Movie Reviews - 2013 posts

Monday December 16, 2013

Movie Review: Inside Llewyn Davis (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It’s the ending.

I’d heard it was the way the Coens treated him. They were like Old Testament gods toying with their creation again, making sure nothing went his way again, and people were, I heard, objecting. But that’s not the problem with “Inside Llewyn Davis.” The problem is the ending. It just ends. Au revoir.

It ends where it begins, but is it ending where it began—i.e., with the same scene— or is it merely similar to the opening scene, as waking up at the Gorfeins’ place at the end (purring kitty, sticking head sideways out doorway) is similar to waking up in the beginning? It’s part of the nightmarish cyclical nature of the life of Llewyn Davis (Oscar Isaac), and of all of our lives, really. He and we are trapped in it and we’re not allowed out. Except one way.

We get Bob more prominent in the end, a young Bob Dylan coming onto the Gaslight Cafe stage with a bit of a song that sounds like Llewyn’s, or like traditional folk songs anyway (the whole “fare the well” thing), which is the final nail in the coffin for this Dave Van Ronk-alike. The Coens own up to that, by the way: the Van Ronk comparison. Even the album names and covers match. But it stops there. Van Ronk ruled. He was the Mayor of MacDougal Street, and beloved. Llewyn is compressed, bitter, and so very very tired. He is the talent doomed to never be known. He is the modern ...

Let me back up for a second.

500 Miles

There are some great line readings in the movie, particularly from Carey Mulligan as Jean, part of the folksinging husband/wife duo Jim and Jean (Jim = Justin Timberlake),  but my favorite may be from F. Murray Abraham, who plays Bud Grossman, AKA Albert Grossman, the man who managed Bob Dylan, and who created Peter, Paul and Mary. The great odyssey in the movie, the attempt to get out, and up, rather than out and down, which is what Llewyn’s former singing partner does (off the George Washington Bridge), is Llewyn’s trip to Chicago to play for Bud at the Gate of Horn. It’s nightmarish getting there, sometimes even hellish, but he does it. And there’s this devilish figure waiting for him at the end.

but my favorite may be from F. Murray Abraham, who plays Bud Grossman, AKA Albert Grossman, the man who managed Bob Dylan, and who created Peter, Paul and Mary. The great odyssey in the movie, the attempt to get out, and up, rather than out and down, which is what Llewyn’s former singing partner does (off the George Washington Bridge), is Llewyn’s trip to Chicago to play for Bud at the Gate of Horn. It’s nightmarish getting there, sometimes even hellish, but he does it. And there’s this devilish figure waiting for him at the end.

Llewyn has a copy of his album with him, “Inside Llewyn Davis,” but Bud, rather than listen to the record, wants to hear him live. “You’re here, play me something.” Pause. “Play me something from inside Llewyn Davis.” That’s it. It’s perfect. It has just the right soupçon of condescension about Llewyn’s album title and maybe his talent. F. Murray is so good in such a small part, and you’re so grateful to be seeing him onscreen again, that you might not make the connection immediately. I didn’t. It wasn’t until we were walking back to the car, Patricia and I, talking over the movie, and I was thinking that Llewyn Davis was the talent destined to be unknown, the talent usurped by the greater talent, Bob Dylan, making him ... of course! ... the modern Salieri, the man usurped by Mozart in “Amadeus,” and who was played by, of course, F. Murray Abraham.

Of course Llewyn isn’t even Salieri. Salieri was hugely successful in his time, beloved by kings, but he also recognized the greater talent in Mozart. Llewyn gets nowhere. And does he even recognize the greater talent in Dylan? We don’t know. He listens for a few seconds and then leaves to get beat up in the alleyway for past crimes.

At the Gate of Horn audition, Llewyn plays a beautiful ballad, “The Death of Queen Jane,” and plays it well, and there’s a pause. Then Grossman says, “I don’t see a lot of money here.” Then he talks up Troy Nelson (Stark Sands), the too-innocent, cereal-slurping, folk-singing soldier stationed at Fort Dix, who, Grossman says, “connects with people.” Meaning Llewyn doesn’t. But Grossman gives him a way out. How is he with harmonies? Does he want to be part of a group he’s putting together? This will be Peter, Paul and Mary, one assumes, and Llewyn could’ve been Paul in that configuration, but he says no. He’s a solo act. It’s his way or the highway so it’s the highway. CUT TO: Llewyn struggling comically forward in the snow against the bitter Chicago wind.

Maybe that should’ve been the end: rejected by Salieri. But the Coens needed Llewyn to return to New York and get trapped in the bottle again.

Please Mssrs. Coens

I’ll say this: Not many filmmakers do place better than the Coens, whether it’s Florida in the 1930s, Minneapolis in 1967, or Greenwich Village in 1961. The streets Llewyn walks down all seem like the street Dylan walks down with Suze Rotolo on the cover of “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan.”

They get all the little details right: the caricatures of Llewyn’s agent, Mel Novikoff (Jerry Grayson), that he has framed on his walls, along with the framed copy of SING OUT! magazine, the folk music staple. Even the Gorfeins (Ethan Phillips, Robin Bartlett), the ultra-liberal, upper west side couple who let Llewyn stay there, are perfect. Their guests, too, Marty Green and Janet Fung, who rename themselves the Greenfungs, not to mention the humorless bearded music historian Joe Flom (Bradley Mott). I’m curious, though, why the Coens named him thus, after the famous M&A attorney. And why name Llewyn’s former singing partner, the one who jumped off the George Washington Bridge, Mike Timlin? What is it with the Coens using other people’s names? We got Ron Meshbesher in “A Serious Man” and Al Milgrom here. Is it homage? Do they like funny sounding names?

Should we worry about the Old Testament quality to the Coens? They tend to punish all of their creations (it’s called a story) but a few are allowed happy endings: Herbert and Ed McDunnough, Jeff Lebowski, Ulysses Everett McGill. Most are not: Barton Fink, Larry Gopnik, Llewyn Davis. What do these last have in common? Too much pride and prickliness. And Jewishness. The Coens are like Bernard Malamud this way: tougher on their own.

One of the oddities of the trailer is that everyone rails against Llewyn, particularly Jean, calling him an asshole (in another great line reading), but he never does anything really assholish in the trailer; he’s simply put-upon. But in the movie he is an asshole: he sleeps with Jean, explodes at the Gorfeins, gets drunk and yells obscenities at a kindly old woman playing a harp at the Gaslight because he’s mad at someone else. He’s got that prickly, prideful solitariness.

Does his need to be alone relate to the death of his former partner? The Timlin tragedy just hangs in the background. It’s a dull ache in Llewyn’s side that never goes away but is never explained. Same with the 2-year-old in Akron. Same with Jean. Most of Llewyn’s crimes are in the past. When we catch up with him he’s about to be punished.

Hang me, oh hang me

“Llewyn Davis” is also a movie about music, and the music, produced by T. Bone Burnett, is exceptional. The Coens give us entire songs. They hold on the performer, singing, and Oscar Isaac can sing.

“Hang Me, Oh Hang Me,” Llewyn sings in the beginning, and for the rest of the movie the Coens come close to doing it. Do Llewyn’s travails make him a better performer? That would be the easy way out of the story. That’s what most Hollywood movies would do. Llewyn is on this odyssey, often with Ulysses the cat, and he comes back a wiser man, and that wisdom leads to success. That’s the lie Hollywood often tells us, because it’s the lie we often tell ourselves, because otherwise why all this? Why travails, and pain, and sorrow, if it doesn’t lead to something? But here Llewyn’s travails lead to Dylan’s success.

I think I’ve actually written myself into liking “Inside Llewyn Davis." I want to see it again. The Coens often do this to me. The movie feels like an answer, and I’m just missing the answer, and maybe if I see it again I’ll find it. But I know I won’t. The Coens are masters at giving us the answer of the non-answer. This is another one.

Au revoir.

Sunday December 15, 2013

Movie Review: Spring Breakers (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It takes a particular kind of talent to make tits and ass this boring, but apparently writer-director Harmony Korine, who gave us the powerful “Kids” in 1995, is that kind of talent.

“Spring Breakers” is an arthouse version of an exploitation flick. That almost makes it sound interesting but “Spring Breakers” is not. It’s dull, atmospheric, repetitive. It’s about four college girls—three rowdy blondes and one Christian brunette, Faith (Selena Gomez)—who do what they can to go from wherever they are to St. Petersburg, Fla., for spring break. In a way it’s about the bastard children of Britney Spears and George W. Bush, the ones who grew up watching her videos and hearing snippets of his speeches, and drew all the appropriate lessons about looks and smarts.

It’s our past come back to haunt us, y’all.

