Movie Reviews - 2011 posts

Wednesday September 21, 2011

Movie Review: Barney's Version (2011)

SPOILERS, BOYCHIK

We first see the film’s protagonist, Barney Panofsky (Paul Giamatti), 65, waking beside empty whiskey bottles and spent cigars, and groaning. He phones a man named Blair (Bruce Greenwood), asks to speak to “my wife,” then promises nude photos of said wife so Blair “can see what Miriam looked like in her prime.” Later that day, when his grown daughter informs him that Blair had a heart attack that morning, Barney is unsympathetic. “Putz,” he says. That evening he goes to a bar to drink and watch the hockey game. But at the bar sits an old enemy, a retired Irish cop, O’Hearne (Mark Addy), who has written a book accusing Barney of a long-ago murder. “Now the whole world is going to know what a cocksucking murderer you are,” O’Hearne says two inches from Barney’s face. “You could use a mint,” Barney replies with surgical precision.

Fun! We seem to be promised the story of a tough, foulmouthed Jew.

Unfortunately, we don’t see that guy much. For most of the movie, which includes long flashbacks of a ramshackle life, Barney is a bit of a putz himself.

In the late ’60s and early ‘70s, Barney hangs in Italy with friends, including Boogie (Scott Speedman), a handsome, talented, would-be novelist. There’s wine and beautiful Italian women (for Boogie anyway), but Barney, against Boogie’s advice, gets married to Clara (Rachelle Lefevre), a brassy, insulting woman who is pregnant with his child. He does the right thing even though she makes jokes about his three-inch penis. When she gives birth, and the baby is black, she tells him, from her hospital bed, “Oh Barney, you really do wear your heart on your sleeve. Now put it away—it looks disgusting.” When he leaves her for good, she kills herself. Guilt laps up on him.

In the late ’60s and early ‘70s, Barney hangs in Italy with friends, including Boogie (Scott Speedman), a handsome, talented, would-be novelist. There’s wine and beautiful Italian women (for Boogie anyway), but Barney, against Boogie’s advice, gets married to Clara (Rachelle Lefevre), a brassy, insulting woman who is pregnant with his child. He does the right thing even though she makes jokes about his three-inch penis. When she gives birth, and the baby is black, she tells him, from her hospital bed, “Oh Barney, you really do wear your heart on your sleeve. Now put it away—it looks disgusting.” When he leaves her for good, she kills herself. Guilt laps up on him.

Cut to: Montreal,1975, where Barney is running Totally Unnecessary Productions, which produces a long-running Canadian soap opera. He’s also about to get married again to a Jewish hottie (Minnie Driver) whose her father doesn’t approve of him, and approves even less of Barney’s father, Izzy (Dustin Hoffman), a former beat cop.

Can I pause for a moment to say how much I love Dustin Hoffman? I don’t know if he lights up the screen but he lights up me. He shows up and I beam.

He seems to be playing more overtly Jewish these days. Here, at a dinner gathering with the rich family of Barney’s fiancée, he’s all smiles and good will and blunt charm. He says to Barney’s fiancée, “You are one sweet casserole,” and encourages them to “get to schtupping.” The father of the bride doesn’t think much of this working class man, and says something vaguely and unnecessarily insulting, which he doesn’t think Izzy will understand. But Izzy gives him a look. It’s a look I’ve seen Dustin give in other movies. It’s as if both injury and civility are competing for control of his face. It’s a look that says: “I am smart enough to recognize your insult, I am sensitive enough to be injured by your insult, but I am strong enough to look you in the face and civil enough to keep smiling.” It’s the most human of faces. It’s why Dusty is my guy. Long may he act.

At Barney’s wedding, between attempts to get sloshed and watch the Stanley Cup finals (Montreal vs. Boston), Barney sees a woman named Miriam (Rosamund Pike of “An Education”), a friend of a friend, and immediately falls in love. Yes, at his own wedding. He’s not abashed about it, either. He sits across from her, and while she tries to dampen his joy, he smiles a beatific smile. “It really happens,” he says, shaking his head. “Just like that. It’s amazing.”

He follows her onto her train bound for New York, but he’s walletless and ticketless, and married, as she reminds him, so off he goes on his honeymoon to the wrong woman, a woman who, in marriage, between shopping sprees, complains about his friends and cigars and drinking.

The movie handles all this well, by the way. It doesn’t quite stack the deck against her. She’s a pain but sympathetic. He’s charming but an asshole.

Meanwhile, his old friend Boogie, who has written exactly nothing, has become a drug addict, and Barney takes him to his cabin for a weekend of drying out. Instead, Boogie fucks his wife. When Barney finds the two of them together he is 1) shocked, and 2) overwhelmed with joy. He knows it’s his way out.

She blames her infidelity on Barney, of course, while Boogie uses an old line of Barney’s from Italy to justify the peccadillo: “It was the only thing that’d shut her up.” The two old friends then drink, Izzy’s gun is found, and out on the dock, with wildfires in the distance, the gun goes off. When Barney wakes, Boogie isn’t there. The murder he’s accused of committing in the first act goes off in the second.

But the disappearance of Boogie is soon forgotten in lieu of wooing Miriam. They have a disastrous first date in New York—he drinks too much, throws up, passes out—but she’s charmed anyway. They date, get married, have kids, have a life. His father dies, he becomes jealous of a neighbor, Blair, a vegan who’s good with boats and helps Miriam with her radio career, something Barney doesn’t do, and Miriam soon wearies of this, and of Barney’s hockey games and drinking. She leaves him for a week to visit their college-age son in New York and to give themselves some breathing space. Of course, despondent, he sleeps with another woman. Of course she finds out.

“We have life, we have a life,” he pleads.

“We had a life,” she responds.

Brutal.

I never cared for her, to be honest. All Barney’s wives were demanding but she was demanding and removed, not a combination that works for me. He sees something in her, which is why he pursues her, but what does she see in him? A reflection of her ideal self? A woman so dazzling she is pursued by the groom at another woman’s wedding? She acts like she has all the answers, but all her answers are stored inside an icebox that is rarely opened.

“Barney’s Version” is based upon the novel by Mordecai Richler, who also wrote the novel that became “The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz,” and I imagine it sprawling like John Irving’s “The World According to Garp,” which made a great novel but a so-so movie. Same here. The ramshackle life doesn’t quite cohere. The resolution to the Boogie disappearance doesn’t quite resonate, either. We find out, go “Ah,” but that’s about it. The movie does make me want to read Richler, though. A good writer can whip up resonance with words. Filmmakers, poor bastards, are left with just the world.

Saturday September 17, 2011

Movie Review: The Adjustment Bureau (2011)

WARNING: CAN THERE BE SPOILERS WHEN EVERYTHING IS PLANNED?

I can’t get past the timeline.

In “The Adjustment Bureau,” David Norris (Matt Damon), a rising political star, learns there is a team of men—and it is just men—wearing suits and fedoras a la “Mad Men,” and led by a dude named Richardson (John Slattery from, of course, “Mad Men”), who control everything. Or almost everything. They spill coffee, sprain ankles, make sure this person misses that bus and lives; make sure that person crosses this street and dies. The infuriating randomness of life? It’s not random. There’s a plan. For everything and everyone. Feel like you’re stuck in a dead-end job with a dead-end wife? Sorry, that’s the plan. Are you rich and powerful and influential? Do you feel like you’re touched somehow? You are! Greater powers than us are determining your fate! And by greater powers I’m talking ... you know. Upstairs.

“Are you an angel?” David asks Harry Mitchell (Anthony Mackie), who is more or less David’s case officer.

“Are you an angel?” David asks Harry Mitchell (Anthony Mackie), who is more or less David’s case officer.

“We go by many names,” Harry answers.

So if angels are mostly clean-cut, trim men in business suits and hats, and God is called “The Chairman,” what’s the afterlife like? A business meeting? Or is that purgatory?

“The Adjustment Bureau” doesn’t touch on such mundane topics as death, though. It’s more interested in matters of love and free will.

“Whatever happened to free will?” David asks Thompson (Terrence Stamp), the fierce angel/case worker who is brought in on the Norris matter after Richardson and Mitchell fail. David, you see, is supposed to become President of the United States one day, but he keeps deviating from the plan to fall in love with a dancer/choreographer/free spirit named Elise (Emily Blunt).

“We actually tried free will before,” Thompson replies. Then he gives us the following timeline:

“After taking you from hunting and gathering to the height of the Roman Empire we stepped back to see how you'd do on your own. You gave us the Dark Ages for five centuries... until finally we decided we should come back in. The Chairman thought maybe we just needed to do a better job of teaching you how to ride a bike before taking the training wheels off again. So we gave you the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, the Scientific Revolution. For six hundred years we taught you to control your impulses with reason, then in 1910 we stepped back. Within fifty years, you'd brought us World War I, the Depression, Fascism, the Holocaust and capped it off by bringing the entire planet to the brink of destruction in the Cuban Missile Crisis. At that point a decision was taken to step back in again before you did something that even we couldn't fix.”

