Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

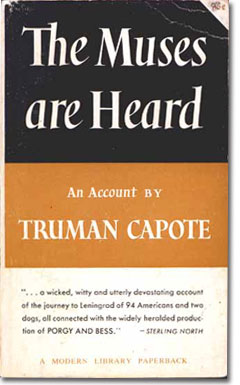

The Muses are Heard

by Truman Capote

Does anyone write this well anymore — for a magazine? Do magazines allow writers this kind of space? This book is so well-written, witty and lengthy that it condemns the present from the past. Our magazines were once capable of this. Now we're not even capable of making sure that this doesn't perish, for the book has been out-of-print for decades. Publishers should hang their heads in shame.

The Muses Are Heard is Truman Capote's ironic, true-life account of following the Everyman Opera Company's journey to the Soviet Union for a production of the Gershwin opera, "Porgy and Bess," during the most frigid part of the Cold War.

Aesthetics are all but lost amid politics and egoes. Directors, journalists, diplomats, stars: Each has high expectations for the journey, and each is involved in machinations to make those expectations a reality. Warner Watson, production assistant, constantly talks about "fencing in" problems. New York Post columnist Leonard Lyons is always anxious to stage "events" during the journey (the cast singing Negro spirituals as they arrive in Leningrad, for example) so he'll have something to write about. At one point he complains that there is in fact "nothing to write about" on this historic journey. The comment comes a third of the way through the book, when it's obvious that someone is finding something to write about.

The most heart-rending moments come during Truman's encounters with Russians who extend a shaky hand toward a morsel of freedom but then retract it for fear of repercussions. There's the pathetic night market in Brest-Litovsk and the sad bar in deepest Leningrad where one old Russian amuses the patrons with his Christ imitation (arms extended, beer spilling out of his empty right eye socket). At another point a young interpreter reaches toward some books Truman has offered him:

At first he was pleased. Then, as he reached for the books, his hand hesitated, withdrew, and his personal tic started; more shrugs, shrinkings, until he was swallowed again in the looseness of his clothes. "I have not the time," he said regretfully.

Great writing throughout. After Truman and Miss Ryan, a curvy assistant, get lost in Leningrad and are rescued by a pied-piper contingent of Russians who lead them back to their hotel, Capote writes, "...we rushed inside, collapsed on a bench and sucked the warm air like divers who had been too long underwater." At the Russian ballet, he writes, "Miss Ryan was wearing a low strapless dress... and as she swayed down the aisle, masculine eyes swerved in her direction like flowers turning toward the sun."

Does Truman overdo it? Many of these characters come off as caricatures. Jackson is a gambling, scheming groom-to-be, while Miss Thigpen, his betrothed, worries about her weight. We get Joe, the Russian, who speaks in outdated American slang ("and all that crap"), and Mrs. Gershwin herself, the queen who pretends she's a citizen.

Is there too much irony? The opening-night reviews from the American press are glowing — for a production Capote found less than spectacular — and Jackson shouts, "We're making history!" to which Warner Watson adds, "I guess we've got history fenced in."

But of course they haven't. It's Truman who fenced in history.

óDecember 24, 1992

© 1999 by Erik Lundegaard