The unreal real thing

What do the girls do in St. Pete? Ride scooters, go to the beach, party hardy. There’s beer bongs and dancing and not much dialogue.  It’s hypnotic and dreamlike. They need this, these girls. They need to get away. From studying. About history and shit. An early good scene shows two of them, Candy and Brit (Vanessa Hudgens and Ashley Benson), as the professor goes on about ... is it the civil rights movement? The girls stop listening to draw a dick on their notebooks and take turns mock licking it. Then they put on ski masks and rob a diner to come up with the scratch for the trip.

It’s hypnotic and dreamlike. They need this, these girls. They need to get away. From studying. About history and shit. An early good scene shows two of them, Candy and Brit (Vanessa Hudgens and Ashley Benson), as the professor goes on about ... is it the civil rights movement? The girls stop listening to draw a dick on their notebooks and take turns mock licking it. Then they put on ski masks and rob a diner to come up with the scratch for the trip.

For some reason, amid all the partying in St. Pete, they get singled out for arrest—or maybe they’re just part of the long line of kids busted that evening—but either way they wind up before the judge and then in jail and then bailed out of jail by Alien (James Franco), a local rapper and wannabe gangster. And at this point we think this: comeuppance. We think: These college girls tried to be what they weren’t—tough and bad ass—and now they’re dealing with the real thing; and now they’re going to pay. That’s the direction we seem to be going in. When Alien tries to seduce Faith, leaning in close, insinuating, it’s super creepy, and she begs the others to leave with her. They don’t. So she gets on the bus alone and gets out of Dodge. Why don’t they? Because they like it. Because they’re the real thing. At least two of them.

A key scene (although there really aren’t many scenes) is when these two, Candy and Brit, tell Alien how they robbed the diner, and how they yelled at everyone to get on the fucking floor, and they do this with Alien. They use his guns to tell him to get on the fucking floor. They put the gun in his mouth. They make him suck it. It’s sexy, actually, our first sexy scene in the movie, and it reverses the power structure within the movie. Suddenly they seem like the real deal and he seems the fake: the sad white boy with cornrows and gold-capped teeth who buys into gangsta culture.

Alien is in the midst of a turf war with a childhood friend and mentor, Archie (Gucci Mane), and they exchange words, and off of one bridge, gunfire. Cotty (Rachel Korine), the third rowdy blonde, gets hit, and scared, and goes back home, wherever that is. That leaves two. And Alien, who used to have a bit of a posse, at least the creepy ATL Twins (Sidney and Thurman Sewell), attacks Archie’s well-guarded compound with only himself and the two girls wearing pink ski masks. It’s all hallucinatory and in slow-mo, and Alien, that faker, never makes it off the dock. He’s killed fast. The two girls? They take out everyone else, including Archie, without a scratch, without splattered blood. Apparently Archie's a faker, too. No one's the real thing here. Then they ride out of Dodge in Alien’s Ferrari and into the sunset.

The unhappy happy ending

Is it a happy ending? Maybe it’s a play on a happy ending. It’s a fake, wish-fulfillment ending with a fake, arthouse tone. It’s the worst of both worlds.

I know others disagree. “Spring Breakers” is making a lot of 10-best lists. Certain critics see something profound in its awfulness: in the way it subverts the male gaze, or in its implied condemnation of the vapidity of our culture. I just hated it. How do you make a movie about the utter vapidity of our culture without being vapid? This was Harmony Korine’s attempt. Next.

Friday December 13, 2013

Movie Review: Nebraska (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

In “Nebraska,” David Grant (Will Forte), a middle-aged man with a crappy retail-sales job and a nowhere life, offers to drive his grizzled, alcoholic father, Woody (Bruce Dern), who believes himself to be a million-dollar sweepstakes winner, the 900 miles or so from Billings, Mont., where they live, to Lincoln, Neb., the headquarters of the publishing house offering the prize. Along the way, circumstances compel them to stop in Hawthorne, Neb., where Woody grew up, for a visit with aunts, uncles, cousins, friends. These people are generally reticent, dull, and, once Woody’s suspect bounty is revealed, greedy. They are also without hope and opportunity, living in a dead-end town in a dead-end part of the country during the dead-end of the global financial meltdown. It’s a comedy.

What to make of “Nebraska”? It’s beautifully photographed (black and white), and doesn’t feel false,necessarily,  since we all have distant relatives that seem dull and dimwitted. But there’s usually more to them, isn’t there? Even if the more is less? Hardly a racist word is spoken here, for example. Just something about “Jap cars” and even that racism seems old. It’s circa 1991. Or 1941.

since we all have distant relatives that seem dull and dimwitted. But there’s usually more to them, isn’t there? Even if the more is less? Hardly a racist word is spoken here, for example. Just something about “Jap cars” and even that racism seems old. It’s circa 1991. Or 1941.

No, the Grants’ distant relatives are just comic relief. They add to the sad absurdity that is Woody’s quest. The women gather in the kitchen to gossip and the men gather in the living room to watch television in silence. If they’re old, they fall asleep on the couch. If they’re young, they drink beer on the porch. David has two cousins like that, Bart and Cole (Tim Driscoll and Devin Ratray), who stare at him with bug eyes, belittle his driving abilities (and, implied, manhood), and late in the game actually rob Woody of his sweepstakes announcement. They seem like characters John Candy could have played on SCTV.

At the same time, I was rarely uninterested in “Nebraska.” It affected me. Its tone sank into my bones like gray weather.

Problems with the basic premise

The opening image is a static shot of a nondescript part of Billings. In the distance, an old, grizzled man (Woody) walks towards us on the thin strip of grass between an unmoving railroad and a constantly moving highway: between the static past, you could say, and the constantly moving present. A cop stops him and asks, over the roar of the traffic, where he’s headed. Woody points toward us. And where is he coming from? Woody points back. Cue credits. At this point, I was ready to love the movie.

But I had trouble getting beyond its premise. Why would David agree to take his father to Lincoln to collect nothing? Isn’t his father suffering the early stages of Alzheimer’s? And isn’t David’s own life going nowhere? He’s a clerk at an electronics store, lives in a flimsy apartment, wishes to start up a relationship again with a woman he doesn’t love. His life is sad sad sad. Does he have ambitions? Hopes? Fears? Who is he?

Later, David talks about his reasons for the trip: 1) He wants to get out of Billings; 2) he wants to spend more time with the old man; and 3) he wants the old man to shut up about the million dollars. Reasons 1 and 3 I can see, but 2? Who wants to spend days in a car with Bruce Dern?

I know, cheap shot, but this may be an instance where good casting works against a movie. Dern is getting acclaim for the role—best actor at Cannes, etc.—and he’s good, but a premise of the movie, a third-act revelation, is that David is “just like his father.” Really? David is too kind and too passive. He goes along to get along. So we’re supposed to believe that this cantankerous, alcoholic old man, played by Bruce Dern of all actors, was kind and passive in his youth? Have the filmmakers seen “Coming Home”? “The Great Gatsby”? “Marnie”? Anything?

For the impromptu family reunion in Hawthorne, both David’s mother, Kate (June Squib), and his more successful brother, Ross (Bob Odenkirk), join them. I like how both sons are played by comedians. I like how Ross is more successful but not a jerk. I didn’t like the mother’s outlandishness. Too much. When she hiked up her skirt at the cemetery to show a former beau what he was missing? Like that.

By this point Woody has blabbed about his winnings and everyone’s believed him, and when the family says, “No, he didn’t really win a million dollars,” everyone thinks it’s an attempt to shake them off the scent. Folks begin behaving badly. So do the Grants. Some of it’s funny. Mostly it’s just sad.

And all the while we’re wondering this: How can the filmmakers—director Alexander Payne (“The Descendants”) and first-time screenwriter Bob Nelson—give us a satisfying end? What can this road trip bring but more disappointment?

Here’s how. They make David even kinder than we thought he was, with access to more money than we thought he had.

Prize winner

In Lincoln, David and Woody walk into the home office of the publishing house, a nondescript building in a nondescript part of town, and a nondescript woman greets them. They say why they’ve come, she takes Woody’s announcement and punches the numbers into her computer. Sorry, she says. You didn’t win. Then she offers a consolation: How about a cap or blanket? He chooses the cap. He puts it on. It reads: PRIZE WINNER.

Why did he want the million dollars? That’s a question that’s come up several times in the movie, absurdly to me, since who wouldn’t want a million dollars? Money means opportunity and options. It means the end to the dead-end. But it’s asked, and Woody replies that he always wanted a brand-new truck (even though his driver’s license has been taken away), and an air compressor (even though he no longer has use for one). He also wishes he had a little something to leave his sons. He doesn’t like the idea of leaving them nothing.

“You should’ve thought of that before you threw your life away,” David replies.

Kidding. David doesn’t say that. Instead, in a used-car lot in Lincoln, he trades in his Japanese car for an American truck. Then he buys his father a useless brand-new air compressor. Then they return to Hawthorne and David lets Woody drive the truck slowly down Main Street.