Height of the Roman Empire. Julius Caesar? Augustus? Were Caligula and Nero part of the plan? Was Jesus? Hey, good news, Christians! Whichever way it turns out with the son of God, Mohammed (570-632) most certainly wasn’t, since he didn’t come around until the decline of the Roman Empire. Take that, Islam!

Plus: For 600 years they taught us to control our impulses? 1310-1910? Right, I forgot. The Great Epoch of Tepidity, marked by continual wars in Europe, the devastation of the native populations in the Americas, and the Marquis de Sade.

But it’s the recent timeline that bugs me. The angels left us alone from 1910 to 1962. So, on our own, we did WWI and WWII and the Stock Market Crash of 1929 from all that greed, which led to the Great Depression. But didn’t we also do, on our own, Gandhi, FDR, the New Deal, the defeat of the Third Reich and fascism, the creation of the U.N., and Martin Luther King and the beginning of the civil rights movement? Not to mention “A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,” “Seven Samurai” and rock ‘n’ roll. Not bad for being abandoned by the angels.

I get ’62, too. Cuban Missile Crisis. World on the brink. But that means the following were all part of the plan: the assassinations of JFK, MLK and RFK; the Vietnam War and Nixon and Watergate; the disappearance of the American middle class. W. and 9/11. Afghanistan and Iraq. The global financial meltdown from all that greed, which led to the Great Recession. Plus take your pick of war, famine, genocide, and Republican president.

Who the fuck is writing this thing anyway?

It gets worse. Since ’62, the movement within the U.S., the most powerful country on earth, has been away from greater social control and toward market forces and anti-regulation and each to his own and que sera sera. And what’s causing all this? The Plan: a form of social control that would make Josef Stalin weep from envy.

Nice message, Hollywood.

Of course that’s not Hollywood’s message. The movie may be about The Plan and our lack of free will, but its ultimate message is the same as it ever was. We do have free will, we can alter the plan, and maybe someday, if we learn to control ourselves, we’ll be writing The Plan ourselves. Rah.

There are bright spots. I liked Norris’ scuffed-shoe speech. I thought Emily Blunt was flirty and fizzy and original, my immediate choice for any future, smart romantic comedy. I wondered if Matt Damon had the flu during filming—he looked a little pig-eyed at times.

The movie is based upon yet another short story by Philip K. Dick, who wrote the stories that became “Blade Runner,” “Total Recall” and “Minority Report,” but whose stories feel vastly overrated to me. They seem silly. Maybe because they remind me of the kind of thing I used to write in my twenties and thirties.

I once wrote a short story called “In God’s Waiting Room," where getting into heaven was like a job interview, which I, or my main character, Ellery Pimentel, kept failing. “The Adjustment Bureau” doesn’t feel much different from that. Here, God is the unseen CEO of a corporation in which we are all lowly members; but if you try hard enough, if you keep persisting, if you kiss the girl at the right moment in the right way, well, you still won’t be able to see Him. But He might, like any good CEO, steal your ideas.

Thursday September 15, 2011

Movie Review: Beginners (2011)

WARNING: IT’S 2011. THIS IS WHAT THE SUN LOOKS LIKE. AND THE STARS. THIS IS THE PRESIDENT. AND THIS IS A WARNING ABOUT SPOILERS.

“Beginners” is a smart, sad, ultimately affirmative film about a depressed, 38-year-old illustrator named Oliver (Ewan McGregor) struggling in a relationship with an actress, Anna (Mélanie Laurent), just a few months after the death of his father, Hal (Christopher Plummer), who, at 75, had revealed to Oliver (and to the world) that he was gay.

It’s also a film that revealed my intolerances. Watching this gay father interact with his depressed son, I realized I have a problem with the depressed.

I have a particular problem with the indie-movie depressed. You look like Ewan McGregor, you have the talent that Oliver has—enough, apparently, to make a living—and you wind up in a relationship with someone who looks like Mélanie Laurent? Give us a smile already. Be like your father: be gay.

I have a particular problem with the indie-movie depressed. You look like Ewan McGregor, you have the talent that Oliver has—enough, apparently, to make a living—and you wind up in a relationship with someone who looks like Mélanie Laurent? Give us a smile already. Be like your father: be gay.

Hal came out a few months after the death of the mother, Georgia (Mary Page Keller), a woman he’d been married to 44 years, and who, during her battle with cancer, ate nothing but French toast, watched Teletubbies, and “skipped back and forth in time,” according to Oliver in an early voiceover.

The film does this, too. We keep skipping between Oliver’s last years with his father and his first months with Anna. The former works beautifully. The latter? Eh.

How sad is that? You put two good-looking people together, you make them artistic, actress and illustrator, and the result is stifling. Here they are at her place. Here they are at his place. Here they are at in the stacks of an old bookstore. Can someone open a window already?

They begin well. After the death of his father, which plunges him into a depression he was always skirting the edges of, his friends drag him to a costume party, and he goes as Sigmund Freud. Good joke. There, he drinks and mock-analyzes another partygoer on the couch. Then Anna takes this partygoer’s place, dressed as I’m-not-quite-sure, and writing notes rather than talking. Apparently she has laryngitis. As her character or as herself? She kinda flirts with him and he kinda flirts back. We never know what initially attracts her—he’s a fairly quiet guy in heavy beard and gray hair, after all—but later in the evening he removes the beard and looks like Ewan McGregor. So: Jackpot.

What do they do together as a couple? I hardly remember. After the party, in his car, he says he’ll go where she points, and they wind up driving on a sidewalk and laughing. This scene is reiterated later in the movie, but previously in his life, when he was a child and his mother told him she’d drive where he pointed. The movie does this a few times. We get a sense of how past relationships, particularly with our parents, inform present life. The past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past, as Faulkner said.

But then it’s old bedrooms and old bookstores for these two. He’s passive, she barely talks. The laryngitis was hers. There’s something almost silent-film comedienne about Anna, intentional, I assume, but it plays like an affectation rather than a means to knowledge or insight. Their relationship is mostly silence and a kind of silent dread over ... the past? The inevitable breakup they see coming? They each seem to be holding their breath, out of love, or out of being stifled by love, and part of it feels real but it’s never particularly interesting. I guess I’m a snob of dialogue. I wanted them to say something.

Hal does. Hal, finally himself after 75 years of lies, lives. He’s part of a community now, and there are movie nights and Los Angeles Pride meetings and fireworks. He meets young men, who aren’t interested in him, in clubs; but then one is, Andy (Goran Visnjic), who seems odd with his outré behavior and Javier-Bardem-in-“No-Country-for-Old-Men” haircut, and for his fixation with those old men, for whom this country is no country. But he’s deeper and more forthright than we imagine. He comes through in the end. He reveals himself to be meaningful.

Oliver watches it all. He’s a good watcher. Many of us are. But we need something worthwhile to watch: Hal living, Hal dying, Hal hiding from Andy and his friends that he’s dying. Christopher Plummer is amazing here, an early lead in the best supporting actor race. The details of Hal's slow walk toward death are evocative. Here’s Oliver organizing Hal’s pills for him. Here he is shaving him. Now hospice is called. Here’s the bed in the middle of the living room. Here’s Hal finally allowed to be himself for a few shining moments.

Anna is lovely to watch but we never get a sense of who she is, and who she and Oliver are.

No shock, by the way, that writer-director Mike Mills based the father-son relationship on his own relationship with his father, who, yes, came out at 75 after the death of the mother, then died of cancer. Was there no woman, no girlfriend, no f-buddy that Mills could base Anna on?

There’s a dog, too, a Jack Russell terrier named Arthur, who is given subtitled dialogue, and who seems to talk more than Anna does; and we’re given history lessons about Jack Russell terriers and the history of the homosexual movement in America, and it’s done with a kind of Wes Anderson deadpan, a kind of camera-center formality that worked.

Most of “Beginners” worked, really. I feel dickish for even raising criticisms, but they're imbedded within the film itself.

Oliver to Arthur, the dog: “Look, it’s lonely out here, so you better learn how to talk with me.” Back atcha, buddy.

Hal to Oliver, the son: “Just be happy about it, huh?” Amen.

Thursday September 08, 2011

Movie Review: Crime D'amour (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS THAT TRADE SUSPENSE FOR MYSTERY

Google “Hitchcockian thriller” and you’ll get more than 68,000 results, including such recent films as “Unknown,” “Source Code,” “With Friends Like Harry,” and, yes, “Crime d’amour,” starring Kristin Scott Thomas as Christine, the boss from hell, and Ludvine Sagnier as Isabelle, her sometimes flustered protégé.

