Movie Reviews - 2011 posts

Monday December 19, 2011

Movie Review: Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS?

It would be nice if kids or teenagers left the Guy Ritchie “Sherlock Holmes” movies wanting to be smarter. These things are roller coaster rides, like any successful Hollywood action franchise, but at least the guy at the head of the roller coaster isn’t a pun-swilling gigantus, like Arnold Schwarzenegger, or an ordinary schmoe yapping out of the corner of his mouth, like Bruce Willis. At least he’s a supersmart guy. So maybe it’ll encourage a few kids out there to be smart or get smart. One can hope.

On the other hand, Sherlock Holmes (Robert Downey, Jr.) and Dr. Watson (Jude Law) have, under Ritchie’s direction, become so glib in their smartness, in their ‘science’ of deductive reasoning, that, halfway through their latest adventure, the horribly subtitled “Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows,” they began to remind me of the satiric 1960s-era Batman and Robin (Adam West and Burt Ward) solving the Riddler’s riddles.

Here’s Batman and Robin from 1966. What has yellow skin and writes? A ball-point banana! What people are always in a hurry? Rushing? Russians! “I’ve got it!” Robin says, snapping his fingers. “Someone Russian is going to slip on a banana peel and break their neck!” “Right, Robin,” Batman replies with gravitas. “The only possible meaning.”

For Holmes and Watson, it’s this dirt on this page, and that wine stain on that page, not to mention such-and-such an inky residue, leading them, of course, to that wine cellar near the printing press in Paris! The only possible meaning.

For Holmes and Watson, it’s this dirt on this page, and that wine stain on that page, not to mention such-and-such an inky residue, leading them, of course, to that wine cellar near the printing press in Paris! The only possible meaning.

The movie, while it mostly ignores the Arthur Conan Doyle stories, is bookended by homages. We see Dr. Watson actually writing a Sherlock Holmes adventure, which Conan Doyle’s Dr. Watson did, and in 1891, which is the year Conan Doyle’s first story, “A Study in Scarlet,” appeared in The Strand Magazine. And we get Reichenbach Falls in the end.

But it begins with terrorism. Things are blowing up and the newspapers of the day are blaming the right or left, the nationalists or anarchists, depending; but, Watson writes, “my friend Sherlock Holmes had a different theory entirely.” Cut to: a package changing hands in the dirty streets of London. The last hands belong to Irene Adler (Rachel McAdams), functionary to Prof. Moriarty (Jared Harris of “Mad Men”) and love interest to Sherlock Holmes, who, disguised as a Chinese opium addict, suddenly appears at her side, warning her of unsavory men following her. Ah, but he’s mistaken. They’re guarding her, against him, and she leaves him in their care. Which leads to our first example of 19th-century fisticuffs, or, more precisely, slow-mo and super-deductive 21st-century martial arts madness.

Are we tired yet of Holmes imagining the fight before the fight even though he has no idea whom he’s fighting? Are we tired yet of explosions, of bullets ripping through trains and trees but always missing our lead characters? Are we tired yet of all the anachronisms, of machine-gun pistols and faultless plastic surgery and the general 21st-century superquick pace of movies—zipping from London to Paris to Germany to Switzerland and back to London again? Or is it just me?

The key to the movie is how to keep Dr. Watson involved. He’s about to get married, remember, and does, to Mary (Kelly Reilly), so he should be out of the picture. But Holmes bolts after the ceremony to confront Prof. Moriarty, who has already killed Irene Adler with a rare form of tuberculosis, and who then threatens the newlyweds. “When two objects collide,” Moriarty tells Holmes, “there’s always damage of a collateral nature ... I’ll be sure to send my regards to the happy couple.”

Soon after Watson and Mary board a honeymoon train to Brighton, assassins arrive, bullets fly, and Holmes, watching over the newlyweds, protects Mary, and the movie franchise, by pushing her from the train and into a river, where brother Mycroft (Stephen Fry) awaits in a rowboat to take her to safety. Phew. Thank God she’s gone. We can continue.

To Paris, and gypsies (including Noomi Rapace of “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo”), and a bombing at the Hotel d’Triomph; then to Germany and a munitions factory and a nasty bit of torture; then to Switzerland and another assassination attempt and the final tumble at Reichenbach Falls.

Moriarty’s plan? Corner the market on munitions and start a war. Yawn. Holmes prevents the immediate war but Moriarty, and we in the audience, and most likely Holmes, know it’s a stopgap. “War on an industrial scale is inevitable,” Moriarty tells Holmes. “All I have to do is wait.” Which is when Holmes reveals he’s gotten hold of Moriarty’s booklet of holdings, and, with brother Mycroft, Mary and the underutilized Inspector Lestrade (Eddie Marsan), depleted it. Cue anger flaring in Moriarty’s eyes. Cue both men imagining the fight before it happens. Cue Holmes seeing his demise. Cue the tumble into the waterfall.

Holmes’ fans know he survives. Back in 1891, Conan Doyle wanted to kill off his famed character, of whom he was tired, but there was such a yap of protest that he brought him back again, with convenient explanations for his survival. So my only question, as I watched a saddened Dr. Watson finish his story of the demise of Sherlock Holmes, typing in THE END, was whether the filmmakers would give hints that Holmes was alive or save it for the second sequel. Neither. They showed us Holmes alive, mischievously adding a question mark to Watson’s manuscript: THE END? Which, I admit, I thought was a nice touch.

But overall the script by the Mulroneys, Michele and Kieran, isn’t as clever as the first, which was written by a gang of four. The characters are now broader, the explosions bigger, the roller coaster ride blurrier. I was bored. Trees getting blown up don’t excite me. Good dialogue excites me.

You know which Holmes excites me? The one from the new BBC series, “Sherlock,” starring—and this has got to be the greatest British name that Charles Dickens didn’t invent—Benedict Cumberbatch. It’s set in modern times. He texts, he’s got a website, and Dr. Watson (Martin Freeman, who played Tim on “The Office”) is a veteran of the Afghanistan war. They bring Holmes to the 21st century. The Guy Ritchie films keep Holmes in the 19th century but lavish him with the flotsam and impatience and violence and general stupidity of ours. They’re about a sequel away from the ball-point banana.

You know how Holmes imagines the fight before the fight? I wish the filmmakers, Guy Ritchie, et al, would imagine the next sequel before the next sequel, see the shoddy result, and do the filmmaking equivalent of tumbling into Reichenbach Falls. The End. No question mark.

Friday December 16, 2011

Movie Review: Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Murky.

That’s the word that comes to mind when watching Tomas Alfredson’s “Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy.” The morality is murky, the mise en scene is murky, the code-language is murky. The film is a corrective for anyone who misses the Cold War.

But is the plot too murky? Or truncated? The movie is based upon the 432-page Cold War novel by John le Carré, which was made into a seven-part, five-and-a-half-hour BBC miniseries starring Alex Guinness in 1979. Now it’s down to two hours. In that time, amid much silence, code language, and the cold vacuity of gray-brown institutional buildings, we meet a dozen or more characters, five of whom could be traitors, all of whom are given further codenames, the titular codenames, while being investigated by George Smiley (Gary Oldman), the career spy who is pulled from a forced retirement, and who may be a suspect himself. By the time we get a handle of who’s who and what’s what, it’s time for the big reveal, and we still barely know “tailor” and “soldier,” which eliminates half our suspects. So who could it be? Oh, right. Him. There you go.

Of course the big reveal, for some, is about as much a reveal as who killed Hamlet’s father. The story is so well-known, particularly in Great Britain, that at this point it’s more about form than content: “How is the story told?” rather than “What happens?” And in this, Alfredson (“Let the Right One In”) triumphs. In “Three Days of the Condor,” a 1970s-era CIA director is asked if he misses the kind of action he saw in the intelligence field during World War II. “I miss that kind of clarity,” he responds. “Tinker Tailor” is all about that lack of clarity. It’s about murkiness. Le Carré has already called it the best adaptation of his work.

It begins in suspicion and in the negative. “You weren’t followed?” Control (John Hurt) asks Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong), a former head of the Scalphunters division. “I want you to go to Budapest,” he tells him. “This is not above board,” he tells him.

It begins in suspicion and in the negative. “You weren’t followed?” Control (John Hurt) asks Jim Prideaux (Mark Strong), a former head of the Scalphunters division. “I want you to go to Budapest,” he tells him. “This is not above board,” he tells him.

Apparently a Hungarian general wants to come over but in Budapest things go wrong and Prideaux winds up dead. It’s such a fiasco that Control, Chief of the Circus, which is the nickname of the Secret Intelligence Service, which is more commonly known as MI6, is dismissed, along with his deputy, Smiley. This is handled so subtly that I missed it. Wait a minute, what? “A man should know when to leave the party,” Control says. “Smiley is leaving with me,” Control says. And that’s that. These are men who reveal little, after all, Smiley most of all, so I missed the power struggle in those 14 words. Control is soon dead while Smiley swims with elderly men, head gliding above the water, at Hampstead Pond. At this point, we’ve been given three characters: two are now dead and one is retired. Alfredson giveth and taketh. He leaves us nothing to hold onto. The proper feeling for the rest of the story.

