Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

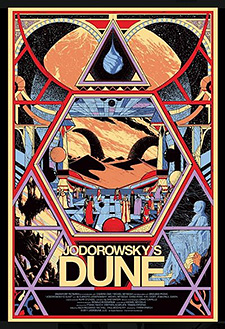

Jodorowsky’s Dune (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

It starred Salvador Dali, Orson Welles, David Carradine, and Mick Jagger, with the director’s 12-year-old son in the starring role. The director, Mexican, had directed the cult avant-garde western “El Topo,” while the producer, French, would produce “Cyrano de Bergerac” and “Burnt by the Sun.” Others on the crew would help make “Alien” and “Total Recall.” The movie itself would influence everything from “Star Wars” to “Raiders of the Lost Ark” to “The Matrix.”

It was Alejandro Jodorowsky’s “Dune” and according to several talking heads in this documentary, it was the greatest movie never made.

It has competition, of course. Would it have been better than Terry Gilliam’s “The Man Who Killed Don Quixote” or Henri-Georges Clouzot’s “L’Enfer”? Or the thousands of really good ideas brought by talented people that not only never got made but never got made into documentaries about movies that never got made? Tough call. We don’t agree on movies that exist; imagine the arguments for this.

Gilliam’s “Don Quixote” died because its star, Jean Rochefort, got sick, and Gilliam refused to compromise with anyone else. Clouzot? He suffered from too much money, too much ambition, and a heart attack after his leading man walked out.

Jodorowsky was certainly ambitious—he wanted to make the greatest movie of all time—but “Dune” died for the opposite reason of Clouzot’s film: Hollywood’s money men weren’t interested.

Not in the subject. In him.

Spiritual warriors

We’re the opposite. We’re fascinated by Jodorowsky because he’s endlessly fascinating. At 84, he’s enthusiastic and boisterous and still has a gleam in his eye about this project. He’s a great storyteller. He’s politically incorrect—joyfully so. He talks about the liberties he took with Frank Herbert’s acclaimed novel by comparing the situation to a husband with a new bride. You can’t respect or idolize her too much. You need to get in there. He mimics tearing open a dress. You need to rape her, he says. He needed to rape Frank Herbert, he says. He says it all with the most joyous smile.

You know those movies where the protagonist assembles a team of professionals to pull off the perfect crime? That’s “Jodorowsky’s Dune.” The doc, directed by Frank Pavich, is about the assembling of a great team.

We get a bit of Jodorowsky’s background. Too little, to be honest. He was an avant-garde theater director in Mexico in the early 1960s but how he got there, and interested in that, we haven’t a clue. But from there he went into film. He directed “Fando and Lis” (1968) which caused near riots at screenings; then “El Topo” (1970), which became the original cult midnight movie; then “The Holy Mountain” (1973). His reputation grew. Producer Michel Seydoux, the grand uncle of Lea, gave him carte blanche. He told him he could make any movie he wanted to make. Jodorowsky said he wanted to make “Dune.” But first he had to read it.

He spent two years assembling his team of “spiritual warriors.” To be on Jodorowsky’s team, you needed more than talent; you needed vision and soul. He wasn’t messing around. Everyone told him he needed Douglas Trumbull, the visual effects guru behind “2001: A Space Odyssey” (and later “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” and “Blade Runner”), but during a meeting Trumbull kept answering his phone and Jodorowsky walked out. Instead he hired French comic-book artist Jean Giraud, a.k.a. Moebius, and British sci-fi cover artist Chris Foss and American artist-writer Dan O’Bannon (“Dark Star,” “Alien,” “Heavy Metal”). He wooed Orson Welles with food, Salvador Dali with wit. Dali recommended a German artist named H.R. Giger, who had never worked in film before.

Serendipity, to hear Jodorowsky tell it, also played a role. He wanted Mick Jagger and suddenly there he was at a party. For the music, he hired Pink Floyd for one planet, X for another. They assembled one of the most extensive storyboards ever into a big book and brought it to Hollywood.

And it didn’t sell.

The studios were interested in most of it; they just weren’t interested in him. They liked the package but not the packager. He was too avant-garde. He was too avant-garde for 1975, which is saying something. So the project died.

Why? I’m curious about that. Did it have to be Hollywood? Couldn’t it have been France? Couldn’t it have been independently financed? No one had $15 million to risk in 1975? And if so, didn’t Jodorowsky and company realize at some point in the process that they needed someone to sell Hollywood on the project? Couldn’t Jodorowsky have found that person, too, the way he found Jagger and Dali and Giger? But of course that person wouldn’t have had the proper spirit. They wouldn’t have been spiritual warriors. Jodorowsky would have dismissed them.

“Dune is a deadly trip,” a character in the movie says. Indeed.

Becoming part of everything

Another question: Would it have been good? Jodorowsky’s version? His vision?

It sounds intriguing. There are elements of a god complex here, and not just in the script. In “El Topo” Jodorowsky plays the title character who says the line, “Soy Dios”: I am God. Here, he talks about the two years he had his son, Brontis, training with a martial arts master to play Paul Atreides. “Why I did that?” he asks now. “Sacrifice my son?” He sacrifices his son in the movie, too. Unlike the novel, Paul dies; but in dying he becomes part of everything. “I am Paul,” the other characters repeat over and over. It’s like a spiritual Spartacus moment. It’s a Jesus moment. It’s Obi wan Kenobi. Being struck down, he becomes more powerful than you can imagine.

Brontis, the son, who must be about my age (51), makes the connection between Paul and the stillborn “Dune.” In dying, in being struck down, it became part of everything. Giger’s work wound up in “Alien,” storyboard shots wound up in “Blade Runner,” the great long opening Jodorowsky envisioned wound up as the great long opening shot of “Contact.” What he envisioned wound up influencing the culture anyway.

Is this a good thing, by the way? Some of the film-critic talking heads in this thing say that if it weren’t for Jodorowsky there wouldn’t have been ... name it. “Blade Runner,” “Masters of the Universe,” “The Matrix.” But would this have been a bad thing? Are those movies really worth our time? Others suggest that if Jodorowsky’s “Dune” had gotten made and released before “Star Wars,” then it, with its more auteuristic vision, would have influenced movies and the culture instead of Lucas’ film. We might not have gone the way of the popcorn blockbuster. Director-driven movies might not have died. Our culture might not have gotten so dumb.

I doubt it. Jodorowsky, for all his influence, never made a popular movie. But we’ll never know for sure.

Ten years later, “Dune” wound up being made anyway, and with the one director Jodorowsky could see making a masterpiece of it: David Lynch. Initially he refused to see it. But his son dragged him to the theater, where he sat, he says, with eyes closed as it began. Gradually, though, he began to watch more of it. And more of it. And he became so happy. Because it was so awful. It was a disaster. It’s an awful feeling, he admits, wanting someone else to fail. But: “It’s a human reaction, no?”

I love him for that, and for the attempt. He’s 84, he tells us from his study, surrounded by his books and memorabilia—including all the trinkets left over from the doomed “Dune” project—but he has the ambition to live to be 300. Why not? “Have the greatest ambition possible,” he tells us. “Do it. ... If you fail, it is not important. You need to try.”

—May 10, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard