Baseball's Active Leaders, 2023

What Trump Said When About COVID

Recent Reviews

Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022)

Black Panther: Wakanda Forever (2022)

Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness (2022)

Spider-Man: No Way Home (2021)

The Cagneys

A Midsummer Night's Dream (1935)

Something to Sing About (1937)

Angels with Dirty Faces (1938)

A Lion Is In the Streets (1953)

Man of a Thousand Faces (1957)

Never Steal Anything Small (1959)

Shake Hands With the Devil (1959)

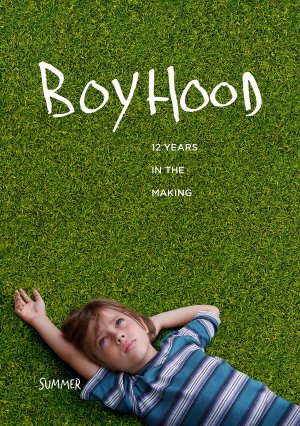

Boyhood (2014)

WARNING: SPOILERS

You know the “Up” series? Michael Apted’s series of documentaries that began with 7-year-olds being interviewed in 1964 and picks up every seven years to see where they are and how they think and what they’ve become? Go deep enough into the series—and they’re at “56 Up” now—and it’s like time-lapse photography of human beings. It’s often profound and moving.

Writer-director Richard Linklater (“Dazed and Confused”) has now done this in the non-documentary form.

| Written by | Richard Linklater |

| Directed by | Richard Linklater |

| Starring | Ellar Coltrane Patricia Arquette Ethan Hawke Lorelai Linklater Elijah Smith |

In 2002, he hired a 6-year-old boy, Ellar Coltrane, and he’s been filming him, in a scripted story, with Patricia Arquette as his mom and Ethan Hawke as his estranged dad, ever since. The story takes us from Mason’s “Aspiration Day” in first grade, in which he sits in the grass staring up at the clouds, to the first day of college, when he’s in the mountains doing basically the same. His hair has darkened, he’s got scruff on his chin, his voice is shockingly deep. You think, as many parents think, “What happened to my little boy?”

Here’s the question going in: Is this more than a stunt? You certainly hope so. You hope “Boyhood” coalesces into something profound and moving and maybe even beautiful.

The arc of the step dad

What surprised me, initially, was how seamlessly it moved. There are no title cards telling us it’s six months or a year later. We infer this from Mason’s haircut or his face or the family’s circumstances.

The circumstances keep changing. In the beginning, he’s living with him mom and his bratty older sister, Samantha (Linklater’s own daughter, Lorelei), with whom he shares bunkbeds. One morning, early in the film, she wakes him up by throwing a pillow at him and then singing Britney Spears’ “Oops! ... I Did It Again” at him. Nothing says “2002” more. It’s her most memorable scene.

Dad? He’s been out of the picture, living in Alaska, but he arrives back in Texas in a souped-up GTO, with a souped-up personality, ready to make up for lost time. He wants to move things fast and make things big, but there’s a desperation in it all that makes him seem small. Initially he seems like a douche but it’s more complicated than that. He’s a grown-up kid, scrounging after rock ‘n’ roll dreams at the end of the rock ‘n’ roll era. It’s not like he’s not talented; we hear a few good songs. And his fatherly advice may sound simplistic (“Life doesn’t give you bumpers,” etc.) but it isn’t wrong. Plus he’s that rare, loudmouthed liberal in conservative Texas railing against the Iraq War in 2004 (and keep in mind: this was in 2004), and putting up Obama lawn signs, and stealing McCain lawn signs, in 2008 (ditto).

Plus he’s Prince Charming compared to the guy Olivia, the mom, winds up with.

She’s taking classes at a nearby university to get a teaching degree when Mason shows up after school and sits in the back row, then witnesses an odd flirtation between her and her professor, Bill Wellbrock (Marco Perella). I got a bad vibe from him immediately, maybe because we’re seeing all of this from Mason’s perspective, which is the perspective of the small and weak, or maybe because Bill has that authoritarian air of a Texas alpha male. Either way, he and Olivia are soon back from a honeymoon in Paris, and Mason and Sam are living with two of Bill’s kids from his first marriage. It’s like “The Brady Bunch” minus one. But not. Bill has a drinking problem. And the authoritarian air slowly becomes totalitarian. He gets on Mason about his chores, then his long hair, then he takes him to the barber and watches, smiling, while the barber shaves it all off. Mason complains to his mom, who says, yes, that wasn’t right, and she’ll talk to Bill. But the next time we see her, Mason’s walking past the half-opened garage and she’s lying on the floor. She tells Mason, a little hysterically, that she just fell, while Bill stands over her making less-than-soothing excuses.