Besides, one of the characters turns out to be not dead, Prideaux, whom we see teaching French in some country school, recruiting a sad, fat kid to be his lookout. Is this a flashback? What is this?

Besides, one of the characters turns out to be not retired. When Ricki Tarr (Tom Hardy), a Scalphunter apparently gone rogue, shows up at the home of Oliver Lacon (Simon McBurney), the permanent undersecretary, with the same news that Control told Prideaux at the open— there’s a mole at the top of the Circus—Smiley is recalled to investigate. He reacts to this news quietly, without emotion, but his words pack a punch. “I’m retired, Oliver,” he tells Lacon laconically. “You fired me.”

But he accepts the job and chooses two men, Peter Guillam (Benedict Cumberbatch) and Mendel (Roger Lloyd-Pack)—impeccable, one assumes—and off they go, slowly and steadily.

Control’s suspicions centered on five men, whom he gave code names from a British children’s rhyme: Tinker, Tailor/ Soldier, Sailor/ Rich Man, Poor Man/ Beggar Man, Thief. (In the U.S., we borrowed the second stanza.) Thus:

- Tinker: Percy Alleline (Toby Jones)

- Tailor: Bill Haydon (Colin Firth)

- Soldier: Roy Bland (Ciaran Hinds)

- Poor Man: Toby Esterhase (David Dencik)

- Beggar Man: Smiley

Alleline, with access to a high-ranking Soviet source, codenamed “Witchcraft,” has now ascended to the top of the Circus. Haydon, best friend to Prideaux, is a ladies man always sniffing after the new secretaries. (He even seduced Smiley’s wife, news that comes to us in pieces.) Bland is blunt, Esterhase a toady. It’s one of them. Or none of them. Since Smiley was not above Control’s suspicion, he’s not really above ours, either.

Other bits come into play. George visits Connie Sachs, a retired Circus researcher, dismissed because of her suspicions of a Soviet defector, Polyakov, whom she sees, in old footage, being saluted during a May Day parade. If he was a soldier, she asks, why hide it from us? But when she brought her suspicions to Alleline, she was told, as Control was told, that she was losing her grip on reality.

After interrogating Prideaux (he hadn’t been killed: merely shot and tortured for months), Peter and Smiley share a bottle of Scotch in a hotel room, talking about Karla, their counterpart on the Soviet side. It's a great scene. Smiley owns up that he once met him, in ’55 in Dehli, after Karla had been tortured by the CIA. “No fingernails,” Smiley says matter-of-factly, holding up his right hand. The assumption was Karla would be killed when he returned to Moscow, so Smiley tries to convince him to stay in the west, and talks about all we have here; then he talks about Karla’s wife, and how she’ll be ostracized once he’s killed, and surely he wouldn’t want that. It’s such a smart scene, and so beautifully acted. Time and again, we see Smiley lose himself in thought, in remembrance. I’ve read that some think Oldman’s performance in the movie is too minimalist, but there’s always something behind the minimalism. It’s not just a blank. And here? Where, tipsy, he’s allowed to show a modicum of emotion? My god. One wonders how actors lose themselves in thought this way. Smiley admits that in trying to win over Karla he’d revealed too much of himself—how much his wife meant to him—while Karla, silent, got on a plane, keeping Smiley’s cigarette lighter: To George, from Ann. All my love. But in revealing nothing, Karla had revealed something. Smiley:

That’s how I know he can be beaten. Because he’s a fanatic. And the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt.

Then he tells Peter (because he knows?) that Peter will now be a target and better get his house in order. Cut to: Peter breaking up with his boyfriend, then crying to himself when he’s alone. Earlier, Connie Sachs had greeted Smiley with the comment, “I don’t know about you, George, but I feel seriously underfucked.” Smiley himself, of course, is estranged from his wife, who had the affair with Haydon. These are the anti-James Bonds. It’s lonely out there for a secret agent.

Ultimately we get our answer, we find our spy, but the murkiness never goes away. The mole is not Alleline, the obvious choice, but Haydon, the best friend. He seduced Smiley’s wife at Karla’s bequest so Smiley wouldn’t be able to see him clearly. Smart. “Witchcraft” is bullshit. MI6 was played to get to the Americans. Control suspected but the higher-ups, like the permanent undersecretary, liked Alleline’s results and believed what they wanted to believe. It’s the numbers game all over again.

“Tinker Tailor” is a well-made movie for smart audiences. It conjures up the dread, ominousness, and moral ambiguity of the Cold War. It gives us a great lead performance and one of the best acting ensembles in years. But it’s a tough movie to come to cold. I was lost for much of the movie (like Smiley, I suppose), pieced it together only at the end (again, like Smiley), but feel I missed out on all the subtleties in between. I’ll probably go again. It’s a movie worth seeing but probably more worth seeing twice.

Thursday December 15, 2011

Movie Review: Friends with Benefits (2011)

WARNING: REVIEW WITH SPOILERS

“Friends with Benefits” wants to comment upon the problem with romantic comedies while delivering a better romantic comedy. So Jamie (Mila Kunis) yells at a poster of recent rom-com queen Katherine Heigl, calling her a liar for the upbeat endings of her movies, but this movie still gives us an upbeat ending. So Dylan (Justin Timberlake) mocks the obviousness of the genre’s original soundtrack music when the indie-pop soundtrack of this film is equally obvious.

Those other rom-coms are fake, this rom-com is saying. We’re real.

But it’s not.

Dylan’s New York apartment alone pissed me off. He’s an LA dude, headhunted by Jamie for GQ magazine to be its art director in New York. When he shows up, there’s a new apartment waiting for him: spacious, impeccably designed, wide glass-door refrigerator, stunning view of the city.

Really? On an art director’s salary?

I happened to be watching this thing with a woman who was art director of Newsweek magazine from 1985 to 1995—back when, you know, magazines meant something—so I asked her. Did she live like that? Did she live close to that?

I happened to be watching this thing with a woman who was art director of Newsweek magazine from 1985 to 1995—back when, you know, magazines meant something—so I asked her. Did she live like that? Did she live close to that?

“You live that way in New York if you’re, like, a gazillionaire,” she said.

The beginning alone pissed me off. Not the beginning-beginning, when we see Dylan talking on his cell, late for a date, and we see Jamie talking on her cell, waiting for her date, and we think they’re talking to each other when really she’s waiting on Andy Samberg in New York, who’s about to break up with her, and he’s late for Emma Stone in LA, who’s about to break up with him. That was a good bit.

No, it’s when he flies to New York, headhunted by her, and she meets him at the airport, takes him to GQ, waits for him outside, takes him out for drinks, takes him to her secret spot in Manhattan—the roof of a building, which is her mountaintop, she says, her place of solitude—and then into the middle of a flash mob in Times Square, singing (for him?) “New York, New York.” After all that, he finally decides to take the job.

In other words, in the middle of a global financial meltdown, where most people are either underemployed or unemployed, we get to watch this little shit get wined and dined to take a high-paying job at a well-known publication in the most dynamic city in the world so he can live in this insane apartment where he gets to fuck Mila Kunis on a regular basis?

The early back-and-forth between Jamie and Dylan is awful. She’s from New York, see, so she’s blunt and a power walker, and he’s from LA, see, so he’s polite and waits for streetlights. She’s dynamic, he’s blank. Many things about her say “headhunter.” Not much about him says “art director.” It says “former boy-band member who’s a dynamic performer and can act a little but not well enough to make you believe he’s an art director for a magazine.”

They work out the deal—the friends-with-benefits deal—on the couch. Twenty years earlier, NBC aired an episode of “Seinfeld,” called “The Deal,” in which Jerry and Elaine worked out a FWB deal on the couch. They came up with a set of rules so they could have “this” (the friendship) as well as “that” (the sex). It was a funny episode. It felt true. And it lasted a half hour—twenty minutes with commercials. “Friends with Benefits” takes 90 minutes longer to deliver something much less funny and much less true.

Other characters show up about a half-hour in. Thank God. Jamie’s mom (Patricia Clarkson) is man-hungry and flakey. Dylan’s dad (Richard Jenkins) has early-stages Alzheimer’s and Dylan is often embarrassed by him—which he’ll overcome in a big way in the third act. Dylan has a nephew who does elaborate magic tricks that don’t quite work. Shaun White makes unnecessary cameos. It’s boy meets girl, boy fucks girl, boy befriends girl, boy insults girl, boy gets girl back in the final reel through his own flash mob singing the song he’s sung throughout the movie, “Closing Time” by Semisonic. I like that song (“Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end”) but here it helps Jamie and Dylan get together. Happily-ever-after is implied. It’s the movies, where every new beginning leads to the same effin' Hollywood end.

