Tuesday January 08, 2013

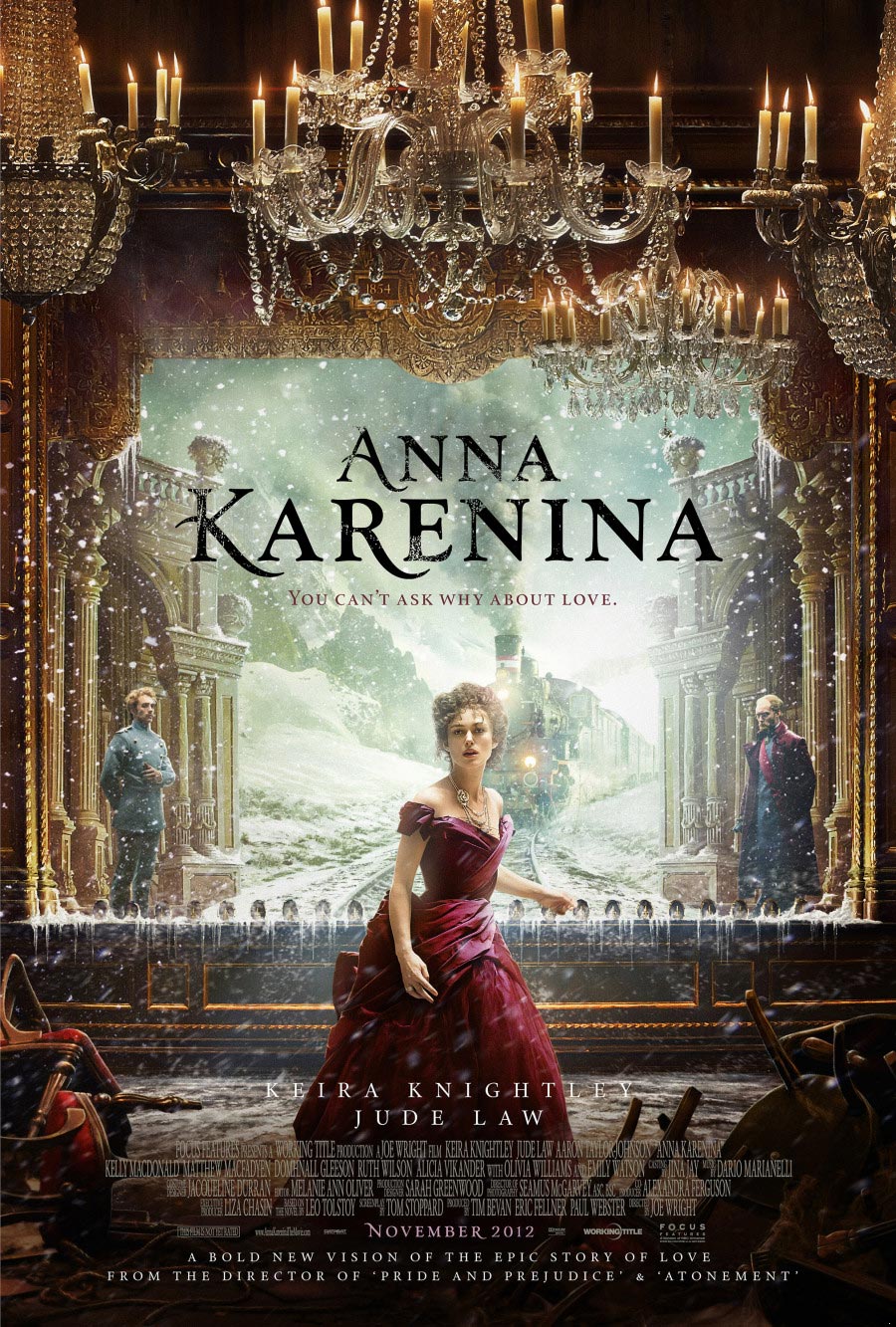

Movie Review: Anna Karenina (2012)

WARNING: SPOILERS

I was worried I’d be bored with it since I already knew the story: Russia, married woman, affair, train. But I became intrigued by the purposeful staginess and theatricality from director Joe Wright. Or was that in the screenplay by Tom Stoppard? That’s a Stoppard staple.

It begins in a theater, on stage, with the words “Anna Karenina” on the curtain. I expected such theatricality to fall away, as it tends to in movies, and it does, at times, and we’re “in the scene” rather than “in the scene of the scene.” But it takes awhile to do this and the theatricality almost always returns—sometimes at  unexpected moments, such as at the end when Anna (Keira Knightley) is trapped by love and jealousy and society and doesn’t know which way to turn until she sees a way out. It was unexpected at this point in the story because I’d already equated this theatricality with the airs, theatricality and stagecraft in 19th-century Russian high society, of which Anna, here, was no longer a part. So why remind us? Someone with more time on their hands can go scene-by-scene and suggest why this scene dropped the cinematic illusion and that scene maintained the illusion. I’m sure Wright and Stoppard had their reasons.

unexpected moments, such as at the end when Anna (Keira Knightley) is trapped by love and jealousy and society and doesn’t know which way to turn until she sees a way out. It was unexpected at this point in the story because I’d already equated this theatricality with the airs, theatricality and stagecraft in 19th-century Russian high society, of which Anna, here, was no longer a part. So why remind us? Someone with more time on their hands can go scene-by-scene and suggest why this scene dropped the cinematic illusion and that scene maintained the illusion. I’m sure Wright and Stoppard had their reasons.