It’s a sweet moment, a not-bad resolution. At the same time, it requires us to believe that everyone that matters to Woody in Hawthorne, former loves and current enemies, would be in the proper place at the proper time to see his one-man victory parade. It also requires us to believe that David has more disposable income than we were led to believe.

But that’s our end. And off they ride, a debt-ridden father and son, into a black-and-white American sunset.

I wanted to like “Nebraska.” But it portrays us as both better (David) and worse (almost everyone else) than we really are.

Wednesday December 11, 2013

Movie Review: American Hustle (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

David O. Russell’s “American Hustle” is a movie that earns the “American” in its title. It’s big, brassy, energetic, corrupt, and has great cleavage. It’s fascinating and fun. It’s a movie that never sits still. It’s about all the little scams everyone plays every day along with the big scams they get caught up in. It’s about how no one’s clean but some people are smart. At one point, maybe two-thirds of the way through, I thought, “After all these years of making movies for us, how nice that someone finally made a movie for Martin Scorsese.”

“American Hustle” is also a movie that earns the “Hustle” in its title, since it’s about people hustling/striving to get ahead and people just hustling/conning everyone else. Usually the two go together.

If you can't tell, I loved the hell out of this movie.

You ready?

1979 is getting its closeup

It’s the 1970s. Irving Rosenfeld (Christian Bale), fat, from the Bronx, and with the worst combover in the world, is involved in his little scams in and around Long Island and New Jersey—shady loans, counterfeit art, plus a few legitimate dry cleaning stores—when he meets Sydney Prosser (Amy Adams) at a party.  Boom. She’s from New Mexico, works at Cosmopolitan magazine, but jumps into his scams with both feet. Puts on a British accent and displays leg and that great braless cleavage of the era as they schnooker anyone they can find. Then they schnooker the wrong guy, Richie DiMaso (Bradley Cooper), a low-level field agent for the FBI. Since only Sydney puts her hands on the money, only she goes to jail. Freaks her out. Richie uses this, not to mention Irving’s love for her, as leverage to get both of them to help with an operation involving Carmine Polito (Jeremy Renner), the popular, populist mayor of Camden, N.J.

Boom. She’s from New Mexico, works at Cosmopolitan magazine, but jumps into his scams with both feet. Puts on a British accent and displays leg and that great braless cleavage of the era as they schnooker anyone they can find. Then they schnooker the wrong guy, Richie DiMaso (Bradley Cooper), a low-level field agent for the FBI. Since only Sydney puts her hands on the money, only she goes to jail. Freaks her out. Richie uses this, not to mention Irving’s love for her, as leverage to get both of them to help with an operation involving Carmine Polito (Jeremy Renner), the popular, populist mayor of Camden, N.J.

Polito, the father in New Jersey’s version of “The Brady Bunch,” including a black kid he adopted, has helped make gambling legal in the state, and he wants to help reopen Atlantic City, too. So the FBI creates an Arab buyer who will bankroll refurbishing the run-down seaside town for a little something under-the-table. I supposed I should’ve known going in that this was about Abscam. The Iran hostage crisis last year and Abscam this year. 1979 is finally gets its closeup.

What was the deal with Abscam again? Wasn’t it viewed as entrapment? It wanted to be Watergate. It wanted to prove big-time corruption but proved—just barely—small-time corruptibility. Which is like proving nothing at all.

The operation is mostly internecine battles: between Richie, who wants to make it as big as possible, and Irving, who wants to keep the operation small and controlled; between Richie and his immediate superior, Stoddard Thorsen (a hilarious Louis C.K.), a careful stump of a bureaucrat, who refuses to OK any of Richie’s extravagant operational needs (an airplane, a hotel suite, $2 million in wire transfers) without a push from his boss, Anthony Amado (Alessandro Nivola, channeling in looks a young Harvey Keitel, and in voice a young Christopher Walken), who has Richie’s lust for fame. It’s also a battle for Sydney, between Richie and Irving, but who she’s scamming, if she is scamming anyone, we don’t know. She might not know.

The greater battle is probably internal. Irving is being forced to help someone he doesn’t like (Richie) to ruin the life of someone he does (Carmine). He’s doing it for Sydney but in the process he’s losing Sydney. Plus his crazy wife, Rosalyn (Jennifer Lawrence), threatens to ruin the whole operation. Plus the thing he wants small and controlled keeps getting bigger and crazier.

The movie reached a crescendo for me—a testament to the outsized craziness of American life and storytelling—in Atlantic City, when the mob shows up, smiling and hanging at the bar up front, and being whisked in for high-powered meetings in the back room. The face at the bar belongs to Pete Musane (Jack Huston, “Boardwalk Empire”), polite, mustachioed, making eyes at Rosalyn. The face in the back room, and it’s a shock, a wonderful shock, belongs to Victor Tellegio, an uncredited Robert De Niro, doing some of his best acting in years. He suggests speeding up citizenship papers for Sheik Abdullah (Michael Pena), and Carmine, somewhat uncomfortable, agrees to set up meetings with U.S. representatives and senators he knows. The helpless look in Irving’s eyes at all of these moving piece is beautifully contrasted with the greedy gleam in Richie’s. Richie sees greatness coming out of this; Irving merely sees his own death. You can scam the mayor of Camden, N.J., but you can’t scam the mob. The FBI maybe but not him. With every step, it seems, he has more to lose: first Sydney, then Rosalyn, then his life.

How he gets out of it, and the comeuppance of Richie, is a joy to watch. Early on, Irving says this: “As far as I see, people are always conning each other to get what they want.” Irving began the movie conning others, then Richie conned him, and together they began conning Carmine. But the con got too big. So Irving scales it back by conning Richie again.

God, it’s fun.

The first and final con

I flashed on a few other movies watching this one: “Goodfellas” for its energy and narration and camera movement and made guys; “Atlantic City” for the attempt to resurrect the boardwalk; “Argo,” for the era, and for this thought: Can the Academy award its best picture to back-to-back 1979 movies? Probably not. Shame. This one deserves it more.

You’ll hear a lot about the acting, but it’s not in the weight Bale gained nor in his elaborate combover nor in Bradley Cooper’s perm—all of which are fun. It’s in the eyes. The con, and then the concern, in Irving’s, the need in Richie’s, and the fear, the dizzying fear, in Sydney’s. It’s the death stare of Victor Tellegio, delivered as only De Niro can deliver it. It’s in the officious blankness in Stoddard Thorsen’s eyes. A small favorite moment: After all that Richie puts him through, there’s no vindictiveness in Stoddard’s eyes in the end. His eyes remain blank and officious. Like he’s simply wondering when he can go home.

Are there mistakes? Sure. Is Carmine too decent? We don’t really get why Richie targets him in the first place. We barely understand his crime. To him, the graft seems a necessary byproduct of what he really wants to do, which is creating working class jobs for the people of New Jersey. And in the backroom staredown between Victor, who, oops, knows Arabic, and the fake Sheik, who doesn’t, well, isn’t the jig up right there? Yet it isn’t. Plus how does Pena’s FBI agent suddenly know entire sentences in Arabic? Has he been studying?

No matter. Go. Most movies of this type begin with the disclaimer “Based on a true story,” but “American Hustle”’s disclaimer is a little looser, a little more American. It says: “Some of this actually happened.” Meaning most of it didn’t. The movie’s our first and final con. A joyful one.

Tuesday December 10, 2013

Movie Review: Philomena (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

The power of Stephen Frear’s “Philomena” lies in the performance and in the message.

A simple woman searches for her long-lost son with the help of an erudite former BBC reporter. Early on, you think the movie is merely an odd-couple road-trip—him, with all his Oxford smarts, learning her simple wisdom—and that’s certainly part of it. You also think the movie is about the journey (them together) more than the destination (what happened to her son), but halfway through we wind up at that destination, and it dead-ends, and we wonder where the story can possibly go. Is there a path? There is. Through there. Then another dead-end and another path. And we keep squeezing through onto these smaller paths, wondering if we’re going to make it out, until suddenly everything opens up into a field, and we stand there for a second, happy, even as we recognize we’ve been there before. It’s Roscrea, the convent in Ireland where we started. At this point the former BBC reporter, Martin Sixsmith (Steve Coogan), recites the following stanza to the woman, Philomena Lee (Judi Dench):

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

She’s effusive, and asks if he came up with it just then.

Martin (slightly embarrassed): It’s T.S. Eliot.

Philomena (unembarrassed): Oh. Well, it’s still very nice.

It’s the “still” that gets me. It’s the way Dench says it. It’s the way Dench says everything. She reminds me of my mother and Sixsmith reminds me of me. I don’t see me in many movies, and I see my mother less often, so it’s nice to see us up there for a change.