Friday December 09, 2011

Movie Review: Le Havre (2011)

WARNING: SPØILERS

Early in the French-Finnish film “Le Havre,” the main character, Marcel Marx (André Wilms), is sharing drinks with Yvette (Evelyne Didi ), the owner of “La Moderne,” a small neighborhood pub. He’s telling her about his wife, Arletty (Kati Outinen), who was recently diagnosed with cancer. It’s bad, this cancer, but Marcel doesn’t know that. Arletty convinced her doctor to tell him otherwise. So on this night, a free drink in hand, Marcel has some relief. “Benign,” he says of the cancer with a smile. “Completely benign.”

Those were my thoughts about “Le Havre.” The film is benign. Completely benign.

Too benign.

Marcel, a handsome man in his 60s, ekes out a living as a shoeshine in the French port city of Le Havre. As the film opens, people flood out at a subway stop and past two shoeshines, Marcel and Chang (Quoc Dung Nguyen), who look down at everyone’s shoes, hoping for the dress variety but generally getting the sloppy shoes most of us wear. Then a shifty-eyed man in a suit, with dress shoes and a briefcase handcuffed to his wrist, arrives. He stops to get a shoeshine from Marcel, less because he wants one than as a distraction against those who are pursuing him. Doesn’t work. They gather. He sees them here ... and there. When he bolts, they follow. Most movies would follow as well, since most movies are about such things; but Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki (“The Man Without a Past”) stays on the men who shine shoes. He stays with the down-but-not-quite-out in this port city equidistant between Paris and London.

Marcel, a handsome man in his 60s, ekes out a living as a shoeshine in the French port city of Le Havre. As the film opens, people flood out at a subway stop and past two shoeshines, Marcel and Chang (Quoc Dung Nguyen), who look down at everyone’s shoes, hoping for the dress variety but generally getting the sloppy shoes most of us wear. Then a shifty-eyed man in a suit, with dress shoes and a briefcase handcuffed to his wrist, arrives. He stops to get a shoeshine from Marcel, less because he wants one than as a distraction against those who are pursuing him. Doesn’t work. They gather. He sees them here ... and there. When he bolts, they follow. Most movies would follow as well, since most movies are about such things; but Finnish director Aki Kaurismäki (“The Man Without a Past”) stays on the men who shine shoes. He stays with the down-but-not-quite-out in this port city equidistant between Paris and London.

Marcel is a bit of rascal who steals bread, lets bills linger, but has the charm to get away with it. His wife awaits his return, then sends him off for an aperitif while she cooks, then shines his shoes while he sleeps. They keep what savings they have in a small tin box. The next day he does it again. It’s a hand-to-mouth existence, but, since this is France, what goes into the mouth is pretty good.

Meanwhile, a port nightwatchman making the rounds taps onto a large cargo container and hears a baby cry. Authorities are alerted, including Inspector Monet (Jean-Pierre Darroussin). They expect dead bodies but when the container is opened an entire west African family is nonchalantly living there, including Idrissa (Blondin Miguel), who, seeing his chance, stands, waits a bit, looks at an elder, who nods, then makes a dash, or a kind of half-jog to the front of the container, where he stops, confronted, or not, by three or four cops. They all stare at each other with blank expressions. Then Idrissa makes a dash, or a kind of half-jog, down a row of containers to safety. No one tries to stop him, although one cop pulls a gun and aims it before Inspector Monet tells him to put it away.

It’s a pivotal scene for content as much as tone. But what to make of the tone? Some might be amused by its purposeful inauthenticity. They might like the stiffness and amateurishness of it all. It might remind them of Wes Anderson x 10. Me, I saw little charm and less amusement.

These two characters, Idrissa and Marcel, cross paths, of course. As the newspapers splash scary headlines about the escaped youth, wondering if he has links to al Qaeda, Marcel shelters him. When the police close in, the neighborhood shelters Marcel. When $3,000 is needed to smuggle the kid to London, where his mother works in a Chinese laundry, Marcel convinces local rock star, and homunculus, “Little Bob” (Roberto Piazza), to throw a charity concert. The rest of the money Marcel pulls from the small tin box. When Inspector Monet figures out everything, he, too, turns out to be benign, and misdirects the other cops to allow Idrissa’s escape. The world’s a nice place. The common people—except for a nasty neighbor—stick together.

All of these good deeds do not go unrewarded, either. Yvette makes a recovery that astounds her doctors and returns home with Marcel. “Look Marcel,” she says. “The cherry tree blooms. I’ll make dinner right away.” The End.

“Le Havre” made me laugh a few times. I like the names, the homage, Kaurismäki chose for his characters. Marcel for Marceau or Carne? Marx for Groucho, Harpo or Karl? Arletty obviously for the great French actress. Yvette for Mimeux? Even Marcel’s dog, Laika, is named for the Russian dog who was shot into space in the 1950s, and whom Ingemar eulogizes throughout Lase Hallstrom’s great film, “My Life as a Dog.”

But the film does nothing for me. It feels fake in tone and fake in content and fake in lesson. What’s the point of it? It’s been called “Keatonesque,” after Buster, but Keaton was the deadpan comedian amid great turmoil, which he often unknowingly caused. Here, Marcel is the lively character, the charmer, amid a deadpan world. Can you celebrate life by staring at it blankly? I think not, but Kaurismäki seems to think so.

Fans of “The Man Without a Past” should know: I didn’t like that one, an Academy Award nominee for best foreign language film, either.

Thursday December 01, 2011

Movie Review: Take Shelter (2011)

WARNING: There are SPOILERS coming—the likes of which none of us have ever SEEN!

Why not “Shelter”? Why not “Storm”? Isn’t that more direct? What do you get when you add that clunky verb to the title?

You get the imperative. You get a warning. But who’s giving the warning, who’s receiving it, and what are we being warned about?

Curtis (Michael Shannon) is a blue-collar worker in Elyria, Ohio, with a beautiful wife, Samantha (Jessica Chastain), and a three-year-old, deaf daughter named Hannah (Tova Stewart). For a Michael Shannon character, he's fairly normal. We see him sign “I love you” to her in the morning. We see him come home late at night and stand by her bedroom door as she sleeps. “I still take off my boots to not wake her,” he tells his wife when she comes up and puts her arms around him. Life is still a struggle. Samantha sews to make extra money. Hannah isn’t playing with other children. But it’s not bad. “You got a good life, Curtis,” his friend and co-worker Dewart (Shea Whigham, a fellow “Boardwalk Empire” actor) tells him. “I think that’s the best compliment you can give a man.”

Curtis (Michael Shannon) is a blue-collar worker in Elyria, Ohio, with a beautiful wife, Samantha (Jessica Chastain), and a three-year-old, deaf daughter named Hannah (Tova Stewart). For a Michael Shannon character, he's fairly normal. We see him sign “I love you” to her in the morning. We see him come home late at night and stand by her bedroom door as she sleeps. “I still take off my boots to not wake her,” he tells his wife when she comes up and puts her arms around him. Life is still a struggle. Samantha sews to make extra money. Hannah isn’t playing with other children. But it’s not bad. “You got a good life, Curtis,” his friend and co-worker Dewart (Shea Whigham, a fellow “Boardwalk Empire” actor) tells him. “I think that’s the best compliment you can give a man.”

Then Curtis begins to have bad dreams.

The dreams take the same form. A storm is coming and it begins to rain. But it’s not water—it has the consistency of motor oil—and Hannah is imperiled and/or Curtis is attacked. In one dream his dog gets him. In another, it’s Dewart. People attack them in their car and carry Hannah away. They attack them in their home and all of the furniture levitates. One morning, he wakes in a sweat. Another, he wets the bed. He hides all of this from his wife. She assumes he has a cold.

He begins to act badly. His dog has always been a beloved indoor dog but now Curtis sets up a small wire-mesh fence around the doghouse outside and sticks him there. “Sorry about this, buddy,” he says. He opens up the old storm shelter in the backyard, goes inside and breathes as if he's home. At the library he checks out books on mental illness—his mother first suffered from paranoid schizophrenia in her 30s, and he’s now 35—but on the way home he buys huge quantities of canned goods.

He keeps doing this kind of left hand/right hand thing. He seems to realize his paranoia is a consequence of his mental illness, and sees a therapist, and takes pills, etc., to be cured of it; but he still acts on the paranoia. Things must be done to get ready. So he and Dewart borrow equipment from work to dig a huge hole in the backyard to expand the shelter. He takes out a risky bank loan to pay for the expansion. “Are you out of your mind?” his wife asks.