What’s Hitchcockian about it? Ten minutes into the movie, we get this scene. Christine and Isabelle are about to leave Paris for Cairo on a business trip when Christine—with a better offer, an apparent weekend fling—decides to send Isabelle alone. She offers this advice: “You should do something with your hair. Let’s see it down.”

Isabelle, blonde and pretty, obliges. For a moment, a belittling amusement shines in Christine’s eyes. Then she shrugs.

Isabelle, blonde and pretty, obliges. For a moment, a belittling amusement shines in Christine’s eyes. Then she shrugs.

“Keep it up,” she says, dismissing her and going back to work.

Alfred Hitchcock, lover of pretty blondes with their hair in a chignon, would surely agree.

But that’s about as Hitchcockian as we get.

Yes, there’s a crime, and the wrong person is accused. But Hitchcock was a pungent filmmaker. He loved the horrific reveal, the discordant clang on the soundtrack. He wanted to push our faces in it. “Crime d’amour,” in comparison, is distant. The film itself is an icy cool blonde.

(More on Hitchcock later.)

The movie begins with a late-night brainstorming session between Christine and Isabelle at Christine’s mansion. Ideas are tossed out and Christine flirts with her subordinate in a way that flirts with illegality—at least under U.S. law. She comes up close to her. She tells her she smells good. She gives her a scarf. Then her lover, Philippe (Patrick Mille), shows up, and Isabelle, flustered, possibly hot-and-bothered, is told to leave by the back door.

Christine is hardly the perfect boss. When the Cairo meeting goes well because of an innovation from Isabelle, Christine takes credit—in front of Isabelle. But when Isabelle, spurred on by her subordinate, Daniel (Guillaume Marquet), hides her latest idea from Christine—an idea that will raise company value by 20 percent—she gets sole credit, and the D.C. mucky-mucks, suspecting Christine’s subterfuge, delay her promotion to New York. Thus begins Christine’s revenge. She uses Philippe, with whom Isabelle became intimate in Cairo, to set up and stand up Isabelle, then films Isabelle’s emotional response and shows it during an office party “pour rire,” she says. For a laugh. From Isabelle’s computer, she sends herself a threatening note, then threatens to use it, this fictitious threat, against the younger woman if she doesn’t fall in line.

Isabelle’s reaction? She slits Christine’s throat.

On one level, I was disappointed. Really? No more Christine? That’s as bad as the boss-from-hell gets?

On another level, I was amused. Christine is busy playing feminine cat-and-mouse games, attempting to destroy her rival’s spirit bit by bit, and Isabelle’s response is as male as it gets. Nothing “bit by bit” about it.

Finally, I was intrigued—at least initially. In the aftermath of the killing, which was sudden and clean, Isabelle incriminates herself. She cuts off a bit of a scarf Christine gave her and puts it in Christine’s right hand. Then she takes Christine’s left hand, dips it in the blood that’s been pooling on the floor, and uses it to write out “I-S-A...” Then she goes home, calls in sick for the day, and waits for the police. When they arrive, she acts dazed. At the police station, they confront her with the threatening email, and, still dazed, she confesses. Off to prison.

All the while we’re wondering: What is she up to? More, what is writer-director Alain Corneau up to? Why does he reveal her culpability so early? Why not delay the murder scene, give us calling in sick and being hauled downtown and prison, so we’ll assume Isabelle is falsely accused? So we may even assume Christine masterminded the whole thing? Why give up all that?

Back to Hitchcock for a moment. One of the initial criticisms of “Vertigo,” which is now considered one of the greatest movies ever made, was how the filmmaker revealed the backstory of Judy Barton (Kim Novak) to us before Scotty (James Stewart) could figure it out. Some critics complained that, in doing so, Hitchcock sacrificed mystery for suspense, but Hitchcock was always willing to do this. He was always about suspense before mystery. He wanted us on the edge of our seats.

Corneau’s big reveal does the opposite. He sacrifices the suspense of the wrongly accused for the mystery of “What is she up to?” Our uncertainty for the rest of the movie isn’t anxious or excited, as with Hitchcock; it’s intellectual. We’re not on the edge of our seats. We’re leaning back, wondering. In this way, “Crime d’amour” isn’t Hitchcockian at all; it’s anti-Hitchcockian.

Surely, I wondered, Corneau has a good reason for letting the air out of the movie. Surely Isabelle has some kind of master plan that will make us all go, “Ahhh!”

She does, but it makes us go, “Eh.”

Isabelle sets herself up only to free herself, as a way of getting past the incriminating email threat. She knew she would be a suspect so she made herself one, then planted the evidence that would set herself free and imprison Philippe. Afterwards, she is welcomed back at the company, gets Christine’s office, and continues on her upward business trajectory.

But so what? She kills Christine without Christine knowing it. Is that revenge? Plus she tarnishes her own name in the process. Was there no better way?

Then there’s the mystery of the title: “Love Crime.” Isabelle’s love for Christine, one assumes. Philippe is an afterthought here. He’s a plaything between two cats—one a housecat, the other a lion. But that makes the crime even more incomprehensible. Doesn’t all the fun go out for Isabelle after Christine is extinguished? Doesn’t she need Christine there to witness her triumph? She’s able to increase a company’s worth by 20 percent in her spare time but can’t she come up with a better revenge plot than this?

Cue Hitchcock. Harrumph.

Monday August 29, 2011

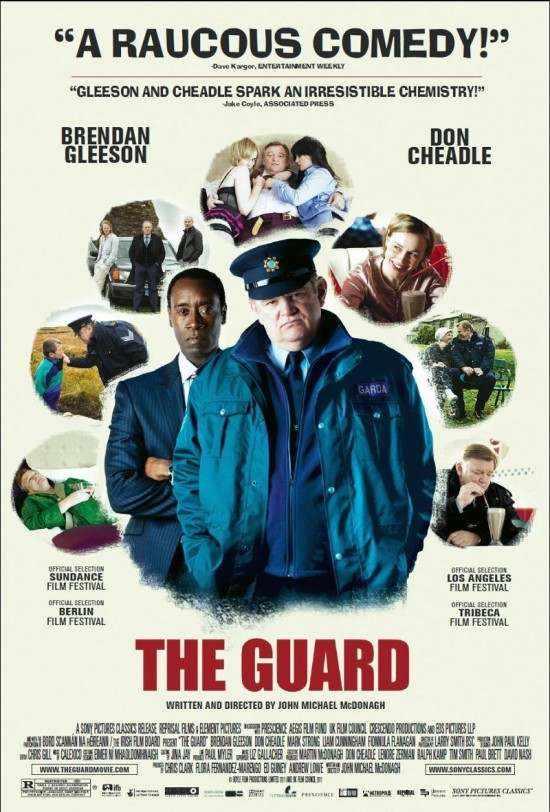

Movie Review: The Guard (2011)

WARNIN’: SPYLERS

FBI agent Wendell Everett (Don Cheadle) says the key line about the protagonist in “The Guard,” Sgt. Gerry Boyle (Brendan Gleeson), a third of the way through the film. He says, “You know, I can’t tell if you’re really motherfucking dumb or really motherfucking smart.”

We’ve been wondering the same thing. Veering toward the latter.

Boyle is a cop, or garda, in a small town in Connemara in the west of Ireland. The movie opens with kids drinking and driving and taking drugs and speeding. Then they shoot past a police car parked by the side of the road. Then there’s a crash. Only then does the police officer (Boyle) react. He sighs and rolls his eyes.

Boyle is a cop, or garda, in a small town in Connemara in the west of Ireland. The movie opens with kids drinking and driving and taking drugs and speeding. Then they shoot past a police car parked by the side of the road. Then there’s a crash. Only then does the police officer (Boyle) react. He sighs and rolls his eyes.

Boyle is a man who doesn’t want to do much because there’s no point in it; the world is the way the world is.

But he’s given a new partner, Aidan McBride (Rory Keenan), fresh out of Dublin and gung ho. The two come across a dead body, an actual dead body, under creepy circumstances: bullet in the forehead, Bible verses stuffed in his mouth, potted flower in his lap, the number 5 1/2 on the wall. A serial killer? But why the number 5 1/2? “There was a movie ‘8 1/2,” McBride states. “Fellini.” Pause. “There was a movie ‘Se7en,’” he adds.

“You gonna list every fookin’ movie you can think of with a number in it?” Boyle asks.

