Thursday April 27, 2017

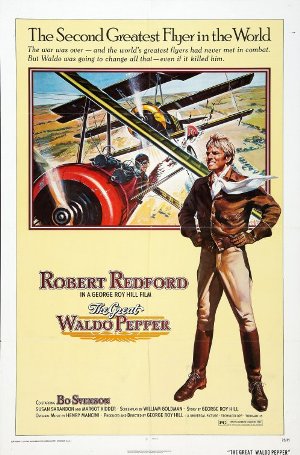

Movie Review: The Great Waldo Pepper (1974)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Patricia made a face the other night when I suggested watching Robert Redford in “The Great Waldo Pepper,” but it turned out she’d never seen it. I had. Three times? Five? More? Never in the theater, just on TV or cable, but probably not in 25 years. Most of the story was still in my head but I was curious how it had aged. Or how I had.

“Waldo” is lesser Redford from his glory period. He was the biggest movie star in the world, and from’73 to ’76 he starred in the following:

- “The Way We Were”

- “The Sting”

- “The Great Gatsby”

- “The Great Waldo Pepper”

- “Three Days of the Condor”

- “All the President’s Men”

Only “Gatsby” sucked. Redford was all wrong to play a man hopelessly in love; that’s not his character. He’s the one women are hopelessly in love with. Think Barbra in “The Way We Were,” Mary Tyler Moore weekly stuttering his name, and the prison guard’s wife in William Goldman’s book “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” who tells her husband she would gladly “get down on her hands and knees and crawl just for the chance to fuck him one time.” Again: She tells her husband this. So, yeah, not Gatsby.

Only “Gatsby” sucked. Redford was all wrong to play a man hopelessly in love; that’s not his character. He’s the one women are hopelessly in love with. Think Barbra in “The Way We Were,” Mary Tyler Moore weekly stuttering his name, and the prison guard’s wife in William Goldman’s book “Adventures in the Screen Trade,” who tells her husband she would gladly “get down on her hands and knees and crawl just for the chance to fuck him one time.” Again: She tells her husband this. So, yeah, not Gatsby.

Which raises a question: What was the essence of the Redford character during his heyday? Into his late ’30s, he was still playing the ingénue, still being shown the ropes by the like of Paul Newman and Jason Robards. And Barbra. His character has promise and his character often fails. That happened to be the essence of America at the time—how we viewed ourselves. “The Way We Were” actually makes the comparison explicit: “In a way he was like the country he lived in: everything came too easily to him.” And then it didn’t. That’s the point of the ’70s. When everything stopped being easy.

Pepper vs. Kessler

“Waldo Pepper” begins in the late 1920s, and while life isn’t exactly easy for the title character, it is freewheelin’. He’s a young blonde-haired hunk of man barnstorming around Nebraska, and selling simple folk on the thrills of aerial adventure. For some reason the movie posits him as a kind of charlatan, a bullshit artist. He’s supposed to come off a bit like Redford’s grifter in “The Sting,” but when you think about it he is actually selling something worthwhile: a chance to see the world from the sky. In the 1920s, that’s the stuff of gods.

The bullshit comes when he tells the local yokels about his dogfights during the Great War against German ace Ernst Kessler (cf., Ernest Udet): how he and four other guys had him in their sites but Kessler shot them all down, all except Pepper, whom he fought to a standstill until Pepper’s guns jammed. Kessler saw this, saw his opponent was helpless, but he didn’t take advantage. There was honor in the skies. He pulled up alongside him, saluted, and continued back to Germany. A great story. A true story. But not Pepper’s story. He didn’t make it into battle; he was still training recruits at the time. When he’s caught in the lie by his rival Axel Olsson (Bo Svenson, surprisingly good), his lament is: “It should’ve been me.”

That’s the tragedy of his life when we first meet him: He thinks he’s one of the best but never got the chance to prove it. The tragedy of the rest of the movie is that that life, the life we first see him living, disappears. He becomes increasingly saddled—first with a partner (Axel), then a flying circus (Doc Dihoefer’s), then federal regulations (former pal Newt, played by Geoffrey Lewis). But the real problem is other people’s ennui. Planes become everyday, so the crowds disappear, so the stunts have to become bigger and more dangerous to draw them back. The tension is between the crowds, who demand blood, and the feds, who demand safety, with our heroes caught in the middle.

The crowd gets what it wants. Axel’s movie-loving girlfriend, Mary Beth (Susan Sarandon), is pulled into wing-walking to add sex to the stunt; but despite her visions of grandeur, of becoming the “It Girl” of the skies, she freezes on the wing. Despite Herculean efforts to save her, she falls. (Patricia was legitimately, vocally shocked by this; she forgot what ’70s movies were like.) More gruesomely, Pepper’s pal, Ezra Stiles (Edward Hermann), finally finishes the plane that might be the first to perform an outside loop, but at this point, because of the Mary Beth tragedy, Waldo is grounded by the feds, so Ezra tries it himself. He’s not pilot enough to pull it off, and on the third try crashes. Trapped by the plane, the yokels gather around, some with cigarettes, and the leaking gas is ignited. Ezra is burned alive while everyone watches. This traumatized me as a kid, not least because I didn’t get it. Why did everyone just stand there? My father tried to explaining it to me, but, to be honest, as an adult now, 54, I think it’s part of the movie’s bullshit. It was the era’s extreme anti-populist message, and it feels false to me. And I’m a cynic.

Eventually, Waldo follows Axel to Hollywood, becomes a stunt man, then finally meets the great man, Ernst Kessler (Bo Brundin), on the set of a “Wings”-like aviation epic about Kessler’s dogfights. They talk, lament the passing of better days, then go off-script in the skies so they can dogfight without the guns in one final moment of freedom. They essentially kill themselves in the skies. It’s a dumb ending. It makes Thelma and Louise seem like they were really thinking it through.

A regular August Wilson

You know what I kept thinking watching this? Charles M. Schulz. He grew up in the Midwest (St. Paul, Minn.) in the 1920s. He could’ve been that kid getting gasoline for Waldo’s plane. He certainly bought into the romance of it all, then updated it in the 1960s with Snoopy and his Sopwith Camel, which is where I picked it up. Everything I learned about the Great War I learned from a beagle.

Was it Redford specifically, or the popular cinema at this time, that kept looking backwards, ceaselessly, toward the past? From ’73 to ’85, his only movies with contemporary settings were the two political thrillers above and “Electric Horseman” in 1979. Otherwise he’s a regular August Wilson:

- 1910s: “Out of Africa”

- 1920s: “The Great Gatsby”; “The Great Waldo Pepper”

- 1930s: “The Sting”; “The Natural”

- 1940s: “A Bridge Too Far”

- 1940s-50s: “The Way We Were”

- 1960s: “Brubaker”

A man out of time.

“Waldo” isn’t bad. Redford’s gorgeous, Bo Swenson is remarkably good, so is Sarandon. Writer-director George Roy Hill, a real aviation buff, gets the details right. It’s fun for an evening—Patricia liked it—but it doesn’t quite resonate. Like the bi-planes it’s filming, it just kind of drifts away.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)