This reveal feels exactly right to me. Even the half-opened garage door. Half the story is hidden, but half isn’t. And from that second half we know what’s going on—even if Mason doesn’t quite. Yet.

Things gets worse at the dinner table when Bill’s drinking goes from surreptitious to in-your-face. Tempers (or a temper) flare, and dishes are thrown. Threats are made. It’s truly scary. It gets scarier when Olivia disappears, but then she returns with a brassy friend for her kids. They get out sloppily, and without Bill’s kids. There’s no justice here, only escape.

Too cool for school?

The arc of the step dad is the one true arc of the movie. Everything else is simply episodic. We keep waiting for other shit to come down, but it doesn’t. Life just happens.

In eighth grade, for example, Mason and his friends hang with two high school boys breaking karate boards and drinking beer on a Friday night. The eighth-graders have their first beers, under pressure, and under pressure tell their first lies about how far they’ve gone with girls. Mason is cool here, but it’s his friend, Tony (Jordan Howard), who delivers the crushing blow to the bullying older kids (including Nick Krause, pre-“Descendants”): If you’re so good with women, what are you doing hanging around with us on a Friday night? We think he’s in for it but he’s not. We think the board-busting will go awry, but it doesn’t. It’s just another night on the journey.

The older Mason gets, the cooler he becomes. Sadly. Little is more boring to me than cool. I want engaged. Is he stoned half the time? Everyone seems intent on waking him up. He gets advice from a photography teacher, a restaurant manager, his mom’s new wrong guy, Jim (Brad Hawkins), and of course mom and dad. Girls try to get his attention. One does. In high school, Sheena (Zoe Graham) becomes the girl, but we don’t really get that until she’s gone, and he’s hurt, but hurt in a way that doesn’t quite register. I’m curious: Does Ellar Coltrane become a less interesting actor the older he gets? Or is teenage solipsism simply less interesting next to childhood enthusiasm? In youth, our eyes are wide; as teenagers, they become half-closed with a worldliness we don’t own yet.

The “Up” series makes you realize how much adolescence fucks us all up. Almost every participant in that documentary is outgoing and bright-eyed at 7, self-conscious and mumbling at 14; then they spend the rest of their lives trying to overcome whatever happened at 13. Mason seems to disappear a bit, too, but less from pain than from a “Whatever” attitude. I remember a much greater awkwardness from 13 to 18. But it could be that Mason (and maybe Coltrane, and maybe Linklater) is cooler than me. It wouldn’t take much.

Are the parental storylines more interesting? For these 12 years, both play catch-up but neither do. She gets pudgier, her temper shorter. He gets thinner and more accepting. He spends less time trying to make something happen and shrugs more often that it never did. He gets a dull, steady job, a second wife, a second batch of kids. He allows himself to become—his word—castrated. In some sense, he’s still a teenager. In most ways, Mason Jr. seems more mature.

Like family

“Boyhood” is set between 2002 and 2014 but I keep coming back to the thought that much of it is culled from Linklater’s own life. So much feels like that odd portion of the 20th century (roughly 1966 to 1978) rather than the first two decades of the 21st. The haircut, for example. That would’ve truly sucked in 1970. But in 2006? Mason would’ve just looked like every other kid. Or Olivia’s helplessness when faced with Bill’s abuse? Again: 1970s. By now, the rules and the laws have changed. Just direct Olivia to a tough female Texas family law attorney and take Bill to the cleaners. Even Mason Sr.’s rock ‘n’ roll dreams seem very 1970s to me.

That said, the movie has moments that feel as real as my own memories: the search for arrowheads, gawking and giggling at lingerie ads, hanging alone in the narrow space between garages. There’s the late-night, teenage drop-off in the station wagon after drinking, and the makeout sessions in same. The friends that come and go.

That said, the teenage years seem prolonged to me. Intentionally? In “The Hotel New Hampshire,” John Irving wrote how we seem 15 forever, then suddenly we’re in our 20s and 30s and time just zips, and he structured his novel that way—so that the teenage years simply take up more pages of the book. Maybe Linklater is doing something similar? Or did he simply edit the earlier scenes to a smooth finish while the more recent years were allowed their unnecessary material? Because it does feel like unnecessary material. The movie takes too long to end—as if Linklater didn’t want it to. Yes, “Boyhood” is often profound and moving and even beautiful, but I didn’t leave the theater the way I wanted to: stunned. A high bar, I know. The highest.

But something else happens in the days after seeing the film, something unique in my moviegoing experience for this truly unique film. Because we watch this young actor for 12 years of his life, and see him grow from blonde boy to too-cool-for-school adolescent, this fact alone affects us on a deep level. There’s a pang when we think of him and the boy he once was. It’s almost as if he’s family.

—June 14, 2014

© 2014 Erik Lundegaard