At the police station we see Boyle taking notes. Nope, he’s actually drawing nonsensically. When a straight-arrow FBI agent, Everett, arrives and speaks to the local police force about an impending shipment of cocaine with a street value of $500 million, Doyle raises his hand and asks which street. Because doesn’t the value differ from street to street? (That’s the motherfucking smart part.) He adds that he thought all drug dealers were black lads. Or Mexicans. (That’s the motherfucking dumb part.) Accused of racism, he pleads multiculturalism: “I’m Irish. Racism is part of my culture.” He also knows something they don’t: One of the four men they’re looking for is dead; the guy with the bullet in his forehead and the number 5 1/2 on the wall.

“The Guard,” written and directed by John Michael McDonagh, is like its protagonist: dry and humorous. The three remaining drug dealers and killers, played by Liam Cunningham, David Wilmot and Mark Strong, have conversations like British variations of Tarantino’s criminals: they quote Nietzsche, argue whether “sociopath” or “psychopath” is worse, and make criminality seem like your own job by lamenting: “I’m just sick and tired of the people you have to deal with in this industry.” Whenever any local hears that Boyle is working with a man from the FBI, they ask, “Behavioral Science Unit?” Boyle takes his mother (Fionnula Flanagan), dying of cancer, to a nightclub so she can hear live music again, and when she laments missing out on life, he tells her, with his usual straightforwardness, “Sure you missed out, generally. You’re not fookin’ alone, dear.” The psychopath (Wilmot), dying, has the same lament.

But there’s silliness here as well. When Boyle refuses to work on his day off—instead indulging in a three-way with two prostitutes who are as pretty as actresses, because, of course, they are—Everett, rather than getting assistance from another cop, drives around the county by himself trying to extract information from the tight-lipped Irish, who don’t even speak English. That’s really motherfucking dumb. Later, he buys into disinformation about the drug dealers, dismisses a call from Boyle with the comment, “Idiot,” but still shows up, a la Han Solo and countless action movies, to be Boyle’s second for the gun-battle finale. That’s really motherfucking conventional.

The film is a little too in love with Boyle, too. It makes him always right and the straight-laced always wrong. It doesn't linger enough on the possibility that he's really motherfucking dumb.

And could a brother get some subtitles? It’s in English, sure, but I only understood about two-thirds of it. The other third, thickly Irish, was lost on my thick American ears.

The question many viewers will have at the end of the movie, I assume—a question that might even have brought you to here via the search engine of your choice—is whether Boyle survives the fire aboard the cocaine-laden ship. Does Boyle live? you ask. Of course he does. He’s forced into the final gun battle because the bad guys couldn’t let him be. But he also knows, as the ostensible gang leader, Francis Sheehy (Cunningham) tells him, “There are men behind the men.” So taking care of these guys won’t finish the problem. More will come at him. Unless they think he’s dead. That’s the conclusion Everett comes to at the end anyway. He replays the key line about Boyle, quoted at the beginning of this review, holds on Boyle’s smiling face, and then the soundtrack gives us the old John Denver song, “Leavin’ on a Jet Plane.” Which is where Boyle went. Which is why Everett smiles.

Boyle, in case we didn’t know it by now, is really motherfookin’ smart.

Tuesday August 23, 2011

Movie Review: Unknown (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

“Unknown” is mostly dumb. It begins in the wrong place, telegraphs its big reveal, then gives us one of the worst lines in movies to justify the plot after the reveal. It might’ve been a smart thriller in the 1970s but our age needs to feel uplifted. We’re too cowardly and depressed to want anything but heroic and happy.

Liam Neeson plays Dr. Martin Harris, an American professor visiting a bio-tech conference in Berlin with his beautiful wife, Liz (January Jones). We see them on the airplane, going through customs, arriving at their swanky hotel. But the cabdriver missed Martin’s briefcase at the airport so he hails another cab and goes back. Good luck: The cab driver is the best-looking cab driver in the world, Gina, played by Diane Kruger. Bad luck: there’s a multicar accident, they go over a bridge and into the icy water below. He’s banged up and in a coma for four days. She disappears after saving him.

When he recovers, he’s a John Doe in the hospital. Nobody knows who he is.

When he recovers, he’s a John Doe in the hospital. Nobody knows who he is.

He assumes his wife is distraught so he rushes out of the hospital and back to the swanky hotel, where the dignitaries are in the middle of a conference. From afar, he sees his wife in a nice backless dress, but she has no idea who he is. Moreover, there’s another Dr. Martin Harris, played by Aidan Quinn, and this guy has all the right credentials. Our Martin Harris has no credentials.

For the next 20 minutes of screen time, our Martin Harris fights, then acquiesces to, his loss of identity. His university website includes a picture of the other Martin Harris. The other Martin Harris knows the details, the same details, down to the same words, of his relationship with Liz, and how, over the phone and via email, he described that relationship to Prof. Leo Bressler (Sebastian Koch of “The Lives of Others”), the man hosting the bio-tech conference, who has, unfortunately, never seen him. Our Martin Harris moons outside of restaurants, where his beautiful wife dines with the other guy. He begins to doubt his own mind.

Three thoughts at this point:

- No Skype for these scientists?

- The movie really should’ve begun at the accident site, or at the hospital, so we could doubt his mind with him. But we saw him arrive in Berlin with Liz. We know he’s the real Martin Harris. We’re just wondering how and why this is happening.

- You could argue his tragedy at this point is less the loss of his identity than the loss of his wife. He’s been cuckolded in plain sight. It helps that she’s young and beautiful. Imagine him mooning outside a restaurant where some fat cow gorged herself. You’d have a whole other movie. Maybe a better one.

After attempts are made on his life, he snaps out of it and quickly assembles a kind of crew: Ernst Jürgen (Bruno Ganz of “Wings of Desire” and “Downfall”), a former Stasi official, who’s an expert at finding missing people; and Gina, the cab driver, an illegal immigrant (Kruger, German, plays Bosnian), who eventually confirms he is who he thinks he is. She also lets him come back to her place for a shower. Nice lady. Nice cabdriver. Cue Prince:

Lady cab driver — Can U take me 4 a ride?

Don't know where I'm goin' 'cuz I don't know where I've been

Kidding. No Prince here. No sex, either. Just gun fights and car chases and New Order.

Jürgen, a secondary character, steals the movie. He’s proud of his immoral past and good at what he does. And he quickly figures out the obvious. One of the guests at the bio-tech conference, Prince Shada (Mido Hamada), is a progressive Arab who has already survived one assassination attempt. Jürgen assumes the new Martin Harris is an assassin to take out Prince Shada. Section 15, a legendary assassination unit, is mentioned. Then Rodney Cole (Frank Langella), shows up in Berlin, claiming several phone calls from Martin, and he visits Jürgen, who figures out Cole is the leader of Section 15. They have a tête-à-tête, maybe the best scene in the movie, before Jürgen kills himself like a good soldier.

By this point, if you’ve been paying attention, you’ll add up the following:

- When Martin first arrives in Berlin and is asked the purpose of his visit, he responds, “I’m here to give a lecture at a bio-tech conference.” Liz teases him about it in a way that could be wifely but could be more.

- When he first wakes up in the hospital, the doctor asks him no long-term memory questions.

- His memories of Liz include a recurring scene in which she has dark hair and says, “Are you ready?”

Jürgen, dying, provides the giveaway. He says to Cole, “What if he remembers everything?”

He’s the assassin. Our Martin. He went into a coma and when he woke up he only remembered the cover, he didn’t remember his true identity.

A bummer they telegraphed it—I would’ve removed the “Are you ready?” scenes—but also an opportunity. All this time, we’ve basically been rooting for a guy who turns out to be the villain. What happens now? Do we get flashbacks to all the people he’s killed? Maybe his memory is fully restored, and in that restoration his true personality emerges, and he has to kill Gina who knows too much? Can they make us horrified that we once cared about him? Can they do something darkly 1970s and Alan J. Pakula-ish?

Not even close. Instead, he and Gina have a heart-to-heart. When they were first set upon by German assassins, she slapped his face, saying angrily (and historically inaccurately), “My family in Bosnia was killed by people like that!” Now he’s a person like that. So what does she do?

She says one of the worst lines in movies this year: “What matters is what you do now, Martin.”

Holy crap, that’s bad. One of the themes of “Unknown” is amnesia—both personal and national. “We Germans are experts at forgetting,” Jürgen says upon meeting Martin. “We forgot we were Nazis. Now we have forgotten 40 years of Communism—all gone.” It’s not a positive, this forgetting. But suddenly it is. So that we may have our action-hero ending.

Which we get. The assassin becomes the anti-assassin and foils the plot—which turns out to be more complicated—and beats up the other Martin. Liz, meanwhile, gets blown up through her own incompetence. And in the end, Martin, our Martin, and Gina, his new beautiful blonde, with new names and new fake passports, have a light, whimsical exchange as they prepare to travel:

Gina: [opening her new passport] Claudia Marie Taylor. I like it.

Harris: It suits you.

Gina: Who are you?