The greater sin

In 1951 Philomena Lee (Sophie Kennedy Clark) met a young boy at a carnival, and after a candied apple knew sin.  Her family, ashamed of the out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sends her to Roscrea, where the nuns grill her. “Did you take your knickers down?” they ask. “Did you enjoy your sin?” She signs a document giving the convent the right to put her child up for adoption; then she and other unwed mothers work off what they owe in the laundry room. They’re allowed an hour a day with their child. Philomena’s is named Anthony. At age 3 he’s taken away. She hasn’t seen him since.

Her family, ashamed of the out-of-wedlock pregnancy, sends her to Roscrea, where the nuns grill her. “Did you take your knickers down?” they ask. “Did you enjoy your sin?” She signs a document giving the convent the right to put her child up for adoption; then she and other unwed mothers work off what they owe in the laundry room. They’re allowed an hour a day with their child. Philomena’s is named Anthony. At age 3 he’s taken away. She hasn’t seen him since.

Why does Philomena tell her daughter, Jane (Anna Maxwell Martin), about the half-brother she never knew on the 50th anniversary of his birth? She still considers herself a good Catholic and for years thought that what she’d done was a sin, a great sin, so she’d kept it hidden. But wasn’t keeping it hidden a sin as well? Which was the greater sin? She didn’t know. So her gut decided.

Later, Jane is serving wine at a party when she overhears Sixsmith talking to friends, rather uncomfortably, about his plans for the future. He’d worked for the Blair government but left under a cloud. The cloud actually surrounded the Blair administration but most people just remember the cloud. Sixsmith is thinking about writing a book on Russian history—everyone’s lack of interest is a running gag in the film—so Jane tells him about her mother. He’s dismissive at first. Human interest stories, he says, are for “weak-minded, vulnerable and ignorant people.” Then he realizes the insult.

There’s a lot of this: Sixsmith acting slightly rude and/or academic in that Steve Coogan manner, then slightly abashed in that Steve Coogan manner. Philomena is his opposite. She’s sweet but slightly daft. Mostly it works. As here:

Jane [to her mother]: What they did to you was evil.

Philomena: No no no. I don’t like that word.

Martin [taking notes]: No, it’s good: Evil. [Looks up.] Storywise.

Or here:

Philomena: Do you believe in God, Martin?

Martin: [Exhales]Where do you start? I always thought that was a very difficult question to give a simple answer to. ... Do you?

Philomena: Yes.

Or the scene on the back of the airport cart when she goes on and on about the trashy book she’s just finished despite his complete lack of interest. But he’s polite. He says it sounds interesting and she pushes the book on him. He scans the back cover. “I feel like I’ve already read it,” he says dryly. Beat. “Oh, there’s a series.”

The even greater sin

In scenes reminiscent of Coogan’s mockumentary, “The Trip,” Sixsmith and Philomena drive to Roscrea to find of what they can. The nuns there are distant and unhelpful. The records of what happened to Anthony are gone, too, destroyed in the fire in the 1970s. He later learns the fire wasn’t a fire-fire but a burning of records.

Back in the 1950s, most Irish children were adopted by wealthy Americans, some of the few people in the postwar world who could afford the £100 pricetag; and while the British government isn’t helpful with its records, Sixsmith, who once reported from Washington, D.C., thinks they’ll have better luck with the Yanks. That’s the rationale for flying to the states. It feels unnecessary, but it furthers the road trip and the comedy of manners. In a D.C. hotel buffet, for example, Philomena is overfriendly with the Mexican staff (“I’ve never been to Mexico but I hear it’s lovely.” Beat. “Apart from the kidnappings.”), while Sixsmith isn’t friendly enough. But it’s there he finds the answer to her question. A friend emails an old newspaper photo from 1955 showing a Dr. and Mrs. Hess returning from Ireland with two adopted children, Michael and Mary. A quick internet search turns up Michael Hess, senior counsel in the Reagan and Bush Sr. administrations, who died of AIDS in 1995. Philomena has found her son only to lose him again.

That’s the dead-end. So where do you go?

To these questions: Did he miss me? Did he think about me? Did he try to find me as I tried to find him? That’s when the trip to the U.S. makes sense. They meet the sister, Mary (Mare Winningham, in a great, thankless performance), who seems to know little about the inner life of her brother, along with a few of Michael’s friends; but in Michael’s lover, Pete Olsson (Peter Hermann), they run into another dead-end. He refuses to talk to them, even after Sixsmith “doorsteps” him. It’s Philomena and her moral authority that wins the day.

She learns that not only did Michael try to find her, he visited Ireland and the convent. He met with the nuns, including Sister Hildegarde (Kate Fleetwood/Barbara Jefford), severe in manner and cat’s-eye glasses. He’s buried there. But they told her they didn’t know where he was, just as they’d told him they didn’t know where she was. They kept mother and child apart. Most movies are about absolutes, good guys and bad guys, so I took all of this with a grain of salt. “I’m sure it’s exaggerated for the movie,” I thought.

Nope. From Sixsmith’s 2009 Guardian article:

Separated by fate, mother and child spent decades looking for each other, repeatedly thwarted by the refusal of the nuns to reveal information, each of them unaware that the other was also yearning and searching.

On the return to Roscrea, Sixsmith is full of righteous anger and condemnation. That’s what the movies are often about, too: revenge. Philomena takes another path, and it’s her path that gives the entire movie meaning.

Notre Dame

“Philomena” isn’t perfect. Coogan, who wrote the screenplay with Jeff Pope, pushes the differences between the two characters to an unnecessary comic degree. He turns Sixsmith into too much of a Steve Coogan character and makes Philomena more daft than she probably is.

But Dench is perfect. We get several scenes from the 1950s to demonstrate what Philomena lost, but these, to me, are almost unnecessary. We know what Philomena lost. You just need to watch Judi Dench act.

Wednesday December 04, 2013

Movie Review: Before Midnight (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

September 4, 2012

Dear Jesse:

First, it was great meeting you and your family in Greece this summer. I was only there a week but I had a blast. Your boy Henry is very sweet and the twins are adorable.

Second, it’s a little intimidating writing a letter to a famous novelist such as yourself. I know, I know, there’s Gore Vidal’s line: “To speak today of a famous novelist is like speaking of a famous cabinetmaker or speedboat designer. Adjective is inappropriate to noun.” Even so, it’s intimidating. I never read your books (sorry!) but I did see the movies based upon them (sorry again!). “Before Sunrise” and “Before Sunset,” right? With Ethan Hawke as you and Julie Delpy as Celine? Don’t remember much about them, unfortunately. I remember conversations on a train and walking about in Paris and a reading at ... was it Shakespeare & Co.? Those movies were mostly dialogue about everyday matters. Maybe that’s why I don’t remember them. The everyday goes away.

Anyway, apologies about all that, and apologies for this massive presumption, but it’s the reason for this letter. I wish I’d told you this earlier but now this will have to do. Here it is.

Anyway, apologies about all that, and apologies for this massive presumption, but it’s the reason for this letter. I wish I’d told you this earlier but now this will have to do. Here it is.

Your wife is crazy.

I didn’t think so at first. I thought, “Ah, another couple dealing with the doodads and crises of parenting in the early 21st century.” I even had a little trouble with you at first. I thought you were too delicate around your son. Like you were seeking his approval when it should be the other way around. Then I remembered you were divorced and he lived with his mother, and it made sense. You’re trying to make up for lost time. In this manner, divorce makes children of parents and parents of children.

It was at dinner that I began to see the pattern. Those dinners were a little odd, weren’t they? A little too Woody Allen during his stilted, pretentious period. I liked the kids enough. And I loved Patrick and Natalia. Her line about how we’re just passing through? And you raised a toast “to passing through”? That was nice. Sure, Stefano couldn’t get away from the topic of sex while Ariadni played her usual game of self-satisfied gender politics, but at least you felt the rules in their relationship. No one ever went out of bounds.

Your wife, Celine, kept going out of bounds.

Someone would say how the meeting story of you and Celine was romantic and you agreed and Celine immediately disagreed. Someone would say how your girls were beautiful and you thanked them and Celine immediately disagreed. Remember when Henry was out and about on the island and he called Celine’s phone and she wouldn’t put you on? I’d never seen that before. Another time she asked you some theoretical question—if you’d met on the train today, would you still talk to her?—and dissed your answer. She said, “I wanted you to say something romantic and you blew it.” But whenever you did say something romantic she dismissed it, so I didn’t see how you could win.

She kept cutting into you with these little cuts, about little things: the amount of housework you did, the attention you paid, how self-obsessed you were. Then she’d take out the cleaver and try to lop off your head. Sorry, but it was brutal to watch.

There was such hate in her eyes. That’s the thing. I couldn’t see the love there. Nowhere. You kept trying to make it work and she would come back at you with hate.

