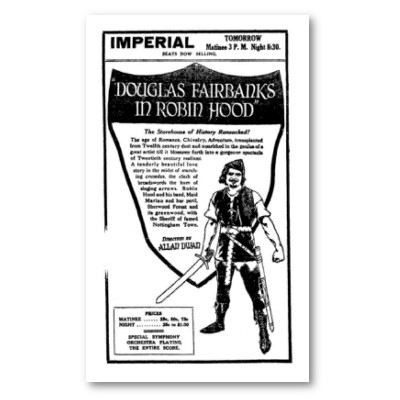

The title cards of silent films are fascinating for being overwrought—“All of England fell under the pall of John’s perfidy,” etc.—but one of the most startling in Douglas Fairbanks’ “Robin Hood” (1922) is rather straightforward:

From the mysterious depths of Sherwood Forest came whispers of the rise of a robber chief.

Why is this startling? Because it takes more than half the movie to appear.

Does any film genre age worse than action-adventure? You watch the quick-cut, world-traveling, big-explosion James Bond movies of today and then check out the first one, “Dr. No,” and it’s as if Bond has his feet propped up on a desk the entire movie. And that’s from 1962. Imagine an action-adventure movie 40 years before that. Before sound and color. When movies told us stories the way adults read to children: first the words (the title card), then the picture (two men dueling).

Does any film genre age worse than action-adventure? You watch the quick-cut, world-traveling, big-explosion James Bond movies of today and then check out the first one, “Dr. No,” and it’s as if Bond has his feet propped up on a desk the entire movie. And that’s from 1962. Imagine an action-adventure movie 40 years before that. Before sound and color. When movies told us stories the way adults read to children: first the words (the title card), then the picture (two men dueling).

At the time, Fairbanks’ “Robin Hood” was the most expensive movie ever made ($1.4 million), included the biggest set ever assembled (Richard’s castle), and was the first film to have its premiere at Grauman’s Chinese Theater. It also starred the biggest movie star of the era. Not only is the official title of the movie “Douglas Fairbanks in Robin Hood,” but when the man who will become Robin Hood is first introduced, the title card reminds us further who he is:

The Earl of Huntingdon,

Douglas Fairbanks

Most Robin Hood stories begin with Robin returning from the Crusades, but this one begins the day before he leaves. First there’s a jousting tournament: Huntingdon vs. Guy of Gibsourne (Paul Dickey). The latter cheats, loses, is bitter in defeat. Huntingdon, meanwhile, is wary of the prize: the veil of Maid Marian Fitzwalter (Enid Bennett). “Exempt me, sire,” Huntingdon declares, “I am afeared of women.” King Richard (Wallace Beery) laughs this off, Huntingdon receives his prize, then is chased by a multitude of women (like he’s a movie star), until he winds up in the moat.

Love between Robin and Marian blossoms that night. Initially Huntingdon is involved in rugged drinking and wrestling games with the men, and Richard objects:

Richard: Why hast thou no maid?

Huntingdon: When I return.

Richard: Nay, before you go, my good knight.

At that moment, as luck or chivalry would have it, Prince John (“sinister, dour, his heart inflamed with an unholy desire to succeed to Richard’s throne,” and played by Sam de Grasse) makes unwelcome moves toward Marian. Huntingdon intervenes. He wins the standoff but loses his heart to Marian. “I never knew a maid could—could be like you,” he says, holding both hands over his heart and descending to one knee. One wonders how long before that maneuver got corny.

The next morning, as the Christian soldiers move onward, Huntingdon leaves behind his squire, Little John (Alan Hale, who would play Little John twice more in the movies), whose job is to look after Marian. King Richard, less wise, leaves no one to look after Prince John, who, with the help of the High Sheriff of Nottingham (William Lowery), immediately sets about taxing and torturing. Marian, equally unwise, sends Little John off with news of Prince John’s perfidy, leaving herself unprotected. She winds up faking suicide to save her honor, while, in France, Huntingdon is suckered by Sir Guy, doubted by Richard, and he and Little John wind up in prison towers as the others head to Palestine. Little John subsequently frees them by bending prison bars with his bare hands; then they head back to England, where “sturdy men, rebellious to Prince John’s tyranny, sought refuge in Sherwood Forest... These lusty rebels only waited a leader to weld them into a band—an outlaw band destined to live immortal in legend and story.”

