Tuesday April 04, 2023

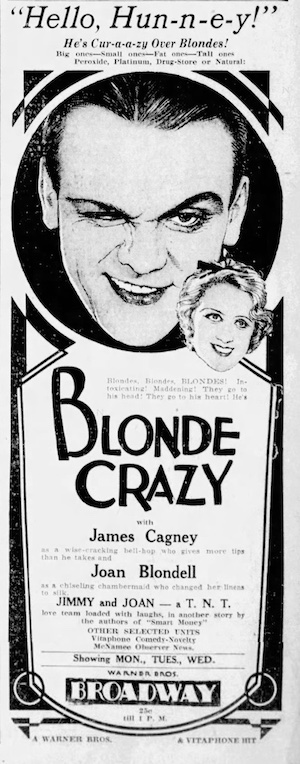

Movie Review: Blonde Crazy (1931)

WARNING: SPOILERS

This was James Cagney’s first lead role after he became a star in “The Public Enemy”; and though gangsters like Tom Powers are what he’s known for, Bert Harris is actually more indicative of his early screen persona. In the precode era, Cagney was more grifter than gangster.

“Blonde Crazy” (née “Larceny Lane”), a tale told in four or five grifts, is not much of a movie but it’s fun. It feels like a B picture or exploitation flick in the way it’s steeped in the culture of the moment—as if it didn’t have the money to extract itself from the culture of the moment. You feel it mostly in the lingo. “You’re not a collar ad, but you're not bad looking.” “I could eat the hip off a horse.” “Aw, you’re as wet as he is.” And of course Bert’s term of endearment for any and all women: “Huuuuuhhh-ney!”

But my favorite example is the use of dynamite as metaphor. It’s not a compliment yet:

But my favorite example is the use of dynamite as metaphor. It’s not a compliment yet:

“I’d stay away from those bellhops, they can’t do a girlie any good. And the worst monkey of them all is that guy Bert Harris. He’s dynamite. Everyone in this joint owes him money from those crooked dice of his.”

Dynamite as a pejorative makes way more sense, doesn’t it? Makes you wonder when it become a positive. And why. And what that says about us.

Scrapbooking

Bert Harris is both ass man and a bit of an ass. He’s a bellhop joyously checking out every passing blonde in the midst of myriad smalltown scams. We never see those crooked dice of his, but we do see the machinations involved in getting Anne Roberts (Joan Blondell) hired—sweet-talking, fast-talking and bribery—and then trying to get into her pants. For the latter, he winds up with his face slapped. That happens a lot. Consider the movie the revenge of Mae Clarke in the beating Cagney takes from women.

Bert may be dynamite but he’s still an amateur—he even keeps a scrapbook of newspaper clippings involving various grifts he’d like to try. When does he begin to think big? I guess when A. Rupert Johnson Jr. shows up (Guy Kibbee, in his first of five Cagney movies). He’s a hotel guest who also expects a little something-something from Anne, and harrumphs mightily when he doesn’t get it. So Bert shows him some Prohibition-era hootch, says it’s $10 a bottle, and when Rupert wonders if that isn’t a little steep, Bert intones slyly: “Not if the blonde chambermaid likes it.” Then with a pal (Nat Pendleton) playing cop, they catch Rupert canoodling in the back of his car with both Anne and the hootch. Desperate to avoid a scandal, our grifters are suddenly $5,000 richer.

All of this takes place, per an early title, in a “leading hotel of a small mid-western city.” The $5k bankrolls their move to a better hotel in a bigger city—Chicago. Except before Bert took the suckers; in Chicago, he’s the sucker. He and Anne fall in with two other grifters, Dapper Dan and Helen (Louis Calhern and Noel Francis), and they make a chump of him. While Helen flirts, Dan pretends he’s passing phony $20 bills—gets them from a guy at three-to-one—and Bert wants in. The $15k they get—real money, it turns out—winds up in a drawer in Bert’s hotel room—along with the previously earned $5k. Except they’ve already cut through the wall on the other side. So instead of cash, Bert is left holding a taunting note:

Darling:

paste this in your scrap book

love and kisses

Helen

Because he can’t bear to let Anne know he’s been taken, he grifts again—though later, Anne oddly sees the enterprise as beneath him. “Out-and-out thievery is not your style, Bert,” she says. “The worst thing you did was take from a lot of wise guys, cheat a lot of cheaters.” Which … sorta? Rupert was a lech, not a cheater. Plus the new grift isn’t bad. He finds out about a high society wedding, goes to a jeweler as a rep of the family, has an expensive necklace sent to the family home, then shows up as a rep of the jeweler saying, “Sorry, we sent this to the wrong house.” Now he’s got the expensive necklace, which he hocks. When the very Jewish pawn shop owner tries to chisel him down, we finally see a bit of Tom Powers. He grabs the guy by the back of the neck, calls him “Three Balls” (for the traditional pawn shop logo) and strongarms him into a better deal. “My, but you’re a tough guy,” the pawnshop owner says. “Not tough. Just mercenary,” Bert sneers before slapping the man with the dollar bills.