She kept reading two or three steps ahead into everything you said. Does she always do this? And is she right? I’m curious. Because you’d say something and she’d make this assumption about what it really meant, and she’d wind up objecting to something that wasn’t even there. Like after Henry left. You were talking about missing him, and missing his years growing up, and how he threw a baseball like a girl because you weren’t around to teach him—which he totally does—but how there was no solution. Henry wouldn’t be allowed to live with you in Paris and you couldn’t move to Chicago to be with him every other weekend because it would disrupt the lives of Celine and the girls. But that’s what she assumed you meant. And the daggers came out.

Have you talked to her about this? This tendency to read three steps ahead? To assume this much? Because it’s not even a good strategy. To attack someone where they aren’t? Every battle that does that, loses. Or does she do this to prevent you from getting there? She attacks where you aren’t to prevent you from going to that place?

Remember that conversation we had about how men always compare themselves to other famous men? Fitzgerald did this by age X and Balzac by age Y and why aren’t I doing that? That felt true. But then she said something like, “Women don't think that way as much.” WTF? That’s the main neuroses, isn’t it? I’m fat, I’m ugly, my hair is too straight. Or too curly. I’m not wearing the right shoes. I’m not Beyoncé or Angelina or Kate. But she probably meant, you know, women outside of show business, because then she said something like, “The women who achieve anything in life, you first hear about them in their 50s, because they were raising kids before then.” So obviously not Beyoncé. She’s talking about someone like Ruth Bader Ginsberg ... who was arguing cases before the U.S. Supreme Court in her thirties. Or Flannery O’Connor ... who wrote “Wise Blood” in her twenties.

No, I know. She was talking about herself. Because that’s what she does. She was laying out the hope that her achievement in life is not being wife to you, or mother to two girls, but something else. Now to me—and I tried to tell her this—but to me the most important thing men and women can do in this life is raise children, and raise them well, but I’m still a fan of maintaining hope for other achievements, too. It keeps us going. In a way, you and Celine regret opposites: You, who have published three novels, regret not parenting enough, and she, mother of two girls, regrets not “achieving” enough. So there’s conflict. That’s inevitable. But you seem to blame you for not parenting more while she seems to blame you for why she hasn’t achieved more. And she blames you without mercy.

I haven’t even told you the worst part yet.

Celine and Patricia and I went on a hike one day. Celine, again, wouldn’t shut up, just went on and on about herself. At some point she talked about some quote someone put on the refrigerator at work with those poet/magnet thingees. Something like, “Women explore for eternity in the vast garden of sacrifice.” Crap, right? She thought it was meaningful. More, she thought it related to her. Not just her mother or grandmother, or any of the women who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago—but her: a pretty French girl born in Paris in 1970. She thinks she’s spent her pampered life in “a vast garden of sacrifice.” She sees herself, despite all evidence to the contrary, as a symbol of oppressed women everywhere. And she sees you—and this was the really weird part—as a symbol of tyrannical men everywhere. She compared you to Dick Cheney and George W. Bush! She said you were a proponent of “rational thinking” but then so were the Nazis during the Final Solution. I mean, holy fuck. I had to walk away at that point.

I probably shouldn’t even have written this letter. I probably won’t send it. I just had to let it out. In the past, you’ve written about your relationship with Celine, and I wouldn’t be surprised if you write about this summer: How you and Celine were in this beautiful place but stuck in this awful situation, which she kept trying to destroy and you kept trying to repair. Maybe they’ll make another movie about it. “Before Dinner”? “Before Dusk”? “Before the Final Solution”?

Anyway, I hope to see you again. Maybe in another nine years? If so, I hope—and this is a bad thing to hope—but I hope you’re on your own. I hope you’re finally free of Celine and that awful, awful decision you made to talk with her on the train to Paris in 1994. Because no man deserves the amount of grief you’re putting up with. To be honest, it’s a little embarrassing.

Best,

Erik

Monday December 02, 2013

Movie Review: Oldboy (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Park Chan-wook’s “Oldboy” (2003), starring Choi Min-sik and Kang Hye-jeong, is the one of the greatest revenge movies ever made. Spike Lee’s “Oldboy,” starring Josh Brolin and Elizabeth Olsen, is not.

The new “Oldboy” is both more grounded and less believable. It’s less dreamlike, less cartoonish, less comic, and packs less of an emotional wallop. It give us more of Joe Doucett (Brolin) acting like a drunk asshole, more of Joe imprisoned in the room, and a greater subterfuge about the love interest (Olsen), but it’s not as good, not as clever, and obviously not as original. It corrects some of the mistakes of the Korean version but makes its own. It shortens the length of the movie by 16 minutes but hardly to its advantage. As the climax looms, we think, “Already?”

Admittedly remaking a classic is a tough gig.

The prison

Joe Doucett is an ad executive and alcoholic, who, as the movie begins, blows a deal by coming onto his client’s wife. Afterwards, he gets massively drunk, roams Chinatown, buys a cheap Buddha gift for his 3-year-old daughter, throws up on himself, and knocks on the door of the bar of his friend Chucky (Michael Imperioli).  Then a beautiful woman with an umbrella appears, beckons him, and Joe disappears. All that’s left behind is the Buddha.

Then a beautiful woman with an umbrella appears, beckons him, and Joe disappears. All that’s left behind is the Buddha.

He wakes in a hotel room with the shower running. He assumes it’s the umbrella woman but nobody’s there. His clothes are gone, there’s no phone, no room service. At first he thinks he’s simply locked in; then, as food and vodka appear, he realizes he’s being kept prisoner in the room. We realize, meanwhile, that the Korean version didn’t give us this. It went right to being imprisoned for two months, as its main character, Oh Dae-su (Choi Min-sik), veers between rage and catatonia. Both responses come off as comic. That’s part of the tension in watching: not laughing at this man in his horrible predicament. Spike Lee doesn’t give us this. So there’s less tension.

What does Joe do in his imprisoned hotel room? He drinks, he cries, he jacks off. After this last, gas fills the room, and some time later he finds out via the TV news that his ex-wife has been raped and murdered and the irrefutable evidence points to ... him. He’s now a wanted fugitive.

After a few years he gets serious. He stops drinking, gets in shape, readies himself for revenge. He’s tunneling his way out, a la Andy Dusfrene, but at the last moment gas fills the room again. Except when he awakes, he’s out, he’s free. Where? Korean version: on a rooftop. U.S. version: in a coffin in the middle of a field. OK. And there’s the woman with the umbrella again. OK. It’s amazing how she hasn’t aged. Or maybe this is a different woman.

It’s amazing how he hasn’t aged. Joe actually looks better now than when he went in. He also seems saner. Every one of these points is at odds with the Korean version; every one seems wrong.

He follows the umbrella girl until ... well, now it’s a homeless man, standing in line for free health care, and the volunteer nurse on staff is Marie Sebastian (Olsen), who gets caught up in Joe’s life and story. As does Chucky. As does Adrian (Sharlto Copley of “District 9”), the man who imprisoned him, who sets him on a 48-hour mission to find out the answer to these two questions: who is he and why did he imprison Joe for 20 years? If he can answer these, his daughter, now 23, and a cellist somewhere, will live, he’ll be given evidence to clear his name, he’ll be given, what is it, $20 million in diamonds? Plus he’ll get to watch Adrian put a bullet through his own head. Nice deal. He takes it.

The larger prison

So how else does the U.S. version differ from the Korean version? Well, the owner of the private jail, Park there and Chaney here (Samuel L. Jackson), isn’t tortured by teeth extraction; instead, Joe cuts out bits of his neck and literally pours salt in the wounds. There’s less back-and-forth with him, too. Park and his men keep turning up, Chaney less so.

The backstory of the villain (Adrian/Lee Woo-jin) is also different. Korean version: Lee had sex with his sister at school, Ou Dae-su saw it, told his friend, who told others, and on and on until there was scandal and suicide. So Ou Dae-su, a despicable man, suffers for a crime he didn’t commit. U.S. version: Joe witnesses sex, yes, but between the sister and an older man, who turned out to be the father. Joe didn’t know that then, but he still spread the story, and the girl was still hounded, and eventually the entire family, happily engaging in incest with the father, was forced to flee to Luxemburg, where Daddy finally lost it and killed them all. Adrian was only wounded.

Now before I go on to other changes, let me say, emphatically, to anyone who hasn’t seen theKorean version: Go watch it. Now. It’s streaming on Netflix. If you keep reading this, you will discover one of the great twist endings in movie history. It will be like knowing what Rosebud was. So please, if you haven’t seen the movie yet, leave.

Are we good? Don’t say you haven’t been warned.