Initially, the sleeping pills help. He wakes up, no bad dreams, white curtains billowing. But he’s merely chased the bad dreams into daylight. At work, under blue skies, he hears thunder that Dewart doesn’t. Driving home from a sign-language class, wife and daughter asleep in the back, he stops the car on the side of the road and watches a lightning storm light up the horizon. “Is anyone seeing this?” he wonders.

Just him.

We assume the problem is compounded by his lack of communication. “If only he’d talk to his wife,” we think. He does and it doesn’t help.

When he isolates himself from anyone he dreams about—giving away his dog to his elder brother, talking the boss into taking Dewart off his crew—we wonder what would happen if he dreams about Samantha. Then he does. That morning he flinches away from her touch. A second later, he sees the boss in the backyard, looking over his expanded storm shelter, and panics. Samantha had managed to get their daughter an operation for a cochlear implant, and when she’s told that her husband’s insurance will pay for most of it, that he’s got good insurance, it’s like a rumbling of thunder in the distance. We know he’ll lose it. And he does. The operation is still five weeks away when the boss shows up, alerted by Dewart over the equipment “loan,” and fires him. There’s a great economical scene when Curtis drags himself back into the kitchen, where his wife is doing dishes. “I’ve been fired,” he says. She stops, doesn’t look at him, her back up. “What about the health insurance?” she asks. “I got two more weeks,” he answers. She walks up to him, slaps his face, takes their daughter on her hip, opens the side door, opens the screen door, leaves. The choreography alone recommends the scene.

At this point in the movie, we have two possibilities: Curtis is right and vindicated or he’s wrong and nuts. Generally, I'm not a fan of either/or movies.

This sense of limited choices is crystallized—gloriously, I should add—when Samantha insists they go to a Grange Hall function and eat lunch with their neighbors. They get nods, smiles, paper plates with chicken and baked beans. But Dewart is there, still angry over the betrayal, and he starts a fight with Curtis. But it’s Curtis, tall and lanky, who ends it with a kick, then stands and upends their long, fold-up table. And suddenly he's shouting at his neighbors like a Pentecostal preacher:

There’s a STORM coming! The likes of which none of us have ever SEEN! And not a one of us is prepared for it yet!

Up to this point, Curtis has been bottled up, and we’ve been bottled up with him, so the outburst itself is like a long-delayed storm. If he’s told anyone about his dreams, he’s mentioned them in mumbles, embarrassed, full of doubt. In this scene, doubt is removed. He sounds like a prophet. Or a crazy man. We wait to find out which.

We don’t wait long. That night he has another bad dream ... until Samantha wakes him because a real storm is bearing down on them. They grab their daughter and make for the shelter, where, inside, they huddle wearing gas masks and oxygen tanks, expecting the worst. After sleeping, their opinions diverge. Should they go outside? “What if it’s not over?” he asks, doom in his voice.

Oddly, I began to flash to a bad 1999 comedy, “Blast from the Past,” in which Christopher Walken plays a man in the early 1960s so paranoid about the Cold War that he builds an extensive bomb shelter in his backyard, down which he takes his family during the Cuban Missile crisis. They live there for 35 years. I’ve long thought that Shannon should play Walken’s son in a movie—there’s not only a physical resemblance but both men play determinedly off-kilter roles—and he does, in a sense, in this one. Thankfully, it’s in a better movie. It’s also a stunning performance by Shannon, who’s getting Oscar buzz.

But again, we're down to an either/or proposition. Either they stay in the shelter forever, perhaps even die there, or they go outside where the world is either ruined or being cleaned up after a nasty summer storm. It takes cajoling from Samantha to get them out. “This is what it means to stay with us,” she tells him. “This is something you have to do.” So he does. He opens the storm doors, shutting his eyes tightly on his imagined apocalypse ... only to open them on neighbors and workers cleaning up fallen branches and power lines after a bad summer storm.

Sitting in the audience, I was reminded of all the hand-wringing and apocalyptic-warnings of the U.S. after 9/11. What do you do with the thing you fear the most? Do you let it control you—this thing you can’t control? Do you take the family into the storm shelter, real or metaphorical, and hole up there? Or do you live your life? Most movies, and not just horror movies, teach us to fear, and “Take Shelter,” I felt, was teaching us the opposite. Its message was Rooseveltian: It was our fear we needed to fear. It took a tortured path, through an atmospheric, often painful movie, to this realization. But realization came.

Then it went. Curtis sees a psychiatrist, not just a therapist, who recommends distance from the storm shelter, the thing Curtis thinks will keep him safe. So off they go to the beach. What beach? I assume along Lake Erie. There, Curtis and his daughter build sand castles, those careful constructions designed to get wiped away, and he seems to be enjoying himself. Then Hannah points toward the water. He’s slow to respond, but when he does it’s with a mixture of shock and recognition and vindication, and he slowly stands; and in their beach house, Samantha sees it, too, and goes outside as the rain begins. But it’s not rain. She rubs the dirty substance between her fingers, as Curtis did in his dreams, and he looks back as if to say, “See?” She nods. She knows now. And only then does writer-director Jeff Nichols pull back so we can see what they see: a huge storm over Lake Erie, with multiple tornadoes bearing down on them, the likes of which none of us have ever seen.

That’s the end. That’s the image we take with us from the theater.

Afterwards, the four of us—Patricia, Vinnie, Laura and I—had dinner in Wallingford and talked about the movie. Vinnie couldn’t abide the new ending; he wanted the old ending. He only perked up slightly when I mentioned that the new ending could still be a dream, Curtis’ dream, or maybe even Samantha’s. Maybe she was in on it with him now. But that hardly resonates, does it? To me, if the ending is a dream, it makes the movie worse.

But what to make of the new ending? Curtis, instead of being a loon, a mild schizophrenic, is in fact a prophet; and the movie, instead of a mild warning against fear, is a stern warning to fear. The title, in this respect, could be part of that warning. “Take Shelter” isn’t just what Curtis does, it’s what Nichols is telling us to do. He’s telling us a storm is coming the likes of which none of us have ever seen. One assumes he’s talking about global warming/climate change. You could argue that “Take Shelter” is the most powerful movie about climate change ever made because it isn’t about climate change until the very end. Until it’s too late. “Is anyone seeing this?” Indeed.

Unless you choose to see the storm as a metaphor. In which case it could be about ... anything: corporations, terrorism, Sarah Palin, Barack Obama. Prophets of the world unite! The only thing we have to fear is... the end of everything we know and love. And it’s right around the corner.

Tuesday November 29, 2011

Movie Review: The Descendants (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Everyone says that comedy is tragedy plus time, but in “The Descendants” writer-director Alexander Payne removes time from the equation. A woman—a mother, wife and daughter—is dying in a hospital bed, having spent the last year of her life cheating on her husband, and we find ourselves laughing out loud. Payne creates comedy out of tragedy as it’s happening.

Fifteen minutes in, I admit, I thought Payne was flubbing it. I thought the critics who were touting “The Descendants” as a best picture contender had blown it. Then the movie began to work and didn’t stop.

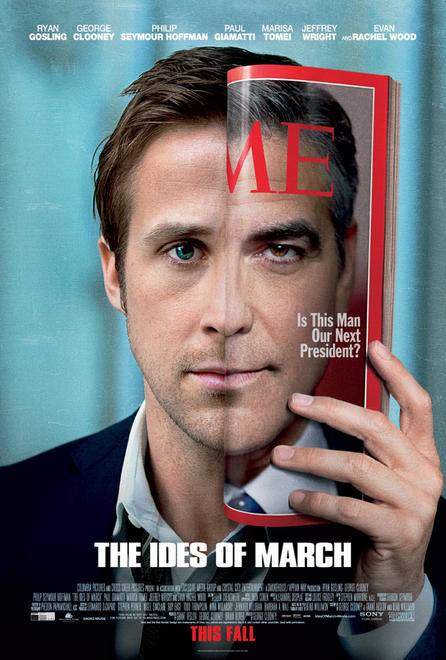

Matt King (George Clooney) is a self-professed “back-up parent” in Hawaii who suddenly has his hands full when his wife, Liz (Patricia Hastie), suffers a head injury during a boating accident and goes into a coma. Meanwhile, his 10-year-old daughter, Scottie (Amara Miller), is sending nasty text messages to friends. When he goes to retrieve his 17-year-old daughter, Alexandra (Shailene Woodley), from the Hawaii Pacific Institute, a kind of summer reform school, he finds her drunk and playing midnight golf and unsympathetic about mom in the hospital. “Fuck mom!” she shouts.

Matt King (George Clooney) is a self-professed “back-up parent” in Hawaii who suddenly has his hands full when his wife, Liz (Patricia Hastie), suffers a head injury during a boating accident and goes into a coma. Meanwhile, his 10-year-old daughter, Scottie (Amara Miller), is sending nasty text messages to friends. When he goes to retrieve his 17-year-old daughter, Alexandra (Shailene Woodley), from the Hawaii Pacific Institute, a kind of summer reform school, he finds her drunk and playing midnight golf and unsympathetic about mom in the hospital. “Fuck mom!” she shouts.

