Saturday March 23, 2024

Movie Review: The Maltese Falcon (1931)

WARNING: SPOILERS

There’s a surreal quality to watching the original 1931 version of “The Maltese Falcon.” It’s like explaining a dream to a friend: You were you, but not really you. Here, Sam Spade is Sam Spade, but not really Humphrey Bogart.

Actually, not at all Humphrey Bogart.

All his teeth

He’s Ricardo Cortez (nee Jacob Krantz), a wannabe Valentino by way of Zeppo Marx, and his Sam Spade isn’t exactly the cool, professional hero of John Huston’s 1941 classic. He’s a lothario—leering at the pre-code women with all his teeth.

He’s Ricardo Cortez (nee Jacob Krantz), a wannabe Valentino by way of Zeppo Marx, and his Sam Spade isn’t exactly the cool, professional hero of John Huston’s 1941 classic. He’s a lothario—leering at the pre-code women with all his teeth.

At his office he kisses goodbye to a midday tryst (legs only) before nuzzling the neck of his semi-resistant secretary, Effie (Una Merkel), who then ushers in the movie’s femme fatale, Ruth Wonderly (Bebe Daniels), with the familiar line, “You’ll see her anyway—she’s a knockout.” In the midst of this he gets a call from Iva Archer (Thelma Todd of Marx Bros.’s fame), the pain-in-the-neck wife of his partner Miles Archer (Walter Long), and yes he’s banging Iva, too.

All of which makes us aware of the great lie in the ’41 version: Sam Spade is a skunk. Sure, no midday tryst, and he and Effie banter like pals, but he is banging his partner’s wife. That shit ain’t cool. But Bogie gets away with it because, well, he’s cool. He doesn’t leer at anyone or nuzzle anyone’s neck; he’s a professional throughout. Plus he’s friends with everyone in town: this cop, that cab driver, the other hotel dick. It’s the ’41 Miles Archer (Jerome Cowan) who acts the skunk—checking out Ruth Wonderly and all but going hubba hubba. “You’ve got brains—yes, you have,” Spade tells him sardonically, and next thing you know Archer is killed in cold blood and no one cares. He had $10k in insurance, Spade says, no children, and a wife that didn’t like him. Plus, we could add, a partner who couldn’t wait for the body to get cold before taking his name off the door.

The ’31 version of Archer is way more sympathetic. True, he’s got a face like a Mack truck, but when he overhears his wife confessing her love to his partner we feel his pain. Once Ruth leaves, we figure he’s going to wipe the floor with Sam. Instead:

Archer: Any phone calls for me, Sam?

Spade: Ohhhh, yes. Your wife called.

Archer: Yeah? What did she have to say?

Spade: Ohhhh, wanted to know when you were coming home. And she said she missed ya an awful lot!

Is that an unintended irony of the Production Code? When you sweep sex under the rug, you lose accountability. You lose morality. You kind of make it OK to covet thy neighbor’s wife. Way to go, Catholics.

Here, Archer’s body is found in a back alley near a chop suey joint—rather than down a construction site—but like with Bogart’s version Sam has no time to check on it. Unlike in the Bogart version, he stops and exchanges a few words of Cantonese with the owner of the chop suey joint, Lee Fu Gow. This is crucial info, it turns out. Spade now knows (even if we don’t) that Archer was killed by a woman. None of this was in the Huston version, by the way, because none of it was in the Dashiell Hammett novel. You can thank the ’31 screenwriters: Maude Fulton (“Other Men’s Women”), Brown Holmes (“I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang”) and an uncredited Lucien Hubbard (“Smart Money”).

There’s a lot of such little differences between films. We get no opening title cards about the Knight Templars of Malta and Charles V of Spain, we don’t see Archer being killed, there’s no shaking Wilmer's tail or booting him from the lobby of the Hotel Belvedere. Wilmer doesn’t even show up until the big meeting with Casper Gutman, and that meeting is a one-fer. Gutman begins it, then Joel Cairo shows up in the next room, returning to the fold, as it were, with intel that the black bird is arriving on the ship La Paloma, docking that day. So we better understand why Gutman slips Spade a mickey—he doesn’t need him anymore. What we don’t get is why Joel Cairo bothers to return to the fold. If he has the intel, why share it with the Fat Man?