Harris: Henry. Henry Taylor.

Gina: Nice to meet you, Mr. Taylor.

Harris: Nice to meet you...

Where are they going? Unknown. What is our protagonist’s real name and real past and real personality? Unknown. What is our capacity for absorbing bullshit like this? Unknown.

What matters is what you do now, Hollywood.

Tuesday August 16, 2011

Movie Review: The Tree of Life (2011)

WARNING: NATURAL (RARELY GRACEFUL) SPOILERS

Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life,” which is confusing audiences around the world, is essentially an unresolved Oedipal tale in 1950s Waco, Tex., punctuated by frequent Job-like prayers to God, and framed by the beginning and end of time. What’s so difficult to understand?

Of course, for “unresolved Oedipal tale” you could substitute a boy’s internal struggle between the way of nature, which is the way of his father (Brad Pitt), and the way of grace, which is the way of his mother (Jessica Chastain). That’s the true battle. The first words we hear, in fact, in voiceover narration from the mother, set up this dichotomy:

The nuns taught us there were two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you'll follow.

These lines are also in the trailer and I loved them as soon as I heard them.  She sets up the dichotomy, gives us one half, nature, and in the audience I thought, “OK, so what’s the negative half?” I’m so used to nature, juxtaposed with the cruddier aspects of modern society, being used as the positive, as the “what we need to return to,” that I assumed the same here. But in the larger scheme of things, which is the only scheme Malick works in, nature is what we are while grace is what we aspire to be.

She sets up the dichotomy, gives us one half, nature, and in the audience I thought, “OK, so what’s the negative half?” I’m so used to nature, juxtaposed with the cruddier aspects of modern society, being used as the positive, as the “what we need to return to,” that I assumed the same here. But in the larger scheme of things, which is the only scheme Malick works in, nature is what we are while grace is what we aspire to be.

Again, from the mother:

Grace doesn't try to please itself. Accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked. Accepts insults and injuries.

Nature only wants to please itself. Gets others to please it, too. Likes to lord it over them. To have its own way. It finds reasons to be unhappy when all the world is shining around it. And love is smiling through all things.

Malick’s voice-over narration, used extensively in his films, never feels like voice-over narration to me; it’s more an articulation of our most profound feelings. It’s poetry.

The movie’s epigraph is from the Book of Job—another piece of poetry:

Where were you when I laid the foundation of the earth? Tell me, if you have understanding. Who determined its measurements—surely you know. Or who stretched the line upon it? On what were its bases sunk, or who laid its cornerstone, when the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?

This is essentially the “Who are you to question Me?” Bible verse and it’s invoked throughout the film, since God is questioned throughout the film, particularly around the issue of death. A boy dies at a neighborhood swimming pool and young Jack (Hunter McCracken), our protagonist for much of the movie, who is trying to sort through everything, and who has already prayed to God to help him be good, asks, “Where were You? You let a boy die.”

More immediately, there is the death of Jack’s younger brother, R.L. (Laramie Eppler) which opens the film, but whose death appears to be set 10 years after the film’s centerpiece. A telegram arrives—one assume a war—and the mother receives it, reads it, sits back stunned, horrified, and then a strangled scream begins to emit from her throat when we cut to the father at the noisy airfield where he works. The way this is directed by Malick and edited by his team of five—not to mention the acting and the sound effects editing—is brilliant. And it eventually leads to this thought, again from the mother, in voiceover: “Lord: Why? Where were you?”

At which point, as if in answer, we cut to the beginning of time.

Some have mocked Malick for his deep perspective, and for showing us the creation of life, both in the universe and on earth, and the movement of life on earth from water to land, but it is the ultimate answer to her and his and our question. Where was God when tragedy struck? That’s what existence is. Life is birth and change and death. He let every dinosaur die and you’re questioning him about R.L.? But that’s the way with us. Only when it hits close to home do we question it. Only when it happens to the good do we question it. Only when it hurts beyond measure. But the argument can be made, and has been made, millennia ago, that it’s the hurt that moves us from the way of nature to the way of grace. Aeschylus:

In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.

Young Jack’s battle is more immediate. We see him from birth to ... age 10? 12? We see him run and strive and pause and figure out. Malick tells his tale unconventionally, through images and metaphor and music. We go from a door opening underwater to the birth to the small foot in the big hand. We go to the ball, and walking with daddy, and running, and iodine on the cut knee. We go to the mother with the butterfly and the animal blocks: the Alligator; the Kangaroo. Jump jump jump. Then we go to the crib by the window and the new baby brother and the look on the boy’s face like “What the hell?”

This is a period dominated by the mother. Malick’s images are so evocative they reminded me of my own, two decades and 2,000 miles further north: frogs and grasshoppers and Halloween; climbing trees and kick-the-can and sparklers; running through yards and rolling down hills. There was a fire—God let that happen, too—from which a neighborhood kid still has the burn marks on the back of his head, where no hair will grow, and it freaks Jack out, this imperfection, and he keeps his distance. It also reminded me of a kid I used to see playing in the Lynnhurst swimming pool in Minneapolis in the late 1960s. He was a burn victim, too, with burns on his back and chest, and it freaked me out, this imperfection, and I kept my distance.

There’s also, amidst all this, the learning of boundaries—the neighbor’s yard, don’t cross this line—lessons imparted by the father. The idyllic period, the mother period, comes to a close, you could say, at the dinner table, when young Jack asks, “Pass the butter, please,” and Jack’s father corrects him, “Pass the butter, please, sir,” then stands up to imaginarily conduct the Brahms they’re listening to.

Now it’s the father who dominates. He’s not a bad man, or a bad father, he’s just the way of nature. He’s trying to teach his boys how to be tough in a tough world. He doesn’t want them to wind up like him, who gave up his calling, music, for regular work, to which he goes to regularly, never missing a day, and comes home dissatisfied and unwanted. He wants his boys to grow but stunts them. At the dinner table, young Jack seems almost deformed, hunched over and twitching, since he doesn’t know what he’s allowed to do, since the boundaries the father is imposing are both necessary and seemingly arbitrary, not to mention hypocritical. Elbows off the table. Yet his father keeps his elbows on the table. In the yard, when the father affectionately tries to rub the back of his son’s neck, Jack flinches.

The mother is soft, the father hard. The mother points to the sky and says “That’s where God lives” and the father says “Hit me.” He says, “It takes fierce will to get ahead in this world.” The mother is good, and the boy wants to be like her, and he prays to God to be like her, and the father says, “You want to succeed, you can’t be too good.”

It’s the younger brother, L.T., who rebels first, at the dinner table, telling the father to be quiet, and there’s an eruption, and everyone scatters, and the father is left alone shoveling food into his mouth. At the same time, L.T. is closer to the way of grace. He has the best part of the father, his musical talent, and there’s a scene where he plays guitar on the front steps, and the father listens, proud, that his son has an ear, while Jack stalks the edges and plots. As the father dominates Jack, Jack tries to dominate his brother. But L.T. says, “I won’t fight you.” L.T. says, “I trust you.” L.T. paints beautifully and Jack upends water on the painting. As Jack’s relationship with his parents give off whiff of Oedipus, so his relationship with his brother gives off whiffs of Cain.

The entire movie is a montage, impressionistic, one image leading to another, things all of a sudden just happening as they do in the world of kids. They wake up one morning and their father is gone— on a business trip, apparently; around the world, it turns out—and Jack, freed from under his father, becomes more like his father. He becomes more like the way of nature. He and his friends stalk the neighborhood, like extras out of “Lord of the Flies,” throwing rocks at the windows of abandoned garages. Jack has discovered girls at school and now he discovers women in his neighborhood, including his mother, washing her bare feet with the hose. One day he sees a neighbor lady leaving her home and he sneaks inside and looks through her things. He lies her nightgown on the bed. Then he’s running with it, breathlessly, down to the creek, where he hides it, his shame and his desire, under a log. But that’s not good enough. People are passing. So he puts it in the creek and lets the current take it away. Again, I was reminded of my youth, and the perverse way a burgeoning sexuality exhibits itself.

When the father returns, excited by his trips to China and Germany, things get worse. It’s a clash of the ways of nature. Jack sees his father flirting with a waitress, keeping the dollar bill just out of her grasp, and it’s like an earlier scene at school, where Jack had done the same with a pretty girl correcting his paper. He sees his father working under his jacked-up car, and he knows how easy it would be to kick the jack away. He actually looks around to see if anyone is watching. Even his prayers are now the way of nature: “Please, God, kill him. Let him die.” Then his father’s plant closes and his father returns diminished and the family is forced to move. The father calls Jack his sweet boy but Jack says, “I’m as bad as you are. I’m more like you than her.”