At which point, Matt, in voice-over, wonders how he always winds up with such self-destructive women.

If there’s an oddity to the movie—beyond the removal of time from the comedy/tragedy equation—it’s that almost everyone seems to think Liz will wake from her coma. After 21 days of nothing, they all seem to assume she’ll be fine. The guy who was driving the boat when she had the accident, Troy (surf champ Laird Hamilton in a surprise, low-key cameo), says he visited her, prayed with her, and saw her hand move. Her best friend Kai Mitchell (Mary Birdsong) puts make-up on her. Both children act as bratty as ever, as if mom is simply on vacation.

By this point, though, Matt knows Liz won’t wake up, and, per her living will, she will soon be taken off life support, and it’s up to him to break the news to everyone. The first person he tells is his 17-year-old, Alex, who is too busy talking on her cell and complaining about the leaves in the backyard pool to listen to him. So he tells her while she’s gliding along in the pool. For a second, she looks stunned; then she dives beneath the surface and her face crumples and she swims powerful strokes as if to get away from the bad news. When she surfaces she’s gone maybe five feet. “Why did you tell me in the goddamned pool!” she cries. It’s a great scene with a great actress. Who is this? I thought.

Matt screws up the second telling, too. Alexandra has just given him tit for tat—her bad news for his. “You really don’t have a clue, do you?” she asks, then drops the news that will propel the rest of the movie: “Dad, Mom was cheating on you—that’s what we fought about.” The family lives in Hawaii, and Clooney spends most of the movie in baggy shorts and shirts and sandals. Even his face has a kind of bagginess to it. He’s still movie-star handsome but there’s a layer of puffiness there that you won’t find in “Ocean’s Eleven” but probably see every morning in the mirror. After Alex drops her news bomb, Matt, in a kind of daze, struggles to put on his sandals, then does a kind of run/shuffle for blocks. It’s quite funny, but so inappropriate that one doesn’t feel like laughing. Yet. Is he, like Alexandra, simply running away from bad news? Is he running to the house of the man who cuckolded him? Neither. He winds up at the Mitchells, Kai and Mark (Rob Huebel), who are in the midst of their own absurd argument about cocktails (nice touch) to find out what they know about the affair. Turns out they know it all. Kai continues to defend Liz, how she was lonely, etc., but Matt isn’t having it, and he angrily breaks the news. “You were putting lipstick on a corpse!” he shouts, which causes Kai to break down. Something about her crying, as with his running, tickles us, and, though it was still quite inappropriate, I burst out laughing. The gates were open—for both Matt and me. He was free to find out about his wife’s lover and I was free to laugh.

Good thing. The movie keeps getting funnier. It also gets more poignant.

Matt has three tasks: 1) to find his wife’s lover, Brian Speer (Matthew Lillard); 2) to tell Liz’s loved ones that she’s dying so they can say their good-byes; and 3) and to preside over the sale of a huge tract of undeveloped land that his family has owned for generations. The buyers are either a Chicago developer, who put in the highest bid, or a Hawaiian developer, who will keep the money in Hawaii. Various cousins in baggy shorts, shirts, and flip-flops, all of whom will come into millions, as will Matt, have their say—including Beau Bridges as Cousin Hugh, seemingly channeling his brother Jeff’s Dude. Some of the cousins don’t want to sell at all.

Of these three tasks, the third task provides some background on Hawaiian history, and gives us some spectacular shots of undeveloped coastal land, but it’s not particularly intriguing. The second task is a tough one, and poignant, and will resonate with most moviegoers, but dramatically it’s a dead end. It’s the first task that drives the movie.

When Alexandra questions why he’s seeking his wife’s lover, Matt merely seems confused. “I just want to see his face,” he says at one point. To punch him? To tell him the bad news so he can say his good-byes as well? Matt doesn’t know himself, so the movie doesn’t know, so we don’t know. What will happen when they meet? Will it feel true? Will it resonate? Can it do both? The possibilities aren’t multiple choice and the impulse is universal because Matt doesn’t know what drives him.

On this task and others, Alex insists upon coming along, which means Scottie has to come along. The fourth member of their group, or troupe, as in a comedy, is Alex’s friend Sid (Nick Krause), a laid-back dude, part-stoner, part-stupid, with a blissed-out face and a wide smile. When he first meets Matt, he hugs him.

Sid (smiling): What’s up, bro?

Matt (not): Don’t ever do that again.

When Matt breaks the bad news to Liz’s father, Scott (Robert Forster), Sid doesn’t know enough to stay in the background. The mother, Alice (Barbara L. Southern), teeters out, and it’s apparent she’s not all there. Alzheimer’s, one assumes. She doesn’t know her son-in-law, she doesn’t know her grandchildren. When Scott talks about visiting Elizabeth in the hospital, she thinks he’s talking about Queen Elizabeth and gets excited, causing Sid to laugh out loud. Confronted, Sid compounds his error by continuing to smile and insisting that Alice must be joking. Right? “I’m going to hit you,” Scott says matter-of-factly, and then: Pow! Next scene, Sid isn’t smiling. More laughter.

But there’s redemption in “The Descendants,” too. On another island, in pursuit of Scott Speer, Matt can’t sleep, Sid can’t sleep, and they have a midnight talk in the living room. Sid insists he’s smarter than Matt realizes. “You are about a hundred miles from smart,” Matt answers. But as the talk deepens, we learn, with Matt, that Sid’s father recently died. At first, Sid says this with a shrug that attempts nonchalance. Then he owns up. “November 24th,” he says. “Drunk driver. Actually, both drivers were drunk.” Up to this point, Sid has been a picked-upon figure, comic relief, yet he’s never used his own recent tragedy as a means to sympathy, or as a kind of justification for boorish behavior (“Hey, my own dad died, too!”), or as a way to muscle in on the Kings’ tragedy. He allows their tragedy to be itself. He may not be smart, but he’s something.

So is Scott. In the hospital room, he lambastes his son-in-law for his stinginess. (In an earlier scene, Matt, in voiceover, mentions that he, like his father, never spent what he didn’t make himself. “Give your children enough to do something,” he says, “but not enough to do nothing.”) Scott thinks if Matt had just bought Liz a better boat, she’d be alive. He’s angry about it. He calls Matt names, and calls Liz a faithful, devoted wife who deserved more, and for a moment Matt rises up, about to shatter his father-in-law’s illusions. The he calms down and says, “Yes, she deserved more,” and leads the kids out into the hallway, where Sid says, “That guy is such a prick! Was he always like that?” Even as Matt admits as much, he sees, and we see, through the door, Scott, burdened with a wife with Alzheimer’s, saying good-bye forever to his beloved daughter. A prick, yes, but a loving man who is losing everything. We all have that which humanizes us.

Does Brian Speer? That’s the question for most of the movie. Liz, in love, wanted to leave Matt for Brian. Is he the “more” she deserved?

Information comes in pieces. Matt discovers Brian is renting a cottage from one of his cousins. Then he discovers Matt has a wife, Julie (Judy Greer), and two boys. Then he discovers that when the sale on the undeveloped land goes through, Brian, brother-in-law to the Hawaiian developer, will make millions selling it for him.

Is that why Brian was sleeping with Liz? To get close to Matt and his deal?

Matt doesn’t find out until he gets close to Brian, on the cottage porch, where he tells him, “Elizabeth is dying. Oh yeah: Fuck you.”

Inside, they have this nice exchange:

Brian: It just happened.

Matt: Nothing just happens.

Brian: Everything just happens.

He wasn’t using her to get to Matt. But did he love her? When Matt asks him directly, Brian hesitates; and in that hesitation Matt has his answer. Brian was never going to leave his wife and family for Liz. He was just fucking her. It’s an answer 100 times sadder than if he’d broken down and cried. It speaks to Liz’s self-delusion and loneliness. Later, when Matt agrees with Scott that Liz deserved more, he means not just more than himself but more than Brian Speer.

The news also allows Matt to find it in himself forgive Liz.

Three times during the movie he speaks to her comatose figure . The first time it’s practical and family-related. “Please, Liz, just wake up,” he says, his hands full with girls he can’t control. “I’m ready to be a real husband and father.”

The second time, after he finds out about the affair, he lets loose his anger. “Who are you?” he shouts. “The only thing I know for sure is you’re a goddamned liar!”

The final time, after this bargaining and anger (mixed with denial and depression), we get acceptance. We get forgiveness and love. He kisses her parched lips. “Good-bye Elizabeth,” he says. “My love, my friend, my pain, my joy. Good-bye, good-bye, good-bye.”

We think that’s the ending—and it would be a good ending—but we continue on to a scene where Matt and his two girls silently release Elizabeth’s ashes into a Hawaiian bay, possibly where the accident occurred, then place leis on the water, which we see from below.