At this point, even for someone interested in cinematic history, the movie’s been a slog. I don’t know who needs Robin Hood more: the poor peasants of England or us. But then, an hour late, we get a fine introduction: 1) A boy brings coins and food to his starving parents; 2) the Sheriff of Nottingham is frozen in place by an arrow; 3) ditto “the Rich Man of Wakefield.” Finally Prince John orders a decree and a bag of gold to whomever can bring him this Robin Hood, but 4) an arrow pierces the throne and Robin Hood himself, in full gear, swoops down, takes the bag of gold, and leads the prince’s men on a merry chase through the castle. Fun!

When I first saw Douglas Fairbanks in a movie (“The Mark of Zorro” a few years ago), I was startled that he wasn’t Hollywood handsome—the way his son, Douglas Fairbanks, Jr., is Hollywood handsome. His face is somewhat fattish, without much of a jawline. But he is amazingly athletic and graceful. Even now, 88 years later, some of the stunts in “Robin Hood” are impressive, such as scaling down a castle corner by pressing himself against the adjoining walls. I wouldn’t be surprised if Jackie Chan got his falling-down-the-curtains stunt from Fairbanks, either.

Sherwood Forest looks cool, too, even by today’s standards. This was the age of the Hollywood extra, so dozens, maybe hundreds of Merry Men dot the landscape, while clumps of arrows stick out of nearly every tree. At one point one of the Merry Men shoots an arrow into a piece of wood tossed high into the air and dares Robin to match it; he does. He shoots two arrows into his piece of wood before it lands. That’s the great arrow stunt for this movie. No splitting arrows yet.

Sherwood Forest, back in the day of the cheap extra

The most aged aspect of the film, besides Huntingdon’s heart-holding, may be Robin’s “merriness.” He bounces. He prances. He skips like a little girl. It’s pretty funny to watch. Sometimes his merriness verges on the insane. He picks up a baby, who cries, and he laughs in its face. A reminder that recent portrayals of Robin Hood have toned down the one adjective associated with him. Wealth redistribution is serious business. Anyone anticipate Russell Crowe skipping?

Robin loses this merriness when he returns holy relics to the Priory of St. Catherine’s, where he discovers Marian alive. Alas, the Sheriff of Nottingham, listening outside the Priory’s walls, discovers this, too, then overhears a nun commenting on the mystery of the great outlaw. “Robin Hood to the poor, mayhap,” she says, “but he was born, Robert, Earl of Huntingdon.” This sets up our final act. Prince John seizes Marian while his men surround Sherwood. But the merry men—including a disguised King Richard—best the Prince’s men, while Robin takes the castle singlehandedly, kills Sir Guy, and holds off a dozen knights to protect Marian’s honor. For the sake of melodrama, he surrenders when he hears three blasts of a horn (signaling the three lions of King Richard), gives Marian a knife to kill herself if things get out of hand, and is tied to a stake before Prince John. He’s about to be diced by 40 arrows but Richard’s shield intervenes. The rest is mopping up. Prince John gets his comeuppance, but not in the bloody manner of today’s films. Instead Richard glowers at his brother, then picks him up and deposits him outside the castle. The drawbridge is raised and John looks around, scared. We can assume the rest: a slow death for a soft monarch or a quick death at the hands of an angry populace.

One tends to think of Robin Hood as a progressive (he robs from the rich and gives to the poor), but an argument can be made, particularly in this version, that he’s actually a religious conservative. A Richard loyalist, he fights for the Crusades and against excessive taxation. Only government men get robbed on camera. Meanwhile, both Robin and the film are devout. It begins where it begins because there’s no modern embarrassment yet over the Crusades. Far from it. “In far-off Palestine,” a title card reads halfway through, “Richard meets with victory and concludes a truce with the infidel,” after which we see Arabs marched through the streets while an English knight on horseback takes a laconic bite out of an apple. When conservative critics complain that modern Hollywood ignores traditional values, this is what they mean.

Showing good form and wearing a helluva long feather.

All previous entries

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)