This is the brunt of the movie, as I said, with excursions to the beginning of time and into contemporary times, with an adult Jack (Sean Penn), a successful architect, still dealing with the legacy of his father and the death of his brother. We see him lighting a candle to his brother. We see him apologizing by phone to his father. We see him waking up and not talking with his wife. They live in a vertical box of glass and stainless steel and he works in a bigger vertical box of glass and steel, and he designs same, one assumes, and for a time I thought this was a third way, since neither grace or nature is present, but I don’t think that’s where Malick is going. I’m not quite sure where he’s going, to be honest. We get images, dream images, which may be of heaven, or the end of time, or death. When Jack was born he floated through an underwater door and here he walks through a door in the desert so death can be assumed. He winds up on the beach—that point where life began—and we get reunion and reconciliation and forgiveness: the adult Jack with his father and mother; with the young L.T. and with his younger self. We get a sense of welcome and forgiveness and grace. Then we see the adult Jack, back in his office, smiling. We see a skyscraper of glass and steel and all that represents. We see a long extension bridge and all that represents. We see the flickering flame image we’ve seen throughout the movie. Is it God? Is it akin to Kubrick’s monolith? Whatever it is, it’s the last image we see in the movie.

So. The obvious question: What does this unremarkable Waco, Texas family have to do with the beginning and end of time? The obvious answer: as much as anyone.

Another obvious question: How much of the Waco period is Malick’s own childhood? It feels very memoirish. One can even imagine the movie simply being the Waco period, with more conventional voiceover narration (from the adult Jack) and more conventional scene presentation. But that would not be a Malick movie; and it would be a lesser movie.

There are few movies as ambitious and beautiful as “The Tree of Life.” It doesn’t all work for me, but, where it does work, it works on a level few works of art, let alone movies, reach.

Friday August 12, 2011

Movie Review: The Rise of the Planet of the Apes (2011)

WARNING: GO-GO GORILLA SPOILERS

We want the apes to win, don’t we? I didn’t realize that going in. We root for underdogs in movies and the original series began with apes in control and Charlton Heston mute (finally mute), so we root for the humans there. It’s not until the fourth in the series, “Conquest of the Planet of the Apes,” with Roddy McDowell as Ceasar, son of Cornelius and Zira, the chimp couple who arrived from the future (for more sequels), that we finally get our ape on.

“Rise” is basically “Conquest,” so I should’ve realized where our sympathies would lie. But it goes beyond rooting for the underdog, doesn’t it? We arrive at the theater after another crappy day at the office, if we have an office to go to, and the news is all about the stock market dropping because of the debt in Europe, or the debt in America, or the S&P’s downgrade of the U.S.’s credit rating, with both political parties in the U.S., particularly the uncompromising one (you know), pointing fingers and chattering and pounding their chests, so you’re disgusted to begin with; then in the row in front of you, two slobs, slouched in their seats, knees up against the row in front of them, talk through the trailers and through the beginning of the movie and into the movie, and you think, “Really? You’re going to keep this up? You have so little regard for the rest of us, douchebags, that you treat this theater like it’s your own home entertainment system?”; and all of that just to watch, up on the screen, 30 feet high, pretty boy James Franco playing Will Rodman, supersmart scientist, and former supermodel Freida Pinto—one of the prettiest girls in the world—playing Caroline Aranha, just your run-of-the-mill zoo veterinarian who needs a date, and they’re such lies it makes you want to kick somebody, particularly the two louts who keep talking in front of you, and who force you, halfway through the movie, to change seats, as, on the screen, the apes, the intelligent apes, race through and tear up an office like the office you work in, and a traffic jam like the one you were stuck in, and a zoo full of more dolts and douchebags, full of the slackjawed, popcorn-munching endgame of humanity, and you think, “Yeah, that’s it, end it, wipe it all away. We don’t deserve it anymore. We’ve created crap. C’mon, monkeys, lay it all to fucking waste.”

Or am I projecting?

“Rise” is smarter than “Conquest.” It’s “Conquest” injected with ALZ-112, the serum Dr. Rodman tests on monkeys to better treat Alzheimer’s patients like his father, Charles (John Lithgow).

“Rise” is smarter than “Conquest.” It’s “Conquest” injected with ALZ-112, the serum Dr. Rodman tests on monkeys to better treat Alzheimer’s patients like his father, Charles (John Lithgow).

The movie begins (and ends) in the jungle, as locals flush the monkeys and capture a few, including a smart female chimpanzee who becomes the focus of Dr. Rodman’s experiments. The drug not only makes her smarter, way smarter, it gives the irises of her eyes flecks of green, so she’s dubbed Bright Eyes—just as Zira in the original “Planet of the Apes” dubbed Charlton Heston’s character “Bright Eyes.” This monkey is about the be put on display before the money (not monkey) people when she gets aggressive, attacks her handlers, busts into the cafeteria, into the lobby, then crashes through the window where the money (not monkey) conference is being held. She’s shot to death by an alert guard. And there goes the ALZ-112 funding.

But guess what? Dr. Rodman discovers Bright Eyes wasn’t being aggressive. She’d been pregnant the whole time! And she’d just had her baby! So she was protecting her baby like any mother would!

So shouldn’t Rodman tell his overbearing boss, Steven Jacobs (David Oyelowo, British and therefore evil), about the baby chimp and save his ALZ-112 project? Or would he then have to admit that he’d had this chimp in his lab for months, testing it every day, and didn’t even know she was pregnant? Tough call.

The baby chimp, a male, also has flecks of green in his irises—ALZ-112 gets passed along, apparently—so Rodman does what any pretty-boy scientist would do when chimps all around him are losing their lives: He brings this one home and raises it like a son. And it is like a son. We watch the chimp, dubbed “Caesar,” grow from sweet boy to mischievous child to moody teen. We watch him watch the world from a round attic window and occasionally get into the action, which inevitably causes problems with Rodman’s rude neighbor Hunsiker (David Hewlett). As he figures out his place, he has questions, which he signs to Rodman. “Am I a pet?” “Where are my mother and father?” Rodman drives him to the lab and tells him the tale. It doesn’t sit well.

Rodman also tests ALZ-112 on his father, who is cured—temporarily, it turns out—but at least he gets his life back for several years. Amazing breakthrough. And who does Rodman tell? Jacobs? The press? The world? Nope. He tells no one. Because that’s not the story here.

The story here is how Caesar, from his attic window, sees the father, Charles, being attacked, or at least manhandled, by the rude neighbor, so Caesar attacks back with frightening rapidity, strength and smarts. He winds up in an animal control shelter, which seems nice, but it’s run by John Landon, played Brian Cox, who experimented on mutants in “X-Men 2,” and his son, Dodge, played by Tom Felton, who played Draco Malfoy in all the “Harry Potter” movies (poor bastard), so you know it’s going to be a hellhole. Which it is. The other monkeys there don’t help. Caesar tries to make friends but has his shirt torn off by the dominant monkey. A firehose is used on him by Malfoy. He pines in his cell and finds a piece of chalk and draws his old attic window on the wall and leans against it. (A very effective moment, actually.) Then he gets angry and begins to plot.

First he becomes the dominant monkey in the yard. Then he realizes he needs smarter companions, smarter apes (welcome to the party, pal), so he escapes, brings back canisters of ALZ-112, and rolls them through the monkey cages. When Malfoy wakes up the monkeys the next morning, there’s very little of the usual chatter. They’re all startlingly calm. They’ve woken up.

The turnabout at the animal shelter is the best scene in the movie and contains many an homage to the original series—including Charlton Heston, as Moses, on a nearby TV, and Malfoy shouting at Caesar “Get your stinkin’ paws off me you damned, dirty ape!”—but it’s more a “2001” moment than anything. Caesar takes the rod-like taser from Malfoy and raises it high in the air like the club in Kubrick's “2001: A Space Odyssey.” The evolutionary moment has arrived. We’re only missing Richard Strauss’ “Also Sprach Zarathustra.”

There’s an epic battle on the Golden Gate Bridge, which Caesar sees as the path to the redwood forests of northern California, which is where he wants to be. The bad guys get theirs, a few good monkeys die, and when Dr. Rodman shows up in the Redwoods and tells Caesar, “C’mon, let’s go home,” Caesar, who first spoke with one of the most powerful words in the English language, “No!,” whispers in his former owner/master/father’s ear, “Caesar is home”; then he climbs a tree and imperiously looks out over his domain. Caesar is also smart enough to know, as Dr. Rodman apparently is not, that there is no home anymore; that if they go there, they’ll find the cops and the U.S. Army and the entire international press corps waiting for them. You did WHAT? You made him into WHAT?