We think that’s the ending—and it would’ve been a good ending—but we get another scene. Scottie’s on the couch watching “March of the Penguins,” narrated by Morgan Freeman. Matt joins her with two bowls of ice cream, strawberry and mocha chip. They share a blanket. Is it the same blanket Liz used in the hospital? Alex joins them, and, without smiles, with eyes fixed on the TV, all three share bowls of ice cream and the blanket. Earlier in the movie, Matt compared a family to a Hawaiian archipelago: connected, but separate, and forever drifting apart. Here, for an ordinary moment anyway, we see them together. We think that’s the ending, and it is, and it’s a good ending.

What I’ve relayed isn’t exactly funny but the movie is. The script helps. The character of Sid helps. The character of Scottie, creating her “sand boobs” helps. George Clooney helps. A bit too much? At times, he plays it a bit “O Brother, Where Art Thou?”—as in this scene where he first spots Brian’s cottage:

Shailene Woodley, who isn’t funny, is a revelation. There’s not a false note in her performance. Is there buzz for a supporting actress nom? One hopes.

As for the land deal? Matt, as sole trustee, ultimately nixes it, screwing over Brian Speer, but one wonders if it’s a necessary subplot. You could cut out the whole thing and the main storyline wouldn’t change. At the same time, you’d lose something ineffable. Part of it is Hawaiian history, as I said, and part of it is the movie’s title. But it’s more. Yes, these are the descendants, this King and his two girls, and all of their cousins; and they’ve been entrusted with this great wealth; and the question is what they do with it. Most of us aren’t going to come into millions, like the Kings, but the dynamic, the dilemma, the perspective, still resonates, because it’s universal. All of us are descendants. All of us are entrusted with this great wealth—the wealth of the world. And the question is what we do with it.

Wednesday November 23, 2011

Movie Review: Hugo (2011)

WARNING: CLANDESTINE SPOILERS

For most of its 50-year history, 3-D movies have been famous, or infamous, for propelling cinematic objects at its audience. Martin Scorsese turns this idea on its head. He begins “Hugo,” his first 3-D movie, as well as his first children’s movie, by propelling his audience at cinematic objects.

We begin with an extended shot inside of the Montparnasse train station in the 14th arrondissement of Paris in 1931. It’s crowded, as train stations are, but the camera keeps moving through hordes of people getting on and off the train. If the tendency in a traditional 3-D movie is to duck out of the way of thrown objects, the tendency here is to bob and weave through the crowd. It puts us in the scene. It feels like magic.

Magic is key to “Hugo” and—Scorsese would argue—to cinema. Maybe we don’t always feel it now. Maybe we’re all a little too jaded in the 21st century with our iPhones and iPads. So Scorsese takes us back to a time when we didn’t need 3-D technology to flinch away from something onscreen—we did it anyway, in 1895, with the black-and-white, 48-second film “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat” by the Lumiere Brothers. He reminds us that movies were not only magic but created by magicians; that books were once precious, and thus magic when in your hands; and that being whole in body and spirit after the Great War and during the Great Depression was so rare it was a kind of magic, too.

Magic is key to “Hugo” and—Scorsese would argue—to cinema. Maybe we don’t always feel it now. Maybe we’re all a little too jaded in the 21st century with our iPhones and iPads. So Scorsese takes us back to a time when we didn’t need 3-D technology to flinch away from something onscreen—we did it anyway, in 1895, with the black-and-white, 48-second film “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat” by the Lumiere Brothers. He reminds us that movies were not only magic but created by magicians; that books were once precious, and thus magic when in your hands; and that being whole in body and spirit after the Great War and during the Great Depression was so rare it was a kind of magic, too.

(Remember that train arrival, by the way. It returns.)

“Hugo,” I should mention at the outset, is completely charming, hugely entertaining, and genuinely educational. Almost everyone who sees it will be educated. Even I, at 48, was educated.

The title character, Hugo Cabret (Asa Butterfield), is a 10-year-old orphan who lives inside the clockwork at the Montparnasse train station. He life is both dodgy and an adventure: He steals to eat, steals equipment to fix the clocks, and is forever on the run from the Station Inspector (Sacha Baron Cohen) and his growling Doberman Pinscher. We can’t help but wonder how he got there. And why he stays there.

From behind the clocks at the station, he peers, generally out the number “4,” at the goings-on of the station: the attempts of Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) to woo Madame Emille (Frances de la Tour); the attempts of the Station Inspector, with his squeaky metal leg, to merely speak to Lisette, the flower girl (Emily Mortimer), or to capture another urchin and send him off to the orphanage. He sees the monumental Monsieur Labisse (Christopher Lee) sitting inside his book shop and the quiet Georges Méliès (Ben Kingsley) dozing in front of his toy/repair shop with a tool nearby. Which is when he makes his move.

Bad move. Méliès was merely laying a trap for him, this boy, this THIEF, who had already stolen half of Méliès’ tool collection. He demands that he empty his pockets. But Hugo’s pockets merely contain bits and pieces: flotsam. Plus a notebook with words and diagrams and drawings. When Méliès sees it he gasps in recognition before turning even frostier. Hugo pleads with him to give it back but the next day Méliès shows up with ashes wrapped in a handkerchief.

The notebook, which isn’t really destroyed, is one of the few mementoes Hugo has of his father (Jude Law), a clock keeper and repairman. In a brief flashback, we see the father buy an automaton from a museum and attempt to fix it—to bring it back to life. Then he dies in a sudden fire and Hugo is adopted by his drunk Uncle Claude (Ray Winstone); he is taken to the Montparnasse station and put to work. Then Claude, too, disappears. (He drowns, we find out later, in the Seine.) But Hugo keeps working. He keeps all the clocks going so no one will investigate, find him alone, and put him in an orphanage. You could say he’s a boy trapped in time.

After the scene with the ashes, Hugo’s spirit is revived by Méliès’s goddaughter, Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz), another orphan, but a happy one with a home. She’s a precocious lover of books and words (“clan-des-tine”), who talks up fantasy worlds such as Oz, Neverland, and Treasure Island. But she wants an adventure of her own and she sees Hugo as the key. One day he offers her one: He takes her to the movies. Specifically, he sneaks her into the movies.

Isabelle: We could get into trouble...

Hugo: That’s how you know it’s an adventure.

Before they’re tossed out, they see Harold Lloyd dangling from a clock tower in “Safety Last,” an indelible cinematic image, and one Hugo will repeat before the movie is over. Afterwards, she tells him Papa Georges doesn’t allow her to go to movies, though she’s not sure why, and he tells her how his father loved movies, and once saw a film where a rocketship went right into the eye of the moon. The father said it was like seeing his dreams in the middle of the day.

Their adventure, and friendship, deepens, and he show her where he lives. “I feel like Jean Val Jean,” she says, of the steamy metal works, where, behind the scenes, Hugo has been attempting to do what his father couldn’t: fix, or bring to life, the automaton. He believes if he fixes it, he will receive a message from his father. One thing stands in his way: a keyhole in the shape of a heart.

Somehow Isabelle has that key.

The automaton is poised to write, and, wound up, that’s what it does. Unfortunately what it writes is gobbledygook: a “c,” a “4,” an “r.” When it stops, it’s Hugo who breaks down. He cries and confesses that in his heart he thought if he fixed the automaton his father would come back to life.

Which is when the automaton begins writing again, faster and faster, and it becomes apparent that it’s not writing at all. It’s, as Hugo says, drawring. What does it drawr? A rocketship in the eye of the moon.

This does seem like a message from Hugo’s father. But at the last instant, the automaton adds a final touch—a name: Georges Méliès.

I assume a few people in the audience will know the answer to this mystery. They’ll know that Georges Méliès, a former magician, was an early innovator of cinema who created hundreds of films in the 1900s and 1910s, including “Le voyage dans la lune,” with the rocketship in the eye of the moon. He also created the automaton. Those who don’t know his cinematic background will enjoy uncovering the mystery along with Hugo and Isabelle, who are schooled by Prof. Rene Tabard (Michael Stuhlbarg), an early film historian, and all three will attempt to reunite the volatile Méliès with his past—to fix him, in Hugo’s words—all the while outrunning and outsmarting the Station Inspector and his Doberman Pinscher.

That’s basically the rest of the movie and you can guess how it goes. “Happy endings only happen in the movies,” Hugo says earlier. And he’s right. At least here.

I could go on. The art and set direction of “Hugo” are incredible—those great puffs of steam behind the works—and the acting is wonderful: from big people with small roles to small people with big roles. Chloë Grace Moretz makes anew the smart girl with the precocious vocabulary, and Asa Butterfield, with his intense blue eyes, wears pain the way other actors wear a scarf. You feel, even in happy moments, it never quite leaves him. Sacha Baron Cohen, meanwhile, gives us a villain who is actually sympathetic (and still comic), while Michael Stuhlbarg brings his innate gentleness, previously cloaked in a schlemiel (“A Serious Man”) and a gangster (HBO’s “Boardwalk Empire”), to a true gentle man.