I got tired of the contrivance, to be honest. I’ve never been a fan of it. I suppose I think it’s the job of the storyteller to put me in the story and it’s my job, as listener or viewer, to take myself out of it. There’s a tyranny and pomposity to this kind of post-modernism as well as pointlessness. It’s weak tyranny. I will tell you when and where you will be taken out of the story, thereby weakening the story. I search for engagement with the story rather than removal from it. I object to the author’s strong hand on the back of my neck.

That said, there were times when the contrivance worked. I’m thinking of the moment Vronsky’s horse falls off the stage during the race—that was powerful—or when Levin (Domhnall Gleeson) gives up Moscow society for his country estate and leaves the suffocating artifice of the stage for the cold, harsh reality of the Russian winter. He turns, steps outside, and it’s as if we can breathe again. It’s as if we didn’t realize how much we were suffocating until that moment.

My Anna

It’s been decades since I’ve read “Anna Karenina”—final quarter of college, spring 1987—and I’d forgotten a lot of it. Levin, for example. Completely. Even though he’s half the story. He was my guy back then—in love, searching for meaning—but I found him harder to take here. I’m older now, and harsher. I watched his dull, youthful stabs at love and rolled my eyes. I almost felt like Levin’s Marxist brother, Nikolai (David Wilmot), who, dying, rails against the privileged classes, saying, “Romantic love will be the last illusion of the old order.” In 1987, that line would have pained me, as it no doubt pains Levin. Now I just shrug: “Maybe.” But I lack Nikolai’s conviction for what comes after. I saw the mess Nikolai’s brethren made of it.

At the same time, I was charmed by the flirtation, and the held-breath, of the game of blocks Levin has with his unrequited love, Kitty (the Swedish actress Alicia Vikander, with whom I was also charmed), later in the movie. By this point he’s suffered, she’s suffered (she loved Vronsky), and they’ve both matured. He’s in her parlor, visiting, and there are blocks there, and they play a game, almost like “Wheel of Fortune,” in which one side asks a question or makes a statement using only the first letter of each word, and the other side tries to guess what it is. In this way, this safe way, they reveal their feelings. DNMN, for example, from Levin, means, “Did No Mean Never?” referring to his earlier marriage proposal. TIDNK, she says, meaning “Then I Did Not Know.” And now? he asks. She asks, via the blocks, for his forgiveness for the way she was. He responds with these letters: ILY. No translation needed. That’s a sweet moment, and recalls the various wordgames from Stoppard’s “Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead.”

In Tolstoy’s novel, I remember having more sympathy for Anna and less for Karenin, who seemed a prig to me. But as the movie progressed, I found myself less and less sympathetic with Anna, who gives up her child, etc., for her one great love, Vronsky (Aaron Taylor-Johnson). Except Vronsky is, for the most part, shallow and callow. It’s a game to him, until it’s not, and Anna seems a fool for falling in love with him as completely as she does. Meanwhile, her husband, Karenin (Jude Law), publicly cuckolded, seems a decent, moral man who mostly tries to do the right thing.

Kundera's Anna

Our sympathies in this story are no small matter. Milan Kundera, in the last pages of his book of essays, “The Art of the Novel,” writes the following:

When Tolstoy sketched the first draft of Anna Karenina, Anna was a most unsympathetic woman, and her tragic end was entirely deserved and justified. The final version of the novel is very different, but I do not believe that Tolstoy had revised his moral ideas in the meantime; I would say, rather, that in the course of writing, he was listening to another voice than that of his personal moral conviction. He was listening to what I would like to call the wisdom of the novel. Every true novelist listens for that suprapersonal wisdom, which explains why great novels are always a little more intelligent than their authors. Novelists who are more intelligent than their books should go into another line of work.

But what is that wisdom, what is the novel? There is a fine Jewish proverb: Man thinks, God laughs. … Because man thinks and the truth escapes him. Because the more men think, the more one man's thought diverges from another's. And finally, because man is never what he thinks he is.

Maybe the movie needed more drafts. By the end, Anna, never particularly likeable, is insufferable. She’s mad with love, mad with jealousy, mad with loneliness. She thinks she can go out into high society again, and pretends it doesn’t matter what people think. It’s a shock when it does. By this point, I began to feel sorry for, all of people, Vronsky, who has to put up with her histrionics. Finally she sees her way out. She met Count Vronsky on a train and ends her life beneath one. It’s this story in a newspaper account of the time—woman throws herself beneath train—that led Tolstoy to write “Anna Karenina” in the first place.

“Anna Karenina” looks beautiful, is filmed gorgeously, and I loved Matthew Macfadyen as Oblonsky. But the story’s dilemma is truly the dilemma of another time and place. Attempts to bring the story to our time should bring some of its wisdom with it.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)