Despite my complaints, which include James Franco’s new “nothing” method of acting, “The Rise of the Planet of the Apes” isn't a bad summer flick. As for what the apes can tear through and upend in “Apes II”? Here are a few suggestions: 1) the FOX-News studio, 2) a meeting of the Texas Board of Education, 3) a Michele Bachmann and/or Sarah Palin and/or Rick Perry event; 4) the Mall of America; and 5) a couple of douchebags, slouched in their seats, talking through a movie. With humans, really, the possibilities are endless.

Wednesday August 10, 2011

Movie Review: Sarah's Key (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS IN THE CLOSET

“Sarah’s Key” is half of a great movie.

The first hour details the horrors of holocaust better than recent films such as “City of Life and Death” and “John Rabe,” both about the Rape of Nanjing, or “Le rafle,” a French film about the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup of Jews by the occupied French, and for the Nazis, in 1942. Those films tend toward melodrama. Here’s what I wrote about “Le rafle.”:

What is it with these recent movies about the horrors of World War II anyway? Why do we need to milk tragedy this way? Why is it not enough that Jewish mothers and children are stuffed into cattle cars bound for Poland? Do we need to intercut to the sympathetic, feverish nurse, biking to the train station on her last legs, on the hope that ... what? What if she got there in time? What could she do? Who would she stop? The French police? The Nazis? History? Yet the intercutting continues in order to heighten the drama. Or melodrama.

“Sarah’s Key,” based upon a novel by Tatiana de Rosnay, and also about the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup, is, for the most part, blunter and starker.  On July 16, 1942, two kids are playing under the sheets in their bedroom while their mother (Natasha Mashkevich, reminiscent of Diane Kruger in her beauty) smiles and does needlework. Then the knock on the door. The French official. All Jews are being rounded up. Schnell schnell! Apologies: Vite vite! The girl, Sarah Starzynski (an astonishing Mélusine Mayance), is a quick study and hides her baby brother Michel in a near-invisible bedroom closet and locks the door. She tells him not to make any noise; she promises to come back for him.

On July 16, 1942, two kids are playing under the sheets in their bedroom while their mother (Natasha Mashkevich, reminiscent of Diane Kruger in her beauty) smiles and does needlework. Then the knock on the door. The French official. All Jews are being rounded up. Schnell schnell! Apologies: Vite vite! The girl, Sarah Starzynski (an astonishing Mélusine Mayance), is a quick study and hides her baby brother Michel in a near-invisible bedroom closet and locks the door. She tells him not to make any noise; she promises to come back for him.

But if you know anything about the roundup you know there’s no coming back. The Jews were taken to the Vélodrome d'Hiver near the Eiffel Tower in Paris for several days; then they were transported by train to the Drancy internment camp; then most of them were sent to Auschwitz.

So the first half of the movie is driven by this question: Can Sarah, or someone in her family, escape and make it back in time to free Michel? That’s the key, or the palpable key, of the title. Sarah keeps gripping that key in her sweaty little hand. She holds onto it for dear life—the life of her brother, whom she promised to return for.

Intercut with this 1942 storyline is a contemporary one, featuring Julia Jarmond (Kristin Scott Thomas), an American journalist for a dying international magazine, who is finally writing that in-depth piece on the Vel’ d’Hiv roundup she always wanted to write. She and her husband, Bertrand Tezac (Frédéric Pierrot), and their teenaged daughter, are also moving into his parents’ old place in the Marais district. Then she discovers she’s pregnant. Then she discovers that the Tezacs moved into their place in August 1942—a month after Vel’ d’Hiv—and that it originally belonged to the Starzynskis, whom she researches. So how culpable are her in-laws in the roundup? How culpable is she?

From her father-in-law, who was a boy at the time Sarah finally returned, she learns the full story. We’ve already watched Sarah survive Vel’ d’Hiv and Drancy—where she is separated from her father and mother—then overcome a three-day fever and escape the camp with a companion, who succumbs to her own fever in a small French town; and with each event, Sarah’s increasing panic becomes our own. We try to add up the time. A three-day fever? Weren’t they already at the velodrome for several days? Plus Drancy. Has it been a week yet? Longer? How long can a boy survive without food and water?

As a result, the primary horrors of “La ronde.,” which are milked unnecessarily, are here almost secondary horrors. Yeah yeah, there goes the father. Yeah yeah, mother and daughter being torn apart by French officials at Drancy. But what about Michel?

Sarah convinces the old farmers who have sheltered her, Jules and Geneviève Dufaure (Niels Arestrup of “Un Prophete” and Dominique Frot, both powerfully understated), to travel with her to Paris to free her brother. By then the Tezacs have moved in, but she pushes past them, puts the key in the lock and opens the door. By which time, of course, there’s not much of her brother left to free.

As soon as we see, or see the reaction to, what happened to Michel (“We thought a bird had died in a gutter,” the father-in-law tells Julia. “We closed the windows but the smell only got worse”), I immediately thought: OK. We’re halfway through the movie. What’s going to drive it forward now?

Answer: Not much.

Julia, obsessed, keeps researching Sarah’s story: How she grew up, strong and beautiful but distant, on that farm; how she left without a word, in ’53; how she made it to America, and met a man, and married, and had a child, who grew up to be Aidan Quinn living in Florence, Italy, but how she died in an automobile accident back in ’67, which we suspect wasn’t an accident at all but a suicide, and which we discover, later in the movie, yes, we were right, it was a suicide.

The story of Michel is focused and intense while this is unfocused and uncompelling. The movie becomes less about Sarah, who’s mysterious to all who know her, including us, than about Julia, who is researching all this because... ? Who knows? Even she doesn’t know. It becomes soft and distant, with well-off people viewing tragedy in the rearview mirror and holding hands with sad smiles over dinner or drinks. It does a disservice to the child Sarah’s story by making the adult Sarah a stranger to us. One can understand her eventual suicide—how, even in America, with a new family, she couldn’t escape her horrifying past—but one still wonders who she tried to become. One wonders about the conversations she had in her head with her parents and her brother. One wonders if she felt she owed it to them to live or owed it to them to end her life. But we can only wonder because the movie keeps Sarah, as Sarah keeps the world, at a distance.

As a child, Sarah Starzynski holds onto her key at all costs. Unfortunately, writer-director Gilles Paquet-Brenner lets our key to Sarah slip away.

Saturday August 06, 2011

Aliens 'R' Us: How 9/11, the Holocaust and the Challenger disaster are evoked in “Cowboys & Aliens”

I didn't mention the following in my review of “Cowboys & Aliens” but it's been nagging at me enough to write about it now.

There are three scenes in the movie reminiscent of three real-life tragic events:

- Inside the aliens' spaceship, where humans are experimented upon to discover how to kill us (answer: easily), Jake (Daniel Craig) stumbles upon an old pile of eyeglasses and pocketwatches and things taken from victims. It's a horrific moment. Anyone who's seen any documentary about the Holocaust, particularly “Nuit et brouillard,” will be reminded of that great 20th century horror.

- The alien spaceship in the desert has the shape a skyscraper; and when Jake and company climb two-thirds of the way up and toss dynamite within, the ensuing explosion is like, you know, an explosion going off two-thirds of the way up a skyscraper. Which reminded me of the twin towers on 9/11.

- When the alien spaceship attempts to leave, it is blown up from within by Ella Swenson (Olivia Wilde), and the odd smoke configuration the blast leaves behind in the blue sky is reminiscent of the 1986 Challenger disaster.

I get why you might do 1). The aliens, after our gold—our gold, Dobbs!—are intent on perpetrating a Holocaust on the human race. They are the Nazis, we are the Jews. They are the bad guys, we are the good.

But why do 2) and 3)? In 2), the aliens are us, which makes us al-Qaeda. In 3), the aliens are us again, a sympathetic us, an us that attempts to slip the surly bonds of Earth and touch the face of God. It's completely at odds with both 1) and the entire thrust of the movie.

It could just be me, of course, seeing things that Jon Favreau doesn't. But a quick Internet search finds a few people with similar vision. Glenn Lovell over at cinemadope talks up the evocations of Challenger, while Ray Pride talks both Challenger and Holocaust at newcitynews.

I'd suggest that you decide for yourself but then you'd have to see the movie. And it's not worth the two hours of your life.

Smoky pretty things.

Tuesday August 02, 2011

Movie Review: Cowboys & Aliens (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

During the climactic battle sequence in “Cowboys & Aliens,” in which Col. Woodrow Dolarhyde (Harrison Ford) leads a rag-tag team of Indians and outlaws in an attack on an alien spaceship ensconced in the desert, while Jake Lonergan (Daniel Craig) and Ella Swenson (Olivia Wilde), having freed the town captives within, crawl deeper into the spaceship to blow it up, I was thinking the following:

Hey, there are nine lights on this side of the theater while the other side has only eight. Is that right? Yep, only eight. Where’s the missing one? Five before the exit sign on each side. That’s not it. But four after the exit sign here and only three there. And there it is. The top light is out. They should fix that.