Even the source material is rich. “Hugo” is based upon the 2007 children’s book “The Invention of Hugo Cabret” by Brian Selznick. Initially I wondered if all the movie history was in the book, or if Scorsese, with his love of film and film history, added it. But it’s not only in the book, it's in the author. Brian Selznick, born in 1966, is first cousin twice removed to David O. Selznick, the producer of “Gone with the Wind.”

All of which is fascinating. But what I want to talk about is Hugo’s dream.

After the above scene with Isabelle and the automaton, Hugo sees Isabelle’s heart-shaped key on the train tracks in the station. He looks up, he looks down, then leaps onto the tracks. He fingers the key. He sees it as the answer. But at that moment a train is arriving and Hugo, lost in thought, doesn’t see it coming until it’s too late, until the train leaps the tracks and careens through the station and bursts through a wall and falls onto the ground outside, a story below. Which is when Hugo wakes up.

As he’s feeling himself to make sure he’s all there, he begins to change. His flesh becomes metal, and his torso becomes ribs of metal, and his face turns into the calm, expressionless (but somehow very expressive) face of the automaton. Which is when he wakes up again. A dream within a dream.

Each dream takes less than a minute but initially I felt a little cheated—as I often do with dreams in movies. But I gave this one a pass. I remembered the line “Movies are like dreams in the middle of the day” and thought this scene was building on that theme.

It was. And more.

Later in the film, at its climax, Hugo is taking the automaton to Georges Méliès but is finally caught by the Station Inspector; and in their struggle, the automaton goes flying in the air and lands on the train tracks... just as a train is coming. As the automaton is the key to everything, Hugo leaps onto the tracks to save it. But this is where his courage leaves him. He embraces the automaton but can’t move. He’s as frozen as the automaton. It’s up to the Station Inspector, acting as deus ex machina, the redemptive engine of himself, to pull both boy and robot to safety.

You think back to the dreams: The key is on the tracks; the boy and automaton are one.

But there’s more. Remember the Lumiere Brothers’ “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat,” which Hugo and Isabelle see while researching early film history? The people cowering from the oncoming train on the movie screen? That’s like this scene. That’s like his dream. The train on the screen leaps into Hugo’s dreams and reality.

But it wasn’t until I got home and researched the Gare Montparnasse that I found the true coup de grace. Because in 1895, the same year as “Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat,” a train did jump the tracks at the Gare Montparnasse; and it did careen through the station and burst through a wall and fall onto the ground outside, a story below. There’s a famous photograph showing that fallen train.

This is deep resonance. We get echoes upon echoes, involving dreams, history, film, and film history. The movie keeps doing this, too: the ashes of Hugo’s notebook; the ashes his father came to; the ashes Méliès’ early films were reduced to. On and on. The movie resonates so much it has a beat, a pulse. It’s alive.

Monday November 21, 2011

Movie Review: Transformers: Dark of the Moon (2011)

WARNING: SPOILERS

Saying “Transformers 3” isn’t as bad as “Transformers 2” is like saying the cold that put you in bed for a week wasn’t as bad as the pneumonia that put you in bed for a month. You still wouldn’t want to wish either on a friend.

“Transformers” movies have dominated the box office for four years now. The first, in 2007, grossed $319 million domestic and $709 worldwide. The second grossed $402 million domestic and $836 worldwide. This one grossed $369 million domestic and $1.12 billion worldwide. It’s hard for me to type sadder numbers.

Let’s step back a moment. What are we talking about with these movies? What are they about?

They’re about mechanical creatures, some giant, some small, who can transform into any mechanical thing on Earth: semi-truck, flat-screen TV, whatever. The good ones (Autobots) want to protect Earth; the bad ones (Decepticons) want to take it over. A few people, led by everyman Sam Witwicky (Shia LaBeouf), attempt to help the Autobots.

What else?

In each movie, Witwicky has an insanely hot girlfriend: Megan Fox in the first two movies, supermodel Rose Huntington-Whiteley in this one.  It’s the unlikeliest of matches, particularly if like lightning it strikes twice, but then none of the movie is logical. The hot women are there to draw more of the teen-boy crowd, or more of the boy-man crowd, who like to look at giant robots battling and pretty women pouting. In this one, Carla (Huntington-Whiteley) first shows up, filmed from behind, wearing panties and a man’s dress shirt like in that 1980s Brut cologne commercial. (“Honey, I was just thinking about you.”) Director Michael Bay gets even less subtle in a scene where Witwicky meets Carla’s boss, Dylan Gould (Patrick Dempsey), a rich, handsome somethingorother, who will become the movie’s chief villain, in league with the Decepticons. Dylan is showing off one of his vintage automobiles to Witwicky and commenting upon its curves, which he calls sensual. In a typical scene, Dylan would look Carla up and down as he did this. That would be the asshole thing to do. Here Bay does it himself. While Dylan talks, Bay’s camera pans up Huntington-Whiteley’s body. Making Bay the asshole? Making the audience the asshole? I wish it were a comment on our loutishness but it’s just another example of our loutishness—or Bay’s. Why not an up-the-skirt shot while he’s at it? Or is he saving that for “Transformers 4”?

It’s the unlikeliest of matches, particularly if like lightning it strikes twice, but then none of the movie is logical. The hot women are there to draw more of the teen-boy crowd, or more of the boy-man crowd, who like to look at giant robots battling and pretty women pouting. In this one, Carla (Huntington-Whiteley) first shows up, filmed from behind, wearing panties and a man’s dress shirt like in that 1980s Brut cologne commercial. (“Honey, I was just thinking about you.”) Director Michael Bay gets even less subtle in a scene where Witwicky meets Carla’s boss, Dylan Gould (Patrick Dempsey), a rich, handsome somethingorother, who will become the movie’s chief villain, in league with the Decepticons. Dylan is showing off one of his vintage automobiles to Witwicky and commenting upon its curves, which he calls sensual. In a typical scene, Dylan would look Carla up and down as he did this. That would be the asshole thing to do. Here Bay does it himself. While Dylan talks, Bay’s camera pans up Huntington-Whiteley’s body. Making Bay the asshole? Making the audience the asshole? I wish it were a comment on our loutishness but it’s just another example of our loutishness—or Bay’s. Why not an up-the-skirt shot while he’s at it? Or is he saving that for “Transformers 4”?

What else?

The giant robots are from a distant planet in a distant time, but on Earth, they’ve adopted well to not only 20th and 21st century technology (cars; flat-screen TVs) but 20th and 21st century pop culture. Some speak with British accents, some with Scottish brogues, some trash talk American-style. They know “Star Trek,” “We are Family” and “Missed it by that much.” The comic relief ones anyway. The main transformer, Optimus Prime, has a bland, stentorian voice, pronouncing the blandest of sentiments (“It is I, Optimus Prime!”) as if he were the hero of a 1950s television show, or, more to the point, a voice a kid might imagine when playing with his toys.

Because that’s what these things are: toys. Before he became a right-wing nutjob, Michael Medved wrote a book called “The Golden Turkey Awards,” in which he gave out awards, Golden Turkeys, to the worst of the worst in movie history—Worst actor, Richard Burton, for example—but my favorite Golden Turkey was for worst credit line. In an early, silent version of Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew” we got this credit line: “Additional dialogue by Sam Taylor.” To which Medved wondered: Additional dialogue? To Shakespeare?

I thought of this during one of “TF3”’s opening credits: “In association with Hasbro.” Hasbro. Creator of Mr. Potato Head and the Easy-Bake Oven. We’re playing with toys here. No, not even. We’re watching others, rich folks, play with toys. We’re paying money to watch rich folks create stories out of 30-year-old toys. We’ve spent nearly $3 billion on this, just in theaters, thus far.

So what’s the plot of this one? Apparently the Prime before Optimus, Sentinel Prime (voice: Leonard Nimoy), in the last days of the Autobot-Decepticon War, attempted to escape with a device that might’ve won the day for the Autobots. But he was shot down, drifted in space for a while, then crashlanded on our moon circa 1958. Just in time for the space race.

Actually, he was the reason for the space race. That’s why JFK, sneaky bastard, gave his “We choose to go to the moon in this decade” speech. We needed to beat the Russians there so Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (sneaky bastards) could explore that alien space ship and get what they could. So we did. So they did.

