Thursday September 12, 2019

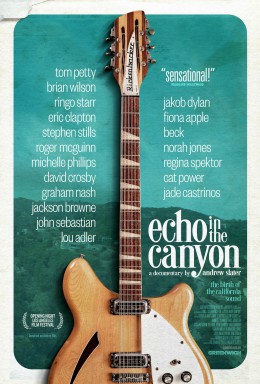

Movie Review: Echo in the Canyon (2018)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The most indelible recent cinematic moment involving Lauren Canyon music wasn’t from this doc about its heyday (1965-1967), but from a scene near the end of Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood,” when members of the Manson family pull into the long steep drive that leads to the rented home of Roman Polanski; and on the soundtrack, using irony like a scalpel, or maybe a bludgeon, QT plays The Mamas and the Papas’ 1967 hit single, “Twelve Thirty” with this exuberant line:

Young girls are coming to the can-yon!

It’s almost too on-the-nose. John Phillips’ song is about how great So Cal is, particularly compared to New York City, which is “dark and dirty,” and where things are so broken the clock outside always reads 12:30. Time has like stopped there, man, but Cali’s the future. You lift your blinds, say “Good morning” and really mean it.

It’s almost too on-the-nose. John Phillips’ song is about how great So Cal is, particularly compared to New York City, which is “dark and dirty,” and where things are so broken the clock outside always reads 12:30. Time has like stopped there, man, but Cali’s the future. You lift your blinds, say “Good morning” and really mean it.

Right. Until one early morning, on the other side of the window, therrrrrrre’s Charlie!

Good vibrations and our imaginations

I was looking forward to learning about the history of the Laurel Canyon music scene from this doc and almost groaned aloud (and probably did) when I realized it was more Jakob Dylan, looking like the haunted movie-star version of his dad, visiting and interviewing folks about those days and what they meant—interspersed with a 2015 homage concert put on by Dylan and contemporaries Fiona Apple, Beck, Nora Jones, Cat Power and Regina Spektor. This, meanwhile, is interspersed with archive footage of the bands in question (Byrds, Beach Boys, Buffalo Springfield), as well as scenes from the 1969 Jacques Demy film “Model Shop,” starring Gary Lockwood, which is set in the Canyon, and which supposedly gives us a feel for the times.

I would’ve preferred more archive footage and a talking head or two to sort the details. Give us the chronology. Tell us who besides David Crosby is full of shit.

They says the Beatles started it all, which makes sense since they started so much. They appeared on “Ed Sullivan” in February ’64, and Byrds frontman Roger McGuinn thought, “Hey, let’s do that.” He succeeded so well by doing Beatle-esque versions of folk songs that for a time, and without nearly the track record, the Byrds were called “the American Beatles.” Tough mantle.

Once it all began, everyone influenced everyone. This might be my favorite part of the doc: This song influenced that one which influenced the other. George Harrison even got a “If I Needed Someone” guitar riff from the Byrds’ cover of the Pete Seeger song “The Bells of Rhymney.” He even sent Derek Taylor to see McGuinn to see if it was OK. It was. Some cite this kind of collaboration and openness as the reason for the bursting creativity of those years.

But the doc is more laudatory than I would’ve liked; the filmmakers (Dylan, writer-director Andrew Slater) are too close to the story. We get some warts—Michelle Phillips slept around, David Crosby was a douche—but not a good discussion of why, beyond the track record (two No. 1s vs. 21), the Byrds weren’t the American Beatles. Here’s one answer: They were too earnest. The Beatles were sly and wicked, while Dylan, whom the Byrds relied on for material, had almost a third eye he was so timeless. There aren’t many geniuses in rock ‘n’ roll but those were two. The doc needed to get into the why of it while still celebrating it.

Can’t go on indefinitely

I liked hearing Jakob and the others singing but I was less impressed with him as an interviewer. His main technique is to say nothing. Most of the time, it’s not a bad technique—cf., Robert Caro—but it’s not exactly cinematic. Plus a good interviewer needs follow-ups and, I don’t know, curiosity. People talk up the flak McGuinn encountered when he mixed rock and folk, and no one references Newport? Not even a “I guess your dad knew something about that”? And doesn’t the doc imply Dylan got the idea from McGuinn rather than hearing the wails of Eric Burden and the Animals on “House of the Rising Sun” coming over his car radio? Or is the latter story apocryphal? If so, this was a chance to clear that up. They didn't. They muddied the waters.

How did everybody meet? I kept expecting to hear “Creeque Alley,” which is really the origin story of so many of these bands and personalities, but it never comes. I wanted more on the breakups, too. They harmonized beautifully on a west-coast idealism but couldn’t keep the harmony going. I wanted that dynamic: the disharmony among those beautiful harmonies, with Charlie waiting in the wings. What wasa he, after all, but another So Cal resident influenced by the Beatles.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)