Now it’s onto New York, and guess who Anne runs into? “Einstein?” Bert jokes. Nope, Dapper Dan. That’s how she finds out Bert got grifted. Helen is already out of the picture so now it’s time to take Danny boy with another not-bad scam. Dan thinks Anne is working with him to grift the florid Col. Bellock (William Burgess), but it’s the opposite; she’s working with the Colonel. Late to the racetrack, Dan suggests some friendly wagers on races they’ve already missed, knowing one of their gang will call ahead to find out who won, then switch numbers on passing license plates to clue Dan. But the Colonel has the real winning numbers, and at the track Dan discovers he’s out $7500. He can’t figure what went wrong until he finds the taunting note Anne leaves behind.

The most fascinating thing about this revenge grift? It’s about 10 minutes of screentime and we don’t see Cagney. At all. It’s all Blondell. Can’t imagine a modern star taking such a backseat.

Now that that’s solved, what’s the drama/conflict? All along, Anne has complained that Bert just cared about money, blondes, and grifts.

- “Oh Bert, you’re such a boy. You’ll never grow up!”

- “Oh, Bert, sometimes you act like a kid.”

Now he wants to get married, he wants to travel to Europe, but Anne tells him he's too late: "I’m in love with someone else.” It’s the guy who helped her get the cinder out of her eye on the train, banker Joe Reynolds (played by a young and very good-looking Ray Milland). Bert watches their wedding from a nearby taxi cab, and when the cabbie asks if it’s a wedding or a funeral, Bert responds: “Both.” Nice line. Then he’s off to Europe by himself. When he returns a year later, he’s lost the spark.

Now he wants to get married, he wants to travel to Europe, but Anne tells him he's too late: "I’m in love with someone else.” It’s the guy who helped her get the cinder out of her eye on the train, banker Joe Reynolds (played by a young and very good-looking Ray Milland). Bert watches their wedding from a nearby taxi cab, and when the cabbie asks if it’s a wedding or a funeral, Bert responds: “Both.” Nice line. Then he’s off to Europe by himself. When he returns a year later, he’s lost the spark.

What gets him moving again? Anne. She’s in trouble. OK, Joe’s in trouble. He embezzled $30k, invested it, lost it. Bert figures a cover: Since no one knows the funds are missing, have someone else—him—steal the rest, and they’ll figure it was all just part of the same robbery. Would’ve worked, too, except Joe is not just a cheat but a rat. He and the cops are waiting for Bert. That’s gotta be one of the worst ways to say “thank you” ever. Not to mention moronic. Imagine they’d actually caught Bert. He could’ve spilled the beans, and when Joe objected, he could’ve just said, “Check the satchel. There’s $30k missing in negotiable bonds. That’s on him.” At which point, Joe would’ve bolted like the rat he is. Instead, here, Bert lams it, there’s a car chase, he’s shot in the back, his car goes into a storefront. But he lives.

This is another way Bert Harris is more indicative of early Cagney than Tom Powers: He doesn’t die. We always think of Cagney getting plugged in the final reel, but in the 22 starring roles between “Public Enemy” and “Angels with Dirty Faces,” he only dies twice: “He Was Her Man” (1934) and “Ceiling Zero” (1936). Both deaths are sacrificial/heroic. Generally what happens to him is Hollywood 101: he beats the bad guys and gets the girl. He also has a tendency to repeat his catchphrase at the end, too: “Why, if I thought you meant that…” to Loretta Young; “I’ll put a gold spoon right in your kisser” to Mary Brian.

Here, too. He may be in prison, but Anne shows up, tells him about Joe’s perfidy, tells Bert she loves him and will wait for him. Once she leaves, overjoyed, he returns to the Bert we’ve always known. He tells the female prison guard:

If I had the wings of an angel, huuuuuu-ney

Over these prison walls I would fly!

It’s not just a return to his catchphrase, it’s a tweak on “The Prisoner’s Song,” a 1920s staple that several years later the Dead End kids would sing at the end of “Dead End” in 1937. That song is probably why, in their next big role, they became angels with dirty faces—playing against Cagney, of course. The connections never stop.

You dirty rats

We all know the ’60s-era variety show Cagney imitation, “You dirty rat,” and we all know it’s a line he never said, but it didn’t come from nowhere. He probably came closest to saying it in “Taxi!,” when he says to the guy who killed his brother, “Come out and take it, you dirty yella-bellied rat, or I’ll give it to ya through the door!”

Here, too. When Anne tells him about Joe’s treachery, he says this:

Why, the dirty, double-crossing rat! I’d like to get my hooks on him I’d tear him to pieces!

Both movies were written by John Bright and Kubec Glasmon (née J.J. Glassman), Chicagoans who also wrote “The Public Enemy” and helped make Cagney’s career. They gave us the early Cagney lexicon, and were assigned to the budding star until Bright ran into trouble with Jack Warner, Darryl Zanuck, et al. and that was that. They were also different types: the Polish-born Glasmon tended toward respectability, the American-born Bright toward rebellion (he helped create the WGA). I don’t know if this is a lesson but the respectable Glasmon wound up dying of a heart attack at age 40 in 1938, while the rebellious Bright, who wound up in B pictures and then blacklisted, spent decades pickling himself and lived until 1989. His memoir, “Worms in the Winecup,” has nice nuggets but is indicative of a scattered mind. He kind of disses Glasmon, calling him “at best semiliterate,” but he adds that he had “a feel for character … his ear for speech patterns, particularly seamy street talk, was accurate and captured flavor.” One wonders if that’s where some of the flavor of this movie came from.

-- A shorter review of this film can be found here. It's from July 1999.

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)