Overall, there’s less playfulness with Cairo. Or the playfulness is Effie’s rather than the movie’s. She tells Sam he has a gorgeous new customer, and as Sam gets ready to sink his teeth in, in walks Joel Cairo (Otto Matieson). There’s no “Gardenia,” no lilt to the soundtrack, no supposition that he’s gay; and after Sam knocks him out there’s barely anything in his pockets. Just the wallet. Lorre has the wallet, three passports, foreign coin, a ticket to the Geary Theater and a scented handkerchief. (Cue lilt again.) He has a storyline in his pockets. He has a life. Plus he’s played by Peter Lorre. (No offense to Matieson, a Dane who played Napoleon Bonaparte several times in the silents.) Gutman, meanwhile, is played quite sweatily by Dudley Digges, who is memorable as the evil “boys prison” warden in “The Mayor of Hell.” Wilmer? That’s Dwight Frye, the original Renfield in Universal horror flicks, as well as Dr. Frankenstein’s assistant (Fritz/Karl) in the first Frankenstein films. They’re no slouches, in other words. They're also not Lorre, Sidney Greenstreet and Elisha Cook, Jr. Not close.

One improvement? While Mary Astor is great at playing a school-marmish type who can suddenly get into a catfight with Lorre’s Joel Cairo, I have trouble seeing Bogart’s Spade losing his heart to her. She’s not the “knockout” she’s made out to be. Bebe Daniels is closer to that, and Cortez’s Spade doesn’t really fall for her that hard. It’s more lust than love. Daniels, who played the star who has to break her ankle so Ruby Keeler can rise in “42nd Street,” was 30 years old at the time, but had been acting in movies for more than 20 years. In 1910, in just her second movie, she played Dorothy Gale in a short version of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.” One wonders if she was destined to play roles that, in later, better productions, would be made more famous by someone else.

Repping SF

And the hits keep coming—if slightly off-key:

- “We didn’t believe you, we believed your $200.”

- “You’re pretty good. As a matter of fact, you’re very good. It’s chiefly your eyes, I think, and the throb you get in your voice when you say, ‘Oh, be generous, Mr. Spade.’”

- “A statuette. The black figure of a ... bird.”

- “Permit me to remind you, Mr. Spade, you may have the falcon, but we most certainly have you.”

- “Why, I feel toward Wilmer exactly as if he were my own son.”

- “You palmed it, Gutman. ... I said you palmed it.”

Each line is great, but you miss Greenstreet’s harrumph, Lorre’s whine, Bogart’s cool.

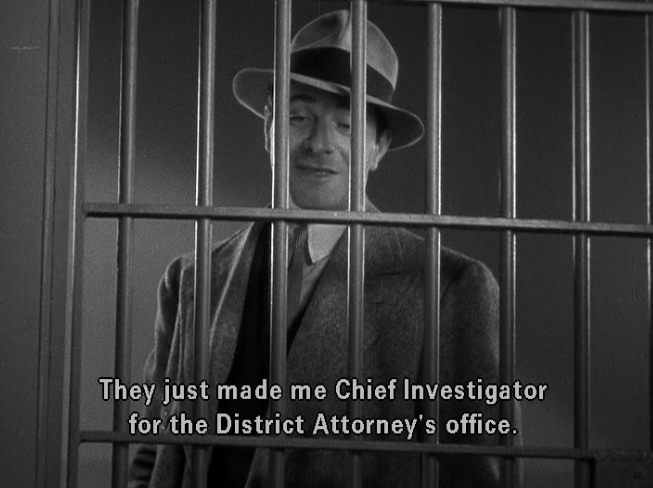

The ’31 version is directed by Roy Del Ruth, who directed some good early Cagneys (“Blonde Crazy,” “Taxi!”) and crappy later ones (“West Point Story,” “Starlift”), and it’s still early in the sound era so the camera doesn’t do much. Everything feels two dimensional. It’s straight-on shots, often with just one person in the camera frame. There’s no sense of humor to the movie, and no sense of tragedy. When the Falcon is finally uncovered, there’s nothing monumental about it. You don’t lean in the way you do in the Huston version. And that great ending, where the elevator gate clangs shut on Mary Astor like the bars of a jail cell, and then descends as if into hell while the soundtrack pounds, well, there’s nothing close to that here. Huston ended it like the best of Hitchcock—ripping the Band-Aid off—while this one just keeps going. Spade, now the chief investigator for the DA’s office, visits a disheveled Ruth/Brigette in her cell, and she tries to coax some of her moxie back. No go. Afterwards, he privately tells the female guard to give her everything she wants. When the guard asks where to send the bill, his mood becomes oddly buoyant: “The district attorney’s office!” he practically shouts. Not exactly “The stuff dreams are made of.”

Oh, another difference? How they open the film. How do you let viewers know we're in San Francisco? Huston opens with a nice shot of the Golden Gate Bridge. Of course. They don't do that here or the simple reason the Golden Gate Bridge didn’t exist in 1931. They began building it in ’33 and it opened to traffic in ’37. So what repped San Francisco in 1931? The Ferry Building.

SLIDESHOW

Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)