That’s our history-skewing backdrop. Eventually we get to Sam Witwicky, the everyman protagonist nobody cares about. He’s living in a beautiful well-lit apartment in D.C. with a supermodel girlfriend and a couple of small, comic-relief Autobots, but he’s got nothing but complaints. Three months out of college and he can’t find a job. Carla teases him about this. His comic-relief parents, when they show up, tease him about this. He doesn’t think it’s funny. “I saved the world twice and I can’t even get a job!” he says. He’s got a medal from Pres. Obama (handed to him dismissively), but no one is impressed. It’s all still top secret. Plus he can’t blame his inability to find work on the Great Recession since the “Transformers” movies are all about escapism and the Great Recession is exactly what we’re trying to escape. Might as well have Fred Astaire dance in hobo rags during the Great Depression. (“Easter Parade” was in ’48.)

Here’s a suggestion: Sam might want to temper his job-interview personality. Basically he brings his saving-the-world intensity to the job interview. He puffs up, talks big, offers nothing. It might help, too, if he could remember the name of the job interviewer. But who can blame him, right? It’s a Japanese name and those Japanese names sure are weird and funny.

Mostly, though, Sam just wants to matter again.

Hey, why doesn’t he join the military? Doesn’t he see himself a soldier? Isn’t the film’s most memorable line something Charlotte Mearing (Francis McDormand), Director of National Intelligence, tells him to get rid of him? Doesn’t she say, “You are not a soldier. You are a messenger. You've always been a messenger”? So why not show her, damnit, and become a soldier for real?

Because it would upset the balance of the movie. Everyone is a type here. Mearing’s a bureaucrat (and wrong), the soldiers are soldiers (and move heroically in slow motion), and Witwicky is the intense everyman with the hot, hot girlfriend who gets mixed up in this shit. He can’t go beyond the bounds of his narrow character any more than Optimus Prime can sing like the Pointer Sisters.

Meanwhile, an investigation at Chernobyl turns up a slithery Decepticon named Shockwave (voice: Frank Welker), which leads to the uncovering of the NASA cover-up, and the Chernobyl cover-up (also caused by Transformers), and a demand from Optimus Prime to retrieve both Sentinel Prime and the advanced Autobot technology from the moon.

Except this is all a plot by an injured Megatron (voice: Hugo Weaving), hanging out at the foot of Mt. Kilimanjaro, to regain power. From this we get betrayals human (Dylan Gould) and Autobot (Sentinel Prime). Sentinel Prime then addresses the U.N., demanding that all remaining Autobots (but not Decepticons) leave Earth. Within 24 hours, Congress, cowardly as ever, succumbs to these demands and the Autobots are forced to leave. Their ship is then shot down by the Decepticons, leaving a trail of smoke reminiscent of the Challenger disaster. At which point, the Decepticons take over the world, or at least Chicago, and set up the advanced Autobot technology in order to transport their dead planet, Cybertron, into our solar system. But against all odds, Sam Witwicky and a rag-tag team of mercenaries go in, along with Special Forces, along with, eventually, the Autobots—who were never killed, who faked the launch—and eventually the good guys, who stand for freedom, beat the bad guys, who stand for tyranny, and Sam and Carla run to each other and kiss. It’s up to Optimus Prime to deliver the movie’s last thrilling lines:

In any war, there are calms between the storms. There will be days when we lose faith, days when our allies turn against us. But the day will never come that we forsake this planet and its people.

It’s toys. Sam is the boy playing with his Transformers and G.I. Joes and army men. The buildings are Legos. Carla is his sister’s Barbie. The bureaucrats are whatever: Troll dolls. And Sam makes them all fight and makes the buildings topple. He provides sound effects. Pkschuh! He provides the dialogue. Which explains a lot.

Except it’s not so innocent. There’s a sheen of adult (right-wing?) paranoia and loutishness on top of this childplay.

Question: Who do we trust in these movies? What groups or institutions?

Parents? They’re daft and comic relief.

Government? Bureaucrats are always wrong.

Businessmen? Assholes.

The U.N.? It allows villains to speak there.

Congress? It’s weak, betrays friends, and capitulates on a dime.

Presidents? JFK was a liar and Obama was dismissive.

The Apollo program? It began as a lie and it ended as a lie. Buzz Aldrin even shows up to lie to us some more. Saddest guest appearance ever.

No, it’s just one group we can trust: Soldiers. That’s it. Army men. They’re the only ones. You can even trust them with your hot, model girlfriend and they won’t look at her twice. They’re that trustworthy.

This is a worldview so infantile and paranoid it borders on the psychotic.

“Star Wars” was infantile (good vs. evil, etc.) but it was also expansive. It opened up a universe to Luke Skywalker and us. You found friends everywhere. And the force was with you.

“Transformers” is infantile but shuttered. Everyone you meet is a jerk, an ass, an idiot or in league with your enemies. You trust army men and Optimus Prime and that’s it. Because no one is with you.

And somehow this thing has grossed $3 billion worldwide.

“We were once a peaceful race of intelligent mechanical beings,” Optimus Prime tells us at the beginning of “Transformers 3.” “But then came the war.”

We were once a race of semi-intelligent human beings, I thought at the end of “Transformers 3.” But then ... But then ...

Thursday November 17, 2011

Movie Review: J. Edgar (2011)

WARNING: THE FBI ALWAYS GETS ITS SPOILERS

Biopics are tough. Take a life that has no discernible story arc, create one, and stuff it into two hours of movie time. Fun.

“J. Edgar,” written by Dustin Lance Black and directed by Clint Eastwood, doesn’t do a poor job of it, but it does a familiar job of it. We get the famous figure at the end of his life reflecting on the life. As in “Chaplin,” the intermediary is the biographer, or, in J. Edgar’s case, the biographers. Black also adds a twist at the end but I wish it were more of a twist. I wish it reflected on the entire life, the entire memoir, rather than a small portion of it.

First, let me say I was fascinated by the early stuff: Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s home being bombed by anarchists in 1919 and the “Palmer Raids” in response, and the general fear of Bolsheviks and anarchists along with the deportation not only of foreigners but of U.S. citizens like Emma Goldman (Jessica Hecht). It’s a time period we don’t see much in the movies, yet it felt familiar to me. It’s the same arguments, the same overreactions, we’ve had since 9/11. You get the feeling that what Hoover tells us in voiceover at the end of the movie—“A society unwilling to learn from the past is doomed; we must never forget our history”—is precisely what Clint Eastwood is telling his audience. Learn you history, punks.

In 1919, J. Edgar Hoover (Leonardo DiCaprio) is a prim, proper, legal functionary within the Bureau of Investigation, who, as he survives the various scandals of the Harding-era Justice Department, including the Palmer Raids, rises to power. In 1921, he is appointed deputy head of the Bureau. In 1924, he becomes its acting director. Finally, under Calvin Coolidge, he becomes its director—the sixth in the Bureau’s short history. (It was created in 1908.)

In 1919, J. Edgar Hoover (Leonardo DiCaprio) is a prim, proper, legal functionary within the Bureau of Investigation, who, as he survives the various scandals of the Harding-era Justice Department, including the Palmer Raids, rises to power. In 1921, he is appointed deputy head of the Bureau. In 1924, he becomes its acting director. Finally, under Calvin Coolidge, he becomes its director—the sixth in the Bureau’s short history. (It was created in 1908.)

There’s a good, paranoid sense we get from DiCaprio’s Hoover. He assumes he’ll be bounced from his post at any minute—as easily as he bounces others—and thus scrambles to hold onto power. Should this have been underlined more? This fear of others doing to you what you do to others? The Golden Rule turned on its head? Hoover worried about being fired on a whim because he fired others on a whim. He knew the value of loyalty because he was disloyal. He sought the awful secrets of others because he knew the awful power of his own secrets. He was paranoid and combative because he assumed the world would act as unscrupulously as he did, which is why, in the end, he beat it. Because the world wasn’t as unscrupulous as he was. He had it at an advantage.

And didn’t. He was a closet case, trapped in homophobic times (OK, more homophobic times), without even a sympathetic family to fall back on. When he objects, later in the film, to having to dance with actresses like Ginger Rogers and Anita Colby, his mother (Judi Dench) reminds him of a neighborhood boy, “a daffodil boy,” she calls him, who killed himself after his secret came out. “Edgar,” she says, “I’d rather have a dead son than a daffodil son. Now I’ll teach you to dance.” It’s a sad, effective scene.

Hoover does have a long-time companion, Clyde Tolson (Armie Hammer), a law school graduate who quickly becomes the No. 2 man at the FBI, even though he mostly helps Hoover, a) keep an even keel, and, b) with his clothes. There’s an odd moment at Julius Garfinkel & Co., a D.C. department store. The store’s clerks inform Hoover his credit is no good since someone named John Hoover has been bouncing checks, leaving the Director of the Bureau of Investigation sputtering that he is himself and not someone else. Funny stuff. At which point Clyde vouches for him and a new line of credit is established. Giving up both “John” and “Johnnie,” he signs his name, momentously, J. Edgar Hoover. Ah! The legend being born. Unfortunately, the careful viewer will have noticed, in an earlier scene, a desk nameplate already reading “J. Edgar Hoover.” But Eastwood needs to film his momentous moments.