Another difference is the way the new “Oldboy” presents what happened to Joe/Ou’s 3-year-old daughter. Korea: He gets a slip of paper saying she was adopted by a couple in .... was it Switzerland? She’s out of the picture. In the U.S. version, we see her on television over and over again. She keeps showing up on one of those crappy “unsolved crime” shows, which Joe keeps watching while imprisoned. She grows to be a beautiful 23-year-old cellist. Why this change? One: American children don’t get adopted abroad. Two: the greater subterfuge—and it is subterfuge—is there less to fool Joe than to fool us.

Except ... One of the things I liked about the Korean version is that I suspected briefly who Mi-do (Kang Hye-jeong) was. “He should be careful,” I said to Patricia. “That girl is his daughter’s age. She could be his daughter.” I’m careful this way. I’m good with math. But the thought went away. It flashed in my head, and the story picked up, and I stopped thinking about it.

This has happened to me a couple of times watching movies: flashing on the answer, losing it in the story, and then—boom—there it is. When I first saw “The Crying Game,” I thought maybe the dude was a lady; then it went away; then there it was. With Robert Altman’s “Nashville,” I felt a vibe of assassination. I don’t know why. But then it went away. Then boom. It’s almost a kind of subconscious foreshadowing. It’s one of those mysteries of movies, and if you have it you don’t want to mess with it—it’s actually more effective, more resonant, than completely fooling your audience—but in the new “Oldboy” they mess with it. Since the subterfuge is greater, I can’t imagine anyone new to the story engaging in this kind of subconscious foreshadowing.

In both versions, by the way, the villain tells the hero he asked the wrong question: Not why did I imprison you but why did I let you go? But here’s a better question: Why did I let you go after 15/20 years? The length of time, it turns out, is the whole point.

Park’s “Oldboy” is a great revenge fantasy because the revenge isn’t extracted by the man who was imprisoned but by the man who imprisoned him. And the 15 years isn’t the revenge, it simply sets up the revenge. The 15 years is prelude. Enough time has to pass to allow the revenge to happen: to make Ou guilty of the crime that sent Lee Woo-jin’s sister to her death: incest. That’s brilliant. Equally brilliant, equally painful, is Ou’s reaction. He grovels and acts the dog. He literally cuts out his own tongue to please the man who imprisoned him so he won’t tell the daughter what really happened. The dream has become a nightmare; and unlike Ou’s imprisonment, it won’t ever end.

The U.S. version screws this up, too. Josh Brolin is a good actor but he can’t grovel. And Joe certainly doesn’t cut out his own tongue. Instead, even as Adrian kills himself, Joe takes the diamonds, gives most to Marie along with a carefully worded farewell note, and the rest goes to Chaney so he’ll lock up Joe for the rest of his life. Joe is now his own imprisoner. And he smiles at the camera.

It’s not a bad end. It recalls long-held prisoners who want the comfort of the jail cell again. But it doesn’t resonate the way the Korean version resonates.

Recidivism

I think the biggest mistake in Spike’s version was losing the dream/nightmare quality of the Korean film, the horror/comic fable of it all. This version takes itself a little too seriously. Which I guess is what you do when you remake a classic. But it doesn’t serve the final product.

Or maybe it does. We still have the original version, after all, and the U.S. version, despite the talent involved, is no competition. It will fade, disappear from view, leaving only the Korean classic. That’s the one people should see anyway.

Tuesday November 26, 2013

Movie Review: The Internship (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Here’s a conversation between Patricia and I during the last five minutes of “The Internship,” starring Vince Vaughn and Owen Wilson:

Me: Why is everyone else cheering? They just lost. They won’t get jobs now.

Patricia: And what’s the stripper doing there?

That pretty much sums up the movie. The few choice jobs in the digital age are gone ... and what’s the stripper doing there?

Has there been a worse year for comedies? Hollywood keeps trying to make us laugh from situations that cause massive social anxiety: identity theft, college admission, Burt Wonderstone. In “The Internship,” it’s obsolescence in the digital age. Wucka wucka.

I get it. Our heroes dream and persevere. They overcome and work as a team and win. But the anxiety is too real while the victory too fake. The filmmakers (director Shawn Levy; screenwriters Jared Stern and Vince Vaughn) have taken the American nightmare, shoved it through the Hollywood dream factory, and this is what came out the other end.

Selling watches in 2012

Billy McMahon (Vaughn) and Nick Campbell (Wilson) are mid-40s watch salesmen who don’t know what time it is. They don’t even know their company has folded. It takes a former customer to tell them that.

Immediate thought. Sales? That’s a transferable skill. They should do well. Hell, if they can sell watches in 2012, they can sell anything.

Immediate thought. Sales? That’s a transferable skill. They should do well. Hell, if they can sell watches in 2012, they can sell anything.

Except for the movie to work, they can’t get jobs; and because they can’t get jobs, they’re forced to roll the dice as interns at Google, where they join a team of misfits and compete, for a job, against a bunch of other teams, including a team led by a true douchebag, Graham Hautrey (Max Minghella), who has it in for our team of sad-sack misfits. And while our team starts poorly, eventually, in the Hollywood tradition of misfit teams, they come together and begin to win and have a chance. Ah, but team leader Billy lets them down and gives up and walks away. But then he’s called back! At the last second! And they finally win! And there’s the stripper!

So it’s like “Monsters University” but more cartoony. And with a stripper.

Who are these other misfits? There’s the ostensible leader, Lyle (Josh Brener), a nerd who uses hip-hop slang and has the hots for the part-time Google dance instructor Marielena (Jessica Szohr); Stuart (Dylan O’Brien), who can’t bother to look up from his smartphone; Neha (Tia Sircar), a supercute girl who likes nerdy things (cosplay, etc.) but somehow still can’t get a date; and Yo-Yo (Tobit Raphael), the home-schooled son of a Tiger Mother, who pulls at his eyebrow when he feels like he’s done something bad.

I liked Yo-Yo. He felt new.

How do they come together as a team? Do I have to say? Actually, see if you can pick out the most absurd element on their road to victory.

They go partying. Yep. They wind up in a Chinatown restaurant, where Billy orders their meal in Mandarin, and then at a high-end strip club, where they do shots, and get lap dances, and where Neha takes a shower with her clothes on and Lyle hooks up with Marielena, who, oops (she’s so embarrassed!), is a high-end stripper and lap dancer as well as being the part-time Google dance instructor. So if Google paid her more, would she not have to strip? No one raises that point. But of course she’s interested in Lyle! What high-end lap-dancer doesn’t want a serious relationship with Dilton Doiley? Then there’s a fight (over Marielena), and afterwards, as dawn breaks beautifully over the Golden Gate Bridge, our team, recounting its crazy night, comes up with an app that wins the next event.

So: What’s the most absurd element from this crazy night? The Lyle/Marielena relationship? The fight? The fact that Neha was totally cool being in a high-end strip club where women walked around in lingerie sucking on men’s fingers?

For me it’s the Mandarin. It means that Billy is in sales, and he speaks Mandarin, and somehow he still can’t get a job.

Does Hollywood know what year it is?

Cheering for losing

There are cameos by Will Ferrell and Rob Riggle, both playing major assholes, and Nick winds up romancing a beautiful Google executive, Dana (Rose Byrne), who just never had time for a relationship but now suddenly does with a half-hearted Owen Wilson. I could barely watch their scenes together. They were so awful, I just wanted to crawl away.

Sales turns out to be the final event, which is perfect for our team. And at the last minute they nail the sale, the douche is shown up, and everyone at Google, including the other intern teams who have just lost, and thus lost the chance at their dream job, stand and cheer for our team, because that’s what always happens in the real world. Then everything else falls into place. Nick winds up with Dana, Stuart with Neha, and Yo-Yo tells off his tiger mom, who looks proud that he does so. Oh, and Lyle winds up with the stripper. Because that’s what she’s doing there. Because that relationship has no chance of not failing.

Google “shitty movie.”

Monday November 25, 2013

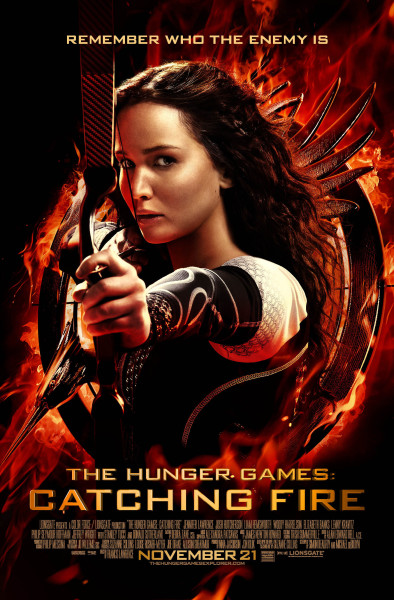

Movie Review: The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It’s a rigged game.

I don’t mean the Hunger Games. I mean “The Hunger Games.”