Not a good sign.

The movie opens in a scabby section of the American Southwest, pans right, and, boom, up pops Lonergan.  He’s in a panic and in pain. He reaches for his right side, where he’s bleeding, when he notices the high-tech metal bracelet on his left wrist. He claws at it, uses a rock to try to bash it off. Captive animals, tagged and released into the wild, come to mind.

He’s in a panic and in pain. He reaches for his right side, where he’s bleeding, when he notices the high-tech metal bracelet on his left wrist. He claws at it, uses a rock to try to bash it off. Captive animals, tagged and released into the wild, come to mind.

Then three grubby men ride into view, take him for an escaped outlaw, and get ready to kill him for the bounty. “It’s not your lucky day, stranger,” the clan leader says. That “stranger” part is correct, since Lonergan doesn’t even know his own name, but the rest? The reverse. Lonergan attacks and kills all three, takes their boots, belts and guns, and heads off into the nearby town of Absolution to fix himself up.

Not a bad open, I thought. A classic western stranger. A new “man with no name.” Plus Daniel Craig is cool and intense in the usual Daniel Craig way.

In Absolution, he keeps running into interesting characters played by interesting character actors: Meacham (Clancy Brown), the town preacher, and moral authority of the film; Percy Dolarhyde (Paul Dano) the spoiled son of Woodrow, who likes to shoot up the town; Doc (Sam Rockwell), the town saloonkeeper and everyman, who doesn’t know how to shoot a gun and thus can’t defend himself or his Mexican wife; and Sheriff John Taggart (Keith Carradine), sighing, and trying to keep the peace.

I was even beginning to enjoy myself. I’d always liked the whole “cowboys and aliens” concept. As soon as I heard it, I thought: Of course. If aliens land, why would they only land in the 20th century? Why couldn’t they land earlier when we were truly, hopelessly outmatched? Pit them against grubby men with Colt revolvers. Combine the classic “stranger” narratives of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The movie, I knew, had a low Rotten Tomatoes score, 44%, but, in the darkened theater, I was beginning to think the critics were wrong.

Then the movie began to go wrong.

At one point, Meacham says to Jake, “I’ve seen good men do bad things and bad men do good things,” which is a bit too all-encompassing for the circumstances. It’s the movie announcing its theme as subtly as a fifth grader writing a theme paper.

There’s a snatch of dialogue between Doc and his wife that suggests an unnecessary, unwelcome backstory. These begin to multiply. Col. Dolarhyde spoils one son but ignores the other, Nate Colorado (Adam Beach), an Indian orphan from a long-ago attack whom he’s raised without love or attention. Sheriff Taggart has a grandson who keeps tagging along and taking up valuable screen time. Doc is taught to shoot a gun.

Plus Jake is not only not “a man with no name” but a man with several pasts. He’s an outlaw who led a gang that robbed gold from Dolarhyde. No, wait, he abandoned that gang for the woman he loved, a former whore. No, wait, he finally remembers the following scene. He comes home, splashes gold pieces on the kitchen table, and his wife, the former whore, objects.

She: You gotta take it back.

He: Like hell I will.

She: That’s blood money!

He: That’s gonna get us what we need!

Of all the scenes to remember, he has to remember the one with such lousy dialogue.

After aliens attack and lasso townsfolk from their spaceships, and Jake downs one such ship with the high-tech gadget on his wrist—he and his wife were taken before, we find out; he escaped—a posse is formed to track the wounded alien. Dolarhyde wants his son back, Doc his wife, the boy his grandfather, so they do what they know, form a posse, even as they’re unsure what they’re tracking. Is it a demon? Is God punishing them? They have no clue what’s going on but they act as if they’re familiar with the tropes of the genres. The whole alienness of the situation should’ve increased tenfold. They should’ve gotten on their knees and prayed to God. They should’ve clung to Meacham, the preacher, and begged for understanding.

Is all the good dialogue in the movie Meacham’s? As they ride along, slowly, Doc complains about his life as if he were a twentysomething liberal arts grad, and suggests, from the evidence, that there’s either no God or one who doesn’t care about him. Meacham responds: “You’ve got to earn His presence; you’ve got to recognize it; then you’ve got to act on it.” Wow. That’s pretty good for a preacher in the middle of a posse. So who’s the first to die? Meacham, of course. “We’re screwed now,” I thought.

Indeed. The aliens, it turns out, are merely scouts after our gold, and they’re kidnapping our people to see what it takes to kill us, all of us, but that’s not the problem with the movie. The problem with the movie is this: When deciding between doing what’s true for the characters or what furthers the clichés of the genre, the filmmakers, director Jon Favreau and his six screenwriters, always opt for the latter. They’re not interested in the perspective of their 19th-century characters; they’re only interested in the perspective of their 21st-century audience. Dolarhyde and Lonergan are assholes not because life is hard but so they can redeem themselves in the end. The town’s name is a giveaway. The theme Meacham stated earlier is a giveaway. Lonergan, always on the verge of leaving, always has to return as if it’s a surprise. Doc, like Sgt. Powell in “Die Hard,” has to shoot to kill at just the right moment. Dolarhyde has to bond with the boy; he has to come to an understanding with Nate; he has to save the Indian chief so the two, in the midst of battle, can give each other a nod of understanding.

It’s all so false and awful that the difference between the number of lights on each side of the theater suddenly seems like a fascinating area for your mind to go.

Friday July 29, 2011

Movie Review: Buck (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Of Buck Brannaman, the subject of Cindy Meehl’s documentary “Buck,” and a man who spends 40 weeks a year traveling the country giving seminars on horses, one of the talking heads says, “God had him in mind when He made a cowboy.”

Buck certainly fits some of our preconceptions of cowboys. For someone who talks for a living, he doesn’t talk much; and for someone who’s often in the center ring, he's got an aw-shucks manner. He ambles rather than walks. He’s married with children but spends most of his days alone and carries that solitude with him. He knows horses, and through horses, people. He does rope tricks. He drinks his coffee black. He’s named “Buck.”

He also expands our definition of what it means to be a cowboy.

He also expands our definition of what it means to be a cowboy.

“I was watching ‘Oprah,’” he begins at one point, then pauses and manages a crooked smile. “I don’t know if I should admit to that.”

Starting not breaking

He “starts” horses, he says, he doesn’t break them. His approach is discipline without punishment, empathy without sentimentality. Horse people come to his seminars skeptical and leave stunned. Their tough love doesn’t work. Their soft love doesn’t work. But Buck gets in the ring and in five minutes their horse is following him around like a dog. He takes an unfocused horse and focuses him. He takes a skittish horse and calms him. The advice he gives goes beyond horses.

- “Make it difficult for the horse to do the wrong thing and easy to do the right one."

- “You can't just love on them and buy them lots of carrots. Bribery doesn't work with a horse. You'll just have a spoiled horse.”

- “When you’re dealing with a kid or an adult or a horse, treat them the way you’d like them to be, not how they are now.”

He has a great, empathetic description of what a horse is allowing you to do when you ride it. On his back? By his neck? That’s where he’s attacked. So when you climb on him to ride him, he’s trusting you enough, or respecting you enough, to allow you into this vulnerable spot. Respect that.

“Everything’s a dance,” he says. “Everything you do with a horse.”

Horses can sense, I’m sure, his gentle spirit, as surely as Robert Redford, another talking head in the film, sensed it. They met when Buck was an advisor on Redford’s film “The Horse Whisperer.” Redford talks about filming a particularly difficult scene in which the film’s injured horse is supposed to go up and nuzzle the daughter, played by a young Scarlett Johansson, on cue. It’s a trick horse, a trained horse, but not a horse affiliated with Buck, and they spend all day and can’t get the shot. Then Buck suggests his horse. They get the shot in 20 minutes.

So who is this man who starts rather than breaks horses? He's someone who was almost broken himself.

“When something is scared for their life, I understand that,” he says.

I wouldn’t be surprised if I saw Buck some Saturday morning in 1970. He and his brother, rodeo stars who could do rope tricks blindfolded, were in a “Sugar Pops” commercial back then. And like another child star back then, Michael Jackson, Buck was controlled by, and abused by, his father. “He beat us unmercifully for not putting on a perfect performance,” Buck remembers. Buck’s mother would sometimes act as a barrier between the rage of the father and the vulnerability of her sons, but she died when Buck was young and he knew then that he was truly alone in the world. We get this story by and by. How a gym teacher in high school saw the marks on Buck’s back. How he alerted the authorities. How Buck wound up with a foster family in Montana that was raising 23 kids, and the father immediately gave him gloves and put him to work on the farm, and how that’s just what Buck needed. A purpose. The gloves were so special he didn’t even put them on when handling barb wire.

Loose ends