The film’s creators, or possibly author Suzanne Collins (I’m not sure which since I haven’t cracked a spine in the series), rig the first game, “The Hunger Games,” by ensuring that Katniss Everdeen (Jennifer Lawrence) never loses favor with us by never actually killing anyone in cold blood in this kill-or-be-killed world. She triumphs without real blood on her hands.

Now, in the sequel, “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” the game really is rigged—this time by the other characters, particularly the game’s creator, Plutarch Heavensbee (Philip Seymour Hoffman). He’s using it, and Katniss, as a means to foment rebellion. As a result, once again she doesn’t have to kill in cold blood. Once again, when given the choice between murder and mercy, she goes with mercy. Once again, this never backfires on her.

Now, in the sequel, “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” the game really is rigged—this time by the other characters, particularly the game’s creator, Plutarch Heavensbee (Philip Seymour Hoffman). He’s using it, and Katniss, as a means to foment rebellion. As a result, once again she doesn’t have to kill in cold blood. Once again, when given the choice between murder and mercy, she goes with mercy. Once again, this never backfires on her.

But there’s a bigger reason why “The Hunger Games” is a rigged game: for a dictatorship, the Capitol comes pretty weak and dumb.

Dictatorship and distraction

Early on, for example, Plutarch gives Pres. Snow (Donald Sutherland) a way out:

Snow: She has become a beacon of hope for them. She has to be eliminated.

Plutarch: I agree she should die but in the right way. At the right time. ... Katniss Everdeen is a symbol. We don't have to destroy her, just her image. Show them that she's one of us now. Let them rally behind that.

The districts are already beginning to rebel. So he suggests a crackdown with public whippings and executions, then show these on television interspersed with shots of Katniss, the supposed rebel hero, shopping, trying on make-up, trying on a wedding dress. “They're gonna hate her so much,” he says, “they just might kill her for you.”

Great idea. So what happens to it?

Barely anything. The troops crack down on District 12, Gale Hawthorne (Liam Hemsowrth, Thor’s brother) tackles Commander Thread (Patrick St. Espirit), and gets a public whipping for it. But guess who comes to the rescue? Katniss. And guess who comes to her rescue? Haymitch (Woody Harrelson). And guess who comes to his rescue? Peeta (Josh Hutcherson). And that’s that. She’s a heroine all over again because everyone saw enough of her bravery on television. So now Pres. Snow wants a new plan, even though it never looks like the first plan went into effect. And that’s when Plutarch reveals that all the previous winners, including Katniss, compete for the 75th Hunger Games. Which is why we get Katniss is another Hunger Games.

That’s one major problem. Here’s another. Early on, Gale says this to Katniss:

People are looking to you, Katniss. You've given them an opportunity. They just have to be brave enough to take it.

Here’s the thing, though. They are brave enough to take it. They are rebelling. The one who isn’t brave enough is Katniss. She keeps pulling back. Sure, Pres. Snow has threatened her mother and sister and hunky hunk Gale, but so what? She has a chance to change an awful, awful world. She just doesn’t grab it. Instead she encourages folks forward, like the old black man, who gives her the third-fingered salute and four-note whistle, and he gets executed before her distraught eyes.

Instead of trying to do something, Katniss plays along with the ruse: that she and Peeta are in love and about to get married and yadda yadda. Why does she do this again? I’ve actually forgotten. At one point, Haymitch tells her this:

From now on, your job is to be a distraction so people forget what the real problems are.

But a distraction to which people? Those in the districts or in the Capitol? Or both? It seems like it should be in the districts but they never seem distracted. They never seem fooled. They never forget who the true enemy is.

I’m sorry, but the more I think about this movie the dumber it gets. If you have dictatorial powers, as Snow does, and control over the media, as this government does, then how can you not besmirch a name? It’s called propaganda. Do we need FOX-News to show him how it’s done?

In 1985 Neil Postman published a book, “Amusing Ourselves to Death, “ in which he argued that of the two great dystopian novels from the first half of the 20th century—Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” and George Orwell’s “1984”—it was actually the former, whose weapon of governmental control was distraction, rather than the latter, whose weapon was dictatorship, that was the more prescient and more deadly. The point is this: the Capitol has both dicatorship and distraction—and a rebel hero uninterested in rebellion—and they still can’t control her.

Talk about a rigged game.

The most successful formula in movie history

Anyway there goes Katniss into another Hunger Games. Here are the bad dudes from District 1. Here’s a bit of practice. Here are possible allies. Here are the interviews conducted by cloyingly sentimental host Caesar Flickerman (Stanley Tucci, channeling Jiminy Glick). And off they go.

The acting talent here is amazing for this type of movie. Along with the previously mentioned names, Elizabeth Banks is choice as the gloriously frivilous Effie Trinket; and both Amanda Plummer and Jeffrey Wright are perfect as a half-cerebral, half-crazy Hunger Games team.

So what is it about this movie, this series, that makes it so popular? People talk about what a positive role model Katniss is, blah blah, but I think it boils down to the oldest, most successful formula in movie history: a strong woman having to choose between two men against a backdrop of tragedy. That’s “Gone with the Wind,” “Sound of Music,” “Titanic,” the “Twilight” series, and now “Hunger Games.” And like the “Twilight” series, the final “Hunger Games” is split into two parts: one for 2014, one for 2015.

I hope that distracts you enough that you forget what the real problems are.

Wednesday November 20, 2013

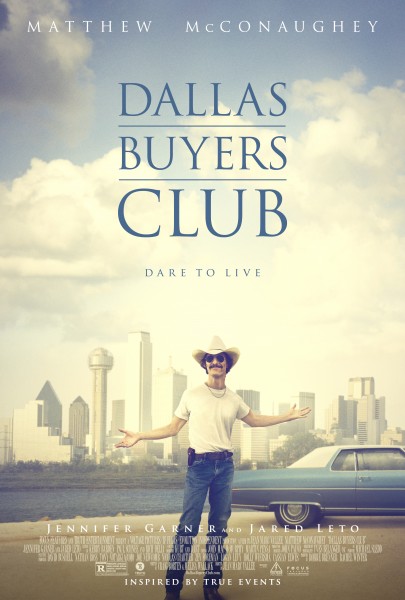

Movie Review: Dallas Buyers Club (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

There's your best actor. Maybe supporting, too.

That’s what I kept thinking watching “Dallas Buyers Club,” directed by Jean-Marc Valée (“The Young Victoria”) and written by Craig Borten and Melisa Wallack. For a time I was even thinking best picture, maybe, possibly, a candidate anyway, but then the movie lost something in its final third. Was it the battle between Ron Woodruff (Matthew McConaughey) and the various government agencies (IRS, FDA and DEA)? Was that too obvious? Was it the absence of Rayon (Jared Leto) after her death? Was it the presence of Jennifer Garner as Dr. Eve Saks? Garner was out of her element here. She came onscreen and the energy just drained away.

But McConaughey? Hoo boy.

Gotta die somehow

He plays a good ol’ boy: a Texas electrician, part-time rodeo rider, and full-time racounteur. The first images we see are of a bucking bull from behind the fence. Since we also hear snorting, we think we’re getting the bull’s perspective, but it’s actually Woodruff banging a girl in the bull’s pen. He looks a bit thin and tired and has a persistent cough. Bad sign. A cough in the first act is like the gun in the first act.

He plays a good ol’ boy: a Texas electrician, part-time rodeo rider, and full-time racounteur. The first images we see are of a bucking bull from behind the fence. Since we also hear snorting, we think we’re getting the bull’s perspective, but it’s actually Woodruff banging a girl in the bull’s pen. He looks a bit thin and tired and has a persistent cough. Bad sign. A cough in the first act is like the gun in the first act.

AIDS comes into the conversation quickly via headlines about Rock Hudson. Woodruff is hardly sympathetic:

Woodruff: You hear Rock Hudson was a cocksucker?

Friend: Where’d you hear that?

Woodruff: It’s called a newspaper.

He’s more immediately concerned about a rodeo bet he made that went awry. He’s running from the men he owes money to—nearly a dozen cowboys, from the looks—when he runs into a friend, a cop, Tucker (Steve Zahn), who’s had to deal with this before and won’t protect him now. So Woodruff gets inventive. He decks Tucker. On the ride home, Tucker tries to give him some sound advice about his reckless nature and how it’ll likely get him killed. “Gotta die somehow,” Woodruff says in that smooth McConaughey voice. He says it like he’ll live forever.

A few days later, there’s an accident at work and he’s taken to the hospital, where he’s told by two doctors wearing surgical masks that he has both HIV and full-blown AIDS. His reaction is interesting. “You’re fucking kidding me,” he says. When Dr. Savard (Denis O’Hare) recounts the ways people contract HIV, beginning with homosexual sex, his reaction gets more interesting. “I ain’t no faggot, motherfucker!” The doctor remains calm and gives him 30 days to live but Woodruff is still on the first two stages of the five stages of grief: denial and anger. “There ain’t nothing out there that can kill Ron Woodruff in 30 days!” he shouts.

Over the next 30 days, he’ll go through the next two stages: bargaining and depression. At the library, he researches the disease, realizes how he contracted it (sex with an IV drug user, I believe, but it’s a bit murky), and searches for a cure that doesn’t exist. AZT is the drug bandied about, and trials are being done, but there’s a chance you’re in the control group—the sugar pill group—and he’s not willing to take that chance. So he gets inventive again. At a strip club he sees an orderly from the hospital and bribes him to get him AZT drugs, which he washes down with whiskey and cocaine.

During this period, friends abandon him. There’s a great scene where he goes to his usual bar, orders his usual drink, heads to his usual table of friends. But they’re no longer his friends. They call him faggot. He’s immediately ready to fight them all, and they want to kick his ass, but an interesting dynamic occurs. No one wants to touch him. No one wants to get within 10 feet of him. He’s a like-poled magnet: He takes a step forward and they a step back. He spits on them and curses the place as he leaves. He’ll do this a lot during the movie. I lost track of the number of times he left a room shouting, “Fuck all y’all!”

By the end of the 30-day period he’s left with nothing: no friends, no home (he finds his trailer home padlocked, with FAGGOT BLOOD spraypainted on the side), and the AZT is only making him worse. Plus it runs out. But the orderly gives him an address in Mexico, outside the realm of the FDA, so that’s where he heads. Because Ron Woodruff may be a lying homophobic asshole, but in this movie he never winds up on the fifth stage of grief: acceptance. He thrives at stages 2 and 3: anger and bargaining.

FDA, DEA, etc.

It’s in Mexico that the story really begins. I didn’t know this going in. All of this came as a pleasant surprise for me.

Near death, he’s saved, for the time being, by Dr. Vass (Griffin Dunne, in a great cameo), who lost his license in the states, and who counsels against AZT, which destroys all cells, both good and bad. Instead, Ron should concentrate on building up his immune system with vitamins, zinc, and aloe. He also recommends DDC, a less-toxic anti-viral, and Peptide T, a non-toxic protein, neither of which are approved by the FDA. He thinks about all the AIDS sufferers in Dallas and says, “You could make a fortune off this stuff,” and a light goes off. CUT TO: filling his trunk with drugs for the trip back. There he starts the Dallas Buyers Club, modeled after similar clubs in New York. Since it’s illegal to sell non-FDA-approved drugs, he sells memberships into a club, which dispenses the drugs.

He partners with a transexual, Rayon, and soon has lines forming outside the motel room they’ve set up. He also attracts the attention of the usual government agencies: FDA, DEA, etc. A battle is enjoined and lessons are learned. He becomes more tolerant of gay people, for example. He keeps using the epithet “Cocksucker” but now it’s for FDA officials. That’s the journey he takes: from anti-gay to anti-government.

Some have complained, or celebrated, that this makes the movie too Tea Party, but for me it’s just too simplistic. It’s the brash homophobe protecting the poor gay folks who can’t protect themselves. The government gets blamed but not the infamously homophobic Reagan administration. Some of the casting doesn’t help. When I first saw Denis O’Hare as Dr. Sevard, I thought, “Oh, it’s the guy who usually plays a corporate asshole. Nice that he gets to play a ... No, he’s a corporate asshole here, too.” Kevin Rankin, the white-trash dirtbag of “White House Down” and “Breaking Bad,” plays a white-trash dirtbag. Michael O’Neill, who usually plays a bureaucratic douche, plays the main FDA douche. Etc.

But Jared Leto is a revelation and McConaughey is uncompromising in his portrayal. He’s corralled his charm and energy into the service of full-dimensional characters in good movies.

Getting thrown

I did like the scene at the end before the district court in San Francisco. Woodruff has sued to use and sell non-FDA approved drugs but loses. It’s the language of the judge that I appreicated—the difference between law and justice:

Mr. Woodroof, there is not a person in this courtroom who is not moved to compassion by your plight. What is lacking here is the legal authority to intervene. I’m sorry.

What do you call that? A liberal judge not legislating from the bench.

I also like the final images: Woodruff riding a bull at a rodeo. You wonder if it’s current, if he’s gotten well enough to do that again, but it’s both flashback and metaphor. This is what he’s been doing the entire movie, and he finally gets thrown on September 12, 1992. He was given 30 days and took more than 2,000.

But then we get another title that dampens the effect of much of the movie: we’re informed that lower doses of AZT, the devil drug in the movie, wound up leading to the cure we currently have. So it was hardly a devil drug; it was just dispensed improperly. It confuses the movie’s clean formulaic lines, suggesting that maybe they shouldn’t have been so clean and formulaic.

But “Dallas Buyers Club” is still a movie worth seeing—for its performances, its energy, the fact that there’s comedy and adventure in a movie about AIDS. It’s also a good reminder of what AIDS and homophobia felt like 30 years ago.

Monday November 18, 2013

Movie Review: Parkland (2013)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Well, “spoilers.”

The saddest American day of my lifetime occurred when I was 10 months old. We keep telling it again and again. We keep probing the wound. Sometimes I think we like it. It makes us feel something even if that feeling is overwhelming sadness and horror for all that was lost. In this way the assassination of Pres. John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963 in Dallas, Texas, is, for Americans, what the Onion Cellar in Gunter Grass’ novel “The Tin Drum” is for Germans: a place to go to cry.

But since we keep telling it, how do you tell it anew?

Writer and first-time director Peter Landesman does just that in “Parkland,” a 90-minute film based on Vincent Bugliosi’s book “Four Days in November.” Landesman doesn’t tell the story from the perspective of the principal characters; he tells it from the perspective of the people whose lives that day were peripherally if monumentally affected: Abraham Zapruder, who shot the 8mm footage of the assassination; James Hosty, from the Dallas FBI office, who had been tracking Oswald, and who, in the aftermath, was blamed and even fingered by conspiracy theorists; Robert Oswald, brother of Lee, whose family name was forever besmirched; and the various doctors and nurses at Parkland Memorial Hospital, who tried to save both Pres. Kennedy that Friday and his assassin two days later.

History’s supporting players

It’s a movie about history’s supporting players starring great supporting actors:

It’s a movie about history’s supporting players starring great supporting actors:

- Marcia Gay Harden, who won the supporting actress Oscar in 2000 for “Pollock," plays Doris Nelson, the supervising nurse at Parkland.

- Paul Giamatti, nominated in 2005 for “Cinderella Man,” plays Zapruder, a man of enthusiasms, an immigrant who loved America and then unknowingly but unflinchingly filmed one of its great horrors.

- Billy Bob Thornton (supporting nom for “A Simple Plan” in 1998) is Forrest Sorrels, head of the local FBI office.

- Jackie Earle Haley (“Little Children” in 2006) plays the priest who administers last rites.

- Jacki Weaver (“Animal Kingdom” in 2010 and “Silver Linings Playbook” in 2012) is spooky as the Oswald matriarch, Marguerite, who insists that her son was an American agent who had done a great deed, and that her family would “never be ordinary again.”

Add in James Badge Dale as Bob Oswald, Ron Livington as Hosty, Colin Hanks as Dr. Malcolm Perry, the attending physician, and a couple of former teen heartthrobs—Zac Efron as the resident doctor who first began working on Pres. Kennedy, and Tom Welling as Roy Kellerman, the secret service agent who rode in the presidential limousine—and you’ve got quite a cast. Everyone’s good. A few (Harden, Weaver) are outstanding.

The details make the movie. Zapruder knew immediately. Everyone else is rushing around but he knew. I like the way Dr. Perry, in a board meeting, says “Five minutes” when told he’s needed in O.R. Nothing was ready. Secret service agents had to demand a stretcher and then rush through the narrow hallways to the small operating room. Blood was everywhere and on everyone. Zapruder is horrified by the “undignified end for a very dignified man” but he doesn’t know the half of it. Kennedy’s clothes are cut away during the futile attempt to revive him. Jackie continues to clutch portions of her husband’s skull and brain, as if they will be needed to put him back together. There is a shouting and shoving match in the operating room between Kellerman, who insists on bringing the body back to Washington, D.C., and Earl Rose (Rory Cochrane), the Dallas coroner, who insists on performing the autopsy there, as required by law.

The body, in a casket, is then rushed to Love Field and a dozen men shakily, almost frantically carry it onto Air Force One. Chairs have been removed in anticipation (“We’re not carrying it below like a piece of luggage!” one man says), but a partition still has to be ripped out by Kellerman to make the turn. There’s such a rushed, frantic quality to all of this, it’s as if they’re making a getaway. It’s as if they’re trying to escape a nightmare.

We also get moments of dignity and solemnity. The last rites, for example; and the crucifix retrieved by Doris Nelson from her locker.

Three funerals